ENTACAPONE tablet, film coated

ENTACAPONE by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

ENTACAPONE by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Alembic Pharmaceuticals Inc., Alembic Pharmaceuticals Limited. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

Entacapone is available as tablets containing 200 mg entacapone, USP.

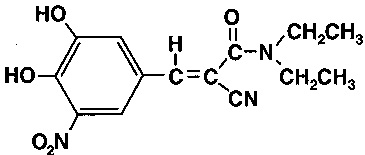

Entacapone is an inhibitor of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease as an adjunct to levodopa and carbidopa therapy. It is a nitrocatechol-structured compound with a relative molecular mass of 305.29. The chemical name of entacapone is (E)-2-cyano3-(3,4-dihydroxy-5-nitrophenyl)-N,N-diethyl-2-propenamide. Its empirical formula is C14H15N3O5 and its structural formula is:

The inactive ingredients of the entacapone tablets, USP are microcrystalline cellulose, mannitol, croscarmellose sodium, colloidal silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, hydrogenated vegetable oil, hypromellose, glycerin, titanium dioxide, iron oxide yellow, sucrose, polysorbate 80 and iron oxide red.

FDA approved dissolution testing specifications differ from USP.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

Entacapone is a selective and reversible inhibitor of COMT.

In mammals, COMT is distributed throughout various organs with the highest activities in the liver and kidney. COMT also occurs in the heart, lung, smooth and skeletal muscles, intestinal tract, reproductive organs, various glands, adipose tissue, skin, blood cells, and neuronal tissues, especially in glial cells. COMT catalyzes the transfer of the methyl group of S-adenosyl-L-methionine to the phenolic group of substrates that contain a catechol structure. Physiological substrates of COMT include dopa, catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine) and their hydroxylated metabolites. The function of COMT is the elimination of biologically active catechols and some other hydroxylated metabolites. In the presence of a decarboxylase inhibitor, COMT becomes the major metabolizing enzyme for levodopa, catalyzing the metabolism to 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy-L phenylalanine (3-OMD) in the brain and periphery.

The mechanism of action of entacapone is believed to be through its ability to inhibit COMT and alter the plasma pharmacokinetics of levodopa. When entacapone is given in conjunction with levodopa and an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor, such as carbidopa, plasma levels of levodopa are greater and more sustained than after administration of levodopa and an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor alone. It is believed that at a given frequency of levodopa administration, these more sustained plasma levels of levodopa result in more constant dopaminergic stimulation in the brain, leading to greater effects on the signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The higher levodopa levels also lead to increased levodopa adverse effects, sometimes requiring a decrease in the dose of levodopa.

In animals, while entacapone enters the central nervous system (CNS) to a minimal extent, it has been shown to inhibit central COMT activity. In humans, entacapone inhibits the COMT enzyme in peripheral tissues. The effects of entacapone on central COMT activity in humans have not been studied.

Pharmacodynamics

COMT Activity in Erythrocytes: Studies in healthy volunteers have shown that entacapone reversibly inhibits human erythrocyte COMT activity after oral administration. There was a linear correlation between entacapone dose and erythrocyte COMT inhibition, the maximum inhibition being 82% following an 800 mg single dose. With a 200 mg single dose of entacapone, maximum inhibition of erythrocyte COMT activity is on average 65% with a return to baseline level within 8 hours.

Effect on the Pharmacokinetics of Levodopa and its Metabolites

When 200 mg entacapone is administered together with levodopa and carbidopa, it increases the area under the curve (AUC) of levodopa by approximately 35% and the elimination half-life of levodopa is prolonged from 1.3 hours to 2.4 hours. In general, the average peak levodopa plasma concentration and the time of its occurrence (Tmax of 1 hour) are unaffected. The onset of effect occurs after the first administration and is maintained during long-term treatment. Studies in Parkinson’s disease patients suggest that the maximal effect occurs with 200 mg entacapone. Plasma levels of 3-OMD are markedly and dose-dependently decreased by entacapone when given with levodopa and carbidopa.

Pharmacokinetics of Entacapone

Entacapone pharmacokinetics are linear over the dose range of 5 mg to 800 mg, and are independent of levodopa and carbidopa coadministration. The elimination of entacapone is biphasic, with an elimination half-life of 0.4 hour to 0.7 hour based on the β-phase and 2.4 hours based on the γ-phase. The γ-phase accounts for approximately 10% of the total AUC. The total body clearance after intravenous administration is 850 mL per min. After a single 200 mg dose of entacapone, the Cmax is approximately 1.2 mcg per mL.Absorption: Entacapone is rapidly absorbed, with a Tmax of approximately 1 hour. The absolute bioavailability following oral administration is 35%. Food does not affect the pharmacokinetics of entacapone.

Distribution: The volume of distribution of entacapone at steady state after intravenous injection is small (20 L). Entacapone does not distribute widely into tissues due to its high plasma protein binding. Based on in vitro studies, the plasma protein binding of entacapone is 98% over the concentration range of 0.4 mcg per mL to 50 mcg per mL. Entacapone binds mainly to serum albumin.

Metabolism and Elimination: Entacapone is almost completely metabolized prior to excretion, with only a very small amount (0.2% of dose) found unchanged in urine. The main metabolic pathway is isomerization to the cis-isomer, followed by direct glucuronidation of the parent and cis-isomer; the glucuronide conjugate is inactive. After oral administration of a 14C-labeled dose of entacapone, 10% of labeled parent and metabolite is excreted in urine and 90% in feces.

Special Populations: Entacapone pharmacokinetics are independent of age. No formal gender studies have been conducted. Racial representation in clinical studies was largely limited to Caucasians; therefore, no conclusions can be reached about the effect of entacapone on groups other than Caucasian.

