ESCITALOPRAM tablet, film coated

Escitalopram by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Escitalopram by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by RedPharm Drug, Inc., EPM Packaging, Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNINGS: SUICIDALITY AND ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of Escitalopram or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. Escitalopram is not approved for use in pediatric patients less than 12 years of age. [See Warnings and Precautions: Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk ( 5.1), Patient Counseling Information: Information for Patients ( 17.1), and Use in Specific Populations: Pediatric Use ( 8.4)].

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Major Depressive Disorder

Escitalopram is indicated for the acute and maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder in adults and in adolescents 12 to 17 years of age [ see Clinical Studies ( 14.1) ].

A major depressive episode (DSM-IV) implies a prominent and relatively persistent (nearly every day for at least 2 weeks) depressed or dysphoric mood that usually interferes with daily functioning, and includes at least five of the following nine symptoms: depressed mood, loss of interest in usual activities, significant change in weight and/or appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, increased fatigue, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, slowed thinking or impaired concentration, a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation.

1.2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Escitalopram is indicated for the acute treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in adults [ see Clinical Studies ( 14.2) ].

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (DSM-IV) is characterized by excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation) that is persistent for at least 6 months and which the person finds difficult to control. It must be associated with at least 3 of the following symptoms: restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge, being easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating or mind going blank, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance.

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Escitalopram tablets should be administered once daily, in the morning or evening, with or without food.

2.1 Major Depressive Disorder

Initial Treatment

Adolescents

The recommended dose of Escitalopram tablets is 10 mg once daily. A flexible-dose trial of Escitalopram (10 to 20 mg/day) demonstrated the effectiveness of Escitalopram [ see Clinical Studies ( 14.1) ]. If the dose is increased to 20 mg, this should occur after a minimum of three weeks.

Adults

The recommended dose of Escitalopram tablets is 10 mg once daily. A fixed-dose trial of Escitalopram demonstrated the effectiveness of both 10 mg and 20 mg of Escitalopram, but failed to demonstrate a greater benefit of 20 mg over 10 mg [ see Clinical Studies ( 14.1) ]. If the dose is increased to 20 mg, this should occur after a minimum of one week.

Maintenance Treatment

It is generally agreed that acute episodes of major depressive disorder require several months or longer of sustained pharmacological therapy beyond response to the acute episode. Systematic evaluation of continuing Escitalopram 10 or 20 mg/day in adults patients with major depressive disorder who responded while taking Escitalopram during an 8-week, acute-treatment phase demonstrated a benefit of such maintenance treatment [see Clinical Studies ( 14.1)]. Nevertheless, the physician who elects to use Escitalopram tablets for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment.

2.2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Maintenance Treatment

Generalized anxiety disorder is recognized as a chronic condition. The efficacy of Escitalopram in the treatment of GAD beyond 8 weeks has not been systematically studied. The physician who elects to use Escitalopram tablets for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.

2.3 Special Populations

10 mg/day is the recommended dose for most elderly patients and patients with hepatic impairment.

No dosage adjustment is necessary for patients with mild or moderate renal impairment. Escitalopram should be used with caution in patients with severe renal impairment.

2.4 Discontinuation of Treatment with Escitalopram tablets

Symptoms associated with discontinuation of Escitalopram tablets and other SSRIs and SNRIs have been reported [ see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.3) ]. Patients should be monitored for these symptoms when discontinuing treatment. A gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate.

2.5 Switching a Patient To or From a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) Intended to Treat Psychiatric Disorders

At least 14 days should elapse between discontinuation of an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders and initiation of therapy with Escitalopram tablets. Conversely, at least 14 days should be allowed after stopping Escitalopram tablets before starting an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders [ see Contraindications ( 4.1)].

2.6 Use of Escitalopram with Other MAOIs such as Linezolid or Methylene Blue

Do not start Escitalopram tablets in a patient who is being treated with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue because there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. In a patient who requires more urgent treatment of a psychiatric condition, other interventions, including hospitalization, should be considered [ see Contraindications ( 4.1)].

In some cases, a patient already receiving Escitalopram tablets therapy may require urgent treatment with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. If acceptable alternatives to linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are not available and the potential benefits of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are judged to outweigh the risks of serotonin syndrome in a particular patient, Escitalopram tablets should be stopped promptly, and linezolid or intravenous methylene blue can be administered. The patient should be monitored for symptoms of serotonin syndrome for 2 weeks or until 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue, whichever comes first. Therapy with Escitalopram tablets may be resumed 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue [ see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2)].

The risk of administering methylene blue by non-intravenous routes (such as oral tablets or by local injection) or in intravenous doses much lower than 1 mg/kg with Escitalopram is unclear. The clinician should, nevertheless, be aware of the possibility of emergent symptoms of serotonin syndrome with such use [ see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2)].

-

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

3.1 Tablets

Escitalopram Tablets, USP are film-coated, round tablets containing escitalopram oxalate in strengths equivalent to 5 mg, 10 mg and 20 mg escitalopram base. The 10 and 20 mg tablets are scored. Imprinted with "P" and either "5", “10”, or “20” on same side according to their respective strengths.

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

4.1 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

The use of MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders with Escitalopram tablets or within 14 days of stopping treatment with Escitalopram tablets is contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. The use of Escitalopram tablets within 14 days of stopping an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders is also contraindicated [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.5), and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) ].

Starting Escitalopram tablets in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue is also contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.6), and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2)].

4.2 Pimozide

Concomitant use in patients taking pimozide is contraindicated [ see Drug Interactions ( 7.10) ].

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long-standing concern, however, that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment. Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and others) showed that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18-24) with major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Short term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short-term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4400 patients. The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short-term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger patients for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk differences (drug vs. placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1000 patients treated) are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Age Range

Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1000 Patients Treated

Increases Compared to Placebo

<18

14 additional cases

18-24

5 additional cases

Decreases Compared to Placebo

25-64

1 fewer case

≥65

6 fewer cases

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient's presenting symptoms.

If the decision has been made to discontinue treatment, medication should be tapered, as rapidly as is feasible, but with recognition that abrupt discontinuation can be associated with certain symptoms [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.4) ].

Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder or other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to health care providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers [ see also Patient Counseling Information ( 17.1) ]. Prescriptions for Escitalopram should be written for the smallest quantity of tablets consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

Screening Patients for Bipolar Disorder

A major depressive episode may be the initial presentation of bipolar disorder. It is generally believed (though not established in controlled trials) that treating such an episode with an antidepressant alone may increase the likelihood of precipitation of a mixed/manic episode in patients at risk for bipolar disorder. Whether any of the symptoms described above represent such a conversion is unknown. However, prior to initiating treatment with an antidepressant, patients with depressive symptoms should be adequately screened to determine if they are at risk for bipolar disorder; such screening should include a detailed psychiatric history, including a family history of suicide, bipolar disorder, and depression. It should be noted that Escitalopram is not approved for use in treating bipolar depression.

5.2 Serotonin Syndrome

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome has been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs, including Escitalopram, alone but particularly with concomitant use of other serotonergic drugs (including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, amphetamines, and St. John’s Wort) and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin (in particular, MAOIs, both those intended to treat psychiatric disorders and also others, such as linezolid and intravenous methylene blue).

