Risperidone by Dr. Reddy's Laboratories Limited / Bio-Pharm, Inc. RISPERIDONE solution

Risperidone by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Risperidone by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Dr. Reddy's Laboratories Limited, Bio-Pharm, Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use risperidone safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for risperidone.

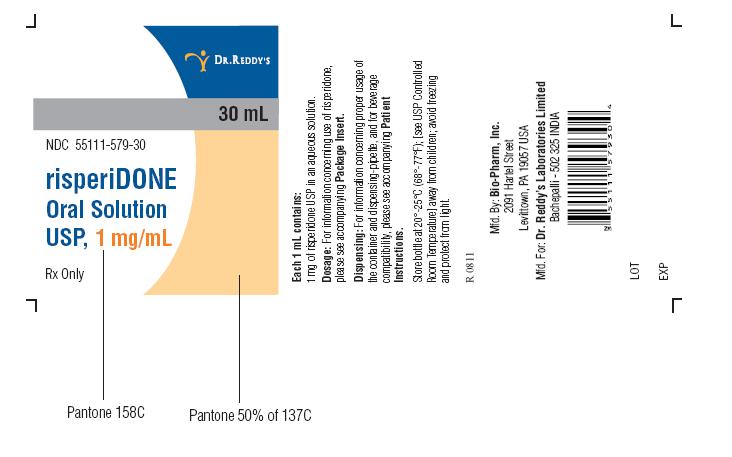

Risperidone Oral Solution USP

Initial U.S. Approval: 1993WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSISSee full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Risperidone is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis. (5.1)

RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

Warnings and Precautions, Metabolic Changes (5.5) September 2011

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Risperidone is an atypical antipsychotic agent indicated for: (1)

-

Treatment of schizophrenia in adults and adolescents aged 13-17 years(1.1) (1)

- Alone, or in combination with lithium or valproate, for the short-term treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder in adults and alone in children and adolescents aged 10-17 years (1.2)

-

Treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in children and adolescents aged 5-16 years (1.3)

(1)

(1)

(1)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

(2)

Initial Dose Titration Target Dose Effective Dose Range Schizophrenia – adults (2.1) 2 mg /day 1-2 mg daily 4-8 mg daily 4-16 mg /day Schizophrenia - adolescents (2.1) 0.5 mg/day 0.5-1 mg daily 3 mg/day 1-6 mg/day Bipolar mania – adults (2.2) 2-3 mg /day 1 mg daily 1-6 mg /day 1-6 mg /day Bipolar mania in children/adolescents (2.2) 0.5 mg/day 0.5-1 mg daily 2.5 mg/day 0.5-6 mg/day Irritability associated with autistic disorder (2.3) 0.25 mg/day(<20 kg)0.5 mg/day(≥20 kg) 0.25-0.5 mgat ≥ 2 weeks 0.5 mg/day(<20 kg)1 mg/day(≥20 kg) 0.5-3 mg/day DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- Oral Solution: 1 mg/mL (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Known hypersensitivity to the product (4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Cerebrovascular events, including stroke, in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.

Risperidone is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis (5.2) (5)

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (5.3)

- Tardive dyskinesia (5.4)

- Metabolic Changes: Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/ cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and weight gain. (5.5)

o Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus: Monitor patients for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Monitor glucose regularly in patients with diabetes or at risk for diabetes. (5.5)

o Dyslipidemia: Undesirable alterations have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. (5.5)

o Weight Gain: Significant weight gain has been reported. Monitor weight gain. (5.5) - Hyperprolactinemia (5.6)

- Orthostatic hypotension (5.7)

- Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis: has been reported with antipsychotics, including risperidone. Patients with a history of a clinically significant low white blood cell count (WBC) or a drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and discontinuation of risperidone should be considered at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors. (5.8)

- Potential for cognitive and motor impairment (5.9)

-

Seizures (5.10) (5)

-

Dysphagia (5.11) (5)

- Priapism (5.12)

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) (5.13)

- Disruption of body temperature regulation (5.14)

- Antiemetic Effect (5.15)

- Suicide (5.16)

- Increased sensitivity in patients with Parkinson’s disease or those with dementia with Lewy bodies (5.17)

- Diseases or conditions that could affect metabolism or hemodynamic responses (5.17)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common adverse reactions in clinical trials (≥10%) were somnolence, increased appetite, fatigue, insomnia, sedation, parkinsonism, akathisia, vomiting, cough, constipation, nasopharyngitis, drooling, rhinorrhea, dry mouth, abdominal pain upper, dizziness, nausea, anxiety, headache, nasal congestion, rhinitis, tremor, and rash. (6)

The most common adverse reactions that were associated with discontinuation from clinical trials were nausea, somnolence, sedation, vomiting, dizziness, and akathisia. (6)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc. at 1-888-375-3784 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch

DRUG INTERACTIONS

-

Due to CNS effects, use caution when administering with other centrally acting drugs. Avoid alcohol. (7.1) (7)

-

Due to hypotensive effects, hypotensive effects of other drugs with this potential may be enhanced. (7.2) (7)

-

Effects of levodopa and dopamine agonists may be antagonized. (7.3) (7)

-

Cimetidine and ranitidine increase the bioavailability of risperidone. (7.5) (7)

-

Clozapine may decrease clearance of risperidone. (7.6) (7)

-

Fluoxetine and paroxetine increase plasma concentrations of risperidone. (7.10) (7)

-

Carbamazepine and other enzyme inducers decrease plasma concentrations of risperidone. (7.11) (7)

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

-

Nursing Mothers: should not breast feed. (8.3) (8)

-

Pediatric Use: safety and effectiveness not established for schizophrenia less than 13 years of age, for bipolar mania less than 10 years of age and for autistic disorder less than 5 years of age. (8.4) (8)

-

Elderly or debilitated; severe renal or hepatic impairment; predisposition to hypotension or for whom hypotension poses a risk: Lower initial dose (0.5 mg twice daily), followed by increases in dose in increments of no more than 0.5 mg twice daily. Increases to dosages above 1.5 mg twice daily should occur at intervals of at least 1 week. (8.5, 2.4) (8)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION.

Revised: 7/2009

-

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

WARNINGS : INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Schizophrenia

1.2 Bipolar Mania

1.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Schizophrenia

2.2 Bipolar Mania

2.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder – Pediatrics (Children and Adolescents)

2.4 Dosage in Special Populations

2.5 Co-Administration of Risperidone with Certain Other Medications

2.6 Administration of Risperidone Oral Solution

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

5.2 Cerebrovascular Adverse Events, Including Stroke, in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

5.3 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

5.4 Tardive Dyskinesia

5.5 Metabolic changes

5.6 Hyperprolactinemia

5.7 Orthostatic Hypotension

5.8 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

5.9 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

5.10 Seizures

5.11 Dysphagia

5.12 Priapism

5.13 Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

5.14 Body Temperature Regulation

5.15 Antiemetic Effect

5.16 Suicide

5.17 Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness

5.18 Monitoring: Laboratory Tests

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials – Schizophrenia

6.2 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials – Bipolar Mania

6.3 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials - Autistic Disorder

6.4 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Risperidone

6.5 Discontinuations Due to Adverse Reactions

6.6 Dose Dependency of Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials

6.7 Changes in ECG

6.8 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Centrally-Acting Drugs and Alcohol

7.2 Drugs with Hypotensive Effects

7.3 Levodopa and Dopamine Agonists

7.4 Amitriptyline

7.5 Cimetidine and Ranitidine

7.6 Clozapine

7.7 Lithium

7.8 Valproate

7.9 Digoxin

7.10 Drugs That Inhibit CYP 2D6 and Other CYP Isozymes

7.11 Carbamazepine and Other Enzyme Inducers

7.12 Drugs Metabolized by CYP 2D6

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Labor and Delivery

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

10.2 Management of Overdosage

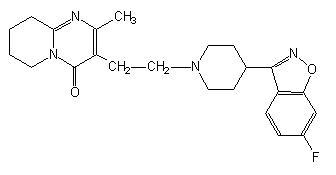

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment Of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Schizophrenia

14.2 Bipolar Mania - Monotherapy

14.3 Bipolar Mania - Combination Therapy

14.4 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

Storage and Handling

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

17.1 Orthostatic Hypotension

17.2 Interference with Cognitive and Motor Performance

17.3 Pregnancy

17.4 Nursing

17.5 Concomitant Medication

17.6 Alcohol

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNINGS : INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of 17 placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. Risperidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. (See Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Schizophrenia

Adults

Risperidone oral solution is indicated for the acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia [see Clinical Studies(14.1)].

