ATOVAQUONE AND PROGUANIL HCL- atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride tablet, film coated

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Bryant Ranch Prepack. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets.

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets

Initial U.S. Approval: 2000INDICATIONS AND USAGE

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

- Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets should be taken with food or a milky drink.

Prophylaxis (2.1):

- Start prophylaxis 1 or 2 days before entering a malaria‑endemic area and continue daily during the stay and for 7 days after return.

- Adults: One adult strength tablet per day.

Treatment (2.2):

- Adults: Four adult strength tablets as a single daily dose for 3 days.

Renal Impairment (2.3):

- Do not use for prophylaxis of malaria in patients with severe renal impairment.

- Use with caution for treatment of malaria in patients with severe renal impairment.

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Tablets (adult strength): 250 mg atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil hydrochloride. (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Atovaquone absorption may be reduced in patients with diarrhea or vomiting. If used in patients who are vomiting, parasitemia should be closely monitored and the use of an antiemetic considered. In patients with severe or persistent diarrhea or vomiting, alternative antimalarial therapy may be required. (5.1)

- In mixed P. falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infection, P. vivax relapse occurred commonly when patients were treated with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets alone. (5.2)

- In the event of recrudescent P. falciparum infections after treatment or prophylaxis failure, patients should be treated with a different blood schizonticide. (5.2)

- Elevated liver laboratory tests and cases of hepatitis and hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation have been reported with prophylactic use. (5.3)

- Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets have not been evaluated for the treatment of cerebral malaria or other severe manifestations of complicated malaria. Patients with severe malaria are not candidates for oral therapy. (5.4)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

- Prophylaxis: common adverse reactions (≥4%) in adults were diarrhea, dreams, oral ulcers, and headache; these events occurred in a similar or lower proportion of subjects receiving Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets than an active comparator. Common adverse reactions (≥5%) in pediatric patients included abdominal pain, headache, cough, and vomiting. (6.1)

- Treatment: common adverse reactions (≥5%) in adolescents and adults were abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, diarrhea, asthenia, anorexia, and dizziness. Common adverse reactions (≥6%) in pediatric patients included vomiting, pruritus, and diarrhea. (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact GlaxoSmithKline at 1-888-825-5249 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

- Administration with rifampin or rifabutin is known to reduce atovaquone concentrations; concomitant use with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets is not recommended. (7.1)

- Proguanil may potentiate anticoagulant effect of warfarin and other coumarin-based anticoagulants. Caution advised when initiating or withdrawing Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets in patients on anticoagulants; coagulation tests should be closely monitored. (7.2)

- Tetracycline may reduce atovaquone concentrations; parasitemia should be closely monitored. (7.3)

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION.

Revised: 3/2019

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Prevention of Malaria

1.2 Treatment of Malaria

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Prevention of Malaria

2.2 Treatment of Acute Malaria

2.3 Renal Impairment

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

4.1 Hypersensitivity

4.2 Severe Renal Impairment

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Vomiting and Diarrhea

5.2 Relapse of Infection

5.3 Hepatotoxicity

5.4 Severe or Complicated Malaria

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Rifampin/Rifabutin

7.2 Anticoagulants

7.3 Tetracycline

7.4 Metoclopramide

7.5 Indinavir

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Renal Impairment

8.7 Hepatic Impairment

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

12.4 Microbiology

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Prevention of P. falciparum Malaria

14.2 Treatment of Acute, Uncomplicated P. falciparum Malaria Infections

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Prevention of Malaria

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are indicated for the prophylaxis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria, including in areas where chloroquine resistance has been reported.

1.2 Treatment of Malaria

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are indicated for the treatment of acute, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets have been shown to be effective in regions where the drugs chloroquine, halofantrine, mefloquine, and amodiaquine may have unacceptable failure rates, presumably due to drug resistance.

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The daily dose should be taken at the same time each day with food or a milky drink. In the event of vomiting within 1 hour after dosing, a repeat dose should be taken.

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets may be crushed and mixed with condensed milk just prior to administration to patients who may have difficulty swallowing tablets.

2.1 Prevention of Malaria

Start prophylactic treatment with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets 1 or 2 days before entering a malaria-endemic area and continue daily during the stay and for 7 days after return.

Adults: One Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablet (adult strength = 250 mg atovaquone/100 mg proguanil hydrochloride) per day.

2.2 Treatment of Acute Malaria

Adults: Four Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets (adult strength; total daily dose 1 g atovaquone/400 mg proguanil hydrochloride) as a single daily dose for 3 consecutive days.

2.3 Renal Impairment

Do not use Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets for malaria prophylaxis in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) [see Contraindications (4.2)]. Use with caution for the treatment of malaria in patients with severe renal impairment, only if the benefits of the 3-day treatment regimen outweigh the potential risks associated with increased drug exposure. No dosage adjustments are needed in patients with mild (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min) or moderate (creatinine clearance 30 to 50 mL/min) renal impairment. [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3).]

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

4.1 Hypersensitivity

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are contraindicated in individuals with known hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis, erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome, angioedema, vasculitis) to atovaquone or proguanil hydrochloride or any component of the formulation.

4.2 Severe Renal Impairment

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are contraindicated for prophylaxis of P. falciparum malaria in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) because of pancytopenia in patients with severe renal impairment treated with proguanil [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6), and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Vomiting and Diarrhea

Absorption of atovaquone may be reduced in patients with diarrhea or vomiting. If Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are used in patients who are vomiting, parasitemia should be closely monitored and the use of an antiemetic considered. [See Dosage and Administration (2).] Vomiting occurred in up to 19% of pediatric patients given treatment doses of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. In the controlled clinical trials, 15.3% of adults received an antiemetic when they received atovaquone/proguanil and 98.3% of these patients were successfully treated. In patients with severe or persistent diarrhea or vomiting, alternative antimalarial therapy may be required.

