Tetrabenazine by Precision Dose Inc. TETRABENAZINE tablet

Tetrabenazine by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Tetrabenazine by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Precision Dose Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use TETRABENAZINE TABLETS safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for TETRABENAZINE TABLETS.

TETRABENAZINE tablets, for oral use

Initial U.S. Approval: 2008WARNING: DEPRESSION AND SUICIDALITY

See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

- Increases the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington’s disease. (5.1)

- Balance risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for control of chorea when considering the use of tetrabenazine tablets. (5.2)

- Monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. (5.1)

- Inform patients, caregivers and families of the risk of depression and suicidality and instruct to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. (5.1)

- Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation. (5.1).

- Tetrabenazine tablets are contraindicated in patients who are actively suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression. (4, 5.1)

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Tetrabenazine tablets are a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT) inhibitor indicated for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington’s disease. (1)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

- Individualization of dose with careful weekly titration is required. The 1st week’s starting dose is 12.5 mg daily; 2nd week, 25 mg (12.5 mg twice daily); then slowly titrate at weekly intervals by 12.5 mg to a tolerated dose that reduces chorea. (2.1, 2.2)

- Doses of 37.5 mg and up to 50 mg per day should be administered in three divided doses per day with a maximum recommended single dose not to exceed 25 mg. (2.2)

- Patients requiring doses above 50 mg per day should be genotyped for the drug metabolizing enzyme CYP2D6 to determine if the patient is a poor metabolizer (PM) or an extensive metabolizer (EM). (2.2, 5.3)

- Maximum daily dose in PMs: 50 mg with a maximum single dose of 25 mg (2.2)

- Maximum daily dose in EMs and intermediate metabolizers (IMs): 100 mg with a maximum single dose of 37.5 mg (2.2)

- If serious adverse reactions occur, titration should be stopped and the dose should be reduced. If the adverse reaction(s) do not resolve, consider withdrawal of tetrabenazine tablets. (2.2)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Tablets: 12.5 mg non-scored and 25 mg scored (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Periodically reevaluate the benefit and potential for adverse effects such as worsening mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. (5.2)

- Do not exceed 50 mg/day and the maximum single dose should not exceed 25 mg if administered in conjunction with a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine). (5.3, 7.1)

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS): Discontinue if this occurs. (5.4, 7.6)

- Restlessness, agitation, akathisia and parkinsonism: Reduce dose or discontinue if occurs. (5.5, 5.6)

- Sedation/Somnolence: May impair patient’s ability to drive or operate complex machinery (5.7)

- QTc prolongation: Not recommended in combination with other drugs that prolong QTc (5.8)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most common adverse reactions (>10% and at least 5% greater than placebo) were: Sedation/somnolence, fatigue, insomnia, depression, akathisia, anxiety/anxiety aggravated, nausea. (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Precision Dose, Inc. at 1-844-668-3942 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 8/2023

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNING: DEPRESSION AND SUICIDALITY

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 General Dosing Considerations

2.2 Individualization of Dose

2.3 Dosage Adjustment with CYP2D6 Inhibitors

2.4 Discontinuation of Treatment

2.5 Resumption of Treatment

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Depression and Suicidality

5.2 Clinical Worsening and Adverse Effects

5.3 Laboratory Tests

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

5.5 Akathisia, Restlessness, and Agitation

5.6 Parkinsonism

5.7 Sedation and Somnolence

5.8 QTc Prolongation

5.9 Hypotension and Orthostatic Hypotension

5.10 Hyperprolactinemia

5.11 Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Strong CYP2D6 Inhibitors

7.2 Reserpine

7.3 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

7.4 Alcohol or Other Sedating Drugs

7.5 Drugs That Cause QTc Prolongation

7.6 Neuroleptic Drugs

7.7 Concomitant Deutetrabenazine or Valbenazine

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Hepatic Impairment

8.7 Poor or Extensive CYP2D6 Metabolizers

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

16.1 How Supplied

16.2 Storage

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: DEPRESSION AND SUICIDALITY

Tetrabenazine tablets can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington’s disease. Anyone considering the use of tetrabenazine tablets must balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for control of chorea. Close observation of patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior should accompany therapy. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed of the risk of depression and suicidality and should be instructed to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician.

Particular caution should be exercised in treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation, which are increased in frequency in Huntington’s disease. Tetrabenazine tablets are contraindicated in patients who are actively suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression [see Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- 1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 General Dosing Considerations

The chronic daily dose of tetrabenazine tablets used to treat chorea associated with Huntington’s disease (HD) is determined individually for each patient. When first prescribed, tetrabenazine tablets therapy should be titrated slowly over several weeks to identify a dose of tetrabenazine tablets that reduces chorea and is tolerated. Tetrabenazine tablets can be administered without regard to food [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.2 Individualization of Dose

The dose of tetrabenazine tablets should be individualized.

Dosing Recommendations Up to 50 mg per day

The starting dose should be 12.5 mg per day given once in the morning. After one week, the dose should be increased to 25 mg per day given as 12.5 mg twice a day. Tetrabenazine tablets should be titrated up slowly at weekly intervals by 12.5 mg daily, to allow the identification of a tolerated dose that reduces chorea. If a dose of 37.5 to 50 mg per day is needed, it should be given in a three times a day regimen. The maximum recommended single dose is 25 mg. If adverse reactions such as akathisia, restlessness, parkinsonism, depression, insomnia, anxiety or sedation occur, titration should be stopped and the dose should be reduced. If the adverse reaction does not resolve, consideration should be given to withdrawing tetrabenazine tablets treatment or initiating other specific treatment (e.g., antidepressants) [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

Dosing Recommendations Above 50 mg per day

Patients who require doses of tetrabenazine tablets greater than 50 mg per day should be first tested and genotyped to determine if they are poor metabolizers (PMs) or extensive metabolizers (EMs) by their ability to express the drug metabolizing enzyme, CYP2D6. The dose of tetrabenazine tablets should then be individualized accordingly to their status as PMs or EMs [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Extensive and Intermediate CYP2D6 Metabolizers

Genotyped patients who are identified as extensive (EMs) or intermediate metabolizers (IMs) of CYP2D6, who need doses of tetrabenazine tablets above 50 mg per day, should be titrated up slowly at weekly intervals by 12.5 mg daily, to allow the identification of a tolerated dose that reduces chorea. Doses above 50 mg per day should be given in a three times a day regimen. The maximum recommended daily dose is 100 mg and the maximum recommended single dose is 37.5 mg. If adverse reactions such as akathisia, parkinsonism, depression, insomnia, anxiety or sedation occur, titration should be stopped and the dose should be reduced. If the adverse reaction does not resolve, consideration should be given to withdrawing tetrabenazine tablets treatment or initiating other specific treatment (e.g., antidepressants) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Poor CYP2D6 Metabolizers

In PMs, the initial dose and titration is similar to EMs except that the recommended maximum single dose is 25 mg, and the recommended daily dose should not exceed a maximum of 50 mg [see Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.3 Dosage Adjustment with CYP2D6 Inhibitors

Strong CYP2D6 Inhibitors

Medications that are strong CYP2D6 inhibitors such as quinidine or antidepressants (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine) significantly increase the exposure to α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ; therefore, the total dose of tetrabenazine tablets should not exceed a maximum of 50 mg and the maximum single dose should not exceed 25 mg [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Drug Interactions (7.1), Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.4 Discontinuation of Treatment

Treatment with tetrabenazine tablets can be discontinued without tapering. Re-emergence of chorea may occur within 12 to 18 hours after the last dose of tetrabenazine tablets [see Drug Abuse and Dependence (9.2)].