Adolescents

Risperidone oral solution is indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents aged 13 to 17 years [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

1.2 Bipolar Mania

Monotherapy - Adults and Pediatrics

Risperidone oral solution is indicated for the short-term treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder in adults and in children and adolescents aged 10 to 17 years[see Clinical Studies(14.2)].

Combination Therapy – Adults

The combination of risperidone with lithium or valproate is indicated for the short-term treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder [see Clinical Studies(14.3)].

1.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder

Pediatrics

Risperidone oral solution is indicated for the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in children and adolescents aged 5 to16 years, including symptoms of aggression towards others, deliberate self-injuriousness, temper tantrums, and quickly changing moods [see Clinical Studies (14.4) ].

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Schizophrenia

Adults

Usual Initial Dose

Risperidone oral solution can be administered once or twice daily. Initial dosing is generally 2 mg/day. Dose increases should then occur at intervals not less than 24 hours, in increments of 1-2 mg/day, as tolerated, to a recommended dose of 4-8 mg/day. In some patients, slower titration may be appropriate. Efficacy has been demonstrated in a range of 4-16 mg/day [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]. However, doses above 6 mg/day for twice daily dosing were not demonstrated to be more efficacious than lower doses, were associated with more extrapyramidal symptoms and other adverse effects, and are generally not recommended. In a single study supporting once-daily dosing, the efficacy results were generally stronger for 8 mg than for 4 mg. The safety of doses above 16 mg/day has not been evaluated in clinical trials.

Maintenance Therapy

While it is unknown how long a patient with schizophrenia should remain on risperidone, the effectiveness of risperidone 2 mg/day to 8 mg/day at delaying relapse was demonstrated in a controlled trial in patients who had been clinically stable for at least 4 weeks and were then followed for a period of 1 to 2 years [see Clinical Studies(14.1)]. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment with an appropriate dose.

Adolescents

The dosage of risperidone should be initiated at 0.5 mg once daily, administered as a single-daily dose in either the morning or evening. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, should occur at intervals not less than 24 hours, in increments of 0.5 or 1 mg/day, as tolerated, to a recommended dose of 3 mg/day. Although efficacy has been demonstrated in studies of adolescent patients with schizophrenia at doses between 1 and 6 mg/day, no additional benefit was seen above 3 mg/day, and higher doses were associated with more adverse events. Doses higher than 6 mg/day have not been studied.

Patients experiencing persistent somnolence may benefit from administering half the daily dose twice daily.

There are no controlled data to support the longer term use of risperidone beyond 8 weeks in adolescents with schizophrenia. The physician who elects to use risperidone for extended periods in adolescents with schizophrenia should periodically re-evaluate the long-term risks and benefits of the drug for the individual patient.

Reinitiation of Treatment in Patients Previously Discontinued

Although there are no data to specifically address reinitiation of treatment, it is recommended that after an interval off risperidone, the initial titration schedule should be followed.

Switching From Other Antipsychotics

There are no systematically collected data to specifically address switching schizophrenic patients from other antipsychotics to risperidone, or treating patients with concomitant antipsychotics. While immediate discontinuation of the previous antipsychotic treatment may be acceptable for some schizophrenic patients, more gradual discontinuation may be most appropriate for others. The period of overlapping antipsychotic administration should be minimized. When switching schizophrenic patients from depot antipsychotics, initiate risperidone therapy in place of the next scheduled injection. The need for continuing existing EPS medication should be re-evaluated periodically.

2.2 Bipolar Mania

Usual Dose

Adults

Risperidone should be administered on a once-daily schedule, starting with 2 mg to 3 mg per day. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, should occur at intervals of not less than 24 hours and in dosage increments/decrements of 1 mg per day, as studied in the short-term, placebo-controlled trials. In these trials, short-term (3 week) anti-manic efficacy was demonstrated in a flexible dosage range of 1-6 mg per day [see Clinical Studies(14.2, 14.3)]. Risperidone doses higher than 6 mg per day were not studied.

Pediatrics

The dosage of risperidone should be initiated at 0.5 mg once daily, administered as a single-daily dose in either the morning or evening. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, should occur at intervals not less than 24 hours, in increments of 0.5 or 1 mg/day, as tolerated, to a recommended dose of 2.5 mg/day. Although efficacy has been demonstrated in studies of pediatric patients with bipolar mania at doses between 0.5 and 6 mg/day, no additional benefit was seen above 2.5 mg/day, and higher doses were associated with more adverse events. Doses higher than 6 mg/day have not been studied.

Patients experiencing persistent somnolence may benefit from administering half the daily dose twice daily.

Maintenance Therapy

There is no body of evidence available from controlled trials to guide a clinician in the longer-term management of a patient who improves during treatment of an acute manic episode with risperidone. While it is generally agreed that pharmacological treatment beyond an acute response in mania is desirable, both for maintenance of the initial response and for prevention of new manic episodes, there are no systematically obtained data to support the use of risperidone in such longer-term treatment (i.e., beyond 3 weeks). The physician who elects to use risperidone for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term risks and benefits of the drug for the individual patient.

2.3 Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder – Pediatrics (Children and Adolescents)

The safety and effectiveness of risperidone in pediatric patients with autistic disorder less than 5 years of age have not been established.

The dosage of risperidone should be individualized according to the response and tolerability of the patient. The total daily dose of risperidone can be administered once daily, or half the total daily dose can be administered twice daily.

Dosing should be initiated at 0.25 mg per day for patients < 20 kg and 0.5 mg per day for patients ≥ 20 kg. After a minimum of four days from treatment initiation, the dose may be increased to the recommended dose of 0.5 mg per day for patients < 20 kg and 1 mg per day for patients ≥ 20 kg. This dose should be maintained for a minimum of 14 days. In patients not achieving sufficient clinical response, dose increases may be considered at ≥ 2-week intervals in increments of 0.25 mg per day for patients < 20 kg or 0.5 mg per day for patients ≥ 20 kg. Caution should be exercised with dosage for smaller children who weigh less than 15 kg.

In clinical trials, 90% of patients who showed a response (based on at least 25% improvement on ABC-I, [see Clinical Studies (14.4)] received doses of risperidonebetween 0.5 mg and 2.5 mg per day. The maximum daily dose of risperidonein one of the pivotal trials, when the therapeutic effect reached plateau, was 1 mg in patients < 20 kg, 2.5 mg in patients ≥ 20 kg, or 3 mg in patients > 45 kg. No dosing data is available for children who weighed less than 15 kg.

Once sufficient clinical response has been achieved and maintained, consideration should be given to gradually lowering the dose to achieve the optimal balance of efficacy and safety. The physician who elects to use risperidonefor extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term risks and benefits of the drug for the individual patient.

Patients experiencing persistent somnolence may benefit from a once-daily dose administered at bedtime or administering half the daily dose twice daily, or a reduction of the dose.

2.4 Dosage in Special Populations

The recommended initial dose is 0.5 mg twice daily in patients who are elderly or debilitated, patients with severe renal or hepatic impairment, and patients either predisposed to hypotension or for whom hypotension would pose a risk. Dosage increases in these patients should be in increments of no more than 0.5 mg twice daily. Increases to dosages above 1.5 mg twice daily should generally occur at intervals of at least 1 week. In some patients, slower titration may be medically appropriate.

