isosorbide dinitrate- Isosorbide Dinitrate tablet

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Drug Details [pdf]

- N/A - Section Title Not Found In Database

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

DESCRIPTION

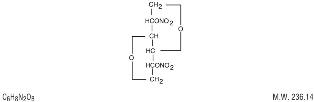

Isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) is 1,4:3,6-dianhydro-D-glucitol 2,5-dinitrate, an organic nitrate whose structural formula is:

The organic nitrates are vasodilators, active on both arteries and veins.

Isosorbide dinitrate is a white, crystalline, odorless compound which is stable in air and in solution, has a melting point of 70°C and has an optical rotation of +134° (c=1.0, alcohol, 20°C). Isosorbide dinitrate is freely soluble in organic solvents such as acetone, alcohol, and ether, but is only sparingly soluble in water.

Each isosorbide dinitrate tablet contains 30 mg of ISDN.

Inactive ingredients are as follows: Ammonium phosphate dibasic, colloidal silicon dioxide, FD&C Blue No. 1 Lake, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate and microcrystalline cellulose.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

The principal pharmacological action of ISDN is relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and consequent dilatation of peripheral arteries and veins, especially the latter. Dilatation of the veins promotes peripheral pooling of blood and decreases venous return to the heart, thereby reducing left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (preload). Arteriolar relaxation reduces systemic vascular resistance, systolic arterial pressure, and mean arterial pressure (afterload). Dilatation of the coronary arteries also occurs. The relative importance of preload reduction, afterload reduction, and coronary dilatation remains undefined.

Dosing regimens for most chronically used drugs are designed to provide plasma concentrations that are continuously greater than a minimally effective concentration. This strategy is inappropriate for organic nitrates. Several well-controlled clinical trials have used exercise testing to assess the anti-anginal efficacy of continuously-delivered nitrates. In the large majority of these trials, active agents were no more effective than placebo after 24 hours (or less) of continuous therapy. Attempts to overcome nitrate tolerance by dose escalation, even to doses far in excess of those used acutely, have consistently failed. Only after nitrates have been absent from the body for several hours has their anti-anginal efficacy been restored.

Pharmacokinetics: Absorption of ISDN after oral dosing is nearly complete, but bioavailability is highly variable (10% to 90%), with extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver. Serum levels reach their maxima about an hour after ingestion. The average bioavailability of ISDN is about 25%; most studies have observed progressive increases in bioavailability during chronic therapy.

Once absorbed, the volume of distribution of ISDN is 2 to 4 L/kg, and this volume is cleared at the rate of 2 to 4 L/min, so ISDN's half-life in serum is about an hour. Since the clearance exceeds hepatic blood flow, considerable extrahepatic metabolism must also occur. Clearance is affected primarily by denitration to the 2-mononitrate (15 to 25%) and the 5-mononitrate (75 to 85%).

Both metabolites have biological activity, especially the 5-mononitrate. With an overall half-life of about 5 hours, the 5-mononitrate is cleared from the serum by denitration to isosorbide, glucuronidation to the 5-mononitrate glucuronide, and denitration/hydration to sorbitol. The 2-mononitrate has been less well studied, but it appears to participate in the same metabolic pathways, with a half-life of about 2 hours.

The daily dose-free interval sufficient to avoid tolerance to organic nitrates has not been well defined. Studies of nitroglycerin (an organic nitrate with a very short half-life) have shown that daily dose-free intervals of 10 to 12 hours are usually sufficient to minimize tolerance. Daily dose-free intervals that have succeeded in avoiding tolerance during trials of moderate doses (e.g., 30 mg) of immediate-release ISDN have generally been somewhat longer (at least 14 hours), but this is consistent with the longer half-lives of ISDN and its active metabolites.

Few well-controlled clinical trials of organic nitrates have been designed to detect rebound or withdrawal effects. In one such trial, however, subjects receiving nitroglycerin had less exercise tolerance at the end of the daily dose-free interval than the parallel group receiving placebo. The incidence, magnitude, and clinical significance of similar phenomena in patients receiving ISDN have not been studied.

