CYMBALTA- duloxetine hydrochloride capsule, delayed release

Cymbalta by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Cymbalta by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by REMEDYREPACK INC.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use CYMBALTA safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for CYMBALTA.

CYMBALTA (Duloxetine Delayed-Release Capsules) for Oral Use.

Initial U.S. Approval: 2004WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

Warnings and Precautions ( 5.5) 10/2019 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

- Take CYMBALTA once daily, with or without food. Swallow CYMBALTA whole; do not crush or chew, do not open capsule. Take a missed dose as soon as it is remembered. Do not take two doses of CYMBALTA at the same time ( 2)

Indication Starting Dose Target Dose Maximum Dose MDD ( 2.1) 40 mg/day to 60 mg/day Acute Treatment: 40 mg/day (20 mg twice daily) to 60 mg/day (once daily or as 30 mg twice daily); Maintenance Treatment: 60 mg/day 120 mg/day GAD ( 2.2) Adults 60 mg/day 60 mg/day (once daily) 120 mg/day Elderly 30 mg/day 60 mg/day (once daily) 120 mg/day Children and Adolescents (7 to 17 years of age) 30 mg/day 30 to 60 mg/day (once daily) 120 mg/day DPNP ( 2.3) 60 mg/day 60 mg/day (once daily) 60 mg/day FM ( 2.4) 30 mg/day 60 mg/day (once daily) 60 mg/day Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain ( 2.5) 30 mg/day 60 mg/day (once daily) 60 mg/day - Some patients may benefit from starting at 30 mg once daily ( 2)

- There is no evidence that doses greater than 60 mg/day confers additional benefit, while some adverse reactions were observed to be dose-dependent ( 2)

- Discontinuing CYMBALTA: Gradually reduce dosage to avoid discontinuation symptoms ( 2.7, 5.7)

- Hepatic Impairment: Avoid use in patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis ( 5.14)

- Renal Impairment: Avoid use in patients with severe renal impairment, GFR <30 mL/min ( 5.14)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

20 mg, 30 mg, and 60 mg delayed-release capsules ( 3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Serotonin Syndrome and MAOIs: Do not use MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders with CYMBALTA or within 5 days of stopping treatment with CYMBALTA. Do not use CYMBALTA within 14 days of stopping an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders. In addition, do not start CYMBALTA in a patient who is being treated with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue ( 4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Hepatotoxicity: Hepatic failure, sometimes fatal, has been reported in patients treated with CYMBALTA. CYMBALTA should be discontinued in patients who develop jaundice or other evidence of clinically significant liver dysfunction and should not be resumed unless another cause can be established. CYMBALTA should not be prescribed to patients with substantial alcohol use or evidence of chronic liver disease ( 5.2)

- Orthostatic Hypotension, Falls and Syncope: Cases have been reported with CYMBALTA therapy ( 5.3)

- Serotonin Syndrome: Increased risk when co-administered with other serotonergic agents (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, triptans), but also when taken alone. If it occurs, discontinue CYMBALTA and initiate supportive treatment ( 5.4)

- Increased Risk of Bleeding: CYMBALTA may increase the risk of bleeding events. Concomitant use of NSAIDs, aspirin, other antiplatelet drugs, warfarin, and anticoagulants may increase this risk ( 5.5, 7.4, 8.1)

- Severe Skin Reactions: Severe skin reactions, including erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), can occur with CYMBALTA. CYMBALTA should be discontinued at the first appearance of blisters, peeling rash, mucosal erosions, or any other sign of hypersensitivity if no other etiology can be identified ( 5.6)

- Discontinuation: Taper dose when possible and monitor for discontinuation symptoms ( 5.7)

- Activation of mania or hypomania has occurred ( 5.8)

- Angle-Closure Glaucoma: Angle-closure glaucoma has occurred in patients with untreated anatomically narrow angles treated with antidepressants ( 5.9)

- Seizures: Prescribe with care in patients with a history of seizure disorder ( 5.10)

- Blood Pressure: Monitor blood pressure prior to initiating treatment and periodically throughout treatment ( 5.11)

- Inhibitors of CYP1A2 or Thioridazine: Should not administer with CYMBALTA ( 5.12)

- Hyponatremia: Can occur in association with SIADH. Cases of hyponatremia have been reported ( 5.13)

- Glucose Control in Diabetes: In diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain patients, small increases in fasting blood glucose, and HbA 1c have been observed ( 5.14)

- Conditions that Slow Gastric Emptying: Use cautiously in these patients ( 5.14)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

- Most common adverse reactions (≥5% and at least twice the incidence of placebo patients): nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis ( 6.3)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Eli Lilly and Company at 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

- Pregnancy: Third trimester use may increase risk for symptoms of poor adaptation (respiratory distress, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, hypotonia, tremor, irritability) in the neonate ( 8.1)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 11/2019

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Dosage for Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

2.2 Dosage for Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder

2.3 Dosage for Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain

2.4 Dosage for Treatment of Fibromyalgia

2.5 Dosage for Treatment of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

2.6 Dosing in Special Populations

2.7 Discontinuing CYMBALTA

2.8 Switching a Patient to or from a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) Intended to Treat Psychiatric Disorders

2.9 Use of CYMBALTA with Other MAOIs such as Linezolid or Methylene Blue

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

5.2 Hepatotoxicity

5.3 Orthostatic Hypotension, Falls and Syncope

5.4 Serotonin Syndrome

5.5 Increased Risk of Bleeding

5.6 Severe Skin Reactions

5.7 Discontinuation of Treatment with CYMBALTA

5.8 Activation of Mania/Hypomania

5.9 Angle-Closure Glaucoma

5.10 Seizures

5.11 Effect on Blood Pressure

5.12 Clinically Important Drug Interactions

5.13 Hyponatremia

5.14 Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness

5.15 Urinary Hesitation and Retention

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Studies Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Inhibitors of CYP1A2