5.2 Relapse of Infection

In mixed P. falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections, P. vivax parasite relapse occurred commonly when patients were treated with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets alone.

In the event of recrudescent P. falciparum infections after treatment with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets or failure of chemoprophylaxis with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets, patients should be treated with a different blood schizonticide.

5.3 Hepatotoxicity

Elevated liver laboratory tests and cases of hepatitis and hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation have been reported with prophylactic use of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets.

5.4 Severe or Complicated Malaria

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets have not been evaluated for the treatment of cerebral malaria or other severe manifestations of complicated malaria, including hyperparasitemia, pulmonary edema, or renal failure. Patients with severe malaria are not candidates for oral therapy.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Because the tablets contain atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride, the type and severity of adverse reactions associated with each of the compounds may be expected. The lower prophylactic doses of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride were better tolerated than the higher treatment doses.

Prophylaxis of P. falciparum Malaria: In 3 clinical trials (2 of which were placebo‑controlled) 381 adults (mean age 31 years) received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for the prophylaxis of malaria; the majority of adults were black (90%) and 79% were male. In a clinical trial for the prophylaxis of malaria, 125 pediatric patients (mean age 9 years) received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride; all subjects were black and 52% were male. Adverse experiences reported in adults and pediatric patients, considered attributable to therapy, occurred in similar proportions of subjects receiving atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride or placebo in all studies. Prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was discontinued prematurely due to a treatment‑related adverse experience in 3 of 381 (0.8%) adults and 0 of 125 pediatric patients.

In a placebo‑controlled study of malaria prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride involving 330 pediatric patients (aged 4 to 14 years) in Gabon, a malaria-endemic area, the safety profile of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was consistent with that observed in the earlier prophylactic studies in adults and pediatric patients. The most common treatment‑emergent adverse events with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride were abdominal pain (13%), headache (13%), and cough (10%). Abdominal pain (13% vs. 8%) and vomiting (5% vs. 3%) were reported more often with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride than with placebo. No patient withdrew from the study due to an adverse experience with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. No routine laboratory data were obtained during this study.

Non‑immune travelers visiting a malaria‑endemic area received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (n = 1,004) for prophylaxis of malaria in 2 active-controlled clinical trials. In one study (n = 493), the mean age of subjects was 33 years and 53% were male; 90% of subjects were white, 6% of subjects were black and the remaining were of other racial/ethnic groups. In the other study (n = 511), the mean age of subjects was 36 years and 51% were female; the majority of subjects (97%) were white. Adverse experiences occurred in a similar or lower proportion of subjects receiving atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride than an active comparator (Table 1). Fewer neuropsychiatric adverse experiences occurred in subjects who received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride than mefloquine. Fewer gastrointestinal adverse experiences occurred in subjects receiving atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride than chloroquine/proguanil. Compared with active comparator drugs, subjects receiving atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride had fewer adverse experiences overall that were attributed to prophylactic therapy (Table 1). Prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was discontinued prematurely due to a treatment‑related adverse experience in 7 of 1,004 travelers.

Table 1. Adverse Experiences in Active-Controlled Clinical Trials of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride for Prophylaxis of P. falciparum Malaria

Percent of Subjects With Adverse Experiencesa

(Percent of Subjects With Adverse Experiences Attributable to Therapy)

Study 1

Study 2

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl

n = 493

(28 days)b

Mefloquine

n = 483

(53 days)b

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl

n = 511

(26 days)b

Chloroquine plus Proguanil

n = 511

(49 days)b

- Diarrhea

38

(8)

36

(7)

34

(5)

39

(7)

- Nausea

14

(3)

20

(8)

11

(2)

18

(7)

- Abdominal pain

17

(5)

16

(5)

14

(3)

22

(6)

- Headache

12

(4)

17

(7)

12

(4)

14

(4)

- Dreams

7

(7)

16

(14)

6

(4)

7

(3)

- Insomnia

5

(3)

16

(13)

4

(2)

5

(2)

- Fever

9

(<1)

11

(1)

8

(<1)

8

(<1)

- Dizziness

5

(2)

14

(9)

7

(3)

8

(4)

- Vomiting

8

(1)

10

(2)

8

(0)

14

(2)

- Oral ulcers

9

(6)

6

(4)

5

(4)

7

(5)

- Pruritus

4

(2)

5

(2)

3

(1)

2

(<1)

- Visual difficulties

2

(2)

5

(3)

3

(2)

3

(2)

- Depression

<1

(<1)

5

(4)

<1

(<1)

1

(<1)

- Anxiety

1

(<1)

5

(4)

<1

(<1)

1

(<1)

- Any adverse experience

64

(30)

69

(42)

58

(22)

66

(28)

- Any neuropsychiatric event

20

(14)

37

(29)

16

(10)

20

(10)

- Any GI event

49

(16)

50

(19)

43

(12)

54

(20)

a Adverse experiences that started while receiving active study drug.

b Mean duration of dosing based on recommended dosing regimens.

In a third active‑controlled study, atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (n = 110) was compared with chloroquine/proguanil (n = 111) for the prophylaxis of malaria in 221 non-immune pediatric patients (2 to 17 years of age). The mean duration of exposure was 23 days for atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride, 46 days for chloroquine, and 43 days for proguanil, reflecting the different recommended dosage regimens for these products. Fewer patients treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride reported abdominal pain (2% vs. 7%) or nausea (<1% vs. 7%) than children who received chloroquine/proguanil. Oral ulceration (2% vs. 2%), vivid dreams (2% vs. <1%), and blurred vision (0% vs. 2%) occurred in similar proportions of patients receiving either atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride or chloroquine/proguanil, respectively. Two patients discontinued prophylaxis with chloroquine/proguanil due to adverse events, while none of those receiving atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride discontinued due to adverse events.