-

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Tetrabenazine tablets are available in the following strengths and packages:

The 12.5 mg tetrabenazine tablets are white cylindrical, biplanar tablets with beveled edges, debossed ‘707’ on one side and plain on the other side.

The 25 mg tetrabenazine tablets are yellowish-buff, cylindrical, biplanar tablets with beveled edges, debossed ‘708’ on one side and scored on the other side.

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

Tetrabenazine tablets are contraindicated in patients:

- Who are actively suicidal, or in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- With hepatic impairment [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

- Taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Tetrabenazine tablets should not be used in combination with an MAOI, or within a minimum of 14 days of discontinuing therapy with an MAOI [see Drug Interactions (7.3)].

- Taking reserpine. At least 20 days should elapse after stopping reserpine before starting tetrabenazine tablets [see Drug Interactions (7.2)].

- Taking deutetrabenazine or valbenazine [see Drug Interactions (7.7)].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Depression and Suicidality

Patients with Huntington’s disease are at increased risk for depression, suicidal ideation or behaviors (suicidality). Tetrabenazine tablets increase the risk for suicidality in patients with HD.

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chorea associated with Huntington’s disease, 10 of 54 patients (19%) treated with tetrabenazine tablets were reported to have an adverse event of depression or worsening depression compared to none of the 30 placebo-treated patients. In two open-label studies (in one study, 29 patients received tetrabenazine tablets for up to 48 weeks; in the second study, 75 patients received tetrabenazine tablets for up to 80 weeks), the rate of depression/worsening depression was 35%.

In all of the HD chorea studies of tetrabenazine tablets (n=187), one patient committed suicide, one attempted suicide, and six had suicidal ideation.

When considering the use of tetrabenazine tablets, the risk of suicidality should be balanced against the need for treatment of chorea. All patients treated with tetrabenazine tablets, should be observed for new or worsening depression or suicidality. If depression or suicidality does not resolve, consider discontinuing treatment with tetrabenazine tablets.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed of the risks of depression, worsening depression, and suicidality associated with tetrabenazine tablets, and should be instructed to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Patients with HD who express suicidal ideation should be evaluated immediately.

5.2 Clinical Worsening and Adverse Effects

Huntington’s disease is a progressive disorder characterized by changes in mood, cognition, chorea, rigidity, and functional capacity over time. In a 12-week controlled trial, tetrabenazine tablets were also shown to cause slight worsening in mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. Whether these effects persist, resolve, or worsen with continued treatment is unknown.

Prescribers should periodically re-evaluate the need for tetrabenazine tablets in their patients by assessing the effect on chorea and possible adverse effects, including depression and suicidality, cognitive decline, parkinsonism, dysphagia, sedation/somnolence, akathisia, restlessness, and disability. It may be difficult to distinguish between adverse reactions and progression of the underlying disease; decreasing the dose or stopping the drug may help the clinician distinguish between the two possibilities. In some patients, underlying chorea itself may improve over time, decreasing the need for tetrabenazine tablets.

5.3 Laboratory Tests

Before prescribing a daily dose of tetrabenazine tablets that is greater than 50 mg per day, patients should be genotyped to determine if they express the drug metabolizing enzyme, CYP2D6. CYP2D6 testing is necessary to determine whether patients are poor metabolizers (PMs), extensive (EMs) or intermediate metabolizers (IMs) of tetrabenazine tablets.

Patients who are PMs of tetrabenazine tablets will have substantially higher levels of the primary drug metabolites (about 3-fold for α-HTBZ and 9-fold for β-HTBZ) than patients who are EMs. The dosage should be adjusted according to a patient’s CYP2D6 metabolizer status. In patients who are identified as CYP2D6 PMs, the maximum recommended total daily dose is 50 mg and the maximum recommended single dose is 25 mg [see Dosage and Administration (2.2), Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with tetrabenazine tablets and other drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission [see Drug Interactions (7.6)]. Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatinine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure. The diagnosis of NMS can be complicated; other serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection), and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal disorders can present with similar signs and symptoms. Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever, and primary central nervous system pathology.

The management of NMS should include (1) immediate discontinuation of tetrabenazine tablets (2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and (3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for NMS.

Recurrence of NMS has been reported with resumption of drug therapy. If treatment with tetrabenazine tablets is needed after recovery from NMS, patients should be monitored for signs of recurrence.

5.5 Akathisia, Restlessness, and Agitation

Tetrabenazine tablets may increase the risk of akathisia, restlessness, and agitation.

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chorea associated with HD, akathisia was observed in 10 (19%) of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients and 0% of placebo-treated patients. In an 80-week, open-label study, akathisia was observed in 20% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients.

Patients receiving tetrabenazine tablets should be monitored for the presence of akathisia. Patients receiving tetrabenazine tablets should also be monitored for signs and symptoms of restlessness and agitation, as these may be indicators of developing akathisia. If a patient develops akathisia, the tetrabenazine tablets dose should be reduced; however, some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

5.6 Parkinsonism

Tetrabenazine tablets can cause parkinsonism.

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chorea associated with HD, symptoms suggestive of parkinsonism (i.e., bradykinesia, hypertonia and rigidity) were observed in 15% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients compared to 0% of placebo-treated patients. In 48-week and 80-week, open-label studies, symptoms suggestive of parkinsonism were observed in 10% and 3% of tetrabenazine tablets- treated patients, respectively.

Because rigidity can develop as part of the underlying disease process in Huntington’s disease, it may be difficult to distinguish between this drug-induced adverse reaction and progression of the underlying disease process. Drug-induced parkinsonism has the potential to cause more functional disability than untreated chorea for some patients with Huntington’s disease. If a patient develops parkinsonism during treatment with tetrabenazine tablets, dose reduction should be considered; in some patients, discontinuation of therapy may be necessary.

5.7 Sedation and Somnolence

Sedation is the most common dose-limiting adverse reaction of tetrabenazine tablets. In a 12-week, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with chorea associated with HD, sedation/somnolence occured in 17/54 (31%) tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients and in 1 (3%) of placebo-treated patient. Sedation was the reason upward titration of tetrabenazine tablets were stopped and/or the dose of tetrabenazine tablets was decreased in 15/54 (28%) patients. In all but one case, decreasing the dose of tetrabenazine tablets resulted in decreased sedation. In 48-week and 80-week, open-label studies, sedation/somnolence occurred in 17% and 57% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients, respectively. In some patients, sedation occurred at doses that were lower than recommended doses.

Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness to maintain the safety of themselves or others, such as operating a motor vehicle or operating hazardous machinery, until they are on a maintenance dose of tetrabenazine tablets and know how the drug affects them.

5.8 QTc Prolongation

Tetrabenazine tablets cause a small increase (about 8 msec) in the corrected QT (QTc) interval. QT prolongation can lead to development of torsade de pointes-type ventricular tachycardia with the risk increasing as the degree of prolongation increases [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)]. The use of tetrabenazine tablets should be avoided in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong QTc, including antipsychotic medications (e.g., chlorpromazine, haloperidol, thioridazine, ziprasidone), antibiotics (e.g., moxifloxacin), Class 1A (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) and Class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic medications or any other medications known to prolong the QTc interval [see Drug Interactions (7.5)].