Serotonin syndrome symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, delirium, and coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, dizziness, diaphoresis, flushing, hyperthermia), neuromuscular symptoms (e.g., tremor, rigidity, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, incoordination) seizures, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Patients should be monitored for the emergence of serotonin syndrome.

- The concomitant use of Escitalopram with MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders is contraindicated. Escitalopram should also not be started in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. All reports with methylene blue that provided information on the route of administration involved intravenous administration in the dose range of 1 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg. No reports involved the administration of methylene blue by other routes (such as oral tablets or local tissue injection) or at lower doses. There may be circumstances when it is necessary to initiate treatment with an MAOI such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue in a patient taking Escitalopram. Escitalopram should be discontinued before initiating treatment with the MAOI [ see Contraindications ( 4.1) and Dosage and Administration ( 2.5 and 2.6) ].

If concomitant use of Escitalopram with other serotonergic drugs including, triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, buspirone, tryptophan, amphetamine, and St. John’s Wort is clinically warranted, patients should be made aware of a potential increased risk for serotonin syndrome, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases.

Treatment with Escitalopram and any concomitant serotonergic agents, should be discontinued immediately if the above events occur and supportive symptomatic treatment should be initiated.

5.3 Discontinuation of Treatment with Escitalopram tablets

During marketing of Escitalopram and other SSRIs and SNRIs (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), there have been spontaneous reports of adverse events occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, and hypomania. While these events are generally self-limiting, there have been reports of serious discontinuation symptoms.

Patients should be monitored for these symptoms when discontinuing treatment with Escitalopram. A gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.4) ].

5.4 Seizures

Although anticonvulsant effects of racemic citalopram have been observed in animal studies, Escitalopram has not been systematically evaluated in patients with a seizure disorder. These patients were excluded from clinical studies during the product's premarketing testing. In clinical trials of Escitalopram, cases of convulsion have been reported in association with Escitalopram treatment. Like other drugs effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder, Escitalopram should be introduced with care in patients with a history of seizure disorder.

5.5 Activation of Mania/Hypomania

In placebo-controlled trials of Escitalopram in major depressive disorder, activation of mania/hypomania was reported in one (0.1%) of 715 patients treated with Escitalopram and in none of the 592 patients treated with placebo. One additional case of hypomania has been reported in association with Escitalopram treatment. Activation of mania/hypomania has also been reported in a small proportion of patients with major affective disorders treated with racemic citalopram and other marketed drugs effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder. As with all drugs effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder, Escitalopram should be used cautiously in patients with a history of mania.

5.6 Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia may occur as a result of treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs, including Escitalopram. In many cases, this hyponatremia appears to be the result of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and was reversible when Escitalopram was discontinued. Cases with serum sodium lower than 110 mmol/L have been reported. Elderly patients may be at greater risk of developing hyponatremia with SSRIs and SNRIs. Also, patients taking diuretics or who are otherwise volume depleted may be at greater risk [ see Geriatric Use ( 8.5)]. Discontinuation of Escitalopram should be considered in patients with symptomatic hyponatremia and appropriate medical intervention should be instituted.

Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia include headache, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, weakness, and unsteadiness, which may lead to falls. Signs and symptoms associated with more severe and/or acute cases have included hallucination, syncope, seizure, coma, respiratory arrest, and death.

5.7 Abnormal Bleeding

SSRIs and SNRIs, including Escitalopram, may increase the risk of bleeding events. Concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin, and other anticoagulants may add to the risk. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding events related to SSRIs and SNRIs use have ranged from ecchymoses, hematomas, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages.

Patients should be cautioned about the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of Escitalopram and NSAIDs, aspirin, or other drugs that affect coagulation.

5.8 Interference with Cognitive and Motor Performance

In a study in normal volunteers, Escitalopram 10 mg/day did not produce impairment of intellectual function or psychomotor performance. Because any psychoactive drug may impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, however, patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that Escitalopram therapy does not affect their ability to engage in such activities.

5.9 Angle Closure Glaucoma

Angle Closure Glaucoma: The pupillary dilation that occurs following use of many antidepressant drugs including Lexapro may trigger an angle closure attack in a patient with anatomically narrow angles who does not have a patent iridectomy.

5.10 Use in Patients with Concomitant Illness

Clinical experience with Escitalopram in patients with certain concomitant systemic illnesses is limited. Caution is advisable in using Escitalopram in patients with diseases or conditions that produce altered metabolism or hemodynamic responses.

Escitalopram has not been systematically evaluated in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses were generally excluded from clinical studies during the product's premarketing testing.

In subjects with hepatic impairment, clearance of racemic citalopram was decreased and plasma concentrations were increased. The recommended dose of Escitalopram in hepatically impaired patients is 10 mg/day [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.3) ].

Because escitalopram is extensively metabolized, excretion of unchanged drug in urine is a minor route of elimination. Until adequate numbers of patients with severe renal impairment have been evaluated during chronic treatment with Escitalopram, however, it should be used with caution in such patients [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.3) ].

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Solco Healthcare US, LLC at 1-866-257-2597 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical studies are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical studies of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical studies of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Clinical Trial Data Sources

Pediatrics (6 -17 years)

Adverse events were collected in 576 pediatric patients (286 Escitalopram, 290 placebo) with major depressive disorder in double-blind placebo-controlled studies. Safety and effectiveness of Escitalopram in pediatric patients less than 12 years of age has not been established.

Adults

Adverse events information for Escitalopram was collected from 715 patients with major depressive disorder who were exposed to escitalopram and from 592 patients who were exposed to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. An additional 284 patients with major depressive disorder were newly exposed to escitalopram in open-label trials. The adverse event information for Escitalopram in patients with GAD was collected from 429 patients exposed to escitalopram and from 427 patients exposed to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

Adverse events during exposure were obtained primarily by general inquiry and recorded by clinical investigators using terminology of their own choosing. Consequently, it is not possible to provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing adverse events without first grouping similar types of events into a smaller number of standardized event categories. In the tables and tabulations that follow, standard World Health Organization (WHO) terminology has been used to classify reported adverse events.

The stated frequencies of adverse reactions represent the proportion of individuals who experienced, at least once, a treatment emergent adverse event of the type listed. An event was considered treatment-emergent if it occurred for the first time or worsened while receiving therapy following baseline evaluation.

Adverse Events Associated with Discontinuation of Treatment

Major Depressive Disorder

Pediatrics (6 -17 years)

Adverse events were associated with discontinuation of 3.5% of 286 patients receiving Escitalopram and 1% of 290 patients receiving placebo. The most common adverse event (incidence at least 1% for Escitalopram and greater than placebo) associated with discontinuation was insomnia (1% Escitalopram, 0% placebo).

