CHENODIOL tablet, film coated

Chenodiol by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Chenodiol by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Nexgen Pharma, Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

SPECIAL NOTE

Because of the potential hepatotoxicity of Chenodiol, the poor response rate in some subgroups of Chenodiol treated patients, and an increased rate of a need for cholecystectomy in other Chenodiol treated subgroups, Chenodiol is not an appropriate treatment for many patients with gallstones. Chenodiol should be reserved for carefully selected patients and treatment must be accompanied by systematic monitoring for liver function alterations. Aspects of patient selection, response rates and risks versus benefits are given in the insert.

-

DESCRIPTION

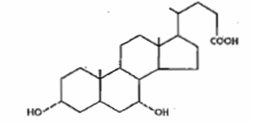

Chenodiol is the non-proprietary name for chenodeoxycholic acid, a naturally occurring human bile acid. It is a bitter-tasting white powder consisting of crystalline and amorphous particles freely soluble in methanol, acetone and acetic acid and practically insoluble in water. Its chemical name is 3α, 7α-dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid (C24H40O4), it has a molecular weight of 392.58, and its structure is shown as:

Chenodiol film-coated tablets for oral administration contain 250 mg of Chenodiol.

Inactive ingredients: pregelatinized starch; silicon dioxide; microcrystalline cellulose, sodium starch glycollate; and magnesium stearate; the thin-film coating contains: opadry YS-2-7035 [consisting of methylcellulose and glycerin] and sodium lauryl sulfate.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

At therapeutic doses, Chenodiol suppresses hepatic synthesis of both cholesterol and cholic acid, gradually replacing the latter and its metabolite, deoxycholic acid, in an expanded bile acid pool. These actions contribute to biliary cholesterol desaturation and gradual dissolution of radiolucent cholesterol gallstones in the presence of a gall-bladder visualized by oral cholecystography. Chenodiol has no effect on radiopaque (calcified) gallstones or on radiolucent bile pigment stones.

Chenodiol is well absorbed from the small intestine and taken up by the liver where it is converted to its taurine and glycine conjugates and secreted in bile. Owing to 60 % to 80% first-pass hepatic clearance, the body pool of Chenodiol resides mainly in the enterohepatic circulation; serum and urinary bile acid levels are not significantly affected during Chenodiol therapy.

At steady-state, an amount of Chenodiol near the daily dose escapes to the colon and is converted by bacterial action to lithocholic acid. About 80% of the lithocholate is excreted in the feces; the remainder is absorbed and converted in the liver to its poorly absorbed sulfolithocholyl conjugates. During Chenodiol therapy there is only a minor increase in biliary lithocholate, while fecal bile acids are increased three- to four-fold.

Chenodiol is unequivocally hepatotoxic in many animal species, including sub-human primates at doses close to the human dose. Although the theoretical cause is the metabolite, lithocholic acid, an established hepatotoxin, and man has an efficient mechanism for sulfating and eliminating this substance, there is some evidence that the demonstrated hepatotoxicity is partly due to Chenodiol per se. The hepatotoxicity of lithocholic acid is characterized biochemically and morphologically as cholestatic.

Man has the capacity to form sulfate conjugates of lithocholic acid. Variation in this capacity among individuals has not been well established and a recent published report suggests that patients who develop Chenodiol-induced serum aminotransferase elevations are poor sulfators of lithocholic acid (see ADVERSE REACTIONS and WARNINGS).

General Clinical Results: Both the desaturation of bile and the clinical dissolution of cholesterol gallstones are dose-related. In the National Cooperative Gallstone Study (NCGS) involving 305 patients in each treatment group, placebo and Chenodiol dosages of 375 mg and 750 mg per day were associated with complete stone dissolution in 0.8%, 5.2% and 13.5%, respectively, of enrolled subjects over 24 months of treatment. Uncontrolled clinical trials using higher doses than those used in the NCGS have shown complete dissolution rates of 28% to 38% of enrolled patients receiving body weight doses of from 13 to 16 mg/kg/day for up to 24 months. In a prospective trial using 15 mg/kg/day, 31% enrolled surgical-risk patients treated more than six months (n = 86) achieved complete confirmed dissolutions.

