GABAZOLAMINE- alprazolam, choline kit

Gabazolamine by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Gabazolamine by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Physician Therapeutics LLC, Actavis Elizabeth LLC, H.J. Harkins Company, Inc, Targeted Medical Pharma Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

DESCRIPTION

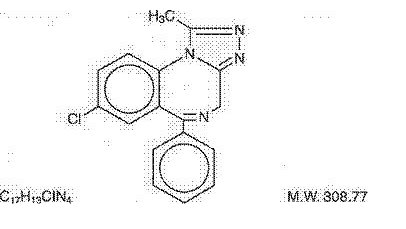

Alprazolam is a triazolo analog of the 1,4 benzodiazepine class of central nervous system-active compounds.

The chemical name of alprazolam is 8-chloro-1-methyl-6-phenyl-4H-s-triazolo [4,3-α] [1,4] benzodiazepine, and its structural formula is:

Alprazolam is a white to off-white crystalline powder, which is soluble in alcohol but which has no appreciable solubility in water at physiological pH.

Each tablet, for oral administration, contains 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, 1 mg, and 2 mg of alprazolam. The 2 mg tablets are multiscored, and may be divided in half to provide two 1 mg segments, or quarters to provide four 0.5 mg segments.

In addition, each tablet contains the following inactive ingredients: colloidal silicon dioxide, corn starch, docusate sodium, lactose (hydrous), magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, and sodium benzoate. The 0.5 mg tablet also contains FD C yellow #6 aluminum lake (sunset yellow lake). The 1 mg tablet also contains FD C blue #2 aluminum lake. The 2 mg tablet also contains D C yellow #10 aluminum lake.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

CNS agents of the 1,4 benzodiazepine class presumably exert their effects by binding at stereo specific receptors at several sites within the central nervous system. Their exact mechanism of action is unknown. Clinically, all benzodiazepines cause a dose-related central nervous system depressant activity varying from mild impairment of task performance to hypnosis.

Following oral administration, alprazolam is readily absorbed. Peak concentrations in the plasma occur in one to two hours following administration. Plasma levels are proportionate to the dose given; over the dose range of 0.5 to 3 mg, peak levels of 8.0 to 37 ng/mL were observed. Using a specific assay methodology, the mean plasma elimination half-life of alprazolam has been found to be about 11.2 hours (range: 6.3 to 26.9 hours) in healthy adults.

The predominant metabolites are α -hydroxy-alprazolam and a benzophenone derived from alprazolam. The biological activity of α -hydroxy-alprazolam is approximately one-half that of alprazolam. The benzophenone metabolite is essentially inactive. Plasma levels of these metabolites are extremely low, thus precluding precise pharmacokinetic description. However, their half-lives appear to be of the same order of magnitude as that of alprazolam. Alprazolam and its metabolites are excreted primarily in the urine.

The ability of alprazolam to induce human hepatic enzyme systems has not yet been determined. However, this is not a property of benzodiazepines in general. Further, alprazolam did not affect the prothrombin or plasma warfarin levels in male volunteers administered sodium warfarin orally.

In vitro, alprazolam is bound (80 percent) to human serum protein.

Changes in the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of benzodiazepines have been reported in a variety of disease states including alcoholism, impaired hepatic function and impaired renal function. Changes have also been demonstrated in geriatric patients. A mean half-life of alprazolam of 16.3 hours has been observed in healthy elderly subjects (range: 9.0 to 26.9 hours, n=16) compared to 11.0 hours (range: 6.3 to 15.8 hours, n=16) in healthy adult subjects. In patients with alcoholic liver disease the half-life of alprazolam ranged between 5.8 and 65.3 hours (mean: 19.7 hours, n=17) as compared to between 6.3 and 26.9 hours (mean=11.4 hours, n=17) in healthy subjects. In an obese group of subjects the half-life of alprazolam ranged between 9.9 and 40.4 hours (mean=21.8 hours, n=12) as compared to between 6.3 and 15.8 hours (mean=10.6 hours, n=12) in healthy subjects.

Because of its similarity to other benzodiazepines, it is assumed that alprazolam undergoes transplacental passage and that it is excreted in human milk.

-

INDICATIONS & USAGE

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Alprazolam tablets are indicated for the management of anxiety disorder (a condition corresponding most closely to the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III-R) diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder) or the short-term relief of symptoms of anxiety. Anxiety or tension associated with the stress of everyday life usually does not require treatment with an anxiolytic.

Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by unrealistic or excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation) about two or more life circumstances, for a period of six months or longer, during which the person has been bothered more days than not by these concerns. At least 6 of the following 18 symptoms are often present in these patients: Motor Tension (trembling, twitching, or feeling shaky; muscle tension, aches, or soreness; restlessness; easy fatigability); Autonomic Hyperactivity (shortness of breath or smothering sensations; palpitations or accelerated heart rate; sweating, or cold clammy hands; dry mouth; dizziness or light-headedness; nausea, diarrhea, or other abdominal distress; flushes or chills; frequent urination; trouble swallowing or ‘lump in throat’); Vigilance and Scanning (feeling keyed up or on edge; exaggerated startle response; difficulty concentrating or ‘mind going blank’ because of anxiety; trouble falling or staying asleep; irritability). These symptoms must not be secondary to another psychiatric disorder or caused by some organic factor.

Anxiety associated with depression is responsive to alprazolam.

Alprazolam tablets are also indicated for the treatment of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

Studies supporting this claim were conducted in patients whose diagnoses corresponded closely to the DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder (see CLINICAL STUDIES).

Panic disorder is an illness characterized by recurrent panic attacks. The panic attacks, at least initially, are unexpected. Later in the course of this disturbance certain situations, eg, driving a car or being in a crowded place, may become associated with having a panic attack. These panic attacks are not triggered by situations in which the person is the focus of others’ attention (as in social phobia). The diagnosis requires four such attacks within a four week period, or one or more attacks followed by at least a month of persistent fear of having another attack. The panic attacks must be characterized by at least four of the following symptoms: dyspnea or smothering sensations; dizziness, unsteady feelings, or faintness; palpitations or tachycardia; trembling or shaking; sweating; choking; nausea or abdominal distress; depersonalization or derealization; paresthesias; hot flashes or chills; chest pain or discomfort; fear of dying; fear of going crazy or of doing something uncontrolled. At least some of the panic attack symptoms must develop suddenly, and the panic attack symptoms must not be attributed to some know organic factors. Panic disorder is frequently associated with some symptoms of agoraphobia.

Demonstrations of the effectiveness of alprazolam by systematic clinical study are limited to four months duration for anxiety disorder and four to ten weeks duration for panic disorder; however, patients with panic disorder have been treated on an open basis for up to eight months without apparent loss of benefit. The physician should periodically reassess the usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Alprazolam tablets are contraindicated in patients with known sensitivity to this drug or other benzodiazepines. Alprazolam may be used in patients with open angle glaucoma who are receiving appropriate therapy, but is contraindicated in patients with acute narrow angle glaucoma.

Alprazolam is contraindicated with ketoconazole and intraconazole, since these medications significantly impair the oxidative metabolism mediated by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP 3A) (see WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions).

-

WARNINGS

WARNINGSDependence And Withdrawal Reactions, Including Seizures:

Certain adverse clinical events, some life-threatening, are a direct consequence of physical dependence to alprazolam. These include a spectrum of withdrawal symptoms; the most important is seizure (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE). Even after relatively short-term use at the doses recommended for the treatment of transient anxiety and anxiety disorder (ie, 0.75 to 4 mg per day), there is some risk of dependence. Spontaneous reporting system data suggest that the risk of dependence and its severity appear to be greater in patients treated with doses greater than 4 mg/day and for long periods (more than 12 weeks). However, in a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients, the duration of treatment (three months compared to six months) had no effect on the ability of patients to taper to zero dose. In contrast, patients treated with doses of alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day had more difficulty tapering to zero dose than those treated with less than 4 mg/day.

The Importance Of Dose And The Risks Of Alprazolam As A Treatment For Panic Disorder: Because the management of panic disorder often requires the use of average daily doses of alprazolam above 4 mg, the risk of dependence among panic disorder patients may be higher than that among those treated for less severe anxiety. Experience in randomized placebo-controlled discontinuation studies of patients with panic disorder showed a high rate of rebound and withdrawal symptoms in patients treated with alprazolam compared to placebo treated patients.

Relapse or return of illness was defined as a return of symptoms characteristic of panic disorder (primarily panic attacks) to levels approximately equal to those seen at baseline before active treatment was initiated. Rebound refers to a return of symptoms of panic disorder to a level substantially greater in frequency, or more severe in intensity than seen at baseline. Withdrawal symptoms were identified as those which were generally not characteristic of panic disorder and which occurred for the first time more frequently during discontinuation than at baseline.

