NALTREXONE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated

Naltrexone Hydrochloride by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Naltrexone Hydrochloride by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by NuCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

DESCRIPTION

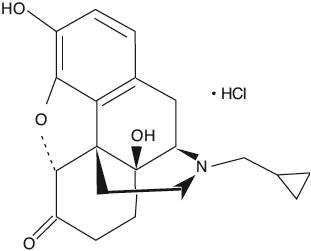

Naltrexone hydrochloride, an opioid antagonist, are a synthetic congener of oxymorphone with no opioid agonist properties. Naltrexone differs in structure from oxymorphone in that the methyl group on the nitrogen atom is replaced by a cyclopropylmethyl group. Naltrexone hydrochloride is also related to the potent opioid antagonist, naloxone, or n-allylnoroxymorphone. The chemical name for naltrexone hydrochloride is Morphinan-6-one, 17-(cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-epoxy-3,14-dihydroxy-, hydrochloride, (5a)-. The structural formula is as follows:

C 20H 23NO 4∙HCl Molecular Weight: 377.86 Naltrexone hydrochloride is a white, crystalline compound. The hydrochloride salt is soluble in water to the extent of about 100 mg/mL. Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets USP are available in scored film-coated tablets containing 50 mg of naltrexone hydrochloride. Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets USP also contain: carnauba wax powder, colloidal silicon dioxide, croscarmellose sodium, hypromellose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, lactose anhydrous, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, polyethylene glycol, titanium dioxide and yellow iron oxide.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacodynamic Actions

Naltrexone hydrochloride is a pure opioid antagonist. It markedly attenuates or completely blocks, reversibly, the subjective effects of intravenously administered opioids.

When co-administered with morphine, on a chronic basis, naltrexone hydrochloride blocks the physical dependence to morphine, heroin and other opioids.

Naltrexone hydrochloride has few, if any, intrinsic actions besides its opioid blocking properties. However, it does produce some pupillary constriction, by an unknown mechanism.

The administration of naltrexone hydrochloride is not associated with the development of tolerance or dependence. In subjects physically dependent on opioids, naltrexone hydrochloride will precipitate withdrawal symptomatology.

Clinical studies indicate that 50 mg of naltrexone hydrochloride will block the pharmacologic effects of 25 mg of intravenously administered heroin for periods as long as 24 hours. Other data suggest that doubling the dose of naltrexone hydrochloride provides blockade for 48 hours, and tripling the dose of naltrexone hydrochloride provides blockade for about 72 hours.

Naltrexone hydrochloride blocks the effects of opioids by competitive binding (i.e., analogous to competitive inhibition of enzymes) at opioid receptors. This makes the blockade produced potentially surmountable, but overcoming full naltrexone blockade by administration of very high doses of opiates has resulted in excessive symptoms of histamine release in experimental subjects.

The mechanism of action of naltrexone hydrochloride in alcoholism is not understood; however, involvement of the endogenous opioid system is suggested by preclinical data. Naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist, competitively binds to such receptors and may block the effects of endogenous opioids. Opioid antagonists have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption by animals, and naltrexone hydrochloride has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption in clinical studies.

Naltrexone hydrochloride is not aversive therapy and does not cause a disulfiram-like reaction either as a result of opiate use or ethanol ingestion.

Pharmacokinetics

Naltrexone hydrochloride is a pure opioid receptor antagonist. Although well absorbed orally, naltrexone is subject to significant first pass metabolism with oral bioavailability estimates ranging from 5 to 40%. The activity of naltrexone is believed to be due to both parent and the 6-β-naltrexol metabolite. Both parent drug and metabolites are excreted primarily by the kidney (53% to 79% of the dose), however, urinary excretion of unchanged naltrexone accounts for less than 2% of an oral dose and fecal excretion is a minor elimination pathway. The mean elimination half-life (T-1/2) values for naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol are 4 hours and 13 hours, respectively. Naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol are dose proportional in terms of AUC and C maxover the range of 50 to 200 mg and do not accumulate after 100 mg daily doses.

Absorption

Following oral administration, naltrexone undergoes rapid and nearly complete absorption with approximately 96% of the dose absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Peak plasma levels of both naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol occur within one hour of dosing.

Distribution

The volume of distribution for naltrexone following intravenous administration is estimated to be 1350 liters. In vitrotests with human plasma show naltrexone to be 21% bound to plasma proteins over the therapeutic dose range.

Metabolism

The systemic clearance (after intravenous administration) of naltrexone is ~3.5 L/min, which exceeds liver blood flow (~1.2 L/min). This suggests both that naltrexone is a highly extracted drug (>98% metabolized) and that extra hepatic sites of drug metabolism exist. The major metabolite of naltrexone is 6-β-naltrexol. Two other minor metabolites are 2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-6-β-naltrexol and 2-hydroxy-3-methyl-naltrexone. Naltrexone and its metabolites are also conjugated to form additional metabolic products.