Adults

Among the 715 depressed patients who received Escitalopram in placebo-controlled trials, 6% discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, as compared to 2% of 592 patients receiving placebo. In two fixed-dose studies, the rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients receiving 10 mg/day Escitalopram was not significantly different from the rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients receiving placebo. The rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients assigned to a fixed dose of 20 mg/day Escitalopram was 10%, which was significantly different from the rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients receiving 10 mg/day Escitalopram (4%) and placebo (3%). Adverse events that were associated with the discontinuation of at least 1% of patients treated with Escitalopram, and for which the rate was at least twice that of placebo, were nausea (2%) and ejaculation disorder (2% of male patients).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Adults

Among the 429 GAD patients who received Escitalopram 10-20 mg/day in placebo-controlled trials, 8% discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, as compared to 4% of 427 patients receiving placebo. Adverse events that were associated with the discontinuation of at least 1% of patients treated with Escitalopram, and for which the rate was at least twice the placebo rate, were nausea (2%), insomnia (1%), and fatigue (1%).

Incidence of Adverse Reactions in Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials

Major Depressive Disorder

Pediatrics (6 -17 years)

The overall profile of adverse reactions in pediatric patients was generally similar to that seen in adult studies, as shown in Table 2. However, the following adverse reactions (excluding those which appear in Table 2 and those for which the coded terms were uninformative or misleading) were reported at an incidence of at least 2% for Escitalopram and greater than placebo: back pain, urinary tract infection, vomiting, and nasal congestion.

Adults

The most commonly observed adverse reactions in Escitalopram patients (incidence of approximately 5% or greater and approximately twice the incidence in placebo patients) were insomnia, ejaculation disorder (primarily ejaculatory delay), nausea, sweating increased, fatigue, and somnolence.

Table 2 enumerates the incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of treatment-emergent adverse events that occurred among 715 depressed patients who received Escitalopram at doses ranging from 10 to 20 mg/day in placebo-controlled trials. Events included are those occurring in 2% or more of patients treated with Escitalopram and for which the incidence in patients treated with Escitalopram was greater than the incidence in placebo-treated patients.

TABLE 2 Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions observed with a frequency of ≥ 2% and greater than placebo for Major Depressive Disorder 1Primarily ejaculatory delay. 2Denominator used was for males only (N=225 Escitalopram; N=188 placebo). 3Denominator used was for females only (N=490 Escitalopram; N=404 placebo). Adverse Reaction

Escitalopram

Placebo

(N=715)

%(N=592)

%Autonomic Nervous System Disorders

Dry Mouth

6%

5%

Sweating Increased

5%

2%

Central & Peripheral Nervous System Disorders

Dizziness

5%

3%

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Nausea

15%

7%

Diarrhea

8%

5%

Constipation

3%

1%

Indigestion

3%

1%

Abdominal Pain

2%

1%

General

Influenza-like Symptoms

5%

4%

Fatigue

5%

2%

Psychiatric Disorders

Insomnia

9%

4%

Somnolence

6%

2%

Appetite Decreased

3%

1%

Libido Decreased

3%

1%

Respiratory System Disorders

Rhinitis

5%

- 4%

Sinusitis

3%

2%

Urogenital

Ejaculation Disorder 1,2

9%

<1%

Impotence 2

3%

<1%

Anorgasmia 3

2%

<1%

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Adults

The most commonly observed adverse reactions in Escitalopram patients (incidence of approximately 5% or greater and approximately twice the incidence in placebo patients) were nausea, ejaculation disorder (primarily ejaculatory delay), insomnia, fatigue, decreased libido, and anorgasmia.

Table 3 enumerates the incidence, rounded to the nearest percent of treatment-emergent adverse events that occurred among 429 GAD patients who received Escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/day in placebo-controlled trials. Events included are those occurring in 2% or more of patients treated with Escitalopram and for which the incidence in patients treated with Escitalopram was greater than the incidence in placebo-treated patients.

TABLE 3 Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions observed with a frequency of ≥ 2% and greater than placebo for Generalized Anxiety Disorder 1Primarily ejaculatory delay. 2Denominator used was for males only (N=182 Escitalopram; N=195 placebo). 3Denominator used was for females only (N=247 Escitalopram; N=232 placebo). Adverse Reaction

Escitalopram

Placebo

(N=429)

%(N=427)

%Autonomic Nervous System Disorders

Dry Mouth

9%

5%

Sweating Increased

4%

1%

Central & Peripheral Nervous System Disorders

Headache

24%

17%

Paresthesia

2%

1%

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Nausea

18%

8%

Diarrhea

8%

6%

Constipation

5%

4%

Indigestion

3%

2%

Vomiting

3%

1%

Abdominal Pain

2%

1%

Flatulence

2%

1%

Toothache

2%

0%

General

Fatigue

8%

2%

Influenza-like Symptoms

5%

4%

Musculoskeletal System Disorder

Neck/Shoulder Pain

3%

1%

Psychiatric Disorders

Somnolence

13%

7%

Insomnia

12%

6%

Libido Decreased

7%

2%

Dreaming Abnormal

3%

2%

- Appetite Decreased

3%

1%

Lethargy

3%

1%

Respiratory System Disorders

Yawning

2%

1%

Urogenital

Ejaculation Disorder 1,2

14%

2%

Anorgasmia 3

6%

<1%

Menstrual Disorder

2%

1%

Dose Dependency of Adverse Reactions

The potential dose dependency of common adverse reactions (defined as an incidence rate of ≥5% in either the 10 mg or 20 mg Escitalopram groups) was examined on the basis of the combined incidence of adverse reactions in two fixed-dose trials. The overall incidence rates of adverse events in 10 mg Escitalopram-treated patients (66%) was similar to that of the placebo-treated patients (61%), while the incidence rate in 20 mg/day Escitalopram-treated patients was greater (86%). Table 4 shows common adverse reactions that occurred in the 20 mg/day Escitalopram group with an incidence that was approximately twice that of the 10 mg/day Escitalopram group and approximately twice that of the placebo group.

TABLE 4 Incidence of Common Adverse Reactions in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Adverse Reaction

Placebo

10 mg/day

20 mg/day

(N=311)

Escitalopram

Escitalopram

(N=310)

(N=125)

Insomnia

4%

7%

14%

Diarrhea

5%

6%

14%

Dry Mouth

3%

4%

9%

Somnolence

1%

4%

9%

Dizziness

2%

4%

7%

Sweating Increased

<1%

3%

8%

Constipation

1%

3%

6%

Fatigue

2%

2%

6%

Indigestion

1%

2%

6%

Male and Female Sexual Dysfunction with SSRIs

Although changes in sexual desire, sexual performance, and sexual satisfaction often occur as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder, they may also be a consequence of pharmacologic treatment. In particular, some evidence suggests that SSRIs can cause such untoward sexual experiences.

Reliable estimates of the incidence and severity of untoward experiences involving sexual desire, performance, and satisfaction are difficult to obtain, however, in part because patients and physicians may be reluctant to discuss them. Accordingly, estimates of the incidence of untoward sexual experience and performance cited in product labeling are likely to underestimate their actual incidence.

TABLE 5 Incidence of Sexual Side Effects in Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials Adverse Event

Escitalopram

Placebo

In Males Only

(N=407)

(N=383)

Ejaculation Disorder

(primarily ejaculatory delay)

12%

1%Libido Decreased

6%

2%

Impotence

2%

<1%

In Females Only

(N=737)

(N=636)

Libido Decreased

3%

1%

Anorgasmia

3%

<1%

There are no adequately designed studies examining sexual dysfunction with escitalopram treatment.

