Trimethoprim by Bryant Ranch Prepack TRIMETHOPRIM tablet

Trimethoprim by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Trimethoprim by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Bryant Ranch Prepack. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

DESCRIPTION

Trimethoprim is a synthetic antibacterial available in tablet form for oral administration. Each scored white tablet contains 100 mg trimethoprim.

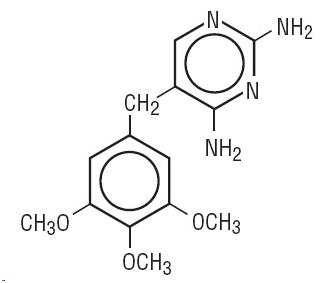

Trimethoprim is 5-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)methyl]-2,4-pyrimidinediamine. It is a white to light yellow, odorless, bitter compound with a molecular weight of 290.32 and the molecular formula C14H18N4O3. The structural formula is:

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Trimethoprim is rapidly absorbed following oral administration. It exists in the blood as unbound, protein-bound, and metabolized forms. Ten to twenty percent of trimethoprim is metabolized, primarily in the liver; the remainder is excreted unchanged in the urine. The principal metabolites of trimethoprim are the 1- and 3-oxides and the 3'- and 4'-hydroxy derivatives. The free form is considered to be the therapeutically active form. Approximately 44% of trimethoprim is bound to plasma proteins.

Mean peak serum concentrations of approximately 1.0 mcg/mL occur 1 to 4 hours after oral administration of a single 100 mg dose. A single 200 mg dose will result in serum levels approximately twice as high. The half-life of trimethoprim ranges from 8 to 10 hours. However, patients with severely impaired renal function exhibit an increase in the half-life of trimethoprim, which requires either dosage regimen adjustment or not using the drug in such patients (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). During a 13 week study of trimethoprim administered at a daily dosage of 200 mg (50 mg q.i.d.), the mean minimum steady-state concentration of the drug was 1.1 mcg/mL.

Steady-state concentrations were achieved within 2 to 3 days of chronic administration and were maintained throughout the experimental period.

Excretion of trimethoprim is primarily by the kidneys through glomerular filtration and tubular secretion. Urine concentrations of trimethoprim are considerably higher than are the concentrations in the blood. After a single oral dose of 100 mg, urine concentrations of trimethoprim ranged from 30 to 160 mcg/mL during the 0 to 4 hour period and declined to approximately 18 to 91 mcg/mL during the 8 to 24 hour period. A 200 mg single oral dose will result in trimethoprim urine levels approximately twice as high. After oral administration, 50% to 60% of trimethoprim is excreted in the urine within 24 hours, approximately 80% of this being unmetabolized trimethoprim.

Since normal vaginal and fecal flora are the source of most pathogens causing urinary tract infections, it is relevant to consider the distribution of trimethoprim into these sites. Concentrations of trimethoprim in vaginal secretions are consistently greater than those found simultaneously in the serum, being typically 1.6 times the concentrations of simultaneously obtained serum samples. Sufficient trimethoprim is excreted in the feces to markedly reduce or eliminate trimethoprim-susceptible organisms from the fecal flora.

Trimethoprim also passes the placental barrier and is excreted in human milk.

Microbiology

Mechanism of Action

Trimethoprim blocks the production of tetrahydrofolic acid from dihydrofolic acid by binding to and reversibly inhibiting the required enzyme, dihydrofolate reductase. This binding is very much stronger for the bacterial enzyme than for the corresponding mammalian enzyme. Thus, trimethoprim selectively interferes with bacterial biosynthesis of nucleic acids and proteins.

Resistance

Resistance to trimethoprim may be conferred by a variety of mechanisms including cell wall impermeability, overproduction of the chromosomal dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme, production of a resistant chromosomal DHFR enzyme or production of a plasmid-mediated trimethoprim-resistant DHFR enzyme. Acinetobacter baumannii/Acinetobacter calcoaceticus complex, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia are intrinsically resistant to trimethoprim. Non-Enterobacteriaceae fecal organisms, Bacteroides spp. and Lactobacillus spp. are not susceptible to trimethoprim at the concentrations obtained with the recommended dosage. Enterococcus spp, (E. faecalis, E. faecium, E. gallinarum/E. casseliflavus) may appear active in vitro to trimethoprim but are not effective clinically and should not be reported as susceptible. Moraxella catarrhalis isolates were found consistently resistant to trimethoprim.

Antimicrobial Activity

Trimethoprim has been shown to be active against most strains of the following microorganisms, both in vitro and in clinical infections as described in the INDICATIONS AND USAGE section.

