DEPAKOTE ER- divalproex sodium tablet, extended release

Depakote by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Depakote by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by REMEDYREPACK INC.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Depakote ER safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Depakote ER.

Depakote ER (divalproex sodium) extended-release tablets, for oral use

Initial U.S. Approval: 2000WARNING: LIFE THREATENING ADVERSE REACTIONS

See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

- Hepatotoxicity, including fatalities, usually during the first 6 months of treatment. Children under the age of two years and patients with mitochondrial disorders are at higher risk. Monitor patients closely, and perform serum liver testing prior to therapy and at frequent intervals thereafter (5.1)

- Fetal Risk, particularly neural tube defects, other major malformations, and decreased IQ (5.2, 5.3, 5.4)Fetal Risk, particularly neural tube defects, other major malformations, and decreased IQ (5.2, 5.3, 5.4)

- Pancreatitis, including fatal hemorrhagic cases (5.5)

RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

Boxed Warning, Fetal Risk 2/2019 Indications and Usage, Important Limitations (1.4) 2/2019 Contraindications (4) 2/2019 Warnings and Precautions, Use in Women of Childbearing Potential (5.4) 2/2019 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Depakote ER is indicated for:

- Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder, with or without psychotic features (1.1)

- Monotherapy and adjunctive therapy of complex partial seizures and simple and complex absence seizures; adjunctive therapy in patients with multiple seizure types that include absence seizures (1.2)

- Prophylaxis of migraine headaches (1.3)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

- Depakote ER is intended for once-a-day oral administration. Depakote ER should be swallowed whole and should not be crushed or chewed (2.1, 2.2).

- Mania: Initial dose is 25 mg/kg/day, increasing as rapidly as possible to achieve therapeutic response or desired plasma level (2.1). The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day (2.1, 2.2).

- Complex Partial Seizures: Start at 10 to 15 mg/kg/day, increasing at 1 week intervals by 5 to 10 mg/kg/day to achieve optimal clinical response; if response is not satisfactory, check valproate plasma level; see full prescribing information for conversion to monotherapy (2.2). The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day (2.1, 2.2).

- Absence Seizures: Start at 15 mg/kg/day, increasing at 1 week intervals by 5 to 10 mg/kg/day until seizure control or limiting side effects (2.2). The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day (2.1, 2.2).

- Migraine: The recommended starting dose is 500 mg/day for 1 week, thereafter increasing to 1,000 mg/day (2.3).

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Tablets: 250 mg and 500 mg (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Hepatic disease or significant hepatic dysfunction (4, 5.1)

- Known mitochondrial disorders caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (POLG) (4, 5.1)

- Suspected POLG-related disorder in children under two years of age (4, 5.1)

- Known hypersensitivity to the drug (4, 5.12)

- Urea cycle disorders (4, 5.6)

- Prophylaxis of migraine headaches: Pregnant women, women of childbearing potential not using effective contraception (4, 8.1)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Hepatotoxicity; evaluate high risk populations and monitor serum liver tests (5.1)

- Birth defects, decreased IQ, and neurodevelopmental disorders following in utero exposure; should not be used to treat women with epilepsy or bipolar disorder who are pregnant or who plan to become pregnant or to treat a woman of childbearing potential unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable (5.2, 5.3, 5.4)

- Pancreatitis; Depakote ER should ordinarily be discontinued (5.5)

- Suicidal behavior or ideation; Antiepileptic drugs, including Depakote ER, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior (5.7)

- Bleeding and other hematopoietic disorders; monitor platelet counts and coagulation tests (5.8)

- Hyperammonemia and hyperammonemic encephalopathy; measure ammonia level if unexplained lethargy and vomiting or changes in mental status, and also with concomitant topiramate use; consider discontinuation of valproate therapy (5.6, 5.9, 5.10)

- Hypothermia; Hypothermia has been reported during valproate therapy with or without associated hyperammonemia. This adverse reaction can also occur in patients using concomitant topiramate (5.11)

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan hypersensitivity reaction; discontinue Depakote ER (5.12)

- Somnolence in the elderly can occur. Depakote ER dosage should be increased slowly and with regular monitoring for fluid and nutritional intake (5.14)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

- Most common adverse reactions (reported >5%) are abdominal pain, alopecia, amblyopia/blurred vision, amnesia, anorexia, asthenia, ataxia, back pain, bronchitis, constipation, depression, diarrhea, diplopia, dizziness, dyspnea, dyspepsia, ecchymosis, emotional lability, fever, flu syndrome, headache, increased appetite, infection, insomnia, nausea, nervousness, nystagmus, peripheral edema, pharyngitis, rash, rhinitis, somnolence, thinking abnormal, thrombocytopenia, tinnitus, tremor, vomiting, weight gain, weight loss (6.1, 6.2, 6.3).

- The safety and tolerability of valproate in pediatric patients were shown to be comparable to those in adults

(8.4).

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AbbVie Inc. at 1-800-633-9110 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

- Hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, primidone, rifampin) can increase valproate clearance, while enzyme inhibitors (e.g., felbamate) can decrease valproate clearance. Therefore increased monitoring of valproate and concomitant drug concentrations and dosage adjustment are indicated whenever enzyme-inducing or inhibiting drugs are introduced or withdrawn (7.1)

- Aspirin, carbapenem antibiotics, estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives: Monitoring of valproate concentrations is recommended (7.1)

- Co-administration of valproate can affect the pharmacokinetics of other drugs (e.g. diazepam, ethosuximide, lamotrigine, phenytoin) by inhibiting their metabolism or protein binding displacement (7.2)

- Patients stabilized on rufinamide should begin valproate therapy at a low dose, and titrate to clinically effective dose (7.2)

- Dosage adjustment of amitriptyline/nortriptyline, propofol, warfarin, and zidovudine may be necessary if used concomitantly with Depakote ER (7.2)

- Topiramate: Hyperammonemia and encephalopathy (5.10, 7.3)

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

- Pregnancy: Depakote ER can cause congenital malformations including neural tube defects, decreased IQ, and neurodevelopmental disorders (5.2, 5.3, 8.1)

- Pediatric: Children under the age of two years are at considerably higher risk of fatal hepatotoxicity (5.1, 8.4)

- Geriatric: Reduce starting dose; increase dosage more slowly; monitor fluid and nutritional intake, and somnolence (5.14, 8.5)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 11/2019

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNING: LIFE THREATENING ADVERSE REACTIONS

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Mania

1.2 Epilepsy

1.3 Migraine

1.4 Important Limitations

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Mania

2.2 Epilepsy

2.3 Migraine

2.4 Conversion from Depakote to Depakote ER

2.5 General Dosing Advice

2.6 Dosing in Patients Taking Rufinamide

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Hepatotoxicity

5.2 Structural Birth Defects

5.3 Decreased IQ Following in utero Exposure

5.4 Use in Women of Childbearing Potential

5.5 Pancreatitis

5.6 Urea Cycle Disorders

5.7 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

5.8 Bleeding and Other Hematopoietic Disorders

5.9 Hyperammonemia

5.10 Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy Associated with Concomitant Topiramate Use

5.11 Hypothermia

5.12 Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity Reactions

5.13 Interaction with Carbapenem Antibiotics

5.14 Somnolence in the Elderly

5.15 Monitoring: Drug Plasma Concentration

5.16 Effect on Ketone and Thyroid Function Tests

5.17 Effect on HIV and CMV Viruses Replication

5.18 Medication Residue in the Stool

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Mania

6.2 Epilepsy

6.3 Migraine

6.4 Post-Marketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Effects of Co-Administered Drugs on Valproate Clearance

7.2 Effects of Valproate on Other Drugs

7.3 Topiramate

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Effect of Disease

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Mania

14.2 Epilepsy

14.3 Migraine

15 REFERENCES

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: LIFE THREATENING ADVERSE REACTIONS

Hepatotoxicity

General Population: Hepatic failure resulting in fatalities has occurred in patients receiving valproate and its derivatives. These incidents usually have occurred during the first six months of treatment. Serious or fatal hepatotoxicity may be preceded by non-specific symptoms such as malaise, weakness, lethargy, facial edema, anorexia, and vomiting. In patients with epilepsy, a loss of seizure control may also occur. Patients should be monitored closely for appearance of these symptoms. Serum liver tests should be performed prior to therapy and at frequent intervals thereafter, especially during the first six months [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)] .

