Atenolol by Aurolife Pharma LLC ATENOLOL tablet

Atenolol by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Atenolol by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Aurolife Pharma LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

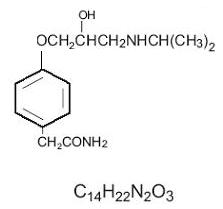

DESCRIPTION

Atenolol, a synthetic, beta1-selective (cardioselective) adrenoreceptor blocking agent, may be chemically described as benzeneacetamide, 4 -[2'-hydroxy-3'-[(1- methylethyl) amino] propoxy]-. The structural and molecular formulas are:

Atenolol (free base) has a molecular weight of 266.34. It is a relatively polar hydrophilic compound with a water solubility of 26.5 mg/mL at 37°C and a log partition coefficient (octanol/water) of 0.23. It is freely soluble in 1N HCl (300 mg/mL at 25°C) and less soluble in chloroform (3 mg/mL at 25°C).

Atenolol is available as 25, 50 and 100 mg tablets for oral administration.

Inactive Ingredients: sodium starch glycolate, crospovidone, povidone, silicified microcrystalline cellulose, magnesium stearate. -

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Atenolol is a beta1-selective (cardioselective) beta-adrenergic receptor blocking agent without membrane stabilizing or intrinsic sympathomimetic (partial agonist) activities. This preferential effect is not absolute, however, and at higher doses, atenolol inhibits beta2-adrenoreceptors, chiefly located in the bronchial and vascular musculature.Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

In man, absorption of an oral dose is rapid and consistent but incomplete. Approximately 50% of an oral dose is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, the remainder being excreted unchanged in the feces. Peak blood levels are reached between two (2) and four (4) hours after ingestion. Unlike propranolol or metoprolol, but like nadolol, atenolol undergoes little or no metabolism by the liver, and the absorbed portion is eliminated primarily by renal excretion. Over 85% of an intravenous dose is excreted in urine within 24 hours compared with approximately 50% for an oral dose. Atenolol also differs from propranolol in that only a small amount (6% to 16%) is bound to proteins in the plasma. This kinetic profile results in relatively consistent plasma drug levels with about a fourfold interpatient variation.

The elimination half-life of oral atenolol is approximately 6 to 7 hours, and there is no alteration of the kinetic profile of the drug by chronic administration. Following intravenous administration, peak plasma levels are reached within 5 minutes. Declines from peak levels are rapid (5- to 10-fold) during the first 7 hours; thereafter, plasma levels decay with a half-life similar to that of orally administered drug. Following oral doses of 50 mg or 100 mg, both beta-blocking and antihypertensive effects persist for at least 24 hours. When renal function is impaired, elimination of atenolol is closely related to the glomerular filtration rate; significant accumulation occurs when the creatinine clearance falls below 35 mL/min/1.73 m2. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)Pharmacodynamics

In standard animal or human pharmacological tests, beta-adrenoreceptor blocking activity of atenolol has been demonstrated by: (1) reduction in resting and exercise heart rate and cardiac output, (2) reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure at rest and on exercise, (3) inhibition of isoproterenol induced tachycardia, and (4) reduction in reflex orthostatic tachycardia.

A significant beta-blocking effect of atenolol, as measured by reduction of exercise tachycardia, is apparent within one hour following oral administration of a single dose. This effect is maximal at about 2 to 4 hours, and persists for at least 24 hours. Maximum reduction in exercise tachycardia occurs within 5 minutes of an intravenous dose. For both orally and intravenously administered drug, the duration of action is dose related and also bears a linear relationship to the logarithm of plasma atenolol concentration. The effect on exercise tachycardia of a single 10 mg intravenous dose is largely dissipated by 12 hours, whereas beta-blocking activity of single oral doses of 50 mg and 100 mg is still evident beyond 24 hours following administration. However, as has been shown for all beta-blocking agents, the antihypertensive effect does not appear to be related to plasma level.

In normal subjects, the beta1 selectivity of atenolol has been shown by its reduced ability to reverse the beta2-mediated vasodilating effect of isoproterenol as compared to equivalent beta-blocking doses of propranolol. In asthmatic patients, a dose of atenolol producing a greater effect on resting heart rate than propranolol resulted in much less increase in airway resistance. In a placebo controlled comparison of approximately equipotent oral doses of several beta-blockers, atenolol produced a significantly smaller decrease of FEV1 than nonselective beta-blockers such as propranolol and, unlike those agents, did not inhibit bronchodilation in response to isoproterenol.

Consistent with its negative chronotropic effect due to beta-blockade of the SA node, atenolol increases sinus cycle length and sinus node recovery time. Conduction in the AV node is also prolonged. Atenolol is devoid of membrane stabilizing activity, and increasing the dose well beyond that producing beta-blockade does not further depress myocardial contractility. Several studies have demonstrated a moderate (approximately 10%) increase in stroke volume at rest and during exercise.