Aerobic gram-positive bacteria

Staphylococcus species (coagulase-negative strains, including S. saprophyticus)

Aerobic gram-negative bacteria

Enterobacter species

Escherichia coli

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Proteus mirabilis

Susceptibility Test Methods

When available, the clinical microbiology laboratory should provide cumulative reports of in vitro susceptibility test results for antimicrobial drugs used in local hospitals and practice areas to the physician as periodic reports that describe the susceptibility profile of nosocomial and community-acquired pathogens. These reports should aid the physician in selecting an antibacterial drug for treatment.

Dilution techniques

Quantitative methods are used to determine antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC's). These MIC's provide estimates of the susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial compounds. The MIC's should be determined using a standardized procedure (broth and/or agar)1,7. The MIC values should be interpreted according to the criteria provided in Table 1.

Diffusion techniques

Quantitative methods that require measurement of zone diameters can also provide reproducible estimates of the susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial compounds. The zone size should be determined using a standardized test method.2,7 This procedure uses paper disks impregnated with 5 mcg trimethoprim to test the susceptibility of bacteria to trimethoprim. The disc diffusion breakpoints are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Susceptibility Test Interpretive Criteria for Trimethoprim

Pathogen

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations

(mcg)

Zone Diameters (mm)

S

I

R

S

I

R

Enterobacteriaceae

≤ 8

-

≥ 16

≥ 16

11-15

≤ 10

Coagulase negative staphylococci

(including S. saprophyticus )

≤ 8

-

≥ 16

≥ 16

11-15

≤ 10

A report of Susceptible (S) indicates that the antimicrobial drug is likely to inhibit growth of the pathogen if the antimicrobial drug reaches the concentration usually achievable at the site of infection. A report of Intermediate (I) indicates that the result should be considered equivocal, and, if the microorganism is not fully susceptible to alternative, clinically feasible drugs, the test should be repeated. This category implies possible clinical applicability in body sites where the drug is physiologically concentrated or in situations where a high dosage of the drug can be used. This category also provides a buffer zone that prevents small uncontrolled technical factors from causing major discrepancies in interpretation. A report of Resistant (R) indicates that the antimicrobial drug is not likely to inhibit growth of the pathogen if the antimicrobial drug reaches the concentration usually achievable at the infection site; other therapy should be selected.

Quality Control

Standardized susceptibility test procedures require the use of laboratory controls to monitor and ensure the accuracy and precision of supplies and reagents used in the assay, and the techniques of the individuals performing the test 1,2,7. Standard trimethoprim powder should provide the following range of MIC values noted in Table 2. For the diffusion technique using the 5 mcg disk, the criteria in Table 2 should be achieved.

Table 2: Quality Control Parameters for Trimethoprim

QC Strain

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (mcg/mL)

Zone Diameters (mm)

Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212

0.12 - 0.5

--

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922

0.5 - 2

21 - 28

Haemophilus influenzae ATCC 49247

0.06 - 0.5

27 - 33

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213

1 - 4

--

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923

--

19 - 26

Streptococcus pneumoniae

ATCC 49619

1 - 4

--

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853

> 64

--

-

INDICATIONS & USAGE

To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of trimethoprim tablets, USP and other antibacterial drugs, trimethoprim tablets, USP should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria. When culture and susceptibility information are available, they should be considered in selecting or modifying antibacterial therapy. In the absence of such data, local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns may contribute to the empiric selection of therapy.

For the treatment of initial episodes of uncomplicated urinary tract infections due to susceptible strains of the following organisms: Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter species, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, including S. saprophyticus.

Cultures and susceptibility tests should be performed to determine the susceptibility of the bacteria to trimethoprim. Therapy may be initiated prior to obtaining the results of these tests.

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Serious hypersensitivity reactions have been reported rarely in patients on trimethoprim therapy. Trimethoprim has been reported rarely to interfere with hematopoiesis, especially when administered in large doses and/or for prolonged periods.

The presence of clinical signs such as sore throat, fever, pallor, or purpura may be early indications of serious blood disorders (see OVERDOSAGE, Chronic).

Complete blood counts should be obtained if any of these signs are noted in a patient receiving trimethoprim and the drug discontinued if a significant reduction in the count of any formed blood element is found.

Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been reported with use of nearly all antibacterial agents, including trimethoprim tablets, USP, and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis. Treatment with antibacterial agents alters the normal flora of the colon leading to overgrowth of C. difficile.