7.2 Inhibitors of CYP2D6

7.3 Dual Inhibition of CYP1A2 and CYP2D6

7.4 Drugs that Interfere with Hemostasis (e.g., NSAIDs, Aspirin, and Warfarin)

7.5 Lorazepam

7.6 Temazepam

7.7 Drugs that Affect Gastric Acidity

7.8 Drugs Metabolized by CYP1A2

7.9 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6

7.10 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2C9

7.11 Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A

7.12 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2C19

7.13 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

7.14 Serotonergic Drugs

7.15 Alcohol

7.16 CNS Drugs

7.17 Drugs Highly Bound to Plasma Protein

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Gender

8.7 Smoking Status

8.8 Race

8.9 Hepatic Impairment

8.10 Severe Renal Impairment

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Signs and Symptoms

10.2 Management of Overdose

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Major Depressive Disorder

14.2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

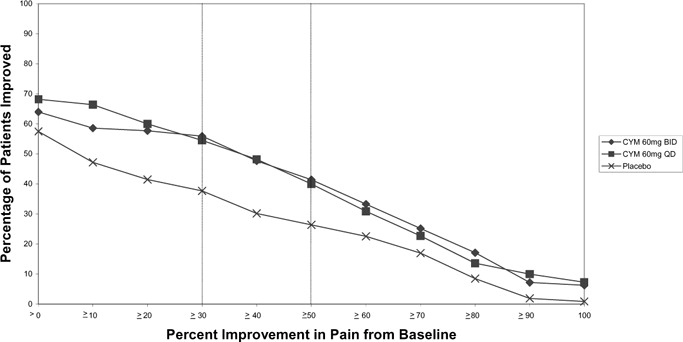

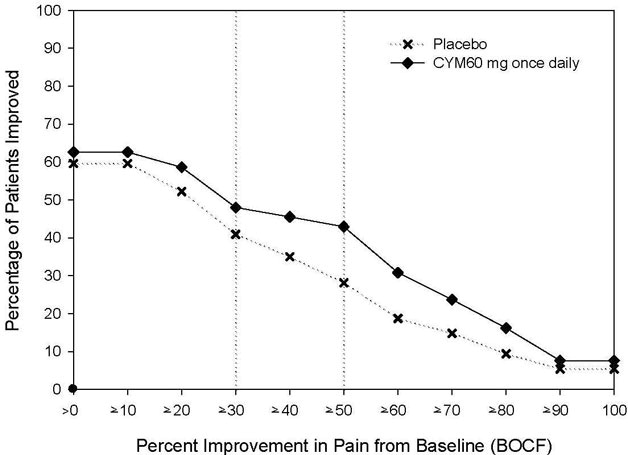

14.3 Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain

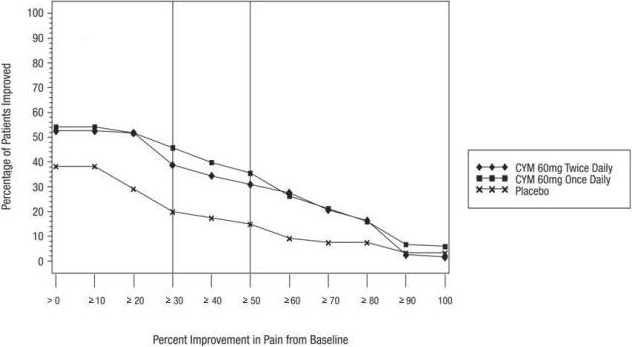

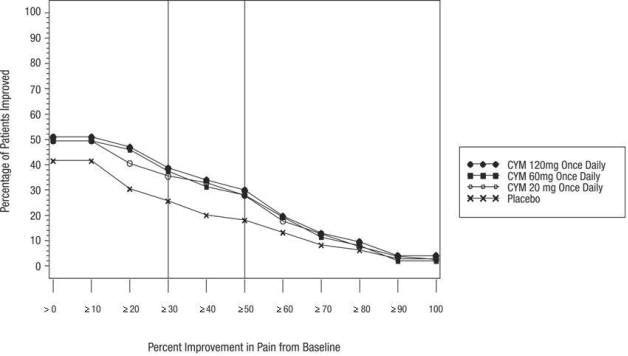

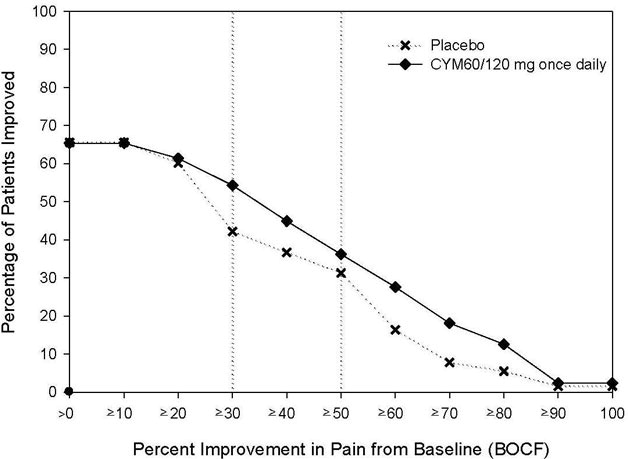

14.4 Fibromyalgia

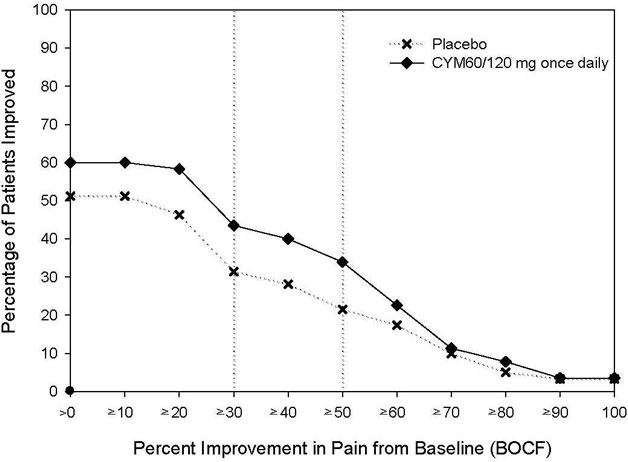

14.5 Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

16.1 How Supplied

16.2 Storage and Handling

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies. These studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant use in patients over age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressant use in patients aged 65 and older [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.1)] .

In patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy, monitor closely for worsening, and for emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Advise families and caregivers of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.1)] .

- 1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Swallow CYMBALTA whole. Do not chew or crush. Do not open the capsule and sprinkle its contents on food or mix with liquids. All of these might affect the enteric coating. CYMBALTA can be given without regard to meals. If a dose of CYMBALTA is missed, take the missed dose as soon as it is remembered. If it is almost time for the next dose, skip the missed dose and take the next dose at the regular time. Do not take two doses of CYMBALTA at the same time.

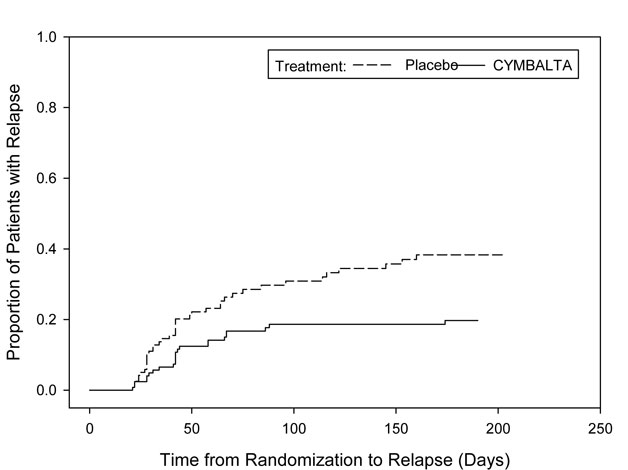

2.1 Dosage for Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

Administer CYMBALTA at a total dose of 40 mg/day (given as 20 mg twice daily) to 60 mg/day (given either once daily or as 30 mg twice daily). For some patients, it may be desirable to start at 30 mg once daily for 1 week, to allow patients to adjust to the medication before increasing to 60 mg once daily. While a 120 mg/day dose was shown to be effective, there is no evidence that doses greater than 60 mg/day confer any additional benefits. The safety of doses above 120 mg/day has not been adequately evaluated. Periodically reassess to determine the need for maintenance treatment and the appropriate dose for such treatment [see Clinical Studies ( 14.1)] .

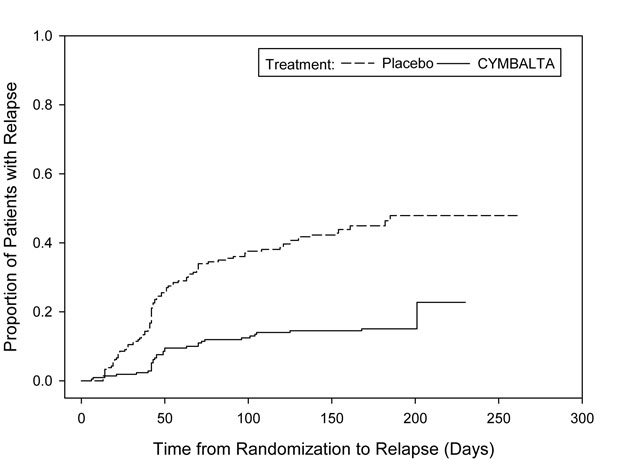

2.2 Dosage for Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Adults — For most patients, initiate CYMBALTA 60 mg once daily. For some patients, it may be desirable to start at 30 mg once daily for 1 week, to allow patients to adjust to the medication before increasing to 60 mg once daily. While a 120 mg once daily dose was shown to be effective, there is no evidence that doses greater than 60 mg/day confer additional benefit. Nevertheless, if a decision is made to increase the dose beyond 60 mg once daily, increase dose in increments of 30 mg once daily. The safety of doses above 120 mg once daily has not been adequately evaluated. Periodically reassess to determine the continued need for maintenance treatment and the appropriate dose for such treatment [see Clinical Studies ( 14.2)] .

Elderly — Initiate CYMBALTA at a dose of 30 mg once daily for 2 weeks before considering an increase to the target dose of 60 mg. Thereafter, patients may benefit from doses above 60 mg once daily. If a decision is made to increase the dose beyond 60 mg once daily, increase dose in increments of 30 mg once daily. The maximum dose studied was 120 mg per day. Safety of doses above 120 mg once daily has not been adequately evaluated [see Clinical Studies ( 14.2)] .

Children and Adolescents (7 to 17 years of age) — Initiate CYMBALTA at a dose of 30 mg once daily for 2 weeks before considering an increase to 60 mg. The recommended dose range is 30 to 60 mg once daily. Some patients may benefit from doses above 60 mg once daily. If a decision is made to increase the dose beyond 60 mg once daily, increase dose in increments of 30 mg once daily. The maximum dose studied was 120 mg per day. The safety of doses above 120 mg once daily has not been evaluated [see Clinical Studies ( 14.2)] .