In a controlled clinical trial in which 63 patients were randomized to alprazolam and where withdrawal symptoms were specifically sought, the following were identified as symptoms of withdrawal: heightened sensory perception, impaired concentration, dysosmia, clouded sensorium, paresthesias, muscle cramps, muscle twitch, diarrhea, blurred vision, appetite decrease and weight loss. Other symptoms, such as anxiety and insomnia, were frequently seen during discontinuation, but it could not be determined if they were due to return of illness, rebound or withdrawal.

In a larger database comprised of both controlled and uncontrolled studies in which 641 patients received alprazolam, discontinuation-emergent symptoms which occurred at a rate of over 5% in patients treated with alprazolam and at a greater rate than the placebo treated group were as follows:

DISCONTINUATION-EMERGENT SYMPTOM INCIDENCE

Percentage of 641 Alprazolam-Treated Panic Disorder Patients Reporting Events

Body System/Event

Neurologic

Gastrointestinal

Insomnia 29.5 Nausea/Vomiting 16.5 Light-headedness 19.3 Diarrhea 13.6 Abnormal involuntary movement 17.3 Decreased salivation 10.6 Headache 17.0 Metabolic-Nutritional

Muscular twitching 6.9 Weight loss 13.3 Impaired coordination 6.6 Decreased appetite 12.8 Muscle tone disorders 5.9

Weakness 5.8 Dermatological

Psychiatric

Sweating 14.4 Anxiety 19.2

Fatigue and Tiredness 18.4 Cardiovascular

Irritability 10.5 Tachycardia 12.2 Cognitive disorder 10.3

Memory impairment 5.5 Special Senses

Depression 5.1 Blurred vision 10.0 Confusional state 5.0

From the studies cited, it has not been determined whether these symptoms are clearly related to the dose and duration of therapy with alprazolam in patients with panic disorder.

In two controlled trials of six to eight weeks duration where the ability of patients to discontinue medication was measured, 71%-93% of alprazolam treated patients tapered completely off therapy compared to 89%-96% of placebo treated patients. In a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients, the duration of treatment (three months compared to six months) had no effect on the ability of patients to taper to zero dose.

Seizures attributable to alprazolam were seen after drug discontinuance or dose reduction in 8 of 1980 patients with panic disorder or in patients participating in clinical trials where doses of alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day for over 3 months were permitted. Five of these cases clearly occurred during abrupt dose reduction, or discontinuation from daily doses of 2 to 10 mg. Three cases occurred in situations where there was not a clear relationship to abrupt dose reduction or discontinuation. In one instance, seizure occurred after discontinuation from a single dose of 1 mg after tapering at a rate of 1 mg every three days from 6 mg daily. In two other instances, the relationship to taper is indeterminate; in both of these cases the patients had been receiving doses of 3 mg daily prior to seizure. The duration of use in the above 8 cases ranged from 4 to 22 weeks. There have been occasional voluntary reports of patients developing seizures while apparently tapering gradually from alprazolam. The risk of seizure seems to be greatest 24-72 hours after discontinuation (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION for recommended tapering and discontinuation schedule).

Status Epilepticus And Its Treatment:The medical event voluntary reporting system shows that withdrawal seizures have been reported in association with the discontinuation of alprazolam. In most cases, only a single seizure was reported; however, multiple seizures and status epilepticus were reported as well. Ordinarily, the treatment of status epilepticus of any etiology involves use of intravenous benzodiazepines plus phenytoin or barbiturates, maintenance of a patent airway and adequate hydration. For additional details regarding therapy, consultation with an appropriate specialist may be considered.

Interdose Symptoms:Early morning anxiety and emergence of anxiety symptoms between doses of alprazolam have been reported in patients with panic disorder taking prescribed maintenance doses of alprazolam. These symptoms may reflect the development of tolerance or a time interval between doses which is longer than the duration of clinical action of the administered dose. In either case, it is presumed that the prescribed dose is not sufficient to maintain plasma levels above those needed to prevent relapse, rebound or withdrawal symptoms over the entire course of the interdosing interval. In these situations, it is recommended that the same total daily dose be given divided as more frequent administrations (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Risk Of Dose Reduction:Withdrawal reactions may occur when dosage reduction occurs for any reason. This includes purposeful tapering, but also inadvertent reduction of dose (eg, the patient forgets, the patient is admitted to a hospital, etc.). Therefore, the dosage of alprazolam should be reduced or discontinued gradually (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Alprazolam is not of value in the treatment of psychotic patients and should not be employed in lieu of appropriate treatment for psychosis. Because of its CNS depressant effects, patients receiving alprazolam should be cautioned against engaging in hazardous occupations or activities requiring complete mental alertness such as operating machinery or driving a motor vehicle. For the same reason, patients should be cautioned about the simultaneous ingestion of alcohol and other CNS depressant drugs during treatment with alprazolam.

Benzodiazepines can potentially cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women. If alprazolam is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus. Because of experience with other members of the benzodiazepine class, alprazolam is assumed to be capable of causing an increased risk of congenital abnormalities when administered to a pregnant woman during the first trimester. Because use of these drugs is rarely a matter of urgency, their use during the first trimester should almost always be avoided. The possibility that a woman of childbearing potential may be pregnant at the time of institution of therapy should be considered. Patients should be advised that if they become pregnant during therapy or intend to become pregnant they should communicate with their physicians about the desirability of discontinuing the drug.

Alprazolam Interaction With Drugs That Inhibit Metabolism Via Cytochrome P4503A:The initial step in alprazolam metabolism is hydroxylation catalyzed by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP 3A). Drugs that inhibit this metabolic pathway may have a profound effect on the clearance of alprazolam. Consequently, alprazolam should be avoided in patients receiving very potent inhibitors of CYP 3A. With drugs inhibiting CYP 3A to a lesser but still significant degree, alprazolam should be used only with caution and consideration of appropriate dosage reduction. For some drugs, an interaction with alprazolam has been quantified with clinical data; for other drugs, interactions are predicted from in vitro data and/or experience with similar drugs in the same pharmacologic class.

The following are examples of drugs known to inhibit the metabolism of alprazolam and/or related benzodiazepines, presumably through inhibition of CYP 3A.

Potent CYP 3A Inhibitors:Azole antifungal agents--Although in vivo interaction data with alprazolam are not available, ketoconazole and intraconazole are potent CYP 3A inhibitors and the coadministration of alprazolam with them is not recommended. Other azole-type antifungal agents should also be considered potent CYP 3A inhibitors and the coadministration of alprazolam with them is not recommended (see CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Drugs Demonstrated To Be CYP 3A Inhibitors On The Basis Of Clinical Studies Involving Alprazolam (Caution And Consideration Of Appropriate Alprazolam Dose Reduction Are Recommended Dduring Coadministration With The Following Drugs):

Nefazodone--Coadministration of nefazodone increased alprazolam concentration two-fold.

Fluvoxamine--Coadministration of fluvoxamine approximately doubled the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam, decreased clearance by 49%, increased half-life by 71%, and decreased measured psychomotor performance.

Cimetidine--Coadministration of cimetidine increased the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam by 86%, decreased clearance by 42%, and increased half-life by 16%.

Other Drugs Possibly Affecting Alprazolam Metabolism:Other drugs possibly affecting alprazolam metabolism by inhibition of CYP 3A are discussed in the PRECAUTIONS section (see PRECAUTIONS-Drug Interactions).

-

PRECAUTIONS

PRECAUTIONSGeneral

If alprazolam is to be combined with other psychotropic agents or anticonvulsant drugs, careful consideration should be given to the pharmacology of the agents to be employed, particularly with compounds which might potentiate the action of benzodiazepines (see Drug Interactions).

As with other psychotropic medications, the usual precautions with respect to administration of the drug and size of the prescription are indicated for severely depressed patients or those in whom there is reason to expect concealed suicidal ideation or plans.

It is recommended that the dosage be limited to the smallest effective dose to preclude the development of ataxia or oversedation which may be a particular problem in elderly or debilitated patients. (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). The usual precautions in treating patients with impaired renal, hepatic or pulmonary function should be observed. There have been rare reports of death in patients with severe pulmonary disease shortly after the initiation of treatment with alprazolam. A decreased systemic alprazolam elimination rate (eg, increased plasma half-life) has been observed in both alcoholic liver disease patients and obese patients receiving alprazolam (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

Episodes of hypomania and mania have been reported in association with the use of alprazolam in patients with depression.

Alprazolam has a weak uricosuric effect. Although other medications with weak uricosuric effect have been reported to cause acute renal failure, there have been no reported instances of acute renal failure attributable to therapy with alprazolam.

