FANAPT- iloperidone tablet

Fanapt by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Fanapt by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Avera McKennan Hospital. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use FANAPT safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for FANAPT.

FANAPT® (iloperidone) tablets

Initial U.S. Approval: 2009

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. FANAPT is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis. (5.1)

RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

Contraindications (4) 1/2016

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

FANAPT is an atypical antipsychotic agent indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults. (1) Efficacy was established in two short-term (4- and 6-week) placebo- and active-controlled studies of adult patients with schizophrenia. (14) In choosing among treatments, prescribers should consider the ability of FANAPT to prolong the QT interval and the use of other drugs first. Prescribers should also consider the need to titrate FANAPT slowly to avoid orthostatic hypotension, which may lead to delayed effectiveness compared to some other drugs that do not require similar titration.

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The recommended target dosage of FANAPT tablets is 12 to 24 mg/day administered twice daily. This target dosage range is achieved by daily dosage adjustments, alerting patients to symptoms of orthostatic hypotension, starting at a dose of 1 mg twice daily, then moving to 2 mg, 4 mg, 6 mg, 8 mg, 10 mg, and 12 mg twice daily on Days 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 respectively, to reach the 12 mg/day to 24 mg/day dose range. FANAPT can be administered without regard to meals. (2.1)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

1 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg, 6 mg, 8 mg, 10 mg and 12 mg tablets. (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis who are treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death and cerebrovascular-related adverse events, including stroke. (5.1)

- QT prolongation: Prolongs QT interval and may be associated with arrhythmia and sudden death-consider using other antipsychotics first. Avoid use of FANAPT in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong QTc; use caution and consider dose modification when prescribing FANAPT with other drugs that inhibit FANAPT metabolism. Monitor serum potassium and magnesium in patients at risk for electrolyte disturbances. (1, 5.2, 7.1, 7.3, 12.3)

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Manage with immediate discontinuation of drug and close monitoring. (5.3)

- Tardive dyskinesia: Discontinue if clinically appropriate. (5.4)

-

Metabolic Changes: Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and weight gain. (5.5)

- Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus: Monitor patients for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Monitor glucose regularly in patients at risk for diabetes. (5.5)

- Dyslipidemia: Undesirable alterations have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. (5.5)

- Weight Gain: Weight gain has been reported. Monitor weight. (5.5)

- Seizures: Use cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower seizure threshold. (5.6)

- Orthostatic hypotension: Dizziness, tachycardia, and syncope can occur with standing. (5.7)

- Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis have been reported with antipsychotics. Patients with a pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC) or a history of leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and should discontinue FANAPT at the first sign of a decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors. (5.8)

- Suicide: Close supervision of high risk patients. (5.12)

- Priapism: Cases have been reported in association with FANAPT treatment. (5.13)

- Potential for cognitive and motor impairment: Use caution when operating machinery. (5.14)

- See Full Prescribing Information for additional WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and 2-fold greater than placebo) were: dizziness, dry mouth, fatigue, nasal congestion, orthostatic hypotension, somnolence, tachycardia, and weight increased. (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. at 1-844-GO-VANDA (1-844-468-2632) or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

- Pregnancy: No human or animal data. Use only if clearly needed. (8.1)

- Nursing Mothers: Should not breastfeed. (8.3)

- Pediatric Use: Safety and effectiveness not established in children and adolescents. (8.4)

- Hepatic Impairment:. FANAPT is not recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment. (2.2, 8.7)

- The dose of FANAPT should be reduced in patients who are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. (2.2, 12.3)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION.

Revised: 3/2017

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Usual Dose

2.2 Dosage in Special Populations

2.3 Maintenance Treatment

2.4 Reinitiation of Treatment in Patients Previously Discontinued

2.5 Switching from Other Antipsychotics

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Risks in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

5.2 QT Prolongation

5.3 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

5.4 Tardive Dyskinesia

5.5 Metabolic Changes

5.6 Seizures

5.7 Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

5.8 Leukopenia, Neutropenia and Agranulocytosis

5.9 Hyperprolactinemia

5.10 Body Temperature Regulation

5.11 Dysphagia

5.12 Suicide

5.13 Priapism

5.14 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Studies Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Potential for Other Drugs to Affect FANAPT

7.2 Potential for FANAPT to Affect Other Drugs

7.3 Drugs that Prolong the QT Interval

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Labor and Delivery

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Renal Impairment

8.7 Hepatic Impairment

8.8 Smoking Status

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

10.2 Management of Overdose

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

17.1 QT Interval Prolongation

17.2 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

17.3 Metabolic Changes

17.4 Orthostatic Hypotension

17.5 Interference with Cognitive and Motor Performance

17.6 Pregnancy

17.7 Nursing

17.8 Concomitant Medication

17.9 Alcohol

17.10 Heat Exposure and Dehydration

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analysis of seventeen placebo-controlled trials (modal duration 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in the drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature.

Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. FANAPT is not approved for the treatment of patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

FANAPT® tablets are indicated for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. Efficacy was established in two short-term (4- and 6-week) placebo-and active-controlled studies of adult patients with schizophrenia [see Clinical Studies (14)].

When deciding among the alternative treatments available for this condition, the prescriber should consider the finding that FANAPTis associated with prolongation of the QTc interval [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. Prolongation of the QTc interval is associated in some other drugs with the ability to cause torsade de pointes-type arrhythmia, a potentially fatal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia which can result in sudden death. In many cases this would lead to the conclusion that other drugs should be tried first. Whether FANAPT will cause torsade de pointes or increase the rate of sudden death is not yet known.

Patients must be titrated to an effective dose of FANAPT.Thus, control of symptoms may be delayed during the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment compared to some other antipsychotic drugs that do not require a similar titration. Prescribers should be mindful of this delay when selecting an antipsychotic drug for the treatment of schizophrenia [see Dosage and Administration (2.1) and Clinical Studies (14)].

The effectiveness of FANAPT in long-term use, that is, for more than 6 weeks, has not been systematically evaluated in controlled trials. Therefore, the physician who elects to use FANAPT for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient [see Dosage and Administration (2.3)].

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Usual Dose

FANAPT must be titrated slowly from a low starting dose to avoid orthostatic hypotension due to its alpha-adrenergic blocking properties. The recommended starting dose for FANAPT tablets is 1 mg twice daily. Dose increases to reach the target range of 6-12 mg twice daily (12_24 mg/day) may be made with daily dosage adjustments not to exceed 2 mg twice daily (4 mg/day). The maximum recommended dose is 12 mg twice daily (24 mg/day). FANAPT doses above 24 mg/day have not been systematically evaluated in the clinical trials. Efficacy was demonstrated with FANAPT in a dose range of 6 to 12 mg twice daily. Prescribers should be mindful of the fact that patients need to be titrated to an effective dose of FANAPT. Thus, control of symptoms may be delayed during the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment compared to some other antipsychotic drugs that do not require similar titration. Prescribers should also be aware that some adverse effects associated with FANAPT use are dose related.

FANAPT can be administered without regard to meals.

2.2 Dosage in Special Populations

Dosage adjustments are not routinely indicated on the basis of age, gender, race, or renal impairment status [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6, 8.7)].