Clinical Trials: In clinical trials immediate-release oral ISDN has been administered in a variety of regimens, with total daily doses ranging from 30 mg to 480 mg. Controlled trials of single oral doses of ISDN have demonstrated effective reductions in exercise-related angina for up to 8 hours. Anti-anginal activity is present about 1 hour after dosing.

Most controlled trials of multiple-dose oral ISDN taken every 12 hours (or more frequently) for several weeks have shown statistically significant anti-anginal efficacy for only 2 hours after dosing. Once-daily regimens, and regimens with one daily dose-free interval of at least 14 hours (e.g., a regimen providing doses at 0800, 1400, and 1800 hours), have shown efficacy after the first dose of each day that was similar to that shown in the single-dose studies cited above. The effects of the second and later doses have been smaller and shorter-lasting than the effect of the first.

From large, well-controlled studies of other nitrates, it is reasonable to believe that the maximal achievable daily duration of anti-anginal effect from ISDN is about 12 hours. No dosing regimen for ISDN, however, has ever actually been shown to achieve this duration of effect. One study of 8 patients, who were administered a pretitrated dose (average 27.5 mg) of immediate-release ISDN at 0800, 1300, and 1800 hours for 2 weeks, revealed that significant anti-anginal effectiveness was discontinuous and totaled about 6 hours in a 24 hour period.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Amplification of the vasodilatory effects of ISDN by sildenafil can result in severe hypotension. The time course and dose dependence of this interaction have not been studied. Appropriate supportive care has not been studied, but it seems reasonable to treat this as a nitrate overdose, with elevation of the extremities and with central volume expansion.

The benefits of immediate-release oral ISDN in patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure have not been established. If one elects to use ISDN in these conditions, careful clinical or hemodynamic monitoring must be used to avoid the hazards of hypotension and tachycardia. Because the effects of oral ISDN are so difficult to terminate rapidly, this formulation is not recommended in these settings.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General: Severe hypotension, particularly with upright posture, may occur with even small doses of ISDN. This drug should therefore be used with caution in patients who may be volume depleted or who, for whatever reason, are already hypotensive. Hypotension induced by ISDN may be accompanied by paradoxical bradycardia and increased angina pectoris.

Nitrate therapy may aggravate the angina caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

As tolerance to ISDN develops, the effect of sublingual nitroglycerin on exercise tolerance, although still observable, is somewhat blunted.

Some clinical trials in angina patients have provided nitroglycerin for about 12 continuous hours of every 24-hour day. During the daily dose-free interval in some of these trials, anginal attacks have been more easily provoked than before treatment, and patients have demonstrated hemodynamic rebound and decreased exercise tolerance. The importance of these observations to the routine, clinical use of immediate-release oral ISDN is not known.

In industrial workers who have had long-term exposure to unknown (presumably high) doses of organic nitrates, tolerance clearly occurs. Chest pain, acute myocardial infarction, and even sudden death have occurred during temporary withdrawal of nitrates from these workers, demonstrating the existence of true physical dependence.

Information for Patients: Patients should be told that the anti-anginal efficacy of ISDN is strongly related to its dosing regimen, so the prescribed schedule of dosing should be followed carefully. In particular, daily headaches sometimes accompany treatment with ISDN. In patients who get these headaches, the headaches are a marker of the activity of the drug. Patients should resist the temptation to avoid headaches by altering the schedule of their treatment with ISDN, since loss of headache may be associated with simultaneous loss of anti-anginal efficacy. Aspirin and/or acetaminophen, on the other hand, often successfully relieve ISDN-induced headaches with no deleterious effect on ISDN'S anti-anginal efficacy.

Treatment with ISDN may be associated with lightheadedness on standing, especially just after rising from a recumbent or seated position. This effect may be more frequent in patients who have also consumed alcohol.

Drug Interactions: The vasodilating effects of ISDN may be additive with those of other vasodilators.