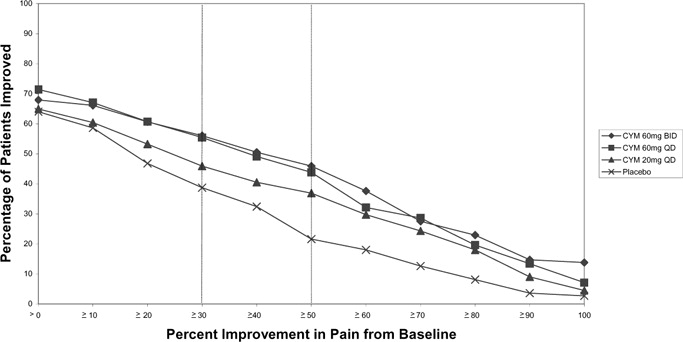

2.3 Dosage for Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain

Administer CYMBALTA 60 mg once daily. There is no evidence that doses higher than 60 mg confer additional significant benefit and the higher dose is clearly less well tolerated [see Clinical Studies ( 14.3)] . For patients for whom tolerability is a concern, a lower starting dose may be considered.

Since diabetes is frequently complicated by renal disease, consider a lower starting dose and gradual increase in dose for patients with renal impairment [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.6), Use in Specific Populations ( 8.10), and Clinical Pharmacology ( 12.3)] .

2.4 Dosage for Treatment of Fibromyalgia

Administer CYMBALTA 60 mg once daily. Begin treatment at 30 mg once daily for 1 week, to allow patients to adjust to the medication before increasing to 60 mg once daily. Some patients may respond to the starting dose. There is no evidence that doses greater than 60 mg/day confer additional benefit, even in patients who do not respond to a 60 mg dose, and higher doses are associated with a higher rate of adverse reactions [see Clinical Studies ( 14.4)] .

2.5 Dosage for Treatment of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

Administer CYMBALTA 60 mg once daily. Begin treatment at 30 mg for one week, to allow patients to adjust to the medication before increasing to 60 mg once daily. There is no evidence that higher doses confer additional benefit, even in patients who do not respond to a 60 mg dose, and higher doses are associated with a higher rate of adverse reactions [see Clinical Studies ( 14.5)] .

2.6 Dosing in Special Populations

2.7 Discontinuing CYMBALTA

Adverse reactions after discontinuation of CYMBALTA, after abrupt or tapered discontinuation, include: dizziness, headache, nausea, diarrhea, paresthesia, irritability, vomiting, insomnia, anxiety, hyperhidrosis, and fatigue. A gradual reduction in dosage rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.7)] .

2.8 Switching a Patient to or from a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) Intended to Treat Psychiatric Disorders

At least 14 days should elapse between discontinuation of an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders and initiation of therapy with CYMBALTA. Conversely, at least 5 days should be allowed after stopping CYMBALTA before starting an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders [see Contraindications ( 4)].

2.9 Use of CYMBALTA with Other MAOIs such as Linezolid or Methylene Blue

Do not start CYMBALTA in a patient who is being treated with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue because there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. In a patient who requires more urgent treatment of a psychiatric condition, other interventions, including hospitalization, should be considered [see Contraindications ( 4)].

In some cases, a patient already receiving CYMBALTA therapy may require urgent treatment with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. If acceptable alternatives to linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are not available and the potential benefits of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are judged to outweigh the risks of serotonin syndrome in a particular patient, CYMBALTA should be stopped promptly, and linezolid or intravenous methylene blue can be administered. The patient should be monitored for symptoms of serotonin syndrome for 5 days or until 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue, whichever comes first. Therapy with CYMBALTA may be resumed 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

The risk of administering methylene blue by non-intravenous routes (such as oral tablets or by local injection) or in intravenous doses much lower than 1 mg/kg with CYMBALTA is unclear. The clinician should, nevertheless, be aware of the possibility of emergent symptoms of serotonin syndrome with such use [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) — The use of MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders with CYMBALTA or within 5 days of stopping treatment with CYMBALTA is contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. The use of CYMBALTA within 14 days of stopping an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders is also contraindicated [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.8) and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

Starting CYMBALTA in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue is also contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.9) and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long-standing concern, however, that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment.

Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and others) showed that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18-24) with major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short-term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4400 patients. The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short-term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger patients for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk of differences (drug vs placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1000 patients treated) are provided in Table 1.

Table 1 Age Range Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1000 Patients Treated Increases Compared to Placebo <18 14 additional cases 18-24 5 additional cases Decreases Compared to Placebo 25-64 1 fewer case ≥65 6 fewer cases No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient's presenting symptoms.

If the decision has been made to discontinue treatment, medication should be tapered, as rapidly as is feasible, but with recognition that discontinuation can be associated with certain symptoms [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.7) and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.7) for descriptions of the risks of discontinuation of CYMBALTA] .

Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder or other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to health care providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers. Prescriptions for CYMBALTA should be written for the smallest quantity of capsules consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

Screening Patients for Bipolar Disorder — A major depressive episode may be the initial presentation of bipolar disorder. It is generally believed (though not established in controlled trials) that treating such an episode with an antidepressant alone may increase the likelihood of precipitation of a mixed/manic episode in patients at risk for bipolar disorder. Whether any of the symptoms described above represent such a conversion is unknown. However, prior to initiating treatment with an antidepressant, patients with depressive symptoms should be adequately screened to determine if they are at risk for bipolar disorder; such screening should include a detailed psychiatric history, including a family history of suicide, bipolar disorder, and depression. It should be noted that CYMBALTA is not approved for use in treating bipolar depression.

5.2 Hepatotoxicity

There have been reports of hepatic failure, sometimes fatal, in patients treated with CYMBALTA. These cases have presented as hepatitis with abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and elevation of transaminase levels to more than twenty times the upper limit of normal with or without jaundice, reflecting a mixed or hepatocellular pattern of liver injury. CYMBALTA should be discontinued in patients who develop jaundice or other evidence of clinically significant liver dysfunction and should not be resumed unless another cause can be established.

Cases of cholestatic jaundice with minimal elevation of transaminase levels have also been reported. Other postmarketing reports indicate that elevated transaminases, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase have occurred in patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.

CYMBALTA increased the risk of elevation of serum transaminase levels in development program clinical trials. Liver transaminase elevations resulted in the discontinuation of 0.3% (92/34,756) of CYMBALTA-treated patients. In most patients, the median time to detection of the transaminase elevation was about two months. In adult placebo-controlled trials in any indication, for patients with normal and abnormal baseline ALT values, elevation of ALT >3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 1.25% (144/11,496) of CYMBALTA-treated patients compared to 0.45% (39/8716) of placebo-treated patients. In adult placebo-controlled studies using a fixed dose design, there was evidence of a dose response relationship for ALT and AST elevation of >3 times the upper limit of normal and >5 times the upper limit of normal, respectively.

Because it is possible that CYMBALTA and alcohol may interact to cause liver injury or that CYMBALTA may aggravate pre-existing liver disease, CYMBALTA should not be prescribed to patients with substantial alcohol use or evidence of chronic liver disease.

5.3 Orthostatic Hypotension, Falls and Syncope

Orthostatic hypotension, falls and syncope have been reported with therapeutic doses of CYMBALTA. Syncope and orthostatic hypotension tend to occur within the first week of therapy but can occur at any time during CYMBALTA treatment, particularly after dose increases. The risk of falling appears to be related to the degree of orthostatic decrease in blood pressure as well as other factors that may increase the underlying risk of falls.

In an analysis of patients from all placebo-controlled trials, patients treated with CYMBALTA reported a higher rate of falls compared to patients treated with placebo. Risk appears to be related to the presence of orthostatic decrease in blood pressure. The risk of blood pressure decreases may be greater in patients taking concomitant medications that induce orthostatic hypotension (such as antihypertensives) or are potent CYP1A2 inhibitors [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12) and Drug Interactions ( 7.1)] and in patients taking CYMBALTA at doses above 60 mg daily. Consideration should be given to dose reduction or discontinuation of CYMBALTA in patients who experience symptomatic orthostatic hypotension, falls and/or syncope during CYMBALTA therapy.