Elderly or debilitated patients, and patients with renal impairment, may have less ability to eliminate risperidone than normal adults. Patients with impaired hepatic function may have increases in the free fraction of risperidone, possibly resulting in an enhanced effect [see ClinicalPharmacology(12.3)]. Patients with a predisposition to hypotensive reactions or for whom such reactions would pose a particular risk likewise need to be titrated cautiously and carefully monitored [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2,5.7,5.17)]. If a once-daily dosing regimen in the elderly or debilitated patient is being considered, it is recommended that the patient be titrated on a twice-daily regimen for 2-3 days at the target dose. Subsequent switches to a once-daily dosing regimen can be done thereafter.

2.5 Co-Administration of Risperidone with Certain Other Medications

Co-administration of carbamazepine and other enzyme inducers (e.g., phenytoin, rifampin, phenobarbital) with risperidone would be expected to cause decreases in the plasma concentrations of the sum of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone combined, which could lead to decreased efficacy of risperidone treatment. The dose of risperidone needs to be titrated accordingly for patients receiving these enzyme inducers, especially during initiation or discontinuation of therapy with these inducers [see Drug Interactions (7.11)].

Fluoxetine and paroxetine have been shown to increase the plasma concentration of risperidone 2.5-2.8 fold and 3-9 fold, respectively. Fluoxetine did not affect the plasma concentration of 9-hydroxyrisperidone. Paroxetine lowered the concentration of 9-hydroxyrisperidone by about 10%. The dose of risperidone needs to be titrated accordingly when fluoxetine or paroxetine is co-administered [see Drug Interactions (7.10)].

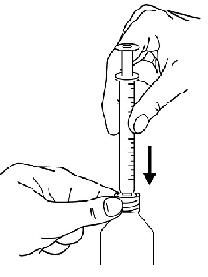

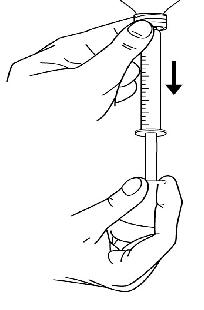

2.6 Administration of Risperidone Oral Solution

Risperidone Oral Solution can be administered directly from the calibrated pipette, or can be mixed with a beverage prior to administration. Risperidone Oral Solution is compatible in the following beverages: water, coffee, orange juice, and low-fat milk; it is NOT compatible with either cola or tea.

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- 4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Risperidone is not approved for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warning].

5.2 Cerebrovascular Adverse Events, Including Stroke, in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Cerebrovascular adverse events (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack), including fatalities, were reported in patients (mean age 85 years; range 73-97) in trials of risperidone in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. In placebo-controlled trials, there was a significantly higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events in patients treated with risperidone compared to patients treated with placebo. Risperidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. [See also Boxed Warnings and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

5.3 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with antipsychotic drugs. Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with this syndrome is complicated. In arriving at a diagnosis, it is important to identify cases in which the clinical presentation includes both serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection, etc.) and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal signs and symptoms (EPS). Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever, and primary central nervous system pathology.

The management of NMS should include: (1) immediate discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs and other drugs not essential to concurrent therapy; (2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and (3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for uncomplicated NMS.

If a patient requires antipsychotic drug treatment after recovery from NMS, the potential reintroduction of drug therapy should be carefully considered. The patient should be carefully monitored, since recurrences of NMS have been reported.

5.4 Tardive Dyskinesia

A syndrome of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements may develop in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to rely upon prevalence estimates to predict, at the inception of antipsychotic treatment, which patients are likely to develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible are believed to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose of antipsychotic drugs administered to the patient increase. However, the syndrome can develop, although much less commonly, after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses.

There is no known treatment for established cases of tardive dyskinesia, although the syndrome may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn. Antipsychotic treatment, itself, however, may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome and thereby may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, risperidone should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who suffer from a chronic illness that: (1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs, and (2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient treated with risperidone, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment with risperidone despite the presence of the syndrome.

5.5 Metabolic changes

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and body weight gain. While all of the drugs in the class have been shown to produce some metabolic changes, each drug has its own specific risk profile.

Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, have been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics including risperidone. Assessment of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and glucose abnormalities is complicated by the possibility of an increased background risk of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia and the increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus in the general population. Given these confounders, the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and hyperglycemia-related adverse events is not completely understood. However, epidemiological studies suggest an increased risk of treatment-emergent hyperglycemia-related adverse events in patients treated with the atypical antipsychotics. Precise risk estimates for hyperglycemia-related adverse events in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics are not available.

Patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment with atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, should undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic, including risperidone, was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of anti-diabetic treatment despite discontinuation of risperidone

Pooled data from three double-blind, placebo-controlled schizophrenia studies and four double-blind, placebo-controlled bipolar monotherapy studies are presented in Table 1a.

Table 1a. Change in Random Glucose from Seven Placebo-Controlled, 3- to 8-Week, Fixed- or Flexible-Dose Studies in Adult Subjects with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Mania

Risperidone Placebo 1 to 8 mg/day >8 to16 mg/day Mean change from baseline (mg/dL) n=555 n=748 n=164 Serum Glucose -1.4 0.8 0.6 Proportion of patients with shifts Serum Glucose

(<140 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL)0.6%

(3/525)0.4%

(3/702)0%

(0/158)In longer-term, controlled and uncontrolled studies, risperidonewas associated with a mean change in glucose of +2.8 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=151) and +4.1 mg/dL at Week 48 (n=50).

Data from the placebo-controlled 3- to 6-week study in children and adolescents with schizophrenia (13 to 17 years of age), bipolar mania (10 to 17 years of age), or autistic disorder (5 to 17 years of age) are presented in Table 1b.

Table 1b. Change in Fasting Glucose from Three Placebo-Controlled, 3- to 6-Week, Fixed-Dose Studies in Children and Adolescents with Schizophrenia (13 to 17 years of age), Bipolar Mania (10 to 17 years of age), or Autistic Disorder (5 to 17 years of age)

Placebo Risperidone0.5 to 6 mg/day Mean change from baseline (mg/dL) N=76 N=135 Serum Glucose -1.3 2.6 Proportion of patients with shifts Serum Glucose

(<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL)0%

(0/64)0.8%

(1/120)In longer-term, uncontrolled, open-label extension pediatric studies, risperidone was associated with a mean change in fasting glucose of +5.2 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=119).

Dyslipidemia

Undesirable alterations in lipids have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Pooled data from 7 placebo-controlled, 3- to 8- week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies in adult subjects with schizophrenia or bipolar mania are presented in Table 2a.

Table 2a. Change in Random Lipids From Seven Placebo-Controlled, 3-to 8-Week, Fixed- or Flexible-Dose Studies in Adult Subjects With Schizophrenia or Bipolar Mania

Risperidone Placebo 1 to 8 mg/day >8 to16 mg/day Mean change from baseline (mg/dL) Cholesterol n=559 n=742 n=156 Change from baseline 0.6 6.9 1.8 Triglycerides n=183 n=307 n=123 Change from baseline -17.4 -4.9 -8.3 Proportion of patients with shifts Cholesterol 2.7% 4.3% 6.3% (<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) (10/368) (22/516) (6/96) Triglycerides 1.1% 2.7% 2.5% (<500 mg/dL to ≥500 mg/dL) (2/180) (8/301) (3/121) In longer-term, controlled and uncontrolled studies, risperidonewas associated with a mean change in (a) non-fasting cholesterol of +4.4 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=231) and +5.5 mg/dL at Week 48 (n=86); and (b) non-fasting triglycerides of +19.9 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=52).

Pooled data from 3 placebo-controlled, 3- to 6-week, fixed-dose studies in children and adolescents with schizophrenia (13 to17 years of age), bipolar mania (10 to 17 years of age), or autistic disorder (5 to17 years of age) are presented in Table 2b.