Priapism has been reported with all SSRIs.

While it is difficult to know the precise risk of sexual dysfunction associated with the use of SSRIs, physicians should routinely inquire about such possible side effects.

Vital Sign Changes

Escitalopram and placebo groups were compared with respect to (1) mean change from baseline in vital signs (pulse, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure) and (2) the incidence of patients meeting criteria for potentially clinically significant changes from baseline in these variables. These analyses did not reveal any clinically important changes in vital signs associated with Escitalopram treatment. In addition, a comparison of supine and standing vital sign measures in subjects receiving Escitalopram indicated that Escitalopram treatment is not associated with orthostatic changes.

Weight Changes

Patients treated with Escitalopram in controlled trials did not differ from placebo-treated patients with regard to clinically important change in body weight.

Laboratory Changes

Escitalopram and placebo groups were compared with respect to (1) mean change from baseline in various serum chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis variables, and (2) the incidence of patients meeting criteria for potentially clinically significant changes from baseline in these variables. These analyses revealed no clinically important changes in laboratory test parameters associated with Escitalopram treatment.

ECG Changes

Electrocardiograms from Escitalopram (N=625) and placebo (N=527) groups were compared with respect to outliers defined as subjects with QTc changes over 60 msec from baseline or absolute values over 500 msec post-dose, and subjects with heart rate increases to over 100 bpm or decreases to less than 50 bpm with a 25% change from baseline (tachycardic or bradycardic outliers, respectively). None of the patients in the Escitalopram group had a QTcF interval >500 msec or a prolongation >60 msec compared to 0.2% of patients in the placebo group. The incidence of tachycardic outliers was 0.2% in the Escitalopram and the placebo group. The incidence of bradycardic outliers was 0.5% in the Escitalopram group and 0.2% in the placebo group.

QTcF interval was evaluated in a randomized, placebo and active (moxifloxacin 400 mg) controlled cross-over, escalating multiple dose study in 113 healthy subjects. The maximum mean (95% upper confidence bound) difference from placebo arm were 4.5 (6.4) and 10.7 (12.7) msec for 10 mg and supratherapeutic 30 mg escitalopram given once daily, respectively. Based on the established exposure-response relationship, the predicted QTcF change from placebo arm (95% confidence interval) under the C max for the dose of 20 mg is 6.6 (7.9) msec. Escitalopram 30 mg given once daily resulted in mean C max of 1.7-fold higher than the mean C max for the maximum recommended therapeutic dose at steady state (20 mg). The exposure under supratherapeutic 30 mg dose is similar to the steady state concentrations expected in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers following a therapeutic dose of 20 mg.

Other Reactions Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Escitalopram

Following is a list of treatment-emergent adverse events, as defined in the introduction to the ADVERSE REACTIONS section, reported by the 1428 patients treated with Escitalopram for periods of up to one year in double-blind or open-label clinical trials during its premarketing evaluation. The listing does not include those events already listed in Tables 2 & 3, those events for which a drug cause was remote and at a rate less than 1% or lower than placebo, those events which were so general as to be uninformative, and those events reported only once which did not have a substantial probability of being acutely life threatening. Events are categorized by body system. Events of major clinical importance are described in the Warnings and Precautions section ( 5).

Cardiovascular - hypertension, palpitation.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Disorders - light-headed feeling, migraine.

Gastrointestinal Disorders - abdominal cramp, heartburn, gastroenteritis.

General - allergy, chest pain, fever, hot flushes, pain in limb.

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders - increased weight.

Musculoskeletal System Disorders - arthralgia, myalgia jaw stiffness.

Psychiatric Disorders - appetite increased, concentration impaired, irritability.

Reproductive Disorders/Female - menstrual cramps, menstrual disorder.

Respiratory System Disorders - bronchitis, coughing, nasal congestion, sinus congestion, sinus headache.

Skin and Appendages Disorders - rash.

Special Senses - vision blurred, tinnitus.

Urinary System Disorders - urinary frequency, urinary tract infection.

6.2 Post-Marketing Experience

Adverse Reactions Reported Subsequent to the Marketing of Escitalopram

The following additional adverse reactions have been identified from spontaneous reports of escitalopram received worldwide. These adverse reactions have been chosen for inclusion because of a combination of seriousness, frequency of reporting, or potential causal connection to escitalopram and have not been listed elsewhere in labeling. However, because these adverse reactions were reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure. These events include:

Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: anemia, agranulocytis, aplastic anemia, hemolytic anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia.

Cardiac Disorders: atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, tachycardia, torsade de pointes, ventricular arrhythmia, ventricular tachycardia.

Ear and labyrinth disorders: vertigo

Endocrine Disorders: diabetes mellitus, hyperprolactinemia, SIADH.

Eye Disorders: angle closure glaucoma, diplopia, mydriasis, visual disturbance.

Gastrointestinal Disorder: dysphagia, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gastroesophageal reflux, pancreatitis, rectal hemorrhage.

General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions: abnormal gait, asthenia, edema, fall, feeling abnormal, malaise.

Hepatobiliary Disorders: fulminant hepatitis, hepatic failure, hepatic necrosis, hepatitis.

Immune System Disorders: allergic reaction, anaphylaxis.

Investigations: bilirubin increased, decreased weight, electrocardiogram QT prolongation, hepatic enzymes increased, hypercholesterolemia, INR increased, prothrombin decreased.

Metabolism and Nutrition Disorders: hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia.

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: muscle cramp, muscle stiffness, muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis.

Nervous System Disorders: akathisia, amnesia, ataxia, choreoathetosis, cerebrovascular accident, dysarthria, dyskinesia, dystonia, extrapyramidal disorders, grand mal seizures (or convulsions), hypoaesthesia, myoclonus, nystagmus, Parkinsonism, restless legs, seizures, syncope, tardive dyskinesia, tremor.

Pregnancy, Puerperium and Perinatal Conditions: spontaneous abortion.

Psychiatric Disorders: acute psychosis, aggression, agitation, anger, anxiety, apathy, completed suicide, confusion, depersonalization, depression aggravated, delirium, delusion, disorientation, feeling unreal, hallucinations (visual and auditory), mood swings, nervousness, nightmare, panic reaction, paranoia, restlessness, self-harm or thoughts of self-harm, suicide attempt, suicidal ideation, suicidal tendency.

Renal and Urinary Disorders: acute renal failure, dysuria, urinary retention.

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: menorrhagia, priapism.

Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders: dyspnea, epistaxis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: alopecia, angioedema, dermatitis, ecchymosis, erythema multiforme, photosensitivity reaction, Stevens Johnson Syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, urticaria.

Vascular Disorders: deep vein thrombosis, flushing, hypertensive crisis, hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, phlebitis, thrombosis.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

[See Dosage and Administration ( 2.5 and 2.6), Contraindications ( 4.1) and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) ].

7.2 Serotonergic Drugs

[See Dosage and Administration ( 2.5 and 2.6), Contraindications ( 4.1) and Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) ].

7.3 Triptans

There have been rare postmarketing reports of serotonin syndrome with use of an SSRI and a triptan. If concomitant treatment of Escitalopram with a triptan is clinically warranted, careful observation of the patient is advised, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases [ see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) ].

