PREGABALIN by Cardinal Health 107, LLC / Aphena Pharma Solutions - Tennessee, LLC PREGABALIN capsule

PREGABALIN by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

PREGABALIN by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Cardinal Health 107, LLC, Aphena Pharma Solutions - Tennessee, LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use PREGABALIN CAPSULES safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for PREGABALIN CAPSULES.

PREGABALIN capsules, for oral use, CV

Initial U.S. Approval: 2004INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Pregabalin capsules are indicated for:

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

- For adult indications, begin dosing at 150 mg/day. For partial-onset seizure dosing in pediatric patients 1 month of age and older, refer to section 2.4. (2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6)

- Dosing recommendations:

INDICATION

Dosing Regimen

Maximum Dose

DPN Pain (2.2)

3 divided doses per

day300 mg/day within 1 week

PHN (2.3)2 or 3 divided doses

per day300 mg/day within 1 week.

Maximum dose of 600 mg/day.Adjunctive Therapy

for Partial-Onset

Seizures in Pediatric

and Adult Patients

Weighing 30 kg or

More (2.4)2 or 3 divided doses

per dayMaximum dose of 600 mg/day.

Adjunctive Therapy

for Partial-Onset

Seizures in Pediatric

Patients Weighing

Less than 30 kg

(2.4)1 month to less than

4 years:

3 divided doses

per day

4 years and older:

2 or 3 divided

doses per day14 mg/kg/day.

Fibromyalgia (2.5)

2 divided doses per

day300 mg/day within 1 week.

Maximum dose of 450 mg/day.Neuropathic Pain

Associated with

Spinal Cord Injury

(2.6)2 divided doses per

day300 mg/day within 1 week.

Maximum dose of 600 mg/day.- Dose should be adjusted in adult patients with reduced renal function. (2.7)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- Capsules: 25 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg, 225 mg, and 300 mg. (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Known hypersensitivity to pregabalin or any of its components. (4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Angioedema (e.g., swelling of the throat, head, and neck) can occur, and may be associated with life-threatening respiratory compromise requiring emergency treatment. Discontinue pregabalin immediately in these cases. (5.1)

- Hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., hives, dyspnea, and wheezing) can occur. Discontinue pregabalin immediately in these patients. (5.2)

- Antiepileptic drugs, including pregabalin, the active ingredient in pregabalin capsules, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior. (5.3)

- Abrupt or rapid discontinuation may increase the risk for seizures. Withdrawal symptoms or suicidal behavior and ideation have been observed after discontinuation. Taper pregabalin gradually over a minimum of 1 week. (5.4)

- Respiratory depression: May occur with pregabalin, when used with concomitant CNS depressants or in the setting of underlying respiratory impairment. Monitor patients and adjust dosage as appropriate. (5.5)

- Pregabalin may cause dizziness and somnolence and impair patients’ ability to drive or operate machinery. (5.6)

- Pregabalin may cause peripheral edema. Exercise caution when co-administering pregabalin and thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agents.(5.7)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most common adverse reactions (greater than or equal to 5% and twice placebo) in adults are dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, edema, blurred vision, weight gain, and thinking abnormal (primarily difficulty with concentration/attention). (6.1)

Most common adverse reactions (greater than or equal to 5% and twice placebo) in pediatric patients for the treatment of partial-onset seizures are increased weight and increased appetite. (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Rising Pharma Holdings, Inc. at 1-844-874-7464 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 9/2025

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Important Administration Instructions

2.2 Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Adults

2.3 Postherpetic Neuralgia in Adults

2.4 Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 1 Month of Age and Older

2.5 Management of Fibromyalgia in Adults

2.6 Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord Injury in Adults

2.7 Dosing for Adult Patients with Renal Impairment

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Angioedema

5.2 Hypersensitivity

5.3 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

5.4 Increased Risk of Adverse Reactions with Abrupt or Rapid Discontinuation

5.5 Respiratory Depression

5.6 Dizziness and Somnolence

5.7 Peripheral Edema

5.8 Weight Gain

5.9 Tumorigenic Potential

5.10 Ophthalmological Effects

5.11 Creatine Kinase Elevations

5.12 Decreased Platelet Count

5.13 PR Interval Prolongation

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Renal Impairment

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

14.2 Postherpetic Neuralgia

14.3 Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 1 Month of Age and Older

14.4 Management of Fibromyalgia

14.5 Management of Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord Injury

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Pregabalin capsules are indicated for:

- Management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy

- Management of postherpetic neuralgia

- Adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in patients 1 month of age and older

- Management of fibromyalgia

- Management of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Important Administration Instructions

Pregabalin capsules are given orally with or without food.

When discontinuing pregabalin capsules, taper gradually over a minimum of 1 week [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Because pregabalin is eliminated primarily by renal excretion, adjust the dose in adult patients with reduced renal function [see Dosage and Administration (2.7)].2.2 Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Adults

The maximum recommended dose of pregabalin capsules is 100 mg three times a day (300 mg/day) in patients with creatinine clearance of at least 60 mL/min. Begin dosing at 50 mg three times a day (150 mg/day). The dose may be increased to 300 mg/day within 1 week based on efficacy and tolerability.

Although pregabalin was also studied at 600 mg/day, there is no evidence that this dose confers additional significant benefit and this dose was less well tolerated. In view of the dose-dependent adverse reactions, treatment with doses above 300 mg/day is not recommended [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

2.3 Postherpetic Neuralgia in Adults

The recommended dose of pregabalin capsules is 75 to 150 mg two times a day, or 50 to 100 mg three times a day (150 to 300 mg/day) in patients with creatinine clearance of at least 60 mL/min. Begin dosing at 75 mg two times a day, or 50 mg three times a day (150 mg/day). The dose may be increased to 300 mg/day within 1 week based on efficacy and tolerability.

Patients who do not experience sufficient pain relief following 2 to 4 weeks of treatment with 300 mg/day, and who are able to tolerate pregabalin, may be treated with up to 300 mg two times a day, or 200 mg three times a day (600 mg/day). In view of the dose-dependent adverse reactions and the higher rate of treatment discontinuation due to adverse reactions, reserve dosing above 300 mg/day for those patients who have on-going pain and are tolerating 300 mg daily [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

2.4 Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 1 Month of Age and Older

The recommended dosages for adults and pediatric patients 1 month of age and older are included in Table 1. Administer the total daily dosage orally in two or three divided doses as indicated in Table 1. In pediatric patients, the recommended dosing regimen is dependent upon body weight. Based on clinical response and tolerability, dosage may be increased, approximately weekly.

Table 1. Recommended Dosage for Adults and Pediatric Patients 1 Month and Older

Age and Body Weight

Recommended Initial Dosage

Recommended Maximum Dosage

Frequency of Administration

Adults (17 years and older)

150 mg/day

600 mg/day

2 or 3 divided dosesPediatric patients weighing 30 kg or more

2.5 mg/kg/day

10 mg/kg/day (not to exceed 600 mg/day)

2 or 3 divided dosesPediatric patients weighing less than 30 kg

3.5 mg/kg/day

14 mg/kg/day

1 month to less than 4 years of age:

3 divided doses

4 years of age and older:

2 or 3 divided dosesBoth the efficacy and adverse event profiles of pregabalin have been shown to be dose-related.

The effect of dose escalation rate on the tolerability of pregabalin has not been formally studied.

The efficacy of adjunctive pregabalin in patients taking gabapentin has not been evaluated in controlled trials. Consequently, dosing recommendations for the use of pregabalin with gabapentin cannot be offered.2.5 Management of Fibromyalgia in Adults

The recommended dose of pregabalin capsules for fibromyalgia is 300 to 450 mg/day. Begin dosing at 75 mg two times a day (150 mg/day). The dose may be increased to 150 mg two times a day (300 mg/day) within 1 week based on efficacy and tolerability. Patients who do not experience sufficient benefit with 300 mg/day may be further increased to 225 mg two times a day (450 mg/day). Although pregabalin was also studied at 600 mg/day, there is no evidence that this dose confers additional benefit and this dose was less well tolerated. In view of the dose-dependent adverse reactions, treatment with doses above 450 mg/day is not recommended [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

2.6 Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord Injury in Adults

The recommended dose range of pregabalin capsules for the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury is 150 to 600 mg/day. The recommended starting dose is 75 mg two times a day (150 mg/day). The dose may be increased to 150 mg two times a day (300 mg/day) within 1 week based on efficacy and tolerability. Patients who do not experience sufficient pain relief after 2 to 3 weeks of treatment with 150 mg two times a day and who tolerate pregabalin may be treated with up to 300 mg two times a day [see Clinical Studies (14.5)].