Children under the age of two years are at a considerably increased risk of developing fatal hepatotoxicity, especially those on multiple anticonvulsants, those with congenital metabolic disorders, those with severe seizure disorders accompanied by mental retardation, and those with organic brain disease. When Depakote ER is used in this patient group, it should be used with extreme caution and as a sole agent. The benefits of therapy should be weighed against the risks. The incidence of fatal hepatotoxicity decreases considerably in progressively older patient groups.

Patients with Mitochondrial Disease: There is an increased risk of valproate-induced acute liver failure and resultant deaths in patients with hereditary neurometabolic syndromes caused by DNA mutations of the mitochondrial DNA Polymerase γ (POLG) gene (e.g. Alpers Huttenlocher Syndrome). Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients known to have mitochondrial disorders caused by POLG mutations and children under two years of age who are clinically suspected of having a mitochondrial disorder [see Contraindications (4)] . In patients over two years of age who are clinically suspected of having a hereditary mitochondrial disease, Depakote ER should only be used after other anticonvulsants have failed. This older group of patients should be closely monitored during treatment with Depakote ER for the development of acute liver injury with regular clinical assessments and serum liver testing. POLG mutation screening should be performed in accordance with current clinical practice [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)] .

Fetal Risk

Valproate can cause major congenital malformations, particularly neural tube defects (e.g., spina bifida). In addition, valproate can cause decreased IQ scores and neurodevelopmental disordersfollowing in utero exposure.

Valproate is therefore contraindicated for prophylaxis of migraineheadaches in pregnant women and in women of childbearing potential who are not using effective contraception[see Contraindications (4)] . Valproate should not be used to treat women with epilepsy or bipolar disorder who are pregnant or who plan to become pregnant unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable.

Valproate should not be administered to a woman of childbearing potential unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable. In such situations, effective contraception should be used [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2, 5.3, 5.4)] .

A Medication Guide describing the risks of valproate is available for patients [see Patient Counseling Information (17)] .

Pancreatitis

Cases of life-threatening pancreatitis have been reported in both children and adults receiving valproate. Some of the cases have been described as hemorrhagic with a rapid progression from initial symptoms to death. Cases have been reported shortly after initial use as well as after several years of use. Patients and guardians should be warned that abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or anorexia can be symptoms of pancreatitis that require prompt medical evaluation. If pancreatitis is diagnosed, valproate should ordinarily be discontinued. Alternative treatment for the underlying medical condition should be initiated as clinically indicated [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)] .

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Mania

Depakote ER is a valproate and is indicated for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder, with or without psychotic features. A manic episode is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood. Typical symptoms of mania include pressure of speech, motor hyperactivity, reduced need for sleep, flight of ideas, grandiosity, poor judgment, aggressiveness, and possible hostility. A mixed episode is characterized by the criteria for a manic episode in conjunction with those for a major depressive episode (depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities).

The efficacy of Depakote ER is based in part on studies of Depakote (divalproex sodium delayed release tablets) in this indication, and was confirmed in a 3-week trial with patients meeting DSM-IV TR criteria for bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed type, who were hospitalized for acute mania [see Clinical Studies (14.1)] .

The effectiveness of valproate for long-term use in mania, i.e., more than 3 weeks, has not been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials. Therefore, healthcare providers who elect to use Depakote ER for extended periods should continually reevaluate the long-term risk-benefits of the drug for the individual patient.

1.2 Epilepsy

Depakote ER is indicated as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in the treatment of adult patients and pediatric patients down to the age of 10 years with complex partial seizures that occur either in isolation or in association with other types of seizures. Depakote ER is also indicated for use as sole and adjunctive therapy in the treatment of simple and complex absence seizures in adults and children 10 years of age or older, and adjunctively in adults and children 10 years of age or older with multiple seizure types that include absence seizures.

Simple absence is defined as very brief clouding of the sensorium or loss of consciousness accompanied by certain generalized epileptic discharges without other detectable clinical signs. Complex absence is the term used when other signs are also present.

1.3 Migraine

Depakote ER is indicated for prophylaxis of migraine headaches. There is no evidence that Depakote ER is useful in the acute treatment of migraine headaches.

1.4 Important Limitations

Because of the risk to the fetus of decreased IQ, , neural tube defects, and other major congenital malformations, which may occur very early in pregnancy, valproate should not be used to unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable. , . Because of the risk to the fetus of decreased IQ, neurodevelopmental disorders, neural tube defects, and other major congenital malformations, which may occur very early in pregnancy, valproate should not be used to treat women with epilepsy or bipolar disorder who are pregnant or who plan to become pregnant unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable. Valproate should not be administered to a woman of childbearing potential unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2, 5.3, 5.4), Use in Specific Populations (8.1), and Patient Counseling Information (17)] .

. For prophylaxis of migraine headaches, Depakote ER is contraindicated in women who are pregnant and in women of childbearing potential who are not using effective contraception [see Contraindications (4)] .

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Depakote ER is an extended-release product intended for once-a-day oral administration. Depakote ER tablets should be swallowed whole and should not be crushed or chewed.

2.1 Mania

Depakote ER tablets are administered orally. The recommended initial dose is 25 mg/kg/day given once daily. The dose should be increased as rapidly as possible to achieve the lowest therapeutic dose which produces the desired clinical effect or the desired range of plasma concentrations. In a placebo-controlled clinical trial of acute mania or mixed type, patients were dosed to a clinical response with a trough plasma concentration between 85 and 125 mcg/mL. The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day.

There is no body of evidence available from controlled trials to guide a clinician in the longer term management of a patient who improves during Depakote ER treatment of an acute manic episode. While it is generally agreed that pharmacological treatment beyond an acute response in mania is desirable, both for maintenance of the initial response and for prevention of new manic episodes, there are no data to support the benefits of Depakote ER in such longer-term treatment (i.e., beyond 3 weeks).

2.2 Epilepsy

Depakote ER (divalproex sodium) extended-release tablets are administered orally, and must be swallowed whole. As Depakote ER dosage is titrated upward, concentrations of clonazepam, diazepam, ethosuximide, lamotrigine, tolbutamide, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and/or phenytoin may be affected [see Drug Interactions (7.2)] .

For adults and children 10 years of age or older.

Depakote ER has not been systematically studied as initial therapy. Patients should initiate therapy at 10 to 15 mg/kg/day. The dosage should be increased by 5 to 10 mg/kg/week to achieve optimal clinical response. Ordinarily, optimal clinical response is achieved at daily doses below 60 mg/kg/day. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 to 100 mcg/mL). No recommendation regarding the safety of valproate for use at doses above 60 mg/kg/day can be made.

The probability of thrombocytopenia increases significantly at total trough valproate plasma concentrations above 110 mcg/mL in females and 135 mcg/mL in males. The benefit of improved seizure control with higher doses should be weighed against the possibility of a greater incidence of adverse reactions.

Patients should initiate therapy at 10 to 15 mg/kg/day. The dosage should be increased by 5 to 10 mg/kg/week to achieve optimal clinical response. Ordinarily, optimal clinical response is achieved at daily doses below 60 mg/kg/day. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 - 100 mcg/mL). No recommendation regarding the safety of valproate for use at doses above 60 mg/kg/day can be made.

Concomitant antiepilepsy drug (AED) dosage can ordinarily be reduced by approximately 25% every 2 weeks. This reduction may be started at initiation of Depakote ER therapy, or delayed by 1 to 2 weeks if there is a concern that seizures are likely to occur with a reduction. The speed and duration of withdrawal of the concomitant AED can be highly variable, and patients should be monitored closely during this period for increased seizure frequency.