Elimination

The renal clearance for naltrexone ranges from 30 to 127 mL/min and suggests that renal elimination is primarily by glomerular filtration. In comparison, the renal clearance for 6-β-naltrexol ranges from 230 to 369 mL/min, suggesting an additional renal tubular secretory mechanism. The urinary excretion of unchanged naltrexone accounts for less than 2% of an oral dose; urinary excretion of unchanged and conjugated 6-β-naltrexol accounts for 43% of an oral dose. The pharmacokinetic profile of naltrexone suggests that naltrexone and its metabolites may undergo enterohepatic recycling.

Hepatic and Renal Impairment

Naltrexone appears to have extra-hepatic sites of drug metabolism and its major metabolite undergoes active tubular secretion (see Metabolismabove). Adequate studies of naltrexone in patients with severe hepatic or renal impairment have not been conducted (see PRECAUTIONS, Special Risk Patients).

Clinical Trials

Alcoholism

The efficacy of naltrexone hydrochloride as an aid to the treatment of alcoholism was tested in placebo-controlled, outpatient, double blind trials. These studies used a dose of naltrexone hydrochloride 50 mg once daily for 12 weeks as an adjunct to social and psychotherapeutic methods when given under conditions that enhanced patient compliance. Patients with psychosis, dementia, and secondary psychiatric diagnoses were excluded from these studies.

In one of these studies, 104 alcohol-dependent patients were randomized to receive either naltrexone hydrochloride 50 mg once daily or placebo. In this study, naltrexone hydrochloride proved superior to placebo in measures of drinking including abstention rates (51% vs. 23%), number of drinking days, and relapse (31% vs. 60%). In a second study with 82 alcohol-dependent patients, the group of patients receiving naltrexone hydrochloride were shown to have lower relapse rates (21% vs. 41%), less alcohol craving, and fewer drinking days compared with patients who received placebo, but these results depended on the specific analysis used.

The clinical use of naltrexone hydrochloride as adjunctive pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcoholism was also evaluated in a multicenter safety study. This study of 865 individuals with alcoholism included patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions, concomitant medications, polysubstance abuse and HIV disease. Results of this study demonstrated that the side effect profile of naltrexone hydrochloride appears to be similar in both alcoholic and opioid dependent populations, and that serious side effects are uncommon.

In the clinical studies, treatment with naltrexone supported abstinence, prevented relapse and decreased alcohol consumption. In the uncontrolled study, the patterns of abstinence and relapse were similar to those observed in the controlled studies. Naltrexone hydrochloride was not uniformly helpful to all patients, and the expected effect of the drug is a modest improvement in the outcome of conventional treatment.

Treatment of Opioid Addiction

Naltrexone hydrochloride has been shown to produce complete blockade of the euphoric effects of opioids in both volunteer and addict populations. When administered by means that enforce compliance, it will produce an effective opioid blockade, but has not been shown to affect the use of cocaine or other non-opioid drugs of abuse.

There are no data that demonstrate an unequivocally beneficial effect of naltrexone hydrochloride on rates of recidivism among detoxified, formerly opioid-dependent individuals who self-administer the drug. The failure of the drug in this setting appears to be due to poor medication compliance.

The drug is reported to be of greatest use in good prognosis opioid addicts who take the drug as part of a comprehensive occupational rehabilitative program, behavioral contract, or other compliance-enhancing protocol. Naltrexone hydrochloride, unlike methadone or LAAM (levo-alpha-acetyl-methadol), does not reinforce medication compliance and is expected to have a therapeutic effect only when given under external conditions that support continued use of the medication.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets USP are indicated in the treatment of alcohol dependence and for the blockade of the effects of exogenously administered opioids.

Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets USP have not been shown to provide any therapeutic benefit except as part of an appropriate plan of management for the addictions.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Naltrexone hydrochloride is contraindicated in:

- Patients receiving opioid analgesics.

- Patients currently dependent on opioids, including those currently maintained on opiate agonists (e.g., methadone) or partial agonists (e.g., buprenorphine).

- Patients in acute opioid withdrawal (see WARNINGS).

- Any individual who has failed the naloxone challenge test or who has a positive urine screen for opioids.

- Any individual with a history of sensitivity to naltrexone hydrochloride or any other components of this product. It is not known if there is any cross-sensitivity with naloxone or the phenanthrene containing opioids.

