These highlights do not include all the information needed to use VIGABATRIN TABLETS safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for VIGABATRIN TABLETS.VIGABATRIN TABLETS, for oral useInitial U.S. Approval: 2009

VIGABATRIN by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

VIGABATRIN by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Padagis US LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

VIGABATRIN- vigabatrin tablet

Padagis US LLC

----------

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATIONThese highlights do not include all the information needed to use VIGABATRIN TABLETS safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for VIGABATRIN TABLETS.

VIGABATRIN TABLETS, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 2009 WARNING: PERMANENT VISION LOSSSee full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

Risk increases with increasing dose and cumulative exposure, but there is no dose or exposure to vigabatrin known to be free of risk of vision loss (5.1). Risk of new and worsening vision loss continues as long as vigabatrin is used, and possibly after discontinuing vigabatrin (5.1). Baseline and periodic vision assessment is recommended for patients on vigabatrin. However, this assessment cannot always prevent vision damage (5.1). Vigabatrin is available only through a restricted program called the Vigabatrin REMS Program (5.2). INDICATIONS AND USAGEVigabatrin tablets are indicated for the treatment of:

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATIONRefractory Complex Partial Seizures

Infantile Spasms

Renal Impairment: Dose adjustment recommended (2.4, 8.5, 8.6) DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

CONTRAINDICATIONSNone (4) WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

ADVERSE REACTIONSRefractory Complex Partial Seizures Most common adverse reactions in controlled studies include (incidence ≥5% over placebo):

Infantile Spasms (incidence >5% and greater than on placebo)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Padagis at 1-866-634-9120 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch. DRUG INTERACTIONSDecreased phenytoin plasma levels: dosage adjustment may be needed (7.1) USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONSSee 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide. Revised: 9/2021 |

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: PERMANENT VISION LOSS

- Vigabatrin can cause permanent bilateral concentric visual field constriction including tunnel vision that can result in disability. In some cases, vigabatrin also can damage the central retina and may decrease visual acuity [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- The onset of vision loss from vigabatrin is unpredictable, and can occur within weeks of starting treatment or sooner, or at any time after starting treatment, even after months or years.

- Symptoms of vision loss from vigabatrin are unlikely to be recognized by patients or caregivers before vision loss is severe. Vision loss of milder severity, while often unrecognized by the patient or caregiver, can still adversely affect function.

- The risk of vision loss increases with increasing dose and cumulative exposure, but there is no dose or exposure known to be free of risk of vision loss.

- Vision assessment is recommended at baseline (no later than 4 weeks after starting vigabatrin), at least every 3 months during therapy, and about 3 to 6 months after the discontinuation of therapy.

- Once detected, vision loss due to vigabatrin is not reversible. It is expected that, even with frequent monitoring, some patients will develop severe vision loss.

- Consider drug discontinuation, balancing benefit and risk, if vision loss is documented.

- Risk of new or worsening vision loss continues as long as vigabatrin is used. It is possible that vision loss can worsen despite discontinuation of vigabatrin.

- Because of the risk of vision loss, vigabatrin should be withdrawn from patients with refractory complex partial seizures who fail to show substantial clinical benefit within 3 months of initiation and within 2-4 weeks of initiation for patients with infantile spasms, or sooner if treatment failure becomes obvious. Patient response to and continued need for vigabatrin should be periodically reassessed.

- Vigabatrin should not be used in patients with, or at high risk of, other types of irreversible vision loss unless the benefits of treatment clearly outweigh the risks.

- Vigabatrin should not be used with other drugs associated with serious adverse ophthalmic effects such as retinopathy or glaucoma unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

- Use the lowest dosage and shortest exposure to vigabatrin consistent with clinical objectives [see Dosage and Administration (2.1)].

The onset of vision loss from vigabatrin is unpredictable, and can occur within weeks of starting treatment or sooner, or at any time after starting treatment, even after months or years.

Symptoms of vision loss from vigabatrin are unlikely to be recognized by patients or caregivers before vision loss is severe. Vision loss of milder severity, while often unrecognized by the patient or caregiver, can still adversely affect function.

The risk of vision loss increases with increasing dose and cumulative exposure, but there is no dose or exposure known to be free of risk of vision loss.

Vision assessment is recommended at baseline (no later than 4 weeks after starting vigabatrin), at least every 3 months during therapy, and about 3 to 6 months after the discontinuation of therapy.

Once detected, vision loss due to vigabatrin is not reversible. It is expected that, even with frequent monitoring, some patients will develop severe vision loss.

Consider drug discontinuation, balancing benefit and risk, if vision loss is documented.

Risk of new or worsening vision loss continues as long as vigabatrin is used. It is possible that vision loss can worsen despite discontinuation of vigabatrin.

Because of the risk of vision loss, vigabatrin should be withdrawn from patients with refractory complex partial seizures who fail to show substantial clinical benefit within 3 months of initiation and within 2-4 weeks of initiation for patients with infantile spasms, or sooner if treatment failure becomes obvious. Patient response to and continued need for vigabatrin should be periodically reassessed.

Vigabatrin should not be used in patients with, or at high risk of, other types of irreversible vision loss unless the benefits of treatment clearly outweigh the risks.

Vigabatrin should not be used with other drugs associated with serious adverse ophthalmic effects such as retinopathy or glaucoma unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

Use the lowest dosage and shortest exposure to vigabatrin consistent with clinical objectives [see Dosage and Administration (2.1)].

Because of the risk of permanent vision loss, vigabatrin is available only through a restricted program under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) called the Vigabatrin REMS Program [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. Further information is available at www.vigabatrinREMS.com or 1-866-244-8175.

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Refractory Complex Partial Seizure (CPS)

Vigabatrin tablets are indicated as adjunctive therapy for adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with refractory complex partial seizures who have inadequately responded to several alternative treatments and for whom the potential benefits outweigh the risk of vision loss [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]. Vigabatrin tablets are not indicated as a first line agent for complex partial seizures.

1.2 Infantile Spasms (IS)

Vigabatrin tablets are indicated as monotherapy for pediatric patients with infantile spasms 1 month to 2 years of age for whom the potential benefits outweigh the potential risk of vision loss [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Important Dosing and Administration Instructions

Dosing

Use the lowest dosage and shortest exposure to vigabatrin tablets consistent with clinical objectives [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

The vigabatrin tablets dosing regimen depends on the indication, age group, weight, and dosage form (tablets or for oral solution) [see Dosage and Administration (2.2, 2.3)]. Patients with impaired renal function require dose adjustment [see Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

Monitoring of vigabatrin tablets plasma concentrations to optimize therapy is not helpful.

Administration

Vigabatrin tablets are given orally with or without food.

If a decision is made to discontinue vigabatrin tablets, the dose should be gradually reduced [see Dosage and Administration (2.2, 2.3) and Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

2.2 Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Adults (Patients 17 Years of Age and Older)

Treatment should be initiated at 1000 mg/day (500 mg twice daily). Total daily dose may be increased in 500 mg increments at weekly intervals depending on response. The recommended dose of vigabatrin tablets in adults is 3000 mg/day (1500 mg twice daily). A 6000 mg/day dose has not been shown to confer additional benefit compared to the 3000 mg/day dose and is associated with an increased incidence of adverse events.

In controlled clinical studies in adults with complex partial seizures, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose 1000 mg/day on a weekly basis until discontinued [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Pediatric (Patients 2 to 16 Years of Age)

The recommended dosage is based on body weight and administered as two divided doses, as shown in Table 1. The dosage may be increased in weekly intervals to the total daily maintenance dosage, depending on response.

Pediatric patients weighing more than 60 kg should be dosed according to adult recommendations.