In controlled clinical trials, atenolol, given as a single daily oral dose, was an effective antihypertensive agent providing 24-hour reduction of blood pressure. Atenolol has been studied in combination with thiazide-type diuretics, and the blood pressure effects of the combination are approximately additive. Atenolol is also compatible with methyldopa, hydralazine, and prazosin, each combination resulting in a larger fall in blood pressure than with the single agents. The dose range of atenolol is narrow and increasing the dose beyond 100 mg once daily is not associated with increased antihypertensive effect. The mechanisms of the antihypertensive effects of beta-blocking agents have not been established. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed and include: (1) competitive antagonism of catecholamines at peripheral (especially cardiac) adrenergic neuron sites, leading to decreased cardiac output, (2) a central effect leading to reduced sympathetic outflow to the periphery, and (3) suppression of renin activity. The results from long-term studies have not shown any diminution of the antihypertensive efficacy of atenolol with prolonged use.

By blocking the positive chronotropic and inotropic effects of catecholamines and by decreasing blood pressure, atenolol generally reduces the oxygen requirements of the heart at any given level of effort, making it useful for many patients in the long-term management of angina pectoris. On the other hand, atenolol can increase oxygen requirements by increasing left ventricular fiber length and end diastolic pressure, particularly in patients with heart failure.

In a multicenter clinical trial (ISIS-1) conducted in 16,027 patients with suspected myocardial infarction, patients presenting within 12 hours (mean = 5 hours) after the onset of pain were randomized to either conventional therapy plus atenolol (n = 8,037), or conventional therapy alone (n = 7,990). Patients with a heart rate of < 50 bpm or systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg, or with other contraindications to beta-blockade were excluded. Thirty-eight percent of each group were treated within 4 hours of onset of pain. The mean time from onset of pain to entry was 5 ± 2.7 hours in both groups. Patients in the atenolol group were to receive atenolol I.V. injection 5 to 10 mg given over 5 minutes plus atenolol tablets 50 mg every 12 hours orally on the first study day (the first oral dose administered about 15 minutes after the IV dose) followed by either atenolol tablets 100 mg once daily or atenolol tablets 50 mg twice daily on days 2 to 7. The groups were similar in demographic and medical history characteristics and in electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial infarction, bundle branch block, and first degree atrioventricular block at entry.

During the treatment period (days 0 to 7), the vascular mortality rates were 3.89% in the atenolol group (313 deaths) and 4.57% in the control group (365 deaths). This absolute difference in rates, 0.68%, is statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level. The absolute difference translates into a proportional reduction of 15% (3.89-4.57/4.57 = -0.15). The 95% confidence limits are 1% to 27%. Most of the difference was attributed to mortality in days 0 to 1 (atenolol – 121 deaths; control - 171 deaths).

Despite the large size of the ISIS-1 trial, it is not possible to identify clearly subgroups of patients most likely or least likely to benefit from early treatment with atenolol. Good clinical judgment suggests, however, that patients who are dependent on sympathetic stimulation for maintenance of adequate cardiac output and blood pressure are not good candidates for beta-blockade. Indeed, the trial protocol reflected that judgment by excluding patients with blood pressure consistently below 100 mmHg systolic. The overall results of the study are compatible with the possibility that patients with borderline blood pressure (less than 120 mmHg systolic), especially if over 60 years of age, are less likely to benefit.

The mechanism through which atenolol improves survival in patients with definite or suspected acute myocardial infarction is unknown, as is the case for other beta-blockers in the postinfarction setting. Atenolol, in addition to its effects on survival, has shown other clinical benefits including reduced frequency of ventricular premature beats, reduced chest pain, and reduced enzyme elevation.Atenolol Geriatric Pharmacology

In general, elderly patients present higher atenolol plasma levels with total clearance values about 50% lower than younger subjects. The half-life is markedly longer in the elderly compared to younger subjects. The reduction in atenolol clearance follows the general trend that the elimination of renally excreted drugs is decreased with increasing age. -

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Hypertension

Atenolol tablets are indicated in the management of hypertension. They may be used alone or concomitantly with other antihypertensive agents, particularly with a thiazide-type diuretic.Angina Pectoris Due to Coronary Atherosclerosis

Atenolol tablets are indicated for the long-term management of patients with angina pectoris.Acute Myocardial Infarction

Atenolol tablets are indicated in the management of hemodynamically stable patients with definite or suspected acute myocardial infarction to reduce cardiovascular mortality. Treatment can be initiated as soon as the patient’s clinical condition allows. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, CONTRAINDICATIONS, and WARNINGS.) In general, there is no basis for treating patients like those who were excluded from the ISIS-1 trial (blood pressure less than 100 mmHg systolic, heart rate less than 50 bpm) or have other reasons to avoid beta-blockade. As noted above, some subgroups (e.g., elderly patients with systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg) seemed less likely to benefit. -

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Atenolol tablets are contraindicated in sinus bradycardia, heart block greater than first degree, cardiogenic shock, and overt cardiac failure. (See WARNINGS.)

