Diazepam by Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. / DPT Laboratories, Ltd. DIAZEPAM gel

Diazepam by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Diazepam by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., DPT Laboratories, Ltd.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

Diazepam rectal gel rectal delivery system is a non-sterile diazepam gel provided in a prefilled, unit-dose, rectal delivery system. Diazepam rectal gel contains 5 mg/mL diazepam, propylene glycol, ethyl alcohol (10%), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, sodium benzoate, benzyl alcohol (1.5%), benzoic acid and water. Diazepam rectal gel is clear to slightly yellow and has a pH between 6.5 - 7.2.

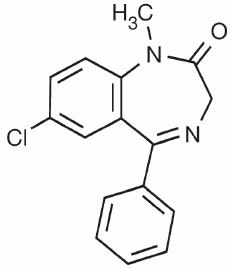

Diazepam, the active ingredient of diazepam rectal gel, is a benzodiazepine anticonvulsant with the chemical name 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one. The structural formula is as follows:

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

Although the precise mechanism by which diazepam exerts its antiseizure effects is unknown, animal and in vitro studies suggest that diazepam acts to suppress seizures through an interaction with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors of the A-type (GABAA). GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, acts at this receptor to open the membrane channel allowing chloride ions to flow into neurons. Entry of chloride ions causes an inhibitory potential that reduces the ability of neurons to depolarize to the threshold potential necessary to produce action potentials. Excessive depolarization of neurons is implicated in the generation and spread of seizures. It is believed that diazepam enhances the actions of GABA by causing GABA to bind more tightly to the GABAA receptor.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic information of diazepam following rectal administration was obtained from studies conducted in healthy adult subjects. No pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in pediatric patients. Therefore, information from the literature is used to define pharmacokinetic labeling in the pediatric population.

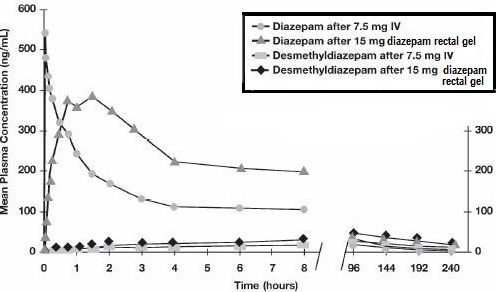

Diazepam rectal gel is well absorbed following rectal administration, reaching peak plasma concentrations in 1.5 hours. The absolute bioavailability of diazepam rectal gel relative to Valium® injectable is 90%. The volume of distribution of diazepam rectal gel is calculated to be approximately 1 L/kg. The mean elimination half-life of diazepam and desmethyldiazepam following administration of a 15 mg dose of diazepam rectal gel was found to be about 46 hours (CV=43%) and 71 hours (CV=37%), respectively.

Both diazepam and its major active metabolite desmethyldiazepam bind extensively to plasma proteins (95-98%).

FIGURE 1: Plasma Concentrations of Diazepam and Desmethyldiazepam Following Diazepam Rectal Gel or IV Diazepam

FIGURE 1: Plasma Concentrations of Diazepam and Desmethyldiazepam Following Diazepam Rectal Gel or IV Diazepam

Metabolism and Elimination: It has been reported in the literature that diazepam is extensively metabolized to one major active metabolite (desmethyldiazepam) and two minor active metabolites, 3-hydroxydiazepam (temazepam) and 3-hydroxy-N-diazepam (oxazepam) in plasma. At therapeutic doses, desmethyldiazepam is found in plasma at concentrations equivalent to those of diazepam while oxazepam and temazepam are not usually detectable. The metabolism of diazepam is primarily hepatic and involves demethylation (involving primarily CYP2C19 and CYP3A4) and 3-hydroxylation (involving primarily CYP3A4), followed by glucuronidation. The marked inter-individual variability in the clearance of diazepam reported in the literature is probably attributable to variability of CYP2C19 (which is known to exhibit genetic polymorphism; about 3-5% of Caucasians have little or no activity and are “poor metabolizers”) and CYP3A4. No inhibition was demonstrated in the presence of inhibitors selective for CYP2A6, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, or CYP1A2, indicating that these enzymes are not significantly involved in metabolism of diazepam.

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment: No pharmacokinetic studies were conducted with diazepam rectal gel in hepatically impaired subjects. Literature review indicates that following administration of 0.1 to 0.15 mg/kg of diazepam intravenously, the half-life of diazepam was prolonged by two to five-fold in subjects with alcoholic cirrhosis (n=24) compared to age-matched control subjects (n=37) with a corresponding decrease in clearance by half: however, the exact degree of hepatic impairment in these subjects was not characterized in this literature (see PRECAUTIONS section).

Renal Impairment: The pharmacokinetics of diazepam have not been studied in renally impaired subjects (see PRECAUTIONS section).

Pediatrics: No pharmacokinetic studies were conducted with diazepam rectal gel in the pediatric population. However, literature review indicates that following IV administration (0.33 mg/kg), diazepam has a longer half-life in neonates (birth up to one month; approximately 50-95 hours) and infants (one month up to two years; about 40-50 hours), whereas it has a shorter half-life in children (two to 12 years; approximately 15-21 hours) and adolescents (12 to 16 years; about 18-20 hours) (see PRECAUTIONS section).

Elderly: A study of single dose IV administration of diazepam (0.1 mg/kg) indicates that the elimination half-life of diazepam increases linearly with age, ranging from about 15 hours at 18 years (healthy young adults) to about 100 hours at 95 years (healthy elderly) with a corresponding decrease in clearance of free diazepam (see PRECAUTIONS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION sections).

Effect of Gender, Race, and Cigarette Smoking: No targeted pharmacokinetic studies have been conducted to evaluate the effect of gender, race, and cigarette smoking on the pharmacokinetics of diazepam. However, covariate analysis of a population of treated patients following administration of diazepam rectal gel, indicated that neither gender nor cigarette smoking had any effect on the pharmacokinetics of diazepam.