Dosage adjustment for patients taking FANAPT concomitantly with potential CYP2D6 inhibitors: FANAPT dose should be reduced by one-half when administered concomitantly with strong CYP2D6 inhibitors such as fluoxetine or paroxetine. When the CYP2D6 inhibitor is withdrawn from the combination therapy, FANAPT dose should then be increased to where it was before [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Dosage adjustment for patients taking FANAPT concomitantly with potential CYP3A4 inhibitors: FANAPT dose should be reduced by one-half when administered concomitantly with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole or clarithromycin. When the CYP3A4 inhibitor is withdrawn from the combination therapy, FANAPT dose should be increased to where it was before [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Dosage adjustment for patients taking FANAPT who are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6: FANAPT dose should be reduced by one-half for poor metabolizers of CYP2D6 [see Clinical Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics (12.3)].

Hepatic Impairment: No dose adjustment to FANAPT is needed in patients with mild hepatic impairment. Exercise caution when administering it to patients with moderate hepatic impairment. FANAPT is not recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment [see Use in Specific Populations (8.7)].

2.3 Maintenance Treatment

Although there is no body of evidence available to answer the question of how long the patient treated with FANAPT should be maintained, it is generally recommended that responding patients be continued beyond the acute response. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment.

2.4 Reinitiation of Treatment in Patients Previously Discontinued

Although there are no data to specifically address reinitiation of treatment, it is recommended that the initiation titration schedule be followed whenever patients have had an interval off FANAPT of more than 3 days.

2.5 Switching from Other Antipsychotics

There are no specific data to address how patients with schizophrenia can be switched from other antipsychotics to FANAPT or how FANAPT can be used concomitantly with other antipsychotics. Although immediate discontinuation of the previous antipsychotic treatment may be acceptable for some patients with schizophrenia, more gradual discontinuation may be most appropriate for others. In all cases, the period of overlapping antipsychotic administration should be minimized.

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

FANAPT is contraindicated in individuals with a known hypersensitivity reaction to the product. Anaphylaxis, angioedema, and other hypersensitivity reactions have been reported [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Risks in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Increased Mortality

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. FANAPT is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis[see Boxed Warning].

Cerebrovascular Adverse Events, Including Stroke

In placebo-controlled trials with risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine in elderly patients with dementia, there was a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events (cerebrovascular accidents and transient ischemic attacks) including fatalities compared to placebo-treated patients. FANAPT is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warning].

5.2 QT Prolongation

In an open-label QTc study in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (n=160), FANAPT was associated with QTc prolongation of 9 msec at an iloperidone dose of 12 mg twice daily. The effect of FANAPT on the QT interval was augmented by the presence of CYP450 2D6 or 3A4 metabolic inhibition (paroxetine 20 mg once daily and ketoconazole 200 mg twice daily, respectively). Under conditions of metabolic inhibition for both 2D6 and 3A4, FANAPT 12 mg twice daily was associated with a mean QTcF increase from baseline of about 19 msec.

No cases of torsade de pointes or other severe cardiac arrhythmias were observed during the pre-marketing clinical program.

The use of FANAPT should be avoided in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong QTc including Class 1A (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) or Class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic medications, antipsychotic medications (e.g., chlorpromazine, thioridazine), antibiotics (e.g., gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin), or any other class of medications known to prolong the QTc interval (e.g., pentamidine, levomethadyl acetate, methadone). FANAPT should also be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.

Certain circumstances may increase the risk of torsade de pointes and/or sudden death in association with the use of drugs that prolong the QTc interval, including (1) bradycardia; (2) hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia; (3) concomitant use of other drugs that prolong the QTc interval; and (4) presence of congenital prolongation of the QT interval; (5) recent acute myocardial infarction; and/or (6) uncompensated heart failure.

Caution is warranted when prescribing FANAPT with drugs that inhibit FANAPT metabolism [see Drug Interactions (7.1)], and in patients with reduced activity of CYP2D6 [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

It is recommended that patients being considered for FANAPT treatment who are at risk for significant electrolyte disturbances have baseline serum potassium and magnesium measurements with periodic monitoring. Hypokalemia (and/or hypomagnesemia) may increase the risk of QT prolongation and arrhythmia. FANAPT should be avoided in patients with histories of significant cardiovascular illness, e.g., QT prolongation, recent acute myocardial infarction, uncompensated heart failure, or cardiacarrhythmia. FANAPT should be discontinued in patients who are found to have persistent QTc measurements >500 msec.

If patients taking FANAPT experience symptoms that could indicate the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias, e.g., dizziness, palpitations, or syncope, the prescriber should initiate further evaluation, including cardiac monitoring.

5.3 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with administration of antipsychotic drugs, including FANAPT. Clinical manifestations include hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status (including catatonic signs) and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with this syndrome is complicated. In arriving at a diagnosis, it is important to identify cases in which the clinical presentation includes both serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection, etc.) and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal signs and symptoms (EPS). Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever, and primary central nervous system (CNS) pathology.

The management of this syndrome should include: (1) immediate discontinuation of the antipsychotic drugs and other drugs not essential to concurrent therapy, (2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring, and (3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for NMS.

If a patient requires antipsychotic drug treatment after recovery from NMS, the potential reintroduction of drug therapy should be carefully considered. The patient should be carefully monitored, since recurrences of NMS have been reported.

5.4 Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia is a syndrome consisting of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements, which may develop in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to rely on prevalence estimates to predict, at the inception of antipsychotic treatment, which patients are likely to develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible are believed to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose of antipsychotic administered increases. However, the syndrome can develop, although much less commonly, after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses.

There is no known treatment for established cases of tardive dyskinesia, although the syndrome may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn. Antipsychotic treatment itself, however, may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome and thereby may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, FANAPT should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who suffer from a chronic illness that (1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs, and (2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient on FANAPT, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment with FANAPT despite the presence of the syndrome.

5.5 Metabolic Changes

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and body weight gain [see Patient Counseling Information (17.3)]. While all atypical antipsychotic drugs have been shown to produce some metabolic changes, each drug in the class has its own specific risk profile.

Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, has been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics including FANAPT. Assessment of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and glucose abnormalities is complicated by the possibility of an increased background risk of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia and the increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus in the general population. Given these confounders, the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and hyperglycemia-related adverse events is not completely understood. However, epidemiological studies suggest an increased risk of treatment-emergent hyperglycemia-related adverse events in patients treated with the atypical antipsychotics included in these studies. Because FANAPT was not marketed at the time these studies were performed, it is not known if FANAPT is associated with this increased risk.

Patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of antidiabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the suspect drug.

Data from a 4-week, fixed-dose study in adult subjects with schizophrenia, in which fasting blood samples were drawn,are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Change in Fasting Glucose FANAPT Placebo 24 mg/day Mean Change from Baseline(mg/dL) n=114 n=228 Serum Glucose Change from Baseline -0.5 6.6 Proportion of Patients with Shifts Serum Glucose Normal to High 2.5 % 10.7 % (<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) (2/80) (18/169) Pooled analyses of glucose data from clinical studies including longer term trials are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Change in Glucose Mean Change from Baseline (mg/dL) 3-6 months 6-12 months >12 months FANAPT 10-16 mg/day 1.8 (N=773) 5.4 (N=723) 5.4 (N=425) FANAPT 20-24 mg/day -3.6 (N=34) -9.0 (N=31) -18.0 (N=20) Dyslipidemia

Undesirable alterations in lipids have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.