Hepatic Impairment: A single 200 mg dose of entacapone, without levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor coadministration, showed approximately 2-fold higher AUC and Cmax values in patients with a history of alcoholism and hepatic impairment (n=10) compared to normal subjects (n=10). All patients had biopsy-proven liver cirrhosis caused by alcohol. According to Child-Pugh grading seven patients with liver disease had mild hepatic impairment and three patients had moderate hepatic impairment. As only about 10% of the entacapone dose is excreted in urine as parent compound and conjugated glucuronide, biliary excretion appears to be the major route of excretion of this drug. Consequently, entacapone should be administered with care to patients with biliary obstruction.

Renal Impairment: The pharmacokinetics of entacapone have been investigated after a single 200 mg entacapone dose, without levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor coadministration, in a specific renal impairment study. There were three groups: normal subjects (n=7; creatinine clearance greater than 1.12 mL per sec per 1.73 m2), moderate impairment (n=10; creatinine clearance ranging from 0.60 mL per sec per 1.73 m2 to 0.89 mL per sec per 1.73 m2), and severe impairment (n=7; creatinine clearance ranging from 0.2 mL per sec per 1.73 m2 to 0.44 mL per sec per 1.73 m2). No important effects of renal function on the pharmacokinetics of entacapone were found.

Drug Interactions: See PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.

Clinical Studies

The effectiveness of entacapone as an adjunct to levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease was established in three 24-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients with Parkinson’s disease. In two of these studies, patients had motor “fluctuations”, characterized by documented periods of “On” (periods of relatively good functioning) and “Off” (periods of relatively poor functioning), despite optimum levodopa therapy. There was also a withdrawal period following 6 months of treatment. In the third study, patients were not required to have motor fluctuations. Prior to the controlled part of the studies, patients were stabilized on levodopa for 2 weeks to 4 weeks. Entacapone has not been systematically evaluated in patients who have Parkinson’s disease without motor fluctuations.In the first two studies to be described, patients were randomized to receive placebo or entacapone 200 mg administered concomitantly with each dose of levodopa and carbidopa (up to 10 times daily, but averaging 4 doses to 6 doses per day). The formal double-blind portion of both studies was 6 months long. Patients recorded the time spent in the “On” and “Off” states in home diaries periodically throughout the duration of the study. In one study, conducted in the Nordic countries, the primary outcome measure was the total mean time spent in the “On” state during an 18-hour diary recorded day (6 AM to midnight). In the other study, the primary outcome measure was the proportion of awake time spent over 24 hours in the “On” state.

In addition to the primary outcome measure: the amount of time spent in the “Off” state, subparts of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) including mentation (Part I), activities of daily living (ADL) (Part II), motor function (Part III), complications of therapy (Part IV), and disease staging (Part V and VI) were assessed. Additional secondary endpoints included the investigator’s and patient’s global assessment of clinical condition, a 7-point subjective scale designed to assess global functioning in Parkinson’s disease; and the change in daily levodopa and carbidopa dose.

In one of the studies, 171 patients were randomized in 16 centers in Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (Nordic study), all of whom received concomitant levodopa plus dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor (either levodopa and carbidopa or levodopa and benserazide). In the second study, 205 patients were randomized in 17 centers in North America (US and Canada); all patients received concomitant levodopa and carbidopa.

The following tables display the results of these two studies:

Table 1. Nordic Study

Primary Measure from Home Diary (from an 18-hour Diary Day)

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6*

p-value vs. placebo

Hours of Awake Time “On”

Placebo

9.2

+0.1

–

Entacapone

9.3

+1.5

less than 0.001

Duration of “On” time after first AM dose (hrs)

Placebo

2.2

0

–

Entacapone

2.1

+0.2

less than 0.05

Secondary Measures from Home Diary (from an 18-hour Diary Day) ‡‡

Hours of Awake Time “Off”

Placebo

5.3

0

–

Entacapone

5.5

-1.3

less than 0.001

Proportion of Awake Time “On” *** (%)

Placebo

63.8

+0.6

–

Entacapone

62.7

+9.3

less than 0.001

Levodopa Total Daily Dose (mg)

Placebo

705

+14

–

Entacapone

701

-87

less than 0.001

Frequency of Levodopa Daily Intakes

Placebo

6.1

+0.1

–

Entacapone

6.2

-0.4

less than 0.001

Other Secondary Measures‡‡

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6*

p-value vs. placebo

Investigator’s Global (overall) % Improved**

Placebo

–

28

–

Entacapone

–

56

less than 0.01

Patient’s Global (overall) % Improved**

Placebo

–

22

–

Entacapone

–

39

N.S.‡

UPDRS Total

Placebo

37.4

-1.1

–

Entacapone

38.5

-4.8

less than 0.01

UPDRS Motor

Placebo

24.6

-0.7

–

Entacapone

25.5

-3.3

less than 0.05

UPDRS ADL

Placebo

11

-0.4

–

Entacapone

11.2

-1.8

less than 0.05

* Mean; the month 6 values represent the average of weeks 8, 16, and 24, by protocol-defined outcome measure, except for Investigator’s and Patient’s Global Improvement.

** At least one category change at endpoint.

*** Not an endpoint for this study but primary endpoint in the North American Study.

‡ Not significant.

‡‡ P values for Secondary Measures and Other Secondary Measures are nominal P values without any adjustment for multiplicity.