7.4 CNS Drugs

Given the primary CNS effects of escitalopram, caution should be used when it is taken in combination with other centrally acting drugs.

7.5 Alcohol

Although Escitalopram did not potentiate the cognitive and motor effects of alcohol in a clinical trial, as with other psychotropic medications, the use of alcohol by patients taking Escitalopram is not recommended.

7.6 Drugs That Interfere With Hemostasis (NSAIDs, Aspirin, Warfarin, etc.)

Serotonin release by platelets plays an important role in hemostasis. Epidemiological studies of the case-control and cohort design that have demonstrated an association between use of psychotropic drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding have also shown that concurrent use of an NSAID or aspirin may potentiate the risk of bleeding. Altered anticoagulant effects, including increased bleeding, have been reported when SSRIs and SNRIs are coadministered with warfarin. Patients receiving warfarin therapy should be carefully monitored when Escitalopram is initiated or discontinued.

7.7 Cimetidine

In subjects who had received 21 days of 40 mg/day racemic citalopram, combined administration of 400 mg twice a day cimetidine for 8 days resulted in an increase in citalopram AUC and C max of 43% and 39%, respectively. The clinical significance of these findings is unknown.

7.8 Digoxin

In subjects who had received 21 days of 40 mg/day racemic citalopram, combined administration of citalopram and digoxin (single dose of 1 mg) did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of either citalopram or digoxin.

7.9 Lithium

Coadministration of racemic citalopram (40 mg/day for 10 days) and lithium (30 mmol/day for 5 days) had no significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of citalopram or lithium. Nevertheless, plasma lithium levels should be monitored with appropriate adjustment to the lithium dose in accordance with standard clinical practice. Because lithium may enhance the serotonergic effects of escitalopram, caution should be exercised when Escitalopram and lithium are coadministered.

7.10 Pimozide and Celexa

In a controlled study, a single dose of pimozide 2 mg co-administered with racemic citalopram 40 mg given once daily for 11 days was associated with a mean increase in QTc values of approximately 10 msec compared to pimozide given alone. Racemic citalopram did not alter the mean AUC or C max of pimozide. The mechanism of this pharmacodynamic interaction is not known.

7.11 Sumatriptan

There have been rare postmarketing reports describing patients with weakness, hyperreflexia, and incoordination following the use of an SSRI and sumatriptan. If concomitant treatment with sumatriptan and an SSRI (e.g., fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) is clinically warranted, appropriate observation of the patient is advised.

7.12 Theophylline

Combined administration of racemic citalopram (40 mg/day for 21 days) and the CYP1A2 substrate theophylline (single dose of 300 mg) did not affect the pharmacokinetics of theophylline. The effect of theophylline on the pharmacokinetics of citalopram was not evaluated.

7.13 Warfarin

Administration of 40 mg/day racemic citalopram for 21 days did not affect the pharmacokinetics of warfarin, a CYP3A4 substrate. Prothrombin time was increased by 5%, the clinical significance of which is unknown.

7.14 Carbamazepine

Combined administration of racemic citalopram (40 mg/day for 14 days) and carbamazepine (titrated to 400 mg/day for 35 days) did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine, a CYP3A4 substrate. Although trough citalopram plasma levels were unaffected, given the enzyme-inducing properties of carbamazepine, the possibility that carbamazepine might increase the clearance of escitalopram should be considered if the two drugs are coadministered.

7.15 Triazolam

Combined administration of racemic citalopram (titrated to 40 mg/day for 28 days) and the CYP3A4 substrate triazolam (single dose of 0.25 mg) did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of either citalopram or triazolam.

7.16 Ketoconazole

Combined administration of racemic citalopram (40 mg) and ketoconazole (200 mg), a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor, decreased the C max and AUC of ketoconazole by 21% and 10%, respectively, and did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of citalopram.

7.17 Ritonavir

Combined administration of a single dose of ritonavir (600 mg), both a CYP3A4 substrate and a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, and escitalopram (20 mg) did not affect the pharmacokinetics of either ritonavir or escitalopram.

7.18 CYP3A4 and -2C19 Inhibitors

In vitro studies indicated that CYP3A4 and -2C19 are the primary enzymes involved in the metabolism of escitalopram. However, coadministration of escitalopram (20 mg) and ritonavir (600 mg), a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of escitalopram. Because escitalopram is metabolized by multiple enzyme systems, inhibition of a single enzyme may not appreciably decrease escitalopram clearance.

7.19 Drugs Metabolized by Cytochrome P4502D6

In vitro studies did not reveal an inhibitory effect of escitalopram on CYP2D6. In addition, steady state levels of racemic citalopram were not significantly different in poor metabolizers and extensive CYP2D6 metabolizers after multiple-dose administration of citalopram, suggesting that coadministration, with escitalopram, of a drug that inhibits CYP2D6, is unlikely to have clinically significant effects on escitalopram metabolism. However, there are limited in vivo data suggesting a modest CYP2D6 inhibitory effect for escitalopram, i.e., coadministration of escitalopram (20 mg/day for 21 days) with the tricyclic antidepressant desipramine (single dose of 50 mg), a substrate for CYP2D6, resulted in a 40% increase in C max and a 100% increase in AUC of desipramine. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown. Nevertheless, caution is indicated in the coadministration of escitalopram and drugs metabolized by CYP2D6.

7.20 Metoprolol

Administration of 20 mg/day Escitalopram for 21 days in healthy volunteers resulted in a 50% increase in C max and 82% increase in AUC of the beta-adrenergic blocker metoprolol (given in a single dose of 100 mg). Increased metoprolol plasma levels have been associated with decreased cardioselectivity. Coadministration of Escitalopram and metoprolol had no clinically significant effects on blood pressure or heart rate.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C

In a rat embryo/fetal development study, oral administration of escitalopram (56, 112, or 150 mg/kg/day) to pregnant animals during the period of organogenesis resulted in decreased fetal body weight and associated delays in ossification at the two higher doses (approximately ≥ 56 times the maximum recommended human dose [MRHD] of 20 mg/day on a body surface area [mg/m 2] basis). Maternal toxicity (clinical signs and decreased body weight gain and food consumption), mild at 56 mg/kg/day, was present at all dose levels. The developmental no-effect dose of 56 mg/kg/day is approximately 28 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis. No teratogenicity was observed at any of the doses tested (as high as 75 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis).

When female rats were treated with escitalopram (6, 12, 24, or 48 mg/kg/day) during pregnancy and through weaning, slightly increased offspring mortality and growth retardation were noted at 48 mg/kg/day which is approximately 24 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis. Slight maternal toxicity (clinical signs and decreased body weight gain and food consumption) was seen at this dose. Slightly increased offspring mortality was also seen at 24 mg/kg/day. The no-effect dose was 12 mg/kg/day which is approximately 6 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis.

In animal reproduction studies, racemic citalopram has been shown to have adverse effects on embryo/fetal and postnatal development, including teratogenic effects, when administered at doses greater than human therapeutic doses.