Tetrabenazine tablets should also be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias. Certain circumstances may increase the risk of the occurrence of torsade de pointes and/or sudden death in association with the use of drugs that prolong the QTc interval, including (1) bradycardia; (2) hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia; (3) concomitant use of other drugs that prolong the QTc interval; and (4) presence of congenital prolongation of the QT interval [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

5.9 Hypotension and Orthostatic Hypotension

Tetrabenazine tablets induced postural dizziness in healthy volunteers receiving single doses of 25 or 50 mg. One subject had syncope, and one subject with postural dizziness had documented orthostasis. Dizziness occurred in 4% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients (vs. none on placebo) in the 12-week, controlled trial; however, blood pressure was not measured during these events. Monitoring of vital signs on standing should be considered in patients who are vulnerable to hypotension.

5.10 Hyperprolactinemia

Tetrabenazine tablets elevate serum prolactin concentrations in humans. Following administration of 25 mg to healthy volunteers, peak plasma prolactin levels increased 4- to 5-fold. Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one third of human breast cancers are prolactin-dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if tetrabenazine tablets are being considered for a patient with previously detected breast cancer. Although amenorrhea, galactorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence can be caused by elevated serum prolactin concentrations, the clinical significance of elevated serum prolactin concentrations for most patients is unknown. Chronic increase in serum prolactin levels (although not evaluated in the tetrabenazine tablets development program) has been associated with low levels of estrogen and increased risk of osteoporosis. If there is a clinical suspicion of symptomatic hyperprolactinemia, appropriate laboratory testing should be done and consideration should be given to discontinuation of tetrabenazine tablets.

5.11 Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues

Since tetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues, it could accumulate in these tissues over time. This raises the possibility that tetrabenazine tablets may cause toxicity in these tissues after extended use. Neither ophthalmologic nor microscopic examination of the eye has been conducted in the chronic toxicity studies in a pigmented species, such as dogs. Ophthalmologic monitoring in humans was inadequate to exclude the possibility of injury occurring after long-term exposure.

The clinical relevance of tetrabenazine tablet’s binding to melanin-containing tissues is unknown. Although there are no specific recommendations for periodic ophthalmologic monitoring, prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are described below and elsewhere in the labeling:

- Depression and Suicidality [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Akathisia, Restlessness, and Agitation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Parkinsonism [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Sedation and Somnolence [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- QTc Prolongation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Hypotension and Orthostatic Hypotension [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

- Hyperprolactinemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.10)]

- Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

During its development, tetrabenazine tablets were administered to 773 unique subjects and patients. The conditions and duration of exposure to tetrabenazine tablets varied greatly and included single-dose and multiple-dose clinical pharmacology studies in healthy volunteers (n=259) and open-label (n=529) and double-blind studies (n=84) in patients.

In a randomized, 12-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial of HD patients, adverse reactions were more common in the tetrabenazine tablets group than in the placebo group. Forty-nine of 54 (91%) patients who received tetrabenazine tablets experienced one or more adverse reactions at any time during the study. The most common adverse reactions (over 10%, and at least 5% greater than placebo) were sedation/somnolence, fatigue, insomnia, depression, akathisia, anxiety/anxiety aggravated, and nausea.

Adverse Reactions Occurring in ≥4% of Patients

The number and percentage of the most common adverse reactions that occurred at any time during the study in ≥4% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients, and with a greater frequency than in placebo-treated patients, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Adverse Reactions in a 12-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Patients with Huntington’s Disease Adverse Reaction

Tetrabenazine Tablets

n = 54

%Placebo

n = 30

%Sedation/somnolence

31

3

Insomnia

22

0

Fatigue

22

13

Depression

19

0

Akathisia

19

0

Anxiety/anxiety aggravated

15

3

Fall

15

13

Nausea

13

7

Upper respiratory tract infection

11

7

Irritability

9

3

Balance difficulty

9

0

Parkinsonism/bradykinesia

9

0

Vomiting

6

3

Laceration (head)

6

0

Ecchymosis

6

0

Decreased appetite

4

0

Obsessive reaction

4

0

Dizziness

4

0

Dysarthria

4

0

Unsteady gait

4

0

Headache

4

3

Shortness of breath

4

0

Bronchitis

4

0

Dysuria

4

0

Dose escalation was discontinued or dosage of study drug was reduced because of one or more adverse reactions in 28 of 54 (52%) patients randomized to tetrabenazine tablets. These adverse reactions consisted of sedation (15), akathisia (7), parkinsonism (4), depression (3), anxiety (2), fatigue (1) and diarrhea (1). Some patients had more than one AR and are, therefore, counted more than once.

Adverse Reactions Due to Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Table 2 describes the incidence of events considered to be extrapyramidal adverse reactions which occurred at a greater frequency in tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients compared to placebo-treated patients.

Table 2. Adverse Reactions Due to Extrapyramidal Symptoms in a 12-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled in Patients with Huntington’s disease. - * Patients with the following adverse event preferred terms were counted in this category: akathisia, hyperkinesia, restlessness.

- † Patients with the following adverse event preferred terms were counted in this category: bradykinesia, parkinsonism, extrapyramidal disorder, hypertonia.

Patients may have had events in more than one category.Tetrabenazine Tablets

n = 54

%Placebo

n = 30

%Akathisia*

19

0

Extrapyramidal event†

15

0

Any extrapyramidal event

33

0

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is a component of HD. However, drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission have been associated with esophageal dysmotility and dysphagia. Dysphagia may be associated with aspiration pneumonia. In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chorea associated with HD, dysphagia was observed in 4% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients and 3% of placebo-treated patients. In 48-week and 80-week, open-label studies, dysphagia was observed in 10% and 8% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients, respectively. Some of the cases of dysphagia were associated with aspiration pneumonia. Whether these events were related to treatment is unknown.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of tetrabenazine tablets. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Nervous system disorders: tremor

Psychiatric disorders: confusion, worsening aggression

Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders: pneumonia

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: hyperhidrosis, skin rash

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Strong CYP2D6 Inhibitors

In vitro studies indicate that α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ are substrates for CYP2D6. Strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, quinidine) markedly increase exposure to these metabolites. A reduction in tetrabenazine tablets dose may be necessary when adding a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine, quinidine) in patients maintained on a stable dose of tetrabenazine tablets. The daily dose of tetrabenazine tablets should not exceed 50 mg per day and the maximum single dose of tetrabenazine tablets should not exceed 25 mg in patients taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors [see Dosage and Administration (2.3), Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.2 Reserpine

Reserpine binds irreversibly to VMAT2, and the duration of its effect is several days. Prescribers should wait for chorea to re-emerge before administering tetrabenazine tablets to avoid overdosage and major depletion of serotonin and norepinephrine in the CNS. At least 20 days should elapse after stopping reserpine before starting tetrabenazine tablets. Tetrabenazine tablets and reserpine should not be used concomitantly [see Contraindications (4)].