Treatment of Acute, Uncomplicated P. falciparum Malaria: In 7 controlled trials, 436 adolescents and adults received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for treatment of acute, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. The range of mean ages of subjects was 26 to 29 years; 79% of subjects were male. In these studies, 48% of subjects were classified as other racial/ethnic groups, primarily Asian; 42% of subjects were black and the remaining subjects were white. Attributable adverse experiences that occurred in ≥5% of patients were abdominal pain (17%), nausea (12%), vomiting (12%), headache (10%), diarrhea (8%), asthenia (8%), anorexia (5%), and dizziness (5%). Treatment was discontinued prematurely due to an adverse experience in 4 of 436 (0.9%) adolescents and adults treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride.

In 2 controlled trials, 116 pediatric patients (weighing 11 to 40 kg) (mean age 7 years) received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for the treatment of malaria. The majority of subjects were black (72%); 28% were of other racial/ethnic groups, primarily Asian. Attributable adverse experiences that occurred in ≥5% of patients were vomiting (10%) and pruritus (6%). Vomiting occurred in 43 of 319 (13%) pediatric patients who did not have symptomatic malaria but were given treatment doses of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for 3 days in a clinical trial. The design of this clinical trial required that any patient who vomited be withdrawn from the trial. Among pediatric patients with symptomatic malaria treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride, treatment was discontinued prematurely due to an adverse experience in 1 of 116 (0.9%).

In a study of 100 pediatric patients (5 to ˂11 kg body weight) who received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, only diarrhea (6%) occurred in ≥5% of patients as an adverse experience attributable to atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. In 3 patients (3%), treatment was discontinued prematurely due to an adverse experience.

Abnormalities in laboratory tests reported in clinical trials were limited to elevations of transaminases in malaria patients being treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. The frequency of these abnormalities varied substantially across trials of treatment and were not observed in the randomized portions of the prophylaxis trials.

One active-controlled trial evaluated the treatment of malaria in Thai adults (n = 182); the mean age of subjects was 26 years (range 15 to 63 years); 80% of subjects were male. Early elevations of ALT and AST occurred more frequently in patients treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (n = 91) compared to patients treated with an active control, mefloquine (n = 91). On Day 7, rates of elevated ALT and AST with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride and mefloquine (for patients who had normal baseline levels of these clinical laboratory parameters) were ALT 26.7% vs. 15.6%; AST 16.9% vs. 8.6%, respectively. By Day 14 of this 28‑day study, the frequency of transaminase elevations equalized across the 2 groups.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

In addition to adverse events reported from clinical trials, the following events have been identified during postmarketing use of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. Because they are reported voluntarily from a population of unknown size, estimates of frequency cannot be made. These events have been chosen for inclusion due to a combination of their seriousness, frequency of reporting, or potential causal connection to atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride.

Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: Neutropenia and anemia. Pancytopenia in patients with severe renal impairment treated with proguanil [see Contraindications (4.2)].

Immune System Disorders: Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis, angioedema, and urticaria, and vasculitis.

Nervous System Disorders: Seizures and psychotic events (such as hallucinations); however, a causal relationship has not been established.

Gastrointestinal Disorders: Stomatitis.

Hepatobiliary Disorders: Elevated liver laboratory tests, hepatitis, cholestasis; hepatic failure requiring transplant has been reported.

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: Photosensitivity, rash, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Rifampin/Rifabutin

Concomitant administration of rifampin or rifabutin is known to reduce atovaquone concentrations [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. The concomitant administration of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets and rifampin or rifabutin is not recommended.

7.2 Anticoagulants

Proguanil may potentiate the anticoagulant effect of warfarin and other coumarin-based anticoagulants. The mechanism of this potential drug interaction has not been established. Caution is advised when initiating or withdrawing malaria prophylaxis or treatment with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets in patients on continuous treatment with coumarin-based anticoagulants. When these products are administered concomitantly, coagulation tests should be closely monitored.

7.3 Tetracycline

Concomitant treatment with tetracycline has been associated with a reduction in plasma concentrations of atovaquone [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Parasitemia should be closely monitored in patients receiving tetracycline.

7.4 Metoclopramide

While antiemetics may be indicated for patients receiving Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets, metoclopramide may reduce the bioavailability of atovaquone and should be used only if other antiemetics are not available [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.5 Indinavir

Concomitant administration of atovaquone and indinavir did not result in any change in the steady‑state AUC and Cmax of indinavir but resulted in a decrease in the Ctrough of indinavir [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Caution should be exercised when prescribing atovaquone with indinavir due to the decrease in trough concentrations of indinavir.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C

Atovaquone: Atovaquone was not teratogenic and did not cause reproductive toxicity in rats at doses up to 1,000 mg/kg/day corresponding to maternal plasma concentrations up to 7.3 times the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC. In rabbits, atovaquone caused adverse fetal effects and maternal toxicity at a dose of 1,200 mg/kg/day corresponding to plasma concentrations that were approximately 1.3 times the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC. Adverse fetal effects in rabbits, including decreased fetal body lengths and increased early resorptions and post-implantation losses, were observed only in the presence of maternal toxicity.

In a pre- and post-natal study in rats, atovaquone did not produce adverse effects in offspring at doses up to 1,000 mg/kg/day corresponding to AUC exposures of approximately 7.3 times the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria.

Proguanil: A pre- and post-natal study in Sprague-Dawley rats revealed no adverse effects at doses up to 16 mg/kg/day of proguanil hydrochloride (up to 0.04-times the average human exposure based on AUC). Pre- and post-natal studies of proguanil in animals at exposures similar to or greater than those observed in humans have not been conducted.