Risk of falling also appeared to be proportional to a patient's underlying risk for falls and appeared to increase steadily with age. As elderly patients tend to have a higher underlying risk for falls due to a higher prevalence of risk factors such as use of multiple medications, medical comorbidities and gait disturbances, the impact of increasing age by itself is unclear. Falls with serious consequences including bone fractures and hospitalizations have been reported [see Adverse Reactions ( 6.10) and Patient Counseling Information ( 17)] .

5.4 Serotonin Syndrome

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome has been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs, including CYMBALTA, alone but particularly with concomitant use of other serotonergic drugs (including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, amphetamines, and St. John's Wort) and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin (in particular, MAOIs, both those intended to treat psychiatric disorders and also others, such as linezolid and intravenous methylene blue).

Serotonin syndrome symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, delirium, and coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, dizziness, diaphoresis, flushing, hyperthermia), neuromuscular symptoms (e.g., tremor, rigidity, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, incoordination), seizures, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Patients should be monitored for the emergence of serotonin syndrome.

The concomitant use of CYMBALTA with MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders is contraindicated. CYMBALTA should also not be started in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. All reports with methylene blue that provided information on the route of administration involved intravenous administration in the dose range of 1 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg. No reports involved the administration of methylene blue by other routes (such as oral tablets or local tissue injection) or at lower doses. There may be circumstances when it is necessary to initiate treatment with an MAOI such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue in a patient taking CYMBALTA. CYMBALTA should be discontinued before initiating treatment with the MAOI [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.8, 2.9), and Contraindications ( 4)].

If concomitant use of CYMBALTA with other serotonergic drugs including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, buspirone, tryptophan, amphetamines, and St. John's Wort is clinically warranted, patients should be made aware of a potential increased risk for serotonin syndrome, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases. Treatment with CYMBALTA and any concomitant serotonergic agents, should be discontinued immediately if the above events occur and supportive symptomatic treatment should be initiated.

5.5 Increased Risk of Bleeding

Drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake inhibition, including CYMBALTA, may increase the risk of bleeding events. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. A post-marketing study showed a higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in mothers taking duloxetine. Other bleeding events related to SSRI and SNRI use have ranged from ecchymoses, hematomas, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages. Concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may add to this risk. Drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake inhibition, including CYMBALTA, may increase the risk of bleeding events. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. A post-marketing study showed a higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in mothers taking duloxetine. Other bleeding events related to SSRI and SNRI use have ranged from ecchymoses, hematomas, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages. Concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may add to this risk.

Inform patients about the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of CYMBALTA and NSAIDs, aspirin, or other drugs that affect coagulation . Inform patients about the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of CYMBALTA and NSAIDs, aspirin, or other drugs that affect coagulation [see Drug Interactions ( 7.4)] .

5.6 Severe Skin Reactions

Severe skin reactions, including erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), can occur with CYMBALTA. The reporting rate of SJS associated with CYMBALTA use exceeds the general population background incidence rate for this serious skin reaction (1 to 2 cases per million person years). The reporting rate is generally accepted to be an underestimate due to underreporting.

CYMBALTA should be discontinued at the first appearance of blisters, peeling rash, mucosal erosions, or any other sign of hypersensitivity if no other etiology can be identified.

5.7 Discontinuation of Treatment with CYMBALTA

Discontinuation symptoms have been systematically evaluated in patients taking CYMBALTA. Following abrupt or tapered discontinuation in adult placebo-controlled clinical trials, the following symptoms occurred at 1% or greater and at a significantly higher rate in CYMBALTA-treated patients compared to those discontinuing from placebo: dizziness, headache, nausea, diarrhea, paresthesia, irritability, vomiting, insomnia, anxiety, hyperhidrosis, and fatigue.

During marketing of other SSRIs and SNRIs (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), there have been spontaneous reports of adverse events occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, hypomania, tinnitus, and seizures. Although these events are generally self-limiting, some have been reported to be severe.

Patients should be monitored for these symptoms when discontinuing treatment with CYMBALTA. A gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.7)] .

5.8 Activation of Mania/Hypomania

In adult placebo-controlled trials in patients with major depressive disorder, activation of mania or hypomania was reported in 0.1% (4/3779) of CYMBALTA-treated patients and 0.04% (1/2536) of placebo-treated patients. No activation of mania or hypomania was reported in DPNP, GAD, fibromyalgia, or chronic musculoskeletal pain placebo-controlled trials. Activation of mania or hypomania has been reported in a small proportion of patients with mood disorders who were treated with other marketed drugs effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder. As with these other agents, CYMBALTA should be used cautiously in patients with a history of mania.

5.9 Angle-Closure Glaucoma

The pupillary dilation that occurs following use of many antidepressant drugs including CYMBALTA may trigger an angle closure attack in a patient with anatomically narrow angles who does not have a patent iridectomy.

5.10 Seizures

CYMBALTA has not been systematically evaluated in patients with a seizure disorder, and such patients were excluded from clinical studies. In adult placebo-controlled clinical trials, seizures/convulsions occurred in 0.02% (3/12,722) of patients treated with CYMBALTA and 0.01% (1/9513) of patients treated with placebo. CYMBALTA should be prescribed with care in patients with a history of a seizure disorder.

5.11 Effect on Blood Pressure

In adult placebo-controlled clinical trials across indications from baseline to endpoint, CYMBALTA treatment was associated with mean increases of 0.5 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure and 0.8 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure compared to mean decreases of 0.6 mm Hg systolic and 0.3 mm Hg diastolic in placebo-treated patients. There was no significant difference in the frequency of sustained (3 consecutive visits) elevated blood pressure. In a clinical pharmacology study designed to evaluate the effects of CYMBALTA on various parameters, including blood pressure at supratherapeutic doses with an accelerated dose titration, there was evidence of increases in supine blood pressure at doses up to 200 mg twice daily. At the highest 200 mg twice daily dose, the increase in mean pulse rate was 5.0 to 6.8 beats and increases in mean blood pressure were 4.7 to 6.8 mm Hg (systolic) and 4.5 to 7 mm Hg (diastolic) up to 12 hours after dosing.

Blood pressure should be measured prior to initiating treatment and periodically measured throughout treatment [see Adverse Reactions ( 6.7)] .

5.12 Clinically Important Drug Interactions

Both CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 are responsible for CYMBALTA metabolism.

CYP1A2 Inhibitors — Co-administration of CYMBALTA with potent CYP1A2 inhibitors should be avoided [see Drug Interactions ( 7.1)] .

CYP2D6 Inhibitors — Because CYP2D6 is involved in CYMBALTA metabolism, concomitant use of CYMBALTA with potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 would be expected to, and does, result in higher concentrations (on average of 60%) of CYMBALTA [see Drug Interactions ( 7.2)] .

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6 — Co-administration of CYMBALTA with drugs that are extensively metabolized by CYP2D6 and that have a narrow therapeutic index, including certain antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], such as nortriptyline, amitriptyline, and imipramine), phenothiazines and Type 1C antiarrhythmics (e.g., propafenone, flecainide), should be approached with caution. Plasma TCA concentrations may need to be monitored and the dose of the TCA may need to be reduced if a TCA is co-administered with CYMBALTA. Because of the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death potentially associated with elevated plasma levels of thioridazine, CYMBALTA and thioridazine should not be co-administered [see Drug Interactions ( 7.9)] .

Alcohol — Use of CYMBALTA concomitantly with heavy alcohol intake may be associated with severe liver injury. For this reason, CYMBALTA should not be prescribed for patients with substantial alcohol use [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) and Drug Interactions ( 7.15)] .

CNS Acting Drugs — Given the primary CNS effects of CYMBALTA, it should be used with caution when it is taken in combination with or substituted for other centrally acting drugs, including those with a similar mechanism of action [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12) and Drug Interactions ( 7.16)] .

5.13 Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia may occur as a result of treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs, including CYMBALTA. In many cases, this hyponatremia appears to be the result of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). Cases with serum sodium lower than 110 mmol/L have been reported and appeared to be reversible when CYMBALTA was discontinued. Elderly patients may be at greater risk of developing hyponatremia with SSRIs and SNRIs. Also, patients taking diuretics or who are otherwise volume depleted may be at greater risk [see Use in Specific Populations ( 8.5)] . Discontinuation of CYMBALTA should be considered in patients with symptomatic hyponatremia and appropriate medical intervention should be instituted.

Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia include headache, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, weakness, and unsteadiness, which may lead to falls. More severe and/or acute cases have been associated with hallucination, syncope, seizure, coma, respiratory arrest, and death.

5.14 Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness

Clinical experience with CYMBALTA in patients with concomitant systemic illnesses is limited. There is no information on the effect that alterations in gastric motility may have on the stability of CYMBALTA's enteric coating. In extremely acidic conditions, CYMBALTA, unprotected by the enteric coating, may undergo hydrolysis to form naphthol. Caution is advised in using CYMBALTA in patients with conditions that may slow gastric emptying (e.g., some diabetics).

CYMBALTA has not been systematically evaluated in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable coronary artery disease. Patients with these diagnoses were generally excluded from clinical studies during the product's premarketing testing.

Hepatic Impairment — Avoid use in patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.6), Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2), and Use in Specific Populations ( 8.9)] .

Severe Renal Impairment — Avoid use in patients with severe renal impairment, GFR <30 mL/min. Increased plasma concentration of CYMBALTA, and especially of its metabolites, occur in patients with end-stage renal disease (requiring dialysis) [see Dosage and Administration ( 2.6) and Use in Specific Populations ( 8.10)] .

Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetes — As observed in DPNP trials, CYMBALTA treatment worsens glycemic control in some patients with diabetes. In three clinical trials of CYMBALTA for the management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, the mean duration of diabetes was approximately 12 years, the mean baseline fasting blood glucose was 176 mg/dL, and the mean baseline hemoglobin A 1c (HbA 1c) was 7.8%. In the 12-week acute treatment phase of these studies, CYMBALTA was associated with a small increase in mean fasting blood glucose as compared to placebo. In the extension phase of these studies, which lasted up to 52 weeks, mean fasting blood glucose increased by 12 mg/dL in the CYMBALTA group and decreased by 11.5 mg/dL in the routine care group. HbA 1c increased by 0.5% in the CYMBALTA and by 0.2% in the routine care groups.

5.15 Urinary Hesitation and Retention

CYMBALTA is in a class of drugs known to affect urethral resistance. If symptoms of urinary hesitation develop during treatment with CYMBALTA, consideration should be given to the possibility that they might be drug-related.

In post marketing experience, cases of urinary retention have been observed. In some instances of urinary retention associated with CYMBALTA use, hospitalization and/or catheterization has been needed.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are described below and elsewhere in the labeling:

- Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.1)]

- Hepatotoxicity [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2)]

- Orthostatic Hypotension, Falls and Syncope [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.3)]

- Serotonin Syndrome [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)]

- Abnormal Bleeding [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.5)]

- Severe Skin Reactions [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.6)]

- Discontinuation of Treatment with CYMBALTA [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.7)]

- Activation of Mania/Hypomania [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.8)]

- Angle-Closure Glaucoma [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.9)]

- Seizures [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.10)]

- Effect on Blood Pressure [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.11)]

- Clinically Important Drug Interactions [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12)]

- Hyponatremia [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.13)]

- Urinary Hesitation and Retention [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.15)]

6.1 Clinical Studies Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

The stated frequencies of adverse reactions represent the proportion of individuals who experienced, at least once, a treatment-emergent adverse reaction of the type listed. A reaction was considered treatment-emergent if it occurred for the first time or worsened while receiving therapy following baseline evaluation. Reactions reported during the studies were not necessarily caused by the therapy, and the frequencies do not reflect investigator impression (assessment) of causality.

Adults — The data described below reflect exposure to CYMBALTA in placebo-controlled trials for MDD (N=3779), GAD (N=1018), OA (N=503), CLBP (N=600), DPNP (N=906), and FM (N=1294). The population studied was 17 to 89 years of age; 65.7%, 60.8%, 60.6%, 42.9%, and 94.4% female; and 81.8%, 72.6%, 85.3%, 74.0%, and 85.7% Caucasian for MDD, GAD, OA and CLBP, DPNP, and FM, respectively. Most patients received doses of a total of 60 to 120 mg per day [see Clinical Studies ( 14)] .The data below do not include results of the trial examining the efficacy of CYMBALTA in patients ≥ 65 years old for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder; however, the adverse reactions observed in this geriatric sample were generally similar to adverse reactions in the overall adult population.

Children and Adolescents — The data described below reflect exposure to CYMBALTA in pediatric, 10-week, placebo-controlled trials for MDD (N=341) and GAD (N=135). The population studied (N=476) was 7 to 17 years of age with 42.4% children age 7 to 11 years of age, 50.6% female, and 68.6% white. Patients received 30-120 mg per day during placebo-controlled acute treatment studies. Additional data come from the overall total of 822 pediatric patients (age 7 to 17 years of age) with 41.7% children age 7 to 11 years of age and 51.8% female exposed to CYMBALTA in MDD and GAD clinical trials up to 36-weeks in length, in which most patients received 30-120 mg per day.

Adverse Reactions Reported as Reasons for Discontinuation of Treatment in Adult Placebo-Controlled Trials

Major Depressive Disorder — Approximately 8.4% (319/3779) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in placebo-controlled trials for MDD discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 4.6% (117/2536) of the patients receiving placebo. Nausea (CYMBALTA 1.1%, placebo 0.4%) was the only common adverse reaction reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (i.e., discontinuation occurring in at least 1% of the CYMBALTA-treated patients and at a rate of at least twice that of placebo).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder — Approximately 13.7% (139/1018) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in placebo-controlled trials for GAD discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 5.0% (38/767) for placebo. Common adverse reactions reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (as defined above) included nausea (CYMBALTA 3.3%, placebo 0.4%), and dizziness (CYMBALTA 1.3%, placebo 0.4%).

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain — Approximately 12.9% (117/906) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in placebo-controlled trials for DPNP discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 5.1% (23/448) for placebo. Common adverse reactions reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (as defined above) included nausea (CYMBALTA 3.5%, placebo 0.7%), dizziness (CYMBALTA 1.2%, placebo 0.4%), and somnolence (CYMBALTA 1.1%, placebo 0.0%).

Fibromyalgia — Approximately 17.5% (227/1294) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in 3 to 6 month placebo-controlled trials for FM discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 10.1% (96/955) for placebo. Common adverse reactions reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (as defined above) included nausea (CYMBALTA 2.0%, placebo 0.5%), headache (CYMBALTA 1.2%, placebo 0.3%), somnolence (CYMBALTA 1.1%, placebo 0.0%), and fatigue (CYMBALTA 1.1%, placebo 0.1%).

Chronic Pain due to Osteoarthritis — Approximately 15.7% (79/503) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in 13-week, placebo-controlled trials for chronic pain due to OA discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 7.3% (37/508) for placebo. Common adverse reactions reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (as defined above) included nausea (CYMBALTA 2.2%, placebo 1.0%).

Chronic Low Back Pain — Approximately 16.5% (99/600) of the patients who received CYMBALTA in 13-week, placebo-controlled trials for CLBP discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 6.3% (28/441) for placebo. Common adverse reactions reported as a reason for discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (as defined above) included nausea (CYMBALTA 3.0%, placebo 0.7%), and somnolence (CYMBALTA 1.0%, placebo 0.0%).

Most Common Adult Adverse Reactions

Pooled Trials for all Approved Indications — The most commonly observed adverse reactions in CYMBALTA-treated patients (incidence of at least 5% and at least twice the incidence in placebo patients) were nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis.

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain — The most commonly observed adverse reactions in CYMBALTA-treated patients (as defined above) were nausea, somnolence, decreased appetite, constipation, hyperhidrosis, and dry mouth.

Fibromyalgia — The most commonly observed adverse reactions in CYMBALTA-treated patients (as defined above) were nausea, dry mouth, constipation, somnolence, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis, and agitation.

Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 5% or More Among CYMBALTA-Treated Patients in Adult Placebo-Controlled Trials

Table 2 gives the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse reactions in placebo-controlled trials for approved indications that occurred in 5% or more of patients treated with CYMBALTA and with an incidence greater than placebo.