7.3 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Tetrabenazine tablets are contraindicated in patients taking MAOIs. Tetrabenazine tablets should not be used in combination with an MAOI, or within a minimum of 14 days of discontinuing therapy with an MAOI [see Contraindications (4)].

7.4 Alcohol or Other Sedating Drugs

Concomitant use of alcohol or other sedating drugs may have additive effects and worsen sedation and somnolence [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

7.5 Drugs That Cause QTc Prolongation

Tetrabenazine tablets cause a small prolongation of QTc (about 8 msec), concomitant use with other drugs that are known to cause QTc prolongation should be avoided, these including antipsychotic medications (e.g., chlorpromazine, haloperidol, thioridazine, ziprasidone), antibiotics (e.g., moxifloxacin), Class 1A (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) and Class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic medications or any other medications known to prolong the QTc interval. Tetrabenazine tablets should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias. Certain conditions may increase the risk for torsade de pointes or sudden death such as (1) bradycardia; (2) hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia; (3) concomitant use of other drugs that prolong the QTc interval; and (4) presence of congenital prolongation of the QT interval [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8), Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

7.6 Neuroleptic Drugs

The risk for Parkinsonism, NMS, and akathisia may be increased by concomitant use of tetrabenazine tablets and dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, thioridazine, ziprasidone) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4, 5.5, 5.6)].

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Risk Summary

There are no adequate data on the developmental risk associated with the use of tetrabenazine tablets in pregnant women. Administration of tetrabenazine to rats throughout pregnancy and lactation resulted in an increase in stillbirths and postnatal offspring mortality. Administration of a major human metabolite of tetrabenazine to rats during pregnancy or during pregnancy and lactation produced adverse effects on the developing fetus and offspring (increased mortality, decreased growth, and neurobehavioral and reproductive impairment). The adverse developmental effects of tetrabenazine and a major human metabolite of tetrabenazine in rats occurred at clinically relevant doses [see Data].

In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 to 4% and 15 to 20%, respectively. The background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown.

Data

Animal Data

Tetrabenazine had no clear effects on embryofetal development when administered to pregnant rats throughout the period of organogenesis at oral doses up to 30 mg/kg/day (or 3 times the maximum recommended human dose [MRHD] of 100 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis). Tetrabenazine had no effects on embryofetal development when administered to pregnant rabbits during the period of organogenesis at oral doses up to 60 mg/kg/day (or 12 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

When tetrabenazine (5, 15, and 30 mg/kg/day) was orally administered to pregnant rats from the beginning of organogenesis through the lactation period, an increase in stillbirths and offspring postnatal mortality was observed at 15 and 30 mg/kg/day and delayed pup maturation was observed at all doses. A no-effect dose for pre- and postnatal developmental toxicity in rats was not identified. The lowest dose tested (5 mg/kg/day) was less than the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

Because rats dosed orally with tetrabenazine do not produce 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ, a major human metabolite of tetrabenazine, the metabolite was directly administered to pregnant and lactating rats. Oral administration of 9-desmethyl- β -DHTBZ (8, 15, and 40 mg/kg/day) throughout the period of organogenesis produced increases in embryofetal mortality at 15 and 40 mg/kg/day and reductions in fetal body weights at 40 mg/kg/day, which was also maternally toxic. When 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ (8, 15, and 40 mg/kg/day) was orally administered to pregnant rats from the beginning of organogenesis through the lactation period, increases in gestation duration, stillbirths, and offspring postnatal mortality (40 mg/kg/day); decreases in pup weights (40 mg/kg/day); and neurobehavioral (increased activity, learning and memory deficits) and reproductive (decreased litter size) impairment (15 and 40 mg/kg/day) were observed. Maternal toxicity was seen at the highest dose. The no-effect dose for developmental toxicity in rats (8 mg/kg/day) was associated with plasma exposures (AUC) of 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ in pregnant rats lower than that in humans at the MRHD.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

There are no data on the presence of tetrabenazine or its metabolites in human milk, the effects on the breastfed infant, or the effects of the drug on milk production.

The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for tetrabenazine tablets and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from tetrabenazine tablets or from the underlying maternal condition.

8.5 Geriatric Use

The pharmacokinetics of tetrabenazine tablets and its primary metabolites have not been formally studied in geriatric subjects.

8.6 Hepatic Impairment

Because the safety and efficacy of the increased exposure to tetrabenazine tablets and other circulating metabolites are unknown, it is not possible to adjust the dosage of tetrabenazine tablets in hepatic impairment to ensure safe use. The use of tetrabenazine tablets in patients with hepatic impairment is contraindicated [see Contraindications (4), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.7 Poor or Extensive CYP2D6 Metabolizers

Patients who require doses of tetrabenazine tablets greater than 50 mg per day, should be first tested and genotyped to determine if they are poor (PMs) or extensive metabolizers (EMs) by their ability to express the drug metabolizing enzyme, CYP2D6. The dose of tetrabenazine tablets should then be individualized accordingly to their status as either poor (PMs) or extensive metabolizers (EMs) [see Dosage and Administration (2.2), Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Poor Metabolizers

Poor CYP2D6 metabolizers (PMs) will have substantially higher levels of exposure to the primary metabolites (about 3-fold for α-HTBZ and 9-fold for β-HTBZ) compared to EMs. The dosage should, therefore, be adjusted according to a patient’s CYP2D6 metabolizer status by limiting a single dose to a maximum of 25 mg and the recommended daily dose to not exceed a maximum of 50 mg/day in patients who are CYP2D6 PMs [see Dosage and Administration (2.2), Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Extensive/Intermediate Metabolizers

In extensive (EMs) or intermediate metabolizers (IMs), the dosage of tetrabenazine tablets can be titrated to a maximum single dose of 37.5 mg and a recommended maximum daily dose of 100 mg [see Dosage and Administration (2.2), Drug Interactions (7.1), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

-

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

Clinical trials did not reveal patients developed drug seeking behaviors, though these observations were not systematic. Abuse has not been reported from the postmarketing experience in countries where tetrabenazine tablets have been marketed.

As with any CNS-active drug, prescribers should carefully evaluate patients for a history of drug abuse and follow such patients closely, observing them for signs of tetrabenazine tablets misuse or abuse (such as development of tolerance, increasing dose requirements, drug-seeking behavior).

Abrupt discontinuation of tetrabenazine tablets from patients did not produce symptoms of withdrawal or a discontinuation syndrome; only symptoms of the original disease were observed to re-emerge [see Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

Three episodes of overdose occurred in the open-label trials performed in support of registration. Eight cases of overdose with tetrabenazine tablets have been reported in the literature. The dose of tetrabenazine tablets in these patients ranged from 100 mg to 1 g. Adverse reactions associated with tetrabenazine tablets overdose include acute dystonia, oculogyric crisis, nausea and vomiting, sweating, sedation, hypotension, confusion, diarrhea, hallucinations, rubor, and tremor.

Treatment should consist of those general measures employed in the management of overdosage with any CNS-active drug. General supportive and symptomatic measures are recommended. Cardiac rhythm and vital signs should be monitored. In managing overdosage, the possibility of multiple drug involvement should always be considered. The physician should consider contacting a poison control center on the treatment of any overdose.