Clinical Studies

The effectiveness of diazepam rectal gel has been established in two adequate and well controlled clinical studies in children and adults exhibiting the seizure pattern described below under INDICATIONS AND USAGE.

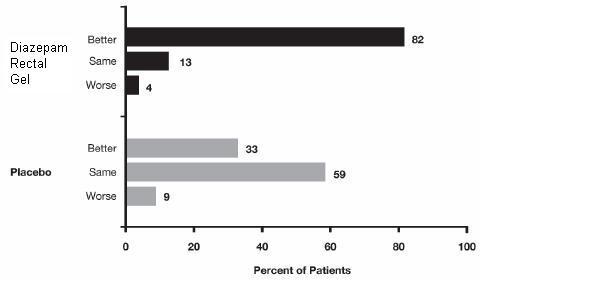

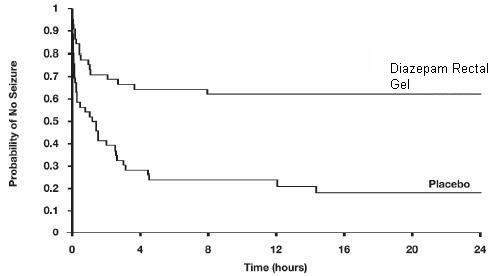

A randomized, double-blind study compared sequential doses of diazepam rectal gel and placebo in 91 patients (47 children, 44 adults) exhibiting the appropriate seizure profile. The first dose was given at the onset of an identified episode. Children were dosed again four hours after the first dose and were observed for a total of 12 hours. Adults were dosed at four and 12 hours after the first dose and were observed for a total of 24 hours. Primary outcomes for this study were seizure frequency during the period of observation and a global assessment that took into account the severity and nature of the seizures as well as their frequency.

The median seizure frequency for the diazepam rectal gel treated group was zero seizures per hour, compared to a median seizure frequency of 0.3 seizures per hour for the placebo group, a difference that was statistically significant (p <0.0001). All three categories of the global assessment (seizure frequency, seizure severity, and “overall”) were also found to be statistically significant in favor of diazepam rectal gel (p < 0.0001). The following histogram displays the results for the “overall” category of the global assessment.

Patients treated with diazepam rectal gel experienced prolonged time-to-next-seizure compared to placebo (p = 0.0002) as shown in the following graph.

In addition, 62% of patients treated with diazepam rectal gel were seizure-free during the observation period compared to 20% of placebo patients.

Analysis of response by gender and age revealed no substantial differences between treatment in either of these subgroups. Analysis of response by race was considered unreliable, due to the small percentage of non-Caucasians.

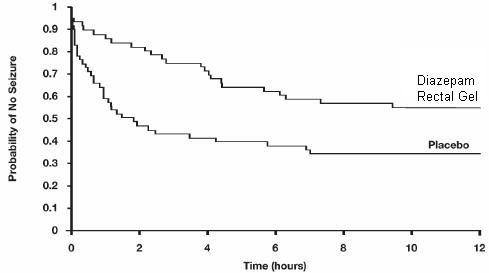

A second double-blind study compared single doses of diazepam rectal gel and placebo in 114 patients (53 children, 61 adults). The dose was given at the onset of the identified episode and patients were observed for a total of 12 hours. The primary outcome in this study was seizure frequency. The median seizure frequency for the diazepam rectal gel-treated group was zero seizures per 12 hours, compared to a median seizure frequency of 2.0 seizures per 12 hours for the placebo group, a difference that was statistically significant (p < 0.03). Patients treated with diazepam rectal gel experienced prolonged time-to-next-seizure compared to placebo (p = 0.0072) as shown in the following graph.

In addition, 55% of patients treated with diazepam rectal gel were seizure-free during the observation period compared to 34% of patients receiving placebo. Overall, caregivers judged diazepam rectal gel to be more effective than placebo (p = 0.018), based on a 10 centimeter visual analog scale. In addition, investigators also evaluated the effectiveness of diazepam rectal gel and judged diazepam rectal gel to be more effective than placebo (p < 0.001).

An analysis of response by gender revealed a statistically significant difference between treatments in females but not in males in this study, and the difference between the 2 genders in response to the treatments reached borderline statistical significance. Analysis of response by race was considered unreliable, due to the small percentage of non-Caucasians.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Diazepam rectal gel is a gel formulation of diazepam intended for rectal administration in the management of selected, refractory, patients with epilepsy, on stable regimens of AEDs, who require intermittent use of diazepam to control bouts of increased seizure activity.

Evidence to support the use of diazepam rectal gel was adduced in two controlled trials (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, CLINICAL STUDIES subsection) that enrolled patients with partial onset or generalized convulsive seizures who were identified jointly by their caregivers and physicians as suffering intermittent and periodic episodes of markedly increased seizure activity, sometimes heralded by nonconvulsive symptoms, that for the individual patient were characteristic and were deemed by the prescriber to be of a kind for which a benzodiazepine would ordinarily be administered acutely. Although these clusters or bouts of seizures differed among patients, for any individual patient the clusters of seizure activity were not only stereotypic but were judged by those conducting and participating in these studies to be distinguishable from other seizures suffered by that patient. The conclusion that a patient experienced such unique episodes of seizure activity was based on historical information.

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

General

Diazepam rectal gel should only be administered by caregivers who in the opinion of the prescribing physician 1) are able to distinguish the distinct cluster of seizures (and/or the events presumed to herald their onset) from the patient’s ordinary seizure activity, 2) have been instructed and judged to be competent to administer the treatment rectally, 3) understand explicitly which seizure manifestations may or may not be treated with diazepam rectal gel, and 4) are able to monitor the clinical response and recognize when that response is such that immediate professional medical evaluation is required.

CNS Depression

Because diazepam rectal gel produces CNS depression, patients receiving this drug who are otherwise capable and qualified to do so should be cautioned against engaging in hazardous occupations requiring mental alertness, such as operating machinery, driving a motor vehicle, or riding a bicycle until they have completely returned to their level of baseline functioning.