Observed stone dissolution rates achieved with Chenodiol treatment are higher in subgroups having certain pretreatment characteristics. In the NCGS, patients with small (less than 15 mm in diameter) radiolucent stones, the observed rate of complete dissolution was approximately 20% on 750 mg/day. In the uncontrolled trails using 13 to 16 mg/kg/day doses of Chenodiol, the rates of complete dissolution for small radiolucent stones ranged from 42% to 60%. Even higher dissolution rates have been observed in patients with small floatable stones. (See Floatable versus Nonfloatable Stones below). Some obese patients and occasional normal weight patients fail to achieve bile desaturation even with doses of Chenodiol up to 19 mg/kg/day for unknown reasons. Although dissolution is generally higher with increased dosage of Chenodiol, doses that are too low are associated with increased cholecystectomy rates (see ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Stones have recurred within five years in about 50% of patients following complete confirmed dissolutions. Although retreatment with Chenodiol has proven successful in dissolving some newly formed stones, the indications for, and safety of, retreatment are not well defined. Serum aminotransferase elevations and diarrhea have been notable in all clinical trials and are dose-related (refer to ADVERSE REACTIONS and WARNINGSsections for full information).

Floatable versus Nonfloatable Stones: A major finding in clinical trials was a difference between floatable and nonfloatable stones, with respect to both natural history and response to Chenodiol. Over the two-year course of the National Cooperative Gallstone Study (NCGS), placebo-treated patients with floatable stones (n = 47) had significantly higher rates of biliary pain and cholecystectomy than patients with nonfloatable stones (n = 258) (47% versus 27% and 19%versus 4%, respectively). Chenodiol treatment (750 mg/day) compared to placebo was associated with a significant reduction in both biliary pain and the cholecystectomy rates in the group with floatable stones (27% versus 47% and 1.5% versus 19%, respectively). In an uncontrolled clinical trial using 15 mg/kg/day, 70% of the patients with small (less than 15 mm) floatable stones (n = 10) had complete confirmed dissolution.

In the NCGS in patients with nonfloatable stones, Chenodiol produced no reduction in biliary pain and showed a tendency to increase the cholecystectomy rate (8% versus 4%). This finding was more pronounced with doses of Chenodiol below 10 mg/kg. The subgroup of patients with nonfloatable stones and a history of biliary pain had the highest rates of cholecystectomy and aminotransferase elevations during Chenodiol treatment. Except for the NCGS subgroup with pretreatment biliary pain, dose-related aminotransferase elevations and diarrhea have occurred with equal frequency in patients with floatable or nonfloatable stones. In the uncontrolled clinical trial mentioned above, 27% of the patients with nonfloatable stones (n = 59) had complete confirmed dissolutions, including 35% with small (less than 15 mm) (n= 40) and only 11% with large, nonfloatable stones (n= 19).

Of 916 patients enrolled NCGS, 17.6% had stones seen in upright form (horizontal X-ray beam) to float in the dye-laden bile during oral cholecystography using iopanoic acid. Other investigators report similar findings. Floatable stones are not detected by ultrasonography in the absence of dye. Chemical analysis has shown floatable stones to be essentially pure cholesterol.