Data from a placebo-controlled, 4-week, fixed-dose study, in which fasting blood samples were drawn, in adult subjects with schizophrenia are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Change in Fasting Lipids FANAPT Placebo 24 mg/day Mean Change from Baseline (mg/dL) Cholesterol n= 114 n=228 Change from baseline -2.17 8.18 LDL n=109 n=217 Change from baseline -1.41 9.03 HDL n= 114 n=228 Change from baseline -3.35 0.55 Triglycerides n= 114 n=228 Change from baseline 16.47 -0.83 Proportion of Patients with Shifts Cholesterol Normal to High 1.4% 3.6% (<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) (1/72) (5/141) LDL Normal to High 2.4% 1.1% (<100 mg/dL to ≥160 mg/dL) (1/42) (1/90) HDL Normal to Low 23.8% 12.1% ( ≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL) (19/80) (20/166) Triglycerides Normal to High 8.3% 10.1% (<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) (6/72) (15/148) Pooled analyses of cholesterol and triglyceride data from clinical studies including longer term trials are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4: Change in Cholesterol Mean Change from Baseline (mg/dL) 3-6 months 6-12 months >12 months FANAPT 10-16 mg/day -3.9 (N=783) -3.9 (N=726) -7.7 (N=428) FANAPT 20-24 mg/day -19.4 (N=34) -23.2 (N=31) -19.4 (N=20) Table 5: Change in Triglycerides Mean Change from Baseline (mg/dL) 3-6 months 6-12 months >12 months FANAPT 10-16 mg/day -8.9 (N=783) -8.9 (N=726) -17.7 (N=428) FANAPT 20-24 mg/day -26.6 (N=34) -35.4 (N=31) -17.7 (N=20) Weight Gain

Weight gain has been observed with atypical antipsychotic use. Clinical monitoring of weight is recommended.

Across all short- and long-term studies, the overall mean change from baseline at endpoint was 2.1 kg.

Changes in body weight (kg) and the proportion of subjects with ≥7% gain in body weight from 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies in adult subjects are presented in Table 6.

Table 6: Change in Body Weight FANAPT FANAPT Placebo 10-16 mg/day 20-24 mg/day n=576 n=481 n=391 Weight (kg) Change from Baseline -0.1 2.0 2.7 Weight Gain ≥7% increase from Baseline 4% 12% 18% 5.6 Seizures

In short-term placebo-controlled trials (4- to 6-weeks), seizures occurred in 0.1% (1/1344) of patients treated with FANAPT compared to 0.3% (2/587) on placebo. As with other antipsychotics, FANAPT should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that potentially lower the seizure threshold, e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia. Conditions that lower the seizure threshold may be more prevalent in a population of 65 years or older.

5.7 Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

FANAPT can induce orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, tachycardia, and syncope. This reflects its alpha1-adrenergic antagonist properties. In double-blind placebo-controlled short-term studies, where the dose was increased slowly, as recommended above, syncope was reported in 0.4% (5/1344) of patients treated with FANAPT, compared with 0.2% (1/587) on placebo. Orthostatic hypotension was reported in 5% of patients given 20-24 mg/day, 3% of patients given 10-16 mg/day, and 1% of patients given placebo. More rapid titration would be expected to increase the rate of orthostatic hypotension and syncope.

FANAPT should be used with caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease (e.g., heart failure, history of myocardial infarction, ischemia, or conduction abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease, or conditions that predispose the patient to hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, and treatment with antihypertensive medications). Monitoring of orthostatic vital signs should be considered in patients who are vulnerable to hypotension.

5.8 Leukopenia, Neutropenia and Agranulocytosis

In clinical trial and postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia/neutropenia have been reported temporally related to antipsychotic agents. Agranulocytosis (including fatal cases) has also been reported.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include preexisting low white blood cell count (WBC) and history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Patients with a pre-existing low WBC or a history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and should discontinue FANAPT at the first sign of a decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors.

Patients with neutropenia should be carefully monitored for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treated promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3) should discontinue FANAPT and have their WBC followed until recovery.

5.9 Hyperprolactinemia

As with other drugs that antagonize dopamine D2 receptors, FANAPT elevates prolactin levels.

Hyperprolactinemia may suppress hypothalamicGnRH, resulting in reduced pituitary gonadotropin secretion. This, in turn, may inhibit reproductive function by impairing gonadalsteroidogenesis in both female and male patients. Galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence have been reported with prolactin-elevating compounds. Long-standing hyperprolactinemia when associated with hypogonadism may lead to decreased bone density in both female and male patients.

Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin-dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if the prescription of these drugs is contemplated in a patient with previously detected breast cancer. Mammary gland proliferative changes and increases in serum prolactin were seen in mice and rats treated with FANAPT [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)]. Neither clinical studies nor epidemiologic studies conducted to date have shown an association between chronic administration of this class of drugs and tumorigenesis in humans; the available evidence is considered too limited to be conclusive at this time.

In a short-term placebo-controlled trial (4-weeks), the mean change from baseline to endpoint in plasma prolactin levels for the FANAPT 24 mg/day-treated group was an increase of 2.6 ng/mL compared to a decrease of 6.3 ng/mL in the placebo-group. In this trial, elevated plasma prolactin levels were observed in 26% of adults treated with FANAPT compared to 12% in the placebo group. In the short-term trials, FANAPT was associated with modest levels of prolactin elevation compared to greater prolactin elevations observed with some other antipsychotic agents. In pooled analysis from clinical studies including longer term trials, in 3210 adults treated with iloperidone, gynecomastia was reported in 2 male subjects (0.1%) compared to 0% in placebo-treated patients, and galactorrhea was reported in 8 female subjects (0.2%) compared to 3 female subjects (0.5%) in placebo-treated patients.

5.10 Body Temperature Regulation

Disruption of the body’s ability to reduce core body temperature has been attributed to antipsychotic agents. Appropriate care is advised when prescribing FANAPT for patients who will be experiencing conditions which may contribute to an elevation in core body temperature, e.g., exercising strenuously, exposure to extreme heat, receiving concomitant medication with anticholinergic activity, or being subject to dehydration.

5.11 Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use. Aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients, in particular those with advanced Alzheimer’s dementia. FANAPT and other antipsychotic drugs should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia [see Boxed Warning].

5.12 Suicide

The possibility of a suicide attempt is inherent in psychotic illness, and close supervision of high-risk patients should accompany drug therapy. Prescriptions for FANAPT should be written for the smallest quantity of tablets consistent with good patient management in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

5.13 Priapism

Three cases of priapism were reported in the pre-marketing FANAPT program. Drugs with alpha-adrenergic blocking effects have been reported to induce priapism. FANAPT shares this pharmacologic activity. Severe priapism may require surgical intervention.

5.14 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

FANAPT, like other antipsychotics, has the potential to impair judgment, thinking or motor skills. In short-term, placebo-controlled trials, somnolence (including sedation) was reported in 11.9% (104/874) of adult patients treated with FANAPTat doses of 10 mg/day or greater versus 5.3% (31/587) treated with placebo. Patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that therapy with FANAPT does not affect them adversely.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Studies Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trial of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in clinical practice. The information below is derived from a clinical trial database for FANAPT consisting of 2070 patients exposed to FANAPT at doses of 10 mg/day or greater, for the treatment of schizophrenia. Of these, 806 received FANAPT for at least 6 months, with 463 exposed to FANAPT for at least 12 months. All of these patients who received FANAPT were participating in multiple-dose clinical trials. The conditions and duration of treatment with FANAPT varied greatly and included (in overlapping categories), open-label and double-blind phases of studies, inpatients and outpatients, fixed-dose and flexible-dose studies, and short-term and longer-term exposure.