Table 2. North American Study

Primary Measure from Home Diary (for a 24-hour Diary Day)

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6*

p-value vs. placebo

Percent of Awake Time “On”

Placebo

60.8

+2

–

Entacapone

60

+6.7

less than 0.05

Secondary Measures from Home Diary (for a 24-hour Diary Day) ‡‡

Hours of Awake Time “Off”

Placebo

6.6

-0.3

–

Entacapone

6.8

-1.2

less than 0.01

Hours of Awake Time “On”

Placebo

10.3

+0.4

–

Entacapone

10.2

+1

N.S.‡

Levodopa Total Daily Dose (mg)

Placebo

758

+19

–

Entacapone

804

-93

less than 0.001

Frequency of Levodopa Daily Intakes

Placebo

6

+0.2

–

Entacapone

6.2

0

N.S.‡

Other Secondary Measures‡‡

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6*

p-value vs. placebo

Investigator’s Global (overall) % Improved**

Placebo

–

21

–

Entacapone

–

34

less than 0.05

Patient’s Global (overall) % Improved**

Placebo

–

20

–

Entacapone

–

31

less than 0.05

UPDRS Total***

Placebo

35.6

+2.8

–

Entacapone

35.1

-0.6

less than 0.05

UPDRS Motor***

Placebo

22.6

+1.2

–

Entacapone

22

-0.9

less than 0.05

UPDRS ADL***

Placebo

11.7

+1.1

–

Entacapone

11.9

0

less than 0.05

* Mean; the month 6 values represent the average of weeks 8, 16, and 24, by protocol-defined outcome measure, except for Investigator’s and Patient’s Global Improvement.

** At least one category change at endpoint.

*** Score change at endpoint similarly to the Nordic Study.

‡ Not significant.

‡‡ P values for Secondary Measures and Other Secondary Measures are nominal P values without any adjustment for multiplicity.

Effects on “On” time did not differ by age, sex, weight, disease severity at baseline, levodopa dose and concurrent treatment with dopamine agonists or selegiline.

Withdrawal of entacapone: In the North American study, abrupt withdrawal of entacapone, without alteration of the dose of levodopa and carbidopa, resulted in a significant worsening of fluctuations, compared to placebo. In some cases, symptoms were slightly worse than at baseline, but returned to approximately baseline severity within two weeks following levodopa dose increase on average by 80 mg. In the Nordic study, similarly, a significant worsening of parkinsonian symptoms was observed after entacapone withdrawal, as assessed two weeks after drug withdrawal. At this phase, the symptoms were approximately at baseline severity following levodopa dose increase by about 50 mg.

In the third placebo-controlled study, a total of 301 patients were randomized in 32 centers in Germany and Austria. In this study, as in the other two studies, entacapone 200 mg was administered with each dose of levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (up to 10 times daily) and UPDRS Parts II and III and total daily “On” time were the primary measures of effectiveness. The following results were observed for the primary measures, as well as for some secondary measures:

Table 3. German-Austrian Study

Primary Measures

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6

p-value

vs. placebo

(LOCF)

UPDRS ADL*

Placebo

12

+0.5

–

Entacapone

12.4

-0.4

less than 0.05

UPDRS Motor*

Placebo

24.1

+0.1

–

Entacapone

24.9

-2.5

less than 0.05

Hours of Awake Time “On” (Home diary)**

Placebo

10.1

+0.5

–

Entacapone

10.2

+1.1

N.S.‡

Secondary Measures‡‡

Baseline

Change from Baseline at Month 6

p-value vs. placebo

UPDRS Total*

Placebo

37.7

+0.6

–

Entacapone

39

-3.4

less than 0.05

Percent of Awake Time “On” (Home diary)**

Placebo

59.8

+3.5

–

Entacapone

62

+6.5

N.S.‡

Hours of Awake Time “Off” (Home diary)**

Placebo

6.8

-0.6

–

Entacapone

6.3

-1.2

0.07

Levodopa Total Daily Dose (mg)*

Placebo

572

+4

–

Entacapone

566

-35

N.S.‡

Frequency of Levodopa Daily Intake*

Placebo

5.6

+0.2

–

Entacapone

5.4

0

less than 0.01

Global (overall) % Improved***

Placebo

–

34

–

Entacapone

–

38

N.S.‡

* Total population; score change at endpoint.

** Fluctuating population, with 5 doses to 10 doses; score change at endpoint.

*** Total population; at least one category change at endpoint.

‡ Not significant.

‡‡ P values for Secondary Measures are nominal P values without any adjustment for multiplicity.

-

INDICATIONS

Entacapone tablets are indicated as an adjunct to levodopa and carbidopa to treat end-of-dose “wearing-off” in patients with Parkinson’s disease (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Clinical Studies).

Entacapone tablets effectiveness has not been systematically evaluated in patients with Parkinson’s disease who do not experience end-of-dose “wearing-off”.

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) and COMT are the two major enzyme systems involved in the metabolism of catecholamines. It is theoretically possible, therefore, that the combination of entacapone and a non-selective MAO inhibitor (e.g., phenelzine and tranylcypromine) would result in inhibition of the majority of the pathways responsible for normal catecholamine metabolism. For this reason, patients should ordinarily not be treated concomitantly with entacapone and a non-selective MAO inhibitor.

Entacapone can be taken concomitantly with a selective MAO-B inhibitor (e.g., selegiline).

Drugs Metabolized By Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT)

When a single 400 mg dose of entacapone was given with intravenous isoprenaline (isoproterenol) and epinephrine without coadministered levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor, the overall mean maximal changes in heart rate during infusion were about 50% and 80% higher than with placebo, for isoprenaline and epinephrine, respectively.

Therefore, drugs known to be metabolized by COMT, such as isoproterenol, epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine, alpha-methyldopa, apomorphine, isoetherine, and bitolterol should be administered with caution in patients receiving entacapone regardless of the route of administration (including inhalation), as their interaction may result in increased heart rates, possible arrhythmias, and excessive changes in blood pressure.

Ventricular tachycardia was noted in one 32-year-old healthy male volunteer in an interaction study after epinephrine infusion and oral entacapone administration. Treatment with propranolol was required. A causal relationship to entacapone administration appears probable but cannot be attributed with certainty.