C. difficile produces toxins A and B which contribute to the development of CDAD. Hypertoxin producing strains of C. difficile cause increased morbidity and mortality, as these infections can be refractory to antimicrobial therapy and may require colectomy. CDAD must be considered in all patients who present with diarrhea following antibiotic use. Careful medical history is necessary since CDAD has been reported to occur over two months after the administration of antibacterial agents.

If CDAD is suspected or confirmed, ongoing antiobiotic use not directed against C. difficile may need to be discontinued. Appropriate fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation, antibiotic treatment of C. difficile, and surgical evaluation should be instituted as clinically indicated.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Prescribing trimethoprim tablets, USP in the absence of a proven or strongly suspected bacterial infection or a prophylactic indication is unlikely to provide benefit to the patient and increases the risk of the development of drug-resistant bacteria.

Trimethoprim should be given with caution to patients with possible folate deficiency. Folates may be administered concomitantly without interfering with the antibacterial action of trimethoprim. Trimethoprim should also be given with caution to patients with impaired renal or hepatic function (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Information for Patients

Patients should be counseled that antibacterial drugs including trimethoprim tablets, USP should only be used to treat bacterial infections. They do not treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold). When trimethoprim tablets, USP are prescribed to treat a bacterial infection, patients should be told that although it is common to feel better early in the course of therapy, the medication should be taken exactly as directed. Skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may (1) decrease the effectiveness of the immediate treatment and (2) increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable by trimethoprim tablets, USP or other antibacterial drugs in the future.

Diarrhea is a common problem caused by antibiotics which usually ends when the antibiotic is discontinued. Sometimes after starting treatment with antibiotics, patients can develop watery and bloody stools (with and without stomach cramps and fever) even as late as two or more months after having taken the last dose of the antibiotic. If this occurs, patients should contact their physician as soon as possible.

Drug Interactions

Trimethoprim may inhibit the hepatic metabolism of phenytoin. Trimethoprim, given at a common clinical dosage, increased the phenytoin half-life by 51% and decreased the phenytoin metabolic clearance rate by 30%. When administering these drugs concurrently, one should be alert for possible excessive phenytoin effect.

Drug/Laboratory Test Interactions

Trimethoprim can interfere with a serum methotrexate assay as determined by the Competitive Binding Protein Technique (CBPA) when a bacterial dihydrofolate reductase is used as the binding protein. No interference occurs, however, if methotrexate is measured by a radioimmunoassay (RIA).

The presence of trimethoprim may also interfere with the Jaffe alkaline picrate reaction assay for creatinine, resulting in overestimations of about 10% in the range of normal values.

Carcinogenesis & Mutagenesis & Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Long-term studies in animals to evaluate carcinogenic potential have not been conducted with trimethoprim.

Mutagenesis

Trimethoprim was demonstrated to be nonmutagenic in the Ames assay. In studies at two laboratories, no chromosomal damage was detected in cultured Chinese hamster ovary cells at concentrations approximately 500 times human plasma levels; at concentrations approximately 1000 times human plasma levels in these same cells, a low level of chromosomal damage was induced at one of the laboratories. No chromosomal abnormalities were observed in cultured human leukocytes at concentrations of trimethoprim up to 20 times human steady-state plasma levels. No chromosomal effects were detected in peripheral lymphocytes of human subjects receiving 320 mg of trimethoprim in combination with up to 1600 mg of sulfamethoxazole per day for as long as 112 weeks.

Impairment of Fertility

No adverse effects on fertility or general reproductive performance were observed in rats given trimethoprim in oral dosages as high as 70 mg/kg/day for males and 14 mg/kg/day for females.

Pregnancy

Teratogenic Effects

Pregnancy category C

Trimethoprim has been shown to be teratogenic in the rat when given in doses 40 times the human dose. In some rabbit studies, the overall increase in fetal loss (dead and resorbed and malformed conceptuses) was associated with doses six times the human therapeutic dose.

While there are no large, well-controlled studies on the use of trimethoprim in pregnant women, Brumfitt and Pursell,3 in a retrospective study, reported the outcome of 186 pregnancies during which the mother received either placebo or trimethoprim in combination with sulfamethoxazole. The incidence of congenital abnormalities was 4.5% (3 of 66) in those who received placebo and 3.3% (4 of 120) in those receiving trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. There were no abnormalities in the 10 children whose mothers received the drug during the first trimester. In a separate survey, Brumfitt and Pursell also found no congenital abnormalities in 35 children whose mothers had received trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole at the time of conception or shortly thereafter.

Because trimethoprim may interfere with folic acid metabolism, trimethoprim should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Nonteratogenic Effects

The oral administration of trimethoprim to rats at a dose of 70 mg/kg/day commencing with the last third of gestation and continuing through parturition and lactation caused no deleterious effects on gestation or pup growth and survival.