Table 1. CPS Dosing Recommendations for Pediatric Patients Weighing 10 kg up to 60 kg††

|

Body Weight [kg] |

Total Daily* Starting Dose [mg/day] |

Total Daily* Maintenance Dose† [mg/day] |

|

10 kg to 15 kg |

350 mg |

1050 mg |

|

Greater than 15 kg to 20 kg |

450 mg |

1300 mg |

|

Greater than 20 kg to 25 kg |

500 mg |

1500 mg |

|

Greater than 25 kg to 60 kg |

500 mg |

2000 mg |

* Administered in two divided doses

† Maintenance dose is based on 3000 mg/day adult-equivalent dose

†† Patients weighing more than 60 kg should be dosed according to adult recommendations

In patients with refractory complex partial seizures, vigabatrin tablets should be withdrawn if a substantial clinical benefit is not observed within 3 months of initiating treatment. If, in the clinical judgment of the prescriber, evidence of treatment failure becomes obvious earlier than 3 months, treatment should be discontinued at that time [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

In a controlled study in pediatric patients with complex partial seizures, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose by one third every week for three weeks [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

2.3 Infantile Spasms

The initial daily dosing is 50 mg/kg/day given in two divided doses (25 mg/kg twice daily); subsequent dosing can be titrated by 25 mg/kg/day to 50 mg/kg/day increments every 3 days, up to a maximum of 150 mg/kg/day given in 2 divided doses (75 mg/kg twice daily) [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

Table 2 provides the volume of the 50 mg/mL dosing solution that should be administered as individual doses in infants of various weights.

Table 2. Infant Dosing Table

|

Weight [kg] |

Starting Dose 50 mg/kg/day |

Maximum Dose 150 mg/kg/day |

|

3 |

1.5 mL twice daily |

4.5 mL twice daily |

|

4 |

2 mL twice daily |

6 mL twice daily |

|

5 |

2.5 mL twice daily |

7.5 mL twice daily |

|

6 |

3 mL twice daily |

9 mL twice daily |

|

7 |

3.5 mL twice daily |

10.5 mL twice daily |

|

8 |

4 mL twice daily |

12 mL twice daily |

|

9 |

4.5 mL twice daily |

13.5 mL twice daily |

|

10 |

5 mL twice daily |

15 mL twice daily |

|

11 |

5.5 mL twice daily |

16.5 mL twice daily |

|

12 |

6 mL twice daily |

18 mL twice daily |

|

13 |

6.5 mL twice daily |

19.5 mL twice daily |

|

14 |

7 mL twice daily |

21 mL twice daily |

|

15 |

7.5 mL twice daily |

22.5 mL twice daily |

|

16 |

8 mL twice daily |

24 mL twice daily |

In patients with infantile spasms, vigabatrin tablets should be withdrawn if a substantial clinical benefit is not observed within 2 to 4 weeks. If, in the clinical judgment of the prescriber, evidence of treatment failure becomes obvious earlier than 2 to 4 weeks, treatment should be discontinued at that time [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

In a controlled clinical study in patients with infantile spasms, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose at a rate of 25 mg/kg to 50 mg/kg every 3 to 4 days [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

2.4 Patients with Renal Impairment

Vigabatrin is primarily eliminated through the kidney.

Infants

Information about how to adjust the dose in infants with renal impairment is unavailable.

Adult and pediatric patients 2 years and older

- Mild renal impairment (CLcr >50 to 80 mL/min): dose should be decreased by 25%

- Moderate renal impairment (CLcr >30 to 50 mL/min): dose should be decreased by 50%

- Severe renal impairment (CLcr >10 to 30 mL/min): dose should be decreased by 75%

CLcr in mL/min may be estimated from serum creatinine (mg/dL) using the following formulas:

- Patients 2 to <12 years old: CLcr (mL/min/1.73 m2) = (K × Ht) / Scr

height (Ht) in cm; serum creatinine (Scr) in mg/dL

K (proportionality constant): Female Child (<12 years): K=0.55;

Male Child (<12 years): K=0.70

- Adult and pediatric patients 12 years or older: CLcr (mL/min) = [140-age (years)] × weight (kg) / [72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)] (× 0.85 for female patients)

The effect of dialysis on vigabatrin clearance has not been adequately studied [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3) and Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Vigabatrin Tablets, USP: 500 mg oval-shaped tablets, white, film-coated, biconvex, scored on one side and debossed with "D500" on the other side.

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Permanent Vision Loss

Vigabatrin can cause permanent vision loss. Because of this risk and because, when it is effective, vigabatrin provides an observable symptomatic benefit; patient response and continued need for treatment should be periodically assessed.

Based upon adult studies, 30 percent or more of patients can be affected with bilateral concentric visual field constriction ranging in severity from mild to severe. Severe cases may be characterized by tunnel vision to within 10 degrees of visual fixation, which can result in disability. In some cases, vigabatrin also can damage the central retina and may decrease visual acuity. Symptoms of vision loss from vigabatrin are unlikely to be recognized by patients or caregivers before vision loss is severe. Vision loss of milder severity, while often unrecognized by the patient or caregiver, can still adversely affect function.

Because assessing vision may be difficult in infants and children, the frequency and extent of vision loss is poorly characterized in these patients. For this reason, the understanding of the risk is primarily based on the adult experience. The possibility that vision loss from vigabatrin may be more common, more severe, or have more severe functional consequences in infants and children than in adults cannot be excluded.

The onset of vision loss from vigabatrin is unpredictable and can occur within weeks of starting treatment or sooner, or at any time after starting treatment, even after months or years.

The risk of vision loss increases with increasing dose and cumulative exposure, but there is no dose or exposure known to be free of risk of vision loss.

In patients with refractory complex partial seizures, vigabatrin should be withdrawn if a substantial clinical benefit is not observed within 3 months of initiating treatment. If, in the clinical judgment of the prescriber, evidence of treatment failure becomes obvious earlier than 3 months, treatment should be discontinued at that time [see Dosage and Administration (2.2) and Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

In patients with infantile spasms, vigabatrin should be withdrawn if a substantial clinical benefit is not observed within 2 to 4 weeks. If, in the clinical judgment of the prescriber, evidence of treatment failure becomes obvious earlier than 2 to 4 weeks, treatment should be discontinued at that time [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Vigabatrin should not be used in patients with, or at high risk of, other types of irreversible vision loss unless the benefits of treatment clearly outweigh the risks. The interaction of other types of irreversible vision damage with vision damage from vigabatrin has not been well-characterized, but is likely adverse.

Vigabatrin should not be used with other drugs associated with serious adverse ophthalmic effects such as retinopathy or glaucoma unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

Monitoring of Vision

Monitoring of vision by an ophthalmic professional with expertise in visual field interpretation and the ability to perform dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy of the retina is recommended [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. Because vision testing in infants is difficult, vision loss may not be detected until it is severe. For patients receiving vigabatrin, vision assessment is recommended at baseline (no later than 4 weeks after starting vigabatrin), at least every 3 months while on therapy, and about 3-6 months after the discontinuation of therapy. The diagnostic approach should be individualized for the patient and clinical situation.

In adults and cooperative pediatric patients, perimetry is recommended, preferably by automated threshold visual field testing. Additional testing may also include electrophysiology (e.g., electroretinography [ERG]), retinal imaging (e.g., optical coherence tomography [OCT]), and/or other methods appropriate for the patient. In patients who cannot be tested, treatment may continue according to clinical judgment, with appropriate patient counseling. Because of variability, results from ophthalmic monitoring must be interpreted with caution, and repeat assessment is recommended if results are abnormal or uninterpretable. Repeat assessment in the first few weeks of treatment is recommended to establish if, and to what degree, reproducible results can be obtained, and to guide selection of appropriate ongoing monitoring for the patient.

The onset and progression of vision loss from vigabatrin is unpredictable, and it may occur or worsen precipitously between assessments. Once detected, vision loss due to vigabatrin is not reversible. It is expected that even with frequent monitoring, some vigabatrin patients will develop severe vision loss. Consider drug discontinuation, balancing benefit and risk, if vision loss is documented. It is possible that vision loss can worsen despite discontinuation of vigabatrin.