Falling Asleep During Activities of Daily Living and Somnolence

Patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with entacapone, which increases plasma levodopa levels, or with levodopa have reported suddenly falling asleep without prior warning of sleepiness while engaged in activities of daily living (including the operation of motor vehicles). Some of these episodes resulted in accidents. Although many of these patients reported somnolence while on entacapone, some did not perceive warning signs, such as excessive drowsiness, and believed that they were alert immediately prior to the event. Some of these events have been reported as late as one year after initiation of treatment.

The risk of somnolence was increased (entacapone 2% and placebo 0%) in controlled studies. It has been reported that falling asleep while engaged in activities of daily living always occurs in a setting of preexisting somnolence, although patients may not give such a history. For this reason, prescribers should reassess patients for drowsiness or sleepiness especially since some of the events occur well after the start of treatment. Prescribers should also be aware that patients may not acknowledge drowsiness or sleepiness until directly questioned about drowsiness or sleepiness during specific activities. Patients should be advised to exercise caution while driving, operating machines, or working at heights during treatment with entacapone. Patients who have already experienced somnolence and/or an episode of sudden sleep onset should not participate in these activities during treatment with entacapone.

Before initiating treatment with entacapone, advise patients of the potential to develop drowsiness and specifically ask about factors that may increase this risk such as concomitant use of sedating medications and the presence of sleep disorders. If a patient develops daytime sleepiness or episodes of falling asleep during activities that require active participation (e.g., conversations, eating, etc.), entacapone should ordinarily be discontinued (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION for guidance on discontinuing entacapone). If the decision is made to continue entacapone, patients should be advised not to drive and to avoid other potentially dangerous activities. There is insufficient information to establish whether dose reduction will eliminate episodes of falling asleep while engaged in activities of daily living.

-

PRECAUTIONS

Hypotension, Orthostatic Hypotension, and Syncope

Dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson’s disease patients has been associated with orthostatic hypotension. Entacapone enhances levodopa bioavailability and, therefore, might be expected to increase the occurrence of orthostatic hypotension. In controlled studies, approximately 1.2% and 0.8% of 200 mg entacapone and placebo patients, respectively, reported at least one episode of syncope. Reports of syncope were generally more frequent in patients in both treatment groups who had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hallucinations and Psychotic-Like BehaviorDopaminergic therapy in patients with Parkinson’s disease has been associated with hallucinations. In clinical studies, hallucinations led to drug discontinuation and premature withdrawal in 0.8% and 0% of patients treated with 200 mg entacapone and placebo, respectively. Hallucinations led to hospitalization in 1% and 0.3% of patients in the 200 mg entacapone and placebo groups, respectively. Agitation occurred in 1% of patients treated with entacapone and 0% treated with placebo.

Postmarketing reports indicate that patients may experience new or worsening mental status and behavioral changes, which may be severe, including psychotic-like behavior during entacapone treatment or after starting or increasing the dose of entacapone. Other drugs prescribed to improve the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease can have similar effects on thinking and behavior. Abnormal thinking and behavior can cause paranoid ideation, delusions, hallucinations, confusion, disorientation, aggressive behavior, agitation, and delirium. Psychotic-like behaviors were also observed during the clinical development of entacapone.

Patients with a major psychotic disorder should ordinarily not be treated with entacapone because of the risk of exacerbating psychosis. In addition, certain medications used to treat psychosis may exacerbate the symptoms of Parkinson's disease and may decrease the effectiveness of entacapone (see PRECAUTIONS).

Impulse Control and Compulsive Behaviors

Postmarketing reports suggest that patients treated with anti-Parkinson medications can experience intense urges to gamble, increased sexual urges, intense urges to spend money uncontrollably, and other intense urges. Patients may be unable to control these urges while taking one or more of the medications that are used for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and that increase central dopaminergic tone, including entacapone taken with levodopa and carbidopa. In some cases, although not all, these urges were reported to have stopped when the dose of anti-Parkinson medications was reduced or discontinued. Because patients may not recognize these behaviors as abnormal it is important for prescribers to specifically ask patients or their caregivers about the development of new or increased gambling urges, sexual urges, uncontrolled spending or other urges while being treated with entacapone. Physicians should consider dose reduction or stopping entacapone if a patient develops such urges while taking entacapone.

Diarrhea and ColitisIn clinical studies, diarrhea developed in 60 of 603 (10%) and 16 of 400 (4%) of patients treated with 200 mg entacapone and placebo, respectively. In patients treated with entacapone, diarrhea was generally mild to moderate in severity (8.6%) but was regarded as severe in 1.3%. Diarrhea resulted in withdrawal in 10 of 603 (1.7%) patients, 7 (1.2%) with mild and moderate diarrhea and 3 (0.5%) with severe diarrhea. Diarrhea generally resolved after discontinuation of entacapone. Two patients with diarrhea were hospitalized. Typically, diarrhea presents within 4 weeks to 12 weeks after entacapone is started, but it may appear as early as the first week and as late as many months after the initiation of treatment. Diarrhea may be associated with weight loss, dehydration, and hypokalemia.

Postmarketing experience has shown that diarrhea may be a sign of drug-induced microscopic colitis, primarily lymphocytic colitis. In these cases diarrhea has usually been moderate to severe, watery, and non-bloody, at times associated with dehydration, abdominal pain, weight loss, and hypokalemia. In the majority of cases, diarrhea and other colitis-related symptoms resolved or significantly improved when entacapone treatment was stopped. In some patients with biopsy confirmed colitis, diarrhea had resolved or significantly improved after discontinuation of entacapone but recurred after retreatment with entacapone.

If prolonged diarrhea is suspected to be related to entacapone, the drug should be discontinued and appropriate medical therapy considered. If the cause of prolonged diarrhea remains unclear or continues after stopping entacapone, then further diagnostic investigations including colonoscopy and biopsies should be considered.