Table 2b. Change in Fasting Lipids From Three Placebo-Controlled, 3- to 6-Week, Fixed-Dose Studies in Children and Adolescents With Schizophrenia (13 to 17 Years of Age), Bipolar Mania (10 to 17 Years of Age), or Autistic Disorder (5 to 17 Years of Age)

Risperidone Placebo 0.5 to 6 mg/day Mean change from baseline (mg/dL) Cholesterol n=74 n=133 Change from baseline 0.3 -0.3 LDL n=22 n=22 Change from baseline 3.7 0.5 HDL n=22 n=22 Change from baseline 1.6 -1.9 Triglycerides n=77 n=138 Change from baseline -9.0 -2.6 Proportion of patients with shifts Cholesterol 2.4% 3.8% (<170 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) (1/42) (3/80) LDL 0% 0% (<110 mg/dL to ≥130 mg/dL) (0/16) (0/16) HDL 0% 10% (≥40 mg/dL to <40 mg/dL) (0/19) (2/20) Triglycerides 1.5% 7.1% (<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) (1/65) (8/113) In longer-term, uncontrolled, open-label extension pediatric studies, risperidonewas associated with a mean change in (a) fasting cholesterol of +2.1 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=114); (b) fasting LDL of -0.2 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=103); (c) fasting HDL of +0.4 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=103); and (d) fasting triglycerides of +6.8 mg/dL at Week 24 (n=120).

Weight Gain

Weight gain has been observed with atypical antipsychotic use. Clinical monitoring of weight is recommended.

Data on mean changes in body weight and the proportion of subjects meeting a weight gain criterion of 7% or greater of body weight from 7 placebo-controlled, 3- to 8- week, fixed- or flexible-dose studies in adult subjects with schizophrenia or bipolar mania are presented in Table 3a.

Table 3a. Mean Change in Body Weight (kg) and the Proportion of Subjects with ≥7% Gain in Body Weight From Seven Placebo-Controlled, 3- to 8-Week, Fixed-or Flexible-Dose Studies in Adult Subjects With Schizophrenia or Bipolar Mania

Risperidone Placebo

(n=597)1 to 8 mg/day

(n=769)>8 to16 mg/day

(n=158)Weight (kg)

Change from baseline

-0.3

0.7

2.2Weight Gain

≥7% increase from baseline

2.9%

8.7%

20.9%In longer-term, controlled and uncontrolled studies, risperidonewas associated with a mean change in weight of +4.3 kg at Week 24 (n=395) and +5.3 kg at Week 48 (n=203).

Data on mean changes in body weight and the proportion of subjects meeting the criterion of ≥7% gain in body weight from nine placebo-controlled, 3- to 8-week, fixed-dose studies in children and adolescents with schizophrenia (13 to 17 years of age), bipolar mania (10 to 17 years of age), autistic disorder (5 to 17 years of age), or other psychiatric disorders (5 to 17 years of age) are presented in Table 3b.

Table 3b. Mean Change in Body Weight (kg) and the Proportion of Subjects With ≥7% Gain in Body Weight From Nine Placebo-Controlled, 3- to 8-Week, Fixed-Dose Studies in Children and Adolescents With Schizophrenia (13 to 17 Years of Age), Bipolar Mania (10 to 17 Years of Age), Autistic Disorder (5 to 17 Years of Age) or Other Psychiatric Disorders (5 to 17 Years of Age)

Placebo

(n=375)Risperidone

0.5 to 6 mg/day

(n=448)Weight (kg)

Change from baseline

0.6

2.0Weight Gain

≥7% increase from baseline

6.9%

32.6%In longer-term, uncontrolled, open-label extension pediatric studies, risperidonewas associated with a mean change in weight of +5.5 kg at Week 24 (n=748) and +8.0 kg at Week 48 (n=242). .

5.6 Hyperprolactinemia

As with other drugs that antagonize dopamine D2 receptors, risperidone elevates prolactin levels and the elevation persists during chronic administration. Risperidone is associated with higher levels of prolactin elevation than other antipsychotic agents.

Hyperprolactinemia may suppress hypothalamic GnRH, resulting in reduced pituitary gonadotropin secretion. This, in turn, may inhibit reproductive function by impairing gonadal steroidogenesis in both female and male patients. Galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence have been reported in patients receiving prolactin-elevating compounds. Long standing hyperprolactinemia when associated with hypogonadism may lead to decreased bone density in both female and male subjects.

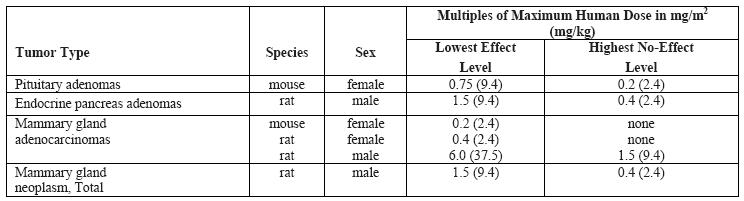

Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if the prescription of these drugs is contemplated in a patient with previously detected breast cancer. An increase in pituitary gland, mammary gland, and pancreatic islet cell neoplasia (mammary adenocarcinomas, pituitary and pancreatic adenomas) was observed in the risperidone carcinogenicity studies conducted in mice and rats [see Non-Clinical Toxicology(13.1)]. Neither clinical studies nor epidemiologic studies conducted to date have shown an association between chronic administration of this class of drugs and tumorigenesis in humans; the available evidence is considered too limited to be conclusive at this time.

5.7 Orthostatic Hypotension

Risperidone may induce orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, tachycardia, and in some patients, syncope, especially during the initial dose-titration period, probably reflecting its alpha-adrenergic antagonistic properties. Syncope was reported in 0.2% (6/2607) of risperidone-treated patients in Phase 2 and 3 studies in adults with schizophrenia. The risk of orthostatic hypotension and syncope may be minimized by limiting the initial dose to 2 mg total (either once daily or 1 mg twice daily) in normal adults and 0.5 mg twice daily in the elderly and patients with renal or hepatic impairment [see Dosage and Administration(2.1,2.4)]. Monitoring of orthostatic vital signs should be considered in patients for whom this is of concern. A dose reduction should be considered if hypotension occurs. Risperidone should be used with particular caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction or ischemia, heart failure, or conduction abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease, and conditions which would predispose patients to hypotension, e.g., dehydration and hypovolemia. Clinically significant hypotension has been observed with concomitant use of risperidone and antihypertensive medication.

5.8 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

Class Effect: In clinical trial and/or postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia/neutropenia have been reported temporally related to antipsychotic agents, including risperidone. Agranulocytosis has also been reported.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC) and history of drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Patients with a history of a clinically significant low WBC or a drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and discontinuation of risperidone should be considered at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors.

Patients with clinically significant neutropenia should be carefully monitored for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treated promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3) should discontinue risperidoneand have their WBC followed until recovery.

5.9 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

Somnolence was a commonly reported adverse event associated with risperidone treatment, especially when ascertained by direct questioning of patients. This adverse event is dose-related, and in a study utilizing a checklist to detect adverse events, 41% of the high-dose patients (risperidone 16 mg/day) reported somnolence compared to 16% of placebo patients. Direct questioning is more sensitive for detecting adverse events than spontaneous reporting, by which 8% of risperidone 16 mg/day patients and 1% of placebo patients reported somnolence as an adverse event. Since risperidone has the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that risperidone therapy does not affect them adversely.

5.10 Seizures

During premarketing testing in adult patients with schizophrenia, seizures occurred in 0.3% (9/2607) of risperidone-treated patients, two in association with hyponatremia. Risperidone should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures.

5.11 Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use. Aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced Alzheimer’s dementia. Risperidone and other antipsychotic drugs should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia. [See also Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

5.12 Priapism

Priapism has been reported during postmarketing surveillance [see Adverse Reactions (6.8)]. Severe priapism may require surgical intervention.

5.13 Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

A single case of TTP was reported in a 28 year-old female patient receiving oral risperidone in a large, open premarketing experience (approximately 1300 patients). She experienced jaundice, fever, and bruising, but eventually recovered after receiving plasmapheresis. The relationship to risperidone therapy is unknown.

5.14 Body Temperature Regulation

Disruption of body temperature regulation has been attributed to antipsychotic agents. Both hyperthermia and hypothermia have been reported in association with oral risperidone use. Caution is advised when prescribing for patients who will be exposed to temperature extremes.