Although diazepam rectal gel is indicated for use solely on an intermittent basis, the potential for a synergistic CNS-depressant effect when used simultaneously with alcohol or other CNS depressants must be considered by the prescribing physician, and appropriate recommendations made to the patient and/or caregiver.

Prolonged CNS depression has been observed in neonates treated with diazepam. Therefore, diazepam rectal gel is not recommended for use in children under six months of age.

Pregnancy Risks

No clinical studies have been conducted with diazepam rectal gel in pregnant women. Data from several sources raise concerns about the use of diazepam during pregnancy.

Animal Findings: Diazepam has been shown to be teratogenic in mice and hamsters when given orally at single doses of 100 mg/kg or greater (approximately eight times the maximum recommended human dose [MRHD=1 mg/kg/day] or greater on a mg/m2 basis). Cleft palate and exencephaly are the most common and consistently reported malformations produced in these species by administration of high, maternally-toxic doses of diazepam during organogenesis. Rodent studies have indicated that prenatal exposure to diazepam doses similar to those used clinically can produce longterm changes in cellular immune responses, brain neurochemistry, and behavior.

General Concerns and Considerations About Anticonvulsants: Reports suggest an association between the use of anticonvulsant drugs by women with epilepsy and an elevated incidence of birth defects in children born to these women. Data are more extensive with respect to phenytoin and phenobarbital, but a smaller number of systematic or anecdotal reports suggest a possible similar association with the use of all known anticonvulsant drugs.

The reports suggesting an elevated incidence of birth defects in children of drug treated epileptic women cannot be regarded as adequate to prove a definite cause and effect relationship. There are intrinsic methodologic problems in obtaining adequate data on drug teratogenicity in humans; the possibility also exists that other factors, e.g., genetic factors or the epileptic condition itself, may be more important than drug therapy in leading to birth defects. The great majority of mothers on anticonvulsant medication deliver normal infants. It is important to note that anticonvulsant drugs should not be discontinued in patients in whom the drug is administered to prevent seizures because of the strong possibility of precipitating status epilepticus with attendant hypoxia and threat to life. In individual cases where the severity and frequency of the seizure disorder are such that the removal of medication does not pose a serious threat to the patient, discontinuation of the drug may be considered prior to and during pregnancy, although it cannot be said with any confidence that even mild seizures do not pose some hazards to the developing embryo or fetus.

General Concerns About Benzodiazepines: An increased risk of congenital malformations associated with the use of benzodiazepine drugs has been suggested in several studies.

There may also be non-teratogenic risks associated with the use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy. There have been reports of neonatal flaccidity, respiratory and feeding difficulties, and hypothermia in children born to mothers who have been receiving benzodiazepines late in pregnancy. In addition, children born to mothers receiving benzodiazepines on a regular basis late in pregnancy may be at some risk of experiencing withdrawal symptoms during the postnatal period.

Advice Regarding the Use of Diazepam rectal gel in Women of Childbearing Potential: In general, the use of diazepam rectal gel in women of childbearing potential, and more specifically during known pregnancy, should be considered only when the clinical situation warrants the risk to the fetus.

The specific considerations addressed above regarding the use of anticonvulsants in epileptic women of childbearing potential should be weighed in treating or counseling these women.

Because of experience with other members of the benzodiazepine class, diazepam rectal gel is assumed to be capable of causing an increased risk of congenital abnormalities when administered to a pregnant woman during the first trimester. The possibility that a woman of childbearing potential may be pregnant at the time of institution of therapy should be considered. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus. Patients should also be advised that if they become pregnant during therapy or intend to become pregnant they should communicate with their physician about the desirability of discontinuing the drug.

Withdrawal Symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms of the barbiturate type have occurred after the discontinuation of regular use of benzodiazepines (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE section).

Chronic Use

Diazepam rectal gel is not recommended for chronic, daily use as an anticonvulsant because of the potential for development of tolerance to diazepam. Chronic daily use of diazepam may increase the frequency and/or severity of tonic clonic seizures, requiring an increase in the dosage of standard anticonvulsant medication. In such cases, abrupt withdrawal of chronic diazepam may also be associated with a temporary increase in the frequency and/or severity of seizures.

-

PRECAUTIONS

Caution in Renally Impaired Patients

Metabolites of diazepam rectal gel are excreted by the kidneys; to avoid their excess accumulation, caution should be exercised in the administration of the drug to patients with impaired renal function.

Caution in Hepatically Impaired Patients

Concomitant liver disease is known to decrease the clearance of diazepam (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populations, Hepatic Impairment). Therefore, diazepam rectal gel should be used with caution in patients with liver disease.

Use in Pediatrics

The controlled trials demonstrating the effectiveness of diazepam rectal gel included children two years of age and older. Clinical studies have not been conducted to establish the efficacy and safety of diazepam rectal gel in children under two years of age.

Use in Patients with Compromised Respiratory Function

Diazepam rectal gel should be used with caution in patients with compromised respiratory function related to a concurrent disease process (e.g., asthma, pneumonia) or neurologic damage.

Use in Elderly

In elderly patients diazepam rectal gel should be used with caution due to an increase in halflife with a corresponding decrease in the clearance of free diazepam. It is also recommended that the dosage be decreased to reduce the likelihood of ataxia or oversedation.

Information to be Communicated by the Prescriber to the Caregiver

Prescribers are strongly advised to take all reasonable steps to ensure that caregivers fully understand their role and obligations vis a vis the administration of diazepam rectal gel to individuals in their care. Prescribers should routinely discuss the steps in the Patient/Caregiver Package Insert (see Patient/Caregiver Insert printed at the end of the product labeling and also included in the product carton). The successful and safe use of diazepam rectal gel depends in large measure on the competence and performance of the caregiver.

Prescribers should advise caregivers that they expect to be informed immediately if a patient develops any new findings which are not typical of the patient’s characteristic seizure episode.

Interference With Cognitive and Motor Performance: Because benzodiazepines have the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that diazepam rectal gel therapy does not affect them adversely.