Dyskinesia

Entacapone may potentiate the dopaminergic side effects of levodopa and may cause or exacerbate preexisting dyskinesia. Although decreasing the dose of levodopa may ameliorate this side effect, many patients in controlled studies continued to experience frequent dyskinesia despite a reduction in their dose of levodopa. The incidence of dyskinesia was 25% for treatment with entacapone and 15% for placebo. The incidence of study withdrawal for dyskinesia was 1.5% for 200 mg entacapone and 0.8% for placebo.

Other Events Reported With Dopaminergic Therapy

The events listed below are events associated with the use of drugs that increase dopaminergic activity.

Rhabdomyolysis: Cases of severe rhabdomyolysis have been reported following the approval of entacapone. Although the reactions typically occurred while patients were treated with entacapone, the complicated nature of these cases makes it difficult to determine what role, if any, entacapone played in their pathogenesis. Severe prolonged motor activity including dyskinesia may account for rhabdomyolysis. Signs and symptoms include fever, alteration of consciousness, myalgia, increased values of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and myoglobin.

Hyperpyrexia and Confusion: Cases of a symptom complex resembling neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) characterized by elevated temperature, muscular rigidity, altered consciousness, and elevated CPK have been reported in association with the rapid dose reduction or withdrawal of other dopaminergic drugs. In most of these cases, symptoms began after abrupt discontinuation of treatment with entacapone or reduction of its dose, or after the initiation of treatment with entacapone. The complicated nature of these cases makes it difficult to determine what role, if any, entacapone may have played in their pathogenesis. No cases have been reported following the abrupt withdrawal or dose reduction of entacapone treatment during clinical studies.

Prescribers should exercise caution when discontinuing entacapone treatment. When considered necessary, withdrawal should proceed slowly. If the decision is made to discontinue treatment with entacapone, recommendations include monitoring the patient closely and adjusting other dopaminergic treatments as needed. This syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who develops a high fever or severe rigidity. Tapering entacapone has not been systematically evaluated.

Fibrotic Complications: Cases of retroperitoneal fibrosis, pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening have been reported in some patients treated with ergot derived dopaminergic agents. These complications may resolve when the drug is discontinued, but complete resolution does not always occur. Although these adverse events are believed to be related to the ergoline structure of these compounds, whether other, nonergot derived drugs (e.g., entacapone) that increase dopaminergic activity can cause them is unknown. It should be noted that the expected incidence of fibrotic complications is so low that even if entacapone caused these complications at rates similar to those attributable to other dopaminergic therapies, it is unlikely that it would have been detected in a cohort of the size exposed to entacapone. Four cases of pulmonary fibrosis were reported during clinical development of entacapone; three of these patients were also treated with pergolide and one with bromocriptine. The duration of treatment with entacapone ranged from 7 months to 17 months.

Melanoma: Epidemiological studies have shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease have a higher risk (2- to approximately 6-fold higher) of developing melanoma than the general population. Whether the increased risk observed was due to Parkinson’s disease or other factors, such as drugs used to treat Parkinson’s disease, is unclear.

For the reasons stated above, patients and providers are advised to monitor for melanomas frequently and on a regular basis when using entacapone for any indication. Ideally, periodic skin examinations should be performed by appropriately qualified individuals (e.g., dermatologists).

Renal Toxicity

In a 1-year toxicity study, entacapone (plasma exposure 20 times that in humans receiving the maximum recommended daily dose of 1,600 mg) caused an increased incidence of nephrotoxicity in male rats that was characterized by regenerative tubules, thickening of basement membranes, infiltration of mononuclear cells, and tubular protein casts. These effects were not associated with changes in clinical chemistry parameters, and there is no established method for monitoring for the possible occurrence of these lesions in humans. Although this toxicity could represent a species- specific effect, there is not yet evidence that this is so.

Hepatic Impairment

Patients with hepatic impairment should be treated with caution. The AUC and Cmax of entacapone approximately doubled in patients with documented liver disease compared to controls (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Pharmacokinetics of Entacapone and DOSAGE ANDADMINISTRATION

Information for Patients

Instruct patients to take entacapone only as prescribed.

Inform patients that hallucinations and/or other psychotic-like behavior can occur.

Advise patients that they may develop postural (orthostatic) hypotension with or without symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, syncope, and sweating. Hypotension may occur more frequently during initial therapy. Accordingly, patients should be cautioned against rising rapidly after sitting or lying down, especially if they have been doing so for prolonged periods, and especially at the initiation of treatment with entacapone.

Advise patients that they should neither drive a car nor operate other complex machinery until they have gained sufficient experience on entacapone to gauge whether or not it affects their mental and/or motor performance adversely. Warn patients about the possibility of sudden onset of sleep during daily activities, in some cases without awareness or warning signs, when they are taking dopaminergic agents, including entacapone. Because of the possible additive sedative effects, caution should be used when patients are taking other CNS depressants in combination with entacapone.

Inform patients that nausea may occur, especially at the initiation of treatment with entacapone.

Inform patients that diarrhea may occur with entacapone and it may have a delayed onset. Sometimes prolonged diarrhea may be caused by colitis (inflammation of the large intestine). Patients with diarrhea should drink fluids to maintain adequate hydration and monitor for weight loss. If diarrhea associated with entacapone is prolonged, discontinuing the drug is expected to lead to resolution, if diarrhea continues after stopping entacapone, further diagnostic investigations may be needed.

Advise patients about the possibility of an increase in dyskinesia.

Tell patients that treatment with entacapone may cause a change in the color of their urine (a brownish orange discoloration) that is not clinically relevant. In controlled studies, 10% of patients treated with entacapone reported urine discoloration compared to 0% of placebo patients.

