OPIPZA- aripiprazole film, soluble

OPIPZA by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

OPIPZA by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Carwin Pharmaceutical Associates, LLC, Xiamen LP Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use OPIPZA safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for OPIPZA.

OPIPZA (aripiprazole) oral film

Initial U.S. Approval: 2002WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS and SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.

- Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. OPIPZA is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. (5.1)

- Increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in pediatric and young adult patients taking antidepressants. Closely monitor all antidepressant-treated patients for clinical worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. (5.3)

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

OPIPZA is an atypical antipsychotic indicated for:

- treatment of schizophrenia in patients ages 13 years and older (1)

- adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults (1)

- irritability associated with autistic disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older (1)

- treatment of Tourette's disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older (1)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Initial Starting Dosage Recommended Dosage Maximum Dosage Schizophrenia (adults) (2.1) 10 to 15 mg/day 10 to 15 mg/day 30 mg/day Schizophrenia – (pediatric patients 13 years and older) (2.1) 2 mg/day 10 mg/day 30 mg/day Adjunctive Treatment of MDD (adults) (2.2) 2 to 5 mg/day 5 to 10 mg/day 15 mg/day Irritability associated with autistic disorder (pediatric patients 6 years and older) (2.3) 2 mg/day 5 to 10 mg/day 15 mg/day Tourette's disorder (pediatric patients 6 years and older) (2.4) < 50 kg 2 mg/day 5 mg/day 10 mg/day ≥ 50 kg 2 mg/day 10 mg/day 20 mg/day DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- Oral Film: 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Known hypersensitivity to aripiprazole (4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis: Increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack, including fatalities) (5.2)

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Manage with immediate discontinuation and close monitoring (5.4)

- Tardive Dyskinesia: Discontinue if clinically appropriate (5.5)

- Metabolic Changes: Monitor for hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and weight gain (5.6)

- Pathological Gambling and Other Compulsive Behaviors: Consider dose reduction or discontinuation (5.7)

- Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope: Monitor heart rate and blood pressure and caution patients with known cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, and risk of dehydration or syncope (5.8)

- Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis: Perform complete blood cell counts (CBC) in patients with a history of a clinically significant low white blood cell count (WBC) or a history of leukopenia or neutropenia. Consider discontinuing OPIPZA if clinically significant decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors (5.10)

- Seizures: Use cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower the seizure threshold (5.11)

- Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment: Use caution when operating machinery (5.12)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice that for placebo) were (6.1):

- Schizophrenia (adults): akathisia

- Schizophrenia (pediatric patients 13 to 17 years): extrapyramidal disorder, somnolence, and tremor

- Adjunctive treatment of MDD (adults): akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and blurred vision

- Irritability associated with autistic disorder (pediatric 6 years and older): sedation, fatigue, vomiting, somnolence, tremor, pyrexia, drooling, decreased appetite, salivary hypersecretion, extrapyramidal disorder, and lethargy

- Tourette's disorder (pediatric patients 6 years and older): sedation, somnolence, nausea, headache, nasopharyngitis, fatigue, increased appetite

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Carwin Pharmaceutical Associates at 1-877-676-0778 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Dosage adjustments for patients taking CYP2D6 inhibitors, CYP3A4 inhibitors, or CYP3A4 inducers (7.1):

Factors Dosage Recommendations CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (7.1) Administer a quarter of recommended dosage (2.6) Strong CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 inhibitors (7.1) Administer half of recommended dosage (2.6) Strong CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 inhibitors (7.1) Administer a quarter of recommended dosage (2.6) Strong CYP3A4 inducers (7.1) Double the recommended dosage over 1 to 2 weeks (2.6) USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

Pregnancy: May cause extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms in neonates with third trimester exposure (8.1)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 8/2024

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIARELATED PSYCHOSIS and SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Schizophrenia in Patients 13 Years and Older

2.2 Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults

2.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder in Pediatric Patients 6 years and Older

2.4 Tourette's Disorder in Pediatric Patients 6 years and Older

2.5 Important Administration Information

2.6 Dosage Recommendations and Modifications for Cytochrome P450 Considerations

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

5.2 Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

5.3 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Adolescents and Young Adults

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

5.5 Tardive Dyskinesia

5.6 Metabolic Changes

5.7 Pathological Gambling and Other Compulsive Behaviors

5.8 Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

5.9 Falls

5.10 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

5.11 Seizures

5.12 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

5.13 Body Temperature Regulation

5.14 Dysphagia

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Drugs Having Clinically Important Interactions with OPIPZA

7.2 Drugs Having No Clinically Important Interactions with OPIPZA

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers

8.7 Renal Impairment

8.8 Hepatic Impairment

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Overview of the Clinical Studies

14.2 Schizophrenia

14.3 Adjunctive Treatment of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder

14.4 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder

14.5 Tourette's Disorder

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIARELATED PSYCHOSIS and SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.

OPIPZA is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in pediatric and young adult patients in shortterm studies. Closely monitor all antidepressant-treated patients for clinical worsening, and for emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

OPIPZA is indicated for the:

- treatment of schizophrenia in patients ages 13 years and older

- adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults

- treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older

- treatment of Tourette's disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Schizophrenia in Patients 13 Years and Older

Adults

The recommended starting and target dosage of OPIPZA for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults is 10 mg or 15 mg once daily. Aripiprazole has been systematically evaluated and shown to be effective in a dose range of 10 mg to 30 mg per day; however, doses higher than 10 mg or 15 mg per day were not more effective than 10 mg or 15 mg per day. Dosage increases should generally not be made before 2 weeks, the time needed to achieve steady-state [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Pediatric Patients Ages 13 Years and Older

The recommended starting dosage of OPIPZA for the treatment of schizophrenia in pediatric patients 13 years and older is 2 mg once daily. The recommended target dosage of OPIPZA is 10 mg once daily. Aripiprazole was studied in pediatric patients 13 to 17 years of age with schizophrenia at daily dosages of 10 mg and 30 mg. The starting daily dosage in these patients was 2 mg, which was titrated to 5 mg after 2 days and to the target dose of 10 mg after 2 additional days. Subsequent dose increases should be administered in 5 mg increments. The 30 mg per day dosage was not shown to be more efficacious than the 10 mg per day dosage.

2.2 Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults

The recommended starting dosage for OPIPZA as adjunctive treatment of MDD in adults already taking an antidepressant is 2 mg to 5 mg once daily. The recommended dosage range is 2 mg to 15 mg once daily. Dosage adjustments of up to 5 mg per day should occur gradually, at intervals of no less than one week [see Clinical Studies (14.3)]. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the continued need for maintenance treatment.

2.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder in Pediatric Patients 6 years and Older

The recommended dosage range for the treatment of pediatric patients 6 to 17 years with irritability associated with autistic disorder is 5 mg to 15 mg once daily.

Dosing should be initiated at 2 mg once daily. The dose should be increased to 5 mg per day, with subsequent increases to 10 mg or 15 mg per day if needed. Dose adjustments of up to 5 mg per day should occur gradually, at intervals of no less than one week [see Clinical Studies (14.4)]. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the continued need for maintenance treatment.

2.4 Tourette's Disorder in Pediatric Patients 6 years and Older

The recommended dosage range for treatment of Tourette's disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older is 5 mg to 20 mg once daily.

For patients weighing less than 50 kg, dosage should be initiated at 2 mg once daily with a target dosage of 5 mg once daily after 2 days. The dosage can be increased to 10 mg once daily in patients who do not achieve optimal control of tics. Dosage adjustments should occur gradually at intervals of no less than one week.

For patients weighing 50 kg or more, dosing should be initiated at 2 mg once daily for 2 days, and then increased to 5 mg once daily for 5 days, with a target dosage of 10 mg once daily on Day 8. The dosage can be increased up to 20 mg once daily for patients who do not achieve optimal control of tics. Dosage adjustments should occur gradually in increments of 5 mg per day at intervals of no less than one week [see Clinical Studies (14.5)].

Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the continued need for maintenance treatment.

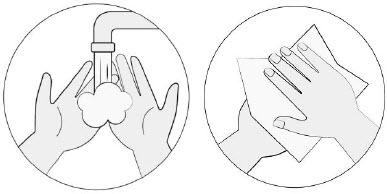

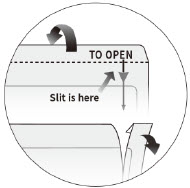

2.5 Important Administration Information

Instruct patients and/or caregivers to read the "Instruction for Use" carefully for complete directions on how to properly dose and administer OPIPZA.

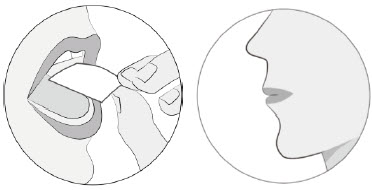

Administer OPIPZA orally with or without food [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Apply OPIPZA on top of the tongue where it dissolves in saliva and can be swallowed in a normal manner without the need for water or other liquids.

The patient should refrain from chewing the film and should not swallow an undissolved film. Do not cut or split OPIPZA.

Administer only one oral film at a time. If an additional film is needed to complete the dosage, administer after the previous film has completely dissolved.

2.6 Dosage Recommendations and Modifications for Cytochrome P450 Considerations

Dosage recommendations and modifications for patients who are known CYP2D6 poor metabolizers and/or in patients taking concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitors, CYP2D6 inhibitors, or strong CYP3A4 inducers are described in Table 1.

When the coadministered drug is withdrawn from the combination therapy, Aripiprazole Oral Film dosage should be adjusted to its previous dose. When the coadministered CYP3A4 inducer is withdrawn, Aripiprazole Oral Film dosage should be reduced to the previous dose over 1 to 2 weeks. Patients receiving a combination of strong, moderate, and weak inhibitors of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 (e.g., a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor and a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor or a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor with a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor), the dosing may be reduced to one-quarter (25%) of the recommended dose initially and then adjusted to achieve clinical response [see Dosage and Administration (2.5)].

Table 1: Dosage Recommendations and Modifications for OPIPZA in Patients Who are Known CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers and in Patients Taking Concomitant CYP2D6 Inhibitors and/or 3A4 Inhibitors, CYP3A4 Inducers Patient Population Dosage Recommendations and Modifications for OPIPZA CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers Known CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers Administer half of the recommended dose Known CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizers taking concomitant strong CYP3A4 inhibitors Administer a quarter of the recommended dose Patients Taking OPIPZA with CYP2D6 Inhibitors and/or CYP3A4 Inhibitors, CYP3A4 Inducers Concomitant use of OPIPZA with strong CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 inhibitors Administer half of the recommended dose Concomitant use of OPIPZA with strong CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 inhibitors Administer a quarter of the recommended dose Concomitant use of OPIPZA with strong CYP3A4 inducers Double the recommended dose over 1 to 2 weeks When adjunctive OPIPZA is administered to patients with major depressive disorder, OPIPZA should be administered without dosage adjustment as specified in Dosage and Administration (2.2).

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

OPIPZA is contraindicated in patients with a history of a hypersensitivity to aripiprazole. Hypersensitivity reactions ranging from pruritus/urticaria to anaphylaxis have been reported in patients receiving aripiprazole [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of 17 placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group.

Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear.

OPIPZA is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

5.2 Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

In placebo-controlled clinical studies (two flexible dose and one fixed dose study) of dementia-related psychosis, there was an increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack), including fatalities, in aripiprazole-treated patients (mean age: 84 years; range: 78 to 88 years). In the fixed-dose study, there was a statistically significant dose response relationship for cerebrovascular adverse reactions in patients treated with aripiprazole. OPIPZA is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

5.3 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Adolescents and Young Adults

In pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and other antidepressant classes) that included approximately 77,000 adult patients and 4,500 pediatric patients, the incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in antidepressant-treated patients age 24 years and younger was greater than in placebo-treated patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among drugs, but there was an increased risk identified in young patients for most drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors across the different indications, with the highest incidence in patients with MDD. The drug-placebo differences in the number of cases of suicidal thoughts and behaviors per 1,000 patients treated are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Risk Differences of the Number of Patients of Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior in the Pooled Placebo-Controlled Trials of Antidepressants in Pediatric* and Adult Patients Age Range Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Patients of Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors per 1,000 Patients Treated* - * OPIPZA is not approved in pediatric patients with MDD.

Increases Compared to Placebo <18 years old 14 additional patients 18 to 24 years old 5 additional patients Decreases Compared to Placebo 25 to 64 years old 1 fewer patient ≥65 years old 6 fewer patient It is unknown whether the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children, adolescents, and young adults extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond four months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with MDD that antidepressants delay the recurrence of depression and that depression itself is a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Monitor all antidepressant-treated patients for any indication for clinical worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, especially during the initial few months of drug therapy, and at times of dosage changes. Counsel family members or caregivers of patients to monitor for changes in behavior and to alert the healthcare provider. Consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing OPIPZA, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidal thoughts or behaviors. It should be noted that OPIPZA is not approved for use in treating depression in the pediatric population.

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal symptom complex has been reported with antipsychotic drugs, including aripiprazole. Rare cases of NMS have been reported during aripiprazole treatment in the global clinical database.

Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure.

If NMS is suspected, immediately discontinue OPIPZA and provide symptomatic treatment and monitoring.

5.5 Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia, a syndrome of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements may develop in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to predict which patients will develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible appear to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose increases. However, the syndrome can develop after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses. It may also occur after discontinuation of treatment.

Tardive dyskinesia may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is discontinued. Antipsychotic treatment, itself may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome and may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, OPIPZA should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who suffer from a chronic illness that (1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs and (2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient treated with OPIPZA, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment with OPIPZA despite the presence of the syndrome.

5.6 Metabolic Changes

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that include hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and body weight gain. While all drugs in the class have been shown to produce some metabolic changes, each drug has its own specific risk profile.

Hyperglycemia/Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia, in some cases extreme and associated with diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, have been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. There have been reports of hyperglycemia in patients treated with aripiprazole [see Adverse Reactions (6.1, 6.2)]. Assessment of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and glucose abnormalities is complicated by the possibility of an increased background risk of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia and the increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus in the general population. Given these confounders, the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and hyperglycemia-related adverse events is not completely understood. However, epidemiological studies suggest an increased risk of hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions in patients treated with the atypical antipsychotics.

Patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics, including OPIPZA, should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of anti-diabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the atypical antipsychotic drug.

Adults

In an analysis of 13 placebo-controlled monotherapy trials in adults, primarily with schizophrenia or another indication, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients (+4.4 mg/dL; median exposure 25 days; N=1,057) was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients (+2.5 mg/dL; median exposure 22 days; N=799). Table 3 shows the proportion of aripiprazole-treated patients with normal and borderline fasting glucose at baseline (median exposure 25 days) that had high fasting glucose measurements compared to placebo-treated patients (median exposure 22 days).

Table 3: Changes in Fasting Glucose from Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trials in Adults Category Change (at least once) from Baseline Treatment Arm n/N % Fasting Glucose Normal to High

(<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 31/822 3.8 Placebo 22/605 3.6 Borderline to High

(≥100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 31/176 17.6 Placebo 13/142 9.2 At 24 weeks, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients [+2.2 mg/dL (n=42) and +9.6 mg/dL (n=28), respectively].

The mean change in fasting glucose in adjunctive trials of aripiprazole-treated patients with major depressive disorder (+0.7 mg/dL; median exposure 42 days; N=241) was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients (+0.8 mg/dL; median exposure 42 days; N=246). Table 4 shows the proportion of adult patients with changes in fasting glucose levels from two placebo-controlled, adjunctive trials (median exposure 42 days) in patients with major depressive disorder.