-

WARNINGS

Vulnerability to Opioid Overdose

After opioid detoxification, patients are likely to have reduced tolerance to opioids. As the blockade of exogenous opioids provided by naltrexone hydrochloride wanes and eventually dissipates completely, patients who have been treated with naltrexone hydrochloride may respond to lower doses of opioids than previously used, just as they would shortly after completing detoxification. This could result in potentially life-threatening opioid intoxication (respiratory compromise or arrest, circulatory collapse, etc.) if the patient uses previously tolerated doses of opioids. Cases of opioid overdose with fatal outcomes have been reported in patients after discontinuing treatment.

Patients should be alerted that they may be more sensitive to opioids, even at lower doses, after naltrexone hydrochloride treatment is discontinued. It is important that patients inform family members, and the people closest to the patient of this increased sensitivity ot opioids and the risk of overdose (see PRECAUTIONS, Information for Patients).

There is also the possibility that a patient who is treated with naltrexone hydrochloride could overcome the opioid blockade effect of naltrexone hydrochloride. Although naltrexone hydrochloride is a potent antagonist, the blockade produced by naltrexone hydrochloride is surmountable. The plasma concentration of exogenous opioids attained immediately following their acute administration may be sufficient to overcome the competitive receptor blockade. This poses a potential risk to individuals who attempt, on their own, to overcome the blockade by administering large amounts of exogenous opioids. Any attempt by a patient to overcome the antagonism by taking opioids is especially dangerous and may lead to life-threatening opioid intoxication or fatal overdose. Patients should be told of the serious consequences of trying to overcome the opioid blockade (see PRECAUTIONS, Information for Patients).

Precipitated Opioid Withdrawal

The symptoms of spontaneous opioid withdrawal (which are associated with the discontinuation of opioid in a dependent individual) are uncomfortable, but they are not generally believed to be severe or necessitate hospitalization. However, when withdrawal is precipitated abruptly by the administration of an opioid antagonist to an opioid-dependent patient, the resulting withdrawal syndrome can be severe enough to require hospitalization. Symptoms of withdrawal have usually appeared within five minutes of ingestion of naltrexone hydrochloride and have lasted for up to 48 hours. Mental status changes including confusion, somnolence and visual hallucinations have occurred. Significant fluid losses from vomiting and diarrhea have required intravenous fluid administration. Review of postmarketing cases of precipitated opioid withdrawal in association with naltrexone treatment has identified cases with symptoms of withdrawal severe enough to require hospital admission, and in some cases, management in the intensive care unit.

To prevent occurrence of precipitated withdrawal in patients dependent on opioids, or exacerbation of a pre-existing subclinical withdrawal syndrome, opioid-dependent patients, including those being treated for alcohol dependence, should be opioid-free (including tramadol) before starting naltrexone hydrochloride treatment. An opioid-free interval of a minimum of 7 to 10 days is recommended for patients previously dependent on short-acting opioids. Patients transitioning from buprenorphine or methadone may be vulnerable to precipitation of withdrawal symptoms for as long as two weeks.

If a more rapid transition from agonist to antagonist therapy is deemed necessary and appropriate by the healthcare provider, monitor the patient closely in an appropriate medical setting where precipitated withdrawal can be managed.

In every case, healthcare providers should always be prepared to manage withdrawal symptomatically with non-opioid medications because there is no completely reliable method for determining whether a patient has had an adequate opioid-free period. A naloxone challenge test may be helpful; however, a few case reports have indicated that patients may experience precipitated withdrawal despite having a negative urine toxicology screen or tolerating a naloxone challenge test (usually in the setting of transitioning from buprenorphine treatment). Patients should be made aware of the risks associated with precipitated withdrawal and encouraged to give an accurate account of last opioid use. Patients treated for alcohol dependence with naltrexone hydrochloride should also be assessed for underlying opioid dependence and for any recent use of opioids prior to initiation of treatment with naltrexone hydrochloride. Precipitated opioid withdrawal has been observed in alcohol-dependent patients in circumstances where the prescriber had been unaware of the additional use of opioids or co-dependence on opioids.

Hepatotoxicity

Cases of hepatitis and clinically significant liver dysfunction were observed in association with naltrexone hydrochloride exposure during the clinical development program and in the postmarketing period. Transient, asymptomatic hepatic transaminase elevations were also observed in the clinical trials and postmarketing period. When patients presented with elevated transaminases, there were often other potential causative or contributory etiologies identified, including pre-existing alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B and/or C infection, and concomitant usage of other potentially hepatotoxic drugs. Although clinically significant liver dysfunction is not typically recognized as a manifestation of opioid withdrawal, opioid withdrawal that is precipitated abruptly may lead to systemic sequelae, including acute liver injury.

Patients should be warned of the risk of hepatic injury and advised to seek medical attention if they experience symptoms of acute hepatitis. Use of naltrexone hydrochloride should be discontinued in the event of symptoms and/or signs of acute hepatitis.