Other Radiographic and Laboratory Features: Radiolucent stones may have rims or centers of opacity representing calcification. Pigment stones and partially calcified radiolucent stones do not respond to Chenodiol. Subtle calcification can sometimes be detected in flat film X-rays, if not obvious in the oral cholecystogram. Among nonfloatable stones, cholesterol stones are more apt than pigment stones to be smooth surfaced, less than 0.5 cm in diameter, and to occur in numbers less than 10. As stone size number and volume increase, the probability of dissolution within 24 months decreases. Hemolytic disorders, chronic alcoholism, biliary cirrhosis and bacterial invasion of the biliary system predispose to pigment gallstone formation. Pigment stones of primary biliary cirrhosis should be suspected in patients with elevated alkaline phosphates, especially if positive anti-mitochondrial antibodies are present. The presence of microscopic cholesterol crystals in aspirated gallbladder bile, and demonstration of cholesterol super saturation by bile lipid analysis increase the likelihood that the stones are cholesterol stones.

PATIENT SELECTION

Evaluation of Surgical Risk: Surgery offers the advantage of immediate and permanent stone removal but carries a fairly high risk in some patients. About 5% of cholecystectomized patients have residual symptoms or retained common duct stones. The spectrum to surgical risk varies as a function of age and the presence of disease other than cholelithiasis. Selected tabulation of results from the National Halothane Study (JAMA, 1968, 197:775-778) is shown below: the study included 27,600 cholecystectomies.

- Mortality per Operation (Smoothed rates with denominators adjusted to one death)

Mortality per Operation (Smoothed rates with denominators adjusted to one death) * Includes those with good health or moderate systemic disease, with or without emergency surgery. ** Severe or extreme systemic disease, with or with-out emergency surgery. Low Risk Patients*

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy & Common Duct Exploration

Women

0-49 yrs.

1/1851

1/469

50-69 yrs.

1/357

1/99

Men

0-49 yrs.

1/981

1/243

50-69 yrs.

1/185

1/52

High Risk Patients**

Women

0-49 yrs.

1/79

1/21

50-69 yrs.

1/56

1/17

Men

0-49 yrs.

1/41

1/11

50-69 yrs.

1/30

1/9

Women in good health, or having only moderate systemic disease, under 49 years of age have the lowest rate (0.054%); men in all categories have a surgical mortality rate twice that of women; common duct exploration quadruples the rates in all categories; the rates rise with each decade of life and increase tenfold or more in all categories with severe or extreme systemic disease.

Relatively young patients requiring treatment might be better treated by surgery than with Chenodiol, because treatment with Chenodiol, even if successful, is associated with a high rate of recurrence. The long-term consequences of repeated courses of Chenodiol in terms of liver toxicity, neoplasia and elevated cholesterol levels are not known.

Watchful waiting has the advantage that no therapy may ever be required. For patients with silent or minimally symptomatic stones, the rate of moderate to severe symptoms or gallstone complications is estimated to be between 2% and 6% per year, leading to a cumulative rate of 7% and 27% in five years. Presumably the rate is higher for patients already having symptoms.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Chenodiol is indicated for patients with radiolucent stones in well-opacifying gallbladders, in whom selective surgery would be undertaken except for the presence of increased surgical risk due to systemic disease or age. The likelihood of successful dissolution is far greater if the stones are floatable or small. For patients with nonfloatable stones, dissolution is less likely and added weight should be given to the risk that more emergent surgery might result from a delay due to unsuccessful treatment. Safety of use beyond 24 months is not established. Chenodiol will not dissolve calcified (radiopaque) or radiolucent bile pigment stones.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Chenodiol is contraindicated in the presence of known hepatocyte dysfunction or bile ductal abnormalities such as intrahepatic cholestasis, primary biliary cirrhosis or sclerosing cholangitis (see WARNINGS); a gallbladder confirmed as non-visualizing after two consecutive single doses of dye; radiopaque stones; or gallstone complications or compelling reasons for gallbladder surgery including unremitting acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, biliary obstruction, gallstone pancreatitis, or biliary gastrointestinal fistula.