Adverse reactions during exposure were obtained by general inquiry and recorded by clinical investigators using their own terminology. Consequently, to provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing adverse reactions, reactions were grouped in standardized categories using MedDRA terminology.

The stated frequencies of adverse reactions represent the proportions of individuals who experienced a treatment-emergent adverse reaction of the type listed. A reaction was considered treatment emergent if it occurred for the first time or worsened while receiving therapy following baseline evaluation.

The information presented in these sections was derived from pooled data from 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies in patients who received FANAPT at daily doses within a range of 10 to 24 mg (n=874).

Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 2% or More among FANAPT-Treated Patientsand More Frequent than Placebo

Table 7 enumerates the pooled incidences of treatment-emergent adverse reactions that were spontaneously reported in four placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies, listing those reactions that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with FANAPT in any of the dose groups, and for which the incidence in FANAPT-treated patients in any dose group was greater than the incidence in patients treated with placebo.

Table 7: Percentage of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Fixed- or Flexible-Dose, Placebo-Controlled Trials in Adult Patients* Body System or Organ Class Placebo

(%)FANAPT 10-16 mg/day

(%)FANAPT 20-24 mg/day

(%)Dictionary-derived Term (N=587) (N=483) (N=391) Body as a Whole Arthralgia 2 3 3 Fatigue 3 4 6 Musculoskeletal Stiffness 1 1 3 Weight Increased 1 1 9 Cardiac Disorders Tachycardia 1 3 12 Eye Disorders Vision Blurred 2 3 1 Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea 8 7 10 Dry Mouth 1 8 10 Diarrhea 4 5 7 Abdominal Discomfort 1 1 3 Infections Nasopharyngitis 3 4 3 Upper Respiratory Tract Infection 1 2 3 Nervous System Disorders Dizziness 7 10 20 Somnolence 5 9 15 Extrapyramidal Disorder 4 5 4 Tremor 2 3 3 Lethargy 1 3 1 Reproductive System Ejaculation Failure <1 2 2 Respiratory Nasal Congestion 2 5 8 Dyspnea <1 2 2 Skin Rash 2 3 2 Vascular Disorders Orthostatic Hypotension 1 3 5 Hypotension <1 <1 3 * Table includes adverse reactions that were reported in 2% or more of patients in any of the FANAPT dose groups and which occurred at greater incidence than in the placebo group. Figures rounded to the nearest integer.

Dose-Related Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials

Based on the pooled data from 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies, adverse reactions that occurred with a greater than 2% incidence in the patients treated with FANAPT, and for which the incidence in patients treated with FANAPT20-24 mg/day were twice than the incidence in patients treated with FANAPT 10-16 mg/day were: abdominal discomfort, dizziness, hypotension, musculoskeletal stiffness, tachycardia, and weight increased.

Common and Drug-Related Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials

Based on the pooled data from 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies, the following adverse reactions occurred in ≥5% incidence in the patients treated with FANAPT and at least twice the placebo rate for at least 1 dose: dizziness, dry mouth, fatigue, nasal congestion, somnolence, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and weight increased. Dizziness, tachycardia, and weight increased were at least twice as common on 20-24 mg/day as on 10-16 mg/day.

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS) in Clinical Trials

Pooled data from the 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies provided information regarding treatment-emergent EPS. Adverse event data collected from those trials showed the following rates of EPS-related adverse events as shown in Table 8.

Table 8: Percentage of EPS Compared to Placebo Placebo

(%)FANAPT 10-16 mg/day

(%)FANAPT 20-24 mg/day

(%)Adverse Event Term (N=587) (N=483) (N=391) All EPS events 11.6 13.5 15.1 Akathisia 2.7 1.7 2.3 Bradykinesia 0 0.6 0.5 Dyskinesia 1.5 1.7 1.0 Dystonia 0.7 1.0 0.8 Parkinsonism 0 0.2 0.3 Tremor 1.9 2.5 3.1 Adverse Reactions Associated with Discontinuation of Treatment in Clinical Trials

Based on the pooled data from 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies, there was no difference in the incidence of discontinuation due to adverse events between FANAPT-treated (5%) and placebo-treated (5%) patients. The types of adverse events that led to discontinuation were similar for the FANAPT- and placebo-treated patients.

Demographic Differences in Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials

An examination of population subgroups in the 4 placebo-controlled, 4- or 6-week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies did not reveal any evidence of differences in safety on the basis of age, gender or race [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Laboratory Test Abnormalities in Clinical Trials

There were no differences between FANAPT and placebo in the incidence of discontinuation due to changes in hematology, urinalysis, or serum chemistry.

In short-term placebo-controlled trials (4- to 6-weeks), there were 1.0% (13/1342) iloperidone-treated patients with hematocrit at least one time below the extended normal range during post-randomization treatment, compared to 0.3% (2/585) on placebo. The extended normal range for lowered hematocrit was defined in each of these trials as the value 15% below the normal range for the centralized laboratory that was used in the trial.

Other Reactions During the Pre-marketing Evaluation of FANAPT

The following is a list of MedDRA terms that reflect treatment-emergent adverse reactions in patients treated with FANAPT at multiple doses ≥ 4 mg/day during any phase of a trial with the database of 3210 FANAPT-treated patients. All reported reactions are included except those already listed in Table 7, or other parts of the Adverse Reactions (6) section, those considered in the Warnings and Precautions (5), those reaction terms which were so general as to be uninformative, reactions reported in fewer than 3 patients and which were neither serious nor life-threatening, reactions that are otherwise common as background reactions, and reactions considered unlikely to be drug related. It is important to emphasize that, although the reactions reported occurred during treatment with FANAPT, they were not necessarily caused by it.

Reactions are further categorized by MedDRA system organ class and listed in order of decreasing frequency according to the following definitions: frequent adverse events are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients (only those not listed in Table 7 appear in this listing); infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare events are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Blood and Lymphatic Disorders: Infrequent – anemia, iron deficiency anemia; Rare – leukopenia

Cardiac Disorders: Frequent – palpitations; Rare – arrhythmia, atrioventricular block first degree, cardiac failure (including congestive and acute)

Ear and Labyrinth Disorders: Infrequent – vertigo, tinnitus

Endocrine Disorders: Infrequent – hypothyroidism

Eye Disorders: Frequent - conjunctivitis (including allergic); Infrequent – dry eye, blepharitis, eyelid edema, eye swelling, lenticular opacities, cataract, hyperemia (including conjunctival)

Gastrointestinal Disorders: Infrequent – gastritis, salivary hypersecretion, fecal incontinence, mouth ulceration; Rare - aphthous stomatitis, duodenal ulcer, hiatus hernia, hyperchlorhydria, lip ulceration, reflux esophagitis, stomatitis

General Disorders and Administrative Site Conditions: Infrequent – edema (general, pitting, due to cardiac disease), difficulty in walking, thirst; Rare - hyperthermia