Depression and Suicidality

Depression, suicide, attempted suicide and suicidal ideation have been reported in the postmarketing experience with naltrexone hydrochloride used in the treatment of opioid dependence. No causal relationship has been demonstrated. In the literature, endogenous opioids have been theorized to contribute to a variety of conditions.

Alcohol- and opioid-dependent patients, including those taking naltrexone hydrochloride, should be monitored for the development of depression or suicidal thinking. Families and caregivers of patients being treated with naltrexone hydrochloride should be alerted to the need to monitor patients for the emergence of symptoms of depression or suicidality, and to report such symptoms to the patient's healthcare provider.

Ultra Rapid Opioid Withdrawal

Safe use of naltrexone in ultra rapid opiate detoxification programs has not been established (see ADVERSE REACTIONS).

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

When Reversal of Naltrexone Hydrochloride Blockade is Required for Pain Management

In an emergency situation in patients receiving fully blocking doses of naltrexone hydrochloride, a suggested plan of management is regional analgesia, conscious sedation with a benzodiazepine, use of non-opioid analgesics or general anesthesia.

In a situation requiring opioid analgesia, the amount of opioid required may be greater than usual, and the resulting respiratory depression may be deeper and more prolonged.

A rapidly acting opioid analgesic which minimizes the duration of respiratory depression is preferred. The amount of analgesic administered should be titrated to the needs of the patient. Non-receptor mediated actions may occur and should be expected (e.g., facial swelling, itching, generalized erythema, or bronchoconstriction) presumably due to histamine release.

Irrespective of the drug chosen to reverse naltrexone hydrochloride blockade, the patient should be monitored closely by appropriately trained personnel in a setting equipped and staffed for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Special Risk Patients

Renal Impairment

Naltrexone hydrochloride and its primary metabolite are excreted primarily in the urine, and caution is recommended in administering the drug to patients with renal impairment.

Hepatic Impairment

An increase in naltrexone AUC of approximately 5- and 10-fold in patients with compensated and decompensated liver cirrhosis, respectively, compared with subjects with normal liver function has been reported. These data also suggest that alterations in naltrexone bioavailability are related to liver disease severity.

Information for Patients

It is recommended that the prescribing physician relate the following information to patients being treated with naltrexone hydrochloride:

You have been prescribed naltrexone hydrochloride as part of the comprehensive treatment for your alcoholism or drug dependence. You should carry identification to alert medical personnel to the fact that you are taking naltrexone hydrochloride. A naltrexone hydrochloride medication card may be obtained from your physician and can be used for this purpose. Carrying the identification card should help to ensure that you can obtain adequate treatment in an emergency. If you require medical treatment, be sure to tell the treating physician that you are receiving naltrexone hydrochloride therapy. You should take naltrexone hydrochloride as directed by your physician.

- Advise patients that if they previously used opioids, they may be more sensitive to lower doses of opioids and at risk of accidental overdose should they use opioids after naltrexone hydrochloride treatment is discontinued or temporarily interrupted. It is important that patients inform family members and the people closest to the patient of this increased sensitivity to opioids and the risk of overdose.

- Advise patients that because naltrexone hydrochloride can block the effects of opioids, patients will not perceive any effect if they attempt to self-administer heroin or any other opioid drug in small doses while on naltrexone hydrochloride. Further, emphasize that administration of large doses of heroin or any other opioid to try to bypass the blockade and get high while on naltrexone hydrochloride may lead to serious injury, coma or death.

- Patients on naltrexone hydrochloride may not experience the expected effects from opioid-containing analgesic, antidiarrheal, or antitussive medications.

- Patients should be off all opioids, including opioid-containing medicines, for a minimum or 7 to 10 days before starting naltrexone hydrochloride in order to avoid precipitation of opioid withdrawal. Patients transitioning from buprenorphine or methadone may be vulnerable to precipitation of withdrawal symptoms for as long as two weeks. Ensure that patients understand that withdrawal precipitated by administration of an opioid antagonist may be severe enough to require hospitalization if they have not been opioid-free for an adequate period of time, and is different from the experience of spontaneous withdrawal that occurs with discontinuation of opioid in a dependent individual. Advise patients that they should not take naltrexone hydrochloride if they have symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Advise all patients, including those with alcohol dependence, that it is imperative to notify healthcare providers of any recent use of opioids or any history of opioid dependence before starting naltrexone hydrochloride to avoid precipitation of opioid withdrawal.

- Advise patients that naltrexone hydrochloride may cause liver injury. Patients should immediately notify their physician if they develop symptoms and/or signs of liver disease.

- Advise patients that they may experience depression while taking naltrexone hydrochloride. It is important that patients inform family members and the people closest to the patient that they are taking naltrexone hydrochloride and that they should call a doctor right way should they become depressed or experience symptoms of depression.