Pregnancy Category X:

Chenodiol may cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Serious hepatic, renal and adrenal lesions occurred in fetuses of female Rhesus monkeys given 60 to 90 mg/kg/day (4 to 6 times the maximum recommended human dose, MRHD) from day 21 to day 45 of pregnancy. Hepatic lesions also occurred in neonatal baboons whose mothers had received 18 to 38 mg/kg (1 to 2 times the MRHD), all during pregnancy. Fetal malformations were not observed. Neither fetal liver damage nor fetal abnormalities occurred in reproduction studies in rats and hamsters. No human data are available at this time. Chenodiol is contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.

-

WARNINGS

Safe use of Chenodiol depends upon selection of patients without pre-existing liver disease and upon faithful monitoring of serum aminotransferase levels to detect drug-induced liver toxicity. Aminotransferase elevations over three times the upper limit of normal have required discontinuation of Chenodiol in 2% to 3% of patients. Although clinical and biopsy studies have not shown fulminant lesions, the possibility remains that an occasional patient may develop serious hepatic disease. Three patients with biochemical and histologic pictures of chronic active hepatitis while on Chenodiol, 375 mg/day or 750 mg/day, have been reported. The biochemical abnormalities returned spontaneously to normal in two of the patients within 13 and 17 months; and after 17 months’ treatment with prednisone in the third. Follow-up biopsies were not done; and the causal relationship of the drug could not be determined. Another biopsied patient was terminated from therapy because of elevated aminotransferase levels and a liver biopsy was interpreted as showing active drug hepatitis.

One patient with sclerosing cholangitis, biliary cirrhosis and history of jaundice died during Chenodiol treatment for hepatic duct stones. Before treatment, serum aminotransferase and alkaline phosphate levels were over twice the upper limit of normal; within one month they rose to over 10 times normal. Chenodiol was discontinued at seven weeks, when the patient was hospitalized with advanced hepatic failure and E. coli peritonitis; death ensued at the eighth week. A contribution of Chenodiol to the fatal outcome could not be ruled out.

Epidemiologic studies suggest that bile acids might contribute to human colon cancer, but direct evidence is lacking. Bile acids, including Chenodiol and lithocholic acid, have no carcinogenic potential in animal models, but have been shown to increase the number of tumors when administered with certain known carcinogens. The possibility that Chenodiol therapy might contribute to colon cancer in otherwise susceptible individuals cannot be ruled out.

-

PRECAUTIONS

Information for patients

Patients should be counseled on the importance of periodic visits for liver function tests and oral cholecystograms (or ultrasonograms) for monitoring stone dissolution; they should be made aware of the symptoms of gallstone complications and be warned to report immediately such symptoms to the physician. Patients should be instructed on ways to facilitate faithful compliance with the dosage regimen throughout the usual long term of therapy, and on temporary dose reduction if episodes of diarrhea occur.

Drug interactions

Bile acid sequestering agents, such as cholestyramine and colestipol, may interfere with the action of Chenodiol by reducing its absorption. Aluminum-based antacids have been shown to absorb bile acids in vitro and may be expected to interfere with Chenodiol in the same manner as the sequestering agents. Estrogen, oral contraceptive and collaborate (and perhaps other lipid-lowering drugs) increase biliary cholesterol secretion, and the incidence of cholesterol gallstones, hence, may counteract the effectiveness of Chenodiol.

Due to its hepatotoxicity, Chenodiol can affect the pharmacodynamics of coumarin and its derivatives, causing unexpected prolongation of the prothrombin time and hemorrhages. Patients on concomitant therapy with Chenodiol and coumarin or its derivatives should be monitored carefully. If prolongation of prothrombin time is observed, the coumarin dosage should be readjusted to give a prothrombin time 1½ to 2 times normal. If necessary Chenodiol should be discontinued.

Carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, impairment of fertility

A two-year oral study of Chenodiol in rats failed to show a carcinogenic potential at the tested levels of 15 to 60 mg/kg/day (1 to 4 times the maximum recommended human dose, MRHD). It has been reported that Chenodiol given in long-term studies at oral doses up to 600 mg/kg/day (40 times the MRHD) to rats and 1000 mg/kg/day (65 times the MRHD) to mice induced benign and malignant liver cell tumors in female rats and cholangiomata in female rats and male mice. Two-year studies of lithocholic acid (a major metabolite of Chenodiol) in mice (125 to 250 mg/kg/day) and rats (250 and 500 mg/kg/day) found it not to be carcinogenic. The dietary administration of Lithocholic acid to chickens is reported to cause hepatic adenomatous hyperplasia.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Hepatobiliary: Dose-related serum aminotransferase (mainly SGPT) elevations, usually not accompanied by rises in alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin, occurred in 30% or more of patients treated with the recommended dose of Chenodiol. In most cases, these elevations were minor (1½ to 3 times the upper limit of laboratory normal) and transient, returning to within the normal range within six months despite continued administration of the drug. In 2% to 3% of patients, SGPT levels rose to over three times the upper limit of laboratory normal, recurred on re-challenge with the drug, and required discontinuation of Chenodiol treatment. Enzyme levels have returned to normal following withdrawal of Chenodiol (see WARNINGS).

Morphologic studies of liver biopsies taken before and after 9 and 24 months of treatment with Chenodiol have shown that 63% of the patients prior to Chenodiol treatment had evidence of intrahepatic cholestasis. Almost all pretreatment patients had electron microscopic abnormalities. By the ninth month of treatment, reexamination of two-thirds of the patients showed an 89% incidence of the signs of intrahepatic cholestasis. Two of 89 patients at the ninth month had lithocholate-like lesions in the canalicular membrane, although there were not clinical enzyme abnormalities in the face of continued treatment and no change in Type 2 light microscopic parameters.

Increased Cholecystectomy Rate: NCGS patients with a history of biliary pain prior to treatment had higher cholecystectomy rates during the study if assigned to low dosage Chenodiol (375 mg/day) than if assigned to either placebo or high dosage Chenodiol (750 mg/day). The association with low dosage Chenodiol though not clearly a causal one, suggests that patients unable to take higher doses of Chenodiol may be at greater risk of cholecystectomy.

Gastrointestinal: Dose-related diarrhea has been encountered in 30% to 40% of Chenodiol-treated patients and may occur at any time during treatment but is most commonly encountered when treatment is initiated. Usually, the diarrhea is mild, translucent, well-tolerated and does not interfere with therapy. Dose reduction has been required in 10% to 15% of patients, and in a controlled trial about half of these required a permanent reduction in dose. Anti-diarrhea agents have proven useful in some patients.

Discontinuation of Chenodiol because of failure to control diarrhea is to be expected in approximately 3% of patients treated. Steady epigastric pain with nausea typical of lithiasis (biliary colic) usually is easily distinguishable from the crampy abdominal pain of drug-induced diarrhea.

Other less frequent, gastrointestinal side effects reported include urgency, cramps, heartburn, constipation, nausea, and vomiting, anorexic, epigastric distress, dyspepsia, flatulence and nonspecific abdominal pain.

Serum Lipids: Serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol may rise 10% or more during administration of Chenodiol: no change has been seen in the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) fraction; small decreases in serum triglyceride levels for females have been reported.

Hematologic: Decreases in white cell count, never below 3000, have been noted in a few patients treated with Chenodiol; the drug was continued in all patients without incident.

- DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The recommended dose range for Chenodiol is 13 to 16 mg/kg/day in two divided doses, morning and night, starting with 250 mg b.i.d. the first two weeks and increasing by 250 mg/day each week thereafter until the recommended or maximum tolerated dose is reached. If diarrhea occurs during dosage buildup or later in treatment, it usually can be controlled by temporary dosage adjustment until symptoms abate, after which the previous dosage usually is tolerated. Dosage less than 10 mg/kg usually is ineffective and may be associated with increased risk of cholecystectomy, so is not recommended.