Atovaquone and Proguanil: The combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was not teratogenic in pregnant rats at atovaquone:proguanil hydrochloride (50:20 mg/kg/day) corresponding to plasma concentrations up to 1.7 and 0.1 times, respectively, the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC. In pregnant rabbits, the combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was not teratogenic or embryotoxic to rabbit fetuses at atovaquone:proguanil hydrochloride (100:40 mg/kg/day) corresponding to plasma concentrations of approximately 0.3 and 0.5 times, respectively, the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC.

There are no adequate and well‑controlled studies of atovaquone and/or proguanil hydrochloride in pregnant women. Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Falciparum malaria carries a higher risk of morbidity and mortality in pregnant women than in the general population. Maternal death and fetal loss are both known complications of falciparum malaria in pregnancy. In pregnant women who must travel to malaria‑endemic areas, personal protection against mosquito bites should always be employed in addition to antimalarials. [See Patient Counseling Information (17).]

The proguanil component of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets acts by inhibiting the parasitic dihydrofolate reductase [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.1)]. However, there are no clinical data indicating that folate supplementation diminishes drug efficacy. For women of childbearing age receiving folate supplements to prevent neural tube birth defects, such supplements may be continued while taking Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether atovaquone is excreted into human milk. In a rat study, atovaquone concentrations in the milk were 30% of the concurrent atovaquone concentrations in the maternal plasma.

Proguanil is excreted into human milk in small quantities.

Caution should be exercised when Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets are administered to a nursing woman.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Prophylaxis of Malaria: Safety and effectiveness have not been established in pediatric patients who weigh less than 11 kg. The efficacy and safety of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride have been established for the prophylaxis of malaria in controlled trials involving pediatric patients weighing 11 kg or more [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

Treatment of Malaria: Safety and effectiveness have not been established in pediatric patients who weigh less than 5 kg. The efficacy and safety of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for the treatment of malaria have been established in controlled trials involving pediatric patients weighing 5 kg or more [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

8.5 Geriatric Use

Clinical trials of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 years and older to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, the higher systemic exposure to cycloguanil, and the greater frequency of concomitant disease or other drug therapy. [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3).]

8.6 Renal Impairment

Do not use Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets for malaria prophylaxis in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min). Use with caution for the treatment of malaria in patients with severe renal impairment, only if the benefits of the 3-day treatment regimen outweigh the potential risks associated with increased drug exposure. No dosage adjustments are needed in patients with mild (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min) or moderate (creatinine clearance 30 to 50 mL/min) renal impairment. [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3).]

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

There is no information on overdoses of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets substantially higher than the doses recommended for treatment.

There is no known antidote for atovaquone, and it is currently unknown if atovaquone is dialyzable. Overdoses up to 31,500 mg of atovaquone have been reported. In one such patient who also took an unspecified dose of dapsone, methemoglobinemia occurred. Rash has also been reported after overdose.

Overdoses of proguanil hydrochloride as large as 1,500 mg have been followed by complete recovery, and doses as high as 700 mg twice daily have been taken for over 2 weeks without serious toxicity. Adverse experiences occasionally associated with proguanil hydrochloride doses of 100 to 200 mg/day, such as epigastric discomfort and vomiting, would be likely to occur with overdose. There are also reports of reversible hair loss and scaling of the skin on the palms and/or soles, reversible aphthous ulceration, and hematologic side effects.

-

11 DESCRIPTION

Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets (adult strength), for oral administration, contain a fixed‑dose combination of the antimalarial agents atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride.

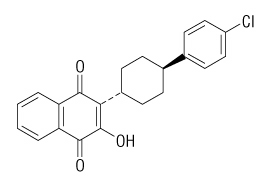

The chemical name of atovaquone is trans-2-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)cyclohexyl]-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthalenedione. Atovaquone is a yellow crystalline solid that is practically insoluble in water. It has a molecular weight of 366.84 and the molecular formula C22H19ClO3. The compound has the following structural formula:

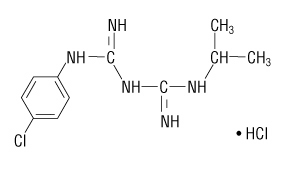

The chemical name of proguanil hydrochloride is 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-5-isopropyl-biguanide hydrochloride. Proguanil hydrochloride is a white crystalline solid that is sparingly soluble in water. It has a molecular weight of 290.22 and the molecular formula C11H16ClN5HCl. The compound has the following structural formula:

Each Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablet (adult strength) contains 250 mg of atovaquone and 100 mg of proguanil hydrochloride. The inactive ingredients are low-substituted hydroxypropyl cellulose, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, poloxamer 188, povidone K30, and sodium starch glycolate. The tablet coating contains hypromellose, polyethylene glycol 400, polyethylene glycol 8000, red iron oxide and titanium dioxide.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The constituents, atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride, interfere with 2 different pathways involved in the biosynthesis of pyrimidines required for nucleic acid replication. Atovaquone is a selective inhibitor of parasite mitochondrial electron transport. Proguanil hydrochloride primarily exerts its effect by means of the metabolite cycloguanil, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor. Inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase in the malaria parasite disrupts deoxythymidylate synthesis.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

No trials of the pharmacodynamics of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride have been conducted.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Absorption: Atovaquone is a highly lipophilic compound with low aqueous solubility. The bioavailability of atovaquone shows considerable inter‑individual variability.

Dietary fat taken with atovaquone increases the rate and extent of absorption, increasing AUC 2 to 3 times and Cmax 5 times over fasting. The absolute bioavailability of the tablet formulation of atovaquone when taken with food is 23%. Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets should be taken with food or a milky drink.

Distribution: Atovaquone is highly protein bound (>99%) over the concentration range of 1 to 90 mcg/mL. A population pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated that the apparent volume of distribution of atovaquone (V/F) in adult and pediatric patients after oral administration is approximately 8.8 L/kg.

Proguanil is 75% protein bound. A population pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated that the apparent V/F of proguanil in adult and pediatric patients >15 years of age with body weights from 31 to 110 kg ranged from 1,617 to 2,502 L. In pediatric patients ≤15 years of age with body weights from 11 to 56 kg, the V/F of proguanil ranged from 462 to 966 L.

