MYCOBUTIN- rifabutin capsule

Mycobutin by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Mycobutin by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Department of State Health Services, Pharmacy Branch. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

MYCOBUTIN Capsules for oral administration contain 150 mg of the rifamycin antimycobacterial agent rifabutin, USP, per capsule, along with the inactive ingredients microcrystalline cellulose, magnesium stearate, red iron oxide, silica gel, sodium lauryl sulfate, titanium dioxide, and edible white ink.

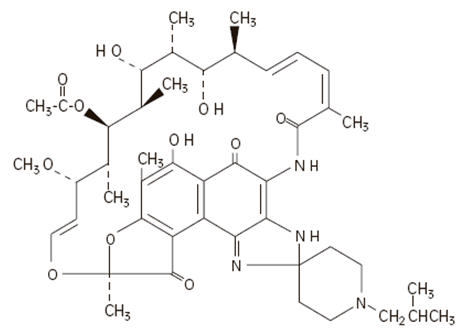

The chemical name for rifabutin is 1',4-didehydro-1-deoxy-1,4-dihydro-5'-(2-methylpropyl)-1-oxorifamycin XIV (Chemical Abstracts Service, 9th Collective Index) or (9 S,12 E,14 S,15 R, 16 S,17 R,18 R,19 R,20 S,21 S,22 E, 24 Z)-6,16,18,20-tetrahydroxy-1'-isobutyl-14-methoxy-7,9,15,17,19,21,25-heptamethyl-spiro [9,4-(epoxypentadeca[1,11,13]trienimino)-2 H-furo[2',3':7,8]naphth[1,2-d] imidazole-2,4'-piperidine]-5,10,26-(3 H,9 H)-trione-16-acetate. Rifabutin has a molecular formula of C 46H 62N 4O 11, a molecular weight of 847.02 and the following structure:

Rifabutin is a red-violet powder soluble in chloroform and methanol, sparingly soluble in ethanol, and very slightly soluble in water (0.19 mg/mL). Its log P value (the base 10 logarithm of the partition coefficient between n-octanol and water) is 3.2 (n-octanol/water).

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Following a single oral dose of 300 mg to nine healthy adult volunteers, rifabutin was readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract with mean (±SD) peak plasma levels (C max) of 375 (±267) ng/mL (range: 141 to 1033 ng/mL) attained in 3.3 (±0.9) hours (T max range: 2 to 4 hours). Absolute bioavailability assessed in five HIV-positive patients, who received both oral and intravenous doses, averaged 20%. Total recovery of radioactivity in the urine indicates that at least 53% of the orally administered rifabutin dose is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. The bioavailability of rifabutin from the capsule dosage form, relative to an oral solution, was 85% in 12 healthy adult volunteers. High-fat meals slow the rate without influencing the extent of absorption from the capsule dosage form. Plasma concentrations post-C max declined in an apparent biphasic manner. Pharmacokinetic dose-proportionality was established over the 300 mg to 600 mg dose range in nine healthy adult volunteers (crossover design) and in 16 early symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients over a 300 mg to 900 mg dose range.

Distribution

Due to its high lipophilicity, rifabutin demonstrates a high propensity for distribution and intracellular tissue uptake. Following intravenous dosing, estimates of apparent steady-state distribution volume (9.3 ± 1.5 L/kg) in five HIV-positive patients exceeded total body water by approximately 15-fold. Substantially higher intracellular tissue levels than those seen in plasma have been observed in both rat and man. The lung-to-plasma concentration ratio, obtained at 12 hours, was approximately 6.5 in four surgical patients who received an oral dose. Mean rifabutin steady-state trough levels (C p,minss; 24-hour post-dose) ranged from 50 to 65 ng/mL in HIV-positive patients and in healthy adult volunteers. About 85% of the drug is bound in a concentration-independent manner to plasma proteins over a concentration range of 0.05 to 1 µg/mL. Binding does not appear to be influenced by renal or hepatic dysfunction. Rifabutin was slowly eliminated from plasma in seven healthy adult volunteers, presumably because of distribution-limited elimination, with a mean terminal half-life of 45 (±17) hours (range: 16 to 69 hours). Although the systemic levels of rifabutin following multiple dosing decreased by 38%, its terminal half-life remained unchanged.

Metabolism

Of the five metabolites that have been identified, 25-O-desacetyl and 31-hydroxy are the most predominant, and show a plasma metabolite:parent area under the curve ratio of 0.10 and 0.07, respectively. The former has an activity equal to the parent drug and contributes up to 10% to the total antimicrobial activity.