5.2 Vigabatrin REMS Program

Vigabatrin tablets are available only through a restricted distribution program called the Vigabatrin REMS Program, because of the risk of permanent vision loss.

Notable requirements of the Vigabatrin REMS Program include the following:

- Prescribers must be certified by enrolling in the program, agreeing to counsel patients on the risk of vision loss and the need for periodic monitoring of vision, and reporting any event suggestive of vision loss to Vigabatrin REMS Program.

- Patients must enroll in the program.

- Pharmacies must be certified and must only dispense to patients authorized to receive vigabatrin.

Further information is available at www.vigabatrinREMS.com, or call 1-866-244-8175.

5.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Abnormalities in Infants

Abnormal MRI signal changes characterized by increased T2 signal and restricted diffusion in a symmetric pattern involving the thalamus, basal ganglia, brain stem, and cerebellum have been observed in some infants treated with vigabatrin.

In a retrospective epidemiologic study in infants with infantile spasms (N=205), the prevalence of MRI changes was 22% in vigabatrin-treated patients versus 4% in patients treated with other therapies. In this study, in post marketing experience, and in published literature reports, these changes generally resolved with discontinuation of treatment. In a few patients, the lesion resolved despite continued use. It has been reported that some infants exhibited coincident motor abnormalities, but no causal relationship has been established and the potential for long-term clinical sequelae has not been adequately studied.

Neurotoxicity (brain histopathology and neurobehavioral abnormalities) was observed in rats exposed to vigabatrin during late gestation and the neonatal and juvenile periods of development, and brain histopathological changes were observed in dogs exposed to vigabatrin during the juvenile period of development. The relationship between these findings and the abnormal MRI findings in infants treated with vigabatrin for infantile spasms is unknown [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

The specific pattern of signal changes observed in patients 6 years and younger was not observed in older pediatric and adult patients treated with vigabatrin. In a blinded review of MRI images obtained in prospective clinical trials in patients with refractory complex partial seizures (CPS) 3 years and older (N=656), no difference was observed in anatomic distribution or prevalence of MRI signal changes between vigabatrin treated and placebo treated patients. In the postmarketing setting, MRI changes have also been reported in patients 6 years of age and younger being treated for refractory CPS.

For adults treated with vigabatrin, routine MRI surveillance is unnecessary as there is no evidence that vigabatrin causes MRI changes in this population.

5.4 Neurotoxicity

Intramyelinic Edema (IME) has been reported in postmortem examination of infants being treated for infantile spasms with vigabatrin.

Abnormal MRI signal changes characterized by increased T2 signal and restricted diffusion in a symmetric pattern involving the thalamus, basal ganglia, brain stem, and cerebellum have also been observed in some infants treated for IS with vigabatrin. Studies of the effects of vigabatrin on MRI and evoked potentials (EP) in adult epilepsy patients have demonstrated no clear-cut abnormalities [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

Vacuolation, characterized by fluid accumulation and separation of the outer layers of myelin, has been observed in brain white matter tracts in adult and juvenile rats and adult mice, dogs, and possibly monkeys following administration of vigabatrin. This lesion, referred to as intramyelinic edema (IME), was seen in animals at doses within the human therapeutic range. A no-effect dose was not established in rodents or dogs. In the rat and dog, vacuolation was reversible following discontinuation of vigabatrin treatment, but, in the rat, pathologic changes consisting of swollen or degenerating axons, mineralization, and gliosis were seen in brain areas in which vacuolation had been previously observed. Vacuolation in adult animals was correlated with alterations in MRI and changes in visual and somatosensory EP.

Administration of vigabatrin to rats during the neonatal and juvenile periods of development produced vacuolar changes in the brain gray matter (including the thalamus, midbrain, deep cerebellar nuclei, substantia nigra, hippocampus, and forebrain) which are considered distinct from the IME observed in vigabatrin treated adult animals. Decreased myelination and evidence of oligodendrocyte injury were additional findings in the brains of vigabatrin-treated rats. An increase in apoptosis was seen in some brain regions following vigabatrin exposure during the early postnatal period. Long-term neurobehavioral abnormalities (convulsions, neuromotor impairment, learning deficits) were also observed following vigabatrin treatment of young rats. Administration of vigabatrin to juvenile dogs produced vacuolar changes in the brain gray matter (including the septal nuclei, hippocampus, hypothalamus, thalamus, cerebellum, and globus pallidus). Neurobehavioral effects of vigabatrin were not assessed in the juvenile dog. These effects in young animals occurred at doses lower than those producing neurotoxicity in adult animals and were associated with plasma vigabatrin levels substantially lower than those achieved clinically in infants and children [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1, 8.4)].

In a published study, vigabatrin (200, 400 mg/kg/day) induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the brain of young rats when administered by intraperitoneal injection on postnatal days 5-7.

Administration of vigabatrin to female rats during pregnancy and lactation at doses below those used clinically resulted in hippocampal vacuolation and convulsions in the mature offspring.

5.5 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including vigabatrin, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug treated patients in the trials and none in placebo treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5-100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed. Table 4 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 4. Risk by Indication for Antiepileptic Drugs in the Pooled Analysis

|

Indication |

Placebo Patients with Events per 1000 Patients |

Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients |

Relative Risk: Incidence of Drug Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients |

Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients |

|

Epilepsy |

1.0 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

2.4 |

|

Psychiatric |

5.7 |

8.5 |

1.5 |

2.9 |

|

Other |

1.0 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

0.9 |

|

Total |

2.4 |

4.3 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing vigabatrin or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

5.6 Withdrawal of Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs)

As with all AEDs, vigabatrin should be withdrawn gradually. However, if withdrawal is needed because of a serious adverse event, rapid discontinuation can be considered. Patients and caregivers should be told not to suddenly discontinue vigabatrin therapy.

In controlled clinical studies in adults with complex partial seizures, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose 1000 mg/day on a weekly basis until discontinued.

In a controlled study in pediatric patients with complex partial seizures, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose by one third every week for three weeks.

In a controlled clinical study in patients with infantile spasms, vigabatrin was tapered by decreasing the daily dose at a rate of 25-50 mg/kg every 3-4 days.

5.7 Anemia

In North American controlled trials in adults, 6% of patients (16/280) receiving vigabatrin and 2% of patients (3/188) receiving placebo had adverse events of anemia and/or met criteria for potentially clinically important hematology changes involving hemoglobin, hematocrit, and/or RBC indices. Across U.S. controlled trials, there were mean decreases in hemoglobin of about 3% and 0% in vigabatrin and placebo-treated patients, respectively, and a mean decrease in hematocrit of about 1% in vigabatrin-treated patients compared to a mean gain of about 1% in patients treated with placebo.

In controlled and open-label epilepsy trials in adults and pediatric patients, 3 vigabatrin patients (0.06%, 3/4855) discontinued for anemia and 2 vigabatrin patients experienced unexplained declines in hemoglobin to below 8 g/dL and/or hematocrit below 24%.

5.8 Somnolence and Fatigue

Vigabatrin causes somnolence and fatigue. Patients should be advised not to drive a car or operate other complex machinery until they are familiar with the effects of vigabatrin on their ability to perform such activities.

Pooled data from two vigabatrin controlled trials in adults demonstrated that 24% (54/222) of vigabatrin patients experienced somnolence compared to 10% (14/135) of placebo patients. In those same studies, 28% of vigabatrin patients experienced fatigue compared to 15% (20/135) of placebo patients. Almost 1% of vigabatrin patients discontinued from clinical trials for somnolence and almost 1% discontinued for fatigue.