Depakote ER may be added to the patient's regimen at a dosage of 10 to 15 mg/kg/day. The dosage may be increased by 5 to 10 mg/kg/week to achieve optimal clinical response. Ordinarily, optimal clinical response is achieved at daily doses below 60 mg/kg/day. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 to 100 mcg/mL). No recommendation regarding the safety of valproate for use at doses above 60 mg/kg/day can be made.

In a study of adjunctive therapy for complex partial seizures in which patients were receiving either carbamazepine or phenytoin in addition to valproate, no adjustment of carbamazepine or phenytoin dosage was needed [see Clinical Studies (14.2)] . However, since valproate may interact with these or other concurrently administered AEDs as well as other drugs, periodic plasma concentration determinations of concomitant AEDs are recommended during the early course of therapy [see Drug Interactions (7)] .

Simple and Complex Absence Seizures

The recommended initial dose is 15 mg/kg/day, increasing at one week intervals by 5 to 10 mg/kg/day until seizures are controlled or side effects preclude further increases. The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day.

A good correlation has not been established between daily dose, serum concentrations, and therapeutic effect. However, therapeutic valproate serum concentration for most patients with absence seizures is considered to range from 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Some patients may be controlled with lower or higher serum concentrations [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)] .

As Depakote ER dosage is titrated upward, blood concentrations of phenobarbital and/or phenytoin may be affected [see Drug Interactions (7.2)] .

Antiepilepsy drugs should not be abruptly discontinued in patients in whom the drug is administered to prevent major seizures because of the strong possibility of precipitating status epilepticus with attendant hypoxia and threat to life.

2.3 Migraine

Depakote ER is indicated for prophylaxis of migraine headaches in adults.

The recommended starting dose is 500 mg once daily for 1 week, thereafter increasing to 1,000 mg once daily. Although doses other than 1,000 mg once daily of Depakote ER have not been evaluated in patients with migraine, the effective dose range of Depakote (divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets) in these patients is 500-1,000 mg/day. As with other valproate products, doses of Depakote ER should be individualized and dose adjustment may be necessary. If a patient requires smaller dose adjustments than that available with Depakote ER, Depakote should be used instead.

2.4 Conversion from Depakote to Depakote ER

In adult patients and pediatric patients 10 years of age or older with epilepsy previously receiving Depakote, Depakote ER should be administered once-daily using a dose 8 to 20% higher than the total daily dose of Depakote (Table 1). For patients whose Depakote total daily dose cannot be directly converted to Depakote ER, consideration may be given at the clinician’s discretion to increase the patient’s Depakote total daily dose to the next higher dosage before converting to the appropriate total daily dose of Depakote ER.

Table 1. Dose Conversion Depakote Depakote ER Total Daily Dose (mg) (mg) 500* - 625 750 750* - 875 1,000 1,000*-1,125 1,250 1,250-1,375 1,500 1,500-1,625 1,750 1,750 2,000 1,875-2,000 2,250 2,125-2,250 2,500 2,375 2,750 2,500-2,750 3,000 2,875 3,250 3,000-3,125 3,500 * These total daily doses of Depakote cannot be directly converted to an 8 to 20% higher total daily dose of Depakote ER because the required dosing strengths of Depakote ER are not available. Consideration may be given at the clinician's discretion to increase the patient's Depakote total daily dose to the next higher dosage before converting to the appropriate total daily dose of Depakote ER. There is insufficient data to allow a conversion factor recommendation for patients with DEPAKOTE doses above 3,125 mg/day. Plasma valproate C min concentrations for DEPAKOTE ER on average are equivalent to DEPAKOTE, but may vary across patients after conversion. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 to 100 mcg/mL) [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)] .

2.5 General Dosing Advice

Due to a decrease in unbound clearance of valproate and possibly a greater sensitivity to somnolence in the elderly, the starting dose should be reduced in these patients. Starting doses in the elderly lower than 250 mg can only be achieved by the use of Depakote. Dosage should be increased more slowly and with regular monitoring for fluid and nutritional intake, dehydration, somnolence, and other adverse reactions. Dose reductions or discontinuation of valproate should be considered in patients with decreased food or fluid intake and in patients with excessive somnolence. The ultimate therapeutic dose should be achieved on the basis of both tolerability and clinical response [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14), Use in Specific Populations (8.5), and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)] .

Dose-Related Adverse Reactions

The frequency of adverse effects (particularly elevated liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia) may be dose-related. The probability of thrombocytopenia appears to increase significantly at total valproate concentrations of ≥ 110 mcg/mL (females) or ≥ 135 mcg/mL (males) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)] . The benefit of improved therapeutic effect with higher doses should be weighed against the possibility of a greater incidence of adverse reactions.

Patients who experience G.I. irritation may benefit from administration of the drug with food or by slowly building up the dose from an initial low level.

Patients should be informed to take Depakote ER every day as prescribed. If a dose is missed it should be taken as soon as possible, unless it is almost time for the next dose. If a dose is skipped, the patient should not double the next dose.

2.6 Dosing in Patients Taking Rufinamide

Patients stabilized on rufinamide before being prescribed valproate should begin valproate therapy at a low dose, and titrate to a clinically effective dose [see Drug Interactions (7.2)] .

-

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Depakote ER 250 mg is available as white ovaloid tablets with the “a” logo and the code (HF). Each Depakote ER tablet contains divalproex sodium equivalent to 250 mg of valproic acid.

Depakote ER 500 mg is available as gray ovaloid tablets with the “a” logo and the code HC. Each Depakote ER tablet contains divalproex sodium equivalent to 500 mg of valproic acid.

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Depakote ER should not be administered to patients with hepatic disease or significant hepatic dysfunction [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients known to have mitochondrial disorders caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (POLG; e.g., Alpers-Huttenlocher Syndrome) and children under two years of age who are suspected of having a POLG-related disorder [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)] .

- Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to the drug [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)].

- Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients with known urea cycle disorders [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

- For use in prophylaxis of migraine headaches: Depakote ER is contraindicated in women who are pregnant and in women of childbearing potential who are not using effective contraception [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2, 5.3, 5.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.1)] . For use in prophylaxis of migraine headaches: Depakote ER is contraindicated in women who are pregnant and in women of childbearing potential who are not using effective contraception[see Warnings and Precautions (5.2, 5.3, 5.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.1)]

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Hepatotoxicity

General Information on Hepatotoxicity

Hepatic failure resulting in fatalities has occurred in patients receiving valproate. These incidents usually have occurred during the first six months of treatment. Serious or fatal hepatotoxicity may be preceded by non-specific symptoms such as malaise, weakness, lethargy, facial edema, anorexia, and vomiting. In patients with epilepsy, a loss of seizure control may also occur. Patients should be monitored closely for appearance of these symptoms. Serum liver tests should be performed prior to therapy and at frequent intervals thereafter, especially during the first six months of valproate therapy. However, healthcare providers should not rely totally on serum biochemistry since these tests may not be abnormal in all instances, but should also consider the results of careful interim medical history and physical examination.

Caution should be observed when administering valproate products to patients with a prior history of hepatic disease. Patients on multiple anticonvulsants, children, those with congenital metabolic disorders, those with severe seizure disorders accompanied by mental retardation, and those with organic brain disease may be at particular risk. See below, “Patients with Known or Suspected Mitochondrial Disease.”

Experience has indicated that children under the age of two years are at a considerably increased risk of developing fatal hepatotoxicity, especially those with the aforementioned conditions. When Depakote ER is used in this patient group, it should be used with extreme caution and as a sole agent. The benefits of therapy should be weighed against the risks. In progressively older patient groups experience in epilepsy has indicated that the incidence of fatal hepatotoxicity decreases considerably.