-

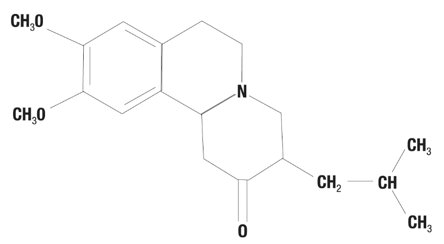

11 DESCRIPTION

Tetrabenazine tablets are a monoamine depletor for oral administration. The molecular weight of tetrabenazine is 317.43; the pKa is 6.51. Tetrabenazine is a hexahydro-dimethoxy-benzoquinolizine derivative and has the following chemical name: cis rac –1,3,4,6,7,11b-hexahydro-9,10-dimethoxy-3-(2-methylpropyl)-2H-benzo[a] quinolizin-2-one.

The empirical formula C19H27NO3 is represented by the following structural formula:

Tetrabenazine is a white to slightly yellow crystalline powder that is sparingly soluble in water and soluble in ethanol.

Each tetrabenazine tablet contains either 12.5 or 25 mg of tetrabenazine as the active ingredient.

Tetrabenazine tablets contain tetrabenazine as the active ingredient and the following inactive ingredients: lactose, magnesium stearate, maize starch, and talc. The 25 mg strength tablets also contain yellow iron oxide as an inactive ingredient.

Tetrabenazine tablets are supplied as a yellowish-buff, scored tablet containing 25 mg of tetrabenazine or as a white, non-scored tablet containing 12.5 mg of tetrabenazine.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanism by which tetrabenazine exerts its anti-chorea effects is unknown but is believed to be related to its effect as a reversible depletor of monoamines (such as dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and histamine) from nerve terminals. Tetrabenazine reversibly inhibits the human vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) (Ki ≈ 100 nM), resulting in decreased uptake of monoamines into synaptic vesicles and depletion of monoamine stores. Human VMAT2 is also inhibited by dihydrotetrabenazine (HTBZ), a mixture of α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ. α- and β-HTBZ, major circulating metabolites in humans, exhibit high in vitro binding affinity to bovine VMAT2. Tetrabenazine exhibits weak in vitro binding affinity at the dopamine D2 receptor (Ki = 2100 nM).

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

QTc Prolongation

The effect of a single 25 or 50 mg dose of tetrabenazine tablets on the QT interval was studied in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study in healthy male and female subjects with moxifloxacin as a positive control. At 50 mg, tetrabenazine tablets caused an approximately 8 msec mean increase in QTc (90% CI: 5.0, 10.4 msec). Additional data suggest that inhibition of CYP2D6 in healthy subjects given a single 50 mg dose of tetrabenazine tablets does not further increase the effect on the QTc interval. Effects at higher exposures to either tetrabenazine tablets or its metabolites have not been evaluated [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8), Drug Interactions (7.5)].

Melanin Binding

Tetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues (i.e., eye, skin, fur) in pigmented rats. After a single oral dose of radiolabeled tetrabenazine, radioactivity was still detected in eye and fur at 21 days post dosing [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)].

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Following oral administration of tetrabenazine, the extent of absorption is at least 75%. After single oral doses ranging from 12.5 to 50 mg, plasma concentrations of tetrabenazine are generally below the limit of detection because of the rapid and extensive hepatic metabolism of tetrabenazine by carbonyl reductase to the active metabolites α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ. α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ are metabolized principally by CYP2D6. Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ are reached within 1 to 1½ hours post-dosing. α-HTBZ is subsequently metabolized to a minor metabolite, 9-desmethyl-α-DHTBZ. β-HTBZ is subsequently metabolized to another major circulating metabolite, 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ, for which Cmax is reached approximately 2 hours post-dosing.

Food Effects

The effects of food on the bioavailability of tetrabenazine tablets were studied in subjects administered a single dose with and without food. Food had no effect on mean plasma concentrations, Cmax, or the area under the concentration time course (AUC) of α-HTBZ or β-HTBZ [see Dosage and Administration (2.1)].

Distribution

Results of PET-scan studies in humans show that radioactivity is rapidly distributed to the brain following intravenous injection of 11C-labeled tetrabenazine or α-HTBZ, with the highest binding in the striatum and lowest binding in the cortex.

The in vitro protein binding of tetrabenazine, α-HTBZ, and β-HTBZ was examined in human plasma for concentrations ranging from 50 to 200 ng/mL. Tetrabenazine binding ranged from 82% to 85%, α-HTBZ binding ranged from 60% to 68%, and β-HTBZ binding ranged from 59% to 63%.

Metabolism

After oral administration in humans, at least 19 metabolites of tetrabenazine have been identified. α-HTBZ, β-HTBZ and 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ are the major circulating metabolites and are subsequently metabolized to sulfate or glucuronide conjugates. α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ are formed by carbonyl reductase that occurs mainly in the liver. α-HTBZ is O-dealkylated by CYP450 enzymes, principally CYP2D6, with some contribution of CYP1A2 to form 9-desmethyl-α-DHTBZ, a minor metabolite. β-HTBZ is O-dealkylated principally by CYP2D6 to form 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ.

The results of in vitro studies do not suggest that tetrabenazine, α-HTBZ, or β-HTBZ or 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ are likely to result in clinically significant inhibition of CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, or CYP3A. In vitro studies suggest that neither tetrabenazine nor its α- or β-HTBZ or 9-desmethyl-α- DHTBZ metabolites are likely to result in clinically significant induction of CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19.

Neither tetrabenazine nor its α- or β-HTBZ or 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ metabolites are likely to be a substrates or inhibitors of P-glycoprotein at clinically relevant concentrations in vivo.

Elimination

After oral administration, tetrabenazine is extensively hepatically metabolized, and the metabolites are primarily renally eliminated. α-HTBZ, β-HTBZ and 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ have half-lives of 7 hours, 5 hours and 12 hours respectively. In a mass balance study in 6 healthy volunteers, approximately 75% of the dose was excreted in the urine, and fecal recovery accounted for approximately 7 to 16% of the dose. Unchanged tetrabenazine has not been found in human urine. Urinary excretion of α-HTBZ or β-HTBZ accounted for less than 10% of the administered dose. Circulating metabolites, including sulfate and glucuronide conjugates of HTBZ metabolites as well as products of oxidative metabolism, account for the majority of metabolites in the urine.

Specific Populations

Hepatic Impairment

The disposition of tetrabenazine was compared in 12 patients with mild to moderate chronic liver impairment (Child-Pugh scores of 5-9) and 12 age- and gender-matched subjects with normal hepatic function who received a single 25 mg dose of tetrabenazine. In patients with hepatic impairment, tetrabenazine plasma concentrations were similar to or higher than concentrations of α-HTBZ, reflecting the markedly decreased metabolism of tetrabenazine to α-HTBZ. The mean tetrabenazine Cmax in subjects with hepatic impairment was approximately 7- to 190-fold higher than the detectable peak concentrations in healthy subjects. The elimination half-life of tetrabenazine in subjects with hepatic impairment was approximately 17.5 hours. The time to peak concentrations (tmax) of α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ was slightly delayed in subjects with hepatic impairment compared to age-matched controls (1.75 hrs vs. 1.0 hrs), and the elimination half-lives of the α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ were prolonged to approximately 10 and 8 hours, respectively. The exposure to α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ was approximately 30 to 39% greater in patients with liver impairment than in age-matched controls. The safety and efficacy of this increased exposure to tetrabenazine and other circulating metabolites are unknown so that it is not possible to adjust the dosage of tetrabenazine in hepatic impairment to ensure safe use. Therefore, tetrabenazine tablets are contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment [see Contraindications (4), Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Poor CYP2D6 Metabolizers

Although the pharmacokinetics of tetrabenazine tablets and its metabolites in patients who do not express the drug metabolizing enzyme, CYP2D6, poor metabolizers, (PMs), have not been systematically evaluated, it is likely that the exposure to α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ would be increased similar to that observed in patients taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (3- and 9-fold, respectively) [see Dosage and Administration (2.3), Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Use in Specific Populations (8.7)].