- Advise patients that naltrexone hydrochloride has been shown to be effective only when used as part of a treatment program that includes counseling and support.

- Advise patients that dizziness may occur with naltrexone hydrochloride treatment, and they should avoid driving or operating heavy machinery until they have determined how naltrexone hydrochloride affects them.

- Advise patients to notify their physician if they:

- become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during treatment with naltrexone hydrochloride.

- are breastfeeding.

- experience other unusual or significant side effects while on naltrexone hydrochloride therapy.

Laboratory Tests

Naltrexone hydrochloride does not interfere with thin-layer, gas-liquid, and high pressure liquid chromatographic methods which may be used for the separation and detection of morphine, methadone or quinine in the urine. Naltrexone hydrochloride may or may not interfere with enzymatic methods for the detection of opioids depending on the specificity of the test. Please consult the test manufacturer for specific details.

Drug Interactions

Studies to evaluate possible interactions between naltrexone hydrochloride and drugs other than opiates have not been performed. Consequently, caution is advised if the concomitant administration of naltrexone hydrochloride and other drugs is required.

The safety and efficacy of concomitant use of naltrexone hydrochloride and disulfiram is unknown, and the concomitant use of two potentially hepatotoxic medications is not ordinarily recommended unless the probable benefits outweigh the known risks.

Lethargy and somnolence have been reported following doses of naltrexone hydrochloride and thioridazine.

Patients taking naltrexone hydrochloride may not benefit from opioid containing medicines, such as cough and cold preparations, antidiarrheal preparations, and opioid analgesics. In an emergency situation when opioid analgesia must be administered to a patient receiving naltrexone hydrochloride, the amount of opioid required may be greater than usual, and the resulting respiratory depression may be deeper and more prolonged (see PRECAUTIONS).

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis and Impairment of Fertility

The following statements are based on the results of experiments in mice and rats. The potential carcinogenic, mutagenic and fertility effects of the metabolite 6-β-naltrexol are unknown.

In a two-year carcinogenicity study in rats, there were small increases in the numbers of testicular mesotheliomas in males and tumors of vascular origin in males and females. The incidence of mesothelioma in males given naltrexone at a dietary dose of 100 mg/kg/day (600 mg/m 2/day; 16 times the recommended therapeutic dose, based on body surface area) was 6%, compared with a maximum historical incidence of 4%. The incidence of vascular tumors in males and females given dietary doses of 100 mg/kg/day (600 mg/m 2/day) was 4% but only the incidence in females was increased compared with a maximum historical control incidence of 2%. There was no evidence of carcinogenicity in a two-year dietary study with naltrexone in male and female mice.

There was limited evidence of a weak genotoxic effect of naltrexone in one gene mutation assay in a mammalian cell line, in the Drosophilarecessive lethal assay, and in non-specific DNA repair tests with E. coli. However, no evidence of genotoxic potential was observed in a range of other in vitrotests, including assays for gene mutation in bacteria, yeast, or in a second mammalian cell line, a chromosomal aberration assay, and an assay for DNA damage in human cells. Naltrexone did not exhibit clastogenicity in an in vivomouse micronucleus assay.

Naltrexone (100 mg/kg/day [600 mg/m 2/day] PO; 16 times the recommended therapeutic dose, based on body surface area) caused a significant increase in pseudopregnancy in the rat. A decrease in the pregnancy rate of mated female rats also occurred. There was no effect on male fertility at this dose level. The relevance of these observations to human fertility is not known.

Pregnancy

Teratogenic Effects

Category C

Naltrexone has been shown to increase the incidence of early fetal loss when given to rats at doses ≥30 mg/kg/day (180 mg/m 2/day; 5 times the recommended therapeutic dose, based on body surface area) and to rabbits at oral doses ≥60 mg/kg/day (720 mg/m 2/day; 18 times the recommended therapeutic dose, based on body surface area). There was no evidence of teratogenicity when naltrexone was administered orally to rats and rabbits during the period of major organogenesis at doses up to 200 mg/kg/day (32 and 65 times the recommended therapeutic dose, respectively, based on body surface area).

Rats do not form appreciable quantities of the major human metabolite, 6-β-naltrexol; therefore, the potential reproductive toxicity of the metabolites in rats is not known.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Naltrexone should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Labor and Delivery

Whether or not naltrexone hydrochloride affects the duration of labor and delivery is unknown.

Nursing Mothers

In animal studies, naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol were excreted in the milk of lactating rats dosed orally with naltrexone.