-

INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS

WARNINGS Dependence and Withdrawal Reactions, Including Seizures Certain adverse clinical events, some life-threatening, are a direct consequence of physical dependence to Alprazolam. These include a spectrum of withdrawal symptoms; the most important is seizure (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE). Even after relatively short-term use at the doses recommended for the treatment of transient anxiety and anxiety disorder (ie, 0.75 to 4.0 mg per day), there is some risk of dependence. Spontaneous reporting system data suggest that the risk of dependence and its severity appear to be greater in patients treated with doses greater than 4 mg/day and for long periods (more than 12 weeks). However, in a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients, the duration of treatment (3 months compared to 6 months) had no effect on the ability of patients to taper to zero dose. In contrast, patients treated with doses of Alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day had more difficulty tapering to zero dose than those treated with less than 4 mg/day. The importance of dose and the risks of Alprazolam as a treatment for panic disorder Because the management of panic disorder often requires the use of average daily doses of Alprazolam above 4 mg, the risk of dependence among panic disorder patients may be higher than that among those treated for less severe anxiety. Experience in randomized placebo-controlled discontinuation studies of patients with panic disorder showed a high rate of rebound and withdrawal symptoms in patients treated with Alprazolam compared to placebo-treated patients. Relapse or return of illness was defined as a return of symptoms characteristic of panic disorder (primarily panic attacks) to levels approximately equal to those seen at baseline before active treatment was initiated. Rebound refers to a return of symptoms of panic disorder to a level substantially greater in frequency, or more severe in intensity than seen at baseline. Withdrawal symptoms were identified as those which were generally not characteristic of panic disorder and which occurred for the first time more frequently during discontinuation than at baseline. In a controlled clinical trial in which 63 patients were randomized to Alprazolam and where withdrawal symptoms were specifically sought, the following were identified as symptoms of withdrawal: heightened sensory perception, impaired concentration, dysosmia, clouded sensorium, paresthesias, muscle cramps, muscle twitch, diarrhea, blurred vision, appetite decrease, and weight loss. Other symptoms, such as anxiety and insomnia, were frequently seen during discontinuation, but it could not be determined if they were due to return of illness, rebound, or withdrawal.

In two controlled trials of 6 to 8 weeks duration where the ability of patients to discontinue medication was measured, 71%–93% of patients treated with Alprazolam tapered completely off therapy compared to 89%–96% of placebo-treated patients. In a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients, the duration of treatment (3 months compared to 6 months) had no effect on the ability of patients to taper to zero dose. Seizures attributable to Alprazolam were seen after drug discontinuance or dose reduction in 8 of 1980 patients with panic disorder or in patients participating in clinical trials where doses of Alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day for over 3 months were permitted.

Five of these cases clearly occurred during abrupt dose reduction, or discontinuation from daily doses of 2 to 10 mg. Three cases occurred in situations where there was not a clear relationship to abrupt dose reduction or discontinuation. In one instance, seizure occurred after discontinuation from a single dose of 1 mg after tapering at a rate of 1 mg every 3 days from 6 mg daily. In two other instances, the relationship to taper is indeterminate; in both of these cases the patients had been receiving doses of 3 mg daily prior to seizure. The duration of use in the above 8 cases ranged from 4 to 22 weeks. There have been occasional voluntary reports of patients developing seizures while apparently tapering gradually from Alprazolam. The risk of seizure seems to be greatest 24–72 hours after discontinuation (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION for recommended tapering and discontinuation schedule).

Status Epilepticus and its Treatment The medical event voluntary reporting system shows that withdrawal seizures have been reported in association with the discontinuation of Alprazolam. In most cases, only a single seizure was reported; however, multiple seizures and status epilepticus were reported as well. Interdose Symptoms Early morning anxiety and emergence of anxiety symptoms between doses of Alprazolam have been reported in patients with panic disorder taking prescribed maintenance doses of Alprazolam. These symptoms may reflect the development of tolerance or a time interval between doses which is longer than the duration of clinical action of the administered dose. In either case, it is presumed that the prescribed dose is not sufficient to maintain plasma levels above those needed to prevent relapse, rebound or withdrawal symptoms over the entire course of the interdosing interval. In these situations, it is recommended that the same total daily dose be given divided as more frequent administrations (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Risk of Dose Reduction Withdrawal reactions may occur when dosage reduction occurs for any reason. This includes purposeful tapering, but also inadvertent reduction of dose (eg, the patient forgets, the patient is admitted to a hospital). Therefore, the dosage of Alprazolam should be reduced or discontinued gradually (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). CNS Depression and Impaired Performance Because of its CNS depressant effects, patients receiving Alprazolam should be cautioned against engaging in hazardous occupations or activities requiring complete mental alertness such as operating machinery or driving a motor vehicle. For the same reason, patients should be cautioned about the simultaneous ingestion of alcohol and other CNS depressant drugs during treatment with Alprazolam. Risk of Fetal Harm Benzodiazepines can potentially cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women.

If Alprazolam is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus. Because of experience with other members of the benzodiazepine class, Alprazolam is assumed to be capable of causing an increased risk of congenital abnormalities when administered to a pregnant woman during the first trimester. Because use of these drugs is rarely a matter of urgency, their use during the first trimester should almost always be avoided. The possibility that a woman of childbearing potential may be pregnant at the time of institution of therapy should be considered. Patients should be advised that if they become pregnant during therapy or intend to become pregnant they should communicate with their physicians about the desirability of discontinuing the drug. Alprazolam Interaction with Drugs that Inhibit Metabolism via Cytochrome P4503A The initial step in alprazolam metabolism is hydroxylation catalyzed by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A). Drugs that inhibit this metabolic pathway may have a profound effect on the clearance of alprazolam. Consequently, alprazolam should be avoided in patients receiving very potent inhibitors of CYP3A. With drugs inhibiting CYP3A to a lesser but still significant degree, alprazolam should be used only with caution and consideration of appropriate dosage reduction. For some drugs, an interaction with alprazolam has been quantified with clinical data; for other drugs, interactions are predicted from in vitro data and/or experience with similar drugs in the same pharmacologic class.

The following are examples of drugs known to inhibit the metabolism of alprazolam and/or related benzodiazepines, presumably through inhibition of CYP3A. Potent CYP3A Inhibitors Azole antifungal agents— Ketoconazole and itraconazole are potent CYP3A inhibitors and have been shown in vivo to increase plasma alprazolam concentrations 3.98 fold and 2.70 fold, respectively. The coadministration of alprazolam with these agents is not recommended. Other azole-type antifungal agents should also be considered potent CYP3A inhibitors and the coadministration of alprazolam with them is not recommended (see CONTRAINDICATIONS). Drugs demonstrated to be CYP 3A inhibitors on the basis of clinical studies involving alprazolam (caution and consideration of appropriate alprazolam dose reduction are recommended during coadministration with the following drugs) Nefazodone Coadministration of nefazodone increased alprazolam concentration two-fold. Fluvoxamine Coadministration of fluvoxamine approximately doubled the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam, decreased clearance by 49%, increased half-life by 71%, and decreased measured psychomotor performance. Cimetidine Coadministration of cimetidine increased the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam by 86%, decreased clearance by 42%, and increased half-life by 16%. Other drugs possibly affecting alprazolam metabolism Other drugs possibly affecting alprazolam metabolism by inhibition of CYP3A are discussed in the PRECAUTIONS section (see PRECAUTIONS–Drug Interactions).

-

PRECAUTIONS

PRECAUTIONS

General Suicide As with other psychotropic medications, the usual precautions with respect to administration of the drug and size of the prescription are indicated for severely depressed patients or those in whom there is reason to expect concealed suicidal ideation or plans. Panic disorder has been associated with primary and secondary major depressive disorders and increased reports of suicide among untreated patients. Mania Episodes of hypomania and mania have been reported in association with the use of Alprazolam in patients with depression. Uricosuric Effect Alprazolam has a weak uricosuric effect. Although other medications with weak uricosuric effect have been reported to cause acute renal failure, there have been no reported instances of acute renal failure attributable to therapy with Alprazolam. Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness It is recommended that the dosage be limited to the smallest effective dose to preclude the development of ataxia or oversedation which may be a particular problem in elderly or debilitated patients. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.) The usual precautions in treating patients with impaired renal, hepatic or pulmonary function should be observed. There have been rare reports of death in patients with severe pulmonary disease shortly after the initiation of treatment with Alprazolam. A decreased systemic alprazolam elimination rate (eg, increased plasma half-life) has been observed in both alcoholic liver disease patients and obese patients receiving Alprazolam (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

-

INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS

Information for Patients

For All Users Of Alprazolam:

To assure safe and effective use of benzodiazepines, all patients prescribed alprazolam should be provided with the following guidance. In addition, panic disorder patients, for whom doses greater than 4 mg/day are typically prescribed, should be advised about the risks associated with the use of higher doses.