Patients with Known or Suspected Mitochondrial Disease

Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients known to have mitochondrial disorders caused by POLG mutations and children under two years of age who are clinically suspected of having a mitochondrial disorder [see Contraindications (4)] . Valproate-induced acute liver failure and liver-related deaths have been reported in patients with hereditary neurometabolic syndromes caused by mutations in the gene for mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (POLG) (e.g., Alpers-Huttenlocher Syndrome) at a higher rate than those without these syndromes. Most of the reported cases of liver failure in patients with these syndromes have been identified in children and adolescents.

POLG-related disorders should be suspected in patients with a family history or suggestive symptoms of a POLG-related disorder, including but not limited to unexplained encephalopathy, refractory epilepsy (focal, myoclonic), status epilepticus at presentation, developmental delays, psychomotor regression, axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, myopathy cerebellar ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, or complicated migraine with occipital aura. POLG mutation testing should be performed in accordance with current clinical practice for the diagnostic evaluation of such disorders. The A467T and W748S mutations are present in approximately 2/3 of patients with autosomal recessive POLG-related disorders.

In patients over two years of age who are clinically suspected of having a hereditary mitochondrial disease, Depakote ER should only be used after other anticonvulsants have failed. This older group of patients should be closely monitored during treatment with Depakote ER for the development of acute liver injury with regular clinical assessments and serum liver test monitoring.

The drug should be discontinued immediately in the presence of significant hepatic dysfunction, suspected or apparent. In some cases, hepatic dysfunction has progressed in spite of discontinuation of drug [see Boxed Warning and Contraindications (4)] .

5.2 Structural Birth Defects

Valproate can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Pregnancy registry data show that maternal valproate use can cause neural tube defects and other structural abnormalities (e.g., craniofacial defects, cardiovascular malformations, hypospadias, limb malformations). The rate of congenital malformations among babies born to mothers using valproate is about four times higher than the rate among babies born to epileptic mothers using other anti-seizure monotherapies. Evidence suggests that folic acid supplementation prior to conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy decreases the risk for congenital neural tube defects in the general population [see Use in Specific Populations ( 8.1)] .

5.3 Decreased IQ Following in utero Exposure

Valproate can cause decreased IQ scores following in utero exposure. Published epidemiological studies have indicated that children exposed to valproate in utero have lower cognitive test scores than children exposed in utero to either another antiepileptic drug or to no antiepileptic drugs. The largest of these studies 1 is a prospective cohort study conducted in the United States and United Kingdom that found that children with prenatal exposure to valproate (n=62) had lower IQ scores at age 6 (97 [95% C.I. 94-101]) than children with prenatal exposure to the other antiepileptic drug monotherapy treatments evaluated: lamotrigine (108 [95% C.I. 105–110]), carbamazepine (105 [95% C.I. 102–108]), and phenytoin (108 [95% C.I. 104–112]). It is not known when during pregnancy cognitive effects in valproate-exposed children occur. Because the women in this study were exposed to antiepileptic drugs throughout pregnancy, whether the risk for decreased IQ was related to a particular time period during pregnancy could not be assessed.

Although all of the available studies have methodological limitations, the weight of the evidence supports the conclusion that valproate exposure in utero can cause decreased IQ in children.

In animal studies, offspring with prenatal exposure to valproate had malformations similar to those seen in humans and demonstrated neurobehavioral deficits [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)] .

5.4 Use in Women of Childbearing Potential

Because of the risk to the fetus of decreased IQ, , and major congenital malformations (including neural tube defects), which may occur very early in pregnancy, valproate should not be administered to a woman of childbearing potential unless This is especially important when valproate use is considered for a condition not usually associated with permanent injury or death . Women should use effective contraception while using valproate. Because of the risk to the fetus of decreased IQ, neurodevelopmental disorders, and major congenital malformations (including neural tube defects), which may occur very early in pregnancy, valproate should not be administered to a woman of childbearing potential unless other medications have failed to provide adequate symptom control or are otherwise unacceptable. This is especially important when valproate use is considered for a condition not usually associated with permanent injury or death such as prophylaxis of migraine headaches [see Contraindications (4)] . Women should use effective contraception while using valproate.

. Women of childbearing potential should be counseled regularly regarding the relative risks and benefits of valproate use during pregnancy. This is especially important for women planning a pregnancy and for girls at the onset of puberty; alternative therapeutic options should be considered for these patients [see Boxed Warning and Use in Specific Populations (8.1)] .

To prevent major seizures, valproate should not be discontinued abruptly, as this can precipitate status epilepticus with resulting maternal and fetal hypoxia and threat to life. To prevent major seizures, valproate should not be discontinued abruptly, as this can precipitate status epilepticus with resulting maternal and fetal hypoxia and threat to life.

Evidence suggests that folic acid supplementation prior to conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy decreases the risk for congenital neural tube defects in the general population. It is not known whether the risk of neural tube defects or decreased IQ in the offspring of women receiving valproate is reduced by folic acid supplementation. Dietary folic acid supplementation both prior to conception and during pregnancy should be routinely recommended for patients using valproate.Evidence suggests that folic acid supplementation prior to conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy decreases the risk for congenital neural tube defects in the general population. It is not known whether the risk of neural tube defects or decreased IQ in the offspring of women receiving valproate is reduced by folic acid supplementation. Dietary folic acid supplementation both prior to conception and during pregnancy should be routinely recommended for patients using valproate.

5.5 Pancreatitis

Cases of life-threatening pancreatitis have been reported in both children and adults receiving valproate. Some of the cases have been described as hemorrhagic with rapid progression from initial symptoms to death. Some cases have occurred shortly after initial use as well as after several years of use. The rate based upon the reported cases exceeds that expected in the general population and there have been cases in which pancreatitis recurred after rechallenge with valproate. In clinical trials, there were 2 cases of pancreatitis without alternative etiology in 2,416 patients, representing 1,044 patient-years experience. Patients and guardians should be warned that abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or anorexia can be symptoms of pancreatitis that require prompt medical evaluation. If pancreatitis is diagnosed, Depakote ER should ordinarily be discontinued. Alternative treatment for the underlying medical condition should be initiated as clinically indicated [see Boxed Warning] .

5.6 Urea Cycle Disorders

Depakote ER is contraindicated in patients with known urea cycle disorders (UCD).

Hyperammonemic encephalopathy, sometimes fatal, has been reported following initiation of valproate therapy in patients with urea cycle disorders, a group of uncommon genetic abnormalities, particularly ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Prior to the initiation of Depakote ER therapy, evaluation for UCD should be considered in the following patients: 1) those with a history of unexplained encephalopathy or coma, encephalopathy associated with a protein load, pregnancy-related or postpartum encephalopathy, unexplained mental retardation, or history of elevated plasma ammonia or glutamine; 2) those with cyclical vomiting and lethargy, episodic extreme irritability, ataxia, low BUN, or protein avoidance; 3) those with a family history of UCD or a family history of unexplained infant deaths (particularly males); 4) those with other signs or symptoms of UCD. Patients who develop symptoms of unexplained hyperammonemic encephalopathy while receiving valproate therapy should receive prompt treatment (including discontinuation of valproate therapy) and be evaluated for underlying urea cycle disorders [see Contraindications (4) and Warnings and Precautions (5.10)] .

5.7 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including Depakote ER, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI:1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5-100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed.

Table 2 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 2. Risk by indication for antiepileptic drugs in the pooled analysis Indication Placebo Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients Relative Risk: Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients Epilepsy 1.0 3.4 3.5 2.4 Psychiatric 5.7 8.5 1.5 2.9 Other 1.0 1.8 1.9 0.9 Total 2.4 4.3 1.8 1.9 The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing Depakote ER or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

5.8 Bleeding and Other Hematopoietic Disorders

Valproate is associated with dose-related thrombocytopenia. In a clinical trial of valproate as monotherapy in patients with epilepsy, 34/126 patients (27%) receiving approximately 50 mg/kg/day on average, had at least one value of platelets ≤ 75 x 10 9/L. Approximately half of these patients had treatment discontinued, with return of platelet counts to normal. In the remaining patients, platelet counts normalized with continued treatment. In this study, the probability of thrombocytopenia appeared to increase significantly at total valproate concentrations of ≥ 110 mcg/mL (females) or ≥ 135 mcg/mL (males). The therapeutic benefit which may accompany the higher doses should therefore be weighed against the possibility of a greater incidence of adverse effects. Valproate use has also been associated with decreases in other cell lines and myelodysplasia.