2.7 Dosing for Adult Patients with Renal Impairment

In view of dose-dependent adverse reactions and since pregabalin is eliminated primarily by renal excretion, adjust the dose in adult patients with reduced renal function. The use of pregabalin capsules in pediatric patients with compromised renal function has not been studied.

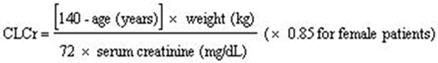

Base the dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment on creatinine clearance (CLcr), as indicated in Table 2. To use this dosing table, an estimate of the patient's CLcr in mL/min is needed. CLcr in mL/min may be estimated from serum creatinine (mg/dL) determination using the Cockcroft and Gault equation:Next, refer to the Dosage and Administration section to determine the recommended total daily dose based on indication, for a patient with normal renal function (CLcr greater than or equal to 60 mL/min). Then refer to Table 2 to determine the corresponding renal adjusted dose.

(For example: A patient initiating pregabalin therapy for postherpetic neuralgia with normal renal function (CLcr greater than or equal to 60 mL/min), receives a total daily dose of 150 mg/day pregabalin. Therefore, a renal impaired patient with a CLcr of 50 mL/min would receive a total daily dose of 75 mg/day pregabalin administered in two or three divided doses.)

For patients undergoing hemodialysis, adjust the pregabalin daily dose based on renal function. In addition to the daily dose adjustment, administer a supplemental dose immediately following every 4-hour hemodialysis treatment (see Table 2).

Table 2. Pregabalin Dosage Adjustment Based on Renal Function

Creatinine Clearance (CLcr)

(mL/min)

Total Pregabalin Daily Dose

(mg/day)*

Dose Regimen

Greater than or equal to 60

150

300

450

600

BID or TID

30 to 60

75

150

225

300

BID or TID

15 to 30

25 to 50

75

100 to 150

150

QD or BID

Less than 15

25

25 to 50

50 to 75

75

QD

Supplementary dosage following hemodialysis (mg)†

Patients on the 25 mg QD regimen: take one supplemental dose of 25 mg or 50 mg

Patients on the 25 to 50 mg QD regimen: take one supplemental dose of 50 mg or 75 mg

Patients on the 50 to 75 mg QD regimen: take one supplemental dose of 75 mg or 100 mg

Patients on the 75 mg QD regimen: take one supplemental dose of 100 mg or 150 mgTID = Three divided doses; BID = Two divided doses; QD = Single daily dose.

* Total daily dose (mg/day) should be divided as indicated by dose regimen to provide mg/dose.

† Supplementary dose is a single additional dose. -

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Capsules: 25 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg, 225 mg, and 300 mg

[see Description (11) and How Supplied/Storage and Handling (16)]

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

Pregabalin capsules are contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to pregabalin or any of its components. Angioedema and hypersensitivity reactions have occurred in patients receiving pregabalin therapy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Angioedema

There have been postmarketing reports of angioedema in patients during initial and chronic treatment with pregabalin. Specific symptoms included swelling of the face, mouth (tongue, lips, and gums), and neck (throat and larynx). There were reports of life-threatening angioedema with respiratory compromise requiring emergency treatment. Discontinue pregabalin immediately in patients with these symptoms.

Exercise caution when prescribing pregabalin to patients who have had a previous episode of angioedema. In addition, patients who are taking other drugs associated with angioedema (e.g., angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [ACE-inhibitors]) may be at increased risk of developing angioedema.

5.2 Hypersensitivity

There have been postmarketing reports of hypersensitivity in patients shortly after initiation of treatment with pregabalin. Adverse reactions included skin redness, blisters, hives, rash, dyspnea, and wheezing. Discontinue pregabalin immediately in patients with these symptoms.

5.3 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including pregabalin, the active ingredient in pregabalin, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Suicidal behavior and ideation have also been reported in patients after discontinuation of pregabalin [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]. Monitor patients treated with any AED for any indication for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI:1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5 to 100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed.

Table 3 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 1. Risk by Indication for Antiepileptic Drugs in the Pooled Analysis Indication Placebo Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients Relative Risk:

Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo PatientsRisk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients

Epilepsy

Psychiatric

Other

Total

1.0

5.7

1.0

2.4

3.4

8.5

1.8

4.3

3.5

1.5

1.9

1.8

2.4

2.9

0.9

1.9The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing pregabalin or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.5.4 Increased Risk of Adverse Reactions with Abrupt or Rapid Discontinuation

As with all antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), withdraw pregabalin gradually to minimize the potential of increased seizure frequency in patients with seizure disorders.

Following abrupt or rapid discontinuation of pregabalin, some patients reported symptoms including insomnia, nausea, headache, anxiety, hyperhidrosis, and diarrhea [see Adverse Reactions (6.2), Drug Abuse and Dependence (9.3)]. Suicidal behavior and ideation have also been reported in patients after discontinuation of pregabalin [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

If pregabalin is discontinued, taper the drug gradually over a minimum of 1 week rather than discontinue the drug abruptly.

5.5 Respiratory Depression

There is evidence from case reports, human studies, and animal studies associating pregabalin with serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression when co-administered with central nervous system (CNS) depressants, including opioids, or in the setting of underlying respiratory impairment. When the decision is made to co-prescribe pregabalin with another CNS depressant, particularly an opioid, or to prescribe pregabalin to patients with underlying respiratory impairment, monitor patients for symptoms of respiratory depression and sedation, and consider initiating pregabalin at a low dose. The management of respiratory depression may include close observation, supportive measures, and reduction or withdrawal of CNS depressants (including pregabalin).

There is more limited evidence from case reports, animal studies, and human studies associating pregabalin with serious respiratory depression, without co-administered CNS depressants or without underlying respiratory impairment.

5.6 Dizziness and Somnolence

Pregabalin may cause dizziness and somnolence. Inform patients that pregabalin-related dizziness and somnolence may impair their ability to perform tasks such as driving or operating machinery [see Patient Counseling Information (17)].

In the pregabalin controlled trials in adult patients, dizziness was experienced by 30% of pregabalin-treated patients compared to 8% of placebo-treated patients; somnolence was experienced by 23% of pregabalin-treated patients compared to 8% of placebo-treated patients. Dizziness and somnolence generally began shortly after the initiation of pregabalin therapy and occurred more frequently at higher doses. Dizziness and somnolence were the adverse reactions most frequently leading to withdrawal (4% each) from controlled studies. In pregabalin-treated patients reporting these adverse reactions in short-term, controlled studies, dizziness persisted until the last dose in 30% and somnolence persisted until the last dose in 42% of patients [see Drug Interactions (7)].

In the pregabalin controlled trials in pediatric patients 4 to less than 17 years of age and 1 month to less than 4 years of age for the treatment of partial-onset seizures, somnolence was reported in 21% and 15% of pregabalin-treated patients compared to 14% and 9% of placebo-treated patients, respectively, and occurred more frequently at higher doses. For patients 1 month to less than 4 years of age, somnolence includes related terms lethargy, sluggishness, and hypersomnia.

5.7 Peripheral Edema

Pregabalin treatment may cause peripheral edema. In short-term trials of patients without clinically significant heart or peripheral vascular disease, there was no apparent association between peripheral edema and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension or congestive heart failure. Peripheral edema was not associated with laboratory changes suggestive of deterioration in renal or hepatic function.

In controlled clinical trials in adult patients, the incidence of peripheral edema was 6% in the pregabalin group compared with 2% in the placebo group. In controlled clinical trials, 0.5% of pregabalin patients and 0.2% placebo patients withdrew due to peripheral edema.