-

Inform your physician about any alcohol consumption and medicine you are taking now, including medication you may buy without a prescription. Alcohol should generally not be used during treatment with benzodiazepines.

-

Not recommended for use in pregnancy. Therefore, inform your physician if you are pregnant, if you are planning to have a child, or if you become pregnant while you are taking this medication.

-

Inform your physician if you are nursing.

-

Until you experience how this medication affects you, do not drive a car or operate potentially dangerous machinery, etc.

-

Do not increase the dose even if you think the medication “does not work anymore” without consulting your physician. Benzodiazepines, even when used as recommended, may produce emotional and/or physical dependence.

-

Do not stop taking this medication abruptly or decrease the dose without consulting your physician, since withdrawal symptoms can occur.

Additional Advice For Panic Disorder Patients:

The use of alprazolam at doses greater than 4 mg/day, often necessary to treat panic disorder, is accompanied by risks that you need to carefully consider. When used at doses greater than 4 mg/day, which may or may not be required for your treatment, alprazolam has the potential to cause severe emotional and physical dependence in some patients and these patients may find it exceedingly difficult to terminate treatment. In two controlled trials of six to eight weeks duration where the ability of patients to discontinue medication was measured, 7 to 29% of patients treated with alprazolam did not completely taper off therapy. In a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients, the patients treated with doses of alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day had more difficulty tapering to zero dose than patients treated with less than 4 mg/day. In all cases, it is important that your physician help you discontinue this medication in a careful and safe manner to avoid overly extended use of alprazolam.

In addition, the extended use at doses greater than 4 mg/day appears to increase the incidence and severity of withdrawal reactions when alprazolam is discontinued. These are generally minor but seizure can occur, especially if you reduce the dose too rapidly or discontinue the medication abruptly. Seizure can be life-threatening.

-

- LABORATORY TESTS

-

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Drug Interactions

The benzodiazepines, including alprazolam, produce additive CNS depressant effects when coadministered with other psychotropic medications, anticonvulsants, antihistaminics, ethanol and other drugs which themselves produce CNS depression.

The steady state plasma concentrations of imipramine and desipramine have been reported to be increased an average of 31% and 20%, respectively, by the concomitant administration of alprazolam in doses up to 4 mg/day. The clinical significance of these changes is unknown.

Drugs That Inhibit Alprazolam Metabolism Via Cytochrome P450 3A:

The initial step in alprazolam metabolism is hydroxylation catalyzed by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP 3A). Drugs which inhibit this metabolic pathway may have a profound effect on the clearance of alprazolam (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS for additional drugs of this type.

Drugs Demonstrated To Be CYP 3A Inhibitors Of Possible Clinical Significance On The Basis Of Clinical Studies Involving Alprazolam (Caution Is Recommended During Coadministration With Alprazolam:

Fluoxetine--Coadministration of fluoxetine with alprazolam increased the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam by 46%, decreased clearance by 21%, increased half-life by 17%, and decreased measured psychomotor performance.

Propoxyphene--Coadministration of propoxyphene decreased the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam by 6%, decreased clearance by 38%; and increased half-life by 58%.

Oral contraceptives--Coadministration of oral contraceptives increased the maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam by 18%, decreased clearance by 22%, and increased half-life by 29%.

Drugs And Other Substances Demonstrated To Be CYP 3A Inhibitors On The Basis Of Clinical Studies Involving Benzodiazepines Metabolized Similarly To Alprazolam Or On The Basis Of In Vitro Studies With Alprazolam Or Other Benzodiazepines (Caution Is Recommended During Coadministration With Alprazolam):

Available data from clinical studies of benzodiazepines other than alprazolam suggest a possible drug interaction with alprazolam for the following: diltiazem, isoniazid, macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin and clarithromycin, and grapefruit juice. Data from in vitro studies of alprazolam suggest a possible drug interaction with alprazolam for the following: sertraline and paroxetine. Data from in vitro studies of benzodiazepines other than alprazolam suggest a possible drug interaction for the following: ergotamine, cyclosporine, amiodarone, nicardipine, and nifedipine. Caution is recommended during the coadministration of any of these with alprazolam (see WARNINGS).

- DRUG & OR LABORATORY TEST INTERACTIONS

-

CARCINOGENESIS & MUTAGENESIS & IMPAIRMENT OF FERTILITY

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

No evidence of carcinogenic potential was observed during 2-year bioassay studies of alprazolam in rats at doses up to 30 mg/kg/day (150 times the maximum recommended daily human dose of 10 mg/day) and in mice at doses up to 10 mg/kg/day (50 times the maximum recommended daily human dose).

Alprazolam was not mutagenic in the rat micronucleus test at doses up to 100 mg/kg, which is 500 times the maximum recommended daily human dose of 10 mg/day. Alprazolam also was not mutagenic in vitro in the DNA Damage/Alkaline Elution Assay or the Ames Assay.

Alprazolam produced no impairment of fertility in rats at doses up to 5 mg/kg/day, which is 25 times the maximum recommended daily human dose of 10 mg/day.

-

PREGNANCY

PregnancyTeratogenic Effects

Pregnancy category D: (see WARNINGS section)

Nonteratogenic EffectsIt should be considered that the child born of a mother who is receiving benzodiazepines may be at some risk for withdrawal symptoms from the drug during the postnatal period. Also, neonatal flaccidity and respiratory problems have been reported in children born of mothers who have been receiving benzodiazepines.

- LABOR & DELIVERY

-

NURSING MOTHERS

Nursing Mothers

Benzodiazepines are known to be excreted in human milk. It should be assumed that alprazolam is as well. Chronic administration of diazepam to nursing mothers has been reported to cause their infants to become lethargic and to lose weight. As a general rule, nursing should not be undertaken by mothers who must use alprazolam.

- PEDIATRIC USE

-

GERIATRIC USE

Geriatric Use

The elderly may be more sensitive to the effects of benzodiazepines. They exhibit higher plasma alprazolam concentrations due to reduced clearance of the drug as compared with a younger population receiving the same doses. The smallest effective dose of alprazolam should be used in the elderly to preclude the development of ataxia and oversedation (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Side effects to alprazolam, if they occur, are generally observed at the beginning of therapy and usually disappear upon continued medication. In the usual patient, the most frequent side effects are likely to be an extension of the pharmacological activity of alprazolam, eg, drowsiness or light-headedness.

The data cited in the two tables below are estimates of untoward clinical event incidence among patients who participated under the following clinical conditions: relatively short duration (ie, four weeks) placebo-controlled clinical studies with dosages up to 4 mg/day of alprazolam (for the management of anxiety disorders or for the short-term relief of the symptoms of anxiety) and short-term (up to ten weeks) placebo-controlled clinical studies with dosages up to 10 mg/day of alprazolam in patients with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

These data cannot be used to predict precisely the incidence of untoward events in the course of usual medical practice where patient characteristics, and other factors often differ from those in clinical trials. These figures cannot be compared with those obtained from other clinical studies involving related drug products and placebo as each group of drug trials are conducted under a different set of conditions.

Comparison of the cited figures, however, can provide the prescriber with some basis for estimating the relative contributions of drug and non-drug factors to the untoward event incidence in the population studied. Even this use must be approached cautiously, as a drug may relieve a symptom in one patient but induce it in others.

(For example, an anxiolytic drug may relieve dry mouth [a symptom of anxiety] in some subjects but induce it [an untoward event] in others.)

Additionally, for anxiety disorders the cited figures can provide the prescriber with an indication as to the frequency with which physician intervention (eg, increased surveillance, decreased dosage or discontinuation of drug therapy) may be necessary because of the untoward clinical event.

ANXIETY DISORDERS Treatment-Emergent Symptom Incidence† Incidence of Intervention

Because of Symptom*None reported †Events reported by 1% or more of alprazolam patients are included Alprazolam Placebo Alprazolam Number of Patients 565 505 565 % of Patients Reporting: CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM Drowsiness 41.0 21.6 15.1 Light-headedness 20.8 19.3 1.2 Depression 13.9 18.1 2.4 Headache 12.9 19.6 1.1 Confusion 9.9 10.0 0.9 Insomnia 8.9 18.4 1.3 Nervousness 4.1 10.3 1.1 Syncope 3.1 4.0 * Dizziness 1.8 0.8 2.5 Akathisia 1.6 1.2 * Tiredness/Sleepiness * * 1.8 GASTROINTESTINAL Dry Mouth 14.7 13.3 0.7 Constipation 10.4 11.4 0.9 Diarrhea 10.1 10.3 1.2 Nausea/Vomiting 9.6 12.8 1.7 Increased Salivation 4.2 2.4 * CARDIOVASCULAR Tachycardia/Palpitations 7.7 15.6 0.4 Hypotension 4.7 2.2 * SENSORY Blurred Vision 6.2 6.2 0.4 MUSCULOSKELETAL Rigidity 4.2 5.3 * Tremor 4.0 8.8 0.4 CUTANEOUS Dermatitis/Allergy 3.8 3.1 0.6 OTHER Nasal Congestion 7.3 9.3 * Weight Gain 2.7 2.7 * Weight Loss 2.3 3.0 * In addition to the relatively common (ie, greater than 1%) untoward events enumerated in the table above, the following adverse events have been reported in association with the use of benzodiazepines: dystonia, irritability, concentration difficulties, anorexia, transient amnesia or memory impairment, loss of coordination, fatigue, seizures, sedation, slurred speech, jaundice, musculoskeletal weakness, pruritus, diplopia, dysarthria, changes in libido, menstrual irregularities, incontinence and urinary retention.