5.15 Antiemetic Effect

Risperidone has an antiemetic effect in animals; this effect may also occur in humans, and may mask signs and symptoms of overdosage with certain drugs or of conditions such as intestinal obstruction, Reye’s syndrome, and brain tumor.

5.16 Suicide

The possibility of a suicide attempt is inherent in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mania, including children and adolescent patients, and close supervision of high-risk patients should accompany drug therapy.

5.17 Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness

Clinical experience with risperidone in patients with certain concomitant systemic illnesses is limited. Patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies who receive antipsychotics, including risperidone, are reported to have an increased sensitivity to antipsychotic medications. Manifestations of this increased sensitivity have been reported to include confusion, obtundation, postural instability with frequent falls, extrapyramidal symptoms, and clinical features consistent with the neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Caution is advisable in using risperidone in patients with diseases or conditions that could affect metabolism or hemodynamic responses. Risperidone has not been evaluated or used to any appreciable extent in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses were excluded from clinical studies during the product's premarket testing.

Increased plasma concentrations of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone occur in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), and an increase in the free fraction of risperidone is seen in patients with severe hepatic impairment. A lower starting dose should be used in such patients [see Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following are discussed in more detail in other sections of the labeling:

- Increased mortality in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warningand Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Cerebrovascular adverse events, including stroke, in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Tardive dyskinesia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Metabolic changes [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Hyperprolactinemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Orthostatic hypotension [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Leukopenia, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Potential for cognitive and motor impairment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

- Seizures [see Warnings and Precautions (5.10)]

- Dysphagia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11) ]

- Priapism [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)]

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)]

- Disruption of body temperature regulation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14)]

- Antiemetic effect [see Warnings and Precautions (5.15)]

- Suicide [see Warnings and Precautions (5.16)]

- Increased sensitivity in patients with Parkinson’s disease or those with dementia with Lewy bodies [see Warnings and Precautions (5.17)]

- Diseases or conditions that could affect metabolism or hemodynamic responses [see Warnings and Precautions (5.17)]

The most common adverse reactions in clinical trials (≥ 10%) were somnolence, increased appetite, fatigue, insomnia, sedation, parkinsonism, akathisia, vomiting, cough, constipation, nasopharyngitis, drooling, rhinorrhea, dry mouth, abdominal pain upper, dizziness, nausea, anxiety, headache, nasal congestion, rhinitis, tremor, and rash.

The most common adverse reactions that were associated with discontinuation from clinical trials (causing discontinuation in >1% of adults and/or >2% of pediatrics) were nausea, somnolence, sedation, vomiting, dizziness, and akathisia [see Adverse Reactions (6.5)].

The data described in this section are derived from a clinical trial database consisting of 9712 adult and pediatric patients exposed to one or more doses of risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania, or autistic disorder and other psychiatric disorders in pediatrics and elderly patients with dementia. Of these 9712 patients, 2626 were patients who received risperidone while participating in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The conditions and duration of treatment with risperidone varied greatly and included (in overlapping categories) double-blind, fixed- and flexible-dose, placebo- or active-controlled studies and open-label phases of studies, inpatients and outpatients, and short-term (up to 12 weeks) and longer-term (up to 3 years) exposures. Safety was assessed by collecting adverse events and performing physical examinations, vital signs, body weights, laboratory analyses, and ECGs.

Adverse events during exposure to study treatment were obtained by general inquiry and recorded by clinical investigators using their own terminology. Consequently, to provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing adverse events, events were grouped in standardized categories using MedDRA terminology.

Throughout this section, adverse reactions are reported. Adverse reactions are adverse events that were considered to be reasonably associated with the use of risperidone (adverse drug reactions) based on the comprehensive assessment of the available adverse event information. A causal association for risperidone often cannot be reliably established in individual cases. Further, because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in clinical practice. The majority of all adverse reactions were mild to moderate in severity.

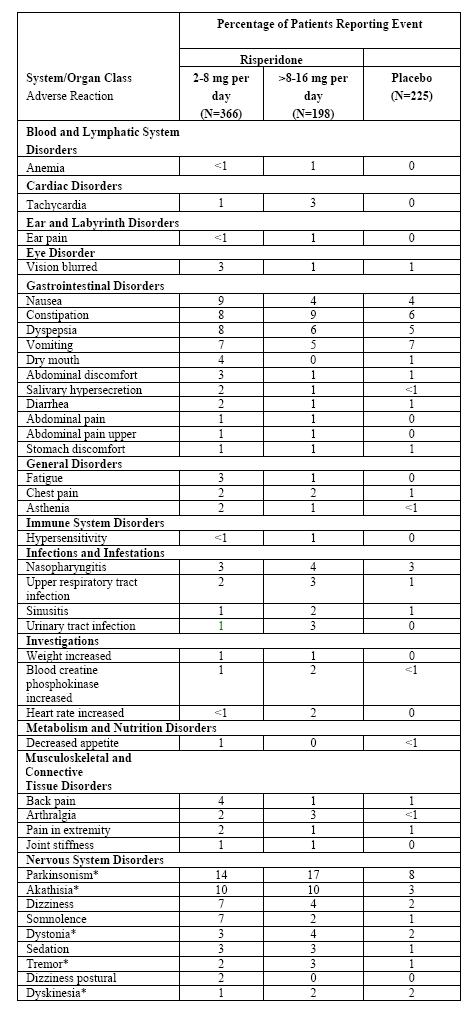

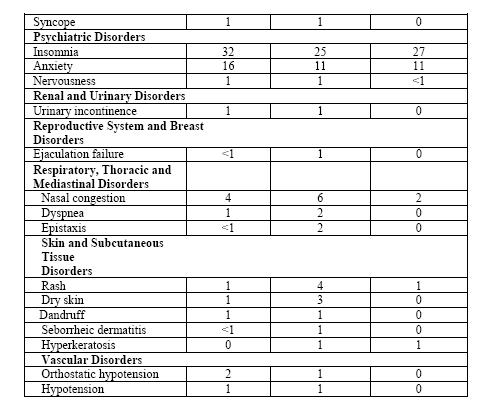

6.1 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials – Schizophrenia

Adult Patients with Schizophrenia

Table 4 lists the adverse reactions reported in 1% or more of risperidone-treated adult patients with schizophrenia in three 4- to 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

Table 4. Adverse Reactions in ≥1% of Risperidone-Treated Adult Patients withSchizophrenia in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials

* Parkinsonism includes extrapyramidal disorder, musculoskeletal stiffness, parkinsonism, cogwheel rigidity, akinesia, bradykinesia, hypokinesia, masked facies, muscle rigidity, and Parkinson’s disease. Akathisia includes akathisia and restlessness. Dystonia includes dystonia, muscle spasms, muscle contractions involuntary, muscle contracture, oculogyration, tongue paralysis. Tremor includes tremor and parkinsonian rest tremor. Dyskinesia includes dyskinesia, muscle twitching, chorea, and choreoathetosis.

Pediatric Patients with Schizophrenia

Table 5 lists the adverse reactions reported in 5% or more of risperidone-treated pediatric patients with schizophrenia in a 6-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Table 5. Adverse Reactions in ≥5% of Risperidone-Treated Pediatric Patients with Schizophrenia in a Double-Blind Trial

Percentage of Patients Reporting Event Risperidone System/Organ ClassAdverse Reaction 1-3 mg per day

(N=55)4-6 mg per day

N=51)Placebo

N=54)Gastrointestinal Disorders Salivary hypersecretion 0 10 2 Nervous System Disorders Parkinsonism* 16 28 11 Sedation 13 8 2 Somnolence 11 4 2 Tremor 11 10 6 Akathisia* 9 10 4 Dizziness 7 14 2 Dystonia* 2 6 0 Psychiatric Disorders Anxiety 7 6 0 * Parkinsonism includes extrapyramidal disorder, muscle rigidity, musculoskeletal stiffness, and hypokinesia. Akathisia includes akathisia and restlessness. Dystonia includes dystonia and oculogyration.