In two rat embryo/fetal development studies, oral administration of racemic citalopram (32, 56, or 112 mg/kg/day) to pregnant animals during the period of organogenesis resulted in decreased embryo/fetal growth and survival and an increased incidence of fetal abnormalities (including cardiovascular and skeletal defects) at the high dose. This dose was also associated with maternal toxicity (clinical signs, decreased body weight gain). The developmental no-effect dose was 56 mg/kg/day. In a rabbit study, no adverse effects on embryo/fetal development were observed at doses of racemic citalopram of up to 16 mg/kg/day. Thus, teratogenic effects of racemic citalopram were observed at a maternally toxic dose in the rat and were not observed in the rabbit.

When female rats were treated with racemic citalopram (4.8, 12.8, or 32 mg/kg/day) from late gestation through weaning, increased offspring mortality during the first 4 days after birth and persistent offspring growth retardation were observed at the highest dose. The no-effect dose was 12.8 mg/kg/day. Similar effects on offspring mortality and growth were seen when dams were treated throughout gestation and early lactation at doses ≥ 24 mg/kg/day. A no-effect dose was not determined in that study.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women; therefore, escitalopram should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Pregnancy-Nonteratogenic Effects

Neonates exposed to Escitalopram and other SSRIs or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), late in the third trimester, have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. Such complications can arise immediately upon delivery. Reported clinical findings have included respiratory distress, cyanosis, apnea, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremor, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These features are consistent with either a direct toxic effect of SSRIs and SNRIs or, possibly, a drug discontinuation syndrome. It should be noted that, in some cases, the clinical picture is consistent with serotonin syndrome [ see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.2) ].

Infants exposed to SSRIs in pregnancy may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). PPHN occurs in 1 - 2 per 1,000 live births in the general population and is associated with substantial neonatal morbidity and mortality. Several recent epidemiologic studies suggest a positive statistical association between SSRI use (including Escitalopram) in pregnancy and PPHN. Other studies do not show a significant statistical association.

Physicians should also note the results of a prospective longitudinal study of 201 pregnant women with a history of major depression, who were either on antidepressants or had received antidepressants less than 12 weeks prior to their last menstrual period, and were in remission. Women who discontinued antidepressant medication during pregnancy showed a significant increase in relapse of their major depression compared to those women who remained on antidepressant medication throughout pregnancy.

When treating a pregnant woman with Escitalopram, the physician should carefully consider both the potential risks of taking an SSRl, along with the established benefits of treating depression with an antidepressant. This decision can only be made on a case by case basis [see Dosage and Administration [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.1) ].

8.3 Nursing Mothers

Escitalopram is excreted in human breast milk. Limited data from women taking 10-20 mg escitalopram showed that exclusively breast-fed infants receive approximately 3.9% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose of escitalopram and 1.7% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose of desmethylcitalopram. There were two reports of infants experiencing excessive somnolence, decreased feeding, and weight loss in association with breastfeeding from a racemic citalopram-treated mother; in one case, the infant was reported to recover completely upon discontinuation of racemic citalopram by its mother and, in the second case, no follow-up information was available. Caution should be exercised and breastfeeding infants should be observed for adverse reactions when Escitalopram is administered to a nursing woman.

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of Escitalopram have been established in adolescents (12 to 17 years of age) for the treatment of major depressive disorder [ see Clinical Studies ( 14.1) ]. Although maintenance efficacy in adolescent patients with major depressive disorder has not been systematically evaluated, maintenance efficacy can be extrapolated from adult data along with comparisons of escitalopram pharmacokinetic parameters in adults and adolescent patients.

The safety and effectiveness of Escitalopram have not been established in pediatric (younger than 12 years of age) patients with major depressive disorder. In a 24-week, open-label safety study in 118 children (aged 7 to 11 years) who had major depressive disorder, the safety findings were consistent with the known safety and tolerability profile for Escitalopram.

Safety and effectiveness of Escitalopram has not been established in pediatric patients less than 18 years of age with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Decreased appetite and weight loss have been observed in association with the use of SSRIs. Consequently, regular monitoring of weight and growth should be performed in children and adolescents treated with an SSRI such as Escitalopram.

8.5 Geriatric Use

Approximately 6% of the 1144 patients receiving escitalopram in controlled trials of Escitalopram in major depressive disorder and GAD were 60 years of age or older; elderly patients in these trials received daily doses of Escitalopram between 10 and 20 mg. The number of elderly patients in these trials was insufficient to adequately assess for possible differential efficacy and safety measures on the basis of age. Nevertheless, greater sensitivity of some elderly individuals to effects of Escitalopram cannot be ruled out.

SSRIs and SNRIs, including Escitalopram, have been associated with cases of clinically significant hyponatremia in elderly patients, who may be at greater risk for this adverse event [see Hyponatremia ( 5.6) ].

In two pharmacokinetic studies, escitalopram half-life was increased by approximately 50% in elderly subjects as compared to young subjects and C max was unchanged [ see Clinical Pharmacology ( 12.3) ]. 10 mg/day is the recommended dose for elderly patients [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.3) ].

Of 4422 patients in clinical studies of racemic citalopram, 1357 were 60 and over, 1034 were 65 and over, and 457 were 75 and over. No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but again, greater sensitivity of some elderly individuals cannot be ruled out.

-

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse and Dependence

Physical and Psychological Dependence

Animal studies suggest that the abuse liability of racemic citalopram is low. Escitalopram has not been systematically studied in humans for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. The premarketing clinical experience with Escitalopram did not reveal any drug-seeking behavior. However, these observations were not systematic and it is not possible to predict on the basis of this limited experience the extent to which a CNS-active drug will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, physicians should carefully evaluate Escitalopram patients for history of drug abuse and follow such patients closely, observing them for signs of misuse or abuse (e.g., development of tolerance, incrementations of dose, drug-seeking behavior).

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

In clinical trials of escitalopram, there were reports of escitalopram overdose, including overdoses of up to 600 mg, with no associated fatalities. During the postmarketing evaluation of escitalopram, Escitalopram overdoses involving overdoses of over 1000 mg have been reported. As with other SSRIs, a fatal outcome in a patient who has taken an overdose of escitalopram has been rarely reported.

Symptoms most often accompanying escitalopram overdose, alone or in combination with other drugs and/or alcohol, included convulsions, coma, dizziness, hypotension, insomnia, nausea, vomiting, sinus tachycardia, somnolence, and ECG changes (including QT prolongation and very rare cases of torsade de pointes). Acute renal failure has been very rarely reported accompanying overdose.

10.2 Management of Overdose

Establish and maintain an airway to ensure adequate ventilation and oxygenation. Gastric evacuation by lavage and use of activated charcoal should be considered. Careful observation and cardiac and vital sign monitoring are recommended, along with general symptomatic and supportive care. Due to the large volume of distribution of escitalopram, forced diuresis, dialysis, hemoperfusion, and exchange transfusion are unlikely to be of benefit. There are no specific antidotes for Escitalopram.

In managing overdosage, consider the possibility of multiple-drug involvement. The physician should consider contacting a poison control center for additional information on the treatment of any overdose.