Table 4: Changes in Fasting Glucose from Placebo-Controlled Adjunctive Trials in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder Category Change (at least once) from Baseline Treatment Arm n/N % Fasting Glucose Normal to High

(<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 2/201 1.0 Placebo 2/204 1.0 Borderline to High

(≥100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 4/34 11.8 Placebo 3/37 8.1 Pediatric Patients 13 Years and Older

In an analysis of two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients 13 to 17 years with schizophrenia and pediatric patients 10 to 17 years with another indication, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients (+4.8 mg/dL; with a median exposure of 43 days; N=259) was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients (+1.7 mg/dL; with a median exposure of 42 days; N=123).

In an analysis of two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients 6 to 17 years with irritability associated with autistic disorder (6 to 17 years) with median exposure of 56 days, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients (–0.2 mg/dL; N=83) was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients (–0.6 mg/dL; N=33).

In an analysis of two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients 6 to 18 years with Tourette's disorder with median exposure of 57 days, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients (0.79 mg/dL; N=90) was not significantly different than in placebo-treated patients (–1.66 mg/dL; N=58).

Table 5 shows the proportion of patients with changes in fasting glucose levels from the pooled pediatric patients (13 to 17 years) with schizophrenia and pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) with another indication (median exposure of 42 to 43 days), from two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) with irritability associated with autistic disorder (median exposure of 56 days), and from the two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) with Tourette's disorder (median exposure 57 days).

Table 5: Changes in Fasting Glucose from Placebo-Controlled Trials in Pediatric Patients 6 to 17 Years Category Change (at least once) from Baseline Indication Treatment Arm n/N % Fasting Glucose

Normal to High

(<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Pooled Schizophrenia and another indication Aripiprazole 2/236 0.8 Placebo 2/110 1.8 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder Aripiprazole 0/73 0 Placebo 0/32 0 Tourette's Disorder Aripiprazole 3/88 3.4 Placebo 1/58 1.7 Fasting Glucose

Borderline to High

(≥100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)Pooled Schizophrenia and another indication Aripiprazole 1/22 4.5 Placebo 0/12 0 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder Aripiprazole 0/9 0 Placebo 0/1 0 Tourette's Disorder Aripiprazole 0/11 0 Placebo 0/4 0 In the pooled trials that enrolled pediatric patients 13 to 17 years with schizophrenia and another indication, the mean change in fasting glucose in aripiprazole-treated patients at 12 weeks was not significantly different than in placebotreated patients [+2.4 mg/dL (n=81) and +0.1 mg/dL (n=15), respectively].

Dyslipidemia

Undesirable alterations in lipids have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.

There were no significant differences between aripiprazole-treated patients and patients treated with placebo in the proportion with changes from normal to clinically significant levels for fasting/nonfasting total cholesterol, fasting triglycerides, fasting LDLs, and fasting/nonfasting HDLs. Analyses of patients with at least 12 or 24 weeks of exposure were limited by small numbers of patients.

Adults

Table 6 shows the proportion of adult patients, primarily from pooled schizophrenia and another indication monotherapy placebo-controlled trials, with changes in total cholesterol (pooled from 17 trials; median exposure 21 to 25 days), fasting triglycerides (pooled from eight trials; median exposure 42 days), fasting LDL cholesterol (pooled from eight trials; median exposure 39 to 45 days, except for placebo-treated patients with baseline normal fasting LDL measurements, who had median treatment exposure of 24 days) and HDL cholesterol (pooled from nine trials; median exposure 40 to 42 days).

Table 6: Changes in Blood Lipid Parameters from Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trials in Adults Treatment Arm n/N % Total Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 34/1,357 2.5 Placebo 27/973 2.8 Fasting Triglycerides

Normal to High

(<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 40/539 7.4 Placebo 30/431 7.0 Fasting LDL Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<100 mg/dL to ≥160 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 2/332 0.6 Placebo 2/268 0.7 HDL Cholesterol

Normal to Low

(≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 121/1,066 11.4 Placebo 99/794 12.5 In monotherapy trials in adults, the proportion of patients at 12 weeks and 24 weeks with changes from Normal to High in total cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), fasting triglycerides, and fasting LDL cholesterol were similar between aripiprazole - and placebo-treated patients: at 12 weeks, Total Cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), 1/71 (1.4%) vs. 3/74 (4.1%); Fasting Triglycerides, 8/62 (12.9%) vs. 5/37 (13.5%); Fasting LDL Cholesterol, 0/34 (0%) vs. 1/25 (4.0%), respectively; and at 24 weeks, Total Cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), 1/42 (2.4%) vs. 3/37 (8.1%); Fasting Triglycerides, 5/34 (14.7%) vs. 5/20 (25%); Fasting LDL Cholesterol, 0/22 (0%) vs. 1/18 (5.6%), respectively.

Table 7 shows the proportion of patients with changes in total cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), fasting triglycerides, fasting LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol from two placebo-controlled adjunctive trials in adults with major depressive disorder (median exposure 42 days).

Table 7: Changes in Blood Lipid Parameters from Placebo-Controlled Adjunctive Trials in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder Treatment Arm n/N % Total Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 3/139 2.2 Placebo 7/135 5.2 Fasting Triglycerides

Normal to High

(<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 14/145 9.7 Placebo 6/147 4.1 Fasting LDL Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<100 mg/dL to ≥160 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 0/54 0 Placebo 0/73 0 HDL Cholesterol

Normal to Low

(≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 17/318 5.3 Placebo 10/286 3.5 Pediatric Patients 10 to 17 Years

Table 8 shows the proportion of pediatric patients (13 to 17 years) with schizophrenia and pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) with another indication with changes in total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol (pooled from two placebo-controlled trials; median exposure 42 to 43 days) and fasting triglycerides (pooled from two placebo-controlled trials; median exposure 42 to 44 days).

Table 8: Changes in Blood Lipid Parameters from Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trials in Pediatric Patients 10 to 17 Years with Schizophrenia and another Indication Treatment Arm n/N % Total Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<170 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 3/220 1.4 Placebo 0/116 0 Fasting Triglycerides

Normal to High

(<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 7/187 3.7 Placebo 4/85 4.7 HDL Cholesterol

Normal to Low

(≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 27/236 11.4 Placebo 22/109 20.2 In monotherapy trials of pediatric patients with schizophrenia and pediatric patients with another indication, the proportion of patients at 12 weeks and 24 weeks with changes from Normal to High in total cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), fasting triglycerides, and fasting LDL cholesterol were similar between aripiprazole- and placebotreated patients: at 12 weeks, Total Cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), 0/57 (0%) vs. 0/15 (0%); Fasting Triglycerides, 2/72 (2.8%) vs. 1/14 (7.1%), respectively; and at 24 weeks, Total Cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting), 0/36 (0%) vs. 0/12 (0%); Fasting Triglycerides, 1/47 (2.1%) vs. 1/10 (10.0%), respectively.

Table 9 shows the proportion of patients with changes in total cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting) and fasting triglycerides (median exposure 56 days) and HDL cholesterol (median exposure 55 to 56 days) from two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) with irritability associated with autistic disorder.

Table 9: Changes in Blood Lipid Parameters from Placebo-Controlled Trials in Pediatric Patients 6 to 17 Years with Autistic Disorder Treatment Arm n/N % Total Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<170 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 1/95 1.1 Placebo 0/34 0 Fasting Triglycerides

Normal to High

(<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 0/75 0 Placebo 0/30 0 HDL Cholesterol

Normal to Low

(≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 9/107 8.4 Placebo 5/49 10.2 Table 10 shows the proportion of patients with changes in total cholesterol (fasting/nonfasting) and fasting triglycerides (median exposure 57 days) and HDL cholesterol (median exposure 57 days) from two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) with Tourette's disorder.