Pooled data from three vigabatrin controlled trials in pediatric patients demonstrated that 6% (10/165) of vigabatrin patients experienced somnolence compared to 5% (5/104) of placebo patients. In those same studies, 10% (17/165) of vigabatrin patients experienced fatigue compared to 7% (7/104) of placebo patients. No vigabatrin patients discontinued from clinical trials due to somnolence or fatigue.

5.9 Peripheral Neuropathy

Vigabatrin causes symptoms of peripheral neuropathy in adults. Pediatric clinical trials were not designed to assess symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, but observed incidence of symptoms based on pooled data from controlled pediatric studies appeared similar for pediatric patients on vigabatrin and placebo. In a pool of North American controlled and uncontrolled epilepsy studies, 4.2% (19/457) of vigabatrin patients developed signs and/or symptoms of peripheral neuropathy. In the subset of North American placebo- controlled epilepsy trials, 1.4% (4/280) of vigabatrin treated patients and no (0/188) placebo patients developed signs and/or symptoms of peripheral neuropathy. Initial manifestations of peripheral neuropathy in these trials included, in some combination, symptoms of numbness or tingling in the toes or feet, signs of reduced distal lower limb vibration or position sensation, or progressive loss of reflexes, starting at the ankles. Clinical studies in the development program were not designed to investigate peripheral neuropathy systematically and did not include nerve conduction studies, quantitative sensory testing, or skin or nerve biopsy. There is insufficient evidence to determine if development of these signs and symptoms was related to duration of vigabatrin treatment, cumulative dose, or if the findings of peripheral neuropathy were completely reversible upon discontinuation of vigabatrin.

5.10 Weight Gain

Vigabatrin causes weight gain in adult and pediatric patients.

Data pooled from randomized controlled trials in adults found that 17% (77/443) of vigabatrin patients versus 8% (22/275) of placebo patients gained ≥7% of baseline body weight. In these same trials, the mean weight change among vigabatrin patients was 3.5 kg compared to 1.6 kg for placebo patients.

Data pooled from randomized controlled trials in pediatric patients with refractory complex partial seizures found that 47% (77/163) of vigabatrin patients versus 19% (19/102) of placebo patients gained ≥7% of baseline body weight.

In all epilepsy trials, 0.6% (31/4855) of vigabatrin patients discontinued for weight gain. The long term effects of vigabatrin related weight gain are not known. Weight gain was not related to the occurrence of edema.

5.11 Edema

Vigabatrin causes edema in adults. Pediatric clinical trials were not designed to assess edema, but observed incidence of edema-based pooled data from controlled pediatric studies appeared similar for pediatric patients on vigabatrin and placebo.

Pooled data from controlled trials demonstrated increased risk among vigabatrin patients compared to placebo patients for peripheral edema (vigabatrin 2%, placebo 1%), and edema (vigabatrin 1%, placebo 0%). In these studies, one vigabatrin and no placebo patients discontinued for an edema related AE. In adults, there was no apparent association between edema and cardiovascular adverse events such as hypertension or congestive heart failure. Edema was not associated with laboratory changes suggestive of deterioration in renal or hepatic function.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious and otherwise important adverse reactions are described elsewhere in labeling:

- Permanent Vision Loss [see BOXED WARNING and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Abnormalities in Infants [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Neurotoxicity [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Suicidal Behavior and Ideation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Withdrawal of Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Anemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Somnolence and Fatigue [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Peripheral Neuropathy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

- Weight Gain [see Warnings and Precautions (5.10)]

- Edema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]

6.1 Clinical Trial Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

In U.S. and primary non-U.S. clinical studies of 4,079 vigabatrin-treated patients, the most common (≥5%) adverse reactions associated with the use of vigabatrin in combination with other AEDs were headache, somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, convulsion, nasopharyngitis, weight gain, upper respiratory tract infection, visual field defect, depression, tremor, nystagmus, nausea, diarrhea, memory impairment, insomnia, irritability, abnormal coordination, blurred vision, diplopia, vomiting, influenza, pyrexia, and rash.

The adverse reactions most commonly associated with vigabatrin treatment discontinuation in ≥1% of patients were convulsion and depression.

In patients with infantile spasms, the adverse reactions most commonly associated with vigabatrin treatment discontinuation in _1% of patients were infections, status epilepticus, developmental coordination disorder, dystonia, hypotonia, hypertonia, weight gain, and insomnia.

Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Adults

Table 5 lists the adverse reactions that occurred in ≥2% and more than one patient per vigabatrin treated group and that occurred more frequently than in placebo patients from 2 U.S. adjunctive clinical studies of refractory CPS in adults.

Table 5. Reactions in Pooled, Adjunctive Trials in Adults with Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

|

Vigabatrin dosage (mg/day) |

|||

|

Body System Adverse Reaction |

3000 [N=134] % |

6000 [N=43] % |

Placebo [N=135] % |

|

Ear Disorders |

|||

|

Tinnitus |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

Vertigo |

2 |

5 |

1 |

|

Eye Disorders |

|||

|

Blurred vision |

13 |

16 |

5 |

|

Diplopia |

7 |

16 |

3 |

|

Asthenopia |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

Eye pain |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Gastrointestinal Disorders |

|||

|

Diarrhea |

10 |

16 |

7 |

|

Nausea |

10 |

2 |

8 |

|

Vomiting |

7 |

9 |

6 |

|

Constipation |

8 |

5 |

3 |

|

Upper abdominal pain |

5 |

5 |

1 |

|

Dyspepsia |

4 |

5 |

3 |

|

Stomach discomfort |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

Abdominal pain |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Toothache |

2 |

5 |

2 |

|

Abdominal distension |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

General Disorders |

|||

|

Fatigue |

23 |

40 |

16 |

|

Gait disturbance |

6 |

12 |

7 |

|

Asthenia |

5 |

7 |

1 |

|

Edema peripheral |

5 |

7 |

1 |

|

Fever |

4 |

7 |

3 |

|

Chest pain |

1 |

5 |

1 |

|

Thirst |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Malaise |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Infections |

|||

|

Nasopharyngitis |

14 |

9 |

10 |

|

Upper respiratory tract infection |

7 |

9 |

6 |

|

Influenza |

5 |

7 |

4 |

|

Urinary tract infection |

4 |

5 |

0 |

|

Bronchitis |

0 |

5 |

1 |

|

Injury | |||

|

Contusion |

3 |

5 |

2 |

|

Joint sprain |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Muscle strain |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Wound secretion |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Metabolism and NutritionDisorders |

|||

|

Increased appetite |

1 |

5 |

1 |

|

Weight gain |

6 |

14 |

3 |

|

Musculoskeletal Disorders | |||

|

Arthralgia |

10 |

5 |

3 |

|

Back pain |

4 |

7 |

2 |

|

Pain in extremity |

6 |

2 |

4 |

|

Myalgia |

3 |

5 |

1 |

|

Muscle twitching |

1 |

9 |

1 |

|

Muscle spasms |

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

Nervous System Disorders | |||

|

Headache |

33 |

26 |

31 |

|

Somnolence |

22 |

26 |

13 |

|

Dizziness |

24 |

26 |

17 |

|

Nystagmus |

13 |

19 |

9 |

|

Tremor |

15 |

16 |

8 |

|

Memory impairment |

7 |

16 |

3 |

|

Abnormal coordination |

7 |

16 |

2 |

|

Disturbance in attention |

9 |

0 |

1 |

|

Sensory disturbance |

4 |

7 |

2 |

|

Hyporeflexia |

4 |

5 |

1 |

|

Paraesthesia |

7 |

2 |

1 |

|

Lethargy |

4 |

7 |

2 |

|

Hyperreflexia |

4 |

2 |

3 |

|

Hypoaesthesia |

4 |

5 |

1 |

|

Sedation |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Status epilepticus |