Excretion

A mass-balance study in three healthy adult volunteers with 14C-labeled rifabutin showed that 53% of the oral dose was excreted in the urine, primarily as metabolites. About 30% of the dose is excreted in the feces. Mean systemic clearance (CL s/F) in healthy adult volunteers following a single oral dose was 0.69 (±0.32) L/hr/kg (range: 0.46 to 1.34 L/hr/kg). Renal and biliary clearance of unchanged drug each contribute approximately 5% to CL s/F.

Pharmacokinetics in Special Populations

Geriatric

Compared to healthy volunteers, steady-state kinetics of MYCOBUTIN are more variable in elderly patients (>70 years).

Pediatric

The pharmacokinetics of MYCOBUTIN have not been studied in subjects under 18 years of age.

Renal Impairment

The disposition of rifabutin (300 mg) was studied in 18 patients with varying degrees of renal function. Area under plasma concentration time curve (AUC) increased by about 71% in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min) compared to patients with creatinine clearance (Cr cl) between 61–74 mL/min. In patients with mild to moderate renal impairment (Cr cl between 30–61 mL/min), the AUC increased by about 41%. In patients with severe renal impairment, carefully monitor for rifabutin associated adverse events. A reduction in the dosage of rifabutin is recommended for patients with Cr cl <30 mL/min if toxicity is suspected (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Hepatic Impairment

Mild hepatic impairment does not require a dose modification. The pharmacokinetics of rifabutin in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment is not known.

Malabsorption in HIV-Infected Patients

Alterations in gastric pH due to progressing HIV disease has been linked with malabsorption of some drugs used in HIV-positive patients (e.g., rifampin, isoniazid). Drug serum concentrations data from AIDS patients with varying disease severity (basedon CD4+ counts) suggests that rifabutin absorption is not influenced by progressing HIV disease.

Drug-Drug Interactions

(see also PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions)

Multiple dosing of rifabutin has been associated with induction of hepatic metabolic enzymes of the CYP3A subfamily. Rifabutin's predominant metabolite (25-desacetyl rifabutin: LM565), may also contribute to this effect. Metabolic induction due to rifabutin is likely to produce a decrease in plasma concentrations of concomitantly administered drugs that are primarily metabolized by the CYP3A enzymes. Similarly concomitant medications that competitively inhibit the CYP3A activity may increase plasma concentrations of rifabutin.

-

CLINICAL STUDIES

Two randomized, double-blind clinical trials (Study 023 and Study 027) compared MYCOBUTIN (300 mg/day) to placebo in patients with CDC-defined AIDS and CD4 counts ≤200 cells/µL. These studies accrued patients from 2/90 through 2/92. Study 023 enrolled 590 patients, with a median CD4 cell count at study entry of 42 cells/µL (mean 61). Study 027 enrolled 556 patients with a median CD4 cell count at study entry of 40 cells/µL (mean 58).

Endpoints included the following:

- MAC bacteremia, defined as at least one blood culture positive for Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) bacteria.

- Clinically significant disseminated MAC disease, defined as MAC bacteremia accompanied by signs or symptoms of serious MAC infection, including one or more of the following: fever, night sweats, rigors, weight loss, worsening anemia, and/or elevations in alkaline phosphatase.

- Survival.

MAC Bacteremia

Participants who received MYCOBUTIN were one-third to one-half as likely to develop MAC bacteremia as were participants who received placebo. These results were statistically significant (Study 023: p<0.001; Study 027: p = 0.002).

In Study 023, the one-year cumulative incidence of MAC bacteremia, on an intent to treat basis, was 9% for patients randomized to MYCOBUTIN and 22% for patients randomized to placebo. In Study 027, these rates were 13% and 28% for patients receiving MYCOBUTIN and placebo, respectively.

Most cases of MAC bacteremia (approximately 90% in these studies) occurred among participants whose CD4 count at study entry was ≤100 cells/µL. The median and mean CD4 counts at onset of MAC bacteremia were 13 cells/µL and 24 cells/µL, respectively. These studies did not investigate the optimal time to begin MAC prophylaxis.

Clinically Significant Disseminated MAC Disease

In association with the decreased incidence of bacteremia, patients on MYCOBUTIN showed reductions in the signs and symptoms of disseminated MAC disease, including fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, abdominal pain, anemia, and hepatic dysfunction.

-

MICROBIOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

Rifabutin inhibits DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in susceptible strains of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis but not in mammalian cells. In resistant strains of E. coli, rifabutin, like rifampin, did not inhibit this enzyme. It is not known whether rifabutin inhibits DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in Mycobacterium avium or in M. intracellulare which comprise M. avium complex (MAC).