PANIC DISORDER Treatment-Emergent

Symptom Incidence**Events reported by 1% or more of alprazolam patients are included. Alprazolam Placebo Number of Patients 1388 1231 % of Patients Reporting: Central Nervous System Drowsiness 76.8 42.7 Fatigue and Tiredness 48.6 42.3 Impaired Coordination 40.1 17.9 Irritability 33.1 30.1 Memory Impairment 33.1 22.1 Light-headedness/Dizziness 29.8 36.9 Insomnia 29.4 41.8 Headache 29.2 35.6 Cognitive Disorder 28.8 20.5 Dysarthria 23.3 6.3 Anxiety 16.6 24.9 Abnormal Involuntary Movement

14.8

21.0Decreased Libido 14.4 8.0 Depression 13.8 14.0 Confusional State 10.4 8.2 Muscular Twitching 7.9 11.8 Increased Libido 7.7 4.1 Change in Libido

(Not Specified)

7.1

5.6Weakness 7.1 8.4 Muscle Tone Disorders 6.3 7.5 Syncope 3.8 4.8 Akathisia 3.0 4.3 Agitation 2.9 2.6 Disinhibition 2.7 1.5 Paresthesia 2.4 3.2 Talkativeness 2.2 1.0 Vasomotor Disturbances 2.0 2.6 Derealization 1.9 1.2 Dream Abnormalities 1.8 1.5 Fear 1.4 1.0 Feeling Warm 1.3 0.5 Gastrointestinal Decreased Salivation 32.8 34.2 Constipation 26.2 15.4 Nausea/Vomiting 22.0 31.8 Diarrhea 20.6 22.8 Abdominal Distress 18.3 21.5 Increased Salivation 5.6 4.4 Cardio-Respiratory Nasal Congestion 17.4 16.5 Tachycardia 15.4 26.8 Chest Pain 10.6 18.1 Hyperventilation 9.7 14.5 Upper Respiratory Infection 4.3 3.7 Sensory Blurred Vision 21.0 21.4 Tinnitus 6.6 10.4 Musculoskeletal Muscular Cramps 2.4 2.4 Muscle Stiffness 2.2 3.3 Cutaneous Sweating 15.1 23.5 Rash 10.8 8.1 Other Increased 32.7 22.8 Decreased Appetite 27.8 24.1 Weight Gain 27.2 17.9 Weight Loss 22.6 16.5 Micturition Difficulties 12.2 8.6 Menstrual Disorders 10.4 8.7 Sexual Dysfunction 7.4 3.7 Edema 4.9 5.6 Incontinence 1.5 0.6 Infection 1.3 1.7 In addition to the relatively common (ie, greater than 1%) untoward events enumerated in the table above, the following adverse events have been reported in association with the use of alprazolam: seizures, hallucinations, depersonalization, taste alterations, diplopia, elevated bilirubin, elevated hepatic enzymes, and jaundice.

There have also been reports of withdrawal seizures upon rapid decrease or abrupt discontinuation of alprazolam (see WARNINGS).

To discontinue treatment in patients taking alprazolam, the dosage should be reduced slowly in keeping with good medical practice. It is suggested that the daily dosage of alprazolam be decreased by no more than 0.5 mg every three days (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Some patients may benefit from an even slower dosage reduction. In a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients which compared this recommended taper schedule with a slower taper schedule, no difference was observed between the groups in the proportion of patients who tapered to zero dose; however, the slower schedule was associated with a reduction in symptoms associated with a withdrawal syndrome.

Panic disorder has been associated with primary and secondary major depressive disorders and increased reports of suicide among untreated patients. Therefore, the same precaution must be exercised when using doses of alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day in treating patients with panic disorders as is exercised with the use of any psychotropic drug in treating depressed patients or those in whom there is reason to expect concealed suicidal ideation or plans.

As with all benzodiazepines, paradoxical reactions such as stimulation, increased muscle spasticity, sleep disturbances, hallucinations and other adverse behavioral effects such as agitation, rage, irritability, and aggressive or hostile behavior have been reported rarely. In many of the spontaneous case reports of adverse behavioral effects, patients were receiving other CNS drugs concomitantly and/or were described as having underlying psychiatric conditions. Should any of the above events occur, alprazolam should be discontinued. Isolated published reports involving small numbers of patients have suggested that patients who have borderline personality disorder, a prior history of violent or aggressive behavior, or alcohol or substance abuse may be at risk for such events. Instances of irritability, hostility, and intrusive thoughts have been reported during discontinuation of alprazolam in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder.

Laboratory analyses were performed on all patients participating in the clinical program for alprazolam. The following incidences of abnormalities shown below were observed in patients receiving alprazolam and in patients in the corresponding placebo group. Few of these abnormalities were considered to be of physiological significance.

Placebo LOW HIGH LOW HIGH *Less Than 1% HEMATOLOGY Hematocrit * * * * Hemoglobin * * * * Total WBC Count 1.4 2.3 1.0 2.0 Neutrophil Count 2.3 3.0 4.2 1.7 Lymphocyte Count 5.5 7.4 5.4 9.5 Monocyte Count 5.3 2.8 6.4 * Eosinophil Count 3.2 9.5 3.3 7.2 Basophil Count * * * * URINALYSIS Albumin -- * -- * Sugar -- * -- * RBC/HPF -- 3.4 -- 5.0 WBC/HPF -- 25.7 -- 25.9 BLOOD CHEMISTRY Creatinine 2.2 1.9 3.5 1.0 Bilirubin * 1.6 * * SGOT * 3.2 1.0 1.8 Alkaline Phosphatase * 1.7 * 1.8 When treatment with alprazolam is protracted, periodic blood counts, urinalysis and blood chemistry analyses are advisable.

Minor changes in EEG patterns, usually low-voltage fast activity have been observed in patients during therapy with alprazolam and are of no known significance.

Post Introduction Reports: Various adverse drug reactions have been reported in association with the use of alprazolam since market introduction. The majority of these reactions were reported through the medical event voluntary reporting system. Because of the spontaneous nature of the reporting of medical events and the lack of controls, a causal relationship to the use of alprazolam cannot be readily determined. Reported events include: liver enzyme elevations, hepatitis, hepatic failure, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, gynecomastia and galactorrhea.

-

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

Physical And Psychological Dependence: Withdrawal symptoms similar in character to those noted with sedative/hypnotics and alcohol have occurred following abrupt discontinuance of benzodiazepines, including alprazolam. The symptoms can range from mild dysphoria and insomnia to a major syndrome that may include abdominal and muscle cramps, vomiting, sweating, tremors and convulsions. Distinguishing between withdrawal emergent signs and symptoms and the recurrence of illness is often difficult in patients undergoing dose reduction. The long term strategy for treatment of these phenomena will vary with their cause and the therapeutic goal. When necessary, immediate management of withdrawal symptoms requires re-institution of treatment at doses of alprazolam sufficient to suppress symptoms. There have been reports of failure of other benzodiazepines to fully suppress these withdrawal symptoms. These failures have been attributed to incomplete cross-tolerance but may also reflect the use of an inadequate dosing regimen of the substituted benzodiazepine or the effects of concomitant medications.

While it is difficult to distinguish withdrawal and recurrence for certain patients, the time course and the nature of the symptoms may be helpful. A withdrawal syndrome typically includes the occurrence of new symptoms, tends to appear toward the end of taper or shortly after discontinuation, and will decrease with time. In recurring panic disorder, symptoms similar to those observed before treatment may recur either early or late, and they will persist.

While the severity and incidence of withdrawal phenomena appear to be related to dose and duration of treatment, withdrawal symptoms, including seizures, have been reported after only brief therapy with alprazolam at doses within the recommended range for the treatment of anxiety (eg, 0.75 to 4 mg/day). Signs and symptoms of withdrawal are often more prominent after rapid decrease of dosage or abrupt discontinuance. The risk of withdrawal seizures may be increased at doses above 4 mg/day (see WARNINGS).