Whether or not naltrexone hydrochloride is excreted in human milk is unknown. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk, caution should be exercised when naltrexone is administered to a nursing woman.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

During two randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled 12-week trials to evaluate the efficacy of naltrexone hydrochloride as an adjunctive treatment of alcohol dependence, most patients tolerated naltrexone hydrochloride well. In these studies, a total of 93 patients received naltrexone hydrochloride at a dose of 50 mg once daily. Five of these patients discontinued naltrexone hydrochloride because of nausea. No serious adverse events were reported during these two trials.

While extensive clinical studies evaluating the use of naltrexone hydrochloride in detoxified, formerly opioid-dependent individuals failed to identify any single, serious untoward risk of naltrexone hydrochloride use, placebo-controlled studies employing up to five fold higher doses of naltrexone hydrochloride (up to 300 mg per day) than that recommended for use in opiate receptor blockade have shown that naltrexone hydrochloride causes hepatocellular injury in a substantial proportion of patients exposed at higher doses (see WARNINGSand PRECAUTIONS, Laboratory Tests).

Aside from this finding, and the risk of precipitated opioid withdrawal, available evidence does not incriminate naltrexone hydrochloride, used at any dose, as a cause of any other serious adverse reaction for the patient who is "opioid-free." It is critical to recognize that naltrexone hydrochloride can precipitate or exacerbate abstinence signs and symptoms in any individual who is not completely free of exogenous opioids.

Patients with addictive disorders, especially opioid addiction, are at risk for multiple numerous adverse events and abnormal laboratory findings, including liver function abnormalities. Data from both controlled and observational studies suggest that these abnormalities, other than the dose-related hepatotoxicity described above, are not related to the use of naltrexone hydrochloride.

Among opioid-free individuals, naltrexone hydrochloride administration at the recommended dose has not been associated with a predictable profile of serious adverse or untoward events. However, as mentioned above, among individuals using opioids, naltrexone hydrochloride may cause serious withdrawal reactions (see CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS, DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Reported Adverse Events

Naltrexone hydrochloride has not been shown to cause significant increases in complaints in placebo-controlled trials in patients known to be free of opioids for more than 7 to 10 days. Studies in alcoholic populations and in volunteers in clinical pharmacology studies have suggested that a small fraction of patients may experience an opioid withdrawal-like symptom complex consisting of tearfulness, mild nausea, abdominal cramps, restlessness, bone or joint pain, myalgia, and nasal symptoms. This may represent the unmasking of occult opioid use, or it may represent symptoms attributable to naltrexone. A number of alternative dosing patterns have been recommended to try to reduce the frequency of these complaints.

Alcoholism

In an open label safety study with approximately 570 individuals with alcoholism receiving naltrexone hydrochloride, the following new-onset adverse reactions occurred in 2% or more of the patients: nausea (10%), headache (7%), dizziness (4%), nervousness (4%), fatigue (4%), insomnia (3%), vomiting (3%), anxiety (2%) and somnolence (2%).

Depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempts have been reported in all groups when comparing naltrexone, placebo, or controls undergoing treatment for alcoholism.

RATE RANGES OF NEW ONSET EVENTS Naltrexone Placebo Depression 0 to 15% 0 to 17% Suicide Attempt/Ideation 0 to 1% 0 to 3% Although no causal relationship with naltrexone hydrochloride is suspected, physicians should be aware that treatment with naltrexone does not reduce the risk of suicide in these patients (see PRECAUTIONS).

Opioid Addiction

The following adverse reactions have been reported both at baseline and during the naltrexone hydrochloride clinical trials in opioid addiction at an incidence rate of more than 10%:

Difficulty sleeping, anxiety, nervousness, abdominal pain/cramps, nausea and/or vomiting, low energy, joint and muscle pain, and headache.

The incidence was less than 10% for:

Loss of appetite, diarrhea, constipation, increased thirst, increased energy, feeling down, irritability, dizziness, skin rash, delayed ejaculation, decreased potency, and chills.

The following events occurred in less than 1% of subjects:

Respiratory

Nasal congestion, itching, rhinorrhea, sneezing, sore throat, excess mucus or phlegm, sinus trouble, heavy breathing, hoarseness, cough, shortness of breath.Cardiovascular

Nose bleeds, phlebitis, edema, increased blood pressure, non-specific ECG changes, palpitations, tachycardia.Gastrointestinal

Excessive gas, hemorrhoids, diarrhea, ulcer.Musculoskeletal

Painful shoulders, legs or knees; tremors, twitching.Genitourinary

Increased frequency of, or discomfort during, urination; increased or decreased sexual interest.Dermatologic

Oily skin, pruritus, acne, athlete's foot, cold sores, alopecia.Psychiatric

Depression, paranoia, fatigue, restlessness, confusion, disorientation, hallucinations, nightmares, bad dreams.Special senses

Eyes blurred, burning, light sensitive, swollen, aching, strained; ears–"clogged," aching, tinnitus.General

Increased appetite, weight loss, weight gain, yawning, somnolence, fever, dry mouth, head "pounding," inguinal pain, swollen glands, "side" pains, cold feet, "hot spells."Post-marketing Experience

Data collected from post-marketing use of naltrexone hydrochloride show that most events usually occur early in the course of drug therapy and are transient. It is not always possible to distinguish these occurrences from those signs and symptoms that may result from a withdrawal syndrome.