Because of reports of cytopenias, inhibition of the secondary phase of platelet aggregation, and abnormal coagulation parameters, (e.g., low fibrinogen, coagulation factor deficiencies, acquired von Willebrand’s disease), measurements of complete blood counts and coagulation tests are recommended before initiating therapy and at periodic intervals. It is recommended that patients receiving Depakote ER be monitored for blood counts and coagulation parameters prior to planned surgery and during pregnancy [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)] . Evidence of hemorrhage, bruising, or a disorder of hemostasis/coagulation is an indication for reduction of the dosage or withdrawal of therapy.

5.9 Hyperammonemia

Hyperammonemia has been reported in association with valproate therapy and may be present despite normal liver function tests. In patients who develop unexplained lethargy and vomiting or changes in mental status, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured. Hyperammonemia should also be considered in patients who present with hypothermia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)] . If ammonia is increased, valproate therapy should be discontinued. Appropriate interventions for treatment of hyperammonemia should be initiated, and such patients should undergo investigation for underlying urea cycle disorders [see Contraindications (4) and Warnings and Precautions (5.6, 5.10)] .

During the placebo controlled pediatric mania trial, one (1) in twenty (20) adolescents (5%) treated with valproate developed increased plasma ammonia levels compared to no (0) patients treated with placebo.

Asymptomatic elevations of ammonia are more common and when present, require close monitoring of plasma ammonia levels. If the elevation persists, discontinuation of valproate therapy should be considered.

5.10 Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy Associated with Concomitant Topiramate Use

Concomitant administration of topiramate and valproate has been associated with hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy in patients who have tolerated either drug alone. Clinical symptoms of hyperammonemic encephalopathy often include acute alterations in level of consciousness and/or cognitive function with lethargy or vomiting. Hypothermia can also be a manifestation of hyperammonemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)] . In most cases, symptoms and signs abated with discontinuation of either drug. This adverse reaction is not due to a pharmacokinetic interaction. Patients with inborn errors of metabolism or reduced hepatic mitochondrial activity may be at an increased risk for hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy. Although not studied, an interaction of topiramate and valproate may exacerbate existing defects or unmask deficiencies in susceptible persons. In patients who develop unexplained lethargy, vomiting, or changes in mental status, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured [see Contraindications (4) and Warnings and Precautions (5.6, 5.9)] .

5.11 Hypothermia

Hypothermia, defined as an unintentional drop in body core temperature to < 35°C (95°F), has been reported in association with valproate therapy both in conjunction with and in the absence of hyperammonemia. This adverse reaction can also occur in patients using concomitant topiramate with valproate after starting topiramate treatment or after increasing the daily dose of topiramate [see Drug Interactions (7.3)] . Consideration should be given to stopping valproate in patients who develop hypothermia, which may be manifested by a variety of clinical abnormalities including lethargy, confusion, coma, and significant alterations in other major organ systems such as the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. Clinical management and assessment should include examination of blood ammonia levels.

5.12 Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity Reactions

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), also known as Multiorgan Hypersensitivity, has been reported in patients taking valproate. DRESS may be fatal or life-threatening. DRESS typically, although not exclusively, presents with fever, rash, and/or lymphadenopathy, in association with other organ system involvement, such as hepatitis, nephritis, hematological abnormalities, myocarditis, or myositis sometimes resembling an acute viral infection. Eosinophilia is often present. Because this disorder is variable in its expression, other organ systems not noted here may be involved. It is important to note that early manifestations of hypersensitivity, such as fever or lymphadenopathy, may be present even though rash is not evident. If such signs or symptoms are present, the patient should be evaluated immediately. Valproate should be discontinued and not be resumed if an alternative etiology for the signs or symptoms cannot be established.

5.13 Interaction with Carbapenem Antibiotics

Carbapenem antibiotics (for example, ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem; this is not a complete list) may reduce serum valproate concentrations to subtherapeutic levels, resulting in loss of seizure control. Serum valproate concentrations should be monitored frequently after initiating carbapenem therapy. Alternative antibacterial or anticonvulsant therapy should be considered if serum valproate concentrations drop significantly or seizure control deteriorates [see Drug Interactions (7.1)] .

5.14 Somnolence in the Elderly

In a double-blind, multicenter trial of valproate in elderly patients with dementia (mean age = 83 years), doses were increased by 125 mg/day to a target dose of 20 mg/kg/day. A significantly higher proportion of valproate patients had somnolence compared to placebo, and although not statistically significant, there was a higher proportion of patients with dehydration. Discontinuations for somnolence were also significantly higher than with placebo. In some patients with somnolence (approximately one-half), there was associated reduced nutritional intake and weight loss. There was a trend for the patients who experienced these events to have a lower baseline albumin concentration, lower valproate clearance, and a higher BUN. In elderly patients, dosage should be increased more slowly and with regular monitoring for fluid and nutritional intake, dehydration, somnolence, and other adverse reactions. Dose reductions or discontinuation of valproate should be considered in patients with decreased food or fluid intake and in patients with excessive somnolence [see Dosage and Administration (2.4)] .

5.15 Monitoring: Drug Plasma Concentration

Since valproate may interact with concurrently administered drugs which are capable of enzyme induction, periodic plasma concentration determinations of valproate and concomitant drugs are recommended during the early course of therapy [see Drug Interactions (7)] .

5.16 Effect on Ketone and Thyroid Function Tests

Valproate is partially eliminated in the urine as a keto-metabolite which may lead to a false interpretation of the urine ketone test.

There have been reports of altered thyroid function tests associated with valproate. The clinical significance of these is unknown.

5.17 Effect on HIV and CMV Viruses Replication

There are in vitro studies that suggest valproate stimulates the replication of the HIV and CMV viruses under certain experimental conditions. The clinical consequence, if any, is not known. Additionally, the relevance of these in vitro findings is uncertain for patients receiving maximally suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Nevertheless, these data should be borne in mind when interpreting the results from regular monitoring of the viral load in HIV infected patients receiving valproate or when following CMV infected patients clinically.

5.18 Medication Residue in the Stool

There have been rare reports of medication residue in the stool. Some patients have had anatomic (including ileostomy or colostomy) or functional gastrointestinal disorders with shortened GI transit times. In some reports, medication residues have occurred in the context of diarrhea. It is recommended that plasma valproate levels be checked in patients who experience medication residue in the stool, and patients’ clinical condition should be monitored. If clinically indicated, alternative treatment may be considered.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are described below and elsewhere in the labeling:

- Hepatic failure [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Birth defects [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Decreased IQ following in utero exposure [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Pancreatitis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Hyperammonemic encephalopathy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6, 5.9, 5.10)]

- Suicidal behavior and ideation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Bleeding and other hematopoietic disorders [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Hypothermia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan hypersensitivity reactions [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)]

- Somnolence in the elderly [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14)]

Because clinical studies are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical studies of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical studies of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Information on pediatric adverse reactions is presented in section 8.

6.1 Mania

The incidence of treatment-emergent events has been ascertained based on combined data from two three week placebo-controlled clinical trials of Depakote ER in the treatment of manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder.

Table 3 summarizes those adverse reactions reported for patients in these trials where the incidence rate in the Depakote ER-treated group was greater than 5% and greater than the placebo incidence.