Patients, especially individuals with a history of seizures or epilepsy, should not be abruptly discontinued from any CNS depressant agent, including alprazolam. It is recommended that all patients on alprazolam who require a dosage reduction be gradually tapered under close supervision (see WARNINGS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Psychological dependence is a risk with all benzodiazepines, including alprazolam. The risk of psychological dependence may also be increased at doses greater than 4 mg/day and with longer term use, and this risk is further increased in patients with a history of alcohol or drug abuse. Some patients have experienced considerable difficulty in tapering and discontinuing from alprazolam, especially those receiving higher doses for extended periods. Addiction-prone individuals should be under careful surveillance when receiving alprazolam. As with all anxiolytics, repeat prescriptions should be limited to those who are under medical supervision.

- CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE

-

OVERDOSAGE

OVERDOSAGE

Manifestations of alprazolam overdosage include somnolence, confusion, impaired coordination, diminished reflexes and coma. Death has been reported in association with overdoses of alprazolam by itself, as it has with other benzodiazepines. In addition, fatalities have been reported in patients who have overdosed with a combination of a single benzodiazepine, including alprazolam, and alcohol; alcohol levels seen in some of these patients have been lower than those usually associated with alcohol-induced fatality.

The acute oral LD50 in rats is 331 to 2171 mg/kg. Other experiments in animals have indicated that cardiopulmonary collapse can occur following massive intravenous doses of alprazolam (over 195 mg/kg; 975 times the maximum recommended daily human dose of 10 mg/day). Animals could be resuscitated with positive mechanical ventilation and the intravenous infusion of norepinephrine bitartrate.

Animal experiments have suggested that forced diuresis or hemodialysis are probably of little value in treating overdosage.

General Treatment Of Overdose: Overdosage reports with alprazolam tablets are limited. As in all cases of drug overdosage, respiration, pulse rate, and blood pressure should be monitored. General supportive measures should be employed, along with immediate gastric lavage. Intravenous fluids should be administered and an adequate airway maintained. If hypotension occurs, it may be combated by the use of vasopressors. Dialysis is of limited value. As with the management of intentional overdosing with any drug, it should be borne in mind that multiple agents may have been ingested.

Flumazenil, a specific benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, is indicated for the complete or partial reversal of the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and may be used in situations when an overdose with a benzodiazepine is known or suspected. Prior to the administration of flumazenil, necessary measures should be instituted to secure airway, ventilation, and intravenous access. Flumazenil is intended as an adjunct to, not as a substitute for, proper management of benzodiazepine overdose. Patients treated with flumazenil should be monitored for re-sedation, respiratory depression, and other residual benzodiazepine effects for an appropriate period after treatment. The prescriber should be aware of a risk of seizure in association with flumazenil treatment, particularly in long-term benzodiazepine users and in cyclic antidepressant overdose. The complete flumazenil package insert including CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS, and PRECAUTIONS should be consulted prior to use.

-

DOSAGE & ADMINISTRATION

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Dosage should be individualized for maximum beneficial effect. While the usual daily dosages given below will meet the needs of most patients, there will be some who require doses greater than 4 mg/day. In such cases, dosage should be increased cautiously to avoid adverse effects.

Anxiety Disorders And Transient Symptoms Of Anxiety:Treatment for patients with anxiety should be initiated with a dose of 0.25 to 0.5 mg given three times daily. The dose may be increased to achieve a maximum therapeutic effect, at intervals of 3 to 4 days, to a maximum daily dose of 4 mg, given in divided doses. The lowest possible effective dose should be employed and the need for continued treatment reassessed frequently. The risk of dependence may increase with dose and duration of treatment.

In elderly patients, in patients with advanced liver disease or in patients with debilitating disease, the usual starting dose is 0.25 mg, given two or three times daily. This may be gradually increased if needed and tolerated. The elderly may be especially sensitive to the effects of benzodiazepines.

If side effects occur at the recommended starting dose, the dose may be lowered.

In all patients, dosage should be reduced gradually when discontinuing therapy or when decreasing the daily dosage. Although there are no systematically collected data to support a specific discontinuation schedule, it is suggested that the daily dosage be decreased by no more than 0.5 mg every three days. Some patients may require an even slower dosage reduction.

Panic Disorder:The successful treatment of many panic disorder patients has required the use of alprazolam at doses greater than 4 mg daily. In controlled trials conducted to establish the efficacy of alprazolam in panic disorder, doses in the range of 1 to 10 mg daily were used. The mean dosage employed was approximately 5 to 6 mg daily. Among the approximately 1700 patients participating in the panic disorder development program, about 300 received alprazolam in dosages of greater than 7 mg/day, including approximately 100 patients who received maximum dosages of greater than 9 mg/day. Occasional patients required as much as 10 mg a day to achieve a successful response.

Generally, therapy should be initiated at a low dose to minimize the risk of adverse responses in patients especially sensitive to the drug. Thereafter, the dose can be increased at intervals equal to at least 5 times the elimination half-life (about 11 hours in young patients, about 16 hours in elderly patients). Longer titration intervals should probably be used because the maximum therapeutic response may not occur until after the plasma levels achieve steady state. Dose should be advanced until an acceptable therapeutic response (ie, a substantial reduction in or total elimination of panic attacks) is achieved, intolerance occurs, or the maximum recommended dose is attained. For patients receiving doses greater than 4 mg/day, periodic reassessment and consideration of dosage reduction is advised. In a controlled postmarketing dose-response study, patients treated with doses of alprazolam greater than 4 mg/day for three months were able to taper to 50% of their total maintenance dose without apparent loss of clinical benefit.

Because of the danger of withdrawal, abrupt discontinuation of treatment should be avoided. (See WARNINGS, PRECAUTIONS, DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

The following regimen is one that follows the principles outlined above:

Treatment may be initiated with a dose of 0.5 mg three times daily. Depending on the response, the dose may be increased at intervals of 3 to 4 days in increments of no more than 1 mg per day. Slower titration to the dose levels greater than 4 mg/day may be advisable to allow full expression of the pharmacodynamic effect of alprazolam. To lessen the possibility of interdose symptoms, the times of administration should be distributed as evenly as possible throughout the waking hours, that is, on a three or four times per day schedule.

The necessary duration of treatment for panic disorder patients responding to alprazolam is unknown. After a period of extended freedom from attacks, a carefully supervised tapered discontinuation may be attempted, but there is evidence that this may often be difficult to accomplish without recurrence of symptoms and/or the manifestation of withdrawal phenomena.

In any case, reduction of dose must be undertaken under close supervision and must be gradual. If significant withdrawal symptoms develop, the previous dosing schedule should be reinstituted and, only after stabilization, should a less rapid schedule of discontinuation be attempted. In a controlled postmarketing discontinuation study of panic disorder patients which compared this recommended taper schedule with a slower taper schedule, no difference was observed between the groups in the proportion of patients who tapered to zero dose; however, the slower schedule was associated with a reduction in symptoms associated with a withdrawal syndrome. It is suggested that the dose be reduced by no more than 0.5 mg every three days, with the understanding that some patients may benefit from an even more gradual discontinuation. Some patients may prove resistant to all discontinuation regimens.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

HOW SUPPLIED

Alprazolam Tablets, USP are supplied as follows:

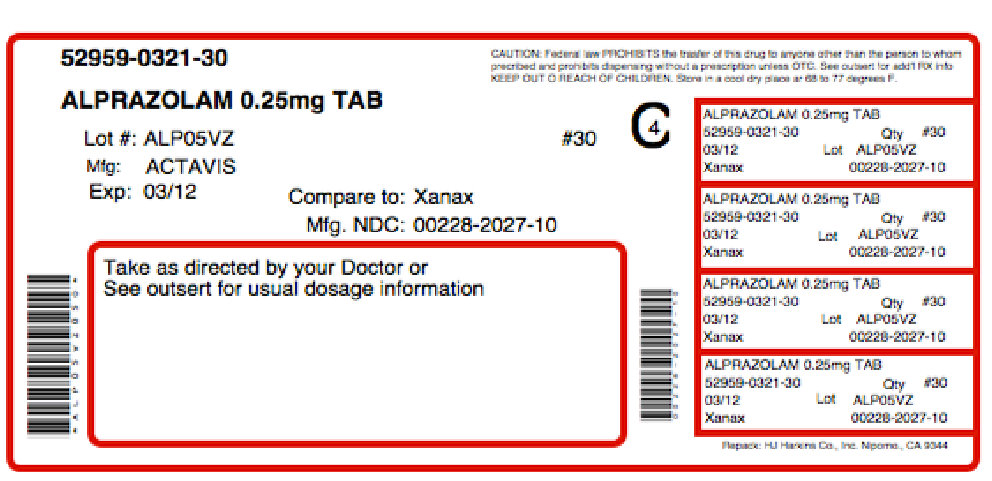

0.25 mg — Each white, round tablet imprinted with on one side and 027 and bisect on the other contains 0.25 mg of Alprazolam, USP. Tablets are supplied in bottles of 100 (NDC: 0228-2027-10), 500 (NDC: 0228-2027-50), and 1000 (NDC: 0228-2027-96).