Susceptibility Testing

In vitro susceptibility testing methods and diagnostic products used for determining minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against M. avium complex (MAC) organisms have not been standardized. Breakpoints to determine whether clinical isolates of MAC and other mycobacterial species are susceptible or resistant to rifabutin have not been established.

In Vitro Studies

Rifabutin has demonstrated in vitro activity against M. avium complex (MAC) organisms isolated from both HIV-positive and HIV-negative people. While-gene probe techniques may be used to identify these two organisms, many reported studies did not distinguish between these two species. The vast majority of isolates from MAC-infected, HIV-positive people are M. avium, whereas in HIV-negative people, about 40% of the MAC isolates are M. intracellulare.

Various in vitro methodologies employing broth or solid media, with and without polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), have been used to determine rifabutin MIC values for mycobacterial species. In general, MIC values determined in broth are several fold lower than that observed with methods employing solid media. Utilization of Tween 80 in these assays has been shown to further lower MIC values.

However, MIC values were substantially higher for egg-based compared to agar-based solid media.

Rifabutin activity against 211 MAC isolates from HIV-positive people was evaluated in vitro utilizing a radiometric broth and an agar dilution method. Results showed that 78% and 82% of these isolates had MIC 99 values of ≤0.25 µg/mL and ≤1.0 µg/mL, respectively, when evaluated by these two methods. Rifabutin was also shown to be active against phagocytized, M. avium complex in a mouse macrophage cell culture model.

Rifabutin has in vitro activity against many strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In one study, utilizing the radiometric broth method, each of 17 and 20 rifampin-naive clinical isolates tested from the United States and Taiwan, respectively, were shown to be susceptible to rifabutin concentrations of ≤0.125 µg/mL.

Cross-resistance between rifampin and rifabutin is commonly observed with M. tuberculosis and M. avium complex isolates. Isolates of M. tuberculosis resistant to rifampin are likely to be resistant to rifabutin. Rifampicin and rifabutin MIC 99 values against 523 isolates of M. avium complex were determined utilizing the agar dilution method (Heifets, Leonid B. and Iseman, Michael D. Determination of in vitro susceptibility of Mycobacteria to Ansamycin. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1985; 132(3):710–711).

Table 1 Susceptibility of M. Avium Complex Strains to Rifampin and Rifabutin % of Strains Susceptible/Resistant to Different Concentrations of Rifabutin (μg/mL) Susceptibility to Rifampin

(µg/mL)Number of Strains Susceptible to 0.5 Resistant to 0.5 only Resistant to 1.0 Resistant to 2.0 Susceptible to 1.0 30 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Resistant to 1.0 only 163 88.3 11.7 0.0 0.0 Resistant to 5.0 105 38.0 57.1 2.9 2.0 Resistant to 10.0 225 20.0 50.2 19.6 10.2 TOTAL 523 49.5 36.7 9.0 4.8 Rifabutin in vitro MIC 99 values of ≤0.5 µg/mL, determined by the agar dilution method, for M. kansasii, M. gordonae and M. marinum have been reported; however, the clinical significance of these results is unknown.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Tuberculosis

MYCOBUTIN Capsules must not be administered for MAC prophylaxis to patients with active tuberculosis. Patients who develop complaints consistent with active tuberculosis while on prophylaxis with MYCOBUTIN should be evaluated immediately, so that those with active disease may be given an effective combination regimen of anti-tuberculosis medications. Administration of MYCOBUTIN as a single agent to patients with active tuberculosis is likely to lead to the development of tuberculosis that is resistant both to MYCOBUTIN and to rifampin.

There is no evidence that MYCOBUTIN is an effective prophylaxis against M. tuberculosis. Patients requiring prophylaxis against both M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium complex may be given isoniazid and MYCOBUTIN concurrently.

Tuberculosis in HIV-positive patients is common and may present with atypical or extrapulmonary findings. Patients are likely to have a nonreactive purified protein derivative (PPD) despite active disease. In addition to chest X-ray and sputum culture, the following studies may be useful in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the HIV-positive patient: blood culture, urine culture, or biopsy of a suspicious lymph node.

MAC Treatment with Clarithromycin

When MYCOBUTIN is used concomitantly with clarithromycin for MAC treatment, a decreased dose of MYCOBUTIN is recommended due to the increase in plasma concentrations of MYCOBUTIN (see PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions, Table 2).

Hypersensitivity and Related Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions may occur in patients receiving rifamycins. Signs and symptoms of these reactions may include hypotension, urticaria, angioedema, acute bronchospasm, conjunctivitis, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia or flu-like syndrome (weakness, fatigue, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, fever, chills, aches, rash, itching, sweats, dizziness, shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, syncope, palpitations). There have been reports of anaphylaxis with the use of rifamycins.