Pregnancy: Patients should be advised to notify their physician if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy with diazepam rectal gel (see WARNINGS section).

Nursing: Because diazepam and its metabolites may be present in human breast milk for prolonged periods of time after acute use of diazepam rectal gel, patients should be advised not to breast-feed for an appropriate period of time after receiving treatment with diazepam rectal gel.

Concomitant Medication

Although diazepam rectal gel is indicated for use solely on an intermittent basis, the potential for a synergistic CNS-depressant effect when used simultaneously with alcohol or other CNS-depressants must be considered by the prescribing physician, and appropriate recommendations made to the patient and/or caregiver.

Drug Interactions

If diazepam rectal gel is to be combined with other psychotropic agents or other CNS depressants, careful consideration should be given to the pharmacology of the agents to be employed particularly with known compounds which may potentiate the action of diazepam, such as phenothiazines, narcotics, barbiturates, MAO inhibitors and other antidepressants.

The clearance of diazepam and certain other benzodiazepines can be delayed in association with cimetidine administration. The clinical significance of this is unclear.

Valproate may potentiate the CNS-depressant effects of diazepam.

There have been no clinical studies or reports in literature to evaluate the interaction of rectally administered diazepam with other drugs. As with all drugs, the potential for interaction by a variety of mechanisms is a possibility.

Effect of Other Drugs on Diazepam Metabolism:In vitro studies using human liver preparations suggest that CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 are the principal isozymes involved in the initial oxidative metabolism of diazepam. Therefore, potential interactions may occur when diazepam is given concurrently with agents that affect CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 activity. Potential inhibitors of CYP2C19 (e.g., cimetidine, quinidine, and tranylcypromine) and CYP3A4 (e.g., ketoconazole, troleandomycin, and clotrimazole) could decrease the rate of diazepam elimination, while inducers of CYP2C19 (e.g., rifampin) and CYP3A4 (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, dexamethasone and phenobarbital) could increase the rate of elimination of diazepam.

Effect of Diazepam on the Metabolism of Other Drugs: There are no reports as to which isozymes could be inhibited or induced by diazepam. But, based on the fact that diazepam is a substrate for CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, it is possible that diazepam may interfere with the metabolism of drugs which are substrates for CYP2C19, (e.g. omeprazole, propranolol, and imipramine) and CYP3A4 (e.g. cyclosporine, paclitaxel, terfenadine, theophylline, and warfarin) leading to a potential drug-drug interaction.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

The carcinogenic potential of rectal diazepam has not been evaluated. In studies in which mice and rats were administered diazepam in the diet at a dose of 75 mg/kg/day (approximately six and 12 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose [MRHD=1 mg/kg/day] on a mg/m2 basis) for 80 and 104 weeks, respectively, an increased incidence of liver tumors was observed in males of both species.

The data currently available are inadequate to determine the mutagenic potential of diazepam.

Reproduction studies in rats showed decreases in the number of pregnancies and in the number of surviving offspring following administration of an oral dose of 100 mg/kg/day (approximately 16 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) prior to and during mating and throughout gestation and lactation. No adverse effects on fertility or offspring viability were noted at a dose of 80 mg/kg/day (approximately 13 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Diazepam rectal gel adverse event data were collected from double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and open-label studies. The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and transient in nature.

Two patients who received diazepam rectal gel died seven to 15 weeks following treatment; neither of these deaths was deemed related to diazepam rectal gel.

The most frequent adverse event reported to be related to diazepam rectal gel in the two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies was somnolence (23%). Less frequent adverse events were dizziness, headache, pain, abdominal pain, nervousness, vasodilatation, diarrhea, ataxia, euphoria, incoordination, asthma, rhinitis, and rash, which occurred in approximately 2-5% of patients.

Approximately 1.4% of the 573 patients who received diazepam rectal gel in clinical trials of epilepsy discontinued treatment because of an adverse event. The adverse event most frequently associated with discontinuation (occurring in three patients) was somnolence. Other adverse events most commonly associated with discontinuation and occurring in two patients were hypoventilation and rash. Adverse events occurring in one patient were asthenia, hyperkinesia, incoordination, vasodilatation and urticaria. These events were judged to be related to diazepam rectal gel.

In the two domestic double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies, the proportion of patients who discontinued treatment because of adverse events was 2% for the group treated with diazepam rectal gel, versus 2% for the placebo group. In the diazepam rectal gel group, the adverse events considered the primary reason for discontinuation were different in the two patients who discontinued treatment; one discontinued due to rash and one discontinued due to lethargy. The primary reason for discontinuation in the patients treated with placebo was lack of effect.

Adverse Event Incidence in Controlled Clinical Trials

Table 1 lists treatment-emergent signs and symptoms that occurred in > 1% of patients enrolled in parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials and were numerically more common in the diazepam rectal gel group. Adverse events were usually mild or moderate in intensity.

The prescriber should be aware that these figures, obtained when diazepam rectal gel was added to concurrent antiepileptic drug therapy, cannot be used to predict the frequency of adverse events in the course of usual medical practice when patient characteristics and other factors may differ from those prevailing during clinical studies. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be directly compared with figures obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, or investigators. An inspection of these frequencies, however, does provide the prescribing physician with one basis to estimate the relative contribution of drug and non-drug factors to the adverse event incidences in the population studied.

TABLE 1: Treatment-Emergent Signs And Symptoms That Occurred In > 1% Of Patients Enrolled In Parallel-Group, Placebo-Controlled Trials And Were Numerically More Common In The Diazepam Rectal Gel Group Body System

COSTART

TermDiazepam Rectal Gel

N = 101

%Placebo

N = 104

%Body As A Whole

Headache

5%

4%

Cardiovascular

Vasodilatation

2%

0%

Digestive

Diarrhea

4%

<1%

Nervous

Ataxia

3%

<1%

Dizziness

3%

2%

Euphoria

3%

0%

Incoordination

3%

0%

Somnolence

23%

8%

Respiratory

Asthma

2%

0%

Skin and Appendages

Rash

3%

0%

Other events reported by 1% or more of patients treated in controlled trials but equally or more frequent in the placebo group than in the diazepam rectal gel group were abdominal pain, pain, nervousness, and rhinitis. Other events reported by fewer than 1% of patients were infection, anorexia, vomiting, anemia, lymphadenopathy, grand mal convulsion, hyperkinesia, cough increased, pruritus, sweating, mydriasis, and urinary tract infection.