-

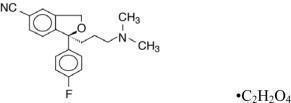

11 DESCRIPTION

Escitalopram contains escitalopram oxalate, an orally administered selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Escitalopram is the pure S-enantiomer (single isomer) of the racemic bicyclic phthalane derivative citalopram. Escitalopram oxalate is designated S-(+)-1-[3(dimethyl-amino)propyl]-1-( p-fluorophenyl)-5-phthalancarbonitrile oxalate with the following structural formula:

The molecular formula is C 20H 21FN 2O C 2H 2O 4 and the molecular weight is 414.40.

Escitalopram oxalate occurs as a fine, white to slightly-yellow powder and is freely soluble in methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), soluble in isotonic saline solution, sparingly soluble in water and ethanol, slightly soluble in ethyl acetate, and insoluble in heptane.

Escitalopram is available as tablets.

Escitalopram tablets are film-coated, round tablets containing 6.38 mg, 12.75 mg, 25.50 mg escitalopram oxalate in strengths equivalent to 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg, respectively, of escitalopram base. The 10 and 20 mg tablets are scored. The tablets also contain the follcowing inactive ingredients: colloidal silicon dioxide, corn starch, croscarmellose sodium, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, talc, and a film coating agent. The film coating agent, Opadry II White Y-22-7719, contains the following ingredients: hypromellose; polydextrose; polyethylene glycol; triacetin; and titanium dioxide.

Meets USP Dissolution Test 2.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of antidepressant action of escitalopram, the S-enantiomer of racemic citalopram, is presumed to be linked to potentiation of serotonergic activity in the central nervous system (CNS) resulting from its inhibition of CNS neuronal reuptake of serotonin (5-HT).

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

In vitro and in vivo studies in animals suggest that escitalopram is a highly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with minimal effects on norepinephrine and dopamine neuronal reuptake. Escitalopram is at least 100-fold more potent than the R-enantiomer with respect to inhibition of 5-HT reuptake and inhibition of 5-HT neuronal firing rate. Tolerance to a model of antidepressant effect in rats was not induced by long-term (up to 5 weeks) treatment with escitalopram. Escitalopram has no or very low affinity for serotonergic (5-HT 1-7) or other receptors including alpha- and beta-adrenergic, dopamine (D 1-5), histamine (H 1-3), muscarinic (M 1-5), and benzodiazepine receptors. Escitalopram also does not bind to, or has low affinity for, various ion channels including Na +, K +, Cl -, and Ca ++ channels. Antagonism of muscarinic, histaminergic, and adrenergic receptors has been hypothesized to be associated with various anticholinergic, sedative, and cardiovascular side effects of other psychotropic drugs.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of escitalopram are linear and dose-proportional in a dose range of 10 to 30 mg/day. Biotransformation of escitalopram is mainly hepatic, with a mean terminal half-life of about 27-32 hours. With once-daily dosing, steady state plasma concentrations are achieved within approximately one week. At steady state, the extent of accumulation of escitalopram in plasma in young healthy subjects was 2.2-2.5 times the plasma concentrations observed after a single dose. The tablet and the oral solution dosage forms of escitalopram oxalate are bioequivalent.

Absorption and Distribution

Following a single oral dose (20 mg tablet or solution) of escitalopram, peak blood levels occur at about 5 hours. Absorption of escitalopram is not affected by food.

The absolute bioavailability of citalopram is about 80% relative to an intravenous dose, and the volume of distribution of citalopram is about 12 L/kg. Data specific on escitalopram are unavailable.

The binding of escitalopram to human plasma proteins is approximately 56%.

Metabolism and Elimination

Following oral administrations of escitalopram, the fraction of drug recovered in the urine as escitalopram and S-demethylcitalopram (S-DCT) is about 8% and 10%, respectively. The oral clearance of escitalopram is 600 mL/min, with approximately 7% of that due to renal clearance.

Escitalopram is metabolized to S-DCT and S-didemethylcitalopram (S-DDCT). In humans, unchanged escitalopram is the predominant compound in plasma. At steady state, the concentration of the escitalopram metabolite S-DCT in plasma is approximately one-third that of escitalopram. The level of S-DDCT was not detectable in most subjects. In vitro studies show that escitalopram is at least 7 and 27 times more potent than S-DCT and S-DDCT, respectively, in the inhibition of serotonin reuptake, suggesting that the metabolites of escitalopram do not contribute significantly to the antidepressant actions of escitalopram. S-DCT and S-DDCT also have no or very low affinity for serotonergic (5-HT 1-7) or other receptors including alpha- and beta-adrenergic, dopamine (D 1-5), histamine (H 1-3), muscarinic (M 1-5), and benzodiazepine receptors. S-DCT and S-DDCT also do not bind to various ion channels including Na +, K +, Cl -, and Ca ++ channels.

In vitro studies using human liver microsomes indicated that CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 are the primary isozymes involved in the Ndemethylation of escitalopram.

Population Subgroups

Age

Adolescents - In a single dose study of 10 mg escitalopram, AUC of escitalopram decreased by 19%, and C max increased by 26% in healthy adolescent subjects (12 to 17 years of age) compared to adults. Following multiple dosing of 40 mg/day citalopram, escitalopram elimination half-life, steady-state C max and AUC were similar in patients with MDD (12 to 17 years of age) compared to adult patients. No adjustment of dosage is needed in adolescent patients.

Elderly - Escitalopram pharmacokinetics in subjects ≥ 65 years of age were compared to younger subjects in a single-dose and a multiple-dose study. Escitalopram AUC and half-life were increased by approximately 50% in elderly subjects, and C max was unchanged. 10 mg is the recommended dose for elderly patients [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.3) ].

Gender - Based on data from single- and multiple-dose studies measuring escitalopram in elderly, young adults, and adolescents, no dosage adjustment on the basis of gender is needed.

Reduced hepatic function - Citalopram oral clearance was reduced by 37% and half-life was doubled in patients with reduced hepatic function compared to normal subjects. 10 mg is the recommended dose of escitalopram for most hepatically impaired patients [ see Dosage and Administration ( 2.3) ].

Reduced renal function - In patients with mild to moderate renal function impairment, oral clearance of citalopram was reduced by 17% compared to normal subjects. No adjustment of dosage for such patients is recommended. No information is available about the pharmacokinetics of escitalopram in patients with severely reduced renal function (creatinine clearance < 20 mL/min).

Drug-Drug Interactions

In vitro enzyme inhibition data did not reveal an inhibitory effect of escitalopram on CYP3A4, -1A2, -2C9, -2C19, and -2E1. Based on in vitro data, escitalopram would be expected to have little inhibitory effect on in vivo metabolism mediated by these cytochromes. While in vivo data to address this question are limited, results from drug interaction studies suggest that escitalopram, at a dose of 20 mg, has no 3A4 inhibitory effect and a modest 2D6 inhibitory effect. See Drug Interactions ( 7.18) for more detailed information on available drug interaction data.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Racemic citalopram was administered in the diet to NMRI/BOM strain mice and COBS WI strain rats for 18 and 24 months, respectively. There was no evidence for carcinogenicity of racemic citalopram in mice receiving up to 240 mg/kg/day. There was an increased incidence of small intestine carcinoma in rats receiving 8 or 24 mg/kg/day racemic citalopram. A no-effect dose for this finding was not established. The relevance of these findings to humans is unknown.