Table 2: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions: Incidence of 5% or More and Greater than Placebo in Placebo-Controlled Trials of Approved Indications a a The inclusion of an event in the table is determined based on the percentages before rounding; however, the percentages displayed in the table are rounded to the nearest integer.

b Also includes asthenia.

c Events for which there was a significant dose-dependent relationship in fixed-dose studies, excluding three MDD studies which did not have a placebo lead-in period or dose titration.

d Also includes initial insomnia, middle insomnia, and early morning awakening.

e Also includes hypersomnia and sedation.

f Also includes abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain lower, abdominal pain upper, abdominal tenderness, and gastrointestinal pain.

Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction Adverse Reaction CYMBALTA

(N=8100)Placebo

(N=5655)Nausea c 23 8 Headache 14 12 Dry mouth 13 5 Somnolence e 10 3 Fatigue b,c 9 5 Insomnia d 9 5 Constipation c 9 4 Dizziness c 9 5 Diarrhea 9 6 Decreased appetite c 7 2 Hyperhidrosis c 6 1 Abdominal pain f 5 4 Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 2% or More Among CYMBALTA-Treated Patients in Adult Placebo-Controlled Trials

Pooled MDD and GAD Trials — Table 3 gives the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse reactions in MDD and GAD placebo-controlled trials for approved indications that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with CYMBALTA and with an incidence greater than placebo.

Table 3: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions: Incidence of 2% or More and Greater than Placebo in MDD and GAD Placebo-Controlled Trials a,b a The inclusion of an event in the table is determined based on the percentages before rounding; however, the percentages displayed in the table are rounded to the nearest integer.

b For GAD, there were no adverse events that were significantly different between treatments in adults ≥65 years that were also not significant in the adults <65 years.

c Events for which there was a significant dose-dependent relationship in fixed-dose studies, excluding three MDD studies which did not have a placebo lead-in period or dose titration.

d Also includes abdominal pain upper, abdominal pain lower, abdominal tenderness, abdominal discomfort, and gastrointestinal pain.

e Also includes asthenia.

f Also includes hypersomnia and sedation.

g Also includes initial insomnia, middle insomnia, and early morning awakening.

h Also includes feeling jittery, nervousness, restlessness, tension and psychomotor hyperactivity.

i Also includes loss of libido.

j Also includes anorgasmia.

Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction System Organ Class / Adverse Reaction CYMBALTA

(N=4797)Placebo

(N=3303)Cardiac Disorders Palpitations 2 1 Eye Disorders Vision blurred 3 1 Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea c 23 8 Dry mouth 14 6 Constipation c 9 4 Diarrhea 9 6 Abdominal pain d 5 4 Vomiting 4 2 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue e 9 5 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Decreased appetite c 6 2 Nervous System Disorders Headache 14 14 Dizziness c 9 5 Somnolence f 9 3 Tremor 3 1 Psychiatric Disorders Insomnia g 9 5 Agitation h 4 2 Anxiety 3 2 Reproductive System and Breast Disorders Erectile dysfunction 4 1 Ejaculation delayed c 2 1 Libido decreased i 3 1 Orgasm abnormal j 2 <1 Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders Yawning 2 <1 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Hyperhidrosis 6 2 DPNP, FM, OA, and CLBP — Table 4 gives the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with CYMBALTA (determined prior to rounding) in the premarketing acute phase of DPNP, FM, OA, and CLBP placebo-controlled trials and with an incidence greater than placebo.

Table 4: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions: Incidence of 2% or More and Greater than Placebo in DPNP, FM, OA, and CLBP Placebo-Controlled Trials a a The inclusion of an event in the table is determined based on the percentages before rounding; however, the percentages displayed in the table are rounded to the nearest integer.

b Incidence of 120 mg/day is significantly greater than the incidence for 60 mg/day.

c Also includes abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain lower, abdominal pain upper, abdominal tenderness and gastrointestinal pain.

d Also includes asthenia.

e Also includes myalgia and neck pain.

f Also includes hypersomnia and sedation.

g Also includes hypoaesthesia, hypoaesthesia facial, genital hypoaesthesia and paraesthesia oral.

h Also includes initial insomnia, middle insomnia, and early morning awakening.

i Also includes feeling jittery, nervousness, restlessness, tension and psychomotor hyperactivity.

j Also includes ejaculation failure.

k Also includes hot flush.

l Also includes blood pressure diastolic increased, blood pressure systolic increased, diastolic hypertension, essential hypertension, hypertension, hypertensive crisis, labile hypertension, orthostatic hypertension, secondary hypertension, and systolic hypertension.

Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction System Organ Class / Adverse Reaction CYMBALTA

(N=3303)Placebo

(N=2352)Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea 23 7 Dry Mouth b 11 3 Constipation b 10 3 Diarrhea 9 5 Abdominal Pain c 5 4 Vomiting 3 2 Dyspepsia 2 1 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue d 11 5 Infections and Infestations Nasopharyngitis 4 4 Upper Respiratory Tract Infection 3 3 Influenza 2 2 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Decreased Appetite b 8 1 Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain e 3 3 Muscle Spasms 2 2 Nervous System Disorders Headache 13 8 Somnolence b,f 11 3 Dizziness 9 5 Paraesthesia g 2 2 Tremor b 2 <1 Psychiatric Disorders Insomnia b,h 10 5 Agitation i 3 1 Reproductive System and Breast Disorders Erectile Dysfunction b 4 <1 Ejaculation Disorder j 2 <1 Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders Cough 2 2 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Hyperhidrosis 6 1 Vascular Disorders Flushing k 3 1 Blood pressure increased l 2 1 Effects on Male and Female Sexual Function in Adults

Changes in sexual desire, sexual performance and sexual satisfaction often occur as manifestations of psychiatric disorders or diabetes, but they may also be a consequence of pharmacologic treatment. Because adverse sexual reactions are presumed to be voluntarily underreported, the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX), a validated measure designed to identify sexual side effects, was used prospectively in 4 MDD placebo-controlled trials. In these trials, as shown in Table 5 below, patients treated with CYMBALTA experienced significantly more sexual dysfunction, as measured by the total score on the ASEX, than did patients treated with placebo. Gender analysis showed that this difference occurred only in males. Males treated with CYMBALTA experienced more difficulty with ability to reach orgasm (ASEX Item 4) than males treated with placebo. Females did not experience more sexual dysfunction on CYMBALTA than on placebo as measured by ASEX total score. Negative numbers signify an improvement from a baseline level of dysfunction, which is commonly seen in depressed patients. Physicians should routinely inquire about possible sexual side effects.

Table 5: Mean Change in ASEX Scores by Gender in MDD Placebo-Controlled Trials a n=Number of patients with non-missing change score for ASEX total.

b p=0.013 versus placebo.

c p<0.001 versus placebo.

Male Patientsa Female Patientsa CYMBALTA

(n=175)Placebo

(n=83)CYMBALTA

(n=241)Placebo

(n=126)ASEX Total (Items 1-5) 0.56 b -1.07 -1.15 -1.07 Item 1 — Sex drive -0.07 -0.12 -0.32 -0.24 Item 2 — Arousal 0.01 -0.26 -0.21 -0.18 Item 3 — Ability to achieve erection (men); Lubrication (women) 0.03 -0.25 -0.17 -0.18 Item 4 — Ease of reaching orgasm 0.40 c -0.24 -0.09 -0.13 Item 5 — Orgasm satisfaction 0.09 -0.13 -0.11 -0.17 Vital Sign Changes in Adults

In placebo-controlled clinical trials across approved indications for change from baseline to endpoint, CYMBALTA treatment was associated with mean increases of 0.23 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure and 0.73 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure compared to mean decreases of 1.09 mm Hg systolic and 0.55 mm Hg diastolic in placebo-treated patients. There was no significant difference in the frequency of sustained (3 consecutive visits) elevated blood pressure [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.3, 5.11)] .

CYMBALTA treatment, for up to 26 weeks in placebo-controlled trials across approved indications, typically caused a small increase in heart rate for change from baseline to endpoint compared to placebo of up to 1.37 beats per minute (increase of 1.20 beats per minute in CYMBALTA-treated patients, decrease of 0.17 beats per minute in placebo-treated patients).