Hepatobiliary Disorders: Infrequent – cholelithiasis

Investigations: Frequent: weight decreased; Infrequent – hemoglobin decreased, neutrophil count increased, hematocrit decreased

Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders:Infrequent – increased appetite, dehydration, hypokalemia, fluid retention

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: Frequent – myalgia, muscle spasms; Rare – torticollis

Nervous System Disorders: Infrequent – paresthesia, psychomotor hyperactivity, restlessness, amnesia, nystagmus; Rare – restless legs syndrome

Psychiatric Disorders: Frequent – restlessness, aggression, delusion; Infrequent – hostility, libido decreased, paranoia, anorgasmia, confusional state, mania, catatonia, mood swings, panic attack, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bulimia nervosa, delirium, polydipsia psychogenic, impulse-control disorder, major depression

Renal and Urinary Disorders: Frequent – urinary incontinence; Infrequent – dysuria, pollakiuria, enuresis, nephrolithiasis; Rare – urinary retention, renal failure acute

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: Frequent – erectile dysfunction; Infrequent – testicular pain, amenorrhea, breast pain; Rare – menstruation irregular, gynecomastia, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, postmenopausal hemorrhage, prostatitis.

Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders: Infrequent – epistaxis, asthma, rhinorrhea, sinus congestion, nasal dryness; Rare – dry throat, sleep apnea syndrome, dyspnea exertional

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of FANAPT: retrograde ejaculation and hypersensitivity reactions (including anaphylaxis; angioedema; throat tightness; oropharyngeal swelling; swelling of the face, lips, mouth, and tongue; urticaria; rash; and pruritus). Because these reactions were reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

Given the primary CNS effects of FANAPT, caution should be used when it is taken in combination with other centrally acting drugs and alcohol. Due to its - alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonism, FANAPT has the potential to enhance the effect of certain antihypertensive agents.

7.1 Potential for Other Drugs to Affect FANAPT

Iloperidone is not a substrate for CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, or CYP2E1 enzymes. This suggests that an interaction of iloperidone with inhibitors or inducers of these enzymes, or other factors, like smoking, is unlikely.

Both CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 are responsible for iloperidone metabolism. Inhibitors of CYP3A4 (e.g., ketoconazole) or CYP2D6 (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine) can inhibit iloperidone elimination and cause increased blood levels.

Ketoconazole: Co-administration of ketoconazole (200 mg twice daily for 4 days), a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, with a 3 mg single dose of iloperidone to 19 healthy volunteers, ages 18-45 years, increased the area under the curve (AUC) of iloperidone and its metabolites P88 and P95 by 57%, 55% and 35%, respectively. Iloperidone doses should be reduced by about one-half when administered with ketoconazole or other strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (e.g., itraconazole). Weaker inhibitors (e.g., erythromycin, grapefruit juice) have not been studied. When the CYP3A4 inhibitor is withdrawn from the combination therapy, the iloperidone dose should be returned to the previous level.

Fluoxetine: Coadministration of fluoxetine (20 mg twice daily for 21 days), a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6, with a single 3 mg dose of iloperidone to 23 healthy volunteers, ages 29-44 years, who were classified as CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers, increased the AUC of iloperidone and its metabolite P88, by about 2- to 3-fold, and decreased the AUC of its metabolite P95 by one-half. Iloperidone doses should be reduced by one-half when administered with fluoxetine. When fluoxetine is withdrawn from the combination therapy, the iloperidone dose should be returned to the previous level. Other strong inhibitors of CYP2D6 would be expected to have similar effects and would need appropriate dose reductions. When the CYP2D6 inhibitor is withdrawn from the combination therapy, iloperidone dose could then be increased to the previous level.

Paroxetine: Coadministration of paroxetine (20 mg/day for 5-8 days), a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6, with multiple doses of iloperidone (8 or 12 mg twice daily) to patients with schizophrenia ages 18-65 years resulted in increased mean steady-state peak concentrations of iloperidone and its metabolite P88, by about 1.6 fold, and decreased mean steady-state peak concentrations of its metabolite P95 by one-half. Iloperidone doses should be reduced by one-half when administered with paroxetine. When paroxetine is withdrawn from the combination therapy, the iloperidone dose should be returned to the previous level. Other strong inhibitors of CYP2D6 would be expected to have similar effects and would need appropriate dose reductions. When the CYP2D6 inhibitor is withdrawn from the combination therapy, iloperidone dose could then be increased to previous levels.

Paroxetine and Ketoconazole:Coadministration of paroxetine (20 mg once daily for 10 days), a CYP2D6 inhibitor, and ketoconazole (200 mg twice daily) with multiple doses of iloperidone (8 or 12 mg twice daily) to patients with schizophrenia ages 18-65 years resulted in a 1.4 fold increase in steady-state concentrations of iloperidone and its metabolite P88 and a 1.4 fold decrease in the P95 in the presence of paroxetine. So giving iloperidone with inhibitors of both of its metabolic pathways did not add to the effect of either inhibitor given alone. Iloperidone doses should therefore be reduced by about one-half if administered concomitantly with both a CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 inhibitor.

7.2 Potential for FANAPT to Affect Other Drugs

In vitro studies in human liver microsomes showed that iloperidone does not substantially inhibit the metabolism of drugs metabolized by the following cytochrome P450 isozymes: CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, or CYP2E1. Furthermore, in vitro studies in human liver microsomes showed that iloperidone does not have enzyme inducing properties, specifically for the following cytochrome P450 isozymes: CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5.

Dextromethorphan: A study in healthy volunteers showed that changes in the pharmacokinetics of dextromethorphan (80 mg dose) when a 3 mg dose of iloperidone was co-administered resulted in a 17% increase in total exposure and a 26% increase in the maximum plasma concentrations Cmax of dextromethorphan. Thus, an interaction between iloperidone and other CYP2D6 substrates is unlikely.

Fluoxetine: A single 3 mg dose of iloperidone had no effect on the pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine (20 mg twice daily).

Midazolam (a sensitive CYP 3A4 substrate): A study in patients with schizophrenia showed a less than 50% increase in midazolam total exposure at iloperidone steady state (14 days of oral dosing at up to 10 mg iloperidone twice daily) and no effect on midazolam Cmax. Thus, an interaction between iloperidone and other CYP3A4 substrates is unlikely.

7.3 Drugs that Prolong the QT Interval

FANAPT should not be used with any other drugs that prolong the QT interval [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C

FANAPT caused developmental toxicity, but was not teratogenic, in rats and rabbits.

In an embryo-fetal development study, pregnant rats were given 4, 16, or 64 mg/kg/day (1.6, 6.5, and 26 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 24 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis) of iloperidone orally during the period of organogenesis. The highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths, decreased fetal weight and length, decreased fetal skeletal ossification, and an increased incidence of minor fetal skeletal anomalies and variations; this dose also caused decreased maternal food consumption and weight gain.

In an embryo-fetal development study, pregnant rabbits were given 4, 10, or 25 mg/kg/day (3, 8, and 20 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) of iloperidone during the period of organogenesis. The highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths and decreased fetal viability at term; this dose also caused maternal toxicity.