Although entacapone has not been shown to be teratogenic in animals, it is always given in conjunction with levodopa and carbidopa, which is known to cause visceral and skeletal malformations in rabbits. Accordingly, patients should be advised to notify their physicians if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy (see PRECAUTIONS, Pregnancy).

Entacapone is excreted into maternal milk in rats. Because of the possibility that entacapone may be excreted into human maternal milk, advise patients to notify their physicians if they intend to breastfeed or are breastfeeding an infant.

Tell patients and family members to notify their healthcare practitioner if they notice that the patient develops unusual urges or behaviors.

Laboratory Tests

Entacapone is a chelator of iron. The impact of entacapone on the body’s iron stores is unknown; however, a tendency towards decreasing serum iron concentrations was noted in clinical studies. In a controlled clinical study serum ferritin levels (as marker of iron deficiency and subclinical anemia) were not changed with entacapone compared to placebo after one year of treatment and there was no difference in rates of anemia or decreased hemoglobin levels.

Special PopulationsPatients with hepatic impairment should be treated with caution (see INDICATIONS, DOSAGE ANDADMINISTRATION).

Drug Interactions

In vitro studies of human CYP enzymes showed that entacapone inhibited the CYP enzymes 1A2, 2A6, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A only at very high concentrations (IC50 from 200 microM to over 1,000 microM; an oral 200 mg dose achieves a highest level of approximately 5 microM in people); these enzymes would therefore not be expected to be inhibited in clinical use.

In an interaction study in healthy volunteers, entacapone did not significantly change the plasma levels of S-warfarin while the AUC for R-warfarin increased on average by 18% [Cl90 11% to 26%], and the INR values increased on average by 13% [Cl90 6% to 19%]. Nevertheless, cases of significantly increased INR in patients concomitantly using warfarin have been reported during the postapproval use of entacapone. Therefore, monitoring of INR is recommended when entacapone treatment is initiated or when the dose is increased for patients receiving warfarin.

Protein Binding

Entacapone is highly protein bound (98%). In vitro studies have shown no binding displacement between entacapone and other highly bound drugs, such as warfarin, salicylic acid, phenylbutazone, and diazepam.

Drugs Metabolized by Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT)

See WARNINGS.

Hormone Levels

Levodopa is known to depress prolactin secretion and increase growth hormone levels. Treatment with entacapone coadministered with levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor does not change these effects.

Effect of Entacapone on the Metabolism of Other Drugs

See WARNINGS regarding concomitant use of entacapone and non-selective MAO inhibitors.

No interaction was noted with the MAO-B inhibitor selegiline in two multiple-dose interaction studies when entacapone was coadministered with a levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (n=29). More than 600 patients with Parkinson’s disease in clinical studies have used selegiline in combination with entacapone and levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor.

As most entacapone excretion is via the bile, caution should be exercised when drugs known to interfere with biliary excretion, glucuronidation, and intestinal beta-glucuronidase are given concurrently with entacapone. These include probenecid, cholestyramine, and some antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin, rifampicin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol).

No interaction with the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine was shown in a single-dose study with entacapone without coadministered levodopa and dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor.

Carcinogenesis

Two-year carcinogenicity studies of entacapone were conducted in mice and rats. In mice, no increase in tumors was observed at oral doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg/day. At the highest dose tested, plasma exposures (AUC) were 4 times higher than that in humans at the maximum recommended daily dose (MRDD) of 1,600 mg. In rats administered oral doses of 20, 90, or 400 mg/kg/day, an increased incidence of renal tubular adenomas and carcinomas was observed in males at the highest dose tested. Plasma AUCs at the higher dose not associated with increased renal tumors (90 mg/kg/day) were approximately 5 times that in humans at the MRDD of entacapone.

The carcinogenic potential of entacapone administered in combination with levodopa and carbidopa has not been evaluated.

Mutagenesis

Entacapone was mutagenic and clastogenic in the in vitro mouse lymphoma tk assay in the presence and absence of metabolic activation, and was clastogenic in cultured human lymphocytes in the presence of metabolic activation. Entacapone, either alone or in combination with levodopa and carbidopa, was not clastogenic in the in vivo mouse micronucleus test or mutagenic in the bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test).

Impairment of FertilityEntacapone did not impair fertility or general reproductive performance in rats treated with up to 700 mg/kg/day (plasma AUCs 28 times those in humans receiving the MRDD of 1,600 mg). Delayed mating, but no fertility impairment, was evident in female rats treated with 700 mg/kg/day of entacapone.

Pregnancy

In embryofetal development studies, entacapone was administered to pregnant animals throughout organogenesis at doses of up to 1,000 mg/kg/day in rats and 300 mg/kg/day in rabbits. Increased incidences of fetal variations were evident in litters from rats treated with the highest dose, in the absence of overt signs of maternal toxicity. The maternal plasma drug exposure (AUC) associated with this dose was approximately 34 times the estimated plasma exposure in humans receiving the maximum recommended daily dose (MRDD) of 1,600 mg. Increased frequencies of abortions, late and total resorptions, and decreased fetal weights were observed in the litters of rabbits treated with maternally toxic doses of 100 mg/kg/day (plasma AUCs 0.4 times those in humans receiving the MRDD) or greater. There was no evidence of teratogenicity in these studies.

However, when entacapone was administered to female rats prior to mating and during early gestation, an increased incidence of fetal eye anomalies (macrophthalmia, microphthalmia, anophthalmia) was observed in the litters of dams treated with doses of 160 mg/kg/day (plasma AUCs 7 times those in humans receiving the MRDD) or greater, in the absence of maternal toxicity. Administration of up to 700 mg/kg/day (plasma AUCs 28 times those in humans receiving the MRDD) to female rats during the latter part of gestation and throughout lactation produced no evidence of developmental impairment in the offspring.

Entacapone is always given concomitantly with levodopa and carbidopa, which is known to cause visceral and skeletal malformations in rabbits. The teratogenic potential of entacapone in combination with levodopa and carbidopa was not assessed in animals.