Monitor patients receiving MYCOBUTIN therapy for signs and/or symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions. If these symptoms occur, administer supportive measures and discontinue MYCOBUTIN.

Uveitis

Due to the possible occurrence of uveitis, patients should also be carefully monitored when MYCOBUTIN is given in combination with clarithromycin (or other macrolides) and/or fluconazole and related compounds (see PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions, Table 2). If uveitis is suspected, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist and, if considered necessary, treatment with MYCOBUTIN should be suspended (see also ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Clostridium difficile Associated Diarrhea

Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been reported with use of nearly all antibacterial agents, including MYCOBUTIN (rifabutin) Capsules, USP, and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis. Treatment with antibacterial agents alters the normal flora of the colon leading to overgrowth of C. difficile.

C. difficile produces toxins A and B which contribute to the development of CDAD. Hypertoxin producing strains of C. difficile cause increased morbidity and mortality, as these infections can be refractory to antimicrobial therapy and may require colectomy. CDAD must be considered in all patients who present with diarrhea following antibacterial use. Careful medical history is necessary since CDAD has been reported to occur over two months after the administration of antibacterial agents.

If CDAD is suspected or confirmed, ongoing antibacterial use not directed against C. difficile may need to be discontinued. Appropriate fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation, antibacterial treatment of C. difficile, and surgical evaluation should be instituted as clinically indicated.

Protease Inhibitor Drug Interaction

Protease inhibitors act as substrates or inhibitors of CYP3A4 mediated metabolism. Therefore, due to significant drug-drug interactions between protease inhibitors and rifabutin, their concomitant use should be based on the overall assessment of the patient and a patient-specific drug profile. The concomitant use of protease inhibitors may require at least a 50% reduction in rifabutin dose, and depending on the protease inhibitor, an adjustment of the antiviral drug dose. Increased monitoring for adverse events is recommended when using these drug combinations (see PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions). For further recommendations, please refer to current, official product monographs of the protease inhibitor or contact the specific manufacturer.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Because treatment with MYCOBUTIN Capsules may be associated with neutropenia, and more rarely thrombocytopenia, physicians should consider obtaining hematologic studies periodically in patients receiving prophylaxis with MYCOBUTIN.

Information for Patients

Patients should be advised of the signs and symptoms of both MAC and tuberculosis, and should be instructed to consult their physicians if they develop new complaints consistent with either of these diseases. In addition, since MYCOBUTIN may rarely be associated with myositis and uveitis, patients should be advised to notify their physicians if they develop signs or symptoms suggesting either of these disorders.

Urine, feces, saliva, sputum, perspiration, tears, and skin may be colored brown-orange with rifabutin and some of its metabolites. Soft contact lenses may be permanently stained. Patients to be treated with MYCOBUTIN should be made aware of these possibilities.

Diarrhea is a common problem caused by antibacterials which usually ends when the antibacterial is discontinued. Sometimes, after starting treatment with antibacterials, patients can develop watery and bloody stools (with or without stomach cramps and fever) even as late as two or more months after having taken the last dose of the antibacterial. If this occurs, patients should contact their physician as soon as possible.

Drug Interactions

Effect of Rifabutin on the Pharmacokinetics of Other Drugs

Rifabutin induces CYP3A enzymes and therefore may reduce the plasma concentrations of drugs metabolized by those enzymes. This effect may reduce the efficacy of standard doses of such drugs, which include itraconazole, clarithromycin, and saquinavir.

Effect of Other Drugs on Rifabutin Pharmacokinetics

Some drugs that inhibit CYP3A may significantly increase the plasma concentration of rifabutin. Therefore, carefully monitor for rifabutin associated adverse events in those patients also receiving CYP3A inhibitors, which include fluconazole and clarithromycin. In some cases, the dosage of MYCOBUTIN may need to be reduced when it is coadministered with CYP3A inhibitors.

Table 2 summarizes the results and magnitude of the pertinent drug interactions assessed with rifabutin. The clinical relevance of these interactions and subsequent dose modifications should be judged in light of the population studied, severity of the disease, patient's drug profile, and the likely impact on the risk/benefit ratio.