In human plasma, the binding of atovaquone and proguanil was unaffected by the presence of the other.

Metabolism: In a study where 14C-labeled atovaquone was administered to healthy volunteers, greater than 94% of the dose was recovered as unchanged atovaquone in the feces over 21 days. There was little or no excretion of atovaquone in the urine (less than 0.6%). There is indirect evidence that atovaquone may undergo limited metabolism; however, a specific metabolite has not been identified. Between 40% to 60% of proguanil is excreted by the kidneys. Proguanil is metabolized to cycloguanil (primarily via CYP2C19) and 4-chlorophenylbiguanide. The main routes of elimination are hepatic biotransformation and renal excretion.

Elimination: The elimination half-life of atovaquone is about 2 to 3 days in adult patients.

The elimination half-life of proguanil is 12 to 21 hours in both adult patients and pediatric patients, but may be longer in individuals who are slow metabolizers.

A population pharmacokinetic analysis in adult and pediatric patients showed that the apparent clearance (CL/F) of both atovaquone and proguanil are related to the body weight. The values CL/F for both atovaquone and proguanil in subjects with body weight ≥11 kg are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Apparent Clearance for Atovaquone and Proguanil in Patients as a Function of Body Weight

Body Weight

Atovaquone

Proguanil

N

CL/F (L/hr)

Mean ± SDa (range)

N

CL/F (L/hr)

Mean ± SDa (range)

11 - 20 kg

159

1.34 ± 0.63

(0.52 - 4.26)

146

29.5 ± 6.5

(10.3 - 48.3)

21 - 30 kg

117

1.87 ± 0.81

(0.52 - 5.38)

113

40.0 ± 7.5

(15.9 - 62.7)

31 - 40 kg

95

2.76 ± 2.07

(0.97 - 12.5)

91

49.5 ± 8.30

(25.8 - 71.5)

>40 kg

368

6.61 ± 3.92

(1.32 - 20.3)

282

67.9 ± 19.9

(14.0 - 145)

a SD = standard deviation.

The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone and proguanil in patients with body weight below 11 kg have not been adequately characterized.

Pediatrics: The pharmacokinetics of proguanil and cycloguanil are similar in adult patients and pediatric patients. However, the elimination half‑life of atovaquone is shorter in pediatric patients (1 to 2 days) than in adult patients (2 to 3 days). In clinical trials, plasma trough concentrations of atovaquone and proguanil in pediatric patients weighing 5 to 40 kg were within the range observed in adults after dosing by body weight.

Geriatrics: In a single‑dose study, the pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil were compared in 13 elderly subjects (age 65 to 79 years) to 13 younger subjects (age 30 to 45 years). In the elderly subjects, the extent of systemic exposure (AUC) of cycloguanil was increased (point estimate = 2.36, 90% CI = 1.70, 3.28). Tmax was longer in elderly subjects (median 8 hours) compared with younger subjects (median 4 hours) and average elimination half‑life was longer in elderly subjects (mean 14.9 hours) compared with younger subjects (mean 8.3 hours).

Renal Impairment: In patients with mild renal impairment (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min), oral clearance and/or AUC data for atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil are within the range of values observed in patients with normal renal function (creatinine clearance >80 mL/min). In patients with moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30 to 50 mL/min), mean oral clearance for proguanil was reduced by approximately 35% compared with patients with normal renal function (creatinine clearance >80 mL/min) and the oral clearance of atovaquone was comparable between patients with normal renal function and mild renal impairment. No data exist on the use of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride for long-term prophylaxis (over 2 months) in individuals with moderate renal failure. In patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min), atovaquone Cmax and AUC are reduced but the elimination half‑lives for proguanil and cycloguanil are prolonged, with corresponding increases in AUC, resulting in the potential of drug accumulation and toxicity with repeated dosing [see Contraindications (4.2)].

Hepatic Impairment: In a single‑dose study, the pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil were compared in 13 subjects with hepatic impairment (9 mild, 4 moderate, as indicated by the Child‑Pugh method) to 13 subjects with normal hepatic function. In subjects with mild or moderate hepatic impairment as compared to healthy subjects, there were no marked differences (<50%) in the rate or extent of systemic exposure of atovaquone. However, in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment, the elimination half‑life of atovaquone was increased (point estimate = 1.28, 90% CI = 1.00 to 1.63). Proguanil AUC, Cmax, and its elimination half-life increased in subjects with mild hepatic impairment when compared to healthy subjects (Table 3). Also, the proguanil AUC and its elimination half-life increased in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment when compared to healthy subjects. Consistent with the increase in proguanil AUC, there were marked decreases in the systemic exposure of cycloguanil (Cmax and AUC) and an increase in its elimination half‑life in subjects with mild hepatic impairment when compared to healthy volunteers (Table 3). There were few measurable cycloguanil concentrations in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment. The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil after administration of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride have not been studied in patients with severe hepatic impairment.

Table 3. Point Estimates (90% CI) for Proguanil and Cycloguanil Parameters in Subjects With Mild and Moderate Hepatic Impairment Compared to Healthy Volunteers

Parameter

Comparison

Proguanil

Cycloguanil

AUC(0-inf)a

mild:healthy

1.96 (1.51, 2.54)

0.32 (0.22, 0.45)

Cmaxa

mild:healthy

1.41 (1.16, 1.71)

0.35 (0.24, 0.50)

t1/2b

mild:healthy

1.21 (0.92, 1.60)

0.86 (0.49, 1.48)

AUC(0-inf)a

moderate:healthy

1.64 (1.14, 2.34)

ND

Cmaxa

moderate:healthy

0.97 (0.69, 1.36)

ND

t1/2b

moderate:healthy

1.46 (1.05, 2.05)

ND

ND = not determined due to lack of quantifiable data.

a Ratio of geometric means.

b Mean difference.