The pattern of adverse events was similar for different age, race and gender groups.

Other Adverse Events Observed During All Clinical Trials:

Diazepam rectal gel has been administered to 573 patients with epilepsy during all clinical trials, only some of which were placebo-controlled. During these trials, all adverse events were recorded by the clinical investigators using terminology of their own choosing. To provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals having adverse events, similar types of events were grouped into a smaller number of standardized categories using modified COSTART dictionary terminology. These categories are used in the listing below. All of the events listed below occurred in at least 1% of the 573 individuals exposed to diazepam rectal gel.

All reported events are included except those already listed above, events unlikely to be drug-related, and those too general to be informative. Events are included without regard to determination of a causal relationship to diazepam.

BODY AS A WHOLE: Asthenia

CARDIOVASCULAR: Hypotension, vasodilatation

NERVOUS: Agitation, confusion, convulsion, dysarthria, emotional lability, speech disorder, thinking abnormal, vertigo

RESPIRATORY: Hiccup

The following infrequent adverse events were not seen with diazepam rectal gel but have been reported previously with diazepam use: depression, slurred speech, syncope, constipation, changes in libido, urinary retention, bradycardia, cardiovascular collapse, nystagmus, urticaria, neutropenia and jaundice.

Paradoxical reactions such as acute hyperexcited states, anxiety, hallucinations, increased muscle spasticity, insomnia, rage, sleep disturbances and stimulation have been reported with diazepam; should these occur, use of diazepam rectal gel should be discontinued.

-

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

Diazepam is a Schedule IV controlled substance and can produce drug dependence. It is recommended that patients be treated with diazepam rectal gel no more frequently than every five days and no more than five times per month.

Addiction-prone individuals (such as drug addicts or alcoholics) should be under careful surveillance when receiving diazepam or other psychotropic agents because of the predisposition of such patients to habituation and dependence.

Abrupt discontinuation of diazepam following chronic regular use has resulted in withdrawal symptoms, similar in character to those noted with barbiturates and alcohol (convulsions, tremor, abdominal and muscle cramps, vomiting and sweating). The more severe withdrawal symptoms have usually been limited to those patients who had received excessive doses over an extended period of time. Generally milder withdrawal symptoms (e.g., dysphoria and insomnia) have been reported following abrupt discontinuation of benzodiazepines taken continuously at therapeutic levels for several months.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Two patients in the clinical studies received more than twice the target dose; no adverse events were reported.

Previous reports of diazepam overdosage have shown that manifestations of diazepam overdosage include somnolence, confusion, coma, and diminished reflexes. Respiration, pulse and blood pressure should be monitored, as in all cases of drug overdosage, although, in general, these effects have been minimal. General supportive measures should be employed, along with intravenous fluids, and an adequate airway maintained. Hypotension may be combated by the use of levarterenol or metaraminol. Dialysis is of limited value.

Flumazenil, a specific benzodiazepine-receptor antagonist, is indicated for the complete or partial reversal of the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and may be used in situations when an overdose with a benzodiazepine is known or suspected. Prior to the administration of flumazenil, necessary measures should be instituted to secure airway, ventilation and intravenous access. Flumazenil is intended as an adjunct to, not as a substitute for, proper management of benzodiazepine overdose. Patients treated with flumazenil should be monitored for resedation, respiratory depression and other residual benzodiazepine effects for an appropriate period after treatment. The prescriber should be aware of a risk of seizure in association with flumazenil treatment, particularly in long-term benzodiazepine users and in cyclic antidepressant overdose. The complete flumazenil package insert, including CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, should be consulted prior to use.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (see also Patient/Caregiver Package Insert)

This section is intended primarily for the prescriber; however, the prescriber should also be aware of the dosing information and directions for use provided in the patient package insert.

A decision to prescribe diazepam rectal gel involves more than the diagnosis and the selection of the correct dose for the patient.

First, the prescriber must be convinced from historical reports and/or personal observations that the patient exhibits the characteristic identifiable seizure cluster that can be distinguished from the patient’s usual seizure activity by the caregiver who will be responsible for administering diazepam rectal gel.

Second, because diazepam rectal gel is only intended for adjunctive use, the prescriber must ensure that the patient is receiving an optimal regimen of standard anti-epileptic drug treatment and is, nevertheless, continuing to experience these characteristic episodes.

Third, because a non-health professional will be obliged to identify episodes suitable for treatment, make the decision to administer treatment upon that identification, administer the drug, monitor the patient, and assess the adequacy of the response to treatment, a major component of the prescribing process involves the necessary instruction of this individual.

Fourth, the prescriber and caregiver must have a common understanding of what is and is not an episode of seizures that is appropriate for treatment, the timing of administration in relation to the onset of the episode, the mechanics of administering the drug, how and what to observe following administration, and what would constitute an outcome requiring immediate and direct medical attention.

Calculating Prescribed Dose

The diazepam rectal gel dose should be individualized for maximum beneficial effect. The recommended dose of diazepam rectal gel is 0.2-0.5 mg/kg depending on age. See the dosing table for specific recommendations.

Age (years)

Recommended Dose

2 through 5

0.5 mg/kg

6 through 11

0.3 mg/kg

12 and older

0.2 mg/kg

Because diazepam rectal gel is provided as unit doses of 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, and 20 mg, the prescribed dose is obtained by rounding upward to the next available dose. The following table provides acceptable weight ranges for each dose and age category, such that patients will receive between 90% and 180% of the calculated recommended dose. The safety of this strategy has been established in clinical trials.