2 |

5 |

0 |

|

Dysarthria |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

Postictal state |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

Sensory loss |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Psychiatric Disorders | |||

|

Irritability |

7 |

23 |

7 |

|

Depression |

6 |

14 |

3 |

|

Confusional state |

4 |

14 |

1 |

|

Anxiety |

4 |

0 |

3 |

|

Depressed mood |

5 |

0 |

1 |

|

Abnormal thinking |

3 |

7 |

0 |

|

Abnormal behavior |

3 |

5 |

1 |

|

Expressive language disorder |

1 |

7 |

1 |

|

Nervousness |

2 |

5 |

2 |

|

Abnormal dreams |

1 |

5 |

1 |

|

Reproductive System | |||

|

Dysmenorrhea |

9 |

5 |

3 |

|

Erectile dysfunction |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Respiratory and ThoracicDisorders |

|||

|

Pharyngolaryngeal pain |

7 |

14 |

5 |

|

Cough |

2 |

14 |

7 |

|

Pulmonary congestion |

0 |

5 |

1 |

|

Sinus headache |

6 |

2 |

1 |

|

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders |

|||

|

Rash |

4 |

5 |

4 |

Pediatrics 2 to 16 years of age

Table 6 lists adverse reactions from controlled clinical studies of pediatric patients receiving vigabatrin or placebo as adjunctive therapy for refractory complex partial seizures. Adverse reactions that are listed occurred in at least 2% of vigabatrin-treated patients and more frequently than placebo. The median vigabatrin dose was 49.4 mg/kg (range of 8.0 – 105.9 mg/kg).

Table 6. Adverse Reactions in Pooled, Adjunctive Trials in Pediatric Patients 3 to 16 Years of Age with Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

|

Body System Adverse Reaction |

All Vigabatrin [N=165] % |

Placebo [N=104] % |

|

Eye Disorders | ||

|

Diplopia |

3 |

2 |

|

Blurred vision |

2 |

0 |

|

Gastrointestinal Disorders | ||

|

Upper abdominal pain |

4 |

3 |

|

Constipation |

2 |

1 |

|

General Disorders | ||

|

Fatigue |

10 |

7 |

|

Infections and Infestations | ||

|

Upper respiratory tract infection |

15 |

11 |

|

Influenza |

7 |

3 |

|

Otitis media |

6 |

4 |

|

Streptococcal pharyngitis |

4 |

3 |

|

Viral gastroenteritis |

2 |

0 |

|

Investigations | ||

|

15 |

2 |

|

Nervous System Disorders | ||

|

Somnolence |

6 |

5 |

|

Nystagmus |

4 |

3 |

|

Tremor |

4 |

2 |

|

Status epilepticus |

2 |

1 |

|

Psychiatric Disorders | ||

|

Abnormal behavior |

7 |

6 |

|

Aggression |

6 |

2 |

|

Disorientation |

3 |

0 |

Safety of vigabatrin for the treatment of refractory CPS in patients 2 years of age is expected to be similar to pediatric patients 3 to 16 years of age.

Infantile Spasms

In a randomized, placebo-controlled IS study with a 5 day double-blind treatment phase (n=40), the adverse reactions that occurred in >5% of patients receiving vigabatrin and that occurred more frequently than in placebo patients were somnolence (vigabatrin 45%, placebo 30%), bronchitis (vigabatrin 30%, placebo 15%), ear infection (vigabatrin 10%, placebo 5%), and acute otitis media (vigabatrin 10%, placebo 0%).

In a dose response study of low-dose (18-36 mg/kg/day) versus high-dose (100-148 mg/kg/day) vigabatrin, no clear correlation between dose and incidence of adverse reactions was observed. The adverse reactions (≥5% in either dose group) are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7. Adverse Reactions in a Placebo-Controlled Trial in Patients with Infantile Spasm

|

Body System Adverse Reaction |

Vigabatrin Low Dose [N=114] % |

Vigabatrin High Dose [N=108] % |

|

Eye Disorders (other than field or acuity changes) |

||

|

Strabismus |

5 |

5 |

|

Conjunctivitis |

5 |

2 |

|

Gastrointestinal Disorders | ||

|

Vomiting |

14 |

20 |

|

Constipation |

14 |

12 |

|

Diarrhea |

13 |

12 |

|

General Disorders | ||

|

Fever |

29 |

19 |

|

Infections | ||

|

Upper respiratory tract infection |

51 |

46 |

|

Otitis media |

44 |

30 |

|

Viral infection |

20 |

19 |

|

Pneumonia |

13 |

11 |

|

Candidiasis |

8 |

3 |

|

Ear infection |

7 |

14 |

|

Gastroenteritis viral |

6 |

5 |

|

Sinusitis |

5 |

9 |

|

Urinary tract infection |

5 |

6 |

|

Influenza |

5 |

3 |

|

Croup infectious |

5 |

1 |

|

Metabolism & Nutrition Disorders | ||

|

Decreased appetite |

9 |

7 |

|

Nervous System Disorders | ||

|

Sedation |

19 |

17 |

|

Somnolence |

17 |

19 |

|

Status epilepticus |

6 |

4 |

|

Lethargy |

5 |

7 |

|

Convulsion |

4 |

7 |

|

Hypotonia |

4 |

6 |

|

Psychiatric Disorders | ||

|

Irritability |

16 |

23 |

|

Insomnia |

10 |

12 |

|

Respiratory Disorders | ||

|

Nasal congestion |

13 |

4 |

|

Cough |

3 |

8 |

|

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders | ||

|

Rash |

8 |

11 |

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of vigabatrin. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure. Adverse reactions are categorized by system organ class.

Birth Defects: Congenital cardiac defects, congenital external ear anomaly, congenital hemangioma, congenital hydronephrosis, congenital male genital malformation, congenital oral malformation, congenital vesicoureteric reflux, dentofacial anomaly, dysmorphism, fetal anticonvulsant syndrome, hamartomas, hip dysplasia, limb malformation, limb reduction defect, low set ears, renal aplasia, retinitis pigmentosa, supernumerary nipple, talipes

Ear Disorders: Deafness

Endocrine Disorders: Delayed puberty

Gastrointestinal Disorders: Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, esophagitis

General Disorders: Developmental delay, facial edema, malignant hyperthermia, multi-organ failure

Hepatobiliary Disorders: Cholestasis

Nervous System Disorders: Dystonia, encephalopathy, hypertonia, hypotonia, muscle spasticity, myoclonus, optic neuritis, dyskinesia

Psychiatric Disorders: Acute psychosis, apathy, delirium, hypomania, neonatal agitation, psychotic disorder

Respiratory Disorders: Laryngeal edema, pulmonary embolism, respiratory failure, stridor

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: Angioedema, maculo-papular rash, pruritus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), alopecia

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Antiepileptic Drugs

Phenytoin

Although phenytoin dose adjustments are not routinely required, dose adjustment of phenytoin should be considered if clinically indicated, since vigabatrin may cause a moderate reduction in total phenytoin plasma levels [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Clonazepam

Vigabatrin may moderately increase the Cmax of clonazepam resulting in an increase of clonazepam-associated adverse reactions [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Other AEDs

There are no clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions between vigabatrin and either phenobarbital or sodium valproate. Based on population pharmacokinetics, carbamazepine, clorazepate, primidone, and sodium valproate appear to have no effect on plasma concentrations of vigabatrin [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.2 Oral Contraceptives

Vigabatrin is unlikely to affect the efficacy of steroid oral contraceptives [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.3 Drug-Laboratory Test Interactions

Vigabatrin decreases alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) plasma activity in up to 90% of patients. In some patients, these enzymes become undetectable. The suppression of ALT and AST activity by vigabatrin may preclude the use of these markers, especially ALT, to detect early hepatic injury.

Vigabatrin may increase the amount of amino acids in the urine, possibly leading to a false positive test for certain rare genetic metabolic diseases (e.g., alpha aminoadipic aciduria).