Atenolol tablets are contraindicated in those patients with a history of hypersensitivity to the atenolol or any of the drug product’s components. -

WARNINGS

Cardiac Failure

Sympathetic stimulation is necessary in supporting circulatory function in congestive heart failure, and beta-blockade carries the potential hazard of further depressing myocardial contractility and precipitating more severe failure.

In patients with acute myocardial infarction, cardiac failure which is not promptly and effectively controlled by 80 mg of intravenous furosemide or equivalent therapy is a contraindication to beta-blocker treatment.In Patients Without a History of Cardiac Failure

Continued depression of the myocardium with beta-blocking agents over a period of time can, in some cases, lead to cardiac failure. At the first sign or symptom of impending cardiac failure, patients should be treated appropriately according to currently recommended guidelines, and the response observed closely. If cardiac failure continues despite adequate treatment, atenolol should be withdrawn. (See DOSAGE AND ADMNISTRATION)Cessation of Therapy with Atenolol

Patients with coronary artery disease, who are being treated with atenolol, should be advised against abrupt discontinuation of therapy. Severe exacerbation of angina and the occurrence of myocardial infarction and ventricular arrhythmias have been reported in angina patients following the abrupt discontinuation of therapy with beta-blockers. The last two complications may occur with or without preceding exacerbation of the angina pectoris. As with other beta-blockers, when discontinuation of atenolol is planned, the patients should be carefully observed and advised to limit physical activity to a minimum. If the angina worsens or acute coronary insufficiency develops, it is recommended that atenolol be promptly reinstituted, at least temporarily. Because coronary artery disease is common and may be unrecognized, it may be prudent not to discontinue atenolol therapy abruptly even in patients treated only for hypertension. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)Concomitant Use of Calcium Channel Blockers

Bradycardia and heart block can occur and the left ventricular end diastolic pressure can rise when beta-blockers are administered with verapamil or diltiazem. Patients with preexisting conduction abnormalities or left ventricular dysfunction are particularly susceptible. (See PRECAUTIONS.)Bronchospastic Diseases

PATIENTS WITH BRONCHOSPASTIC DISEASE SHOULD, IN GENERAL, NOT RECEIVE BETA-BLOCKERS. Because of its relative beta1 selectivity, however, atenolol may be used with caution in patients with bronchospastic disease who do not respond to, or cannot tolerate, other antihypertensive treatment. Since beta1 selectivity is not absolute, the lowest possible dose of atenolol should be used with therapy initiated at 50 mg and a beta2-stimulating agent (bronchodilator) should be made available. If dosage must be increased, dividing the dose should be considered in order to achieve lower peak blood levels.

Anesthesia and Major Surgery

It is not advisable to withdraw beta-adrenoreceptor blocking drugs prior to surgery in the majority of patients. However, care should be taken when using anesthetic agents such as those which may depress the myocardium. Vagal dominance, if it occurs, may be corrected with atropine (1 to 2 mg IV).

Atenolol, like other beta-blockers, is a competitive inhibitor of beta-receptor agonists and its effects on the heart can be reversed by administration of such agents: e.g., dobutamine or isoproterenol with caution (see section on OVERDOSAGE).Diabetes and Hypoglycemia

Atenolol should be used with caution in diabetic patients if a beta-blocking agent is required. Beta-blockers may mask tachycardia occurring with hypoglycemia, but other manifestations such as dizziness and sweating may not be significantly affected. At recommended doses atenolol does not potentiate insulin-induced hypoglycemia and, unlike nonselective beta-blockers, does not delay recovery of blood glucose to normal levels.

Thyrotoxicosis

Beta-adrenergic blockade may mask certain clinical signs (e.g., tachycardia) of hyperthyroidism. Abrupt withdrawal of beta-blockade might precipitate a thyroid storm; therefore, patients suspected of developing thyrotoxicosis from whom atenolol therapy is to be withdrawn should be monitored closely. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)Pregnancy and Fetal Injury

Atenolol can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Atenolol crosses the placental barrier and appears in cord blood. Administration of atenolol, starting in the second trimester of pregnancy, has been associated with the birth of infants that are small for gestational age. No studies have been performed on the use of atenolol in the first trimester and the possibility of fetal injury cannot be excluded. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.

Neonates born to mothers who are receiving atenolol at parturition or breastfeeding may be at risk for hypoglycemia and bradycardia. Caution should be exercised when atenolol is administered during pregnancy or to a woman who is breastfeeding. (See PRECAUTIONS, Nursing Mothers.)