Events that have been reported include anorexia, asthenia, chest pain, fatigue, headache, hot flushes, malaise, changes in blood pressure, agitation, dizziness, hyperkinesia, nausea, vomiting, tremor, abdominal pain, diarrhea, elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin, hepatic function abnormalities or hepatitis, palpitations, myalgia, anxiety, confusion, euphoria, hallucinations, insomnia, nervousness, somnolence, abnormal thinking, dyspnea, rash, increased sweating, vision abnormalities and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

In some individuals the use of opioid antagonists has been associated with a change in baseline levels of some hypothalamic, pituitary, adrenal, or gonadal hormones. The clinical significance of such changes is not fully understood.

Adverse events, including withdrawal symptoms and death, have been reported with the use of naltrexone hydrochloride in ultra rapid opiate detoxification programs. The cause of death in these cases is not known (see WARNINGS).

Laboratory Tests

In a placebo controlled study in which naltrexone hydrochloride was administered to obese subjects at a dose approximately five-fold that recommended for the blockade of opiate receptors (300 mg per day), 19% (5/26) of naltrexone hydrochloride recipients and 0% (0/24) of placebo-treated patients developed elevations in serum transaminases (i.e. peak ALT values ranging from 121 to 532; or 3 to 19 times their baseline values) after three to eight weeks of treatment. The patients involved were generally clinically asymptomatic, and the transaminase levels of all patients on whom follow-up was obtained returned to (or toward) baseline values in a matter of weeks.

Transaminase elevations were also observed in other placebo controlled studies in which exposure to naltrexone hydrochloride at doses above the amount recommended for the treatment of alcoholism or opioid blockade consistently produced more numerous and more significant elevations of serum transaminases than did placebo. Transaminase elevations occurred in 3 of 9 patients with Alzheimer's Disease who received naltrexone hydrochloride (at doses up to 300 mg/day) for 5 to 8 weeks in an open clinical trial.

- DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

-

OVERDOSAGE

There is limited clinical experience with naltrexone hydrochloride overdosage in humans. In one study, subjects who received 800 mg daily of naltrexone hydrochloride for up to one week showed no evidence of toxicity.

In the mouse, rat and guinea pig, the oral LD50s were 1,100 to 1,550 mg/kg; 1,450 mg/kg; and 1,490 mg/kg; respectively. High doses of naltrexone hydrochloride (generally ÿ1,000 mg/kg) produced salivation, depression/reduced activity, tremors, and convulsions. Mortalities in animals due to high-dose naltrexone hydrochloride administration usually were due to clonic-tonic convulsions and/or respiratory failure.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

To reduce the risk of precipitated withdrawal in patients dependent on opioids, or exacerbation of a preexisting subclinical withdrawal syndrome, opioid-dependent patients, including those being treated for alcohol dependence, should be opioid-free (including tramadol) before starting naltrexone hydrochloride tablets treatment. An opioid-free interval of a minimum of 7 to 10 days is recommended for patients previously dependent on short-acting opioids.

Switching from Buprenorphine, Buprenorphine/Naloxone, or Methadone

There are no systematically collected data that specifically address the switch from buprenorphine or methadone to naltrexone hydrochloride tablets; however, review of postmarketing case reports have indicated that some patients may experience severe manifestations of precipitated withdrawal when being switched from opioid agonist therapy to opioid antagonist therapy (see WARNINGS). Patients transitioning from buprenorphine or methadone may be vulnerable to precipitation of withdrawal symptoms for as long as 2 weeks. Healthcare providers should be prepared to manage withdrawal symptomatically with non-opioid medications.

Treatment of Alcoholism

A dose of 50 mg once daily is recommended for most patients. The placebo-controlled studies that demonstrated the efficacy of naltrexone hydrochloride as an adjunctive treatment of alcoholism used a dose regimen of naltrexone hydrochloride 50 mg once daily for up to 12 weeks. Other dose regimens or durations of therapy were not evaluated in these trials.

Naltrexone hydrochloride tablets should be considered as only one of many factors determining the success of treatment of alcoholism. Factors associated with a good outcome in the clinical trials with naltrexone hydrochloride tablets were the type, intensity, and duration of treatment; appropriate management of comorbid conditions; use of community-based support groups; and good medication compliance. To achieve the best possible treatment outcome, appropriate compliance-enhancing techniques should be implemented for all components of the treatment program, especially medication compliance.