In additional studies in which rats were given iloperidone at doses similar to the above beginning from either pre-conception or from day 17 of gestation and continuing through weaning, adverse reproductive effects included prolonged pregnancy and parturition, increased stillbirth rates, increased incidence of fetal visceral variations, decreased fetal and pup weights, and decreased post-partum pup survival. There were no drug effects on the neurobehavioral or reproductive development of the surviving pups. No-effect doses ranged from 4 to 12 mg/kg except for the increase in stillbirth rates which occurred at the lowest dose tested of 4 mg/kg, which is 1.6 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. Maternal toxicity was seen at the higher doses in these studies.

The iloperidone metabolite P95, which is a major circulating metabolite of iloperidone in humans but is not present in significant amounts in rats, was given to pregnant rats during the period of organogenesis at oral doses of 20, 80, or 200 mg/kg/day. No teratogenic effects were seen. Delayed skeletal ossification occurred at all doses. No significant maternal toxicity was produced. Plasma levels of P95 (AUC) at the highest dose tested were 2 times those in humans receiving the MRHD of iloperidone.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women.

Non-teratogenic Effects

Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs, during the third trimester of pregnancy are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery. There have been reports of agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress and feeding disorder in these neonates. These complications have varied in severity; while in some cases symptoms have been self-limited, in other cases neonates have required intensive care unit support and prolonged hospitalization.

FANAPT should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

FANAPT was excreted in milk of rats during lactation. It is not known whether FANAPT or its metabolites are excreted in human milk. It is recommended that women receiving FANAPT should not breast-feed.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric and adolescent patients have not been established.

8.5 Geriatric Use

Clinical Studies of FANAPT in the treatment of schizophrenia did not include sufficient numbers of patients aged 65 years and over to determine whether or not they respond differently than younger adult patients. Of the 3210 patients treated with FANAPT in premarketing trials, 25 (0.5%) were ≥65 years old and there were no patients ≥75 years old.

Studies of elderly patients with psychosis associated with Alzheimer’s disease have suggested that there may be a different tolerability profile (i.e., increased risk in mortality and cerebrovascular events including stroke) in this population compared to younger patients with schizophrenia [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]. The safety and efficacy of FANAPT in the treatment of patients with psychosis associated with Alzheimer’s disease has not been established. If the prescriber elects to treat such patients with FANAPT, vigilance should be exercised.

8.6 Renal Impairment

Because FANAPT is highly metabolized, with less than 1% of the drug excreted unchanged, renal impairment alone is unlikely to have a significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of FANAPT. Renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) had minimal effect on Cmax of iloperidone (given in a single dose of 3 mg) and its metabolites P88 and P95 in any of the 3analytes measured. AUC0–∞ was increased by 24%, decreased by 6%, and increased by 52% for iloperidone, P88 and P95, respectively, in subjects with renal impairment.

8.7 Hepatic Impairment

No dose adjustment to FANAPT is needed in patients with mild hepatic impairment. Exercise caution when administering it to patients with moderate hepatic impairment. FANAPT is not recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment [see Dosage in Special Populations (2.2)].

In adult subjects with mild hepatic impairment no relevant difference in pharmacokinetics of iloperidone, P88 or P95 (total or unbound) was observed compared to healthy adult controls. In subjects with moderate hepatic impairment a higher (2-fold) and more variable free exposure to the active metabolites P88 was observed compared to healthy controls, whereas exposure to iloperidone and P95 was generally similar (less than 50% change compared to control). Since a study in severe liver impaired subjects has not been conducted, FANAPT is not recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment.

-

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

FANAPT has not been systematically studied in animals or humans for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. While the clinical trials did not reveal any tendency for drug-seeking behavior, these observations were not systematic and it is not possible to predict on the basis of this experience the extent to which a CNS active drug, FANAPT, will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, patients should be evaluated carefully for a history of drug abuse, and such patients should be observed closely for signs of FANAPT misuse or abuse (e.g. development of tolerance, increases in dose, drug-seeking behavior).

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

In pre-marketing trials involving over 3210 patients, accidental or intentional overdose of FANAPT was documented in 8 patients ranging from 48 mg to 576 mg taken at once and 292 mg taken over a 3-day period. No fatalities were reported from these cases. The largest confirmed single ingestion of FANAPT was 576 mg; no adverse physical effects were noted for this patient. The next largest confirmed ingestion of FANAPT was 438 mg over a 4-day period; extrapyramidal symptoms and a QTc interval of 507 msec were reported for this patient with no cardiac sequelae. This patient resumed FANAPT treatment for an additional 11 months. In general, reported signs and symptoms were those resulting from an exaggeration of the known pharmacological effects (e.g., drowsiness and sedation, tachycardia and hypotension) of FANAPT.

10.2 Management of Overdose

There is no specific antidote for FANAPT. Therefore appropriate supportive measures should be instituted. In case of acute overdose, the physician should establish and maintain an airway and ensure adequate oxygenation and ventilation. Gastric lavage (after intubation, if patient is unconscious) and administration of activated charcoal together with a laxative should be considered. The possibility of obtundation, seizures or dystonic reaction of the head and neck following overdose may create a risk of aspiration with induced emesis. Cardiovascular monitoring should commence immediately and should include continuous ECG monitoring to detect possible arrhythmias. If antiarrhythmic therapy is administered, disopyramide, procainamide and quinidine should not be used, as they have the potential for QT-prolonging effects that might be additive to those of FANAPT. Similarly, it is reasonable to expect that the alpha-blocking properties of bretylium might be additive to those of FANAPT, resulting in problematic hypotension. Hypotension and circulatory collapse should be treated with appropriate measures such as intravenous fluids or sympathomimetic agents (epinephrine and dopamine should not be used, since beta stimulation may worsen hypotension in the setting of FANAPT-induced alpha blockade). In cases of severe extrapyramidal symptoms, anticholinergic medication should be administered. Close medical supervision should continue until the patient recovers.

-

11 DESCRIPTION

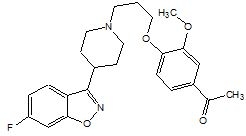

FANAPT is a psychotropic agent belonging to the chemical class of piperidinyl-benzisoxazole derivatives. Its chemical name is 4’-[3-[4-(6-Fluoro-1,2-benzisoxazol-3-yl)piperidino]propoxy]-3’-methoxyacetophenone. Its molecular formula is C24H27FN2O4 and its molecular weight is 426.48. The structural formula is:

Iloperidone is a white to off-white finely crystalline powder. It is practically insoluble in water, very slightly soluble in 0.1 N HCl and freely soluble in chloroform, ethanol, methanol, and acetonitrile.

FANAPT tablets are intended for oral administration only. Each round, uncoated tablet contains 1 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg, 6 mg, 8 mg, 10 mg, or 12 mg of iloperidone. Inactive ingredients are: lactose monohydrate, microcrystalline cellulose, hydroxypropylmethylcellulose, crospovidone, magnesium stearate, colloidal silicon dioxide, and purified water (removed during processing). The tablets are white, round, flat, beveled-edged and identified with a logo “

” debossed on one side and tablet strength “1”, “2”, “4”, “6”, “8”, “10”, or “12” debossed on the other side.