Drug Interactions: There are no pharmacokinetic interactions between atovaquone and proguanil at the recommended dose.

Atovaquone is highly protein bound (>99%) but does not displace other highly protein-bound drugs in vitro.

Proguanil is metabolized primarily by CYP2C19. Potential pharmacokinetic interactions between proguanil or cycloguanil and other drugs that are CYP2C19 substrates or inhibitors are unknown.

Rifampin/Rifabutin: Concomitant administration of rifampin or rifabutin is known to reduce atovaquone concentrations by approximately 50% and 34%, respectively. The mechanisms of these interactions are unknown.

Tetracycline: Concomitant treatment with tetracycline has been associated with approximately a 40% reduction in plasma concentrations of atovaquone.

Metoclopramide: Concomitant treatment with metoclopramide has been associated with decreased bioavailability of atovaquone.

Indinavir: Concomitant administration of atovaquone (750 mg twice-daily with food for 14 days) and indinavir (800 mg three times daily without food for 14 days) did not result in any change in the steady‑state AUC and Cmax of indinavir but resulted in a decrease in the Ctrough of indinavir (23% decrease [90% CI = 8%, 35%]).

12.4 Microbiology

Activity In Vitro and In Vivo: Atovaquone and cycloguanil (an active metabolite of proguanil) are active against the erythrocytic and exoerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium spp. Enhanced efficacy of the combination compared to either atovaquone or proguanil hydrochloride alone was demonstrated in clinical trials in both immune and non-immune patients [see Clinical Studies (14.1, 14.2)].

Drug Resistance: Strains of P. falciparum with decreased susceptibility to atovaquone or proguanil/cycloguanil alone can be selected in vitro or in vivo. The combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride may not be effective for treatment of recrudescent malaria that develops after prior therapy with the combination.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Genotoxicity studies have not been performed with atovaquone in combination with proguanil. Effects of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride on male and female reproductive performance are unknown.

Atovaquone: A 24-month carcinogenicity study in CD rats was negative for neoplasms at doses up to 500 mg/kg/day corresponding to approximately 54 times the average steady-state plasma concentrations in humans during prophylaxis of malaria. In CD-1 mice, a 24‑month study showed treatment‑related increases in incidence of hepatocellular adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma at all doses tested (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg/day) which correlated with at least 15 times the average steady‑state plasma concentrations in humans during prophylaxis of malaria.

Atovaquone was negative with or without metabolic activation in the Ames Salmonella mutagenicity assay, the Mouse Lymphoma mutagenesis assay, and the Cultured Human Lymphocyte cytogenetic assay. No evidence of genotoxicity was observed in the in vivo Mouse Micronucleus assay.

Atovaquone did not impair fertility in male and female rats at doses up to 1,000 mg/kg/day corresponding to plasma exposures of approximately 7.3 times the estimated human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC.

Proguanil: No evidence of a carcinogenic effect was observed in 24-month studies conducted in CD-1 mice at doses up to 16 mg/kg/day corresponding to 1.5 times the average human plasma exposure during prophylaxis of malaria based on AUC, and in Wistar Hannover rats at doses up to 20 mg/kg/day corresponding to 1.1 times the average human plasma exposure during prophylaxis of malaria based on AUC.

Proguanil was negative with or without metabolic activation in the Ames Salmonella mutagenicity assay and the Mouse Lymphoma mutagenesis assay. No evidence of genotoxicity was observed in the in vivo Mouse Micronucleus assay.

Cycloguanil, the active metabolite of proguanil, was also negative in the Ames test, but was positive in the Mouse Lymphoma assay and the Mouse Micronucleus assay. These positive effects with cycloguanil, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, were significantly reduced or abolished with folinic acid supplementation.

A fertility study in Sprague-Dawley rats revealed no adverse effects at doses up to 16 mg/kg/day of proguanil hydrochloride (up to 0.04-times the average human exposure during treatment of malaria based on AUC). Fertility studies of proguanil in animals at exposures similar to or greater than those observed in humans have not been conducted.

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

Fibrovascular proliferation in the right atrium, pyelonephritis, bone marrow hypocellularity, lymphoid atrophy, and gastritis/enteritis were observed in dogs treated with proguanil hydrochloride for 6 months at a dose of 12 mg/kg/day (approximately 3.9 times the recommended daily human dose for malaria prophylaxis on a mg/m2 basis). Bile duct hyperplasia, gall bladder mucosal atrophy, and interstitial pneumonia were observed in dogs treated with proguanil hydrochloride for 6 months at a dose of 4 mg/kg/day (approximately 1.3 times the recommended daily human dose for malaria prophylaxis on a mg/m2 basis). Mucosal hyperplasia of the cecum and renal tubular basophilia were observed in rats treated with proguanil hydrochloride for 6 months at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day (approximately 1.6 times the recommended daily human dose for malaria prophylaxis on a mg/m2 basis). Adverse heart, lung, liver, and gall bladder effects observed in dogs and kidney effects observed in rats were not shown to be reversible.

-

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Prevention of P. falciparum Malaria

Atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was evaluated for prophylaxis of P. falciparum malaria in 5 clinical trials in malaria-endemic areas and in 3 active-controlled trials in non‑immune travelers to malaria-endemic areas.

Three placebo-controlled trials of 10 to 12 weeks’ duration were conducted among residents of malaria-endemic areas in Kenya, Zambia, and Gabon. The mean age of subjects was 30 (range 17‑55), 32 (range 16‑64), and 10 (range 5‑16) years, respectively. Of a total of 669 randomized patients (including 264 pediatric patients 5 to 16 years of age), 103 were withdrawn for reasons other than falciparum malaria or drug‑related adverse events (55% of these were lost to follow-up and 45% were withdrawn for protocol violations). The results are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Prevention of Parasitemiaa in Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride for Prophylaxis of P. falciparum Malaria in Residents of Malaria-Endemic Areas

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl

Placebo

Total number of patients randomized

326

343

Failed to complete study

57

46

Developed parasitemia (P. falciparum)

2

92

a Free of parasitemia during the 10 to 12-week period of prophylactic therapy.