Treatment of Opioid Dependence

Treatment should be initiated with an initial dose of 25 mg of naltrexone hydrochloride tablets. If no withdrawal signs occur, the patient may be started on 50 mg a day thereafter.

A dose of 50 mg once a day will produce adequate clinical blockade of the actions of parenterally administered opioids. As with many non-agonist treatments for addiction, naltrexone hydrochloride tablets are of proven value only when given as part of a comprehensive plan of management that includes some measure to ensure the patient takes the medication.

Naloxone Challenge Test:

Clinicians are reminded that there is no completely reliable method for determining whether a patient has had an adequate opioid-free period. A naloxone challenge test may be helpful if there is any question of occult opioid dependence. If signs of opioid withdrawal are still observed following naloxone challenge, treatment with naltrexone hydrochloride tablets should not be attempted. The naloxone challenge can be repeated in 24 hours.

The naloxone challenge test should not be performed in a patient showing clinical signs or symptoms of opioid withdrawal, or in a patient whose urine contains opioids. The naloxone challenge test may be administered by either the intravenous or subcutaneous routes.

Interpretation of the Challenge

Monitor vital signs and observe the patient for signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal. These may include, but are not limited to: nausea, vomiting, dysphoria, yawning, sweating, tearing, rhinorrhea, stuffy nose, craving for opioids, poor appetite, abdominal cramps, sense of fear, skin erythema, disrupted sleep patterns, fidgeting, uneasiness, poor ability to focus, mental lapses, muscle aches or cramps, pupillary dilation, piloerection, fever, changes in blood pressure, pulse or temperature, anxiety, depression, irritability, backache, bone or joint pains, tremors, sensations of skin crawling or fasciculations. If signs or symptoms of withdrawal appear, the test is positive and no additional naloxone should be administered.

Warning: If the test is positive, do NOT initiate naltrexone therapy.Repeat the challenge in 24 hours. If the test is negative, naltrexone therapy may be started if no other contraindications are present. If there is any doubt about the result of the test, hold naltrexone hydrochloride tablets and repeat the challenge in 24 hours.

Alternative Dosing Schedules

A flexible approach to a dosing regimen may need to be employed in cases of supervised administration. Thus, patients may receive 50 mg of naltrexone hydrochloride every weekday with a 100 mg dose on Saturday, 100 mg every other day, or 150 mg every third day. The degree of blockade produced by naltrexone hydrochloride may be reduced by these extended dosing intervals.

There may be a higher risk of hepatocellular injury with single doses above 50 mg, and use of higher doses and extended dosing intervals should balance the possible risks against the probable benefits (see WARNINGS).

Patient Compliance

Naltrexone hydrochloride tablets should be considered as only one of many factors determining the success of treatment. To achieve the best possible treatment outcome, appropriate compliance-enhancing techniques should be implemented for all components of the treatment program, including medication compliance.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP are available as:

50 mg; yellow, round film-coated tablets, bisected on one side, debossed with "EL" on one side of the bisect and "15" on the other side of the bisect. They are available in bottles of:

30 NDC: 68071-3654-3 -

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

These are not all the possible side effects of Naltrexone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to Elite Laboratories, Inc., at 1-888-852-6657 or to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088. For more information go to fda.report.

For inquiries call Precision Dose, Inc. at 1-800-397-9228 or e-mail druginfo@precisiondose.com

Manufactured by:

Elite Laboratories, Inc.

Northvale, NJ 07647Distributed by:

Precision Dose, Inc.

South Beloit, IL 61080Issued 11/23

MF300ISS11/23

OE1315

IN0553 - PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 50 mg Tablet Bottle Label

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

NALTREXONE HYDROCHLORIDE

naltrexone hydrochloride tablet, film coatedProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 68071-3654(NDC:68094-909) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength NALTREXONE HYDROCHLORIDE (UNII: Z6375YW9SF) (NALTREXONE - UNII:5S6W795CQM) NALTREXONE HYDROCHLORIDE 50 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) CROSCARMELLOSE SODIUM (UNII: M28OL1HH48) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) HYDROXYPROPYL CELLULOSE (1600000 WAMW) (UNII: RFW2ET671P) ANHYDROUS LACTOSE (UNII: 3SY5LH9PMK) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) MICROCRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) FERRIC OXIDE YELLOW (UNII: EX438O2MRT) Product Characteristics Color yellow Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND Size 10mm Flavor Imprint Code EL;15 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 68071-3654-3 30 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 07/24/2024 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075274 02/15/2024 Labeler - NuCare Pharmaceuticals Inc. (010632300) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations NuCare Pharmaceuticals Inc. 010632300 relabel(68071-3654)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.