2 - 5 Years

0.5 mg/kg6 - 11 Years

0.3 mg/kg12+ Years

0.2 mg/kgWeight

(kg)Dose

(mg)Weight

(kg)Dose

(mg)Weight

(kg)Dose

(mg)6 to 10

5

10 to 16

5

14 to 25

5

11 to 15

7.5

17 to 25

7.5

26 to 37

7.5

16 to 20

10

26 to 33

10

38 to 50

10

21 to 25

12.5

34 to 41

12.5

51 to 62

12.5

26 to 30

15

42 to 50

15

63 to 75

15

31 to 35

17.5

51 to 58

17.5

76 to 87

17.5

36 to 44

20

59 to 74

20

88 to 111

20

The rectal delivery system includes a plastic applicator with a flexible, molded tip available in two lengths. The diazepam rectal gel 10 mg syringe is available with a 4.4 cm tip and the diazepam rectal gel 20 mg syringe is available with a 6.0 cm tip. Diazepam rectal gel 2.5 mg is also available with a 4.4 cm tip.

In elderly and debilitated patients, it is recommended that the dosage be adjusted downward to reduce the likelihood of ataxia or oversedation.

The prescribed dose of diazepam rectal gel should be adjusted by the physician periodically to reflect changes in the patient’s age or weight.

The diazepam rectal gel 2.5 mg dose may also be used as a partial replacement dose for patients who may expel a portion of the first dose.

Additional Dose

The prescriber may wish to prescribe a second dose of diazepam rectal gel. A second dose, when required, may be given 4-12 hours after the first dose.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Diazepam Rectal Gel rectal delivery system is a non-sterile, prefilled, unit dose, rectal delivery system. The rectal delivery system includes a plastic applicator with a flexible, molded tip available in two lengths, designated for convenience as 10 mg delivery system and 20 mg delivery system. The available doses from 20 mg delivery system are 12.5 mg, 15 mg, 17.5 mg, and 20 mg. The available doses from 10 mg delivery system are 5 mg, 7.5 mg and 10 mg. The Diazepam Rectal Gel delivery system is available in the following three presentations:

Diazepam Rectal Gel

Rectal Tip Size

NDC

2.5 mg Twin Pack

4.4 cm

NDC: 0093-6137-32

Diazepam Rectal Gel

Rectal Tip Size

NDC

10 mg Delivery

System Twin Pack4.4 cm

NDC: 0093-6138-32

20 mg Delivery

System Twin Pack6.0 cm

NDC: 0093-6139-32

Each twin pack contains two Diazepam Rectal Gel delivery systems, two packets of lubricating jelly, and administration and disposal Instructions available on the bottom of the package. Diazepam Rectal Gel is also packed with Instructions for Caregivers upon receipt from pharmacy.Store at 25°C (77°F); excursions permitted to 15-30°C (59-86°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature].

Diazepam Rectal Gel 10 mg delivery system and 20 mg delivery system

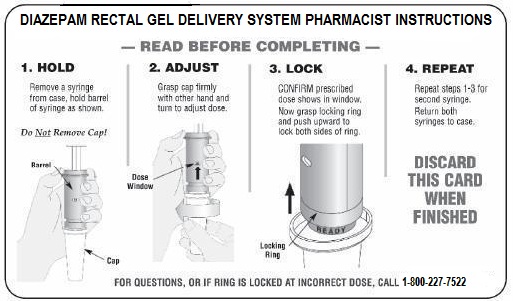

INSTRUCTIONS FOR CAREGIVERS UPON RECEIPT FROM PHARMACY

- Remove the syringe from the case.

- Confirm the dose prescribed by your doctor is visible and if known, is correct.

FOR EACH SYRINGE:

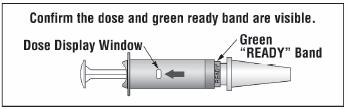

- Confirm that the prescribed dose is visible in the dose display window.

- Confirm that the green “READY” band is visible.

- Return the syringe to the case.

SEE PHARMACIST IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS ABOUT THESE INSTRUCTIONS.

The instructions are also available on the bottom of each drug product package.

CAUTION: Federal law prohibits the transfer of this drug to any person other than the patient for whom it was prescribed.

Valium® is a registered trademark of Roche Pharmaceuticals.

Distributed by:

TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC.

North Wales, PA 19454Manufactured By:

DPT Laboratories, LTD.