Atenolol has been shown to produce a dose-related increase in embryo/fetal resorptions in rats at doses equal to or greater than 50 mg/kg/day or 25 or more times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose.* Although similar effects were not seen in rabbits, the compound was not evaluated in rabbits at doses above 25 mg/kg/day or 12.5 times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose.*

*Based on the maximum dose of 100 mg/day in a 50 kg patient. -

PRECAUTIONS

General

Patients already on a beta-blocker must be evaluated carefully before atenolol is administered. Initial and subsequent atenolol dosages can be adjusted downward depending on clinical observations including pulse and blood pressure. Atenolol may aggravate peripheral arterial circulatory disorders.

Impaired Renal Function

The drug should be used with caution in patients with impaired renal function. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)Drug Interactions

Catecholamine-depleting drugs (e.g., reserpine) may have an additive effect when given with beta-blocking agents. Patients treated with atenolol plus a catecholamine depletor should therefore be closely observed for evidence of hypotension and/or marked bradycardia which may produce vertigo, syncope, or postural hypotension.

Calcium channel blockers may also have an additive effect when given with atenolol (See WARNINGS).

Disopyramide is a Type I antiarrhythmic drug with potent negative inotropic and chronotropic effects. Disopyramide has been associated with severe bradycardia, asystole and heart failure when administered with beta-blockers.

Amiodarone is an antiarrhythmic agent with negative chronotropic properties that may be additive to those seen with beta-blockers.

Beta-blockers may exacerbate the rebound hypertension which can follow the withdrawal of clonidine. If the two drugs are coadministered, the beta-blocker should be withdrawn several days before the gradual withdrawal of clonidine. If replacing clonidine by beta-blocker therapy, the introduction of beta-blockers should be delayed for several days after clonidine administration has stopped.

Concomitant use of prostaglandin synthase inhibiting drugs, e.g., indomethacin, may decrease the hypotensive effects of beta-blockers.

Information on concurrent usage of atenolol and aspirin is limited. Data from several studies, i.e., TIMI-II, ISIS-2, currently do not suggest any clinical interaction between aspirin and beta-blockers in the acute myocardial infarction setting.

While taking beta-blockers, patients with a history of anaphylactic reaction to a variety of allergens may have a more severe reaction on repeated challenge, either accidental, diagnostic or therapeutic. Such patients may be unresponsive to the usual doses of epinephrine used to treat the allergic reaction.

Both digitalis glycosides and beta-blockers slow atrioventricular conduction and decrease heart rate. Concomitant use can increase the risk of bradycardia.Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Two long-term (maximum dosing duration of 18 or 24 months) rat studies and one long-term (maximum dosing duration of 18 months) mouse study, each employing dose levels as high as 300 mg/kg/day or 150 times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose,* did not indicate a carcinogenic potential of atenolol. A third (24 month) rat study, employing doses of 500 and 1,500 mg/kg/day (250 and 750 times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose*) resulted in increased incidences of benign adrenal medullary tumors in males and females, mammary fibroadenomas in females, and anterior pituitary adenomas and thyroid parafollicular cell carcinomas in males. No evidence of a mutagenic potential of atenolol was uncovered in the dominant lethal test (mouse), in vivo cytogenetics test (Chinese hamster) or Ames test (S typhimurium).

Fertility of male or female rats (evaluated at dose levels as high as 200 mg/kg/day or 100 times the maximum recommended human dose*) was unaffected by atenolol administration.Animal Toxicology

Chronic studies employing oral atenolol performed in animals have revealed the occurrence of vacuolation of epithelial cells of Brunner's glands in the duodenum of both male and female dogs at all tested dose levels of atenolol (starting at 15 mg/kg/day or 7.5 times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose*) and increased incidence of atrial degeneration of hearts of male rats at 300 but not 150 mg atenolol/kg/day (150 and 75 times the maximum recommended human antihypertensive dose,* respectively).

* Based on the maximum dose of 100 mg/day in a 50 kg patient.Nursing Mothers

Atenolol is excreted in human breast milk at a ratio of 1.5 to 6.8 when compared to the concentration in plasma. Caution should be exercised when atenolol is administered to a nursing woman. Clinically significant bradycardia has been reported in breast-fed infants. Premature infants, or infants with impaired renal function, may be more likely to develop adverse effects.

Neonates born to mothers who are receiving atenolol at parturition or breastfeeding may be at risk for hypoglycemia and bradycardia. Caution should be exercised when atenolol is administered during pregnancy or to a woman who is breastfeeding (see WARNINGS, Pregnancy and Fetal Injury).Geriatric Use

Hypertension and Angina Pectoris Due to Coronary Atherosclerosis

Clinical studies of atenolol did not include sufficient number of patients aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.Acute Myocardial Infarction

Of the 8,037 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction randomized to atenolol in the ISIS-1 trial (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY), 33% (2,644) were 65 years of age and older. It was not possible to identify significant differences in efficacy and safety between older and younger patients; however, elderly patients with systolic blood pressure < 120 mmHg seemed less likely to benefit (See INDICATIONS AND USAGE).

In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy. Evaluation of patients with hypertension or myocardial infarction should always include assessment of renal function. -

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most adverse effects have been mild and transient.