Mutagenesis

Racemic citalopram was mutagenic in the in vitro bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test) in 2 of 5 bacterial strains (Salmonella TA98 and TA1537) in the absence of metabolic activation. It was clastogenic in the in vitro Chinese hamster lung cell assay for chromosomal aberrations in the presence and absence of metabolic activation. Racemic citalopram was not mutagenic in the in vitro mammalian forward gene mutation assay (HPRT) in mouse lymphoma cells or in a coupled in vitro/in vivo unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) assay in rat liver. It was not clastogenic in the in vitro chromosomal aberration assay in human lymphocytes or in two in vivo mouse micronucleus assays.

Impairment of Fertility

When racemic citalopram was administered orally to 16 male and 24 female rats prior to and throughout mating and gestation at doses of 32, 48, and 72 mg/kg/day, mating was decreased at all doses, and fertility was decreased at doses ≥ 32 mg/kg/day. Gestation duration was increased at 48 mg/kg/day.

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

Retinal Changes in Rats

Pathologic changes (degeneration/atrophy) were observed in the retinas of albino rats in the 2-year carcinogenicity study with racemic citalopram. There was an increase in both incidence and severity of retinal pathology in both male and female rats receiving 80 mg/kg/day. Similar findings were not present in rats receiving 24 mg/kg/day of racemic citalopram for two years, in mice receiving up to 240 mg/kg/day of racemic citalopram for 18 months, or in dogs receiving up to 20 mg/kg/day of racemic citalopram for one year.

Additional studies to investigate the mechanism for this pathology have not been performed, and the potential significance of this effect in humans has not been established.

Cardiovascular Changes in Dogs

In a one-year toxicology study, 5 of 10 beagle dogs receiving oral racemic citalopram doses of 8 mg/kg/day died suddenly between weeks 17 and 31 following initiation of treatment. Sudden deaths were not observed in rats at doses of racemic citalopram up to 120 mg/kg/day, which produced plasma levels of citalopram and its metabolites demethylcitalopram and didemethylcitalopram (DDCT) similar to those observed in dogs at 8 mg/kg/day. A subsequent intravenous dosing study demonstrated that in beagle dogs, racemic DDCT caused QT prolongation, a known risk factor for the observed outcome in dogs.

-

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Major Depressive Disorder

Adolescents

The efficacy of Escitalopram as an acute treatment for major depressive disorder in adolescent patients was established in an 8-week, flexible-dose, placebo-controlled study that compared Escitalopram 10-20 mg/day to placebo in outpatients 12 to 17 years of age inclusive who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder. The primary outcome was change from baseline to endpoint in the Children’s Depression Rating Scale - Revised (CDRS-R). In this study, Escitalopram showed statistically significant greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the CDRS-R.

The efficacy of Escitalopram in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents was established, in part, on the basis of extrapolation from the 8-week, flexible-dose, placebo-controlled study with racemic citalopram 20-40 mg/day. In this outpatient study in children and adolescents 7 to 17 years of age who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, citalopram treatment showed statistically significant greater mean improvement from baseline, compared to placebo, on the CDRS-R; the positive results for this trial largely came from the adolescent subgroup.

Two additional flexible-dose, placebo-controlled MDD studies (one Escitalopram study in patients ages 7 to 17 and one citalopram study in adolescents) did not demonstrate efficacy.

Although maintenance efficacy in adolescent patients has not been systematically evaluated, maintenance efficacy can be extrapolated from adult data along with comparisons of escitalopram pharmacokinetic parameters in adults and adolescent patients.

Adults

The efficacy of Escitalopram as a treatment for major depressive disorder was established in three, 8-week, placebo-controlled studies conducted in outpatients between 18 and 65 years of age who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder. The primary outcome in all three studies was change from baseline to endpoint in the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

A fixed-dose study compared 10 mg/day Escitalopram and 20 mg/day Escitalopram to placebo and 40 mg/day citalopram. The 10 mg/day and 20 mg/day Escitalopram treatment groups showed statistically significant greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the MADRS. The 10 mg and 20 mg Escitalopram groups were similar on this outcome measure.

In a second fixed-dose study of 10 mg/day Escitalopram and placebo, the 10 mg/day Escitalopram treatment group showed statistically significant greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the MADRS.

In a flexible-dose study, comparing Escitalopram, titrated between 10 and 20 mg/day, to placebo and citalopram, titrated between 20 and 40 mg/day, the Escitalopram treatment group showed statistically significant greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the MADRS.

Analyses of the relationship between treatment outcome and age, gender, and race did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of these patient characteristics.

In a longer-term trial, 274 patients meeting (DSM-IV) criteria for major depressive disorder, who had responded during an initial 8-week, open-label treatment phase with Escitalopram 10 or 20 mg/day, were randomized to continuation of Escitalopram at their same dose, or to placebo, for up to 36 weeks of observation for relapse. Response during the open-label phase was defined by having a decrease of the MADRS total score to ≤ 12. Relapse during the double-blind phase was defined as an increase of the MADRS total score to ≥ 22, or discontinuation due to insufficient clinical response. Patients receiving continued Escitalopram experienced a statistically significant longer time to relapse compared to those receiving placebo.

14.2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

The efficacy of Escitalopram in the acute treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) was demonstrated in three, 8-week, multicenter, flexible-dose, placebo-controlled studies that compared Escitalopram 10-20 mg/day to placebo in adult outpatients between 18 and 80 years of age who met DSM-IV criteria for GAD. In all three studies, Escitalopram showed statistically significant greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A).

There were too few patients in differing ethnic and age groups to adequately assess whether or not Escitalopram has differential effects in these groups. There was no difference in response to Escitalopram between men and women.

-

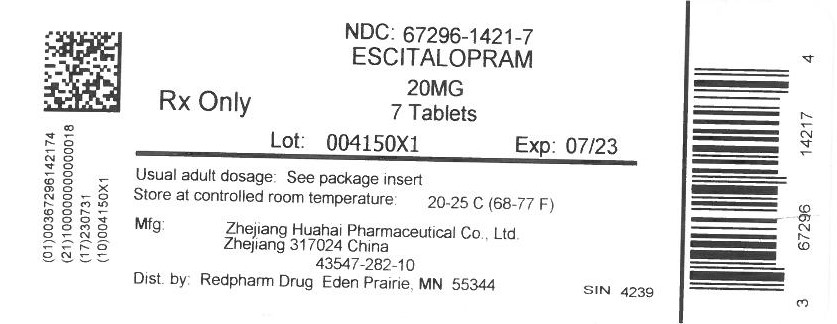

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

16.1 Tablets:

Escitalopram Tablets, USP, 5 mg are round, white to off-white, biconvex, film coated tablets, debossed with "P 5" on one side and plain on the other side. They are supplied in bottles of 100 tablets (NDC: 43547-280-10) and bottles of 1,000 tablets (NDC: 43547-280-11).

Escitalopram Tablets, USP, 10 mg are round, white to off-white, biconvex, film coated tablets, debossed with "P 10" on the scored side and plain on the other side. They are supplied in bottles of 100 tablets (NDC: 43547-281-10) and bottles of 1,000 tablets (NDC: 43547-281-11).