Table 2 Rifabutin Interaction Studies Coadministered drug Dosing regimen of coadministered drug Dosing regimen of rifabutin Study population (n) Effect on rifabutin Effect on coadministered drug Recommendation ↑ indicates increase; ↓ indicates decrease; ↔ indicates no significant change

QD- once daily; BID- twice daily; TID – thrice daily

ND - No Data

AUC - Area under the Concentration vs. Time Curve; C max - Maximum serum concentration- * compared to rifabutin 300 mg QD alone

- † compared to historical control (fosamprenavir/ritonavir 700/100 mg BID)

- ‡ also taking zidovudine 500 mg QD

- § compared to rifabutin 150 mg QD alone

- ¶ compared to rifabutin 300 mg QD alone

- # data from a case report

- Þ compared to voriconazole 200 mg BID alone

ANTIVIRALS Amprenavir 1200 mg BID × 10 days 300 mg QD × 10 days Healthy male subjects (6) ↑ AUC by 193%,

↑ Cmax by 119%↔ Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 50%. Monitor closely for adverse reactions. Delavirdine 400 mg TID 300 mg QD HIV-infected patients (7) ↑ AUC by 230%,

↑ Cmax by 128%↓ AUC by 80%,

↓ Cmax by 75%,

↓ Cmin by 17%CONTRAINDICATED Didanosine 167 or 250 mg BID × 12 days 300 or 600 mg QD × 1 HIV-infected patients (11) ↔ ↔ Fosamprenavir/ ritonavir 700 mg BID plus ritonavir 100 mg BID × 2 weeks 150 mg every other day × 2 weeks Healthy subjects (15) ↔ AUC *

↓ Cmax by 15%↑ AUC by 35% †,

↑ Cmax by 36%,

↑ Cmin by 36%,Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 75% (to a maximum 150 mg every other day or three times per week) when given with fosamprenavir/ritonavir combination. Indinavir 800 mg TID × 10 days 300 mg QD × 10 days Healthy subjects (10) ↑ AUC by 173%,

↑ Cmax by 134%↓ AUC by 34%,

↓ Cmax by 25%,

↓ Cmin by 39%Reduce rifabutin dose by 50%, and increase indinavir dose from 800 mg to 1000 mg TID. Lopinavir/ ritonavir 400/100 mg BID × 20 days 150 mg QD × 10 days Healthy subjects (14) ↑ AUC by 203% ‡

↓ Cmax by 112%↔ Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 75% (to a maximum 150 mg every other day or three times per week) when given with lopinavir/ritonavir combination. Monitor closely for adverse reactions. Reduce rifabutin dosage further, as needed. Saquinavir/ ritonavir 1000/100 mg BID × 14 or 22 days 150 mg every 3 days × 21–22 days Healthy subjects ↑ AUC by 53% §

↑ Cmax by 88%

(n=11)↓ AUC by 13%,

↓ Cmax by 15%,

(n=19)Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 75% (to a maximum 150 mg every other day or three times per week) when given with saquinavir/ritonavir combination. Monitor closely for adverse reactions. Ritonavir 500mg BID × 10 days 150 mg QD × 16 days Healthy subjects (5) ↑ AUC by 300%,

↑ Cmax by 150%ND Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 75% (to a maximum 150 mg every other day or three times per week) when given with lopinavir/ritonavir combination. Monitor closely for adverse reactions.

Reduce rifabutin dosage further, as needed.Tipranavir/ ritonavir 500/200 BID × 15 doses 150 mg single dose Healthy subjects (20) ↑ AUC by 190%,

↑ Cmax by 70%↔ Reduce rifabutin dose by at least 75% (to a maximum 150 mg every other day or three times per week) when given with tipranavir/ritonavir combination. Monitor closely for adverse reactions. Reduce rifabutin dosage further, as needed. Nelfinavir 1250 mg BID × 7–8 days 150 mg QD × 8 days HIV-infected patients (11) ↑ AUC by 83%, ¶

↑ Cmax by 19%↔ Reduce rifabutin dose by 50% (to 150 mg QD) and increase the nelfinavir dose to 1250 mg BID Zidovudine 100 or 200 mg q4h 300 or 450 mg QD HIV-infected patients (16) ↔ ↓ AUC by 32%,

↓ Cmax by 48%,Because zidovudine levels remained within the therapeutic range during coadministration of rifabutin, dosage adjustments are not necessary. ANTIFUNGALS Fluconazole 200 mg QD × 2 weeks 300 mg QD × 2 weeks HIV-infected patients (12) ↑ AUC by 82%,

↑ Cmax by 88%↔ Monitor for rifabutin associated adverse events. Reduce rifabutin dose or suspend MYCOBUTIN use if toxicity is suspected. Posaconazole 200 mg QD × 10 days 300 mg QD × 17 days Healthy subjects (8) ↑ AUC by 72%,