Nursing Mothers

Trimethoprim is excreted in human milk. Because trimethoprim may interfere with folic acid metabolism, caution should be exercised when trimethoprim is administered to a nursing woman.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients below the age of 2 months have not been established. The effectiveness of trimethoprim as a single agent has not been established in pediatric patients under 12 years of age.

Geriatric Use

Clinical studies of trimethoprim tablets did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience4,5has not identified differences in response between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

Case reports of hyperkalemia in elderly patients receiving trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have been published.6 Trimethoprim is known to be substantially excreted by the kidney, and the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, care should be taken in dose selection, and it may be useful to monitor potassium concentrations and to monitor renal function by calculating creatinine clearance.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The adverse effects encountered most often with trimethoprim were rash and pruritus.

Dermatologic

Rash, pruritus, and phototoxic skin eruptions. At the recommended dosage regimens of 100 mg b.i.d. or 200 mg q.d., each for 10 days, the incidence of rash is 2.9% to 6.7%. In clinical studies which employed high doses of trimethoprim, an elevated incidence of rash was noted. These rashes were maculopapular, morbilliform, pruritic, and generally mild to moderate, appearing 7 to 14 days after the initiation of therapy.

Hypersensitivity

Rare reports of exfoliative dermatitis, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell Syndrome), and anaphylaxis have been received.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Acute

Signs of acute overdosage with trimethoprim may appear following ingestion of 1 gram or more of the drug and include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headaches, mental depression, confusion, and bone marrow depression (see Chronic subsection).

Treatment consists of gastric lavage and general supportive measures. Acidification of the urine will increase renal elimination of trimethoprim. Peritoneal dialysis is not effective and hemodialysis only moderately effective in eliminating the drug.

Chronic

Use of trimethoprim at high doses and/or for extended periods of time may cause bone marrow depression manifested as thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and/or megaloblastic anemia. If signs of bone marrow depression occur, trimethoprim should be discontinued and the patient should be given leucovorin; 5 to 15 mg leucovorin daily has been recommended by some investigators.

-

DOSAGE & ADMINISTRATION

The usual oral adult dosage is 100 mg of trimethoprim every 12 hours or 200 mg of trimethoprim every 24 hours, each for 10 days. The use of trimethoprim in patients with a creatinine clearance of less than 15 mL/min is not recommended. For patients with a creatinine clearance of 15 to 30 mL/min, the dose should be 50 mg every 12 hours.

- HOW SUPPLIED

-

REFERENCES

1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard-Tenth Edition. CLSI document M07-A10 [2015], Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA.

2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard-Twelfth Edition. CLSI document M02 A12 [2015], Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA.

3. Brumfitt W, Pursell R. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of bacteriuria in women. J Infect Dis. 1973;128(suppl): S657-S663.

4. Lacey RW, Simpson MHC, Fawcett C, et al. Comparison of single-dose trimethoprim with a five- day course for the treatment of urinary tract infections in the elderly. Age and Ageing 10: 179 185, 1981.

5. Ewer TC, Bailey RR, Gilchrist NL, et al. Comparative study of norfloxacin and trimethoprim for the treatment of elderly patients with urinary tract infection. NZ Med J 101: 537-539, 1988.

6. Marinella MA. Trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia: An analysis of reported cases. Gerontology 45: 209-212, 1999.

7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-sixth Informational Supplement, CLSI document M100-S26 [2016], Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA.

Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S22, Vol. 32, No. 3, CLSI, Wayne, PA, January, 2012.

Manufactured By:

Novel Laboratories, Inc.

Somerset, NJ 08873

Manufactured for:

Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Baltimore, MD 21202

PI3300000204

Rev. 09/2017

- Trimethoprim 100mg Tablet

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

TRIMETHOPRIM

trimethoprim tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 63629-7731(NDC:43386-330) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength TRIMETHOPRIM (UNII: AN164J8Y0X) (TRIMETHOPRIM - UNII:AN164J8Y0X) TRIMETHOPRIM 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MICROCRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) STARCH, CORN (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) WATER (UNII: 059QF0KO0R) Product Characteristics Color WHITE Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND Size 10mm Flavor Imprint Code NL;330 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 63629-7731-1 30 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 07/06/2018 2 NDC: 63629-7731-2 10 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 07/06/2018 3 NDC: 63629-7731-3 45 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 07/06/2018 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA091437 06/24/2011 Labeler - Bryant Ranch Prepack (171714327) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Bryant Ranch Prepack 171714327 REPACK(63629-7731) , RELABEL(63629-7731)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.