The frequency estimates in the following table were derived from controlled studies in hypertensive patients in which adverse reactions were either volunteered by the patient (U.S. studies) or elicited, e.g., by checklist (foreign studies). The reported frequency of elicited adverse effects was higher for both atenolol and placebo-treated patients than when these reactions were volunteered. Where frequency of adverse effects of atenolol and placebo is similar, causal relationship to atenolol is uncertain.

Volunteered

(U.S. Studies)

Total - Volunteered and Elicited

(Foreign+U.S. Studies)

Atenolol

(n=164)

%

Placebo

(n=206)

%

Atenolol

(n=399)

%

Placebo

(n=407)

%

CARDIOVASCULAR

Bradycardia

3

0

3

0

Cold Extremities

0

0.5

12

5

Postural Hypotension

2

1

4

5

Leg Pain

0

0.5

3

1

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM/NEUROMUSCULAR

Dizziness

4

1

13

6

Vertigo

2

0.5

2

0.2

Lightheadedness

1

0

3

0.7

Tiredness

0.6

0.5

26

13

Fatigue

3

1

6

5

Lethargy

1

0

3

0.7

Drowsiness

0.6

0

2

0.5

Depression

0.6

0.5

12

9

Dreaming

0

0

3

1

GASTROINTESTINAL

Diarrhea

2

0

3

2

Nausea

4

1

3

1

RESPIRATORY (see WARNINGS)

Wheeziness

0

0

3

3

Dyspnea

0.6

1

6

4

Acute Myocardial Infarction

In a series of investigations in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction, bradycardia and hypotension occurred more commonly, as expected for any beta-blocker, in atenolol-treated patients than in control patients. However, these usually responded to atropine and/or to withholding further dosage of atenolol. The incidence of heart failure was not increased by atenolol. Inotropic agents were infrequently used. The reported frequency of these and other events occurring during these investigations is given in the following table.

In a study of 477 patients, the following adverse events were reported during either intravenous and/or oral atenolol administration:

Conventional Therapy

Plus Atenolol

(n=244)

Conventional Therapy

Alone

(n=233)

Bradycardia

43

(18%)

24

(10%)

Hypotension

60

(25%)

34

(15%)

Bronchospasm

3

(1.2%)

2

(0.9%)

Heart Failure

46

(19%)

56

(24%)

Heart Block

11

(4.5%)

10

(4.3%)

BBB + Major

Axis Deviation

16

(6.6%)

28

(12%)

Supraventricular Tachycardia

28

(11.5%)

45

(19%)

Atrial Fibrillation

12

(5%)

29

(11%)

Atrial Flutter

4

(1.6%)

7

(3%)

Ventricular Tachycardia

39

(16%)

52

(22%)

Cardiac Reinfarction

0

(0%)

6

(2.6%)

Total Cardiac Arrests

4

(1.6%)

16

(6.9%)

Nonfatal Cardiac Arrests

4

(1.6%)

12

(5.1%)

Deaths

7

(2.9%)

16

(6.9%)

Cardiogenic Shock

1

(0.4%)

4

(1.7%)

Development of Ventricular

Septal Defect

0

(0%)

2

(0.9%)

Development of Mitral

Regurgitation

0

(0%)

2

(0.9%)

Renal Failure

1

(0.4%)

0

(0%)

Pulmonary Emboli

3

(1.2%)

0

(0%)

In the subsequent International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-1) including over 16,000 patients of whom 8,037 were randomized to receive atenolol treatment, the dosage of intravenous and subsequent oral atenolol was either discontinued or reduced for the following reasons:

*Full dosage was 10 mg and some patients received less than 10 mg but more than 5 mg.

Reasons for Reduced Dosage

IV Atenolol Reduced Dose

(< 5 mg)*

Oral Partial Dose

Hypotension/Bradycardia

105

(1.3%)

1168

(14.5%)

Cardiogenic Shock

4

(.04%)

35

(.44%)

Reinfarction

0

(0%)

5

(.06%)

Cardiac Arrest

5

(.06%)

28

(.34%)

Heart Block (> first degree)

5

(.06%)

143

(1.7%)

Cardiac Failure

1

(.01%)

233

(2.9%)

Arrhythmias

3

(.04%)

22

(.27%)

Bronchospasm

1

(.01%)

50

(.62%)

During postmarketing experience with atenolol, the following have been reported in temporal relationship to the use of the drug: elevated liver enzymes and/or bilirubin, hallucinations, headache, impotence, Peyronie's disease, postural hypotension which may be associated with syncope, psoriasiform rash or exacerbation of psoriasis, psychoses, purpura, reversible alopecia, thrombocytopenia, visual disturbance, sick sinus syndrome, and dry mouth. Atenolol, like other beta-blockers, has been associated with the development of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), lupus syndrome, and Raynaud’s phenomenon.POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS

In addition, a variety of adverse effects have been reported with other beta-adrenergic blocking agents, and may be considered potential adverse effects of atenolol.