6.2 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials – Bipolar Mania

Adult Patients with Bipolar Mania

Table 6 lists the adverse reactions reported in 1% or more of risperidone-treated adult patients with bipolar mania in four 3-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled monotherapy trials.

Table 6. Adverse Reactions in ≥1% of Risperidone-Treated Adult Patients with Bipolar Mania in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trials

Percentage of Patients Reporting Event System/Organ Class

Adverse ReactionRisperidone

1-6 mg per day

(N=448)Placebo

(N=424)Cardiac Disorders Tachycardia 1 <1 Eye Disorders Vision blurred 2 1 Gastrointestinal Disorders Nausea 5 2 Diarrhea 3 2 Salivary hypersecretion 3 1 Dyspepsia 2 2 Stomach discomfort 2 <1 General Disorders Fatigue 2 1 Asthenia 1 1 Pyrexia 1 1 Infections and Infestations Nasopharyngitis 1 1 Investigations Aspartate aminotransferase increased 1 <1 Nervous System Disorders Parkinsonism* 25 9 Akathisia* 9 3 Tremor* 6 3 Dizziness 6 5 Sedation 6 2 Somnolence 5 2 Dystonia* 5 1 Lethargy 2 1 Dyskinesia* 1 <1 Reproductive System and Breast Disorder Galactorrhea 1 0 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Acne 1 0 * Parkinsonism includes extrapyramidal disorder, parkinsonism, musculoskeletal stiffness, hypokinesia, muscle rigidity, muscle tightness, bradykinesia, cogwheel rigidity. Akathisia includes akathisia and restlessness. Tremor includes tremor and parkinsonian rest tremor. Dystonia includes dystonia, muscle spasms, oculogyration, torticollis. Dyskinesia includes muscle twitching and dyskinesia.

Table 7 lists the adverse reactions reported in 2% or more of risperidone-treated adult patients with bipolar mania in two 3-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjuvant therapy trials.

Table 7. Adverse Reactions in ≥2% of Risperidone-Treated Adult Patients with Bipolar Mania in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Adjuvant Therapy Trials

System/Organ Class

Adverse ReactionPercentage of Patients Reporting Event Risperidone +

Mood Stabilizer

(N=127)Placebo +

Mood Stabilizer

(N=126)Cardiac Disorders Palpitations 2 0 Gastrointestinal Disorders Dyspepsia 9 8 Nausea 6 4 Diarrhea 6 4 Dry mouth 4 4 Vomiting 4 6 Constipation 3 3 Salivary hypersecretion 2 0 General Disorders Chest pain 2 1 Fatigue 2 2 Infections and Infestations Nasopharyngitis 2 3 Urinary tract infection 2 1 Investigations Weight increased 2 2 Nervous System Disorders Parkinsonism* 14 4 Headache 14 15 Akathisia* 8 0 Dizziness 7 2 Sedation 6 3 Tremor 6 2 Somnolence 3 1 Lethargy 2 1 Psychiatric Disorders Insomnia 4 8 Anxiety 3 2 Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders Pharyngolaryngeal pain 5 2 Cough 2 0 * Parkinsonism includes extrapyramidal disorder, hypokinesia and bradykinesia. Akathisia includes hyperkinesia and akathisia.

Pediatric Patients with Bipolar Mania

Table 8 lists the adverse reactions reported in 5% or more of risperidone-treated pediatric patients with bipolar mania in a 3-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Table 8. Adverse Reactions in ≥5% of Risperidone-Treated Pediatric Patients with Bipolar Mania in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials

System/Organ Class

Adverse ReactionPercentage of Patients Reporting Event Risperidone 0.5-2.5 mg per day (N=50) 3-6 mg per day (N=61) Placebo (N=58) Eye Disorders Vision blurred 4 7 0 Gastrointestinal Disorders Abdominal pain upper 16 13 5 Nausea 16 13 7 Vomiting 10 10 5 Diarrhea 8 7 2 Dyspepsia 10 3 2 Stomach discomfort 6 0 2 General Disorders Fatigue 18 30 3 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Increased appetite 4 7 2 Nervous System Disorders Somnolence 22 30 12 Sedation 20 23 7 Dizziness 16 13 5 Parkinsonism* 6 12 3 Dystonia* 6 5 0 Akathisia* 0 8 2 Psychiatric Disorders Anxiety 0 8 3 Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders Pharyngolaryngeal pain 10 3 5 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Rash 0 7 2 * Parkinsonism includes musculoskeletal stiffness, extrapyramidal disorder, bradykinesia, and nuchal rigidity. Dystonia includes dystonia, laryngospasm, and muscle spasms. Akathisia includes restlessness and akathisia.

6.3 Commonly-Observed Adverse Reactions in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials - Autistic Disorder

Table 9 lists the adverse reactions reported in 5% or more of risperidone-treated pediatric patients treated for irritability associated with autistic disorder in two 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

Table 9. Adverse Reactions in ≥5% of Risperidone-Treated Pediatric Patients Treated for Irritability Associated with Autistic Disorder in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials

Percentage of Patients Reporting Event Sytem/Organ Class

Adverse ReacitonRisperidone

0.5-4.0 mg per day

(N=76)Placebo

(N=80)Cardiac Disorders Tachycardia 5 0 Gastrointestinal Disorders Vomiting 25 21 Constipation 21 8 Dry mouth 15 6 Salivary hypersecretion 9 0 Nausea 8 6 General Disorders Fatigue 42 13 Feeling abnormal 5 0 Infections and Infestations Nasopharyngitis 21 10 Rhinitis 13 10 Upper respiratory tract infection 8 3 Investigations Weight increased 5 0 Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders Increased appetite 47 19 Nervous System Disorders Somnolence 49 18 Sedation 29 3 Drooling 16 5 Tremor 12 1 Parkinsonism* 11 1 Dizziness 9 3 Dyskinesia 7 3 Lethargy 5 3 Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders Cough 24 18 Rhinorrhea 16 13 Nasal congestion 13 5 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders Rash 11 8 *Parkinsonism includes musculoskeletal stiffness, extrapyramidal disorder, muscle rigidity, cogwheel rigidity, and muscle tightness.

In another study with patients treated for irritability associated with autistic disorder, headache (6%), epistaxis (6%) and pyrexia (6%) were also observed in risperidone treated pediatric subjects.

6.4 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Risperidone

The following adverse reactions occurred in < 1% of the adult patients and in < 5% of the pediatric patients treated with risperidone in the above double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial data sets. In addition, the following also includes adverse reactions reported in risperidone-treated patients who participated in other studies, including double-blind, active-controlled and open-label studies in schizophrenia and bipolar mania studies in pediatric patients with psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia, bipolar mania, or autistic disorder and studies in elderly patients with dementia.

Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: granulocytopenia, neutropenia

Cardiac Disorders: sinus bradycardia, sinus tachycardia, atrioventricular block first degree, bundle branch block left, bundle branch block right, atrioventricular block

Ear and Labyrinth Disorders: tinnitus

Endocrine Disorders: hyperprolactinemia

Eye Disorders: ocular hyperemia, eye discharge, conjunctivitis, eye rolling, eyelid edema, eye swelling, eyelid margin crusting, dry eye, lacrimation increased, photophobia, glaucoma, visual acuity reduced

Gastrointestinal Disorders: dysphagia, fecaloma, fecal incontinence, gastritis, lip swelling, cheilitis, aptyalism

General Disorders: edema peripheral, thirst, gait disturbance, influenza-like illness, pitting edema, edema, chills, sluggishness, malaise, chest discomfort, face edema, discomfort, generalized edema, drug withdrawal syndrome, peripheral coldness

Immune System Disorders: drug hypersensitivity

Infections and Infestations: pneumonia, influenza, ear infection, viral infection, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, bronchitis, eye infection, localized infection, cystitis, cellulitis, otitis media, onychomycosis, acarodermatitis, bronchopneumonia, respiratory tract infection, tracheobronchitis, otitis media chronic

Investigations: body temperature increased, blood prolactin increased, alanine aminotransferase increased, electrocardiogram abnormal, eosinophil count increased, white blood cell count decreased, blood glucose increased, hemoglobin decreased, hematocrit decreased, body temperature decreased, blood pressure decreased, transaminases increased

Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders: polydipsia, anorexia

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: joint swelling, musculoskeletal chest pain, posture abormal, myalgia, neck pain, muscular weakness, rhabdomyolysis

Nervous System Disorders: balance disorder, disturbance in attention, dysarthria, unresponsive to stimuli, depressed level of consciousness, movement disorder, hypersomnia, transient ischemic attack, coordination abnormal, cerebrovascular accident, speech disorder, loss of consciousness, hypoesthesia, tardive dyskinesia, cerebral ischemia, cerebrovascular disorder, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, diabetic coma, head titubation

Psychiatric Disorders: agitation, blunted affect, confusional state, middle insomnia, sleep disorder, listlessness, libido decreased, anorgasmia

Renal and Urinary Disorders: enuresis, dysuria, pollakiuria

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: menstruation irregular, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, vaginal discharge, menstrual disorder, erectile dysfunction, retrograde ejaculation, ejaculation disorder, sexual dysfunction, breast enlargement

Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders: wheezing, pneumonia aspiration, sinus congestion, dysphonia, productive cough, pulmonary congestion, respiratory tract congestion, rales, respiratory disorder, hyperventilation, nasal edema

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: erythema, skin discoloration, skin lesion, pruritus, skin disorder, rash erythematous, rash papular, rash generalized, rash maculopapular

Vascular Disorders: flushing

Additional Adverse Reactions Reported with Risperidone Injection

The following is a list of additional adverse reactions that have been reported during the premarketing evaluation of risperidone injection, regardless of frequency of occurrence:

Cardiac Disorders: bradycardia

Ear and Labyrinth Disorders: vertigo

Eye Disorders: blepharospasm

Gastrointestinal Disorders: toothache, tongue spasm

General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions: pain

Infections and Infestations: lower respiratory tract infection, infection, gastroenteritis, subcutaneous abscess

Injury and Poisoning: fall

Investigations: weight decreased, gamma-glutamyltransferase increased, hepatic enzyme increased

Musculoskeletal, Connective Tissue, and Bone Disorders: buttock pain

Nervous System Disorders: convulsion, paresthesia

Psychiatric Disorders: depression

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: eczema

Vascular Disorders: hypertension

6.5 Discontinuations Due to Adverse Reactions

Schizophrenia - Adults

Approximately 7% (39/564) of risperidone-treated patients in double-blind, placebocontrolled trials discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, compared with 4% (10/225) who were receiving placebo. The adverse reactions associated with discontinuation in 2 or more risperidone -treated patients were:

Table 10. Adverse Reactions Associated with Discontinuation in 2 or More Risperidone-Treated Adult Patients in Schizophrenia Trials

Risperidone Adverse Reaction 2-8 mg/day

(N=366)>8-16 mg/day

(N=198)Placebo

(N=225)Dizziness 1.4% 1.0% 0% Nausea 1.4% 0% 0% Vomiting 0.8% 0% 0% Parkinsonism 0.8% 0% 0% Somnolence 0.8% 0% 0% Dystonia 0.5% 0% 0% Agitation 0.5% 0% 0% Abdominal pain 0.5% 0% 0% Orthostatic hypotension 0.3% 0.5% 0% Akathisia 0.3% 2.0% 0% Discontinuation for extrapyramidal symptoms (including Parkinsonism, akathisia, dystonia, and tardive dyskinesia) was 1% in placebo-treated patients, and 3.4% in active control-treated patients in a double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial.

Schizophrenia - Pediatrics

Approximately 7% (7/106), of risperidone-treated patients discontinued treatment due to an adverse event in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, compared with 4% (2/54) placebo-treated patients. The adverse reactions associated with discontinuation for at least one risperidone-treated patient were dizziness (2%), somnolence (1%), sedation (1%), lethargy (1%), anxiety (1%), balance disorder (1%), hypotension (1%), and palpitation (1%).

Bipolar Mania - Adults

In double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with risperidone as monotherapy, approximately 6% (25/448) of risperidone-treated patients discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, compared with approximately 5% (19/424) of placebo-treated patients. The adverse reactions associated with discontinuation in risperidone-treated patients were:

Table 11. Adverse Reactions Associated With Discontinuation in 2 or More Risperidone-Treated Adult Patients in Bipolar Mania Clinical Trials

Adverse Reaction Risperidone

1-6 mg/day

(N=448)Placebo

(N=424)Parkinsonism 0.4% 0% Lethargy 0.2% 0% Dizziness 0.2% 0% Alanine aminotransferace increased 0.2% 0.2% Aspartate aminotransferace increased 0.2% 0.2% Bipolar Mania - Pediatrics

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 12% (13/111) of risperidone-treated patients discontinued due to an adverse event, compared with 7% (4/58) of placebo-treated patients. The adverse reactions associated with discontinuation in more than one risperidone-treated pediatric patient were nausea (3%), somnolence (2%), sedation (2%), and vomiting (2%).

Autistic Disorder - Pediatrics

In the two 8-week, placebo-controlled trials in pediatric patients treated for irritability associated with autistic disorder (n = 156), one risperidone -treated patient discontinued due to an adverse reaction (Parkinsonism), and one placebo-treated patient discontinued due to an adverse event.

6.6 Dose Dependency of Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Data from two fixed-dose trials in adults with schizophrenia provided evidence of dose- relatedness for extrapyramidal symptoms associated with risperidone treatment.

Two methods were used to measure extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) in an 8-week trial comparing 4 fixed doses of risperidone (2, 6, 10, and 16 mg/day), including (1) a Parkinsonism score (mean change from baseline) from the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, and (2) incidence of spontaneous complaints of EPS:

Dose Groups Placebo Risperidone

2 mgRisperidone

6 mgRisperidone

10 mgRisperidone

16 mgParkinsonism 1.2 0.9 1.8 2.4 2.6 EPS Incidence 13% 17% 21% 21% 35% Similar methods were used to measure extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) in an 8-week trial comparing 5 fixed doses of risperidone (1, 4, 8, 12, and 16 mg/day):

Dose Groups Risperidone

1 mgRisperidone

4 mgRisperidone

8 mgRisperidone

12 mgRisperidone

16 mgParkinsonism 0.6 1.7 2.4 2.9 4.1 EPS Incidence 7% 12% 17% 18% 20% Dystonia

Class Effect: Symptoms of dystonia, prolonged abnormal contractions of muscle groups, may occur in susceptible individuals during the first few days of treatment. Dystonic symptoms include: spasm of the neck muscles, sometimes progressing to tightness of the throat, swallowing difficulty, difficulty breathing, and/or protrusion of the tongue. While these symptoms can occur at low doses, they occur more frequently and with greater severity with high potency and at higher doses of first generation antipsychotic drugs. An elevated risk of acute dystonia is observed in males and younger age groups.

Other Adverse Reactions

Adverse event data elicited by a checklist for side effects from a large study comparing 5 fixed doses of risperidone (1, 4, 8, 12, and 16 mg/day) were explored for dose-relatedness of adverse events. A Cochran-Armitage Test for trend in these data revealed a positive trend (p<0.05) for the following adverse reactions: somnolence, vision abnormal, dizziness, palpitations, weight increase, erectile dysfunction, ejaculation disorder, sexual function abnormal, fatigue, and skin discoloration.

6.7 Changes in ECG

Between-group comparisons for pooled placebo-controlled trials in adults revealed no statistically significant differences between risperidone and placebo in mean changes from baseline in ECG parameters, including QT, QTc, and PR intervals, and heart rate. When all risperidone doses were pooled from randomized controlled trials in several indications, there was a mean increase in heart rate of 1 beat per minute compared to no change for placebo patients. In short-term schizophrenia trials, higher doses of risperidone (8-16 mg/day) were associated with a higher mean increase in heart rate compared to placebo (4-6 beats per minute). In pooled placebo-controlled acute mania trials in adults, there were small decreases in mean heart rate, similar among all treatment groups.