Laboratory Changes in Adults

CYMBALTA treatment in placebo-controlled clinical trials across approved indications, was associated with small mean increases from baseline to endpoint in ALT, AST, CPK, and alkaline phosphatase; infrequent, modest, transient, abnormal values were observed for these analytes in CYMBALTA-treated patients when compared with placebo-treated patients [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2)] . High bicarbonate, cholesterol, and abnormal (high or low) potassium, were observed more frequently in CYMBALTA treated patients compared to placebo.

Electrocardiogram Changes in Adults

The effect of CYMBALTA 160 mg and 200 mg administered twice daily to steady state was evaluated in a randomized, double-blinded, two-way crossover study in 117 healthy female subjects. No QT interval prolongation was detected. CYMBALTA appears to be associated with concentration-dependent but not clinically meaningful QT shortening.

Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Premarketing and Postmarketing Clinical Trial Evaluation of CYMBALTA in Adults

Following is a list of treatment-emergent adverse reactions reported by patients treated with CYMBALTA in clinical trials. In clinical trials of all indications, 34,756 patients were treated with CYMBALTA. Of these, 26.9% (9337) took CYMBALTA for at least 6 months, and 12.4% (4317) for at least one year. The following listing is not intended to include reactions (1) already listed in previous tables or elsewhere in labeling, (2) for which a drug cause was remote, (3) which were so general as to be uninformative, (4) which were not considered to have significant clinical implications, or (5) which occurred at a rate equal to or less than placebo.

Reactions are categorized by body system according to the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare reactions are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Cardiac Disorders — Frequent: palpitations; Infrequent: myocardial infarction, tachycardia, and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Ear and Labyrinth Disorders — Frequent: vertigo; Infrequent: ear pain and tinnitus.

Endocrine Disorders — Infrequent: hypothyroidism.

Eye Disorders — Frequent: vision blurred; Infrequent: diplopia, dry eye, and visual impairment.

Gastrointestinal Disorders — Frequent: flatulence; Infrequent: dysphagia, eructation, gastritis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, halitosis, and stomatitis; Rare: gastric ulcer.

General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions — Frequent: chills/rigors; Infrequent: falls, feeling abnormal, feeling hot and/or cold, malaise, and thirst; Rare: gait disturbance.

Infections and Infestations — Infrequent: gastroenteritis and laryngitis.

Investigations — Frequent: weight increased, weight decreased; Infrequent: blood cholesterol increased.

Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders — Infrequent: dehydration and hyperlipidemia; Rare: dyslipidemia.

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders — Frequent: musculoskeletal pain; Infrequent: muscle tightness and muscle twitching.

Nervous System Disorders — Frequent: dysgeusia, lethargy, and paraesthesia/hypoesthesia; Infrequent: disturbance in attention, dyskinesia, myoclonus, and poor quality sleep; Rare: dysarthria.

Psychiatric Disorders — Frequent: abnormal dreams and sleep disorder; Infrequent: apathy, bruxism, disorientation/confusional state, irritability, mood swings, and suicide attempt; Rare: completed suicide.

Renal and Urinary Disorders — Frequent: urinary frequency; Infrequent: dysuria, micturition urgency, nocturia, polyuria, and urine odor abnormal.

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders — Frequent: anorgasmia/orgasm abnormal; Infrequent: menopausal symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and testicular pain; Rare: menstrual disorder.

Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders — Frequent: yawning, oropharyngeal pain; Infrequent: throat tightness.

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders — Frequent: pruritus; Infrequent: cold sweat, dermatitis contact, erythema, increased tendency to bruise, night sweats, and photosensitivity reaction; Rare: ecchymosis.

Vascular Disorders — Frequent: hot flush; Infrequent: flushing, orthostatic hypotension, and peripheral coldness.

Adverse Reactions Observed in Children and Adolescent Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials

The adverse drug reaction profile observed in pediatric clinical trials (children and adolescents) was consistent with the adverse drug reaction profile observed in adult clinical trials. The specific adverse drug reactions observed in adult patients can be expected to be observed in pediatric patients (children and adolescents) [see Adverse Reactions ( 6.5)] . The most common (≥5% and twice placebo) adverse reactions observed in pediatric clinical trials include: nausea, diarrhea, decreased weight, and dizziness.

Table 6 provides the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse reactions in MDD and GAD pediatric placebo-controlled trials that occurred in greater than 2% of patients treated with CYMBALTA and with an incidence greater than placebo.

Table 6: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions: Incidence of 2% or More and Greater than Placebo in three 10-week Pediatric Placebo-Controlled Trials a a The inclusion of an event in the table is determined based on the percentages before rounding; however, the percentages displayed in the table are rounded to the nearest integer.

b Also includes abdominal pain upper, abdominal pain lower, abdominal tenderness, abdominal discomfort, and gastrointestinal pain.

c Also includes asthenia.

d Frequency based on weight measurement meeting potentially clinically significant threshold of ≥3.5% weight loss (N=467 CYMBALTA; N=354 Placebo).

e Also includes hypersomnia and sedation.

f Also includes initial insomnia, insomnia, middle insomnia, and terminal insomnia.

Percentage of Pediatric Patients Reporting Reaction System Organ Class/Adverse Reaction CYMBALTA

(N=476)Placebo

(N=362)Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea 18 8 Abdominal Pain b 13 10 Vomiting 9 4 Diarrhea 6 3 Dry Mouth 2 1 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue c 7 5 Investigations Decreased Weight d 14 6 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Decreased Appetite 10 5 Nervous System Disorders Headache 18 13 Somnolence e 11 6 Dizziness 8 4 Psychiatric Disorders Insomnia f 7 4 Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders Oropharyngeal Pain 4 2 Cough 3 1 Other adverse reactions that occurred at an incidence of less than 2% but were reported by more CYMBALTA treated patients than placebo treated patients and are associated CYMBALTA treatment: abnormal dreams (including nightmare), anxiety, flushing (including hot flush), hyperhidrosis, palpitations, pulse increased, and tremor.

Discontinuation-emergent symptoms have been reported when stopping CYMBALTA. The most commonly reported symptoms following discontinuation of CYMBALTA in pediatric clinical trials have included headache, dizziness, insomnia, and abdominal pain [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.7) and Adverse Reactions ( 6.2)] .

Growth (Height and Weight) — Decreased appetite and weight loss have been observed in association with the use of SSRIs and SNRIs. Pediatric patients treated with CYMBALTA in clinical trials experienced a 0.1 kg mean decrease in weight at 10 weeks, compared with a mean weight gain of approximately 0.9 kg in placebo-treated patients. The proportion of patients who experienced a clinically significant decrease in weight (≥3.5%) was greater in the CYMBALTA group than in the placebo group (14% and 6%, respectively). Subsequently, over the 4- to 6-month uncontrolled extension periods, CYMBALTA-treated patients on average trended toward recovery to their expected baseline weight percentile based on population data from age- and sex-matched peers. In studies up to 9 months, CYMBALTA-treated pediatric patients experienced an increase in height of 1.7 cm on average (2.2 cm increase in children [7 to 11 years of age] and 1.3 cm increase in adolescents [12 to 17 years of age]). While height increase was observed during these studies, a mean decrease of 1% in height percentile was observed (decrease of 2% in children [7 to 11 years of age] and increase of 0.3% in adolescents [12 to 17 years of age]). Weight and height should be monitored regularly in children and adolescents treated with CYMBALTA.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post approval use of CYMBALTA. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Adverse reactions reported since market introduction that were temporally related to CYMBALTA therapy and not mentioned elsewhere in labeling include: acute pancreatitis, anaphylactic reaction, aggression and anger (particularly early in treatment or after treatment discontinuation), angioneurotic edema, angle-closure glaucoma, colitis (microscopic or unspecified), cutaneous vasculitis (sometimes associated with systemic involvement), extrapyramidal disorder, galactorrhea, gynecological bleeding, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperprolactinemia, hypersensitivity, hypertensive crisis, muscle spasm, rash, restless legs syndrome, seizures upon treatment discontinuation, supraventricular arrhythmia, tinnitus (upon treatment discontinuation), trismus, and urticaria.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

Both CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 are responsible for duloxetine metabolism.

7.1 Inhibitors of CYP1A2

When duloxetine 60 mg was co-administered with fluvoxamine 100 mg, a potent CYP1A2 inhibitor, to male subjects (n=14) duloxetine AUC was increased approximately 6-fold, the C max was increased about 2.5-fold, and duloxetine t 1/2 was increased approximately 3-fold. Other drugs that inhibit CYP1A2 metabolism include cimetidine and quinolone antimicrobials such as ciprofloxacin and enoxacin [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12)] .