Table 10: Changes in Blood Lipid Parameters from Placebo-Controlled Trials in Pediatric Patients 6 to 18 Years with Tourette's Disorder Treatment Arm n/N % Total Cholesterol

Normal to High

(<170 mg/dL to ⩾200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 1/85 1.2 Placebo 0/46 0 Fasting Triglycerides

Normal to High

(<150 mg/dL to ⩾200 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 5/94 5.3 Placebo 2/55 3.6 HDL Cholesterol

Normal to Low

(⩾40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL)Aripiprazole 4/108 3.7 Placebo 2/67 3.0 Weight Gain

Weight gain has been observed with atypical antipsychotic use. Clinical monitoring of weight is recommended.

Adults

In an analysis of 13 placebo-controlled monotherapy trials, primarily from pooled schizophrenia and another indication, with a median exposure of 21 to 25 days, the mean change in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was +0.3 kg (N=1673) compared to -0.1 kg (N=1100) in placebo-controlled patients. At 24 weeks, the mean change from baseline in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was -1.5 kg (n=73) compared to -0.2 kg (n=46) in patients treated with placebo patients.

In the trials adding aripiprazole to antidepressants, patients first received 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment followed by 6 weeks of adjunctive aripiprazole or placebo in addition to their ongoing antidepressant treatment. The mean change in body weight in patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole was +1.7 kg (N=347) compared to +0.4 kg (N=330) in patients receiving adjunctive placebo.

Table 11 shows the percentage of adult patients with weight gain ≥7% of body weight by indication.

Table 11: Percentage of Patients from Placebo-Controlled Trials in Adults with Weight Gain ≥7% of Body Weight Indication Treatment Arm N Patients

n (%)- * 4 to 6 weeks duration;

- † 3 weeks duration;

- ‡ 6 weeks duration.

Weight gain ≥7% of body weight Schizophrenia* Aripiprazole 852 69 (8.1) Placebo 379 12 (3.2) Another indication† Aripiprazole 719 16 (2.2) Placebo 598 16 (2.7) Major Depressive Disorder

(Adjunctive Therapy)‡Aripiprazole 347 18 (5.2) Placebo 330 2 (0.6) Pediatric Patients 6 to 17 Years

In an analysis of two placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients 13 to 17 years with schizophrenia and pediatric patients 10 to 17 years with another indication with median exposure of 42 to 43 days, the mean change in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was +1.6 kg (N=381) compared to +0.3 kg (N=187) in placebo-treated patients. At 24 weeks, the mean change from baseline in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was +5.8 kg (n=62) compared to +1.4 kg (n=13) in patients treated with placebo.

In two short-term, placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) with irritability associated with autistic disorder with median exposure of 56 days, the mean change in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was +1.6 kg (n=209) compared to +0.4 kg (n=98) in pediatric patients treated with placebo.

In two short-term, placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients 6 to 18 years with Tourette's disorder with median exposure of 57 days, the mean change in body weight in aripiprazole-treated patients was +1.5 kg (n=105) compared to +0.4 kg (n=66) in patients treated with placebo.

Table 12 shows the percentage of pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) with weight gain ≥7% of body weight by indication.

Table 12: Percentage of Patients from Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trials in Pediatric Patients 6 to 17 Years with Weight Gain ≥7% of Body Weight Indication Treatment Arm N Patients

n (%)- * 4 to 6 weeks duration;

- † 8 weeks duration;

- ‡ 8 to 10 weeks duration.

Weight gain ≥7% of body weight Pooled Schizophrenia and another indication* Aripiprazole 381 20 (5.2) Placebo 187 3 (1.6) Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder† Aripiprazole 209 55 (26.3) Placebo 98 7 (7.1) Tourette's Disorder‡ Aripiprazole 105 21 (20.0) Placebo 66 5 (7.6) In an open-label trial that enrolled patients from the two placebo-controlled trials of pediatric patients 13 to 17 years with schizophrenia and pediatric patients 10 to 17 years with another indication, 73.2% of patients (238/325) completed 26 weeks of therapy with aripiprazole. After 26 weeks, 32.8% of patients gained ≥7% of their body weight, not adjusted for normal growth. To adjust for normal growth, z-scores were derived (measured in standard deviations [SD]), which normalize for the natural growth of pediatric patients and adolescents by comparisons to age- and gender-matched population standards. A z-score change <0.5 SD is considered not clinically significant. After 26 weeks, the mean change in z-score was 0.09 SD.

In an open-label trial that enrolled patients from two short-term, placebo-controlled trials, pediatric patients 6 to 17 years with irritability associated with autistic disorder, as well as de novo patients, 60.3% (199/330) completed one year of therapy with aripiprazole. The mean change in weight z-score was 0.26 SDs for patients receiving >9 months of treatment.

When treating pediatric patients for any indication, weight gain should be monitored and assessed against that expected for normal growth.

5.7 Pathological Gambling and Other Compulsive Behaviors

Post-marketing case reports suggest that patients can experience intense urges, particularly for gambling, and the inability to control these urges while taking aripiprazole. Other compulsive urges, reported less frequently, include sexual urges, shopping, eating or binge eating, and other impulsive or compulsive behaviors. Because patients may not recognize these behaviors as abnormal, it is important for prescribers to ask patients or their caregivers specifically about the development of new or intense gambling urges, compulsive sexual urges, compulsive shopping, binge or compulsive eating, or other urges while being treated with aripiprazole. It should be noted that impulse-control symptoms can be associated with the underlying disorder. In some cases, although not all, urges were reported to have stopped when the dose was reduced, or the medication was discontinued. Compulsive behaviors may result in harm to the patient and others if not recognized. Consider dose reduction or stopping the medication if a patient develops such urges.

5.8 Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

OPIPZA may cause orthostatic hypotension, perhaps due to its α1-adrenergic receptor antagonism. The incidence of orthostatic hypotension-associated events from short-term, placebo-controlled trials of adult patients treated with another oral aripiprazole product (n=2,467) included (aripiprazole incidence, placebo incidence) orthostatic hypotension (1%, 0.3%), postural dizziness (0.5%, 0.3%), and syncope (0.5%, 0.4%); of pediatric patients 6 to 18 years of age (n=732) on another oral aripiprazole product included orthostatic hypotension (0.5%, 0%), postural dizziness (0.4%, 0%), and syncope (0.2%, 0%) [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

The incidence of a significant orthostatic change in blood pressure (defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥20 mmHg accompanied by an increase in heart rate ≥25 bpm when comparing standing to supine values) for another oral aripiprazole product was not meaningfully different from placebo (aripiprazole incidence, placebo incidence): in adults treated with another oral aripiprazole product (4%, 2%), in pediatric patients treated with another oral aripiprazole-product aged 6 to 18 years (0.4%, 1%).

Use OPIPZA with caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease, heart failure or conduction abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease, or conditions which would predispose patients to hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, and treatment with antihypertensive medications) [see Drug Interactions (7.1)]. Monitoring of orthostatic vital signs should be considered in patients who are vulnerable to hypotension.

5.9 Falls

Antipsychotics, including OPIPZA, may cause somnolence, postural hypotension, motor and sensory instability, which may lead to falls and, consequently, fractures or other injuries. For patients with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate these effects, complete fall risk assessments when initiating antipsychotic treatment and recurrently for patients on long-term antipsychotic therapy.

5.10 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

In clinical trials and/or postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia and neutropenia have been reported temporally related to antipsychotic agents, including aripiprazole. Agranulocytosis has also been reported.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC)/absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and history of drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia. In patients with a history of a clinically significant low WBC/ANC or drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia, perform a complete blood count (CBC) frequently during the first few months of therapy. In such patients, consider discontinuation of OPIPZA at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors.

Monitor patients with clinically significant neutropenia for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treat promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Discontinue OPIPZA in patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1,000/mm3) and follow their WBC counts until recovery.

5.11 Seizures

In short-term, placebo-controlled trials, patients with a history of seizures excluded seizures/convulsions occurred in 0.1% (3/2,467) of undiagnosed adult patients and in 0.1% (1/732) of pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) treated with another oral aripiprazole product.