Drug Interactions

CYP2D6 Inhibitors

In vitro studies indicate that α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ are substrates for CYP2D6. The effect of CYP2D6 inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of tetrabenazine and its metabolites was studied in 25 healthy subjects following a single 50 mg dose of tetrabenazine given after 10 days of administration of the strong CYP2D6 inhibitor paroxetine 20 mg daily. There was an approximately 30% increase in Cmax and an approximately 3-fold increase in AUC for α-HTBZ in subjects given paroxetine prior to tetrabenazine compared to tetrabenazine given alone. For β-HTBZ, the Cmax and AUC were increased 2.4- and 9-fold, respectively, in subjects given paroxetine prior to tetrabenazine given alone. The elimination half-life of α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ was approximately 14 hours when tetrabenazine was given with paroxetine.

Strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, quinidine) markedly increase exposure to these metabolites. The effect of moderate or weak CYP2D6 inhibitors such as duloxetine, terbinafine, amiodarone, or sertraline on the exposure to tetrabenazine tablets and its metabolites has not been evaluated [see Dosage and Administration (2.3), Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Drug Interactions (7.1), Use in Specific Populations (8.7)].

Digoxin

Digoxin is a substrate for P-glycoprotein. A study in healthy volunteers showed that tetrabenazine tablets (25 mg twice daily for 3 days) did not affect the bioavailability of digoxin, suggesting that at this dose, tetrabenazine tablets does not affect P-glycoprotein in the intestinal tract. In vitro studies also do not suggest that tetrabenazine tablets or its metabolites are P-glycoprotein inhibitors.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

No increase in tumors was observed in p53+/- transgenic mice treated orally with tetrabenazine (5, 15, and 30 mg/kg/day) for 26 weeks.

No increase in tumors was observed in Tg.rasH2 transgenic mice treated orally with a major human metabolite, 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ (20, 100, and 200 mg/kg/day), for 26 weeks.

Mutagenesis

Tetrabenazine and metabolites α-HTBZ, β-HTBZ and 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ were negative in an in vitro bacterial reverse mutation assay. Tetrabenazine was clastogenic in an in vitro chromosomal aberration assay in Chinese hamster ovary cells in the presence of metabolic activation. α-HTBZ and β-HTBZ were clastogenic in an in vitro chromosome aberration assay in Chinese hamster lung cells in the presence and absence of metabolic activation. 9-desmethyl-β-DHTBZ was not clastogenic in an in vitro chromosomal aberration assays in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in the presence or absence of metabolic activation. In vivo micronucleus assay were conducted in male and female rats and male mice. Tetrabenazine was negative in male mice and rats but produced an equivocal response in female rats.

Impairment of Fertility

Oral administration of tetrabenazine (5, 15, or 30 mg/kg/day) to female rats prior to and throughout mating, and continuing through day 7 of gestation resulted in disrupted estrous cyclicity at doses greater than 5 mg/kg/day (less than the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

No effects on mating and fertility indices or sperm parameters (motility, count, density) were observed when males were treated orally with tetrabenazine (5, 15, or 30 mg/kg/day; up to 3 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) prior to and throughout mating with untreated females.

Because rats dosed with tetrabenazine do not produce 9-desmethyl-beta-DHTBZ, a major human metabolite, these studies may not have adequately assessed the potential of tetrabenazine tablets to impair fertility in

humans.

-

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

Study 1

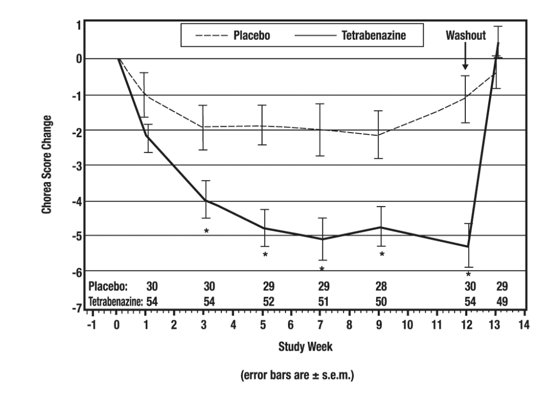

The efficacy of tetrabenazine tablets as a treatment for the chorea of Huntington’s disease was established primarily in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multi-center trial (Study 1) conducted in ambulatory patients with a diagnosis of HD. The diagnosis of HD was based on family history, neurological exam, and genetic testing. Treatment duration was 12 weeks, including a 7-week dose titration period and a 5-week maintenance period followed by a 1-week washout. Tetrabenazine tablets were started at a dose of 12.5 mg per day, followed by upward titration at weekly intervals, in 12.5 mg increments until satisfactory control of chorea was achieved, intolerable side effects occurred, or until a maximal dose of 100 mg per day was reached.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the Total Chorea Score, an item of the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS). On this scale, chorea is rated from 0 to 4 (with 0 representing no chorea) for 7 different parts of the body. The total score ranges from 0 to 28.

As shown in Figure 1, Total Chorea Scores for patients in the drug group declined by an estimated 5.0 units during maintenance therapy (average of Week 9 and Week 12 scores versus baseline), compared to an estimated 1.5 units in the placebo group. The treatment effect of 3.5 units was statistically significant. At the Week 13 follow-up in Study 1 (1 week after discontinuation of the study medication), the Total Chorea Scores of patients receiving tetrabenazine tablets returned to baseline.

Figure 1. Mean ± s.e.m. Changes from Baseline in Total Chorea Score in 84 HD Patients Treated with Tetrabenazine (n=54) or Placebo (n=30)

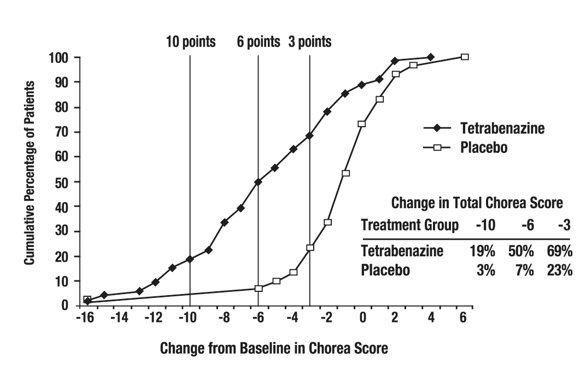

Figure 2 illustrates the cumulative percentages of patients from the tetrabenazine tablets and placebo treatment groups who achieved the level of reduction in the Total Chorea Score shown on the X axis. The left-ward shift of the curve (toward greater improvement) for the tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients indicates that these patients were more likely to have any given degree of improvement in chorea score. For example, about 7% of placebo patients had a 6-point or greater improvement compared to 50% of tetrabenazine tablets-treated patients. The percentage of patients achieving reductions of at least 10, 6, and 3 points from baseline to Week 12 are shown in the inset table.