In another study, 330 Gabonese pediatric patients (weighing 13 to 40 kg, and aged 4 to 14 years) who had received successful open‑label radical cure treatment with artesunate, were randomized to receive either atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (dosage based on body weight) or placebo in a double‑blind fashion for 12 weeks. Blood smears were obtained weekly and any time malaria was suspected. Nineteen of the 165 children given atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride and 18 of 165 patients given placebo withdrew from the study for reasons other than parasitemia (primary reason was lost to follow-up). One out of 150 evaluable patients (<1%) who received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride developed P. falciparum parasitemia while receiving prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride compared with 31 (22%) of the 144 evaluable placebo recipients.

In a 10‑week study in 175 South African subjects who moved into malaria‑endemic areas and were given prophylaxis with 1 Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablet daily, parasitemia developed in 1 subject who missed several doses of medication. Since no placebo control was included, the incidence of malaria in this study was not known.

Two active-controlled trials were conducted in non‑immune travelers who visited a malaria‑endemic area. The mean duration of travel was 18 days (range 2 to 38 days). Of a total of 1,998 randomized patients who received atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride or controlled drug, 24 discontinued from the study before follow-up evaluation 60 days after leaving the endemic area. Nine of these were lost to follow-up, 2 withdrew because of an adverse experience, and 13 were discontinued for other reasons. These trials were not large enough to allow for statements of comparative efficacy. In addition, the true exposure rate to P. falciparum malaria in both trials is unknown. The results are listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Prevention of Parasitemiaa in Active-Controlled Clinical Trials of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride for Prophylaxis of P. falciparum Malaria in Non-Immune Travelers

Atovaquone and Proguanil HCl

Mefloquine

Chloroquine plus Proguanil

Total number of randomized patients who received study drug

1,004

483

511

Failed to complete study

14

6

4

Developed parasitemia (P. falciparum)

0

0

3

a Free of parasitemia during the period of prophylactic therapy.

A third randomized, open‑label study was conducted which included 221 otherwise healthy pediatric patients (weighing ≥11 kg and 2 to 17 years of age) who were at risk of contracting malaria by traveling to an endemic area. The mean duration of travel was 15 days (range 1 to 30 days). Prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (n = 110, dosage based on body weight) began 1 or 2 days before entering the endemic area and lasted until 7 days after leaving the area. A control group (n = 111) received prophylaxis with chloroquine/proguanil dosed according to WHO guidelines. No cases of malaria occurred in either group of children. However, the study was not large enough to allow for statements of comparative efficacy. In addition, the true exposure rate to P. falciparum malaria in this study is unknown.

Causal Prophylaxis: In separate trials with small numbers of volunteers, atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride were independently shown to have causal prophylactic activity directed against liver‑stage parasites of P. falciparum. Six patients given a single dose of atovaquone 250 mg 24 hours prior to malaria challenge were protected from developing malaria, whereas all 4 placebo‑treated patients developed malaria.

During the 4 weeks following cessation of prophylaxis in clinical trial participants who remained in malaria‑endemic areas and were available for evaluation, malaria developed in 24 of 211 (11.4%) subjects who took placebo and 9 of 328 (2.7%) who took atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride. While new infections could not be distinguished from recrudescent infections, all but 1 of the infections in patients treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride occurred more than 15 days after stopping therapy. The single case occurring on day 8 following cessation of therapy with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride probably represents a failure of prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride.

The possibility that delayed cases of P. falciparum malaria may occur some time after stopping prophylaxis with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride cannot be ruled out. Hence, returning travelers developing febrile illnesses should be investigated for malaria.

14.2 Treatment of Acute, Uncomplicated P. falciparum Malaria Infections

In 3 phase II clinical trials, atovaquone alone, proguanil hydrochloride alone, and the combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride were evaluated for the treatment of acute, uncomplicated malaria caused by P. falciparum. Among 156 evaluable patients, the parasitological cure rate (elimination of parasitemia with no recurrent parasitemia during follow‑up for 28 days) was 59/89 (66%) with atovaquone alone, 1/17 (6%) with proguanil hydrochloride alone, and 50/50 (100%) with the combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride.

Atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was evaluated for treatment of acute, uncomplicated malaria caused by P. falciparum in 8 phase III randomized, open-label, controlled clinical trials (N = 1,030 enrolled in both treatment groups). The mean age of subjects was 27 years and 16% were children ≤12 years of age; 74% of subjects were male. Evaluable patients included those whose outcome at 28 days was known. Among 471 evaluable patients treated with the equivalent of 4 Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets once daily for 3 days, 464 had a sensitive response (elimination of parasitemia with no recurrent parasitemia during follow‑up for 28 days) (Table 6). Seven patients had a response of RI resistance (elimination of parasitemia but with recurrent parasitemia between 7 and 28 days after starting treatment). In these trials, the response to treatment with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was similar to treatment with the comparator drug in 4 trials.