As with other antipsychotic drugs, use OPIPZA cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower the seizure threshold. Conditions that lower the seizure threshold may be more prevalent in a population of 65 years or older.

5.12 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

OPIPZA, like other antipsychotics, may have the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills. For example, in short-term, placebo-controlled trials of another oral aripiprazole product, somnolence (including sedation) was reported as follows (aripiprazole incidence, placebo incidence): in adult patients (n=2,467) treated with oral aripiprazole (11%, 6%), in pediatric patients ages 6 to 17 years (n=611) (24%, 6%). Somnolence (including sedation) led to discontinuation in 0.3% (8/2,467) of adult patients and 3% (20/732) of pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) on oral aripiprazole in short-term, placebo-controlled trials.

Patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery or operating a motor vehicle, until they are reasonably certain that therapy with OPIPZA does not affect them adversely.

5.13 Body Temperature Regulation

Disruption of the body's ability to reduce core body temperature has been attributed to antipsychotic agents. Appropriate care is advised when prescribing OPIPZA for patients who will be experiencing conditions which may contribute to an elevation in core body temperature, (e.g., exercising strenuously, exposure to extreme heat, receiving concomitant medication with anticholinergic activity, or being subject to dehydration) [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)].

5.14 Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use, including aripiprazole. OPIPZA and other antipsychotic drugs should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1) and Adverse Reactions (6.2)].

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions are discussed in more detail in other sections of the labeling:

- Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Tardive Dyskinesia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Metabolic Changes [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Pathological Gambling and Other Compulsive Behaviors [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Orthostatic Hypotension [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Falls [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

- Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.10)]

- Seizures [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]

- Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)]

- Body Temperature Regulation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)]

- Dysphagia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

The safety of OPIPZA for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia in patients 13 years and older, adjunctive treatment of adults with MDD, treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older, and treatment of Tourette's disorder in pediatric patients 6 years and older is based on adequate and well-controlled studies of another oral aripiprazole product. Below is a display of adverse reactions of oral aripiprazole (referred to as "aripiprazole" in this section) from those adequate and well-controlled studies.

Aripiprazole has been evaluated for safety in 13,543 adult patients who participated in multiple-dose, clinical trials in schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and other indications, and who had approximately 7,619 patient-years of exposure to oral aripiprazole. A total of 3,390 patients were treated with oral aripiprazole for at least 180 days and 1,933 patients treated with oral aripiprazole had at least one year of exposure.

Aripiprazole has been evaluated for safety in 1,686 pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) who participated in multiple-dose, clinical trials in schizophrenia, autistic disorder, Tourette's disorder or other indications who had approximately 1,342 patient-years of exposure to oral aripiprazole. A total of 959 pediatric patients were treated with oral aripiprazole for at least 180 days and 556 pediatric patients treated with oral aripiprazole had at least one year of exposure.

The conditions and duration of treatment with aripiprazole (monotherapy and adjunctive therapy with antidepressants or mood stabilizers) included (in overlapping categories) double-blind, comparative and noncomparative open-label studies, inpatient and outpatient studies, fixed- and flexible-dose studies, and short- and longer-term exposure.

The most common adverse reactions of aripiprazole in adult patients in clinical trials (≥10%) were nausea, vomiting, constipation, headache, dizziness, akathisia, anxiety, insomnia, and restlessness.

The most common adverse reactions of aripiprazole in the pediatric clinical trials (≥10%) were somnolence, headache, vomiting, extrapyramidal disorder, fatigue, increased appetite, insomnia, nausea, nasopharyngitis, and weight increased.

Adverse Reactions in Adult Patients with Schizophrenia

The following findings are based on a pool of five placebo-controlled trials (four 4 week and one 6 week) in which oral aripiprazole was administered in doses ranging from 2 mg/day to 30 mg/day.

The commonly observed adverse reaction associated with the use of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia (incidence of 5% or greater and aripiprazole incidence at least twice that for placebo) was akathisia (aripiprazole 8%; placebo 4%).

Table 13 enumerates the pooled incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of adverse reactions that occurred during acute therapy (up to 6 weeks in schizophrenia and up to 3 weeks in another indication), including only those reactions that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with aripiprazole (doses ≥2 mg/day) and for which the incidence in patients treated with aripiprazole was greater than the incidence in patients treated with placebo in the combined dataset.

Table 13: Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials in Adult Patients Treated with Oral Aripiprazole Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction* Preferred Term Aripiprazole

(n=1,843)Placebo

(n=1,166)- * Adverse reactions reported by at least 2% of patients treated with oral aripiprazole, except adverse reactions which had an incidence equal to or less than placebo.

Eye Disorders Blurred Vision 3 1 Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea 15 11 Constipation 11 7 Vomiting 11 6 Dyspepsia 9 7 Dry Mouth 5 4 Toothache 4 3 Abdominal Discomfort 3 2 Stomach Discomfort 3 2 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue 6 4 Pain 3 2 Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders Musculoskeletal Stiffness 4 3 Pain in Extremity 4 2 Myalgia 2 1 Muscle Spasms 2 1 Nervous System Disorders Headache 27 23 Dizziness 10 7 Akathisia 10 4 Sedation 7 4 Extrapyramidal Disorder 5 3 Tremor 5 3 Somnolence 5 3 Psychiatric Disorders Agitation 19 17 Insomnia 18 13 Anxiety 17 13 Restlessness 5 3 Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders Pharyngolaryngeal Pain 3 2 Cough 3 2 An examination of population subgroups did not reveal any clear evidence of differential adverse reaction incidence on the basis of age, gender, or race.

Adverse Reactions in Pediatric Patients (13 to 17 years) with Schizophrenia

The following findings are based on one 6-week, placebo-controlled trial in which oral aripiprazole was administered in doses ranging from 2 to 30 mg/day.

The incidence of discontinuation due to adverse reactions between aripiprazole-treated and placebo-treated pediatric patients (13 to 17 years) was 5% and 2%, respectively.

Commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of aripiprazole in pediatric patients 13 to 17 years with schizophrenia (incidence of 5% or greater and aripiprazole incidence at least twice that for placebo) were extrapyramidal disorder, somnolence, and tremor.

Adverse Reactions in Pediatric Patients (6 to 17 years) with Autistic Disorder

The following findings are based on two 8 week, placebo-controlled trials in which oral aripiprazole was administered in doses of 2 to 15 mg/day.

The incidence of discontinuation due to adverse reactions between aripiprazole-treated and placebo-treated pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) was 10% and 8%, respectively.

Commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of aripiprazole in pediatric patients (6 to 17 years) with autistic disorder (incidence of 5% or greater and aripiprazole incidence at least twice that for placebo) are shown in Table 14.

Table 14: Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Pediatric Patients (6 to 17 years) with Autistic Disorder Treated with Oral Aripiprazole Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction Preferred Term Aripiprazole

(n=212)Placebo

(n=101)Sedation 21 4 Fatigue 17 2 Vomiting 14 7 Somnolence 10 4 Tremor 10 0 Pyrexia 9 1 Drooling 9 0 Decreased Appetite 7 2 Salivary Hypersecretion 6 1 Extrapyramidal Disorder 6 0 Lethargy 5 0 Adverse Reactions in Pediatric Patients (6 to 18 years) with Tourette's Disorder

The following findings are based on one 8 week and one 10 week, placebo-controlled trials in which oral aripiprazole was administered in doses of 2 to 20 mg/day.

The incidence of discontinuation due to adverse reactions between aripiprazole-treated and placebo-treated pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) was 7% and 1%, respectively.

Commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of aripiprazole in pediatric patients (6 to 18 years) with Tourette's disorder (incidence of 5% or greater and aripiprazole incidence at least twice that for placebo) are shown in Table 15.