↑ Cmax by 31%↓ AUC by 49%,

↓ Cmax by 43%If co-administration of these two drugs cannot be avoided, patients should be monitored for adverse events associated with rifabutin administration, and lack of posaconazole efficacy. Itraconazole 200 mg QD 300 mg QD HIV-Infected patients (6) ↑ # ↓ AUC by 70%,

↓ Cmax by 75%,If co-administration of these two drugs cannot be avoided, patients should be monitored for adverse events associated with rifabutin administration, and lack of itraconazole efficacy. In a separate study, one case of uveitis was associated with increased serum rifabutin levels following co-administration of rifabutin (300 mg QD) with itraconazole (600–900 mg QD). Voriconazole 400 mg BID × 7 days (maintenance dose) 300 mg QD × 7 days Healthy male subjects (12) ↑ AUC by 331%,

↑ Cmax by 195%↑ AUC by ~100%,

↑ Cmax by ~100% ÞCONTRAINDICATED ANTI-PCP (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) Dapsone 50 mg QD 300 mg QD HIV-infected patients (16) ND ↓ AUC by 27 –40% Sulfamethoxazole- Trimethoprim 800/160 mg 300 mg QD HIV-infected patients (12) ↔ ↓ AUC by 15–20% ANTI-MAC (Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex) Azithromycin 500 mg QD × 1 day, then 250 mg QD × 9 days 300 mg QD Healthy subjects (6) ↔ ↔ Clarithromycin 500 mg BID 300 mg QD HIV-infected patients (12) ↑ AUC by 75% ↓ AUC by 50% Monitor for rifabutin associated adverse events. Reduce dose or suspend use of MYCOBUTIN if toxicity is suspected. Alternative treatment for clarithromycin should be considered when treating patients receiving rifabutin ANTI-TB (Tuberculosis) Ethambutol 1200 mg 300 mg QD × 7 days Healthy subjects (10) ND ↔ Isoniazid 300 mg 300 mg QD × 7 days Healthy subjects (6) ND ↔ OTHER Methadone 20 – 100 mg QD 300 mg QD × 13 days HIV-infected patients (24) ND ↔ Ethinylestradiol (EE)/Norethindrone (NE) 35 mg EE / 1 mg NE × 21 days 300 mg QD × 10 days Healthy female subjects (22) ND EE: ↓ AUC by

35%, ↓ C max by 20%

NE: ↓ AUC by 46%Patients should be advised to use additional or alternative methods of contraception. Theophylline 5 mg/kg 300 mg × 14 days Healthy subjects (11) ND ↔ Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Long-term carcinogenicity studies were conducted with rifabutin in mice and in rats. Rifabutin was not carcinogenic in mice at doses up to 180 mg/kg/day, or approximately 36 times the recommended human daily dose. Rifabutin was not carcinogenic in the rat at doses up to 60 mg/kg/day, about 12 times the recommended human dose.

Rifabutin was not mutagenic in the bacterial mutation assay (Ames Test) using both rifabutin-susceptible and resistant strains. Rifabutin was not mutagenic in Schizosaccharomyces pombe P 1 and was not genotoxic in V-79 Chinese hamster cells, human lymphocytes in vitro, or mouse bone marrow cells in vivo.

Fertility was impaired in male rats given 160 mg/kg (32 times the recommended human daily dose).

Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category B

Rifabutin should be used in pregnant women only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Reproduction studies have been carried out in rats and rabbits given rifabutin using dose levels up to 200 mg/kg (about 6 to 13 times the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons). No teratogenicity was observed in either species. In rats, given 200 mg/kg/day, (about 6 times the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons), there was a decrease in fetal viability. In rats, at 40 mg/kg/day (approximately equivalent to the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons), rifabutin caused an increase in fetal skeletal variants. In rabbits, at 80 mg/kg/day (about 5 times the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons), rifabutin caused maternotoxicity and increase in fetal skeletal anomalies. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, rifabutin should be used in pregnant women only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether rifabutin is excreted in human milk. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk and because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness of rifabutin for prophylaxis of MAC in children have not been established. Limited safety data are available from treatment use in 22 HIV-positive children with MAC who received MYCOBUTIN in combination with at least two other antimycobacterials for periods from 1 to 183 weeks. Mean doses (mg/kg) for these children were: 18.5 (range 15.0 to 25.0) for infants 1 year of age, 8.6 (range 4.4 to 18.8) for children 2 to 10 years of age, and 4.0 (range 2.8 to 5.4) for adolescents 14 to 16 years of age. There is no evidence that doses greater than 5 mg/kg daily are useful. Adverse experiences were similar to those observed in the adult population, and included leukopenia, neutropenia, and rash. In addition, corneal deposits have been observed in some patients during routine ophthalmologic surveillance of HIV-positive pediatric patients receiving MYCOBUTIN as part of a multiple-drug regimen for MAC prophylaxis. These are tiny, almost transparent, asymptomatic peripheral and central corneal deposits which do not impair vision. Doses of MYCOBUTIN may be administered mixed with foods such as applesauce.