Alcohol, in particular, has been found to exhibit additive effects of this variety.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility: No long-term studies in animals have been performed to evaluate the carcinogenic potential of ISDN. In a modified two-litter reproduction study, there was no remarkable gross pathology and no altered fertility or gestation among rats fed ISDN at 25 or 100 mg/kg/day.

Pregnancy Category C: At oral doses 35 and 150 times the maximum recommended human daily dose, ISDN has been shown to cause a dose-related increase in embryotoxicity (increase in mummified pups) in rabbits. There are no adequate, well-controlled studies in pregnant women. ISDN should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Nursing Mothers: It is not known whether ISDN is excreted in human milk. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk, caution should be exercised when ISDN is administered to a nursing woman.

Geriatric Use: Clinical studies of ISDN did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Adverse reactions to ISDN are generally dose-related, and almost all of these reactions are the result of ISDN's activity as a vasodilator. Headache, which may be severe, is the most commonly reported side effect. Headache may be recurrent with each daily dose, especially at higher doses. Transient episodes of lightheadedness, occasionally related to blood pressure changes, may also occur. Hypotension occurs infrequently, but in some patients it may be severe enough to warrant discontinuation of therapy. Syncope, crescendo angina, and rebound hypertension have been reported but are uncommon.

Extremely rarely, ordinary doses of organic nitrates have caused methemoglobinemia in normal-seeming patients. Methemoglobinemia is so infrequent at these doses that further discussion of its diagnosis and treatment is deferred (see OVERDOSAGE).

Data are not available to allow estimation of the frequency of adverse reactions during treatment of isosorbide dinitrate tablets.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Hemodynamic Effects: The ill effects of ISDN overdose are generally the results of ISDN's capacity to induce vasodilatation, venous pooling, reduced cardiac output, and hypotension. These hemodynamic changes may have protean manifestations, including increased intracranial pressure, with any or all of persistent throbbing headache, confusion, and moderate fever; vertigo; palpitations; visual disturbances; nausea and vomiting (possibly with colic and even bloody diarrhea); syncope (especially in the upright posture); air hunger and dyspnea, later followed by reduced ventilatory effort; diaphoresis, with the skin either flushed or cold and clammy; heart block and bradycardia; paralysis; coma; seizures; and death.

Laboratory determinations of serum levels of ISDN and it metabolites are not widely available, and such determinations have, in any event, no established role in the management of ISDN overdose.

There are no data suggesting what dose of ISDN is likely to be life-threatening in humans. In rats, the median acute lethal dose (LD50) was found to be 1100 mg/kg.

No data are available to suggest physiological maneuvers (e.g., maneuvers to change the pH of the urine) that might accelerate elimination of ISDN and its active metabolites. Similarly, it is not known which, if any, of these substances can usefully be removed from the body by hemodialysis.

No specific antagonist to the vasodilator effects of ISDN is known, and no intervention has been subject to controlled studies as a therapy for ISDN overdose. Because the hypotension associated with ISDN overdose is the result of venodilatation and arterial hypovolemia, prudent therapy in this situation should be directed toward increase in central fluid volume. Passive elevation of the patient's legs may be sufficient, but intravenous infusion of normal saline or similar fluid may also be necessary.

The use of epinephrine or other arterial vasoconstrictors in this setting is likely to do more harm than good.

In patients with renal disease or congestive heart failure, therapy resulting in central volume expansion is not without hazard. Treatment of ISDN overdose in these patients may be subtle and difficult, and invasive monitoring may be required.

Methemoglobinemia: Nitrate ions liberated during metabolism of ISDN can oxidize hemoglobin into methemoglobin. Even in patients totally without cytochrome b5 reductase activity, however, and even assuming that the nitrate moieties of ISDN are quantitatively applied to oxidation of hemoglobin, about 1 mg/kg of ISDN should be required before any of these patients manifests clinically significant (≥10%) methemoglobinemia. In patients with normal reductase function, significant production of methemoglobin should require even larger doses of ISDN. In one study in which 36 patients received 2 to 4 weeks of continuous nitroglycerin therapy at 3.1 to 4.4 mg/hr (equivalent, in total administered dose of nitrate ions, to 4.8 to 6.9 mg of bioavailable ISDN per hour), the average methemoglobin level measured was 0.2%; this was comparable to that observed in parallel patients who received placebo.