Higher frequencies of weight gain and peripheral edema were observed in patients taking both pregabalin and a thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agent compared to patients taking either drug alone. The majority of patients using thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agents in the overall safety database were participants in studies of pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. In this population, peripheral edema was reported in 3% (2/60) of patients who were using thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agents only, 8% (69/859) of patients who were treated with pregabalin only, and 19% (23/120) of patients who were on both pregabalin and thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agents. Similarly, weight gain was reported in 0% (0/60) of patients on thiazolidinediones only; 4% (35/859) of patients on pregabalin only; and 7.5% (9/120) of patients on both drugs.

As the thiazolidinedione class of antidiabetic drugs can cause weight gain and/or fluid retention, possibly exacerbating or leading to heart failure, exercise caution when co-administering pregabalin and these agents.

Because there are limited data on congestive heart failure patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III or IV cardiac status, exercise caution when using pregabalin in these patients.

5.8 Weight Gain

Pregabalin treatment may cause weight gain. In pregabalin controlled clinical trials in adult patients of up to 14 weeks, a gain of 7% or more over baseline weight was observed in 9% of pregabalin-treated patients and 2% of placebo-treated patients. Few patients treated with pregabalin (0.3%) withdrew from controlled trials due to weight gain. Pregabalin associated weight gain was related to dose and duration of exposure but did not appear to be associated with baseline BMI, gender, or age. Weight gain was not limited to patients with edema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

Although weight gain was not associated with clinically important changes in blood pressure in short-term controlled studies, the long-term cardiovascular effects of pregabalin-associated weight gain are unknown.

Among diabetic patients, pregabalin-treated patients gained an average of 1.6 kg (range: -16 to 16 kg), compared to an average 0.3 kg (range: -10 to 9 kg) weight gain in placebo patients. In a cohort of 333 diabetic patients who received pregabalin for at least 2 years, the average weight gain was 5.2 kg.

While the effects of pregabalin-associated weight gain on glycemic control have not been systematically assessed, in controlled and longer-term open label clinical trials with diabetic patients, pregabalin treatment did not appear to be associated with loss of glycemic control (as measured by HbA1C).

5.9 Tumorigenic Potential

In standard preclinical in vivo lifetime carcinogenicity studies of pregabalin, an unexpectedly high incidence of hemangiosarcoma was identified in two different strains of mice [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)]. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown. Clinical experience during pregabalin's premarketing development provides no direct means to assess its potential for inducing tumors in humans.

In clinical studies across various patient populations, comprising 6,396 patient-years of exposure in patients greater than 12 years of age, new or worsening-preexisting tumors were reported in 57 patients. Without knowledge of the background incidence and recurrence in similar populations not treated with pregabalin, it is impossible to know whether the incidence seen in these cohorts is or is not affected by treatment.

5.10 Ophthalmological Effects

In controlled studies in adult patients, a higher proportion of patients treated with pregabalin reported blurred vision (7%) than did patients treated with placebo (2%), which resolved in a majority of cases with continued dosing. Less than 1% of patients discontinued pregabalin treatment due to vision-related events (primarily blurred vision).

Prospectively planned ophthalmologic testing, including visual acuity testing, formal visual field testing and dilated funduscopic examination, was performed in over 3,600 patients. In these patients, visual acuity was reduced in 7% of patients treated with pregabalin, and 5% of placebo-treated patients. Visual field changes were detected in 13% of pregabalin-treated, and 12% of placebo-treated patients. Funduscopic changes were observed in 2% of pregabalin-treated and 2% of placebo-treated patients.

Although the clinical significance of the ophthalmologic findings is unknown, inform patients to notify their physician if changes in vision occur. If visual disturbance persists, consider further assessment. Consider more frequent assessment for patients who are already routinely monitored for ocular conditions [see Patient Counseling Information (17)].

5.11 Creatine Kinase Elevations

Pregabalin treatment was associated with creatine kinase elevations. Mean changes in creatine kinase from baseline to the maximum value were 60 U/L for pregabalin-treated patients and 28 U/L for the placebo patients. In all controlled trials in adult patients across multiple patient populations, 1.5% of patients on pregabalin and 0.7% of placebo patients had a value of creatine kinase at least three times the upper limit of normal. Three pregabalin-treated subjects had events reported as rhabdomyolysis in premarketing clinical trials. The relationship between these myopathy events and pregabalin is not completely understood because the cases had documented factors that may have caused or contributed to these events. Instruct patients to promptly report unexplained muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness, particularly if these muscle symptoms are accompanied by malaise or fever. Discontinue treatment with pregabalin if myopathy is diagnosed or suspected or if markedly elevated creatine kinase levels occur.

5.12 Decreased Platelet Count

Pregabalin treatment was associated with a decrease in platelet count. Pregabalin-treated subjects experienced a mean maximal decrease in platelet count of 20 × 103/µL, compared to 11 × 103/µL in placebo patients. In the overall database of controlled trials in adult patients, 2% of placebo patients and 3% of pregabalin patients experienced a potentially clinically significant decrease in platelets, defined as 20% below baseline value and less than 150 × 103/µL. A single pregabalin-treated subject developed severe thrombocytopenia with a platelet count less than 20 × 103/ µL. In randomized controlled trials, pregabalin was not associated with an increase in bleeding-related adverse reactions.

5.13 PR Interval Prolongation

Pregabalin treatment was associated with PR interval prolongation. In analyses of clinical trial ECG data in adult patients, the mean PR interval increase was 3 to 6 msec at pregabalin doses greater than or equal to 300 mg/day. This mean change difference was not associated with an increased risk of PR increase greater than or equal to 25% from baseline, an increased percentage of subjects with on-treatment PR greater than 200 msec, or an increased risk of adverse reactions of second or third degree AV block.

Subgroup analyses did not identify an increased risk of PR prolongation in patients with baseline PR prolongation or in patients taking other PR prolonging medications. However, these analyses cannot be considered definitive because of the limited number of patients in these categories.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are described elsewhere in the labeling:

- Angioedema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Hypersensitivity [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Suicidal Behavior and Ideation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Increased Risk of Adverse Reactions with Abrupt or Rapid Discontinuation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Respiratory Depression [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Dizziness and Somnolence [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Peripheral Edema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Weight Gain [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Tumorigenic Potential [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

- Ophthalmological Effects [see Warnings and Precautions (5.10)]

- Creatine Kinase Elevations [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]

- Decreased Platelet Count [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)]

- PR Interval Prolongation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

In all controlled and uncontrolled trials across various patient populations during the premarketing development of pregabalin, more than 10,000 patients have received pregabalin. Approximately 5,000 patients were treated for 6 months or more, over 3,100 patients were treated for 1 year or longer, and over 1,400 patients were treated for at least 2 years.

Adverse Reactions Most Commonly Leading to Discontinuation in All Premarketing Controlled Clinical Studies

In premarketing controlled trials of all adult populations combined, 14% of patients treated with pregabalin and 7% of patients treated with placebo discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the adverse reactions most frequently leading to discontinuation were dizziness (4%) and somnolence (4%). In the placebo group, 1% of patients withdrew due to dizziness and less than 1% withdrew due to somnolence. Other adverse reactions that led to discontinuation from controlled trials more frequently in the pregabalin group compared to the placebo group were ataxia, confusion, asthenia, thinking abnormal, blurred vision, incoordination, and peripheral edema (1% each).

Most Common Adverse Reactions in All Controlled Clinical Studies in Adults

In premarketing controlled trials of all adult patient populations combined (including DPN, PHN, and adult patients with partial-onset seizures), dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, edema, blurred vision, weight gain, and "thinking abnormal" (primarily difficulty with concentration/attention) were more commonly reported by subjects treated with pregabalin than by subjects treated with placebo (greater than or equal to 5% and twice the rate of that seen in placebo).

Controlled Studies with Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

In clinical trials in adults with neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, 9% of patients treated with pregabalin and 4% of patients treated with placebo discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the most common reasons for discontinuation due to adverse reactions were dizziness (3%) and somnolence (2%). In comparison, less than 1% of placebo patients withdrew due to dizziness and somnolence. Other reasons for discontinuation from the trials, occurring with greater frequency in the pregabalin group than in the placebo group, were asthenia, confusion, and peripheral edema. Each of these events led to withdrawal in approximately 1% of patients.

Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 4 lists all adverse reactions, regardless of causality, occurring in greater than or equal to 1% of patients with neuropathic pain associated with diabetic neuropathy in the combined pregabalin group for which the incidence was greater in this combined pregabalin group than in the placebo group. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in clinical studies had adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of "mild" or "moderate".

Table 4. Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Trials in Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

Body system Preferred term

75 mg/day [N=77]

%

150 mg/day [N=212]

%

300 mg/day [N=321]

%

600 mg/day [N=369]

%

All PGB*

[N=979]

%

Placebo

[N=459]

%

Body as a whole

Asthenia

4

2

4

7

5

2

Accidental injury

5

2

2

6

4

3

Back pain

0

2

1

2

2

0

Chest pain

4

1

1

2

2

1

Face edema

0

1

1

2

1

0

Digestive system

Dry mouth

3

2

5

7

5

1

Constipation

0

2

4

6

4

2

Flatulence

3

0

2

3

2

1

Metabolic and nutritional disorders

Peripheral edema

4

6

9

12

9

2

Weight gain

0

4

4

6

4

0

Edema

0

2

4

2

2

0

Hypoglycemia

1

3

2

1

2

1

Nervous system

Dizziness

8

9

23

29

21

5

Somnolence

4

6

13

16

12

3

Neuropathy

9

2

2

5

4

3

Ataxia

6

1

2

4

3

1

Vertigo

1

2

2

4

3

1

Confusion

0

1

2

3

2

1

Euphoria

0

0

3

2

2

0

Incoordination

1

0

2

2

2

0

Thinking abnormal†

1

0

1

3

2

0

Tremor

1

1

1

2

1

0

Abnormal gait

1

0

1

3

1

0

Amnesia

3

1

0

2

1

0

Nervousness

0

1

1

1

1

0

Respiratory system

Dyspnea

3

0

2

2

2

1

Special senses

Blurry vision‡

3

1

3

6

4

2

Abnormal vision

1

0

1

1

1

0* PGB: pregabalin

† Thinking abnormal primarily consists of events related to difficulty with concentration/attention but also includes events related to cognition and language problems and slowed thinking.

‡ Investigator term; summary level term is amblyopiaControlled Studies in Postherpetic Neuralgia

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

In clinical trials in adults with postherpetic neuralgia, 14% of patients treated with pregabalin and 7% of patients treated with placebo discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the most common reasons for discontinuation due to adverse reactions were dizziness (4%) and somnolence (3%). In comparison, less than 1% of placebo patients withdrew due to dizziness and somnolence. Other reasons for discontinuation from the trials, occurring in greater frequency in the pregabalin group than in the placebo group, were confusion (2%), as well as peripheral edema, asthenia, ataxia, and abnormal gait (1% each).

Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 5 lists all adverse reactions, regardless of causality, occurring in greater than or equal to 1% of patients with neuropathic pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia in the combined pregabalin group for which the incidence was greater in this combined pregabalin group than in the placebo group. In addition, an event is included, even if the incidence in the all pregabalin group is not greater than in the placebo group, if the incidence of the event in the 600 mg/day group is more than twice that in the placebo group. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in clinical studies had adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of “mild” or “moderate”. Overall, 12.4% of all pregabalin-treated patients and 9.0% of all placebo-treated patients had at least one severe event while 8% of pregabalin-treated patients and 4.3% of placebo-treated patients had at least one severe treatment-related adverse event.

Table 5. Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Trials in Neuropathic Pain Associated with Postherpetic Neuralgia

Body system Preferred term

75 mg/d [N=84]

%

150 mg/d [N=302]

%

300 mg/d [N=312]

%

600 mg/d [N=154]

%

All PGB* [N=852]

%

Placebo [N=398]

%

Body as a whole

Infection

14

8

6

3

7

4

Headache

5

9

5

8

7

5

Pain

5

4

5

5

5

4

Accidental injury

4

3

3

5

3

2

Flu syndrome

1

2

2

1

2

1

Face edema

0

2

1

3

2

1

Digestive system

Dry mouth

7

7

6

15

8

3

Constipation

4

5

5

5

5

2

Flatulence

2

1

2

3

2

1

Vomiting

1

1

3

3

2

1

Metabolic and nutritional disorders

Peripheral edema

0

8

16

16

12

4

Weight gain

1

2

5

7

4

0

Edema

0

1

2

6

2

1

Musculoskeletal system

Myasthenia

1

1

1

1

1

0

Nervous system

Dizziness

11

18

31

37

26

9

Somnolence

8

12

18

25

16

5

Ataxia

1

2

5

9

5

1

Abnormal gait

0

2

4

8

4

1

Confusion

1

2

3

7

3

0

Thinking abnormal†

0

2

1

6

2

2

Incoordination

2

2

1

3

2

0

Amnesia

0

1

1

4

2

0

Speech disorder

0

0

1

3

1

0

Respiratory system

Bronchitis

0

1

1

3

1

1

Special senses

Blurry vision‡

1

5

5

9

5

3

Diplopia

0

2

2

4

2

0

Abnormal vision

0

1

2

5

2

0

Eye Disorder

0

1

1

2

1

0

Urogenital System

Urinary Incontinence

0

1

1

2

1

0* PGB: pregabalin

† Thinking abnormal primarily consists of events related to difficulty with concentration/attention but also includes events related to cognition and language problems and slowed thinking.

‡ Investigator term; summary level term is amblyopia

Controlled Studies of Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Adult Patients

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

Approximately 15% of patients receiving pregabalin and 6% of patients receiving placebo in trials of adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the adverse reactions most frequently leading to discontinuation were dizziness (6%), ataxia (4%), and somnolence (3%). In comparison, less than 1% of patients in the placebo group withdrew due to each of these events. Other adverse reactions that led to discontinuation of at least 1% of patients in the pregabalin group and at least twice as frequently compared to the placebo group were asthenia, diplopia, blurred vision, thinking abnormal, nausea, tremor, vertigo, headache, and confusion (which each led to withdrawal in 2% or less of patients).Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 6 lists all dose-related adverse reactions occurring in at least 2% of all pregabalin-treated patients. Dose-relatedness was defined as the incidence of the adverse event in the 600 mg/day group was at least 2% greater than the rate in both the placebo and 150 mg/day groups. In these studies, 758 patients received pregabalin and 294 patients received placebo for up to 12 weeks. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in clinical studies had adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of "mild" or "moderate".

Table 6. Dose-related Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Trials of Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Adult Patients

Body System Preferred Term

150 mg/d

[N = 185]

%

300 mg/d

[N = 90]

%

600 mg/d

[N = 395]

%

All PGB*

[N = 670]†

%

Placebo

[N = 294]

%

Body as a Whole

Accidental Injury

7

11

10

9

5

Pain

3

2

5

4

3

Digestive System

Increased Appetite

2

3

6

5

1

Dry Mouth

1

2

6

4

1

Constipation

1

1

7

4

2

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders

Weight Gain

5

7

16

12

1

Peripheral Edema

3

3

6

5

2

Nervous System

Dizziness

18

31

38

32

11

Somnolence

11

18

28

22

11

Ataxia

6

10

20

15

4

Tremor

3

7

11

8

4

Thinking Abnormal‡

4

8

9

8

2

Amnesia

3

2

6

5

2

Speech Disorder

1

2

7

5

1

Incoordination

1

3

6

4

1

Abnormal Gait

1

3

5

4

0

Twitching

0

4

5

4

1

Confusion

1

2

5

4

2

Myoclonus

1

0

4

2

0

Special Senses

Blurred Vision§

5

8

12

10

4

Diplopia

5

7

12

9

4

Abnormal Vision

3

1

5

4

1* PGB: pregabalin

† Excludes patients who received the 50 mg dose in Study E1.

‡ Thinking abnormal primarily consists of events related to difficulty with concentration/attention but also includes events related to cognition and language problems and slowed thinking.

§ Investigator term; summary level term is amblyopia.Controlled Study of Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 4 to Less Than 17 Years of Age

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

Approximately 2.5% of patients receiving pregabalin and no patients receiving placebo in trials of adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence (3 patients), worsening of epilepsy (1 patient), and hallucination (1 patient).

Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 7 lists all dose-related adverse reactions occurring in at least 2% of all pregabalin-treated patients. Dose-relatedness was defined as an incidence of the adverse event in the 10 mg/kg/day group that was at least 2% greater than the rate in both the placebo and 2.5 mg/kg/day groups. In this study, 201 patients received pregabalin and 94 patients received placebo for up to 12 weeks. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in the clinical study had adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of "mild" or "moderate”.

Table 7. Dose-related Adverse Reaction Incidence in a Controlled Trial in Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 4 to Less Than 17 Years of AgeBody System Preferred Term

2.5 mg/kg/daya

[N=104]

%

10 mg/kg/dayb

[N=97]

%All PGB

[N=201]

%

Placebo

[N=94]

%Gastrointestinal disorders

Salivary hypersecretion

1

4

2

0Investigations

Weight increased

4

13

8

4Metabolism and nutrition disorders

Increased appetite

7

10

8

4Nervous system disorders

Somnolence

17

26

21

14Abbreviations: N=number of patients; PGB = pregabalin.

a. 2.5 mg/kg/day: Maximum dose 150 mg/day. Includes patients less than 30 kg for whom dose was adjusted to 3.5 mg/kg/day.

b. 10 mg/kg/day: Maximum dose 600 mg/day. Includes patients less than 30 kg for whom dose was adjusted to 14 mg/kg/day.

Controlled Study of Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 1 Month to Less Than 4 Years of Age

Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 8 lists all dose-related adverse reactions occurring in at least 2% of all pregabalin-treated patients. Dose-relatedness was defined as an incidence of the adverse event in the 14 mg/kg/day group that was at least 2% greater than the rate in both the placebo and 7 mg/kg/day groups. In this study, 105 patients received pregabalin and 70 patients received placebo for up to 14 days.

Table 8. Dose-related Adverse Reaction Incidence in a Controlled Trial in Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures in Patients 1 Month to Less Than 4 Years of AgeBody System Preferred Term

7 mg/kg/day

[N=71]

%

14 mg/kg/day

[N=34]

%

All PGB

[N=105]

%

Placebo

[N=70]

%Nervous system disorders

Somnolence*

13

21

15

9

Infections and infestations

Pneumonia

1

9

4

0

Viral infection

3

6

4

3

Abbreviations: N=number of patients; PGB=pregabalin.

* includes related terms including lethargy, sluggishness, and hypersomnia.Controlled Studies with Fibromyalgia

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

In clinical trials of patients with fibromyalgia, 19% of patients treated with pregabalin (150 to 600 mg/day) and 10% of patients treated with placebo discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the most common reasons for discontinuation due to adverse reactions were dizziness (6%) and somnolence (3%). In comparison, less than 1% of placebo-treated patients withdrew due to dizziness and somnolence. Other reasons for discontinuation from the trials, occurring with greater frequency in the pregabalin treatment group than in the placebo treatment group, were fatigue, headache, balance disorder, and weight increased. Each of these adverse reactions led to withdrawal in approximately 1% of patients.Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 9 lists all adverse reactions, regardless of causality, occurring in greater than or equal to 2% of patients with fibromyalgia in the ‘all pregabalin’ treatment group for which the incidence was greater than in the placebo treatment group. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in clinical studies experienced adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of "mild" or "moderate".Table 9. Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Trials in Fibromyalgia

System Organ Class Preferred term

150

mg/d [N=132]

%

300

mg/d [N=502]

%

450

mg/d [N=505]

%

600

mg/d [N=378]

%

All PGB*

[N=1,517]

%

Placebo

[N=505]

%

Ear and Labyrinth Disorders

Vertigo

2

2

2

1

2

0

Eye Disorders

Vision blurred

8

7

7

12

8

1

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Dry mouth

7

6

9

9

8

2

Constipation

4

4

7

10

7

2

Vomiting

2

3

3

2

3

2

Flatulence

1

1

2

2

2

1

Abdominal distension

2

2

2

2

2

1

General Disorders and Administrative Site Conditions

Fatigue

5

7

6

8

7

4

Edema peripheral

5

5

6

9

6

2

Chest pain

2

1

1

2

2

1

Feeling abnormal

1

3

2

2

2

0

Edema

1

2

1

2

2

1

Feeling drunk

1

2

1

2

2

0

Infections and Infestations

Sinusitis

4

5

7

5

5

4

Investigations

Weight increased

8

10

10

14

11

2

Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders

Increased appetite

4

3

5

7

5

1

Fluid retention

2

3

3

2

2

1

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders

Arthralgia

4

3

3

6

4

2

Muscle spasms

2

4

4

4

4

2

Back pain

2

3

4

3

3

3

Nervous System Disorders

Dizziness

23

31

43

45

38

9

Somnolence

13

18

22

22

20

4

Headache

11

12

14

10

12

12

Disturbance in attention

4

4

6

6

5

1

Balance disorder

2

3

6

9

5

0

Memory impairment

1

3

4

4

3

0

Coordination abnormal

2

1

2

2

2

1

Hypoesthesia

2

2

3

2

2

1

Lethargy

2

2

1

2

2

0

Tremor

0

1

3

2

2

0

Psychiatric Disorders

Euphoric Mood

2

5

6

7

6

1

Confusional state

0

2

3

4

3

0

Anxiety

2

2

2

2

2

1

Disorientation

1

0

2

1

2

0

Depression

2

2

2

2

2

2

Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders

Pharyngolaryngeal pain

2

1

3

3

2

2* PGB: pregabalin

Controlled Studies in Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord InjuryAdverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation

In clinical trials of adults with neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury, 13% of patients treated with pregabalin and 10% of patients treated with placebo discontinued prematurely due to adverse reactions. In the pregabalin treatment group, the most common reasons for discontinuation due to adverse reactions were somnolence (3%) and edema (2%). In comparison, none of the placebo-treated patients withdrew due to somnolence and edema. Other reasons for discontinuation from the trials, occurring with greater frequency in the pregabalin treatment group than in the placebo treatment group, were fatigue and balance disorder. Each of these adverse reactions led to withdrawal in less than 2% of patients.

Most Common Adverse Reactions

Table 10 lists all adverse reactions, regardless of causality, occurring in greater than or equal to 2% of patients for which the incidence was greater than in the placebo treatment group with neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury in the controlled trials. A majority of pregabalin-treated patients in clinical studies experienced adverse reactions with a maximum intensity of “mild” or “moderate”.

Table 10. Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Trials in Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord Injury

System Organ Class

Preferred term

PGB* (N=182)

Placebo (N=174)

%

%

Ear and labyrinth disorders

Vertigo

2.7

1.1

Eye disorders

Vision blurred

6.6

1.1

Gastrointestinal disorders

Dry mouth

11.0

2.9

Constipation

8.2

5.7

Nausea

4.9

4.0

Vomiting

2.7

1.1

General disorders and administration site conditions

Fatigue

11.0

4.0

Edema peripheral

10.4

5.2

Edema

8.2

1.1

Pain

3.3

1.1

Infections and infestations

Nasopharyngitis

8.2

4.6

Investigations

Weight increased

3.3

1.1

Blood creatine phosphokinase increased

2.7

0

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders

Muscular weakness

4.9

1.7

Pain in extremity

3.3

2.3

Neck pain

2.7

1.1

Back pain

2.2

1.7

Joint swelling

2.2

0

Nervous system disorders

Somnolence

35.7

11.5

Dizziness

20.9

6.9

Disturbance in attention

3.8

0

Memory impairment

3.3

1.1

Paresthesia

2.2

0.6

Psychiatric disorders

Insomnia

3.8

2.9

Euphoric mood

2.2

0.6

Renal and urinary disorders

Urinary incontinence

2.7

1.1

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders

Decubitus ulcer

2.7

1.1

Vascular disorders

Hypertension

2.2

1.1

Hypotension

2.2

0* PGB: Pregabalin

Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Clinical Studies of PregabalinFollowing is a list of treatment-emergent adverse reactions reported by patients treated with pregabalin during all clinical trials. The listing does not include those events already listed in the previous tables or elsewhere in labeling, those events for which a drug cause was remote, those events which were so general as to be uninformative, and those events reported only once which did not have a substantial probability of being acutely life-threatening.

Events are categorized by body system and listed in order of decreasing frequency according to the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring on one or more occasions in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1,000 patients; rare reactions are those occurring in fewer than 1/1,000 patients. Events of major clinical importance are described in the Warnings and Precautions section (5).