” debossed on one side and tablet strength “1”, “2”, “4”, “6”, “8”, “10”, or “12” debossed on the other side. -

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of FANAPT, as with other drugs having efficacy in schizophrenia, is unknown. However it is proposed that the efficacy of FANAPT is mediated through a combination of dopamine type 2 (D2) and serotonin type 2 (5-HT2) antagonisms.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

FANAPT exhibits high (nM) affinity binding to serotonin 5-HT2Adopamine D2 and D3 receptors, and norepinephrine NEα1 receptors (Ki values of 5.6, 6.3, 7.1, and 0.36 nM, respectively). FANAPT has moderate affinity for dopamine D4, and serotonin 5-HT6 and 5-HT7receptors (Ki values of 25, 43, and 22, nM respectively), and low affinity for the serotonin 5-HT1A, dopamine D1, and histamine H1 receptors (Ki values of 168, 216 and 437 nM, respectively). FANAPT has no appreciable affinity (Ki >1000 nM) for cholinergic muscarinic receptors. FANAPT functions as an antagonist at the dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A and norepinephrine α1/α2C receptors. The affinity of the FANAPT metabolite P88 is generally equal or less than that of the parent compound. In contrast, the metabolite P95 only shows affinity for 5-HT2A (Ki value of 3.91) and the NEα1A, NEα1B, NEα1D, and NEα2C receptors (Ki values of 4.7, 2.7, 8.8 and 4.7 nM respectively).

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The observed mean elimination half-lives for iloperidone, P88 and P95 in CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers (EM) are 18, 26, and 23 hours, respectively, and in poor metabolizers (PM) are 33, 37 and 31 hours, respectively. Steady-state concentrations are attained within 3-4 days of dosing. Iloperidone accumulation is predictable from single-dose pharmacokinetics. The pharmacokinetics of iloperidone is more than dose proportional. Elimination of iloperidone is mainly through hepatic metabolism involving 2 P450 isozymes, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.

Absorption: Iloperidone is well absorbed after administration of the tablet with peak plasma concentrations occurring within 2 to 4 hours; while the relative bioavailability of the tablet formulation compared to oral solution is 96%. Administration of iloperidone with a standard high-fat meal did not significantly affect the Cmax or AUC of iloperidone, P88, or P95, but delayed Tmax by 1 hour for iloperidone, 2 hours for P88 and 6 hours for P95. FANAPT can be administered without regard to meals.

Distribution: Iloperidone has an apparent clearance (clearance/bioavailability) of 47 to 102 L/h, with an apparent volume of distribution of 1340-2800 L. At therapeutic concentrations, the unbound fraction of iloperidone in plasma is ~3% and of each metabolite (P88 and P95) it is ~8%.

Metabolism and Elimination:Iloperidone is metabolized primarily by 3 biotransformation pathways: carbonyl reduction, hydroxylation (mediated by CYP2D6) and O-demethylation (mediated by CYP3A4). There are 2 predominant iloperidone metabolites, P95 and P88. The iloperidone metabolite P95 represents 47.9% of the AUC of iloperidone and its metabolites in plasma at steady-state for extensive metabolizers (EM) and 25% for poor metabolizers (PM). The active metabolite P88 accounts for 19.5% and 34.0% of total plasma exposure in EM and PM, respectively.

Approximately 7% - 10% of Caucasians and 3% - 8% of black/African Americans lack the capacity to metabolize CYP2D6 substrates and are classified as poor metabolizers (PM), whereas the rest are intermediate, extensive or ultrarapid metabolizers. Coadministration of FANAPT with known strong inhibitors of CYP2D6 like fluoxetine results in a 2.3-fold increase in iloperidone plasma exposure, and therefore one-half of the FANAPT dose should be administered.

Similarly, PMs of CYP2D6 have higher exposure to iloperidone compared with EMs and PMs should have their dose reduced by one-half. Laboratory tests are available to identify CYP2D6 PMs.

The bulk of the radioactive materials were recovered in the urine (mean 58.2% and 45.1% in EM and PM, respectively), with feces accounting for 19.9% (EM) to 22.1% (PM) of the dosed radioactivity.

Transporter Interaction: Iloperidone and P88 are not substrates of P-gp and iloperidone is a weak P-gp inhibitor.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis: Lifetime carcinogenicity studies were conducted in CD-1 mice and Sprague Dawley rats. Iloperidone was administered orally at doses of 2.5, 5.0 and 10 mg/kg/day to CD-1 mice and 4, 8, and 16 mg/kg/day to Sprague Dawley rats (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 times and 1.6, 3.2 and 6.5 times, respectively, the MRHD of 24 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis). There was an increased incidence of malignant mammary gland tumors in female mice treated with the lowest dose (2.5 mg/kg/day) only. There were no treatment-related increases in neoplasia in rats.

The carcinogenic potential of the iloperidone metabolite P95, which is a major circulating metabolite of iloperidone in humans but is not present at significant amounts in mice or rats, was assessed in a lifetime carcinogenicity study in Wistar rats at oral doses of 25, 75 and 200 mg/kg/day in males and 50, 150, and 250 (reduced from 400) mg/kg/day in females.

Drug-related neoplastic changes occurred in males, in the pituitary gland (pars distalis adenoma) at all doses and in the pancreas (islet cell adenoma) at the high dose. Plasma levels of P95 (AUC) in males at the tested doses (25, 75, and 200 mg/kg/day) were approximately 0.4, 3, and 23 times, respectively, the human exposure to P95 at the MRHD of iloperidone.

An increase in mammary, pituitary and endocrine pancreas neoplasms has been found in rodents after chronic administration of other antipsychotic drugs and is considered to be mediated by prolonged dopamine D2 antagonism and hyperprolactinemia. Increases in serum prolactin were seen in mice and rats treated with iloperidone. The relevance of these tumor findings in rodents in terms of human risk is unknown.

Mutagenesis: Iloperidone was negative in the Ames test and in the in vivo mouse bone marrow and rat liver micronucleus tests. Iloperidone induced chromosomal aberrations in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells in vitro at concentrations which also caused some cytotoxicity.

The iloperidone metabolite P95 was negative in the Ames test, the V79 chromosome aberration test, and an in vivo mouse bone marrow micronucleus test.

Impairment of Fertility: Iloperidone decreased fertility at 12 and 36 mg/kg in a study in which both male and female rats were treated. The no-effect dose was 4 mg/kg, which is 1.6 times the MRHD of 24 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis.

-

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

The efficacy of FANAPT in the treatment of schizophrenia was supported by 2 placebo- and active-controlled short-term (4- and 6-week) trials. Both trials enrolled patients who met the DSM-III/IV criteria for schizophrenia.

Two instruments were used for assessing psychiatric signs and symptoms in these studies. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) are both multi-item inventories of general psychopathology usually used to evaluate the effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia.

A 6-week, placebo-controlled trial (n=706) involved 2 flexible dose ranges of FANAPT (12-16 mg/day or 20-24 mg/day) compared to placebo and an active control (risperidone). For the 12-16 mg/day group, the titration schedule of FANAPT was 1 mg twice daily on Days 1 and 2, 2 mg twice daily on Days 3 and 4, 4 mg twice daily on Days 5 and 6, and 6 mg twice daily on Day 7. For the 20-24 mg/day group, the titration schedule of FANAPT was 1 mg twice daily on Day 1, 2 mg twice daily on Day 2, 4 mg twice daily on Day 3, 6 mg twice daily on Days 4 and 5, 8 mg twice daily on Day 6, and 10 mg twice daily on Day 7. The primary endpoint was change from baseline on the BPRS total score at the end of treatment (Day 42). Both the 12-16 mg/day and the 20-24 mg/day dose ranges of FANAPT were superior to placebo on the BPRS total score. The active control antipsychotic drug appeared to be superior to FANAPT in this trial within the first 2 weeks, a finding that may in part be explained by the more rapid titration that was possible for that drug. In patients in this study who remained on treatment for at least 2 weeks, iloperidone appeared to have had comparable efficacy to the active control.