Hematologic: Agranulocytosis.

Allergic: Fever, combined with aching and sore throat, laryngospasm, and respiratory distress.

Central Nervous System: Reversible mental depression progressing to catatonia; an acute reversible syndrome characterized by disorientation of time and place; short-term memory loss; emotional lability with slightly clouded sensorium; and, decreased performance on neuropsychometrics.

Gastrointestinal: Mesenteric arterial thrombosis, ischemic colitis.

Other: Erythematous rash.

Miscellaneous: There have been reports of skin rashes and/or dry eyes associated with the use of beta-adrenergic blocking drugs. The reported incidence is small, and in most cases, the symptoms have cleared when treatment was withdrawn. Discontinuance of the drug should be considered if any such reaction is not otherwise explicable. Patients should be closely monitored following cessation of therapy. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)

The oculomucocutaneous syndrome associated with the beta-blocker practolol has not been reported with atenolol. Furthermore, a number of patients who had previously demonstrated established practolol reactions were transferred to atenolol therapy with subsequent resolution or quiescence of the reaction. -

OVERDOSAGE

Overdosage with atenolol has been reported with patients surviving acute doses as high as 5 g. One death was reported in a man who may have taken as much as 10 g acutely.

The predominant symptoms reported following atenolol overdose are lethargy, disorder of respiratory drive, wheezing, sinus pause and bradycardia. Additionally, common effects associated with overdosage of any beta-adrenergic blocking agent and which might also be expected in atenolol overdose are congestive heart failure, hypotension, bronchospasm and/or hypoglycemia.

Treatment of overdose should be directed to the removal of any unabsorbed drug by induced emesis, gastric lavage, or administration of activated charcoal. Atenolol can be removed from the general circulation by hemodialysis. Other treatment modalities should be employed at the physician's discretion and may include:

BRADYCARDIA: Atropine intravenously. If there is no response to vagal blockade, give isoproterenol cautiously. In refractory cases, a transvenous cardiac pacemaker may be indicated.

HEART BLOCK (SECOND OR THIRD DEGREE): Isoproterenol or transvenous cardiac pacemaker.

CARDIAC FAILURE: Digitalize the patient and administer a diuretic. Glucagon has been reported to be useful.

HYPOTENSION: Vasopressors such as dopamine or norepinephrine (levarterenol). Monitor blood pressure continuously.

BRONCHOSPASM: A beta2 stimulant such as isoproterenol or terbutaline and/or aminophylline.

HYPOGLYCEMIA: Intravenous glucose.

Based on the severity of symptoms, management may require intensive support care and facilities for applying cardiac and respiratory support. -

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Hypertension

The initial dose of atenolol is 50 mg given as one tablet a day either alone or added to diuretic therapy. The full effect of this dose will usually be seen within one to two weeks. If an optimal response is not achieved, the dosage should be increased to atenolol 100 mg given as one tablet a day. Increasing the dosage beyond 100 mg a day is unlikely to produce any further benefit.

Atenolol may be used alone or concomitantly with other antihypertensive agents including thiazide-type diuretics, hydralazine, prazosin, and alpha-methyldopa.Angina Pectoris

The initial dose of atenolol is 50 mg given as one tablet a day. If an optimal response is not achieved within one week, the dosage should be increased to atenolol 100 mg given as one tablet a day. Some patients may require a dosage of 200 mg once a day for optimal effect.

Twenty-four hour control with once daily dosing is achieved by giving doses larger than necessary to achieve an immediate maximum effect. The maximum early effect on exercise tolerance occurs with doses of 50 to 100 mg, but at these doses the effect at 24 hours is attenuated, averaging about 50% to 75% of that observed with once a day oral doses of 200 mg.Acute Myocardial Infarction

In patients with definite or suspected acute myocardial infarction, treatment with atenolol I.V. injection should be initiated as soon as possible after the patient's arrival in the hospital and after eligibility is established. Such treatment should be initiated in a coronary care or similar unit immediately after the patient's hemodynamic condition has stabilized. Treatment should begin with the intravenous administration of 5 mg atenolol over 5 minutes followed by another 5 mg intravenous injection 10 minutes later. Atenolol I.V. injection should be administered under carefully controlled conditions including monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiogram. Dilutions of atenolol I.V. injection in dextrose injection USP, sodium chloride injection USP, or sodium chloride and dextrose injection may be used. These admixtures are stable for 48 hours if they are not used immediately.

In patients who tolerate the full intravenous dose (10 mg), atenolol tablets 50 mg should be initiated 10 minutes after the last intravenous dose followed by another 50 mg oral dose 12 hours later. Thereafter, atenolol can be given orally either 100 mg once daily or 50 mg twice a day for a further 6 to 9 days or until discharge from the hospital. If bradycardia or hypotension requiring treatment or any other untoward effects occur, atenolol should be discontinued. (See full prescribing information prior to initiating therapy with atenolol tablets.)