Body as a Whole – Frequent: Abdominal pain, Allergic reaction, Fever, Infrequent: Abscess, Cellulitis, Chills, Malaise, Neck rigidity, Overdose, Pelvic pain, Photosensitivity reaction, Rare: Anaphylactoid reaction, Ascites, Granuloma, Hangover effect, Intentional Injury, Retroperitoneal Fibrosis, Shock

Cardiovascular System – Infrequent: Deep thrombophlebitis, Heart failure, Hypotension, Postural hypotension, Retinal vascular disorder, Syncope; Rare: ST Depressed, Ventricular Fibrillation

Digestive System – Frequent: Gastroenteritis, Increased appetite; Infrequent: Cholecystitis, Cholelithiasis, Colitis, Dysphagia, Esophagitis, Gastritis, Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, Melena, Mouth ulceration, Pancreatitis, Rectal hemorrhage, Tongue edema; Rare: Aphthous stomatitis, Esophageal Ulcer, Periodontal abscess

Hemic and Lymphatic System – Frequent: Ecchymosis; Infrequent: Anemia, Eosinophilia, Hypochromic anemia, Leukocytosis, Leukopenia, Lymphadenopathy, Thrombocytopenia; Rare: Myelofibrosis, Polycythemia, Prothrombin decreased, Purpura, Thrombocythemia, Alanine aminotransferase increased, Aspartate aminotransferase increased

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders – Rare: Glucose Tolerance Decreased, Urate Crystalluria

Musculoskeletal System – Frequent: Arthralgia, Leg cramps, Myalgia, Myasthenia; Infrequent: Arthrosis; Rare: Chondrodystrophy, Generalized Spasm

Nervous System – Frequent: Anxiety, Depersonalization, Hypertonia, Hypoesthesia, Libido decreased, Nystagmus, Paresthesia, Sedation, Stupor, Twitching; Infrequent: Abnormal dreams, Agitation, Apathy, Aphasia, Circumoral paresthesia, Dysarthria, Hallucinations, Hostility, Hyperalgesia, Hyperesthesia, Hyperkinesia, Hypokinesia, Hypotonia, Libido increased, Myoclonus, Neuralgia; Rare: Addiction, Cerebellar syndrome, Cogwheel rigidity, Coma, Delirium, Delusions, Dysautonomia, Dyskinesia, Dystonia, Encephalopathy, Extrapyramidal syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Hypalgesia, Intracranial hypertension, Manic reaction, Paranoid reaction, Peripheral neuritis, Personality disorder, Psychotic depression, Schizophrenic reaction, Sleep disorder, Torticollis, Trismus

Respiratory System – Rare: Apnea, Atelectasis, Bronchiolitis, Hiccup, Laryngismus, Lung edema, Lung fibrosis, Yawn

Skin and Appendages – Frequent: Pruritus, Infrequent: Alopecia, Dry skin, Eczema, Hirsutism, Skin ulcer, Urticaria, Vesiculobullous rash; Rare: Angioedema, Exfoliative dermatitis, Lichenoid dermatitis, Melanosis, Nail Disorder, Petechial rash, Purpuric rash, Pustular rash, Skin atrophy, Skin necrosis, Skin nodule, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Subcutaneous nodule

Special senses – Frequent: Conjunctivitis, Diplopia, Otitis media, Tinnitus; Infrequent: Abnormality of accommodation, Blepharitis, Dry eyes, Eye hemorrhage, Hyperacusis, Photophobia, Retinal edema, Taste loss, Taste perversion; Rare: Anisocoria, Blindness, Corneal ulcer, Exophthalmos, Extraocular palsy, Iritis, Keratitis, Keratoconjunctivitis, Miosis, Mydriasis, Night blindness, Ophthalmoplegia, Optic atrophy, Papilledema, Parosmia, Ptosis, Uveitis

Urogenital System – Frequent: Anorgasmia, Impotence, Urinary frequency, Urinary incontinence; Infrequent: Abnormal ejaculation, Albuminuria, Amenorrhea, Dysmenorrhea, Dysuria, Hematuria, Kidney calculus, Leukorrhea, Menorrhagia, Metrorrhagia, Nephritis, Oliguria, Urinary retention, Urine abnormality; Rare: Acute kidney failure, Balanitis, Bladder Neoplasm, Cervicitis, Dyspareunia, Epididymitis, Female lactation, Glomerulitis, Ovarian disorder, Pyelonephritis

Comparison of Gender and Race

The overall adverse event profile of pregabalin was similar between women and men. There are insufficient data to support a statement regarding the distribution of adverse experience reports by race.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of pregabalin. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Nervous System Disorders – Headache

Gastrointestinal Disorders – Nausea, Diarrhea

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders – Gynecomastia, Breast Enlargement

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders – Bullous pemphigoid

There are postmarketing reports of life-threatening or fatal respiratory depression in patients taking pregabalin with opioids or other CNS depressants, or in the setting of underlying respiratory impairment.

In addition, there are postmarketing reports of events related to reduced lower gastrointestinal tract function (e.g., intestinal obstruction, paralytic ileus, constipation) when pregabalin was co-administered with medications that have the potential to produce constipation, such as opioid analgesics.There are postmarketing reports of withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation of pregabalin. Reported adverse reactions include, but are not limited to, seizures, depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, agitation, confusion, disorientation, psychotic symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, nausea, pain, sweating, tremor, headache, dizziness, malaise, and diarrhea.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

Since pregabalin is predominantly excreted unchanged in the urine, undergoes negligible metabolism in humans (less than 2% of a dose recovered in urine as metabolites), and does not bind to plasma proteins, its pharmacokinetics are unlikely to be affected by other agents through metabolic interactions or protein binding displacement. In vitro and in vivo studies showed that pregabalin is unlikely to be involved in significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions. Specifically, there are no pharmacokinetic interactions between pregabalin and the following antiepileptic drugs: carbamazepine, valproic acid, lamotrigine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and topiramate. Important pharmacokinetic interactions would also not be expected to occur between pregabalin and commonly used antiepileptic drugs [see Clinical Pharmacology (12)].

Pharmacodynamics

Multiple oral doses of pregabalin were co-administered with oxycodone, lorazepam, or ethanol. Although no pharmacokinetic interactions were seen, additive effects on cognitive and gross motor functioning were seen when pregabalin was co-administered with these drugs. No clinically important effects on respiration were seen.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to pregabalin during pregnancy. To provide information regarding the effects of in utero exposure to pregabalin, physicians are advised to recommend that pregnant patients taking pregabalin capsules enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry. This can be done by calling the toll free number 1-888-233-2334, and must be done by patients themselves.

Information on the registry can also be found at the website http://www.aedpregnancyregistry.org/.

Risk Summary

Observational studies on the use of pregabalin during pregnancy suggest a possible small increase in the rate of overall major birth defects, but there was no consistent or specific pattern of major birth defects identified (see Data). Available postmarketing data on miscarriage and other maternal, fetal, and long term developmental adverse effects were insufficient to identify risk associated with pregabalin.

Postmarketing data suggest that extended gabapentinoid use with opioids close to delivery may increase the risk of neonatal withdrawal versus opioids alone (see Clinical Considerations). There are no comparative epidemiologic studies evaluating this association. Therefore, it is not known whether exposure to pregabalin alone late in pregnancy may cause withdrawal signs and symptoms.

In animal reproduction studies, increased incidences of fetal structural abnormalities and other manifestations of developmental toxicity, including skeletal malformations, retarded ossification, and decreased fetal body weight were observed in the offspring of rats and rabbits given pregabalin orally during organogenesis, at doses that produced plasma pregabalin exposures (AUC) greater than or equal to 16 times human exposure at the maximum recommended dose (MRD) of 600 mg/day (see Data). In an animal development study, lethality, growth retardation, and nervous and reproductive system functional impairment were observed in the offspring of rats given pregabalin during gestation and lactation. The no-effect dose for developmental toxicity was approximately twice the human exposure at MRD.

The estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated populations are unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 to 4% and 15 to 20%, respectively.