7.2 Inhibitors of CYP2D6

Concomitant use of duloxetine (40 mg once daily) with paroxetine (20 mg once daily) increased the concentration of duloxetine AUC by about 60%, and greater degrees of inhibition are expected with higher doses of paroxetine. Similar effects would be expected with other potent CYP2D6 inhibitors (e.g., fluoxetine, quinidine) [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12)] .

7.3 Dual Inhibition of CYP1A2 and CYP2D6

Concomitant administration of duloxetine 40 mg twice daily with fluvoxamine 100 mg, a potent CYP1A2 inhibitor, to CYP2D6 poor metabolizer subjects (n=14) resulted in a 6-fold increase in duloxetine AUC and C max.

7.4 Drugs that Interfere with Hemostasis (e.g., NSAIDs, Aspirin, and Warfarin)

Serotonin release by platelets plays an important role in hemostasis. Epidemiological studies of the case-control and cohort design that have demonstrated an association between use of psychotropic drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding have also shown that concurrent use of an NSAID or aspirin may potentiate this risk of bleeding. Altered anticoagulant effects, including increased bleeding, have been reported when SSRIs or SNRIs are co-administered with warfarin. Concomitant administration of warfarin (2-9 mg once daily) under steady state conditions with duloxetine 60 or 120 mg once daily for up to 14 days in healthy subjects (n=15) did not significantly change INR from baseline (mean INR changes ranged from 0.05 to +0.07). The total warfarin (protein bound plus free drug) pharmacokinetics (AUC τ,ss, C max,ss or t max,ss) for both R- and S-warfarin were not altered by duloxetine. Because of the potential effect of duloxetine on platelets, patients receiving warfarin therapy should be carefully monitored when duloxetine is initiated or discontinued [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.5)] .

7.5 Lorazepam

Under steady-state conditions for duloxetine (60 mg Q 12 hours) and lorazepam (2 mg Q 12 hours), the pharmacokinetics of duloxetine were not affected by co-administration.

7.6 Temazepam

Under steady-state conditions for duloxetine (20 mg qhs) and temazepam (30 mg qhs), the pharmacokinetics of duloxetine were not affected by co-administration.

7.7 Drugs that Affect Gastric Acidity

CYMBALTA has an enteric coating that resists dissolution until reaching a segment of the gastrointestinal tract where the pH exceeds 5.5. In extremely acidic conditions, CYMBALTA, unprotected by the enteric coating, may undergo hydrolysis to form naphthol. Caution is advised in using CYMBALTA in patients with conditions that may slow gastric emptying (e.g., some diabetics). Drugs that raise the gastrointestinal pH may lead to an earlier release of duloxetine. However, co-administration of CYMBALTA with aluminum- and magnesium-containing antacids (51 mEq) or CYMBALTA with famotidine, had no significant effect on the rate or extent of duloxetine absorption after administration of a 40 mg oral dose. It is unknown whether the concomitant administration of proton pump inhibitors affects duloxetine absorption [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.14)] .

7.8 Drugs Metabolized by CYP1A2

In vitro drug interaction studies demonstrate that duloxetine does not induce CYP1A2 activity. Therefore, an increase in the metabolism of CYP1A2 substrates (e.g., theophylline, caffeine) resulting from induction is not anticipated, although clinical studies of induction have not been performed. Duloxetine is an inhibitor of the CYP1A2 isoform in in vitro studies, and in two clinical studies the average (90% confidence interval) increase in theophylline AUC was 7% (1%-15%) and 20% (13%-27%) when co-administered with duloxetine (60 mg twice daily).

7.9 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6

Duloxetine is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6. When duloxetine was administered (at a dose of 60 mg twice daily) in conjunction with a single 50 mg dose of desipramine, a CYP2D6 substrate, the AUC of desipramine increased 3-fold [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12)] .

7.10 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2C9

Results of in vitro studies demonstrate that duloxetine does not inhibit activity. In a clinical study, the pharmacokinetics of S-warfarin, a CYP2C9 substrate, were not significantly affected by duloxetine [see Drug Interactions ( 7.4)] .

7.11 Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A

Results of in vitro studies demonstrate that duloxetine does not inhibit or induce CYP3A activity. Therefore, an increase or decrease in the metabolism of CYP3A substrates (e.g., oral contraceptives and other steroidal agents) resulting from induction or inhibition is not anticipated, although clinical studies have not been performed.

7.12 Drugs Metabolized by CYP2C19

Results of in vitro studies demonstrate that duloxetine does not inhibit CYP2C19 activity at therapeutic concentrations. Inhibition of the metabolism of CYP2C19 substrates is therefore not anticipated, although clinical studies have not been performed.

7.13 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

[See Dosage and Administration ( 2.8, 2.9), Contraindications ( 4), and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

7.14 Serotonergic Drugs

[See Dosage and Administration ( 2.8, 2.9), Contraindications ( 4), and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.4)] .

7.15 Alcohol

When CYMBALTA and ethanol were administered several hours apart so that peak concentrations of each would coincide, CYMBALTA did not increase the impairment of mental and motor skills caused by alcohol.

In the CYMBALTA clinical trials database, three CYMBALTA-treated patients had liver injury as manifested by ALT and total bilirubin elevations, with evidence of obstruction. Substantial intercurrent ethanol use was present in each of these cases, and this may have contributed to the abnormalities seen [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2, 5.12)] .

7.17 Drugs Highly Bound to Plasma Protein

Because duloxetine is highly bound to plasma protein, administration of CYMBALTA to a patient taking another drug that is highly protein bound may cause increased free concentrations of the other drug, potentially resulting in adverse reactions. However, co-administration of duloxetine (60 or 120 mg) with warfarin (2-9 mg), a highly protein-bound drug, did not result in significant changes in INR and in the pharmacokinetics of either total S-or total R-warfarin (protein bound plus free drug) [see Drug Interactions ( 7.4)] .

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors the pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to CYMBALTA during pregnancy. To enroll, contact the CYMBALTA Pregnancy Registry at 1-866-814-6975 or www.cymbaltapregnancyregistry.com.

Risk Summary

Data from a postmarketing retrospective cohort study indicate that use of duloxetine in the month before delivery may be associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Data from published literature and from a postmarketing retrospective cohort study have not identified a clear drug-associated risk of major birth defects or other adverse developmental outcomes (see Data). There are risks associated with untreated depression and fibromyalgia in pregnancy, and with exposure to SNRIs and SSRIs, including CYMBALTA, during pregnancy (see Clinical Considerations).

In rats and rabbits treated with duloxetine during the period of organogenesis, fetal weights were decreased but there was no evidence of developmental effects at doses up to 3 and 6 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 120 mg/day given to adolescents on a mg/m 2 basis. When duloxetine was administered orally to pregnant rats throughout gestation and lactation, pup weights at birth and pup survival to 1 day postpartum were decreased at a dose 2 times the MRHD given to adolescents on a mg/m 2 basis. At this dose, pup behaviors consistent with increased reactivity, such as increased startle response to noise and decreased habituation of locomotor activity were observed. Post-weaning growth was not adversely affected.

The estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 to 4% and 15 to 20%, respectively.

Clinical Considerations

Disease-associated Maternal and/or Embryo/Fetal Risk

Women who discontinue antidepressants during pregnancy are more likely to experience a relapse of major depression than women who continue antidepressants. This finding is from a prospective, longitudinal study that followed 201 pregnant women with a history of major depressive disorder who were euthymic and taking antidepressants at the beginning of pregnancy. Consider the risk of untreated depression when discontinuing or changing treatment with antidepressant medication during pregnancy and postpartum.

Pregnant women with fibromyalgia are at increased risk for adverse maternal and infant outcomes including preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm birth, small for gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction, placental disruption, and venous thrombosis. It is not known if these adverse maternal and fetal outcomes are a direct result of fibromyalgia or other comorbid factors.

Maternal Adverse Reactions

Use of duloxetine in the month before delivery may be associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.5)] .

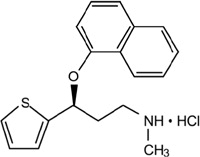

Fetal/Neonatal Adverse Reaction