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to AEDs, including vigabatrin, during pregnancy. Encourage women who are taking vigabatrin during pregnancy to enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry. This can be done by calling the toll-free number 1-888-233-2334 or visiting the website, http://www.aedpregnancyregistry.org/. This must be done by the patient herself.

Risk Summary

There are no adequate data on the developmental risk associated with the use of vigabatrin in pregnant women. Limited available data from case reports and cohort studies pertaining to vigabatrin use in pregnant women have not established a drug-associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes. However, based on animal data, vigabatrin use in pregnant women may result in fetal harm.

When administered to pregnant animals, vigabatrin produced developmental toxicity, including an increase in fetal malformations and offspring neurobehavioral and neurohistopathological effects, at clinically relevant doses. In addition, developmental neurotoxicity was observed in rats treated with vigabatrin during a period of postnatal development corresponding to the third trimester of human pregnancy (see Data).

In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2-4% and 15-20%, respectively. The background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown.

Data

Animal Data

Administration of vigabatrin (oral doses of 50 to 200 mg/kg/day) to pregnant rabbits throughout the period of organogenesis was associated with an increased incidence of malformations (cleft palate) and embryofetal death; these findings were observed in two separate studies. The no-effect dose for adverse effects on embryofetal development in rabbits (100 mg/kg/day) is approximately 1/2 the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 3 g/day on a body surface area (mg/m2) basis. In rats, oral administration of vigabatrin (50, 100, or 150 mg/kg/day) throughout organogenesis resulted in decreased fetal body weights and increased incidences of fetal anatomic variations. The no-effect dose for adverse effects on embryo-fetal development in rats (50 mg/kg/day) is approximately 1/5 the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. Oral administration of vigabatrin (50, 100, 150 mg/kg/day) to rats from the latter part of pregnancy through weaning produced long-term neurohistopathological (hippocampal vacuolation) and neurobehavioral (convulsions) abnormalities in the offspring. A no-effect dose for developmental neurotoxicity in rats was not established; the low-effect dose (50 mg/kg/day) is approximately 1/5 the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

In a published study, vigabatrin (300 or 450 mg/kg) was administered by intraperitoneal injection to a mutant mouse strain on a single day during organogenesis (day 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, or 12). An increase in fetal malformations (including cleft palate) was observed at both doses.

Oral administration of vigabatrin (5, 15, or 50 mg/kg/day) to young rats during the neonatal and juvenile periods of development (postnatal days 4-65) produced neurobehavioral (convulsions, neuromotor impairment, learning deficits) and neurohistopathological (brain vacuolation, decreased myelination, and retinal dysplasia) abnormalities in treated animals. The early postnatal period in rats is generally thought to correspond to late pregnancy in humans in terms of brain development. The no-effect dose for developmental neurotoxicity in juvenile rats (5 mg/kg/day) was associated with plasma vigabatrin exposures (AUC) less than 1/30 of those measured in pediatric patients receiving an oral dose of 50 mg/kg.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

Vigabatrin is excreted in human milk. The effects of vigabatrin on the breastfed infant and on milk production are unknown. Because of the potential for serious adverse reactions from vigabatrin in nursing infants, breastfeeding is not recommended. If exposing a breastfed infant to vigabatrin, observe for any potential adverse effects [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1, 5.3, 5.4, 5.8)].

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of vigabatrin as adjunctive treatment of refractory complex partial seizures in pediatric patients 2 to 16 years of age have been established and is supported by three double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients 3 to 16 years of age, adequate and well-controlled studies in adult patients, pharmacokinetic data from patients 2 years of age and older, and additional safety information in patients 2 years of age [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3) and Clinical Studies (14.1)]. The dosing recommendation in this population varies according to age group and is weight-based [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)]. Adverse reactions in this pediatric population are similar to those observed in the adult population [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)]. The safety and effectiveness of vigabatrin as monotherapy for pediatric patients with infantile spasms (1 month to 2 years of age) have been established [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Safety and effectiveness as adjunctive treatment of refractory complex partial seizures in pediatric patients below the age of 2 and as monotherapy for the treatment of infantile spasms in pediatric patients below the age of 1 month have not been established.

Duration of therapy for infantile spasms was evaluated in a post hoc analysis of a Canadian Pediatric Epilepsy Network (CPEN) study of developmental outcomes in infantile spasms patients. This analysis suggests that a total duration of 6 months of vigabatrin therapy is adequate for the treatment of infantile spasms. However, prescribers must use their clinical judgment as to the most appropriate duration of use [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Abnormal MRI signal changes and Intramyelinic Edema (IME) in infants and young children being treated with vigabatrin have been observed [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3, 5.4)].

Juvenile Animal Toxicity Data

Oral administration of vigabatrin (5, 15, or 50 mg/kg/day) to young rats during the neonatal and juvenile periods of development (postnatal days 4-65) produced neurobehavioral (convulsions, neuromotor impairment, learning de_cits) and neurohistopathological (brain gray matter vacuolation, decreased myelination, and retinal dysplasia) abnormalities. The no-effect dose for developmental neurotoxicity in juvenile rats (the lowest dose tested) was associated with plasma vigabatrin exposures (AUC) substantially less than those measured in pediatric patients at recommended doses. In dogs, oral administration of vigabatrin (30 or 100 mg/kg/day) during selected periods of juvenile development (postnatal days 22-112) produced neurohistopathological abnormalities (brain gray matter vacuolation). Neurobehavioral effects of vigabatrin were not assessed in the juvenile dog. A no-effect dose for neurohistopathology was not established in juvenile dogs; the lowest effect dose (30 mg/kg/day) was associated with plasma vigabatrin exposures lower than those measured in pediatric patients at recommended doses [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

8.5 Geriatric Use

Clinical studies of vigabatrin did not include sufficient numbers of patients aged 65 and over to determine whether they responded differently from younger patients.

Vigabatrin is known to be substantially excreted by the kidney, and the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, care should be taken in dose selection, and it may be useful to monitor renal function.

Oral administration of a single dose of 1.5 g of vigabatrin to elderly (≥65 years) patients with reduced creatinine clearance (<50 mL/min) was associated with moderate to severe sedation and confusion in 4 of 5 patients, lasting up to 5 days. The renal clearance of vigabatrin was 36% lower in healthy elderly subjects (≥65 years) than in young healthy males. Adjustment of dose or frequency of administration should be considered. Such patients may respond to a lower maintenance dose [see Dosage and Administration (2.4) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients.

8.6 Renal Impairment

Dose adjustment, including initiating treatment with a lower dose, is necessary in pediatric patients 2 years of age and older and adults with mild (creatinine clearance >50 to 80 mL/min), moderate (creatinine clearance >30 to 50 mL/min) and severe (creatinine clearance >10 to 30 mL/min) renal impairment [see Dosage and Administration (2.4) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

Vigabatrin did not produce adverse events or overt behaviors associated with abuse when administered to humans or animals. It is not possible to predict the extent to which a CNS active drug will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, physicians should carefully evaluate patients for history of drug abuse and follow such patients closely, observing them for signs of misuse or abuse of vigabatrin (e.g., incrementation of dose, drug-seeking behavior).

9.3 Dependence

Following chronic administration of vigabatrin to animals, there were no apparent withdrawal signs upon drug discontinuation. However, as with all AEDs, vigabatrin should be withdrawn gradually to minimize increased seizure frequency [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Signs, Symptoms, and Laboratory Findings of Overdosage

Confirmed and/or suspected vigabatrin overdoses have been reported during clinical trials and in post marketing surveillance. No vigabatrin overdoses resulted in death. When reported, the vigabatrin dose ingested ranged from 3 g to 90 g, but most were between 7.5 g and 30 g. Nearly half the cases involved multiple drug ingestions including carbamazepine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, lamotrigine, valproic acid, acetaminophen, and/or chlorpheniramine.