There is no experience from clinical studies regarding the use of entacapone in pregnant women. Therefore, entacapone should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Because clinical studies are conducted under widely varying conditions, the incidence of adverse reactions (number of unique patients experiencing an adverse reaction associated with treatment per total number of patients treated) observed in the clinical studies of a drug cannot be directly compared to the incidence of adverse reactions in the clinical studies of another drug and may not reflect the incidence of adverse reactions observed in practice.

A total of 1,450 patients with Parkinson’s disease were treated with entacapone in premarketing clinical studies. Included were patients with fluctuating symptoms, as well as those with stable responses to levodopa therapy. All patients received concomitant treatment with levodopa preparations, however, and were similar in other clinical aspects.

The most commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence at least 3% greater than placebo) in double- blind, placebo-controlled studies (N=1,003) associated with the use of entacapone were: dyskinesia, urine discoloration, diarrhea, nausea, hyperkinesia, abdominal pain, vomiting, and dry mouth.

Approximately 14% of the 603 patients given entacapone in the double-blind, placebo-controlled studies discontinued treatment due to adverse reactions, compared to 9% of the 400 patients who received placebo. The most frequent causes of discontinuation in decreasing order were: psychiatric disorders (2% vs. 1%), diarrhea (2% vs. 0%), dyskinesia and hyperkinesia (2% vs. 1%), nausea (2% vs. 1%), and abdominal pain (1% vs. 0%).

Adverse Event Incidence in Controlled Clinical Studies

Table 4 lists treatment-emergent adverse events that occurred in at least 1% of patients treated with entacapone participating in the double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and that were numerically more common in the entacapone group, compared to placebo. In these studies, either entacapone or placebo was added to levodopa and carbidopa (or levodopa and benserazide).

Table 4: Summary of Patients with Adverse Events after Start of Trial Drug Administration At least 1% in Entacapone Group and Greater Than Placebo

SYSTEM ORGAN CLASS

Preferred term

Entacapone

(n = 603)

% of patients

Placebo

(n = 400)

% of patients

SKIN AND APPENDAGES DISORDERS

Sweating increased

2

1

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM DISORDERS

Back pain

2

1

CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEMDISORDERS

Dyskinesia

25

15

Hyperkinesia

10

5

Hypokinesia

9

8

Dizziness

8

6

SPECIAL SENSES, OTHER DISORDERS

Taste perversion

1

0

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Anxiety

2

1

Somnolence

2

0

Agitation

1

0

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM DISORDERS

Nausea

14

8

Diarrhea

10

4

Abdominal pain

8

4

Constipation

6

4

Vomiting

4

1

Mouth dry

3

0

Dyspepsia

2

1

Flatulence

2

0

Gastritis

1

0

Gastrointestinal disorders

1

0

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM DISORDERS

Dyspnea

3

1

PLATELET, BLEEDING AND CLOTTING DISORDERS

Purpura

2

1

URINARY SYSTEM DISORDERS

Urine discoloration

10

0

BODY AS A WHOLE - GENERAL DISORDERS

Back pain

4

2

Fatigue

6

4

Asthenia

2

1

RESISTANCE MECHANISM DISORDERS

Infection bacterial

1

0

Effects of Gender and Age on Adverse Reactions

No differences were noted in the rate of adverse events attributable to entacapone by age or gender.

Postmarketing ReportsThe following spontaneous reports of adverse events temporally associated with entacapone have been identified since market introduction and are not listed in Table 4. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of unknown size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish causal relationship to entacapone exposure.

Hepatitis with mainly cholestatic features has been reported.

-

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

Entacapone is not a controlled substance. Animal studies to evaluate the drug abuse and potential dependence have not been conducted. Although clinical studies have not revealed any evidence of the potential for abuse, tolerance or physical dependence, systematic studies in humans designed to evaluate these effects have not been performed.

-

OVERDOSAGE

The postmarketing data include several cases of overdose. The highest reported dose of entacapone was at least 40,000 mg. The acute symptoms and signs commonly seen in these cases included somnolence and decreased activity, states related to depressed level of consciousness (e.g., coma, confusion and disorientation) and discolorations of skin, tongue, and urine, as well as restlessness, agitation, and aggression.

COMT inhibition by entacapone treatment is dose-dependent. A massive overdose of entacapone may theoretically produce a 100% inhibition of the COMT enzyme in humans, thereby preventing the metabolism of endogenous and exogenous catechols.

The highest daily dose given to humans was 2,400 mg, administered in one study as 400 mg six times daily with levodopa and carbidopa for 14 days in 15 Parkinson’s disease patients, and in another study as 800 mg three times daily for 7 days in 8 healthy volunteers. At this daily dose, the peak plasma concentrations of entacapone averaged 2 mcg per mL (at 45 minutes, compared to 1 mcg per mL and 1.2 mcg per mL with 200 mg entacapone at 45 minutes). Abdominal pain and loose stools were the most commonly observed adverse events during this study. Daily doses as high as 2,000 mg entacapone have been administered as 200 mg 10 times daily with levodopa and carbidopa or levodopa and benserazide for at least 1 year in 10 patients, for at least 2 years in 8 patients and for at least 3 years in 7 patients. Overall, however, clinical experience with daily doses above 1,600 mg is limited.

The range of lethal plasma concentrations of entacapone based on animal data was 80 mcg per mL to 130 mcg per mL in mice. Respiratory difficulties, ataxia, hypoactivity, and convulsions were observed in mice after high oral (gavage) doses.