Notwithstanding these observations, there are case reports of significant methemoglobinemia in association with moderate overdoses of organic nitrates. None of the affected patients had been thought to be unusually susceptible.

Methemoglobin levels are available from most clinical laboratories. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients who exhibit signs of impaired oxygen delivery despite adequate cardiac output and adequate arterial pO2. Classically, methemoglobinemic blood is described as chocolate brown, without color change on exposure to air.

When methemoglobinemia is diagnosed, the treatment of choice is methylene blue, 1 to 2 mg/kg intravenously.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

As noted under CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY multiple-dose studies with ISDN and other nitrates have shown that maintenance of continuous 24-hour plasma levels results in refractory tolerance. Every dosing regimen for isosorbide dinitrate tablets must provide a daily dose-free interval to minimize the development of this tolerance. With immediate-release ISDN, it appears that one daily dose-free interval must be at least 14 hours long.

As also noted under CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, the effects of the second and later doses have been smaller and shorter-lasting than the effects of the first.

Large controlled studies with other nitrates suggest that no dosing regimen with isosorbide dinitrate oral tablets should be expected to provide more than about 12 hours of continuous anti-anginal efficacy per day.

As with all titratable drugs, it is important to administer the minimum dose which produces the desired clinical effect. The usual starting dose of isosorbide dinitrate tablets is 5 mg to 40 mg, two or three times daily. For maintenance therapy, 10 mg to 40 mg, two or three times daily is recommended. Some patients may require higher doses. A daily dose-free interval of at least 14 hours is advisable to minimize tolerance. The optimal interval will vary with the individual patient, dose and regimen.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Isosorbide Dinitrate Tablets USP (Oral) 30 mg: Blue, round, scored tablets embossed “WW 773” on scored side..

- Bottles of 30 tablets.

- Bottles of 100 tablets.

- Bottles of 500 tablets.

- Bottles of 1000 tablets.

Store at 20-25°C (68-77°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Protect from light and moisture.

Dispense in a tight, light-resistant container as defined in the USP using a child-resistant closure.

Also available: Isosorbide Dinitrate Sublingual Tablets in the following dosage strengths:

2.5 mg; in bottles of 100, 1000 or unit dose boxes of 100 tablets.

5 mg; in bottles of 100, 1000 or unit dose boxes of 100 tablets.

Also available: Isosorbide Dinitrate Oral Tablets in the following dosage strengths:

5 mg: in bottles of 100, 500, 1000 or unit dose boxes of 100 tablets.

10 mg: in bottles of 100, 500, 1000 or unit dose boxes of 100 tablets.

20 mg: in bottles of 100, 1000 or unit dose boxes of 100 tablets.

Manufactured by:

West-ward Pharmaceutical Corp.

Eatontown, NJ 07724

Issued August 2004 -

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ISOSORBIDE DINITRATE

isosorbide dinitrate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0143-1773 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength Isosorbide Dinitrate (UNII: IA7306519N) (Isosorbide Dinitrate - UNII:IA7306519N) 30 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength Ammonium Phosphate dibasic () Colloidal Silicon Dioxide () FD&C Blue No. 1 lake () Lactose Monohydrate (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) Magnesium Stearate (UNII: 70097M6I30) Microcrystalline Cellulose () Product Characteristics Color blue (BLUE) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND (ROUND) Size 8mm Flavor Imprint Code WW;773 Contains Coating false Symbol false Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0143-1773-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC 2 NDC: 0143-1773-01 100 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC 3 NDC: 0143-1773-05 500 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC 4 NDC: 0143-1773-10 1000 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC Labeler - West-ward Pharmaceutical Corp.

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.