0.5 mg — Each peach, round tablet imprinted with on one side and 029 and bisect on the other contains 0.5 mg of Alprazolam, USP. Tablets are supplied in bottles of 100 (NDC: 0228-2029-10), 500 (NDC: 0228-2029-50), and 1000 (NDC: 0228-2029-96).

1 mg — Each blue, round tablet imprinted with on one side and 031 and bisect on the other contains 1 mg of Alprazolam, USP. Tablets are supplied in bottles of 100 (NDC: 0228-2031-10), 500 (NDC: 0228-2031-50), and 1000 (NDC: 0228-2031-96).

2 mg — Each yellow, rectangle shaped, flat faced, beveled edge tablet imprinted with and 039 on one side and multiscored on both sides contains 2 mg of Alprazolam, USP. Tablets are supplied in bottles of 100 (NDC: 0228-2039-10), and 500 (NDC: 0228-2039-50).

Dispense in tight, light-resistant containers as defined in the USP.

Keep container tightly closed.

Store at controlled room temperature 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F) [see USP].

- STORAGE AND HANDLING

-

ANIMAL PHARMACOLOGY & OR TOXICOLOGY

ANIMAL PHARMACOLOGYAnimal Studies

When rats were treated with alprazolam at 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg/day (15 to 150 times the maximum recommended human dose) orally for 2 years, a tendency for a dose related increase in the number of cataracts was observed in females and a tendency for a dose related increase in corneal vascularization was observed in males. These lesions did not appear until after 11 months of treatment.

CLINICAL STUDIESAnxiety Disorders: Alprazolam tablets were compared to placebo in double blind clinical studies (doses up to 4 mg/day) in patients with a diagnosis of anxiety or anxiety with associated depressive symptomatology. Alprazolam was significantly better than placebo at each of the evaluation periods of these four week studies as judged by the following psychometric instruments: Physician’s Global Impressions, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Target Symptoms, Patient’s Global Impressions and Self-Rating Symptom Scale.

Panic Disorder: Support for the effectiveness of alprazolam in the treatment of panic disorder came from three short-term, placebo-controlled studies (up to 10 weeks) in patients with diagnoses closely corresponding to DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder.

The average dose of alprazolam was 5-6 mg/day in two of the studies, and the doses of alprazolam were fixed at 2 and 6 mg/day in the third study. In all three studies, alprazolam was superior to placebo on a variable defined as "the number of patients with zero panic attacks" (range, 37-83% met this criterion), as well as on a global improvement score. In two of the three studies, alprazolam was superior to placebo on a variable defined as "change from baseline on the number of panic attacks per week" (range, 3.3-5.2), and also on a phobia rating scale. A subgroup of patients who were improved on alprazolam during short-term treatment in one of these trials was continued on an open basis up to eight months, without apparent loss of benefit.

Manufactured by:

Actavis Elizabeth LLC

200 Elmora Avenue

Elizabeth, NJ 07207 USA

40-8786

Revised — January 2006

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

GABAdone (US patent pending) capsules by oral administration. A specially formulated Medical Food product, consisting of a proprietary blend of amino acids and polyphenol ingredients in specific proportions, for the dietary management of the metabolic processes of sleep disorders (SD).

Must be administered under physician supervision.

Medical Foods

Medical Food products are often used in hospitals (e.g., for burn victims or kidney dialysis patients) and outside of a hospital setting under a physician’s care for the dietary management of diseases in patients with particular medical or metabolic needs due to their disease or condition. Congress defined "Medical Food" in the Orphan Drug Act and Amendments of 1988 as "a system which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally [or orally] under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation." Medical Foods are complex formulated products, requiring sophisticated and exacting technology. GABAdone has been developed, manufactured, and labeled in accordance with both the statutory and the FDA regulatory definition of a Medical Food. GABAdone must be used while the patient is under the ongoing care of a physician.

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

SLEEP DISORDERS (SD)

SD as a Metabolic Deficiency Disease

A critical component of the definition of a Medical Food is the requirement for a distinctive nutritional deficiency. FDA scientists have proposed a physiologic definition of a distinctive nutritional deficiency as follows: “the dietary management of patients with specific diseases requires, in some instances, the ability to meet nutritional requirements that differ substantially from the needs of healthy persons. For example, in establishing the recommended dietary allowances for general, healthy population, the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine National Academy of Sciences, recognized that different or distinctive physiologic requirements may exist for certain persons with "special nutritional needs arising from metabolic disorders, chronic diseases, injuries, premature birth, other medical conditions and drug therapies. Thus, the distinctive nutritional needs associated with a disease reflect the total amount needed by a healthy person to support life or maintain homeostasis, adjusted for the distinctive changes in the nutritional needs of the patient as a result of the effects of the disease process on absorption, metabolism, and excretion.” It was also proposed that in patients with certain disease states who respond to nutritional therapies, a physiologic deficiency of the nutrient is assumed to exist. For example, if a patient with sleep disorders responds to a tryptophan formulation by improving the duration and quality of sleep, a deficiency of tryptophan is assumed to exist.

Patients with sleep disorders are known to have nutritional deficiencies of tryptophan, choline, flavonoids, and certain antioxidants. Patients with sleep disorders frequently exhibit reduced plasma levels of tryptophan and have been shown to respond to oral administration of tryptophan or a 5-hydoxytryptophan formulation. Research has shown that tryptophan reduced diets result in a fall in circulating tryptophan. Patients with sleep disorders frequently experience activation of the tryptophan degradation pathway that increases the turnover of tryptophan leading to a reduced level of production of serotonin for a given tryptophan blood level. Research has also shown that a genetic predisposition to accelerated tryptophan degradation can lead to increased tryptophan requirements in certain patients with sleep disorders.

Choline is required to fully potentiate acetylcholine synthesis by brain neurons. A deficiency of choline leads to reduced acetylcholine production by the neurons. Low fat diets, frequently used by patients with sleep disorders, are usually choline deficient. Flavonoids potentiate the production of acetylcholine by the neurons thereby inducing REM sleep. Low fat diets and diets deficient in flavonoid rich foods result in inadequate flavonoid concentrations, impeding acetylcholine production in certain patients with sleep disorders. Provision of tryptophan, choline, and flavonoids with antioxidants, in specific proportions can restore the production of beneficial serotonin and acetylcholine, thereby improving sleep quality.

-

DESCRIPTION

PRODUCT DESCRIPTION

Primary Ingredients

GABAdone consists of a proprietary blend of amino acids, cocoa, ginkgo biloba and flavonoids in specific proportions. These ingredients fall into the category of “Generally Regarded as Safe” (GRAS) as defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Sections 201(s) and 409 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act). A GRAS substance is distinguished from a food additive on the basis of the common knowledge about the safety of the substance for its intended use. The standard for an ingredient to achieve GRAS status requires not only technical demonstration of non-toxicity and safety, but also general recognition of safety through widespread usage and agreement of that safety by experts in the field. Many ingredients have been determined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be GRAS, and are listed as such by regulation, in Volume 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Sections 182, 184, and 186.

Amino Acids

Amino Acids are the building blocks of protein. All amino acids are GRAS listed as they have been ingested by humans for thousands of years. The doses of the amino acids in GABAdone are equivalent to those found in the usual human diet; however the formulation uses specific ratios of the key ingredients to elicit a therapeutic response. Tryptophan, for example, is an obligatory amino acid. The body cannot make tryptophan and must obtain tryptophan from the diet. Tryptophan is needed to produce serotonin. Serotonin is required to induce sleep. Patients with sleep disorders have altered serotonin metabolism. Some patients with sleep disorders have a resistance to the use of tryptophan that is similar to the mechanism found in insulin resistance. Patients with sleep disorders cannot acquire sufficient tryptophan from the diet to establish normal sleep architecture without ingesting a prohibitively large amount of calories, particularly calories from protein.

Flavonoids

Flavonoids are a group of phytochemical compounds found in all vascular plants including fruits and vegetables. They are a part of a larger class of compounds known as polyphenols. Many of the therapeutic or health benefits of colored fruits and vegetables, cocoa, red wine, and green tea are directly related to their flavonoid content. The amounts of specially formulated flavonoids found in GABAdone cannot be obtained from conventional foods in the necessary proportions to elicit a therapeutic response.