Table 3. Adverse Reactions Reported by > 5% of Depakote-Treated Patients During

Placebo-Controlled Trials of Acute Mania 1Adverse Event Depakote ER

(n=338)Placebo

(n=263)Somnolence 26% 14% Dyspepsia 23% 11% Nausea 19% 13% Vomiting 13% 5% Diarrhea 12% 8% Dizziness 12% 7% Pain 11% 10% Abdominal Pain 10% 5% Accidental Injury 6% 5% Asthenia 6% 5% Pharyngitis 6% 5% 1 The following adverse reactions/event occurred at an equal or greater incidence for placebo than for Depakote ER: headache The following additional adverse reactions were reported by greater than 1% of the Depakote ER-treated patients in controlled clinical trials:

Body as a Whole: Back Pain, Chills, Chills and Fever, Drug Level Increased, Flu Syndrome, Infection, Infection Fungal, Neck Rigidity.

Cardiovascular System: Arrhythmia, Hypertension, Hypotension, Postural Hypotension.

Digestive System: Constipation, Dry Mouth, Dysphagia, Fecal Incontinence, Flatulence, Gastroenteritis, Glossitis, Gum Hemorrhage, Mouth Ulceration.

Hemic and Lymphatic System: Anemia, Bleeding Time Increased, Ecchymosis, Leucopenia.

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: Hypoproteinemia, Peripheral Edema.

Musculoskeletal System: Arthrosis, Myalgia.

Nervous System: Abnormal Gait, Agitation, Catatonic Reaction, Dysarthria, Hallucinations, Hypertonia, Hypokinesia, Psychosis, Reflexes Increased, Sleep Disorder, Tardive Dyskinesia, Tremor.

Respiratory System: Hiccup, Rhinitis.

Skin and Appendages: Discoid Lupus Erythematosus, Erythema Nodosum, Furunculosis, Maculopapular Rash, Pruritus, Rash, Seborrhea, Sweating, Vesiculobullous Rash.

Special Senses: Conjunctivitis, Dry Eyes, Eye Disorder, Eye Pain, Photophobia, Taste Perversion.

Urogenital System: Cystitis, Urinary Tract Infection, Menstrual Disorder, Vaginitis.

6.2 Epilepsy

Based on a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy for treatment of complex partial seizures, Depakote was generally well tolerated with most adverse reactions rated as mild to moderate in severity. Intolerance was the primary reason for discontinuation in the Depakote-treated patients (6%), compared to 1% of placebo-treated patients.

Table 4 lists treatment-emergent adverse reactions which were reported by ≥ 5% of Depakote-treated patients and for which the incidence was greater than in the placebo group, in the placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy for treatment of complex partial seizures. Since patients were also treated with other antiepilepsy drugs, it is not possible, in most cases, to determine whether the following adverse reactions can be ascribed to Depakote alone, or the combination of Depakote and other antiepilepsy drugs.

Table 4. Adverse Reactions Reported by ≥ 5% of Patients Treated with Valproate During Placebo-Controlled Trial of Adjunctive Therapy for Complex Partial Seizures Body System/Event Depakote (%)

(N=77)Placebo (%)

(N=70)Body as a Whole Headache 31 21 Asthenia 27 7 Fever 6 4 Gastrointestinal System Nausea 48 14 Vomiting 27 7 Abdominal Pain 23 6 Diarrhea 13 6 Anorexia 12 0 Dyspepsia 8 4 Constipation 5 1 Nervous System Somnolence 27 11 Tremor 25 6 Dizziness 25 13 Diplopia 16 9 Amblyopia/Blurred Vision 12 9 Ataxia 8 1 Nystagmus 8 1 Emotional Lability 6 4 Thinking Abnormal 6 0 Amnesia 5 1 Respiratory System Flu Syndrome 12 9 Infection 12 6 Bronchitis 5 1 Rhinitis 5 4 Other Alopecia 6 1 Weight Loss 6 0 Table 5 lists treatment-emergent adverse reactions which were reported by ≥ 5% of patients in the high dose valproate group, and for which the incidence was greater than in the low dose group, in a controlled trial of Depakote monotherapy treatment of complex partial seizures. Since patients were being titrated off another antiepilepsy drug during the first portion of the trial, it is not possible, in many cases, to determine whether the following adverse reactions can be ascribed to Depakote alone, or the combination of valproate and other antiepilepsy drugs.

Table 5. Adverse Reactions Reported by ≥ 5% of Patients in the High Dose Group in the Controlled Trial of Valproate Monotherapy for Complex Partial Seizures 1 Body System/Event High Dose (%)

(n=131)Low Dose (%)

(n=134)Body as a Whole Asthenia 21 10 Digestive System Nausea 34 26 Diarrhea 23 19 Vomiting 23 15 Abdominal Pain 12 9 Anorexia 11 4 Dyspepsia 11 10 Hemic/Lymphatic System Thrombocytopenia 24 1 Ecchymosis 5 4 Metabolic/Nutritional Weight Gain 9 4 Peripheral Edema 8 3 Nervous System Tremor 57 19 Somnolence 30 18 Dizziness 18 13 Insomnia 15 9 Nervousness 11 7 Amnesia 7 4 Nystagmus 7 1 Depression 5 4 Respiratory System Infection 20 13 Pharyngitis 8 2 Dyspnea 5 1 Skin and Appendages Alopecia 24 13 Special Senses Amblyopia/Blurred Vision 8 4 Tinnitus 7 1 1 Headache was the only adverse event that occurred in ≥5% of patients in the high dose group and at an equal or greater incidence in the low dose group. The following additional adverse reactions were reported by greater than 1% but less than 5% of the 358 patients treated with valproate in the controlled trials of complex partial seizures:

Body as a Whole: Back pain, chest pain, malaise.

Cardiovascular System: Tachycardia, hypertension, palpitation.

Digestive System: Increased appetite, flatulence, hematemesis, eructation, pancreatitis, periodontal abscess.

Hemic and Lymphatic System: Petechia.

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: SGOT increased, SGPT increased.

Musculoskeletal System: Myalgia, twitching, arthralgia, leg cramps, myasthenia.

Nervous System: Anxiety, confusion, abnormal gait, paresthesia, hypertonia, incoordination, abnormal dreams, personality disorder.

Respiratory System: Sinusitis, cough increased, pneumonia, epistaxis.

Skin and Appendages: Rash, pruritus, dry skin.

Special Senses: Taste perversion, abnormal vision, deafness, otitis media.

Urogenital System: Urinary incontinence, vaginitis, dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, urinary frequency.

6.3 Migraine

Based on two placebo-controlled clinical trials and their long term extension, valproate was generally well tolerated with most adverse reactions rated as mild to moderate in severity. Of the 202 patients exposed to valproate in the placebo-controlled trials, 17% discontinued for intolerance. This is compared to a rate of 5% for the 81 placebo patients. Including the long term extension study, the adverse reactions reported as the primary reason for discontinuation by ≥ 1% of 248 valproate-treated patients were alopecia (6%), nausea and/or vomiting (5%), weight gain (2%), tremor (2%), somnolence (1%), elevated SGOT and/or SGPT (1%), and depression (1%).

Table 6 includes those adverse reactions reported for patients in the placebo-controlled trial where the incidence rate in the Depakote ER-treated group was greater than 5% and was greater than that for placebo patients.

Table 6. Adverse Reactions Reported by >5% of Depakote ER-Treated Patients During the Migraine Placebo-Controlled Trial with a Greater Incidence than Patients Taking Placebo 1 Body System

EventDepakote ER

(n=122)Placebo

(n=115)Gastrointestinal System Nausea 15% 9% Dyspepsia 7% 4% Diarrhea 7% 3% Vomiting 7% 2% Abdominal Pain 7% 5% Nervous System Somnolence 7% 2% Other Infection 15% 14% 1 The following adverse reactions occurred in greater than 5% of Depakote ER-treated patients and at a greater incidence for placebo than for Depakote ER: asthenia and flu syndrome. The following additional adverse reactions were reported by greater than 1% but not more than 5% of Depakote ER-treated patients and with a greater incidence than placebo in the placebo-controlled clinical trial for migraine prophylaxis:

Body as a Whole: Accidental injury, viral infection.