Table 6. Parasitological Response in 8 Clinical Trials of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride for Treatment of P. falciparum Malaria

Study Site

Atovaquone and

Proguanil HCla

Comparator

Evaluable Patients

(n)

% Sensitive

Responseb

Drug(s)

Evaluable Patients

(n)

% Sensitive Responseb

Brazil

74

98.6%

Quinine and tetracycline

76

100.0%

Thailand

79

100.0%

Mefloquine

79

86.1%

Francec

21

100.0%

Halofantrine

18

100.0%

Kenyac,d

81

93.8%

Halofantrine

83

90.4%

Zambia

80

100.0%

Pyrimethamine/

sulfadoxine (P/S)

80

98.8%

Gabonc

63

98.4%

Amodiaquine

63

81.0%

Philippines

54

100.0%

Chloroquine (Cq)

Cq and P/S

23

32

30.4%

87.5%

Peru

19

100.0%

Chloroquine

P/S

13

7

7.7%

100.0%

a Atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride = 1,000 mg atovaquone and 400 mg proguanil hydrochloride (or equivalent based on body weight for patients weighing ≤40 kg) once daily for 3 days.

b Elimination of parasitemia with no recurrent parasitemia during follow‑up for 28 days.

c Patients hospitalized only for acute care. Follow‑up conducted in outpatients.

d Study in pediatric patients 3 to 12 years of age.

When these 8 trials were pooled and 2 additional trials evaluating atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride alone (without a comparator arm) were added to the analysis, the overall efficacy (elimination of parasitemia with no recurrent parasitemia during follow‑up for 28 days) in 521 evaluable patients was 98.7%.

The efficacy of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride in the treatment of the erythrocytic phase of nonfalciparum malaria was assessed in a small number of patients. Of the 23 patients in Thailand infected with P. vivax and treated with atovaquone/proguanil hydrochloride 1,000 mg/400 mg daily for 3 days, parasitemia cleared in 21 (91.3%) at 7 days. Parasite relapse occurred commonly when P. vivax malaria was treated with atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride alone. Relapsing malarias including P. vivax and P. ovale require additional treatment to prevent relapse.

The efficacy of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride in treating acute uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in children weighing ≥5 and <11 kg was examined in an open‑label, randomized trial conducted in Gabon. Patients received either 2 or 3 Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Pediatric Tablets (62.5 mg atovaquone and 25 mg proguanil hydrochloride) once daily depending upon body weight for 3 days (n = 100) or amodiaquine (10 mg/kg/day) for 3 days (n = 100). In this study, the Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Pediatric Tablets were crushed and mixed with condensed milk just prior to administration. An adequate clinical response (elimination of parasitemia with no recurrent parasitemia during follow‑up for 28 days) was obtained in 95% (87/92) of the evaluable pediatric patients who received Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Pediatric Tablets and in 53% (41/78) of those evaluable who received amodiaquine. A response of RI resistance (elimination of parasitemia but with recurrent parasitemia between 7 and 28 days after starting treatment) was noted in 3% and 40% of the patients, respectively. Two cases of RIII resistance (rising parasite count despite therapy) were reported in the patients receiving Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Pediatric Tablets. There were 4 cases of RIII in the amodiaquine arm.

- 16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

-

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Patients should be instructed:

- to take Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets at the same time each day with food or a milky drink.

- to take a repeat dose of Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets if vomiting occurs within 1 hour after dosing.

- to take a dose as soon as possible if a dose is missed, then return to their normal dosing schedule. However, if a dose is skipped, the patient should not double the next dose.

- that rare serious adverse events such as hepatitis, severe skin reactions, neurological, and hematological events have been reported when atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride was used for the prophylaxis or treatment of malaria.

- to consult a healthcare professional regarding alternative forms of prophylaxis if prophylaxis with Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride Tablets is prematurely discontinued for any reason.

- that protective clothing, insect repellents, and bednets are important components of malaria prophylaxis.

- that no chemoprophylactic regimen is 100% effective; therefore, patients should seek medical attention for any febrile illness that occurs during or after return from a malaria‑endemic area and inform their healthcare professional that they may have been exposed to malaria.

- that falciparum malaria carries a higher risk of death and serious complications in pregnant women than in the general population. Pregnant women anticipating travel to malarious areas should discuss the risks and benefits of such travel with their physicians.

Manufactured by:

GlaxoSmithKline

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

Manufactured for:

Prasco Laboratories

Mason, OH 45040 USA

APH-PS:2PI

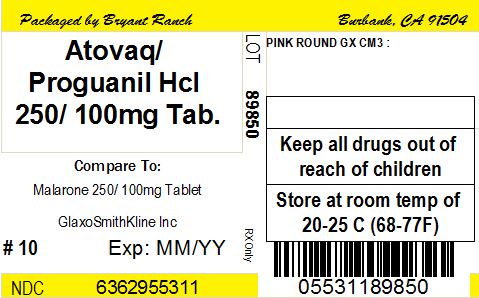

- Atovaq/ Proguanil Hcl 250/ 100mg Tab.

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ATOVAQUONE AND PROGUANIL HCL

atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride tablet, film coatedProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 63629-5531(NDC:66993-060) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ATOVAQUONE (UNII: Y883P1Z2LT) (ATOVAQUONE - UNII:Y883P1Z2LT) ATOVAQUONE 250 mg PROGUANIL HYDROCHLORIDE (UNII: R71Y86M0WT) (PROGUANIL - UNII:S61K3P7B2V) PROGUANIL HYDROCHLORIDE 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength LOW-SUBSTITUTED HYDROXYPROPYL CELLULOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 2165RE0K14) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) MICROCRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLOXAMER 188 (UNII: LQA7B6G8JG) POVIDONE K30 (UNII: U725QWY32X) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL 400 (UNII: B697894SGQ) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL 8000 (UNII: Q662QK8M3B) FERRIC OXIDE RED (UNII: 1K09F3G675) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color PINK Score no score Shape ROUND Size 11mm Flavor Imprint Code GX;CM3 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 63629-5531-1 10 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 01/21/2015 2 NDC: 63629-5531-2 24 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 01/21/2015 3 NDC: 63629-5531-3 5 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 01/21/2015 4 NDC: 63629-5531-4 12 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 11/15/2013 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA authorized generic NDA021078 07/27/2012 Labeler - Bryant Ranch Prepack (171714327) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Bryant Ranch Prepack 171714327 REPACK(63629-5531) , RELABEL(63629-5531)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.