Table 15: Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Pediatric Patients (6 to 18 years) with Tourette's Disorder Treated with Oral Aripiprazole Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction Preferred Term Aripiprazole

(n=121)Placebo

(n=72)Sedation 13 6 Somnolence 13 1 Nausea 11 4 Headache 10 3 Nasopharyngitis 9 0 Fatigue 8 0 Increased Appetite 7 1 Table 16 enumerates the pooled incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of adverse reactions that occurred during acute therapy (up to 6 weeks in schizophrenia, up to 4 weeks in another indication, up to 8 weeks in autistic disorder, and up to 10 weeks in Tourette's disorder), including only those reactions that occurred in 2% or more of pediatric patients treated with aripiprazole (doses ≥2 mg/day) and for which the incidence in patients treated with aripiprazole was greater than the incidence in patients treated with placebo.

Table 16: Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Pediatric Patients (6 to 18 years) Treated with Oral Aripiprazole Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction* Preferred Term Aripiprazole

(n=732)Placebo

(n=370)- * Adverse reactions reported by at least 2% of pediatric patients treated with oral aripiprazole, except adverse reactions which had an incidence equal to or less than placebo.

Eye Disorders Blurred Vision 3 0 Gastrointestinal Disorders Abdominal Discomfort 2 1 Vomiting 8 7 Nausea 8 4 Diarrhea 4 3 Salivary Hypersecretion 4 1 Abdominal Pain Upper 3 2 Constipation 2 2 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue 10 2 Pyrexia 4 1 Irritability 2 1 Asthenia 2 1 Infections and Infestations Nasopharyngitis 6 3 Investigations Weight Increased 3 1 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Increased Appetite 7 3 Decreased Appetite 5 4 Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders Musculoskeletal Stiffness 2 1 Muscle Rigidity 2 1 Nervous System Disorders Somnolence 16 4 Headache 12 10 Sedation 9 2 Tremor 9 1 Extrapyramidal Disorder 6 1 Akathisia 6 4 Drooling 3 0 Lethargy 3 0 Dizziness 3 2 Dystonia 2 1 Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders Epistaxis 2 1 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Rash 2 1 Adverse Reactions in Adult Patients Receiving Aripiprazole as Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

The following findings are based on a pool of two placebo-controlled trials of patients with major depressive disorder in which aripiprazole was administered at doses of 2 to 20 mg as adjunctive treatment to continued antidepressant therapy.

The incidence of discontinuation due to adverse reactions was 6% for adjunctive aripiprazole-treated patients and 2% for adjunctive placebo-treated patients.

The commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of adjunctive aripiprazole in patients with major depressive disorder (incidence of 5% or greater and aripiprazole incidence at least twice that for placebo) were: akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and blurred vision.

Table 17 enumerates the pooled incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of adverse reactions that occurred during acute therapy (up to 6 weeks), including only those adverse reactions that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with adjunctive aripiprazole (doses ≥2 mg/day) and for which the incidence in patients treated with adjunctive aripiprazole was greater than the incidence in patients treated with adjunctive placebo in the combined dataset.

Table 17: Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Adjunctive Trials in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction* Preferred Term Aripiprazole + ADT†

(n=371)Placebo + ADT†

(n=366)- * Adverse reactions reported by at least 2% of patients treated with adjunctive Aripiprazole, except adverse reactions which had an incidence equal to or less than placebo.

- † Antidepressant Therapy

Eye Disorders Blurred Vision 6 1 Gastrointestinal Disorders Constipation 5 2 General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions Fatigue 8 4 Feeling Jittery 3 1 Infections and Infestations Upper Respiratory Tract Infection 6 4 Investigations Weight Increased 3 2 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Increased Appetite 3 2 Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders Arthralgia 4 3 Myalgia 3 1 Nervous System Disorders Akathisia 25 4 Somnolence 6 4 Tremor 5 4 Sedation 4 2 Dizziness 4 2 Disturbance in Attention 3 1 Extrapyramidal Disorder 2 0 Psychiatric Disorders Restlessness 12 2 Insomnia 8 2 Dose-Related Adverse Reactions

Schizophrenia

Dose response relationships for the incidence of adverse reactions were evaluated from four trials in adult patients with schizophrenia comparing various fixed doses (2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 mg/day) of oral aripiprazole to placebo. This analysis, stratified by study, indicated that the adverse reaction to have a possible dose response relationship, and then most prominent only with 30 mg, was somnolence [including sedation]; (incidences were placebo, 7.1%; 10 mg, 8.5%; 15 mg, 8.7%; 20 mg, 7.5%; 30 mg, 12.6%).

In the study of pediatric patients (13 to 17 years of age) with schizophrenia, three common adverse reactions appeared to have a possible dose response relationship: extrapyramidal disorder (incidences were placebo, 5.0%; 10 mg, 13.0%; 30 mg, 21.6%); somnolence (incidences were placebo, 6.0%; 10 mg, 11.0%; 30 mg, 21.6%); and tremor (incidences were placebo, 2.0%; 10 mg, 2.0%; 30 mg, 11.8%).

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Schizophrenia

In short-term, placebo-controlled trials in schizophrenia in adults, the incidence of reported EPS-related events, excluding events related to akathisia, for aripiprazole-treated patients was 13% vs. 12% for placebo; and the incidence of akathisiarelated events for aripiprazole-treated patients was 8% vs. 4% for placebo. In the short-term, placebo-controlled trial of schizophrenia in pediatric patients (13 to 17 years), the incidence of reported EPS-related events, excluding events related to akathisia, for aripiprazole-treated patients was 25% vs. 7% for placebo; and the incidence of akathisia-related events for aripiprazole-treated patients was 9% vs. 6% for placebo.

Objectively collected data from those trials was collected on the Simpson Angus Rating Scale (for EPS), the Barnes Akathisia Scale (for akathisia), and the Assessments of Involuntary Movement Scales (for dyskinesias). In the adult schizophrenia trials, the objectively collected data did not show a difference between aripiprazole and placebo, with the exception of the Barnes Akathisia Scale (aripiprazole, 0.08; placebo, –0.05). In the pediatric (13 to 17 years) schizophrenia trial, the objectively collected data did not show a difference between aripiprazole and placebo, with the exception of the Simpson Angus Rating Scale (aripiprazole, 0.24; placebo, –0.29).

Similarly, in a long-term (26 week), placebo-controlled trial of schizophrenia in adults, objectively collected data on the Simpson Angus Rating Scale (for EPS), the Barnes Akathisia Scale (for akathisia), and the Assessments of Involuntary Movement Scales (for dyskinesias) did not show a difference between aripiprazole and placebo.

Major Depressive Disorder

In the short-term, placebo-controlled trials in major depressive disorder, the incidence of reported EPS-related events, excluding events related to akathisia, for adjunctive aripiprazole- treated patients was 8% vs. 5% for adjunctive placebotreated patients; and the incidence of akathisia-related events for adjunctive aripiprazole-treated patients was 25% vs. 4% for adjunctive placebo-treated patients.

In the major depressive disorder trials, the Simpson Angus Rating Scale and the Barnes Akathisia Scale showed a significant difference between adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo (aripiprazole, 0.31; placebo, 0.03 and aripiprazole, 0.22; placebo, 0.02). Changes in the Assessments of Involuntary Movement Scales were similar for the adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo groups.

Autistic Disorder

In the short-term, placebo-controlled trials in autistic disorder in pediatric patients (6 to 17 years), the incidence of reported EPS-related events, excluding events related to akathisia, for aripiprazole-treated patients was 18% vs. 2% for placebo and the incidence of akathisia-related events for aripiprazole-treated patients was 3% vs. 9% for placebo.

In the pediatric (6 to 17 years) short-term autistic disorder trials, the Simpson Angus Rating Scale showed a significant difference between aripiprazole and placebo (aripiprazole, 0.1; placebo, – 0.4). Changes in the Barnes Akathisia Scale and the Assessments of Involuntary Movement Scales were similar for the aripiprazole and placebo groups.

Tourette's Disorder

In the short-term, placebo-controlled trials in Tourette's disorder in pediatric patients (6 to 18 years), the incidence of reported EPS-related events, excluding events related to akathisia, for aripiprazole-treated patients was 7% vs. 6% for placebo and the incidence of akathisia-related events for aripiprazole-treated patients was 4% vs. 6% for placebo.