Digestive System: Increased appetite, tooth disorder.

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: Edema, weight gain.

Nervous System: Abnormal gait, dizziness, hypertonia, insomnia, nervousness, tremor, vertigo.

Respiratory System: Pharyngitis, rhinitis.

Table 7 includes those adverse reactions reported for patients in the placebo-controlled trials where the incidence rate in the valproate-treated group was greater than 5% and was greater than that for placebo patients.

Table 7. Adverse Reactions Reported by > 5% of Valproate-Treated Patients During Migraine Placebo-Controlled Trials with a Greater Incidence than Patients Taking Placebo 1 Body System

ReactionDepakote

(n=202)Placebo

(n=81)Gastrointestinal System Nausea 31% 10% Dyspepsia 13% 9% Diarrhea 12% 7% Vomiting 11% 1% Abdominal Pain 9% 4% Increased Appetite 6% 4% Nervous System Asthenia 20% 9% Somnolence 17% 5% Dizziness 12% 6% Tremor 9% 0% Other Weight Gain 8% 2% Back Pain 8% 6% Alopecia 7% 1% 1 The following adverse reactions occurred in greater than 5% of Depakote-treated patients and at a greater incidence for placebo than for Depakote: flu syndrome and pharyngitis. The following additional adverse reactions were reported by greater than 1% but not more than 5% of the 202 valproate-treated patients in the controlled clinical trials:

Cardiovascular System: Vasodilatation.

Digestive System: Constipation, dry mouth, flatulence, and stomatitis.

Hemic and Lymphatic System: Ecchymosis.

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: Peripheral edema.

Musculoskeletal System: Leg cramps.

Nervous System: Abnormal dreams, confusion, paresthesia, speech disorder, and thinking abnormalities.

Respiratory System: Dyspnea, and sinusitis.

6.4 Post-Marketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post approval use of Depakote. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Dermatologic: Hair texture changes, hair color changes, photosensitivity, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, nail and nail bed disorders, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Psychiatric: Emotional upset, psychosis, aggression, psychomotor hyperactivity, hostility, disturbance in attention, learning disorder, and behavioral deterioration.

Neurologic: Paradoxical convulsion, parkinsonism

There have been several reports of acute or subacute cognitive decline and behavioral changes (apathy or irritability) with cerebral pseudoatrophy on imaging associated with valproate therapy; both the cognitive/behavioral changes and cerebral pseudoatrophy reversed partially or fully after valproate discontinuation.

There have been reports of acute or subacute encephalopathy in the absence of elevated ammonia levels, elevated valproate levels, or neuroimaging changes. The encephalopathy reversed partially or fully after valproate discontinuation.

Musculoskeletal: Fractures, decreased bone mineral density, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and weakness.

Hematologic: Relative lymphocytosis, macrocytosis, leukopenia, anemia including macrocytic with or without folate deficiency, bone marrow suppression, pancytopenia, aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, and acute intermittent porphyria.

Endocrine: Irregular menses, secondary amenorrhea, hyperandrogenism, hirsutism, elevated testosterone level, breast enlargement, galactorrhea, parotid gland swelling, polycystic ovary disease, decreased carnitine concentrations, hyponatremia, hyperglycinemia, and inappropriate ADH secretion.

There have been rare reports of Fanconi's syndrome occurring chiefly in children.

Metabolism and nutrition: Weight gain.

Reproductive: Aspermia, azoospermia, decreased sperm count, decreased spermatozoa motility, male infertility, and abnormal spermatozoa morphology.

Genitourinary: Enuresis and urinary tract infection.

Other: Allergic reaction, anaphylaxis, developmental delay, bone pain, bradycardia, and cutaneous vasculitis.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Effects of Co-Administered Drugs on Valproate Clearance

Drugs that affect the level of expression of hepatic enzymes, particularly those that elevate levels of glucuronosyltransferases (such as ritonavir), may increase the clearance of valproate. For example, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital (or primidone) can double the clearance of valproate. Thus, patients on monotherapy will generally have longer half-lives and higher concentrations than patients receiving polytherapy with antiepilepsy drugs.

In contrast, drugs that are inhibitors of cytochrome P450 isozymes, e.g., antidepressants, may be expected to have little effect on valproate clearance because cytochrome P450 microsomal mediated oxidation is a relatively minor secondary metabolic pathway compared to glucuronidation and beta-oxidation.

Because of these changes in valproate clearance, monitoring of valproate and concomitant drug concentrations should be increased whenever enzyme inducing drugs are introduced or withdrawn.

The following list provides information about the potential for an influence of several commonly prescribed medications on valproate pharmacokinetics. The list is not exhaustive nor could it be, since new interactions are continuously being reported.

Drugs for which a potentially important interaction has been observed

A study involving the co-administration of aspirin at antipyretic doses (11 to 16 mg/kg) with valproate to pediatric patients (n=6) revealed a decrease in protein binding and an inhibition of metabolism of valproate. Valproate free fraction was increased 4-fold in the presence of aspirin compared to valproate alone. The β-oxidation pathway consisting of 2-E-valproic acid, 3-OH-valproic acid, and 3-keto valproic acid was decreased from 25% of total metabolites excreted on valproate alone to 8.3% in the presence of aspirin. Whether or not the interaction observed in this study applies to adults is unknown, but caution should be observed if valproate and aspirin are to be co-administered.

A clinically significant reduction in serum valproic acid concentration has been reported in patients receiving carbapenem antibiotics (for example, ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem; this is not a complete list) and may result in loss of seizure control. The mechanism of this interaction is not well understood. Serum valproic acid concentrations should be monitored frequently after initiating carbapenem therapy. Alternative antibacterial or anticonvulsant therapy should be considered if serum valproic acid concentrations drop significantly or seizure control deteriorates [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)] .

Estrogen-Containing Hormonal Contraceptives

Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives may increase the clearance of valproate, which may result in decreased concentration of valproate and potentially increased seizure frequency. Prescribers should monitor serum valproate concentrations and clinical response when adding or discontinuing estrogen containing products.

A study involving the co-administration of 1,200 mg/day of felbamate with valproate to patients with epilepsy (n=10) revealed an increase in mean valproate peak concentration by 35% (from 86 to 115 mcg/mL) compared to valproate alone. Increasing the felbamate dose to 2,400 mg/day increased the mean valproate peak concentration to 133 mcg/mL (another 16% increase). A decrease in valproate dosage may be necessary when felbamate therapy is initiated.

A study involving the administration of a single dose of valproate (7 mg/kg) 36 hours after 5 nights of daily dosing with rifampin (600 mg) revealed a 40% increase in the oral clearance of valproate. Valproate dosage adjustment may be necessary when it is co-administered with rifampin.

Drugs for which either no interaction or a likely clinically unimportant interaction has been observed

A study involving the co-administration of valproate 500 mg with commonly administered antacids (Maalox, Trisogel, and Titralac - 160 mEq doses) did not reveal any effect on the extent of absorption of valproate.

A study involving the administration of 100 to 300 mg/day of chlorpromazine to schizophrenic patients already receiving valproate (200 mg BID) revealed a 15% increase in trough plasma levels of valproate.

A study involving the administration of 6 to 10 mg/day of haloperidol to schizophrenic patients already receiving valproate (200 mg BID) revealed no significant changes in valproate trough plasma levels.

Cimetidine and ranitidine do not affect the clearance of valproate.

7.2 Effects of Valproate on Other Drugs

Valproate has been found to be a weak inhibitor of some P450 isozymes, epoxide hydrase, and glucuronosyltransferases.

The following list provides information about the potential for an influence of valproate co-administration on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of several commonly prescribed medications. The list is not exhaustive, since new interactions are continuously being reported.