Clinical Considerations

Fetal/Neonatal Adverse Reactions

Neonatal withdrawal syndrome has been reported in newborns exposed to gabapentinoids in utero for an extended period of time when also exposed to opioids close to delivery. Neonatal withdrawal signs and symptoms reported have included tachypnea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypertonia, irritability, sneezing, poor feeding, hyperactivity, abnormal sleep pattern, and tremor. Reported signs and symptoms that may also be related to withdrawal include tongue thrusting, wandering eye movements while awake, back arching, and continuous extremity movements. Observe neonates exposed to pregabalin and opioids for signs and symptoms of neonatal withdrawal and manage accordingly.

Data

Human Data

One database study, which included over 2,700 pregnancies exposed to pregabalin (monotherapy) during the first trimester compared to 3,063,251 pregnancies unexposed to antiepileptics demonstrated prevalence ratios for major malformations overall of 1.14 (CI 95% 0.96 to 1.35) for pregabalin, 1.29 (CI 95% 1.01 to 1.65) for lamotrigine, 1.39 (CI 95% 1.07 to 1.82) for duloxetine, and 1.24 (CI 95% 1.00 to 1.54) for exposure to either lamotrigine or duloxetine. Important study limitations include uncertainty of whether women who filled a prescription took the medication and inability to adequately control for the underlying disease and other potential confounders.

A published study included results from two separate databases. One database, which included 353 pregnancies exposed to pregabalin (monotherapy) during the first trimester compared to 368,489 pregnancies unexposed to antiepileptics, showed no increase in risk of major birth defects; adjusted relative risk 0.87 (CI 95% 0.53 to 1.42). The second database, which included 118 pregnancies exposed to pregabalin (monotherapy) during the first trimester compared to 380,347 pregnancies unexposed to antiepileptics, suggested a small increase in risk of major birth defects; adjusted relative risk 1.26 (CI 95% 0.64 to 2.49). The risk estimates crossed the null, and the study had limitations similar to the prior study.

Other published epidemiologic studies reported inconsistent findings. No specific pattern of birth defects was identified across studies. All of the studies had limitations due to their retrospective design.

Animal Data

When pregnant rats were given pregabalin (500, 1,250, or 2,500 mg/kg) orally throughout the period of organogenesis, incidences of specific skull alterations attributed to abnormally advanced ossification (premature fusion of the jugal and nasal sutures) were increased at greater than or equal to 1,250 mg/kg, and incidences of skeletal variations and retarded ossification were increased at all doses. Fetal body weights were decreased at the highest dose. The low dose in this study was associated with a plasma exposure (AUC) approximately 17 times human exposure at the MRD of 600 mg/day. A no-effect dose for rat embryo-fetal developmental toxicity was not established.

When pregnant rabbits were given pregabalin (250, 500, or 1,250 mg/kg) orally throughout the period of organogenesis, decreased fetal body weight and increased incidences of skeletal malformations, visceral variations, and retarded ossification were observed at the highest dose. The no-effect dose for developmental toxicity in rabbits (500 mg/kg) was associated with a plasma exposure approximately 16 times human exposure at the MRD.

In a study in which female rats were dosed with pregabalin (50, 100, 250, 1,250, or 2,500 mg/kg) throughout gestation and lactation, offspring growth was reduced at greater than or equal to 100 mg/kg and offspring survival was decreased at greater than or equal to 250 mg/kg. The effect on offspring survival was pronounced at doses greater than or equal to 1,250 mg/kg, with 100% mortality in high-dose litters. When offspring were tested as adults, neurobehavioral abnormalities (decreased auditory startle responding) were observed at greater than or equal to 250 mg/kg and reproductive impairment (decreased fertility and litter size) was seen at 1,250 mg/kg. The no-effect dose for pre- and postnatal developmental toxicity in rats (50 mg/kg) produced a plasma exposure approximately 2 times human exposure at the MRD.

In the prenatal-postnatal study in rats, pregabalin prolonged gestation and induced dystocia at exposures greater than or equal to 50 times the mean human exposure (AUC (0 to 24) of 123 mcg∙hr/mL) at the MRD.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

Small amounts of pregabalin have been detected in the milk of lactating women. A pharmacokinetic study in lactating women detected pregabalin in breast milk at average steady state concentrations approximately 76% of those in maternal plasma. The estimated average daily infant dose of pregabalin from breast milk (assuming mean milk consumption of 150 mL/kg/day) was 0.31 mg/kg/day, which on a mg/kg basis would be approximately 7% of the maternal dose (see Data). The study did not evaluate the effects of pregabalin on milk production or the effects of pregabalin on the breastfed infant.

Based on animal studies, there is a potential risk of tumorigenicity with pregabalin exposure via breast milk to the breastfed infant [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)]. Available clinical study data in patients greater than 12 years of age do not provide a clear conclusion about the potential risk of tumorigenicity with pregabalin [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]. Because of the potential risk of tumorigenicity, breastfeeding is not recommended during treatment with pregabalin.

Data

A pharmacokinetic study in ten lactating women, who were at least 12 weeks postpartum, evaluated the concentrations of pregabalin in plasma and breast milk. Pregabalin 150 mg oral capsule was given every 12 hours (300 mg daily dose) for a total of four doses. Pregabalin was detected in breast milk at average steady-state concentrations approximately 76% of those in maternal plasma. The estimated average daily infant dose of pregabalin from breast milk (assuming mean milk consumption of 150 mL/kg/day) was 0.31 mg/kg/day, which on a mg/kg basis would be approximately 7% of the maternal dose. The study did not evaluate the effects of pregabalin on milk production. Infants did not receive breast milk obtained during the dosing period, therefore, the effects of pregabalin on the breast fed infant were not evaluated.

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Infertility

Males

Effects on Spermatogenesis

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled non-inferiority study to assess the effect of pregabalin on sperm characteristics, healthy male subjects received pregabalin at a daily dose up to 600 mg (n=111) or placebo (n=109) for 13 weeks (one complete sperm cycle) followed by a 13-week washout period (off-drug). A total of 65 subjects in the pregabalin group (59%) and 62 subjects in the placebo group (57%) were included in the per protocol (PP) population. These subjects took study drug for at least 8 weeks, had appropriate timing of semen collections and did not have any significant protocol violations. Among these subjects, approximately 9% of the pregabalin group (6/65) vs. 3% in the placebo group (2/62) had greater than or equal to 50% reduction in mean sperm concentrations from baseline at Week 26 (the primary endpoint). The difference between pregabalin and placebo was within the pre-specified non-inferiority margin of 20%. There were no adverse effects of pregabalin on sperm morphology, sperm motility, serum FSH or serum testosterone levels as compared to placebo. In subjects in the PP population with greater than or equal to 50% reduction in sperm concentration from baseline, sperm concentrations were no longer reduced by greater than or equal to 50% in any affected subject after an additional 3 months off-drug. In one subject, however, subsequent semen analyses demonstrated reductions from baseline of greater than or equal to 50% at 9 and 12 months off-drug. The clinical relevance of these data is unknown.

In the animal fertility study with pregabalin in male rats, adverse reproductive and developmental effects were observed [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)].

8.4 Pediatric Use

Neuropathic Pain Associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy, Postherpetic Neuralgia, and Neuropathic Pain Associated with Spinal Cord Injury

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established.

Fibromyalgia

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established.

A 15-week, placebo-controlled trial was conducted with 107 pediatric patients with fibromyalgia, ages 12 through 17 years, at pregabalin total daily doses of 75 to 450 mg per day. The primary efficacy endpoint of change from baseline to Week 15 in mean pain intensity (derived from an 11-point numeric rating scale) showed numerically greater improvement for the pregabalin-treated patients compared to placebo-treated patients, but did not reach statistical significance. The most frequently observed adverse reactions in the clinical trial included dizziness, nausea, headache, weight increased, and fatigue. The overall safety profile in adolescents was similar to that observed in adults with fibromyalgia.Adjunctive Therapy for Partial-Onset Seizures

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients below the age of 1 month have not been established.