Geriatric Use

Clinical studies of MYCOBUTIN did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Adverse Reactions from Clinical Trials

MYCOBUTIN Capsules were generally well tolerated in the controlled clinical trials. Discontinuation of therapy due to an adverse event was required in 16% of patients receiving MYCOBUTIN, compared to 8% of patients receiving placebo in these trials. Primary reasons for discontinuation of MYCOBUTIN were rash (4% of treated patients), gastrointestinal intolerance (3%), and neutropenia (2%).

The following table enumerates adverse experiences that occurred at a frequency of 1% or greater, among the patients treated with MYCOBUTIN in studies 023 and 027.

Table: 3 Clinical Adverse Experiences Reported in ≥1% of Patients Treated With MYCOBUTIN Adverse event MYCOBUTIN

(n = 566) %Placebo

(n = 580) %Body as a whole Abdominal pain 4 3 Asthenia 1 1 Chest pain 1 1 Fever 2 1 Headache 3 5 Pain 1 2 Blood and lymphatic system Leucopenia 10 7 Anemia 1 2 Digestive System Anorexia 2 2 Diarrhea 3 3 Dyspepsia 3 1 Eructation 3 1 Flatulence 2 1 Nausea 6 5 Nausea and vomiting 3 2 Vomiting 1 1 Musculoskeletal system Myalgia 2 1 Nervous system Insomnia 1 1 Skin and appendages Rash 11 8 Special senses Taste perversion 3 1 Urogenital system Discolored urine 30 6 CLINICAL ADVERSE EVENTS REPORTED IN <1% OF PATIENTS WHO RECEIVED MYCOBUTIN

Considering data from the 023 and 027 pivotal trials, and from other clinical studies, MYCOBUTIN appears to be a likely cause of the following adverse events which occurred in less than 1% of treated patients: flu-like syndrome, hepatitis, hemolysis, arthralgia, myositis, chest pressure or pain with dyspnea, skin discoloration, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia and jaundice.

The following adverse events have occurred in more than one patient receiving MYCOBUTIN, but an etiologic role has not been established: seizure, paresthesia, aphasia, confusion, and non-specific T wave changes on electrocardiogram.

When MYCOBUTIN was administered at doses from 1050 mg/day to 2400 mg/day, generalized arthralgia and uveitis were reported. These adverse experiences abated when MYCOBUTIN was discontinued.

Mild to severe, reversible uveitis has been reported less frequently when MYCOBUTIN is used at 300 mg as monotherapy in MAC prophylaxis versus MYCOBUTIN in combination with clarithromycin for MAC treatment (see also WARNINGS).

Uveitis has been infrequently reported when MYCOBUTIN is used at 300 mg/day as montherapy in MAC prophylaxis of HIV-infected persons, even with the concomitant use of fluconazole and/or macrolide antibacterials. However, if higher doses of MYCOBUTIN are administered in combination with these agents, the incidence of uveitis is higher. FDA proposes moving this paragraph from below with some revisions.

Patients who developed uveitis had mild to severe symptoms that resolved after treatment with corticosteroids and/or mydriatic eye drops; in some severe cases, however, resolution of symptoms occurred after several weeks.

When uveitis occurs, temporary discontinuance of MYCOBUTIN and ophthalmologic evaluation are recommended. In most mild cases, MYCOBUTIN may be restarted; however, if signs or symptoms recur, use of MYCOBUTIN should be discontinued (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, September 9, 1994).

Corneal deposits have been reported during routine ophthalmologic surveillance of some HIV-positive pediatric patients receiving MYCOBUTIN as part of a multiple drug regimen for MAC prophylaxis. The deposits are tiny, almost transparent, asymptomatic peripheral and central corneal deposits, and do not impair vision.

The following table enumerates the changes in laboratory values that were considered as laboratory abnormalities in Studies 023 and 027.