Coma, unconsciousness, and/or drowsiness were described in the majority of cases of vigabatrin overdose. Other less commonly reported symptoms included vertigo, psychosis, apnea or respiratory depression, bradycardia, agitation, irritability, confusion, headache, hypotension, abnormal behavior, increased seizure activity, status epilepticus, and speech disorder. These symptoms resolved with supportive care.

10.2 Management of Overdosage

There is no specific antidote for vigabatrin overdose. Standard measures to remove unabsorbed drug should be used, including elimination by emesis or gastric lavage. Supportive measures should be employed, including monitoring of vital signs and observation of the clinical status of the patient.

In an in vitro study, activated charcoal did not significantly adsorb vigabatrin.

The effectiveness of hemodialysis in the treatment of vigabatrin overdose is unknown. In isolated case reports in renal failure patients receiving therapeutic doses of vigabatrin, hemodialysis reduced vigabatrin plasma concentrations by 40% to 60%.

11 DESCRIPTION

Vigabatrin Tablets, USP are an oral antiepileptic drug and are available as white film-coated 500 mg tablets.

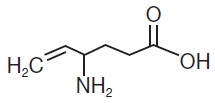

The chemical name of vigabatrin, USP, a racemate consisting of two enantiomers, is (±) 4-amino-5-hexenoic acid. The molecular formula is C6H11NO2 and the molecular weight is 129.16. It has the following structural formula:

Vigabatrin, USP is a white to off-white powder which is freely soluble in water, slightly soluble in methyl alcohol, very slightly soluble in ethyl alcohol and chloroform, and insoluble in toluene and hexane. The pH of a 1% aqueous solution is about 6.9. The n-octanol/water partition coefficient of vigabatrin, USP is about 0.011 (log P=-1.96) at physiologic pH. Vigabatrin, USP melts with decomposition in a 3-degree range within the temperature interval of 171°C to 176°C. The dissociation constants (pKa) of vigabatrin, USP are 4 and 9.7 at room temperature (25°C).

Each Vigabatrin Tablet, USP contains 500 mg of vigabatrin, USP. The inactive ingredients are microcrystalline cellulose, povidone, white coating mixture, sodium starch glycolate and magnesium stearate.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanism of vigabatrin’s anti-seizure effect is unknown, but it is believed to be the result of its action as an irreversible inhibitor of γ-aminobutyric acid transaminase (GABA-T), the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. This action results in increased levels of GABA in the central nervous system.

No direct correlation between plasma concentration and efficacy has been established. The duration of drug effect is presumed to be dependent on the rate of enzyme re-synthesis rather than on the rate of elimination of the drug from the systemic circulation.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

Effects on Electrocardiogram

There is no indication of a QT/QTc prolonging effect of vigabatrin in single doses up to 6.0 g. In a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study, 58 healthy subjects were administered a single oral dose of vigabatrin (3 g and 6 g) and placebo. Peak concentrations for 6.0 g vigabatrin were approximately 2-fold higher than the peak concentrations following the 3.0 g single oral dose.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Vigabatrin displayed linear pharmacokinetics after administration of single doses ranging from 0.5 g to 4 g, and after administration of repeated doses of 0.5 g and 2.0 g twice daily. Bioequivalence has been established between the oral solution and tablet formulations. The following PK information (Tmax, half-life, and clearance) of vigabatrin was obtained from stand-alone PK studies and population PK analyses.

Absorption

Following oral administration, vigabatrin is essentially completely absorbed. The time to maximum concentration (Tmax) is approximately 1 hour for children and adolescents (3 years to 16 years of age) and adults, and approximately 2.5 hours for infants (5 months to 2 years of age). There was little accumulation with multiple dosing in adult and pediatric patients. A food effect study involving administration of vigabatrin to healthy volunteers under fasting and fed conditions indicated that the Cmax was decreased by 33%, Tmax was increased to 2 hours, and AUC was unchanged under fed conditions.

Distribution

Vigabatrin does not bind to plasma proteins. Vigabatrin is widely distributed throughout the body; mean steady-state volume of distribution is 1.1 L/kg (CV = 20%).

Metabolism and Elimination

Vigabatrin is not significantly metabolized; it is eliminated primarily through renal excretion. The terminal half-life of vigabatrin is about 5.7 hours for infants (5 months to 2 years of age), 6.8 hours for children (3 to 9 years of age), 9.5 hours for children and adolescents (10 to 16 years of age), and 10.5 hours for adults. Following administration of [14]C-vigabatrin to healthy male volunteers, about 95% of total radioactivity was recovered in the urine over 72 hours with the parent drug representing about 80% of this. Vigabatrin induces CYP2C9, but does not induce other hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme systems.

Specific Populations

Geriatric

The renal clearance of vigabatrin in healthy elderly patients (≥65 years of age) was 36% less than those in healthy younger patients. This finding is confirmed by an analysis of data from a controlled clinical trial [see Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

Pediatric

The clearance of vigabatrin is 2.4 L/hr for infants (5 months to 2 years of age), 5.1 L/hr for children (3 to 9 years of age), 5.8 L/hr for children and adolescents (10 to 16 years of age) and 7 L/hr for adults.

Gender

No gender differences were observed for the pharmacokinetic parameters of vigabatrin in patients.

Race

No specific study was conducted to investigate the effects of race on vigabatrin pharmacokinetics. A cross study comparison between 23 Caucasian and 7 Japanese patients who received 1, 2, and 4 g of vigabatrin indicated that the AUC, Cmax, and half-life were similar for the two populations. However, the mean renal clearance of Caucasians (5.2 L/hr) was about 25% higher than the Japanese (4.0 L/hr). Inter-subject variability in renal clearance was 20% in Caucasians and was 30% in Japanese.

Renal Impairment

Mean AUC increased by 30% and the terminal half-life increased by 55% (8.1 hr vs 12.5 hr) in adult patients with mild renal impairment (CLcr from >50 to 80 mL/min) in comparison to normal subjects. Mean AUC increased by two-fold and the terminal half-life increased by two-fold in adult patients with moderate renal impairment (CLcr from >30 to 50 mL/min) in comparison to normal subjects. Mean AUC increased by 4.5-fold and the terminal half-life increased by 3.5-fold in adult patients with severe renal impairment (CLcr from >10 to 30 mL/min) in comparison to normal subjects.

Adult patients with renal impairment

Dosage adjustment, including starting at a lower dose, is recommended for adult patients with any degree of renal impairment [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6) and Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

Infants with renal impairment

Information about how to adjust the dose in infants with renal impairment is unavailable.

Pediatric patients 2 years and older with renal impairment

Although information is unavailable on the effects of renal impairment on vigabatrin clearance in pediatric patients 2 years and older, dosing can be calculated based upon adult data and an established formula [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6) and Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

Hepatic Impairment

Vigabatrin is not significantly metabolized. The pharmacokinetics of vigabatrin in patients with impaired liver function has not been studied.

Drug Interactions

Phenytoin

A 16% to 20% average reduction in total phenytoin plasma levels was reported in adult controlled clinical studies. In vitro drug metabolism studies indicate that decreased phenytoin concentrations upon addition of vigabatrin therapy are likely to be the result of induction of cytochrome P450 2C enzymes in some patients. Although phenytoin dose adjustments are not routinely required, dose adjustment of phenytoin should be considered if clinically indicated [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Clonazepam

In a study of 12 healthy adult volunteers, clonazepam (0.5 mg) co-administration had no effect on vigabatrin (1.5 g twice daily) concentrations. Vigabatrin increases the mean Cmax of clonazepam by 30% and decreases the mean Tmax by 45% [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Other AEDs

When co-administered with vigabatrin, phenobarbital concentration (from phenobarbital or primidone) was reduced by an average of 8% to 16%, and sodium valproate plasma concentrations were reduced by an average of 8%. These reductions did not appear to be clinically relevant. Based on population pharmacokinetics, carbamazepine, clorazepate, primidone, and sodium valproate appear to have no effect on plasma concentrations of vigabatrin [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Alcohol

Co-administration of ethanol (0.6 g/kg) with vigabatrin (1.5 g twice daily) indicated that neither drug influences the pharmacokinetics of the other.