Figure 2. Cumulative Percentage of Patients with Specified Changes from Baseline in Total Chorea Score. The Percentages of Randomized Patients within each treatment group who completed Study 1 were: Placebo 97%, Tetrabenazine 91%.

A Physician-rated Clinical Global Impression (CGI) favored tetrabenazine tablets statistically. In general, measures of functional capacity and cognition showed no difference between tetrabenazine tablets and placebo. However, one functional measure (Part 4 of the UHDRS), a 25-item scale assessing the capacity for patients to perform certain activities of daily living, showed a decrement for patients treated with tetrabenazine tablets compared to placebo, a difference that was nominally statistically significant. A 3-item cognitive battery specifically developed to assess cognitive function in patients with HD (Part 2 of the UHDRS) also showed a decrement for patients treated with tetrabenazine tablets compared to placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Study 2

A second controlled study was performed in patients who had been treated with open-label tetrabenazine tablets for at least 2 months (mean duration of treatment was 2 years). They were randomized to continuation of tetrabenazine tablets at the same dose (n=12) or to placebo (n=6) for three days, at which time their chorea scores were compared. Although the comparison did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1), the estimate of the treatment effect was similar to that seen in Study 1 (about 3.5 units).

-

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

16.1 How Supplied

Tetrabenazine tablets are available in the following strengths and packages:

The 12.5 mg tetrabenazine tablets are white, cylindrical, biplanar tablets with beveled edges, debossed ‘707’ on one side and plain on the other side.

Bottles of 112: NDC: 68094-905-10

The 25 mg tetrabenazine tablets are yellowish-buff, cylindrical, biplanar tablets with beveled edges, debossed ‘708’ on one side and scored on the other side.

Bottles of 112: NDC: 68094-805-10

-

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Advise the patient to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Medication Guide).

Risk of Suicidality

Inform patients and their families that tetrabenazine tablets may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behaviors. Counsel patients and their families to remain alert to the emergence of suicidal ideation and to report it immediately to the patient’s physician [see Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Risk of Depression

Inform patients and their families that tetrabenazine tablets may cause depression or may worsen preexisting depression. Encourage patients and their families to be alert to the emergence of sadness, worsening of depression, withdrawal, insomnia, irritability, hostility (aggressiveness), akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), anxiety, agitation, or panic attacks and to report such symptoms promptly to the patient’s physician [see Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Dosing of Tetrabenazine Tablets

Inform patients and their families that the dose of tetrabenazine tablets will be increased slowly to the dose that is best for each patient. Sedation, akathisia, parkinsonism, depression, and difficulty swallowing may occur. Such symptoms should be promptly reported to the physician, and the tetrabenazine tablets dose may need to be reduced or discontinued [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)].

Risk of Sedation and Somnolence

Inform patients that tetrabenazine tablets may induce sedation and somnolence and may impair the ability to perform tasks that require complex motor and mental skills. Advise patients that until they learn how they respond to tetrabenazine tablets, they should be careful doing activities that require them to be alert, such as driving a car or operating machinery [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

Interaction with Alcohol

Advise patients and their families that alcohol may potentiate the sedation induced by tetrabenazine tablets [see Drug Interactions (7.4)].

Usage in Pregnancy

Advise patients and their families to notify the physician if the patient becomes pregnant or intends to become pregnant during tetrabenazine tablets therapy, or is breastfeeding or intending to breastfeed an infant during therapy [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

Manufactured for:

Precision Dose, Inc.

722 Progressive Lane

South Beloit, IL 61080552701

Revised: 08/2023

-

Medication Guide

Tetrabenazine (TET ra BEN a Zeen) Tablets

Read the Medication Guide that comes with tetrabenazine tablets before you start taking it and each time you refill the prescription. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking with your doctor about your medical condition or your treatment. You should share this information with your family members and caregivers.

What is the most important information I should know about tetrabenazine tablets?

-

Tetrabenazine tablets can cause serious side effects, including:

- Depression

- suicidal thoughts

- suicidal actions

- You should not start taking tetrabenazine tablets if you are depressed (have untreated depression or depression that is not well controlled by medicine) or have suicidal thoughts.

- Pay close attention to any changes, especially sudden changes, in mood, behaviors, thoughts or feelings. This is especially important when tetrabenazine tablets are started and when the dose is changed.

Call the doctor right away if you become depressed or have any of the following symptoms, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you:

- feel sad or have crying spells

- lose interest in seeing your friends or doing things you used to enjoy

- sleep a lot more or a lot less than usual

- feel unimportant

- feel guilty

- feel hopeless or helpless

- more irritable, angry or aggressive than usual

- more or less hungry than usual or notice a big change in your body weight

- have trouble paying attention

- feel tired or sleepy all the time

- have thoughts about hurting yourself or ending your life

What are tetrabenazine tablets?

Tetrabenazine tablets are a medicine that is used to treat the involuntary movements (chorea) of Huntington’s disease. Tetrabenazine tablets do not cure the cause of the involuntary movements, and it does not treat other symptoms of Huntington’s disease, such as problems with thinking or emotions.

It is not known whether tetrabenazine tablets are safe and effective in children.

Who should not take tetrabenazine tablets?

Do not take tetrabenazine tablets if you:

- are depressed or have thoughts of suicide. See “What is the most important information I should know about tetrabenazine tablets?”

- have liver problems.

- are taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) medicine. Ask your doctor or pharmacist if you are not sure.

- are taking reserpine. Do not take medicines that contain reserpine (such as Serpalan® and Renese®-R) with tetrabenazine tablets. If your doctor plans to switch you from taking reserpine to tetrabenazine tablets, you must wait at least 20 days after your last dose of reserpine before you start taking tetrabenazine tablets.

What should I tell my doctor before taking tetrabenazine tablets?

Tell your doctor about all your medical conditions, including if you:

- have emotional or mental problems (for example, depression, nervousness, anxiety, anger, agitation, psychosis, previous suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts).

- have liver disease.

- have any allergies. See the end of this Medication Guide for a complete list of the ingredients in tetrabenazine tablets.

- have breast cancer or a history of breast cancer.

- have heart disease that is not stable, have heart failure or recently had a heart attack.

- have an irregular heartbeat (cardiac arrhythmia).

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. It is not known if tetrabenazine tablets can harm your unborn baby.

- are breastfeeding. It is not known if tetrabenazine passes into breast milk.

Tell your doctor about all the medicines you take, including prescription medicines and nonprescription medicines, vitamins and herbal products. Using tetrabenazine tablets with certain other medicines may cause serious side effects. Do not start any new medicines while taking tetrabenazine tablets without talking to your doctor first.

How should I take tetrabenazine tablets?

- Tetrabenazine tablets are tablets that you take by mouth.

- Take tetrabenazine tablets exactly as prescribed by your doctor.

- You may take tetrabenazine tablets with or without food.

- Your doctor will increase your dose of tetrabenazine tablets each week for several weeks, until you and your doctor find the best dose for you.

- If you stop taking tetrabenazine tablets or miss a dose, your involuntary movements may return or worsen in 12 to 18 hours after the last dose.

- Before starting tetrabenazine tablets, you should talk to your healthcare provider about what to do if you miss a dose. If you miss a dose and it is time for your next dose, do not double the dose.