Weight/Dosage Guide Body Weight

Recommended Tablets

per Day

Dose Range

(mg/kg)

- Lbs.

- Kgs.

- 100-130

- 45-58

3

- 17-13

- 131-185

- 59-75

4

- 17-13

- 186-200

- 76-90

5

- 18-14

- 201-235

- 91-107

6

- 18-14

- 236-275

- 108-125

7

- 18-14

The optimal frequency of monitoring liver function tests is not known. It is suggested that serum aminotransferase levels should be monitored monthly for the first three months and every three months thereafter during Chenodiol administration. Under NCGS guidelines, if a minor, usually transient elevation (1½ to3 three times the upper limit of normal) persisted longer than three to six months, Chenodiol was discontinued and resumed only after the aminotransferase level returned to normal; however, allowing the elevation to persist over such an interval is not known to be safe. Elevations over three times the upper limit of normal require immediate discontinuation of Chenodiol and usually reoccur on challenge.

Serum cholesterol should be monitored at six-month intervals. It may be advisable to discontinue Chenodiol if cholesterol rises above the acceptable age-adjusted limit for given patient.

Oral cholecystograms or ultrasonograms are recommended at six- to nine-month intervals to monitor response. Complete dissolutions should be confirmed by a repeat test after one to three months continued Chenodiol administration. Most patients who eventually achieve complete dissolution will show partial (or complete) dissolution at the first on-treatment test. If partial dissolution is not seen by nine to 12 months, the likelihood of success of treating longer is greatly reduced; Chenodiol should be discontinued if there is no response by 18 months. Safety of use beyond 24 months is not established.

Stone recurrence can be expected within five years in 50% of cases. After confirmed dissolution, treatment generally should be stopped. Serial cholecystograms or ultrasonograms are recommended to monitor for recurrence, keeping in mind that radiolucency and gallbladder function should be established before starting another course of Chenodiol. A prophylactic dose is not established; reduced doses cannot be recommended; stones have recurred on 500 mg/day. Low cholesterol or carbohydrate diets, and dietary bran, have been reported to reduce biliary cholesterol; maintenance of reduced weight is recommended to forestall stone recurrence.

-

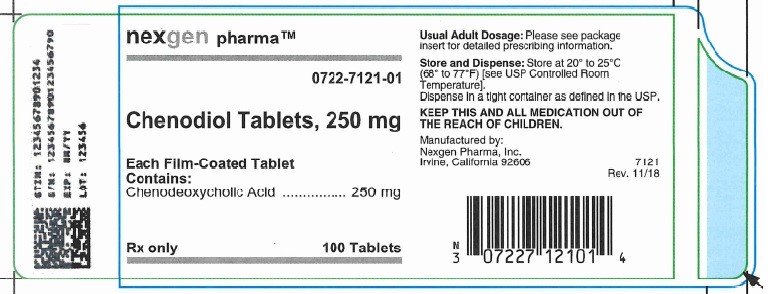

HOW SUPPLIED

Chenodiol is available as white film-coated 250 mg tablets imprinted “MP” on one side and "250" on the other side and are offered in bottles of 100 tablets (NDC: 0722-7121-01).

Store at 20oC to 25oC (68oF to 77oF) [see USP Controlled Room Temperature].

Dispense in a tight container.

Manufactured by: Nexgen Pharma, Inc., Irvine, CA 92606, USA

Rev. 09/2019

- LABEL PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

CHENODIOL

chenodiol tablet, film coatedProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0722-7121 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength CHENODIOL (UNII: 0GEI24LG0J) (CHENODIOL - UNII:0GEI24LG0J) CHENODIOL 250 mg Product Characteristics Color WHITE (White to Off-White) Score no score Shape ROUND Size 10mm Flavor Imprint Code MP;250 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0722-7121-01 1 in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 10/22/2009 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA091019 10/22/2009 Labeler - Nexgen Pharma, Inc. (048488621)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.