Oral Contraceptives

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study using a combination oral contraceptive containing 30 mcg ethinyl estradiol and 150 mcg levonorgestrel, vigabatrin (3 g/day) did not interfere significantly with the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme (CYP3A)-mediated metabolism of the contraceptive tested. Based on this study, vigabatrin is unlikely to affect the efficacy of steroid oral contraceptives. Additionally, no significant difference in pharmacokinetic parameters (elimination half-life, AUC, Cmax, apparent oral clearance, time to peak, and apparent volume of distribution) of vigabatrin were found after treatment with ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel [see Drug Interactions (7.2)].

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Vigabatrin showed no carcinogenic potential in mouse or rat when given in the diet at doses up to 150 mg/kg/day for 18 months (mouse) or at doses up to 150 mg/kg/day for 2 years (rat). These doses are less than the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) for infantile spasms (150 mg/kg/day) and for refractory complex partial seizures (3 g/day) on a mg/m2 basis.

Vigabatrin was negative in in vitro (Ames, CHO/HGPRT mammalian cell forward gene mutation, chromosomal aberration in rat lymphocytes) and in in vivo (mouse bone marrow micronucleus) assays.

No adverse effects on male or female fertility were observed in rats at oral doses up to 150 mg/kg/day (approximately 1/2 the MRHD of 3 g/day on a mg/m2 basis for refractory complex partial seizures).

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Complex Partial Seizures

Adults

The effectiveness of vigabatrin as adjunctive therapy in adult patients was established in two U.S. multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical studies. A total of 357 adults (age 18 to 60 years) with complex partial seizures, with or without secondary generalization were enrolled (Studies 1 and 2). Patients were required to be on an adequate and stable dose of an anticonvulsant, and have a history of failure on an adequate regimen of carbamazepine or phenytoin. Patients had a history of about 8 seizures per month (median) for about 20 years (median) prior to entrance into the study. These studies were not capable by design of demonstrating direct superiority of vigabatrin over any other anticonvulsant added to a regimen to which the patient had not adequately responded. Further, in these studies, patients had previously been treated with a limited range of anticonvulsants.

The primary measure of efficacy was the patient’s reduction in mean monthly frequency of complex partial seizures plus partial seizures secondarily generalized at end of study compared to baseline.

Study 1

Study 1 (N=174) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study consisting of an 8-week baseline period followed by an 18-week treatment period. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 1, 3, or 6 g/day vigabatrin administered twice daily. During the first 6 weeks following randomization, the dose was titrated upward beginning with 1 g/day and increasing by 0.5 g/day on days 1 and 5 of each subsequent week in the 3 g/day and 6 g/day groups, until the assigned dose was reached.

Results for the primary measure of effectiveness, reduction in monthly frequency of complex partial seizures, are shown in Table 8. The 3 g/day and 6 g/day dose groups were statistically significantly superior to placebo, but the 6 g/day dose was not superior to the 3 g/day dose.

Table 8. Median Monthly Frequency of Complex Partial Seizures+

|

N |

Baseline |

Endstudy |

|

|

Placebo |

45 |

9.0 |

8.8 |

|

1 g/day vigabatrin |

45 |

8.5 |

7.7 |

|

3 g/day vigabatrin |

41 |

8.5 |

3.7* |

|

6 g/day vigabatrin |

43 |

8.5 |

4.5* |

*p<0.05 compared to placebo

+Including one patient with simple partial seizures with secondary generalization only

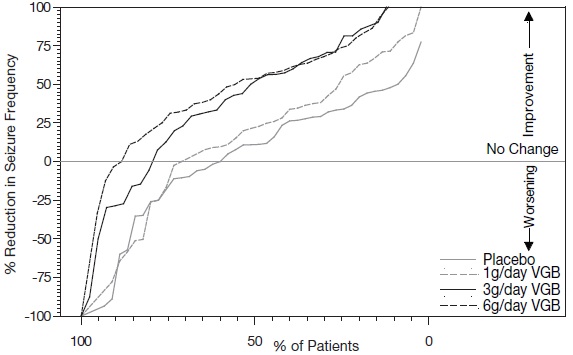

Figure 1 presents the percentage of patients (X-axis) with a percent reduction in seizure frequency (responder rate) from baseline to the maintenance phase at least as great as that represented on the Y-axis. A positive value on the Y-axis indicates an improvement from baseline (i.e., a decrease in complex partial seizure frequency), while a negative value indicates a worsening from baseline (i.e., an increase in complex partial seizure frequency). Thus, in a display of this type, a curve for an effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for placebo. The proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in complex partial seizure frequency was consistently higher for the vigabatrin 3 and 6 g/day groups compared to the placebo group. For example, 51% of patients randomized to vigabatrin 3 g/day and 53% of patients randomized to vigabatrin 6 g/day experienced a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency, compared to 9% of patients randomized to placebo. Patients with an increase in seizure frequency >100% are represented on the Y-axis as equal to or greater than -100%.

Figure 1. Percent Reduction from Baseline in Seizure Frequency

Study 2

Study 2 (N=183 randomized, 182 evaluated for efficacy) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study consisting of an 8-week baseline period and a 16-week treatment period. During the first 4 weeks following randomization, the dose of vigabatrin was titrated upward beginning with 1 g/day and increased by 0.5 g/day on a weekly basis to the maintenance dose of 3 g/day.

Results for the primary measure of effectiveness, reduction in monthly complex partial seizure frequency, are shown in Table 9. Vigabatrin 3 g/day was statistically significantly superior to placebo in reducing seizure frequency.

Table 9. Median Monthly Frequency of Complex Partial Seizures

|

N |

Baseline |

Endstudy |

|

|

Placebo |

90 |

9.0 |

7.5 |

|

3 g/day vigabatrin |

92 |

8.3 |

5.5* |

*p<0.05 compared to placebo

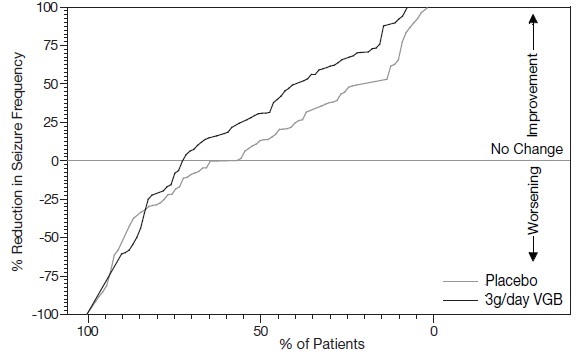

Figure 2 presents the percentage of patients (X-axis) with a percent reduction in seizure frequency (responder rate) from baseline to the maintenance phase at least as great as that represented on the Y-axis. A positive value on the Y-axis indicates an improvement from baseline (i.e., a decrease in complex partial seizure frequency), while a negative value indicates a worsening from baseline (i.e., an increase in complex partial seizure frequency). Thus, in a display of this type, a curve for an effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for placebo. The proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in seizure frequency was consistently higher for the vigabatrin 3 g/day group compared to the placebo group. For example, 39% of patients randomized to vigabatrin (3 g/day) experienced a 50% or greater reduction in complex partial seizure frequency, compared to 21% of patients randomized to placebo. Patients with an increase in seizure frequency >100% are represented on the Y-axis as equal to or greater than -100%.

Figure 2. Percent Reduction from Baseline in Seizure Frequency

For both studies, there was no difference in the effectiveness of vigabatrin between male and female patients. Analyses of age and race were not possible as nearly all patients were between the ages of 18 to 65 and Caucasian.

Pediatric patients 3 to 16 years of age