In the pediatric (6 to 18 years) short-term Tourette's disorder trials, changes in the Simpson Angus Rating Scale, Barnes Akathisia Scale and Assessments of Involuntary Movement Scale were not clinically meaningfully different for aripiprazole and placebo.

Dystonia

Symptoms of dystonia, prolonged abnormal contractions of muscle groups, may occur in susceptible individuals during the first few days of treatment. Dystonic symptoms include spasm of the neck muscles, sometimes progressing to tightness of the throat, swallowing difficulty, difficulty breathing, and/or protrusion of the tongue. While these symptoms can occur at low doses, they occur more frequently and with greater severity with high potency and at higher doses of first generation antipsychotic drugs. An elevated risk of acute dystonia is observed in males and younger age groups.

Additional Findings Observed in Clinical Trials

Adverse Reactions in Long-Term, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials

The adverse reactions reported in a 26-week, double-blind trial comparing oral aripiprazole and placebo in patients with schizophrenia were generally consistent with those reported in the short-term, placebo-controlled trials, except for a higher incidence of tremor [8% (12/153) for aripiprazole tablets vs. 2% (3/153) for placebo]. In this study, the majority of the cases of tremor were of mild intensity (8/12 mild and 4/12 moderate), occurred early in therapy (9/12 ≤49 days), and were of limited duration (7/12 ≤10 days). Tremor led to discontinuation (<1%) of aripiprazole. In addition, in a long-term (52 weeks), active-controlled study, the incidence of tremor was 5% (40/859) for aripiprazole.

Other Adverse Reactions Observed During Clinical Trial Evaluation of Aripiprazole

Other adverse reactions associated with aripiprazole are presented below. The following listing does not include reactions: 1) already listed in previous tables or elsewhere in labeling, 2) for which a drug cause was remote, 3) which were so general as to be uninformative, 4) which were not considered to have significant clinical implications, or 5) which occurred at a rate equal to or less than placebo.

Reactions are categorized by body system according to the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1,000 patients; rare reactions are those occurring in fewer than 1/1,000 patients:

Adults - Oral Administration

- Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: rare - thrombocytopenia

- Cardiac Disorders: infrequent – bradycardia, palpitations, rare – atrial flutter, cardio-respiratory arrest, atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, angina pectoris, myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, cardiopulmonary failure

- Eye Disorders: infrequent – photophobia; rare - diplopia

- Gastrointestinal Disorders: infrequent - gastroesophageal reflux disease

- General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions: frequent - asthenia; infrequent – peripheral edema, chest pain; rare – face edema

- Hepatobiliary Disorders: rare - hepatitis, jaundice

- Immune System Disorders: rare - hypersensitivity

- Injury, Poisoning, and Procedural Complications: infrequent - fall; rare-heat stroke

- Investigations: frequent - blood prolactin decreased, weight decreased, infrequent - hepatic enzyme increased, blood glucose increased, blood lactate dehydrogenase increased, gamma glutamyl transferase increased; rare - blood prolactin increased, blood urea increased, blood creatinine increased, blood bilirubin increased, electrocardiogram QT prolonged, glycosylated hemoglobin increased

- Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders: frequent – anorexia; rare - hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia

- Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: infrequent - muscular weakness, muscle tightness; rare – rhabdomyolysis, mobility decreased

- Nervous System Disorders: infrequent - parkinsonism, memory impairment, cogwheel rigidity, hypokinesia, bradykinesia; rare – akinesia, myoclonus, coordination abnormal, speech disorder, Grand Mal convulsion; <1/10,000 patients - choreoathetosis

- Psychiatric Disorders: infrequent – aggression, loss of libido, delirium; rare - libido increased, anorgasmia, tic, homicidal ideation, catatonia, sleep walking

- Renal and Urinary Disorders: rare - urinary retention, nocturia

- Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: infrequent - erectile dysfunction; rare - gynaecomastia, menstruation irregular, amenorrhea, breast pain, priapism

- Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders: infrequent - nasal congestion, dyspnea

- Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: infrequent - rash, hyperhidrosis, pruritus, photosensitivity reaction, alopecia; rare - urticaria

- Vascular Disorders: infrequent – hypotension, hypertension

Pediatric Patients - Oral Administration

Most adverse reactions observed in the pooled database of 1,686 pediatric patients, aged 6 to 18 years, were also observed in the adult population. Additional adverse reactions observed in the pediatric population are listed below.

- Eye Disorders: infrequent - oculogyric crisis

- Gastrointestinal Disorders: infrequent -tongue dry, tongue spasm

- Investigations: frequent - blood insulin increased

- Nervous System Disorders: infrequent - sleep talking

- Renal and Urinary Disorders: frequent - enuresis

- Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: infrequent- hirsutism

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of aripiprazole. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure: occurrences of allergic reaction (anaphylactic reaction, angioedema, laryngospasm, pruritus/urticaria, or oropharyngeal spasm), blood glucose fluctuation, Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), hiccups, oculogyric crisis, and pathological gambling.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Drugs Having Clinically Important Interactions with OPIPZA

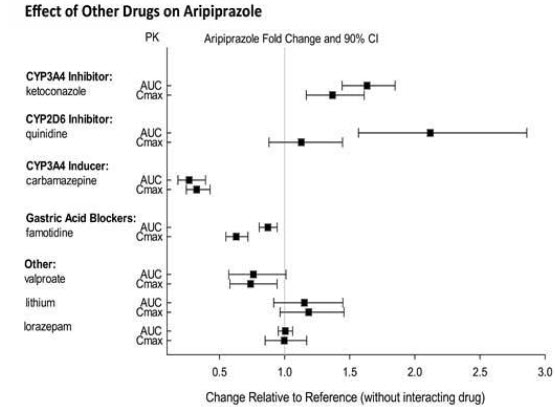

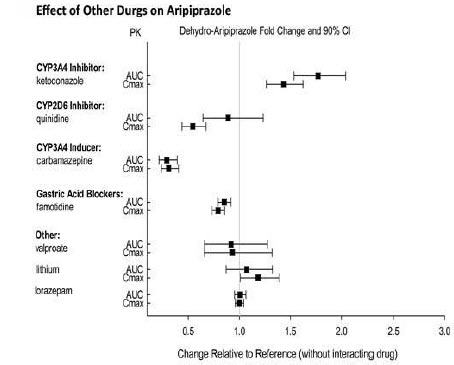

Table 18 includes clinically important drug interactions with OPIPZA.

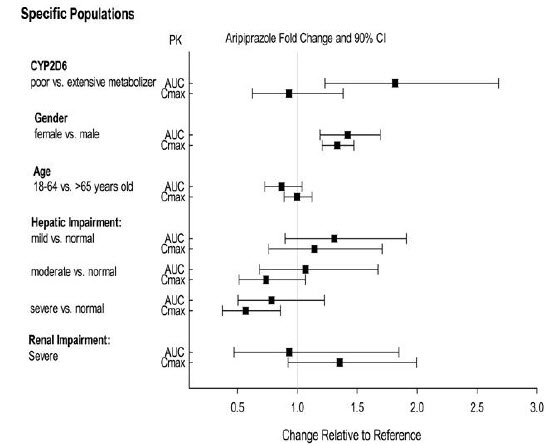

Table 18: Clinically Important Drug Interactions with OPIPZA Strong CYP3A4 Inhibitors AND/OR Strong CYP2D6 Inhibitors Clinical Rationale Concomitant use of aripiprazole with strong CYP3A4 and/or CYP2D6 inhibitors increased the exposure of aripiprazole [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Clinical Recommendation Reduce the dosage of OPIPZA when administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor and/or strong CYP2D6 inhibitor [see Dosage and Administration (2.6)]. Strong CYP3A4 Inducers Clinical Rationale Concomitant use of aripiprazole and carbamazepine decreased the exposure of aripiprazole [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Clinical Recommendation Consider increasing the dosage of OPIPZA when administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inducer [see Dosage and Administration (2.6)]. Antihypertensive Drugs Clinical Rationale Due to its alpha-adrenergic antagonism, aripiprazole has the potential to enhance the effect of certain antihypertensive agents. Clinical Recommendation Monitor blood pressure and adjust dose accordingly [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]. Benzodiazepines Clinical Rationale The intensity of sedation was greater with the combination of oral aripiprazole and lorazepam as compared to that observed with aripiprazole alone. The orthostatic hypotension observed was greater with the combination as compared to that observed with lorazepam alone [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]. Clinical Recommendation Monitor sedation and blood pressure. Adjust dose accordingly. 7.2 Drugs Having No Clinically Important Interactions with OPIPZA