- Tell your doctor if you stop taking tetrabenazine tablets for more than 5 days. Do not take another dose until you talk to your doctor.

- If your doctor thinks you need to take more than 50 mg of tetrabenazine tablets each day, you will need to have a blood test to see if it is safe for you.

What should I avoid while taking tetrabenazine tablets?

Sleepiness (sedation) is a common side effect of tetrabenazine tablets. While taking tetrabenazine tablets, do not drive a car or operate dangerous machinery until you know how tetrabenazine tablets affect you. Drinking alcohol and taking other drugs that may also cause sleepiness while you are taking tetrabenazine tablets may increase any sleepiness caused by tetrabenazine tablets.

What are the possible side effects of tetrabenazine tablets?

Tetrabenazine tablets can cause serious side effects, including:

- Depression, suicidal thoughts, or actions. See “What is the most important information I should know about tetrabenazine tablets?”

-

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS). Call your doctor right away and go to the nearest emergency room if you develop these signs and symptoms that do not have another obvious cause:

- high fever

- stiff muscles

- problems thinking

- very fast or uneven heartbeat

- increased sweating

- Parkinsonism. Symptoms of Parkinsonism include: slight shaking, body stiffness, trouble moving or keeping your balance.

- Restlessness. You may get a condition where you feel a strong urge to move. This is called akathisia.

- Irregular heartbeat. Tetrabenazine tablets increase your chance of having certain changes in the electrical activity in your heart which can be seen on an electrocardiogram (EKG). These changes can lead to a dangerous abnormal heartbeat. Taking tetrabenazine tablets with certain medicines may increase this chance.

- Dizziness due to blood pressure changes when you change position (orthostatic hypotension). Change positions slowly from lying down to sitting up and from sitting up to standing when taking tetrabenazine tablets. Tell your doctor right away if you get dizzy or faint while taking tetrabenazine tablets. Your doctor may need to watch your blood pressure closely.

Common side effects with tetrabenazine tablets include:

- sleepiness (sedation)

- trouble sleeping

- depression

- tiredness (fatigue)

- anxiety

- restlessness

- agitation

- nausea

Tell your doctor if you have any side effects. Do not stop taking tetrabenazine tablets without talking to your doctor first.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at 1-800-FDA-1088.

General information about tetrabenazine tablets

Tetrabenazine tablets contain the active ingredient tetrabenazine. They also contain these inactive ingredients: lactose, maize starch, talc, and magnesium stearate. The 25 mg tablets, which are pale yellow, also contain yellow iron oxide.

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use tetrabenazine tablets for a condition for which they were not prescribed. Do not give tetrabenazine tablets to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. They may harm them. Keep tetrabenazine tablets out of the reach of children.

This Medication Guide summarizes the most important information about tetrabenazine tablets. If you would like more information, talk with your doctor. You can ask your doctor or pharmacist for information about tetrabenazine tablets that is written for healthcare professionals.

You can also call Precision Dose, Inc. at 1-844-668-3942 or visit www.precisiondose.com.

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration.

Manufactured for:

Precision Dose, Inc.

722 Progressive Lane

South Beloit, IL 61080Trademarks are property of their respective owners.

Revised: 08/2023

-

Tetrabenazine tablets can cause serious side effects, including:

-

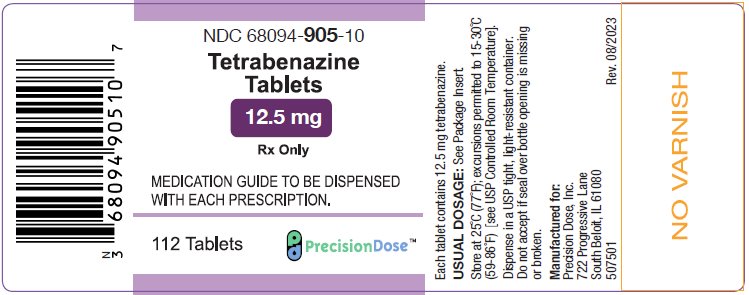

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL – 12.5 mg

NDC 68094-905-10

Tetrabenazine

Tablets12.5 mg

Rx only

MEDICATION GUIDE TO BE DISPENSED

WITH EACH PRESCRIPTION112 Tablets

PrecisionDose™

Each tablet contains 12.5 mg tetrabenazine.

USUAL DOSAGE: See Package Insert.

Store at 25°C (77°F); excursions permitted to 15-30°C

(59-86°F) [see USP Controlled Room Temperature].Dispense in a USP tight, light-resistant container.

Do not accept if seal over bottle opening is missing

or broken.Manufactured for:

Precision Dose, Inc.

722 Progressive Lane

South Beloit, IL 61080

507501 Rev.08/2023

-

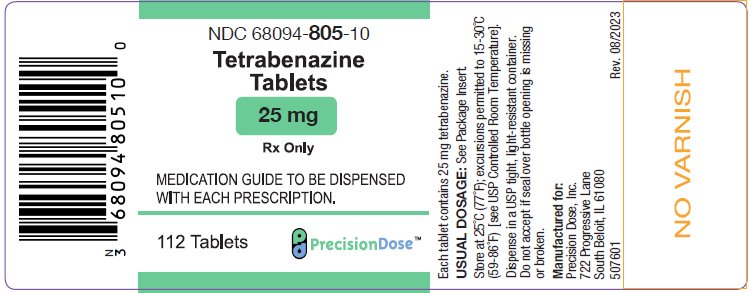

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL – 25 mg

NDC 68094-805-10

Tetrabenazine

Tablets25 mg

Rx only

MEDICATION GUIDE TO BE DISPENSED

WITH EACH PRESCRIPTION112 Tablets

PrecisionDose™

Each tablet contains 25 mg tetrabenazine.

USUAL DOSAGE: See Package Insert.

Store at 25°C (77°F); excursions permitted to 15-30°C

(59-86°F) [see USP Controlled Room Temperature].Dispense in a USP tight, light-resistant container.

Do not accept if seal over bottle opening is missing

or broken.Manufactured for:

Precision Dose, Inc.

722 Progressive Lane

South Beloit, IL 61080507601 Rev.

08/2023

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

TETRABENAZINE

tetrabenazine tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 68094-905 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength TETRABENAZINE (UNII: Z9O08YRN8O) (TETRABENAZINE - UNII:Z9O08YRN8O) TETRABENAZINE 12.5 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength LACTOSE, UNSPECIFIED FORM (UNII: J2B2A4N98G) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) STARCH, CORN (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) Product Characteristics Color WHITE Score no score Shape ROUND (cylindrical, biplanar) Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code 707 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 68094-905-10 112 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 12/01/2023 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA207682 12/01/2023 TETRABENAZINE

tetrabenazine tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 68094-805 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength TETRABENAZINE (UNII: Z9O08YRN8O) (TETRABENAZINE - UNII:Z9O08YRN8O) TETRABENAZINE 25 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength LACTOSE, UNSPECIFIED FORM (UNII: J2B2A4N98G) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) STARCH, CORN (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) FERRIC OXIDE YELLOW (UNII: EX438O2MRT) Product Characteristics Color YELLOW (yellowish-buff) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND (cylindrical, biplanar) Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code 708 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 68094-805-10 112 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 12/01/2023 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA207682 12/01/2023 Labeler - Precision Dose Inc. (035886746)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.