San Antonio, TX 782159435000

Rev. A 2/2015 -

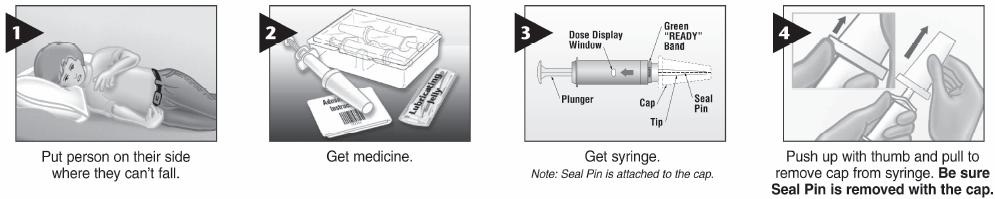

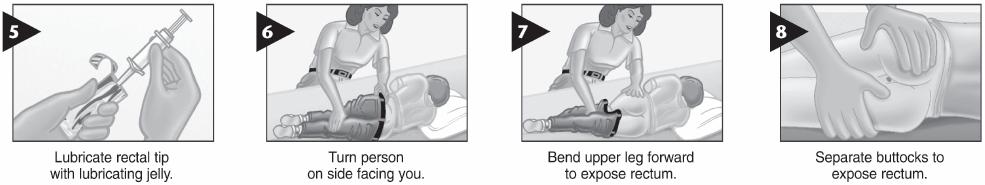

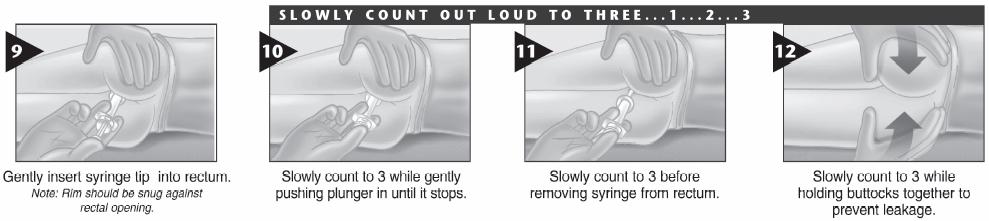

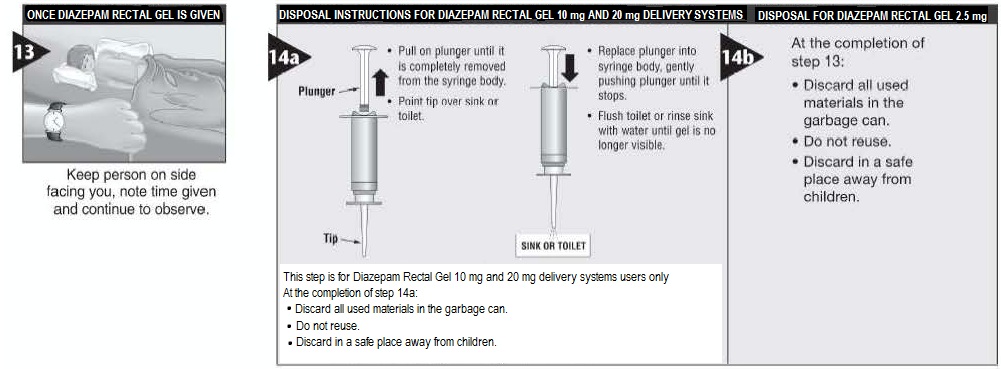

ADMINISTRATION AND DISPOSAL INSTRUCTIONS

Diazepam Rectal Gel

Diazepam Rectal Gel Rectal Delivery SystemCIV

IMPORTANT

Read first before using

To the caregiver using Diazepam Rectal Gel:

Please do not give Diazepam Rectal Gel until:

- 1. You have thoroughly read these instructions

- 2. Reviewed administration steps with the doctor

- 3. Understand the directions

To the caregiver using Diazepam Rectal Gel 10 mg rectal delivery system or 20 mg rectal delivery system:

Please do not give Diazepam Rectal Gel 10 mg rectal delivery system or 20 mg rectal delivery system until:

1. You have confirmed:

- 1. Prescribed dose is visible and if known, is correct

- 2. green "ready" band is visible

2. You have thoroughly read these instructions

3. Reviewed administration steps with the doctor

4. Understand the directions

Please do not administer Diazepam Rectal Gel until you feel comfortable with how to use Diazepam Rectal Gel. The doctor will tell you exactly when to use Diazepam Rectal Gel. When you use Diazepam Rectal Gel correctly and safely you will help bring seizures under control. Be sure to discuss every aspect of your role with the doctor. If you are not comfortable, then discuss your role with the doctor again.

To help the person with seizures:

√ You must be able to tell the difference between cluster and ordinary seizures.

√ You must be comfortable and satisfied that you are able to give Diazepam Rectal

Gel.√ You need to agree with the doctor on the exact conditions when to treat with

Diazepam Rectal Gel.√ You must know how and for how long you should check the person after giving

Diazepam Rectal Gel.To know what responses to expect:

√ You need to know how soon seizures should stop or decrease in frequency after

giving Diazepam Rectal Gel.√ You need to know what you should do if the seizures do not stop or there is a

change in the person’s breathing, behavior or condition that alarms you.If you have any question or feel unsure about using the treatment, CALL THE DOCTOR before using Diazepam Rectal Gel.

When to treat. Based on the doctor’s directions or prescription. Your doctor may prescribe a second dose of Diazepam Rectal Gel. If a second dose is needed, give it 4 hours to 12 hours after the first dose.________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

Special considerations.

Diazepam Rectal Gel should be used with caution:

- In people with respiratory (breathing) difficulties (e.g., asthma or pneumonia)

- In the elderly

- In women of child bearing potential, pregnancy and nursing mothers

Discuss beforehand with the doctor any additional steps you may need to take if there is leakage of Diazepam Rectal Gel or a bowel movement.

Patient’s Diazepam Rectal Gel dosage is: __________mg

Patient’s resting breathing rate_________ Patient’s current weight____________

Confirm current weight is still the same as when Diazepam Rectal Gel was prescribed____________

Check expiration date and always remove cap before using. Be sure seal pin is removed with the cap.

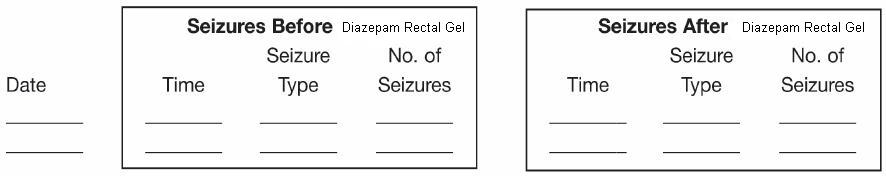

TREATMENT 1

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Important things to tell the doctor.

Things to do after treatment with Diazepam Rectal Gel.

Stay with the person for 4 hours and make notes on the following:

- Changes in resting breathing rate__________________________

- Changes in color ______________________________________

- Possible side effects from treatment_______________________

- Your doctor may prescribe a second dose of Diazepam Rectal Gel. If a second dose is needed, give it 4 hours to 12 hours after the first dose.

TREATMENT 2

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Important things to tell the doctor.

Things to do after treatment with Diazepam Rectal Gel.

Stay with the person for 4 hours and make notes on the following:

- 1. Changes in resting breathing rate_________________________

- 2. Changes in color ___________________________________

- 3. Possible side effects from treatment________________________

HOW TO ADMINISTER AND DISPOSAL

Diazepam Rectal Gel CIV

Distributed by:

TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC.