Drugs for which a potentially important valproate interaction has been observed

Administration of a single oral 50 mg dose of amitriptyline to 15 normal volunteers (10 males and 5 females) who received valproate (500 mg BID) resulted in a 21% decrease in plasma clearance of amitriptyline and a 34% decrease in the net clearance of nortriptyline. Rare postmarketing reports of concurrent use of valproate and amitriptyline resulting in an increased amitriptyline level have been received. Concurrent use of valproate and amitriptyline has rarely been associated with toxicity. Monitoring of amitriptyline levels should be considered for patients taking valproate concomitantly with amitriptyline. Consideration should be given to lowering the dose of amitriptyline/nortriptyline in the presence of valproate.

Carbamazepine/carbamazepine-10,11-Epoxide

Serum levels of carbamazepine (CBZ) decreased 17% while that of carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide (CBZ-E) increased by 45% upon co-administration of valproate and CBZ to epileptic patients.

The concomitant use of valproate and clonazepam may induce absence status in patients with a history of absence type seizures.

Valproate displaces diazepam from its plasma albumin binding sites and inhibits its metabolism. Co-administration of valproate (1,500 mg daily) increased the free fraction of diazepam (10 mg) by 90% in healthy volunteers (n=6). Plasma clearance and volume of distribution for free diazepam were reduced by 25% and 20%, respectively, in the presence of valproate. The elimination half-life of diazepam remained unchanged upon addition of valproate.

Valproate inhibits the metabolism of ethosuximide. Administration of a single ethosuximide dose of 500 mg with valproate (800 to 1,600 mg/day) to healthy volunteers (n=6) was accompanied by a 25% increase in elimination half-life of ethosuximide and a 15% decrease in its total clearance as compared to ethosuximide alone. Patients receiving valproate and ethosuximide, especially along with other anticonvulsants, should be monitored for alterations in serum concentrations of both drugs.

In a steady-state study involving 10 healthy volunteers, the elimination half-life of lamotrigine increased from 26 to 70 hours with valproate co-administration (a 165% increase). The dose of lamotrigine should be reduced when co-administered with valproate. Serious skin reactions (such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) have been reported with concomitant lamotrigine and valproate administration. See lamotrigine package insert for details on lamotrigine dosing with concomitant valproate administration.

Valproate was found to inhibit the metabolism of phenobarbital. Co-administration of valproate (250 mg BID for 14 days) with phenobarbital to normal subjects (n=6) resulted in a 50% increase in half-life and a 30% decrease in plasma clearance of phenobarbital (60 mg single-dose). The fraction of phenobarbital dose excreted unchanged increased by 50% in presence of valproate.

There is evidence for severe CNS depression, with or without significant elevations of barbiturate or valproate serum concentrations. All patients receiving concomitant barbiturate therapy should be closely monitored for neurological toxicity. Serum barbiturate concentrations should be obtained, if possible, and the barbiturate dosage decreased, if appropriate.

Primidone, which is metabolized to a barbiturate, may be involved in a similar interaction with valproate.

Valproate displaces phenytoin from its plasma albumin binding sites and inhibits its hepatic metabolism. Co-administration of valproate (400 mg TID) with phenytoin (250 mg) in normal volunteers (n=7) was associated with a 60% increase in the free fraction of phenytoin. Total plasma clearance and apparent volume of distribution of phenytoin increased 30% in the presence of valproate. Both the clearance and apparent volume of distribution of free phenytoin were reduced by 25%.

In patients with epilepsy, there have been reports of breakthrough seizures occurring with the combination of valproate and phenytoin. The dosage of phenytoin should be adjusted as required by the clinical situation.

The concomitant use of valproate and propofol may lead to increased blood levels of propofol. Reduce the dose of propofol when co-administering with valproate. Monitor patients closely for signs of increased sedation or cardiorespiratory depression.

Based on a population pharmacokinetic analysis, rufinamide clearance was decreased by valproate. Rufinamide concentrations were increased by <16% to 70%, dependent on concentration of valproate (with the larger increases being seen in pediatric patients at high doses or concentrations of valproate). Patients stabilized on rufinamide before being prescribed valproate should begin valproate therapy at a low dose, and titrate to a clinically effective dose [see Dosage and Administration (2.6)] . Similarly, patients on valproate should begin at a rufinamide dose lower than 10 mg/kg per day (pediatric patients) or 400 mg per day (adults).

From in vitro experiments, the unbound fraction of tolbutamide was increased from 20% to 50% when added to plasma samples taken from patients treated with valproate. The clinical relevance of this displacement is unknown.

In an in vitro study, valproate increased the unbound fraction of warfarin by up to 32.6%. The therapeutic relevance of this is unknown; however, coagulation tests should be monitored if valproate therapy is instituted in patients taking anticoagulants.

In six patients who were seropositive for HIV, the clearance of zidovudine (100 mg q8h) was decreased by 38% after administration of valproate (250 or 500 mg q8h); the half-life of zidovudine was unaffected.

Drugs for which either no interaction or a likely clinically unimportant interaction has been observed

Valproate had no effect on any of the pharmacokinetic parameters of acetaminophen when it was concurrently administered to three epileptic patients.

In psychotic patients (n=11), no interaction was observed when valproate was co-administered with clozapine.

Co-administration of valproate (500 mg BID) and lithium carbonate (300 mg TID) to normal male volunteers (n=16) had no effect on the steady-state kinetics of lithium.

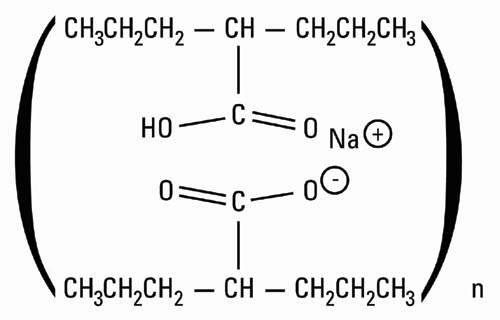

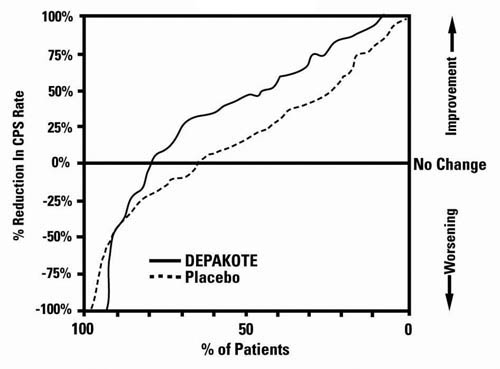

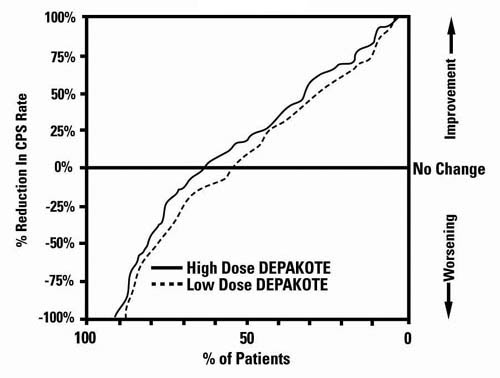

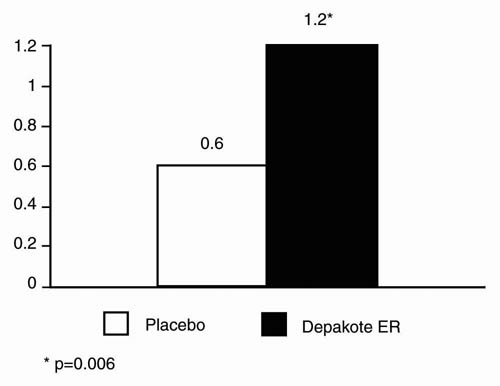

Concomitant administration of valproate (500 mg BID) and lorazepam (1 mg BID) in normal male volunteers (n=9) was accompanied by a 17% decrease in the plasma clearance of lorazepam.