Data from other beta-blocker trials suggest that if there is any question concerning the use of IV beta-blocker or clinical estimate that there is a contraindication, the IV beta-blocker may be eliminated and patients fulfilling the safety criteria may be given atenolol tablets 50 mg twice daily or 100 mg once a day for at least seven days (if the IV dosing is excluded).

Although the demonstration of efficacy of atenolol is based entirely on data from the first seven postinfarction days, data from other beta-blocker trials suggest that treatment with beta-blockers that are effective in the postinfarction setting may be continued for one to three years if there are no contraindications.

Atenolol is an additional treatment to standard coronary care unit therapy.Elderly Patients or Patients with Renal Impairment

Atenolol is excreted by the kidneys; consequently dosage should be adjusted in cases of severe impairment of renal function. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy. Evaluation of patients with hypertension or myocardial infarction should always include assessment of renal function. Atenolol excretion would be expected to decrease with advancing age.

No significant accumulation of atenolol occurs until creatinine clearance falls below 35 mL/min/1.73 m2. Accumulation of atenolol and prolongation of its half-life were studied in subjects with creatinine clearance between 5 and 105 mL/min. Peak plasma levels were significantly increased in subjects with creatinine clearances below 30 mL/min.

The following maximum oral dosages are recommended for elderly, renally-impaired patients and for patients with renal impairment due to other causes:

Creatinine Clearance

(mL/min/1.73 m2)

Atenolol Elimination Half-Life

(h)

Maximum Dosage

15-35

16-27

50 mg daily

<15

>27

25 mg daily

Some renally-impaired or elderly patients being treated for hypertension may require a lower starting dose of atenolol: 25 mg given as one tablet a day. If this 25 mg dose is used, assessment of efficacy must be made carefully. This should include measurement of blood pressure just prior to the next dose ("trough" blood pressure) to ensure that the treatment effect is present for a full 24 hours.

Although a similar dosage reduction may be considered for elderly and/or renally-impaired patients being treated for indications other than hypertension, data are not available for these patient populations.

Patients on hemodialysis should be given 25 mg or 50 mg after each dialysis; this should be done under hospital supervision as marked falls in blood pressure can occur. -

HOW SUPPLIED

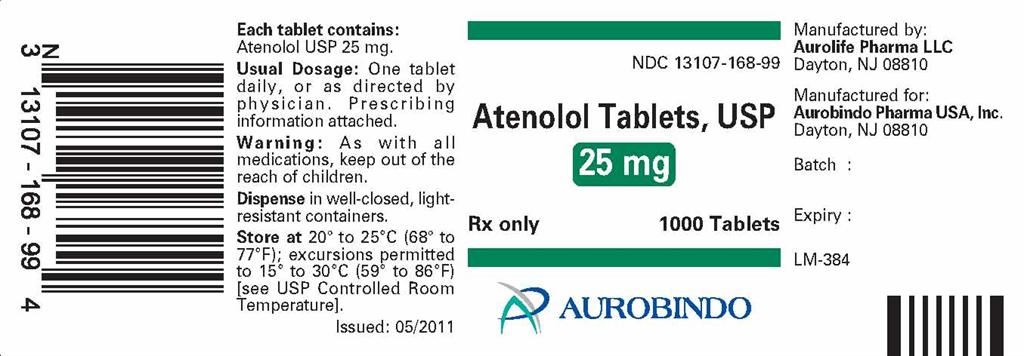

Atenolol Tablets USP, 25 mg round, flat-face, beveled-edge, white to off-white uncoated tablets with “D” debossed on one side and “21” debossed on the other side.

Bottles of 100 NDC: 13107-168-01

Bottles of 1000 NDC 13017-168-99

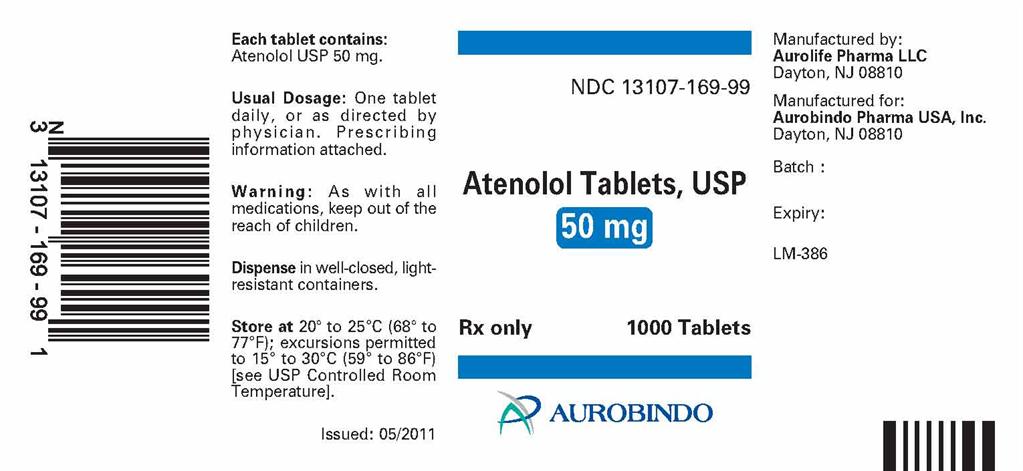

Atenolol Tablets USP, 50 mg round, flat-face, beveled-edge, white to off-white uncoated tablets with “D” debossed above the break line on one side and “22” debossed on the other side.