Management of OverdoseManagement of entacapone overdose is symptomatic; there is no known antidote to entacapone. Hospitalization is advised, and general supportive care is indicated. There is no experience with hemodialysis or hemoperfusion, but these procedures are unlikely to be of benefit, because entacapone is highly bound to plasma proteins. An immediate gastric lavage and repeated doses of charcoal over time may hasten the elimination of entacapone by decreasing its absorption and reabsorption from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The adequacy of the respiratory and circulatory systems should be carefully monitored and appropriate supportive measures employed. The possibility of drug interactions, especially with catechol-structured drugs, should be borne in mind.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The recommended dose of entacapone is one 200 mg tablet administered concomitantly with each levodopa and carbidopa dose to a maximum of 8 times daily (200 mg x 8 = 1,600 mg per day).

Clinical experience with daily doses above 1,600 mg is limited.

Entacapone tablets should always be administered in association with levodopa and carbidopa. Entacapone has no antiparkinsonian effect of its own.

In clinical studies, the majority of patients required a decrease in daily levodopa dose if their daily dose of levodopa had been greater than or equal to 800 mg or if patients had moderate or severe dyskinesia before beginning treatment.

To optimize an individual patient’s response, reductions in daily levodopa dose or extending the interval between doses may be necessary. In clinical studies, the average reduction in daily levodopa dose was about 25% in those patients requiring a levodopa dose reduction. (More than 58% of patients with levodopa doses above 800 mg daily required such a reduction.)

Entacapone tablets can be combined with both the immediate and sustained-release formulations of levodopa and carbidopa.

Entacapone tablets may be taken with or without food (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

Patients With Impaired Hepatic Function: Patients with hepatic impairment should be treated with caution. The AUC and Cmax of entacapone approximately doubled in patients with documented liver disease, compared to controls. However, these studies were conducted with single-dose entacapone without levodopa and dopa decarboxylase inhibitor coadministration, and therefore the effects of liver disease on the kinetics of chronically administered entacapone have not been evaluated (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Pharmacokinetics of Entacapone).

Withdrawing Patients from Entacapone Tablets: Rapid withdrawal or abrupt reduction in the entacapone tablets dose could lead to emergence of signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Clinical Studies), and may lead to hyperpyrexia and confusion, a symptom complex resembling NMS (see PRECAUTIONS, Other Events Reported With DopaminergicTherapy). This syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who develops a high fever or severe rigidity. If a decision is made to discontinue treatment with entacapone tablets, patients should be monitored closely and other dopaminergic treatments should be adjusted as needed. Although tapering entacapone has not been systematically evaluated, it seems prudent to withdraw patients slowly if the decision to discontinue treatment is made.

-

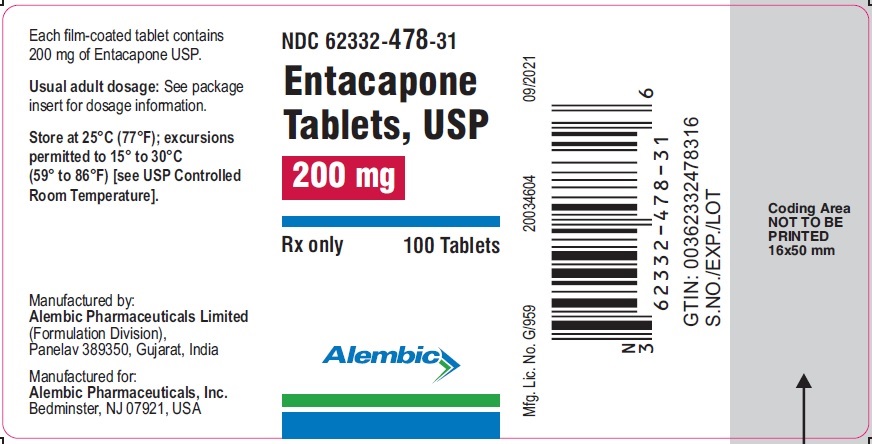

HOW SUPPLIED

Entacapone Tablets USP, 200 mg are brownish-orange colored, oval-shaped unscored film coated tablets debossed with “L 633” on one side and plain on the other side. Tablets are provided in HDPE containers as follows:

NDC: 62332-478-31 bottle of 100 tablets

NDC: 62332-478-91 bottle of 1,000 tablets

Store at 25°C (77°F); excursions permitted to 15° to 30°C (59° to 86°F) [see USP Controlled Room Temperature.]

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

For more information call Alembic Pharmaceuticals Limited at 1-866-210-9797.

Manufactured by:

Alembic Pharmaceuticals Limited

(Formulation Division),

Panelav 389350, Gujarat, India

Manufactured for:

Alembic Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Bedminster, NJ 07921, USA

Revised: 09/2021

- PACKAGE LABEL.PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 200 mg

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ENTACAPONE

entacapone tablet, film coatedProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 62332-478 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ENTACAPONE (UNII: 4975G9NM6T) (ENTACAPONE - UNII:4975G9NM6T) ENTACAPONE 200 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength MICROCRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) MANNITOL (UNII: 3OWL53L36A) CROSCARMELLOSE SODIUM (UNII: M28OL1HH48) SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) HYDROGENATED COTTONSEED OIL (UNII: Z82Y2C65EA) HYPROMELLOSE, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) GLYCERIN (UNII: PDC6A3C0OX) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) FERRIC OXIDE YELLOW (UNII: EX438O2MRT) SUCROSE (UNII: C151H8M554) POLYSORBATE 80 (UNII: 6OZP39ZG8H) FERRIC OXIDE RED (UNII: 1K09F3G675) Product Characteristics Color BROWN (brownish-orange) Score no score Shape OVAL Size 17mm Flavor Imprint Code L633 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 62332-478-31 100 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 01/06/2022 2 NDC: 62332-478-91 1000 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 01/06/2022 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA212601 01/06/2022 Labeler - Alembic Pharmaceuticals Inc. (079288842) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Alembic Pharmaceuticals Limited 650574671 MANUFACTURE(62332-478)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.