A 4-week, placebo-controlled trial (n=604) involved one fixed dose of FANAPT (24 mg/day) compared to placebo and an active control (ziprasidone). The titration schedule for this study was similar to that for the 6-week study. This study involved titration of FANAPT starting at 1 mg twice daily on Day 1 and increasing to 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 mg twice daily on Days 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. The primary endpoint was change from baseline on the PANSS total score at the end of treatment (Day 28). The 24 mg/day FANAPT dose was superior to placebo in the PANSS total score. FANAPT appeared to have similar efficacy to the active control drug which also needed a slow titration to the target dose.

-

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

FANAPT tablets are white, round and identified with a logo “

” debossed on one side and tablet strength “4” debossed on the other side. Tablets are supplied in the following strengths and package configurations:

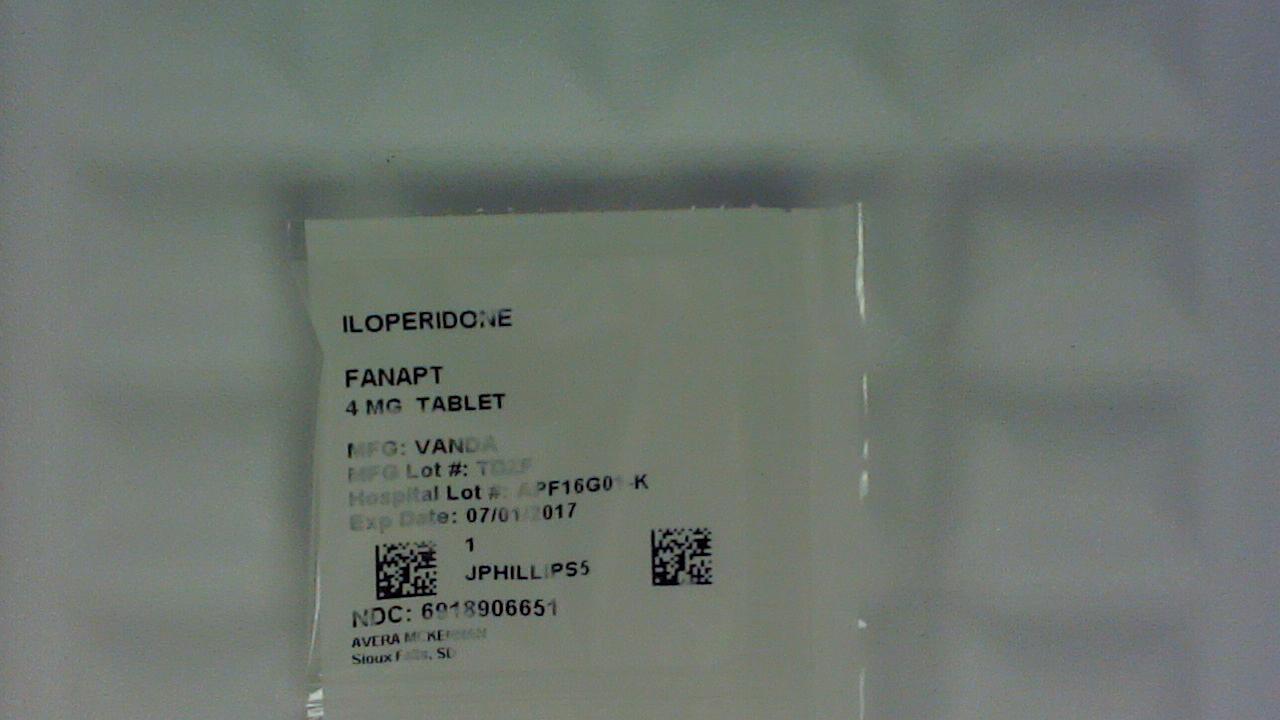

” debossed on one side and tablet strength “4” debossed on the other side. Tablets are supplied in the following strengths and package configurations:NDC 69189-0665-1 single dose pack with 1 tablet as repackaged by Avera McKennan Hospital

Package Configuration Tablet Strength (mg) NDC Code Bottles of 60 4 mg 43068-104-02 Storage

Store FANAPT tablets at controlled room temperature, 25°C (77°F); excursions permitted to 15°to 30 °C (59° to 86°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Protect FANAPT tablets from exposure to light and moisture.

-

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Physicians are advised to discuss the following issues with patients for whom they prescribe FANAPT:

17.1 QT Interval Prolongation

Patients should be advised to consult their physician immediately if they feel faint, lose consciousness or have heart palpitations. Patients should be counseled not to take FANAPT with other drugs that cause QT interval prolongation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. Patients should be told to inform physicians that they are taking FANAPT before any new drug is taken.

17.2 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Patients and caregivers should be counseled that a potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as NMS has been reported in association with administration of antipsychotic drugs, including FANAPT. Signs and symptoms of NMS include hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

17.3 Metabolic Changes

Patients should be aware of the symptoms of hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and diabetes mellitus. Patients who are diagnosed with diabetes, those with risk factors for diabetes, or those who develop these symptoms during treatment should have their blood glucose monitored at the beginning of and periodically during treatment. Patients should be counseled that weight gain has occurred during treatment with FANAPT. Clinical monitoring of weight is recommended. [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

17.4 Orthostatic Hypotension

Patients should be advised of the risk of orthostatic hypotension, particularly at the time of initiating treatment, re-initiating treatment, or increasing the dose [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

17.5 Interference with Cognitive and Motor Performance

Because FANAPT may have the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that FANAPT therapy does not affect them adversely [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14)].

17.6 Pregnancy

Patients should be advised to notify their physician if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy with FANAPT [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

17.7 Nursing

Patients should be advised not to breastfeed an infant if they are taking FANAPT [see Use in Specific Populations (8.3)].

17.8 Concomitant Medication

Patients should be advised to inform their physicians if they are taking, or plan to take, any prescription or over-the-counter drugs, since there is a potential for interactions [see Drug Interactions (7)].

17.10 Heat Exposure and Dehydration

Patients should be advised regarding appropriate care in avoiding overheating and dehydration.

Distributed by:

Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Washington, D.C. 20037 USA

Vanda and Fanapt® are registered trademarks of Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. in the United States and other countries.

January 2016

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

FANAPT

iloperidone tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 69189-0665(NDC:43068-104) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ILOPERIDONE (UNII: VPO7KJ050N) (ILOPERIDONE - UNII:VPO7KJ050N) ILOPERIDONE 4 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) CROSPOVIDONE (UNII: 2S7830E561) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) Product Characteristics Color WHITE Score no score Shape ROUND (flat, beveled-edge) Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code 4 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 69189-0665-1 1 in 1 DOSE PACK; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 07/01/2016 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA NDA022192 07/01/2016 Labeler - Avera McKennan Hospital (068647668) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Avera McKennan Hospital 068647668 relabel(69189-0665) , repack(69189-0665)

Trademark Results [Fanapt]

Mark Image Registration | Serial | Company Trademark Application Date |

|---|---|

FANAPT 77512787 3870927 Live/Registered |

Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2008-07-01 |

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.