Bottles of 100 NDC: 13017-169-01

Bottles of 1000 NDC: 13017-169-99

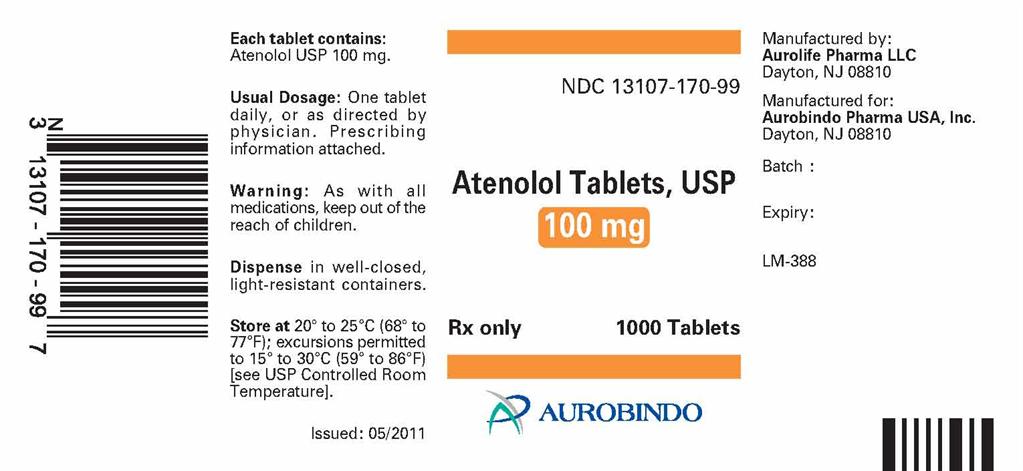

Atenolol Tablets USP, 100 mg round, flat-face, beveled-edge, white to off-white uncoated tablets with “D” debossed on one side and “23” debossed on the other side.

Bottles of 100 NDC: 13017-170-01

Bottles of 1000 NDC: 13017-170-99

Store at 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F); excursions permitted to 15° to 30°C (59° to 86°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Dispense in well-closed, light-resistant containers.

Manufactured by:

Aurolife Pharma LLC

Dayton, NJ 08810

Manufactured for:

Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc.

Dayton, NJ 08810

Issued: 09/2010 - PACKAGE LABEL-PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 25 mg (1000 Tablet Bottle)

- PACKAGE LABEL-PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 50 mg (1000 Tablet Bottle)

- PACKAGE LABEL-PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 100 mg (1000 Tablet Bottle)

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ATENOLOL

atenolol tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 13107-168 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ATENOLOL (UNII: 50VV3VW0TI) (ATENOLOL - UNII:50VV3VW0TI) ATENOLOL 25 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) CROSPOVIDONE (UNII: 68401960MK) POVIDONE K90 (UNII: RDH86HJV5Z) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (White to Off-white) Score no score Shape ROUND (Flat-face, Beveled-edge) Size 6mm Flavor Imprint Code D;21 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 13107-168-01 100 in 1 BOTTLE 2 NDC: 13107-168-99 1000 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA078512 06/20/2011 ATENOLOL

atenolol tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 13107-169 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ATENOLOL (UNII: 50VV3VW0TI) (ATENOLOL - UNII:50VV3VW0TI) ATENOLOL 50 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) CROSPOVIDONE (UNII: 68401960MK) POVIDONE K90 (UNII: RDH86HJV5Z) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (White to Off-white) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND (Flat-face, Beveled-edge) Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code D;22 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 13107-169-01 100 in 1 BOTTLE 2 NDC: 13107-169-99 1000 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA078512 06/20/2011 ATENOLOL

atenolol tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 13107-170 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ATENOLOL (UNII: 50VV3VW0TI) (ATENOLOL - UNII:50VV3VW0TI) ATENOLOL 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) CROSPOVIDONE (UNII: 68401960MK) POVIDONE K90 (UNII: RDH86HJV5Z) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (White to Off-white) Score no score Shape ROUND (Flat-face, Beveled-edge) Size 9mm Flavor Imprint Code D;23 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 13107-170-01 100 in 1 BOTTLE 2 NDC: 13107-170-99 1000 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA078512 06/20/2011 Labeler - Aurolife Pharma LLC (829084461)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.