Table 4 Percentage of Patients With Laboratory Abnormalities Laboratory abnormalities MYCOBUTIN

(n = 566) %PLACEBO

(n = 580) %Includes grades 3 or 4 toxicities as specified: - * All values >450 U/L

- † All values >150 U/L

- ‡ All hemoglobin values <8.0 g/dL

- § All WBC values <1,500/mm 3

- ¶ All ANC values <750/mm 3

- # All platelet count values <50,000/mm 3

Chemistry Increased alkaline phosphatase * <1 3 Increased SGOT † 7 12 Increased SGPT † 9 11 Hematology Anemia ‡ 6 7 Eosinophilia 1 1 Leukopenia § 17 16 Neutropenia ¶ 25 20 Thrombocytopenia # 5 4 The incidence of neutropenia in patients treated with MYCOBUTIN was significantly greater than in patients treated with placebo (p = 0.03). Although thrombocytopenia was not significantly more common among patients treated with MYCOBUTIN in these trials, MYCOBUTIN has been clearly linked to thrombocytopenia in rare cases. One patient in Study 023 developed thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, which was attributed to MYCOBUTIN.

Adverse Reactions from Post-Marketing Experience

Adverse reactions identified through post-marketing surveillance by system organ class (SOC) are listed below:

Blood and lymphatic system disorders: White blood cell disorders (including agranulocytosis, lymphopenia, granulocytopenia, neutropenia, white blood cell count decreased, neutrophil count decreased), platelet count decreased.

Immune system disorders: Hypersensitivity, bronchospasm, rash, and eosinophilia.

Gastrointestinal disorders: Clostridium difficile colitis/ Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea.

Pyrexia, rash and other hypersensitivity reactions such as eosinophilia and bronchospasm might occur, as has been seen with other antibacterials.

A limited number of skin discoloration have been reported.

-

ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY

Liver abnormalities (increased bilirubin and liver weight) occurred in mice, rats and monkeys at doses (respectively) 0.5, 1 and 3-times the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons). Testicular atrophy occurred in baboons at doses 2 times the recommended human dose based on body surface area comparisons, and in rats at doses 6 times the recommended human daily dose based on body surface area comparisons.

-

OVERDOSAGE

No information is available on accidental overdosage in humans.

Treatment

While there is no experience in the treatment of overdose with MYCOBUTIN Capsules, clinical experience with rifamycins suggests that gastric lavage to evacuate gastric contents (within a few hours of overdose), followed by instillation of an activated charcoal slurry into the stomach, may help absorb any remaining drug from the gastrointestinal tract.

Rifabutin is 85% protein bound and distributed extensively into tissues (Vss:8 to 9 L/kg). It is not primarily excreted via the urinary route (less than 10% as unchanged drug); therefore, neither hemodialysis nor forced diuresis is expected to enhance the systemic elimination of unchanged rifabutin from the body in a patient with an overdose of MYCOBUTIN.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

It is recommended that MYCOBUTIN Capsules be administered at a dose of 300 mg once daily. For those patients with propensity to nausea, vomiting, or other gastrointestinal upset, administration of MYCOBUTIN at doses of 150 mg twice daily taken with food may be useful.

For patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min), consider reducing the dose of MYCOBUTIN by 50%, if toxicity is suspected. No dosage adjustment is required for patients with mild to moderate renal impairment. Reduction of the dose of MYCOBUTIN may also be needed for patients receiving concomitant treatment with certain other drugs (see PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions).

Mild hepatic impairment does not require a dose modification. The pharmacokinetics of rifabutin in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment is not known.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

MYCOBUTIN (rifabutin) Capsules, USP, are supplied as hard-gelatin capsules having an opaque red-brown cap and body, imprinted with MYCOBUTIN/PHARMACIA & UPJOHN in white ink, each containing 150 mg of rifabutin, USP.

MYCOBUTIN is available as follows:

NDC: 0013-5301-17 Bottles of 100 capsules

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

- Package Labeling:

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

MYCOBUTIN

rifabutin capsuleProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 55695-010(NDC:0013-5301) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength RIFABUTIN (UNII: 1W306TDA6S) (RIFABUTIN - UNII:1W306TDA6S) RIFABUTIN 150 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) FERRIC OXIDE RED (UNII: 1K09F3G675) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) SODIUM LAURYL SULFATE (UNII: 368GB5141J) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color red (red-brown) Score no score Shape CAPSULE Size 21mm Flavor Imprint Code MYCOBUTIN;PHARMACIA;UPJOHN Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 55695-010-00 100 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA NDA050689 12/23/1992 Labeler - Department of State Health Services, Pharmacy Branch (781992540)

Trademark Results [Mycobutin]

Mark Image Registration | Serial | Company Trademark Application Date |

|---|---|

MYCOBUTIN 74201109 1776997 Live/Registered |

PHARMACIA & UPJOHN COMPANY 1991-09-06 |

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.