Physical Description

GABAdone is a yellow to light brown powder. GABAdone contains L-Glutamic Acid, 5-Hydroxytryptophan as Griffonia Seed Extract, Acetyl L-Carnitine HCL, Gamma Amino Butyric Acid, Choline Bitartrate, Hydrolyzed Whey Protein, Cocoa, Ginkgo Biloba, Valerian Root, and Grape Seed Extract.

Other Ingredients

GABAdone contains the following inactive or other ingredients, as fillers, excipients, and colorings: magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, Maltodextrin NF, gelatin (as the capsule material). -

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

GABAdone acts by restoring and maintaining the balance of the neurotransmitters, serotonin, and acetylcholine that are required for maintaining normal sleep architecture. A deficiency of these neurotransmitters is associated with sleep disorders.

Metabolism

The amino acids in GABAdone are primarily absorbed by the stomach and small intestines. All cells metabolize the amino acids in GABAdone. Circulating tryptophan and choline blood levels determine the production of serotonin and acetylcholine.

Excretion

GABAdone is not an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, or 3A4. These isoenzymes are principally responsible for 95% of all detoxification of drugs, with CYP3A4 being responsible for detoxification of roughly 50% of drugs. Amino acids do not appear to have an effect on drug metabolizing enzymes. -

INDICATIONS & USAGE

INDICATIONS FOR USE

GABAdone is intended for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes in patients with sleep disorders and sleep disorders associated with anxiety.

- Insomnia

- Sleep maintenance insomnia

- Sleep disorders of circadian origin

- Sleep disorders associated with anxiety

- Snoring -

CLINICAL STUDIES

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Patients taking GABAdone have demonstrated significant functional improvements when this therapeutic agent is used for the dietary management of the metabolic processes associated with sleep disorders. The administration of GABAdone results in the induction and maintenance of sleep in patients with sleep disorders. GABAdone has no effect on normal blood pressure. - PRECAUTIONS

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Oral supplementation with L-tryptophan or choline at high doses up to 15 grams daily is generally well tolerated. The most common adverse reactions of higher doses — from 15 to 30 grams daily — are nausea, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Some patients may experience these symptoms at lower doses. The total combined amount of amino acids in each GABAdone capsule does not exceed 400 mg. - DRUG INTERACTIONS

-

OVERDOSAGE

OVERDOSE

There is a negligible risk of overdose with GABAdone as the total dosage of amino acids in a one month supply (60 capsules) is less than 25 grams. Overdose symptoms may include diarrhea, weakness, and nausea.

POST-MARKETING SURVEILLANCE

Post-marketing surveillance has shown no serious adverse reactions. Reported cases of mild rash and itching may have been associated with allergies to GABAdone flavonoid ingredients, including cinnamon, cocoa, and chocolate. The reactions were transient in nature and subsided within 24 hours. -

DOSAGE & ADMINISTRATION

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Recommended Administration

For the dietary management of the metabolic processes in patients with sleep disorders. Take (2) capsules daily at bedtime. An additional dose of one or two capsules may be taken after awakenings during the night. As with most amino acid formulations GABAdone should be taken without food to increase the absorption of key ingredients. -

HOW SUPPLIED

How Supplied

GABAdone is supplied in blue and white, size 0 capsules in bottles of 60 capsules.

Physician Supervision

GABAdone is a Medical Food product available by prescription only and must be used while the patient is under ongoing physician supervision.

U.S. patent pending.

Manufactured by Arizona Nutritional Supplements, Inc. Chandler AZ 85225

Distributed by Physician Therapeutics LLC, Los Angeles, CA 90077. www.ptlcentral.com

© Copyright 2003-2006, Physician Therapeutics LLC, all rights reserved

NDC # 68405-1004-02 - STORAGE AND HANDLING

-

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

Directions for use: Must be administered under physician supervision. For adults only. As a Medical Food, take one (1) or two (2) capsules daily at bedtime or as directed by physician. Fot the dietary management of sleep disorders. Contains no added sugar, starch, wheat, yeast, preservatives, artificial flavor. Storage: Keep tightly closed in a cool dry place 8-32 degree centigrade (45-90 degree F), relative humidity, below 50%. Warning: Keep this product out of the reach of children. NDC# 68405-1004-02 PHYSICIAN THERAPEUTICS GABADONE Medical Food Rx only 60 Capsules Ingredients: Each serving (per 2 capsules) contains: Proprietary Amino Acid Blend Choline Bitartrate, Gamma Amino Butyric Acid (GABA), Glutamic Acid (L-Glutamic Acid), Whey Protein Hydrolysate 80%, Griffonia Seed Extract (5-HTP), Cocoa Extract (fruit), Proprietary Herbal Blend Indian Valerian Extract 4:1 (root), Ginkgo Biloba (leaves), Acetyl L-Carnitine HCI, Grape Extract (95% Polyphenols) (seed) Other IngredientsL Gelatin, tricalcium phosphate, silicon dioxide, vegetable magnesium stearate, FDandC blue #1, titanium dioxide. Distributed exclusively by: Physicians Therapeutics LLC A Divisions of Targeted Medical Pharma, Inc. Los Angeles, CA 90077 www.ptlcentral.com Patent Pending 68405-1004-02

-

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

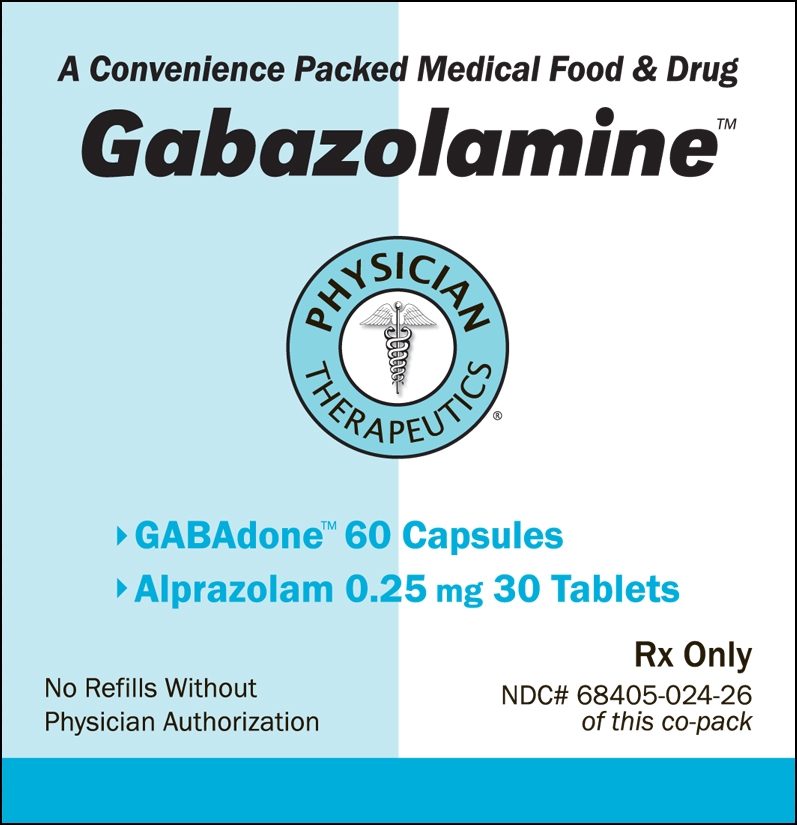

For the Dietary Management of Sleep Disorders. Two capsules at bedtime or as directed by physician. See product label and insert. GADAdone Medical Food A Convenience Packed Medical Food And Drug Gabazolamine PHYSICIAN THERAPEUTICS - GABAdone 60 Capsules - Alprazolam 0.25 mg 30 Tablets Rx Only No Refills Without NDC# 68405-8024-26 Physician Authorization of this co-pack FRONT VIEW

As prescribed by physician. See product label and product information insert. Alprazolam 0.25 mg Rx Drug 68405-8024-26 BACK VIEW Physician Therapeutics LLC Los Angeles, CA 90077 on November 21, 2006

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

GABAZOLAMINE

alprazolam, choline kitProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 68405-024 Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 68405-024-26 1 in 1 KIT Quantity of Parts Part # Package Quantity Total Product Quantity Part 1 1 BOTTLE 30 Part 2 1 BOTTLE 60 Part 1 of 2 ALPRAZOLAM

alprazolam tabletProduct Information Item Code (Source) NDC: 52959-321(NDC:0228-2027) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ALPRAZOLAM (UNII: YU55MQ3IZY) (ALPRAZOLAM - UNII:YU55MQ3IZY) ALPRAZOLAM 0.25 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) STARCH, CORN (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) DOCUSATE SODIUM (UNII: F05Q2T2JA0) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SODIUM BENZOATE (UNII: OJ245FE5EU) Product Characteristics Color white (WHITE) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code R027 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 52959-321-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA074342 07/07/2011 Part 2 of 2 GABADONE