North Wales, PA 19454

Manufactured By:

DPT Laboratories, LTD.

San Antonio, TX 78215Rev. A 2/2015

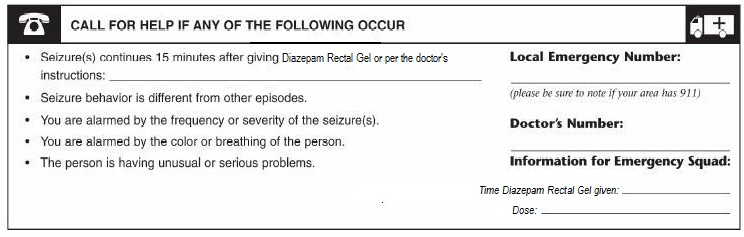

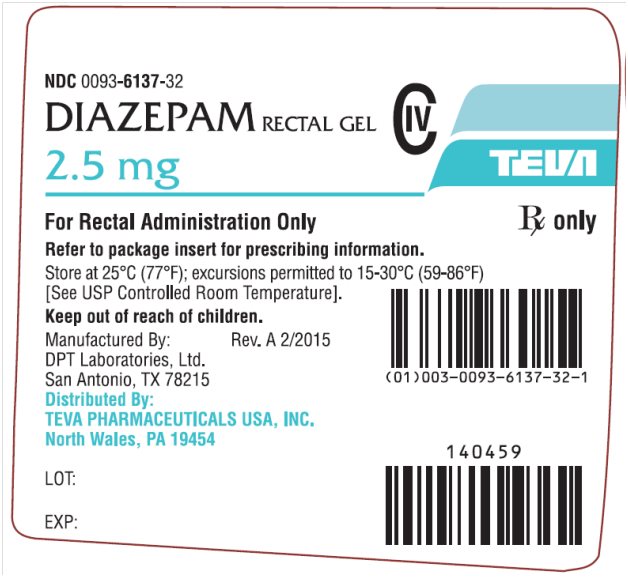

- Package/Label Display Panel

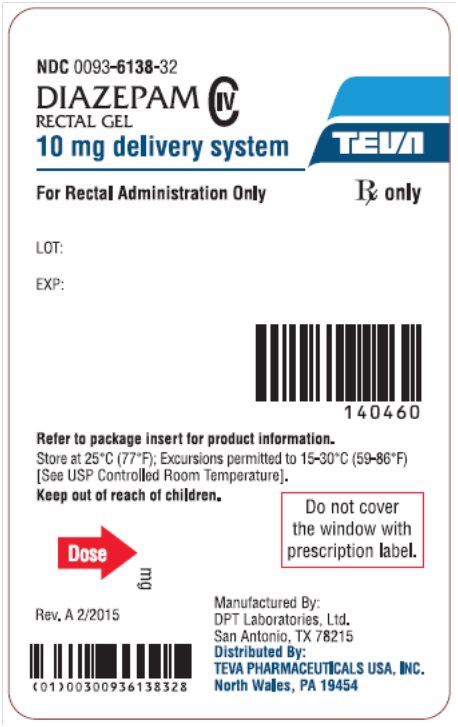

- Package/Label Display Panel

- Package/Label Display Panel

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

DIAZEPAM

diazepam gelProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0093-6137 Route of Administration RECTAL DEA Schedule CIV Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength DIAZEPAM (UNII: Q3JTX2Q7TU) (DIAZEPAM - UNII:Q3JTX2Q7TU) DIAZEPAM 2.5 mg in 0.5 mL Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength PROPYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 6DC9Q167V3) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) SODIUM BENZOATE (UNII: OJ245FE5EU) BENZYL ALCOHOL (UNII: LKG8494WBH) BENZOIC ACID (UNII: 8SKN0B0MIM) WATER (UNII: 059QF0KO0R) Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0093-6137-32 2 in 1 PACKAGE 10/01/2010 10/31/2020 1 0.5 mL in 1 SYRINGE, PLASTIC; Type 2: Prefilled Drug Delivery Device/System (syringe, patch, etc.) Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA authorized generic NDA020648 10/01/2010 10/31/2020 DIAZEPAM

diazepam gelProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0093-6138 Route of Administration RECTAL DEA Schedule CIV Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength DIAZEPAM (UNII: Q3JTX2Q7TU) (DIAZEPAM - UNII:Q3JTX2Q7TU) DIAZEPAM 10 mg in 2 mL Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength PROPYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 6DC9Q167V3) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) SODIUM BENZOATE (UNII: OJ245FE5EU) BENZYL ALCOHOL (UNII: LKG8494WBH) BENZOIC ACID (UNII: 8SKN0B0MIM) WATER (UNII: 059QF0KO0R) Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0093-6138-32 2 in 1 PACKAGE 09/03/2010 10/31/2021 1 2 mL in 1 SYRINGE, PLASTIC; Type 2: Prefilled Drug Delivery Device/System (syringe, patch, etc.) Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA authorized generic NDA020648 09/03/2010 10/31/2021 DIAZEPAM

diazepam gelProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0093-6139 Route of Administration RECTAL DEA Schedule CIV Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength DIAZEPAM (UNII: Q3JTX2Q7TU) (DIAZEPAM - UNII:Q3JTX2Q7TU) DIAZEPAM 20 mg in 4 mL Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength PROPYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 6DC9Q167V3) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) SODIUM BENZOATE (UNII: OJ245FE5EU) BENZYL ALCOHOL (UNII: LKG8494WBH) BENZOIC ACID (UNII: 8SKN0B0MIM) WATER (UNII: 059QF0KO0R) Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0093-6139-32 2 in 1 PACKAGE 09/03/2010 09/30/2021 1 4 mL in 1 SYRINGE, PLASTIC; Type 2: Prefilled Drug Delivery Device/System (syringe, patch, etc.) Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA authorized generic NDA020648 09/03/2010 09/30/2021 Labeler - Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (001627975) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations DPT Laboratories, Ltd. 832224526 MANUFACTURE(0093-6137, 0093-6138, 0093-6139)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.