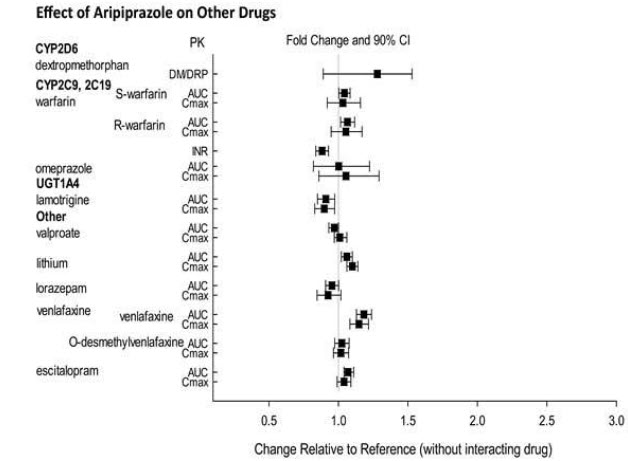

Based on pharmacokinetic studies, no dosage adjustment of aripiprazole is required when administered concomitantly with famotidine, valproate, lithium, lorazepam.

In addition, no dosage adjustment is necessary for substrates of CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, or CYP3A4 when coadministered with OPIPZA. Additionally, no dosage adjustment is necessary for valproate, lithium, lamotrigine, lorazepam, or sertraline when co-administered with OPIPZA [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to atypical antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, during pregnancy. Healthcare providers are encouraged to advise patients to register by contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visiting online at http://womensmentalhealth.org/clinical-and-research-programs/pregnancyregistry/.

Risk Summary

Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs, including OPIPZA, during the third trimester of pregnancy are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery (see Clinical Considerations). Overall available data from published epidemiologic studies of pregnant women exposed to aripiprazole have not established a drug-associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes (see Data). There are risks to the mother associated with untreated schizophrenia, or major depressive disorder, and with exposure to antipsychotics, including OPIPZA during pregnancy (see Clinical Considerations).

In animal reproduction studies, oral and intravenous aripiprazole administration during organogenesis in rats and/or rabbits at doses 10 and 19 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 30 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area, produced fetal death, decreased fetal weight, undescended testicles, delayed skeletal ossification, skeletal abnormalities, and diaphragmatic hernia. Oral and intravenous aripiprazole administration during the pre- and post-natal period in rats at doses 10 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area, produced prolonged gestation, stillbirths, decreased pup weight, and decreased pup survival (see Data).

The background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 % to 4% and 15% to 20%, respectively.

Clinical Considerations

Disease-associated maternal and/or embryo/fetal risk

There is a risk to the mother from untreated schizophrenia, including increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and suicide. Schizophrenia is associated with increased adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth. It is not known if this is a direct result of the illness or other comorbid factors.

A prospective, longitudinal study followed 201 pregnant women with a history of major depressive disorder who were euthymic and taking antidepressants at the beginning of pregnancy. The women who discontinued antidepressants during pregnancy were more likely to experience a relapse of major depression than women who continued antidepressants. Consider the risk of untreated depression when discontinuing or changing treatment with antidepressant medication during pregnancy and postpartum.

Fetal/Neonatal Adverse Reactions

Extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms, including agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, and feeding disorder have been reported in neonates who were exposed to antipsychotic drugs (including aripiprazole) during the third trimester of pregnancy. These symptoms have varied in severity. Monitor neonates for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms and manage symptoms appropriately. Some neonates recovered within hours or days without specific treatment; others required prolonged hospitalization.

Data

Human Data

Published data from observational studies, birth registries, and case reports on the use of atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy do not report a clear association with antipsychotics and major birth defects. A retrospective study from a Medicaid database of 9,258 women exposed to antipsychotics during pregnancy did not indicate an overall increased risk for major birth defects.

Animal Data

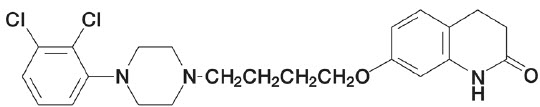

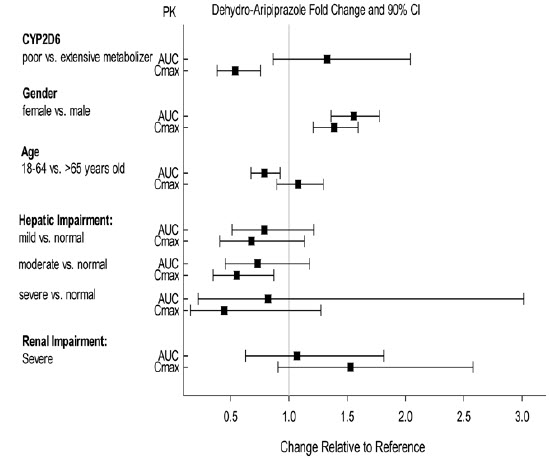

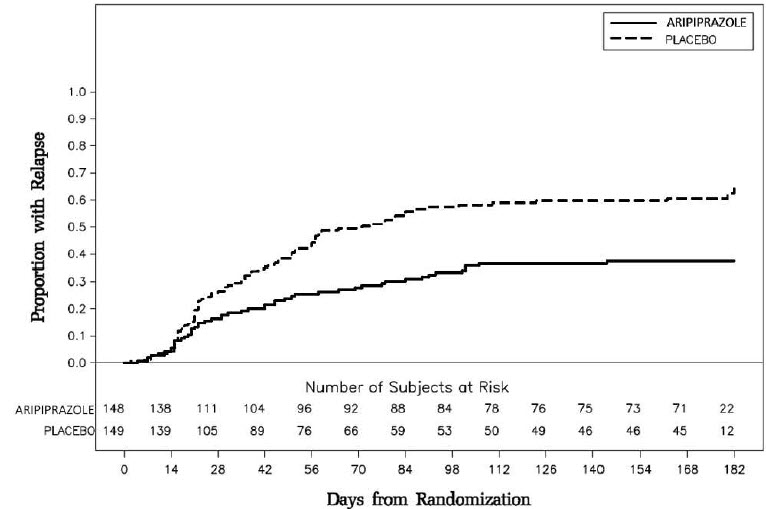

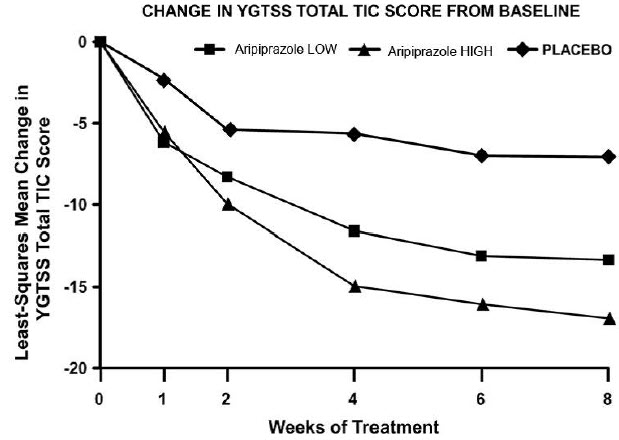

In animal studies, aripiprazole demonstrated developmental toxicity, including possible teratogenic effects in rats and rabbits.