4 to Less Than 17 Years of Age with Partial-Onset SeizuresThe safety and effectiveness of pregabalin as adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in pediatric patients 4 to less than 17 years of age have been established in a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (n=295) [see Clinical Studies (14.3)]. Patients treated with pregabalin 10 mg/kg/day had, on average, a 21.0% greater reduction in partial-onset seizures than patients treated with placebo (p=0.0185). Patients treated with pregabalin 2.5 mg/kg/day had, on average, a 10.5% greater reduction in partial-onset seizures than patients treated with placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.2577).

Responder rates (50% or greater reduction in partial-onset seizure frequency) were a key secondary efficacy parameter and showed numerical improvement with pregabalin compared with placebo: the responder rates were 40.6%, 29.1%, and 22.6%, for pregabalin 10 mg/kg/day, pregabalin 2.5 mg/kg/day, and placebo, respectively.

The most common adverse reactions (≥5%) with pregabalin in this study were somnolence, weight increased, and increased appetite [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

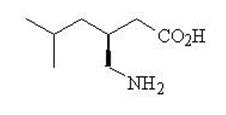

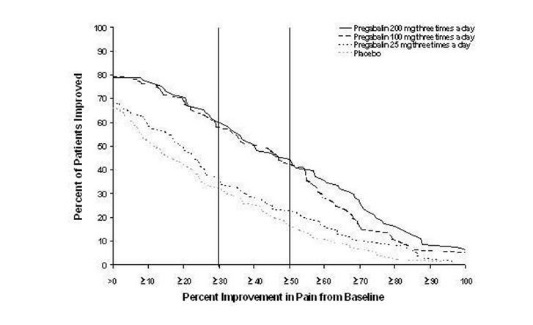

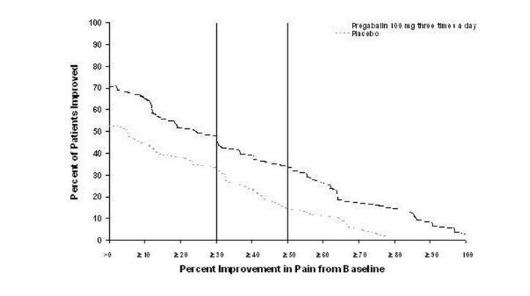

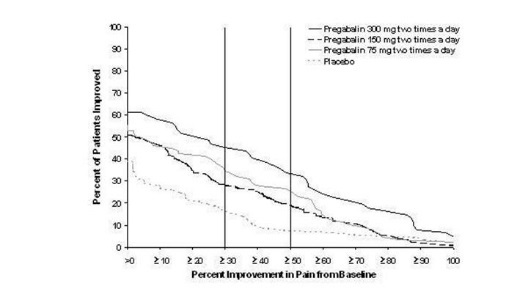

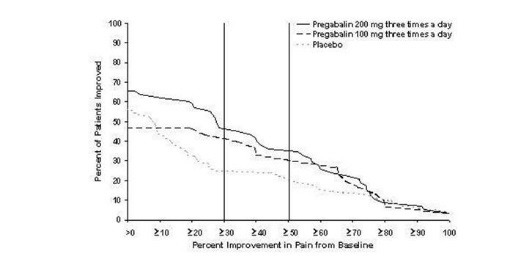

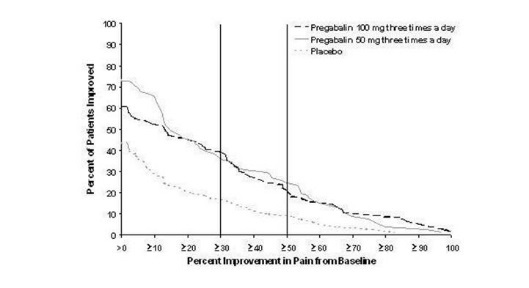

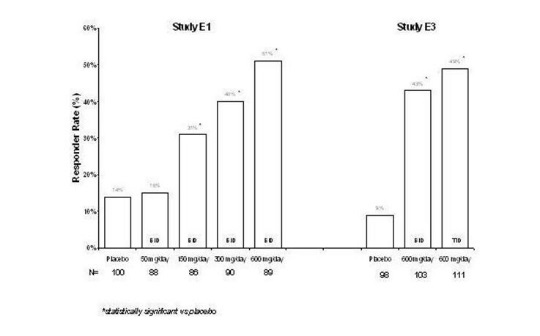

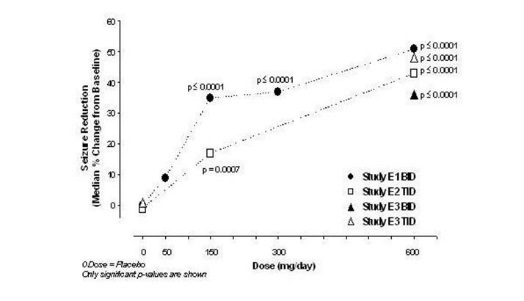

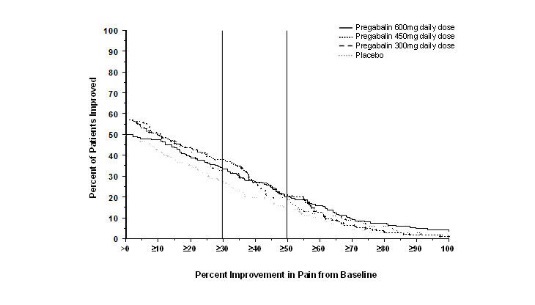

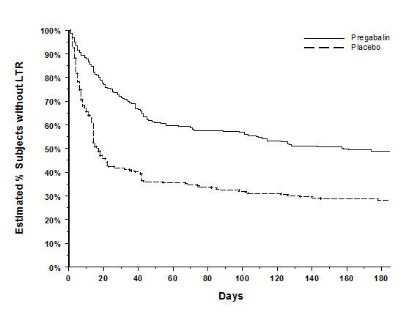

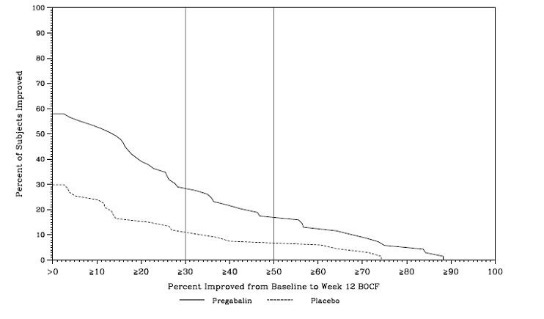

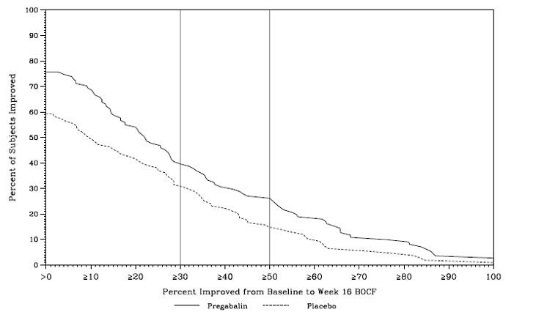

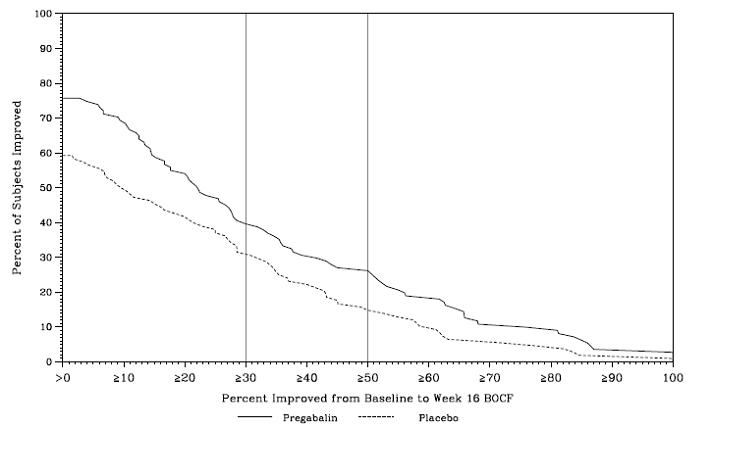

The use of pregabalin 2.5 mg/kg/day in pediatric patients is further supported by evidence from adequate and well-controlled studies in adults with partial-onset seizures and pharmacokinetic data from adult and pediatric patients [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].