In the two placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with autistic disorder (aged 5 to 16 years) mean changes in heart rate were an increase of 8.4 beats per minute in the risperidone groups and 6.5 beats per minute in the placebo group. There were no other notable ECG changes.

In a placebo-controlled acute mania trial in children and adolescents (aged 10 to 17 years), there were no significant changes in ECG parameters, other than the effect of risperidone to transiently increase pulse rate (< 6 beats per minute). In two controlled schizophrenia trials in adolescents (aged 13 to 17 years), there were no clinically meaningful changes in ECG parameters including corrected QT intervals between treatment groups or within treatment groups over time.

6.8 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of risperidone; because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not possible to reliably estimate their frequency: agranulocytosis, alopecia, anaphylactic reaction, angioedema, atrial fibrillation, blood cholesterol increased, blood triglycerides increased, diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with impaired glucose metabolism, drug withdrawal syndrome neonatal, dysgeusia, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, intestinal obstruction, jaundice, mania, pancreatitis, priapism, QT prolongation, sleep apnea syndrome, thrombocytopenia, urinary retention, and water intoxication.

Other adverse events reported since market introduction, which were temporally related to risperidone but not necessarily causally related, include the following: pituitary adenoma, pulmonary embolism, precocious puberty, cardiopulmonary arrest, and sudden death.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Centrally-Acting Drugs and Alcohol

Given the primary CNS effects of risperidone, caution should be used when risperidone is taken in combination with other centrally-acting drugs and alcohol

7.2 Drugs with Hypotensive Effects

Because of its potential for inducing hypotension, risperidone may enhance the hypotensive effects of other therapeutic agents with this potential.

7.3 Levodopa and Dopamine Agonists

Risperidone may antagonize the effects of levodopa and dopamine agonists.

7.4 Amitriptyline

Amitriptyline did not affect the pharmacokinetics of risperidone or risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone combined.

7.5 Cimetidine and Ranitidine

Cimetidine and ranitidine increased the bioavailability of risperidone by 64% and 26%, respectively. However, cimetidine did not affect the AUC of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone combined, whereas ranitidine increased the AUC of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone combined by 20%.

7.6 Clozapine

Chronic administration of clozapine with risperidone may decrease the clearance of risperidone.

7.7 Lithium

Repeated oral doses of risperidone (3 mg twice daily) did not affect the exposure (AUC) or peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of lithium (n=13).

7.8 Valproate

Repeated oral doses of risperidone (4 mg once daily) did not affect the pre-dose or average plasma concentrations and exposure (AUC) of valproate (1000 mg/day in three divided doses) compared to placebo (n=21). However, there was a 20% increase in valproate peak plasma concentration (Cmax) after concomitant administration of risperidone.

7.9 Digoxin

Risperidone (0.25 mg twice daily) did not show a clinically relevant effect on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin.

7.10 Drugs That Inhibit CYP 2D6 and Other CYP Isozymes

Risperidone is metabolized to 9-hydroxyrisperidone by CYP 2D6, an enzyme that is polymorphic in the population and that can be inhibited by a variety of psychotropic and other drugs [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Drug interactions that reduce the metabolism of risperidone to 9-hydroxyrisperidone would increase the plasma concentrations of risperidone and lower the concentrations of 9-hydroxyrisperidone. Analysis of clinical studies involving a modest number of poor metabolizers ((n≅70) does not suggest that poor and extensive metabolizers have different rates of adverse effects. No comparison of effectiveness in the two groups has been made.

In vitro studies showed that drugs metabolized by other CYP isozymes, including 1A1, 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, and 3A4, are only weak inhibitors of risperidone metabolism.

Fluoxetine and Paroxetine

Fluoxetine (20 mg once daily) and paroxetine (20 mg once daily) have been shown to increase the plasma concentration of risperidone 2.5-2.8 fold and 3-9 fold, respectively. Fluoxetine did not affect the plasma concentration of 9-hydroxyrisperidone. Paroxetine lowered the concentration of 9-hydroxyrisperidone by about 10%. When either concomitant fluoxetine or paroxetine is initiated or discontinued, the physician should re-evaluate the dosing of risperidone. The effects of discontinuation of concomitant fluoxetine or paroxetine therapy on the pharmacokinetics of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone have not been studied.

7.11 Carbamazepine and Other Enzyme Inducers

Carbamazepine co-administration decreased the steady-state plasma concentrations of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone by about 50%. Plasma concentrations of carbamazepine did not appear to be affected. The dose of risperidone may need to be titrated accordingly for patients receiving carbamazepine, particularly during initiation or discontinuation of carbamazepine therapy. Co-administration of other known enzyme inducers (e.g., phenytoin, rifampin, and phenobarbital) with risperidone may cause similar decreases in the combined plasma concentrations of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone, which could lead to decreased efficacy of risperidone treatment.

7.12 Drugs Metabolized by CYP 2D6

In vitro studies indicate that risperidone is a relatively weak inhibitor of CYP 2D6. Therefore, risperidone is not expected to substantially inhibit the clearance of drugs that are metabolized by this enzymatic pathway. In drug interaction studies, risperidone did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of donepezil and galantamine, which are metabolized by CYP 2D6.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C.

The teratogenic potential of risperidone was studied in three Segment II studies in Sprague- Dawley and Wistar rats (0.63-10 mg/kg or 0.4 to 6 times the maximum recommended human dose [MRHD] on a mg/m2 basis) and in one Segment II study in New Zealand rabbits (0.31-5 mg/kg or 0.4 to 6 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis). The incidence of malformations was not increased compared to control in offspring of rats or rabbits given 0.4 to 6 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. In three reproductive studies in rats (two Segment III and a multigenerational study), there was an increase in pup deaths during the first 4 days of lactation at doses of 0.16-5 mg/kg or 0.1 to 3 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. It is not known whether these deaths were due to a direct effect on the fetuses or pups or to effects on the dams.

There was no no-effect dose for increased rat pup mortality. In one Segment III study, there was an increase in stillborn rat pups at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg or 1.5 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. In a cross-fostering study in Wistar rats, toxic effects on the fetus or pups, as evidenced by a decrease in the number of live pups and an increase in the number of dead pups at birth (Day 0), and a decrease in birth weight in pups of drug-treated dams were observed. In addition, there was an increase in deaths by Day 1 among pups of drug-treated dams, regardless of whether or not the pups were cross-fostered. Risperidone also appeared to impair maternal behavior in that pup body weight gain and survival (from Day 1 to 4 of lactation) were reduced in pups born to control but reared by drug-treated dams. These effects were all noted at the one dose of risperidone tested, i.e., 5 mg/kg or 3 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

Placental transfer of risperidone occurs in rat pups. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. However, there was one report of a case of agenesis of the corpus callosum in an infant exposed to risperidone in utero. The causal relationship to risperidone therapy is unknown.

Non-Teratogenic Effects

Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs (including Risperdione) during the third trimester of pregnancy are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery. There have been reports of agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, and feeding disorder in these neonates. These complications have varied in severity; while in some cases symptoms have been self-limited, in other cases neonates have required intensive care unit support and prolonged hospitalization.

Risperidone should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

In animal studies, risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone are excreted in milk. Risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone are also excreted in human breast milk. Therefore, women receiving risperidone should not breast-feed.

8.4 Pediatric Use

The efficacy and safety of risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia were demonstrated in 417 adolescents, aged 13 to 17 years, in two short-term (6 and 8 weeks, respectively) double-blind controlled trials [see Indications and Usage (1.1), Adverse Reactions (6.1), and Clinical Studies (14.1)].Additional safety and efficacy information was also assessed in one long-term (6-month) open-label extension study in 284 of these adolescent patients with schizophrenia.

Safety and effectiveness of risperidone in children less than 13 years of age with schizophrenia have not been established.

The efficacy and safety of risperidonein the short-term treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder in 169 children and adolescent patients, aged 10 to 17 years, were demonstrated in one double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week trial [see Indications and Usage (1.2), Adverse Reactions (6.2), and Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Safety and effectiveness of risperidone in children less than 10 years of age with bipolar disorder have not been established.