TIAGABINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet

tiagabine hydrochloride by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

tiagabine hydrochloride by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Wilshire Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Centaur Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

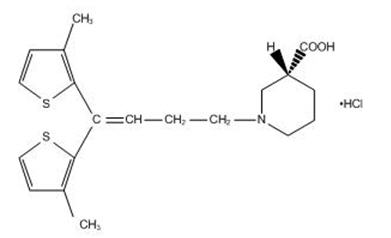

DESCRIPTION

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets are an antiepilepsy drug available as 2 mg, 4 mg, 12 mg, and 16 mg tablets for oral administration. Its chemical name is (-)-(R)-1-[4,4-Bis(3-methyl-2-thienyl)-3-butenyl]nipecotic acid hydrochloride, its molecular formula is C20H25NO2S2 HCl, and its molecular weight is 412.0. Tiagabine hydrochloride is a white to off-white, odorless, crystalline powder. It is insoluble in heptane, sparingly soluble in water, and soluble in aqueous base. The structural formula is:

Inactive Ingredients

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets contain the following inactive ingredients: Anhydrous lactose, microcrystalline cellulose, pregelatinized starch, crospovidone, polyethylene glycol 6000, butylated hydroxyanisole, propyl gallate, colloidal silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, stearic acid, hydroxypropyl cellulose, hypromellose and titanium dioxide.

In addition, individual tablets contain:

- 2 mg tablets: FD&C Yellow No. 6.

- 4 mg tablets: D&C Yellow No. 10.

- 12 mg tablets: D&C Yellow No. 10 and FD&C Blue No. 1.

- 16 mg tablets: FD&C Blue No. 2.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanism by which tiagabine exerts its antiseizure effect is unknown, although it is believed to be related to its ability, documented in in vitro experiments, to enhance the activity of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. These experiments have shown that tiagabine binds to recognition sites associated with the GABA uptake carrier. It is thought that, by this action, tiagabine blocks GABA uptake into presynaptic neurons, permitting more GABA to be available for receptor binding on the surfaces of post-synaptic cells. Inhibition of GABA uptake has been shown for synaptosomes, neuronal cell cultures, and glial cell cultures. In rat-derived hippocampal slices, tiagabine has been shown to prolong GABA-mediated inhibitory post-synaptic potentials. Tiagabine increases the amount of GABA available in the extracellular space of the globus pallidus, ventral palladum, and substantia nigra in rats at the ED50 and ED85 doses for inhibition of pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced tonic seizures. This suggests that tiagabine prevents the propagation of neural impulses that contribute to seizures by a GABA-ergic action.

Tiagabine has shown efficacy in several animal models of seizures. It is effective against the tonic phase of subcutaneous PTZ-induced seizures in mice and rats, seizures induced by the proconvulsant DMCM in mice, audiogenic seizures in genetically epilepsy-prone rats (GEPR), and amygdala-kindled seizures in rats. Tiagabine has little efficacy against maximal electroshock seizures in rats and is only partially effective against subcutaneous PTZ-induced clonic seizures in mice, picrotoxin-induced tonic seizures in the mouse, bicuculline-induced seizures in the rat, and photic seizures in photosensitive baboons. Tiagabine produces a biphasic dose-response curve against PTZ- and DMCM-induced convulsions, with attenuated effectiveness at higher doses.

Based on in vitro binding studies, tiagabine does not significantly inhibit the uptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, glutamate, or choline and shows little or no binding to dopamine D1 and D2, muscarinic, serotonin 5HT1A, 5HT2, and 5HT3, beta-1 and 2 adrenergic, alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenergic, histamine H2 and H3, adenosine A1 and A2, opiate µ and K1, NMDA glutamate, and GABAA receptors at 100 µM. It also lacks significant affinity for sodium or calcium channels. Tiagabine binds to histamine H1, serotonin 5HT1B, benzodiazepine, and chloride channel receptors at concentrations 20 to 400 times those inhibiting the uptake of GABA.

Pharmacokinetics

Tiagabine is well absorbed, with food slowing absorption rate but not altering the extent of absorption. The elimination half-life of tiagabine is 7 to 9 hours in normal volunteers. In epilepsy clinical trials, most patients were receiving hepatic enzyme-inducing agents (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone, and phenobarbital). The pharmacokinetic profile in induced patients is significantly different from the non-induced population (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Use in Non-Induced Patients). The systemic clearance of tiagabine in induced patients is approximately 60% greater resulting in considerably lower plasma concentrations and an elimination half-life of 2 to 5 hours. Given this difference in clearance, the systemic exposure after a dose of 32 mg/day in an induced population is expected to be comparable to the systemic exposure after a dose of 12 mg/day in a non-induced population. Similarly, the systemic exposure after a dose of 56 mg/day in an induced population is expected to be comparable to the systemic exposure after a dose of 22 mg/day in a non-induced population.

Absorption and Distribution

Absorption of tiagabine is rapid, with peak plasma concentrations occurring at approximately 45 minutes following an oral dose in the fasting state. Tiagabine is nearly completely absorbed (>95%), with an absolute oral bioavailability of about 90%. A high fat meal decreases the rate (mean Tmax was prolonged to 2.5 hours, and mean Cmax was reduced by about 40%) but not the extent (AUC) of tiagabine absorption. In all clinical trials, tiagabine was given with meals.

The pharmacokinetics of tiagabine are linear over the single dose range of 2 to 24 mg. Following multiple dosing, steady state is achieved within 2 days.

Tiagabine is 96% bound to human plasma proteins, mainly to serum albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein over the concentration range of 10 ng/mL to 10,000 ng/mL. While the relationship between tiagabine plasma concentrations and clinical response is not currently understood, trough plasma concentrations observed in controlled clinical trials at doses from 30 to 56 mg/day ranged from <1 ng/mL to 234 ng/mL.

Metabolism and Elimination

Although the metabolism of tiagabine has not been fully elucidated, in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that at least two metabolic pathways for tiagabine have been identified in humans: 1) thiophene ring oxidation leading to the formation of 5-oxo-tiagabine; and 2) glucuronidation. The 5-oxo-tiagabine metabolite does not contribute to the pharmacologic activity of tiagabine.

Based on in vitro data, tiagabine is likely to be metabolized primarily by the 3A isoform subfamily of hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP 3A), although contributions to the metabolism of tiagabine from CYP 1A2, CYP 2D6 or CYP 2C19 have not been excluded.

Approximately 2% of an oral dose of tiagabine is excreted unchanged, with 25% and 63% of the remaining dose excreted into the urine and feces, respectively, primarily as metabolites, at least 2 of which have not been identified. The mean systemic plasma clearance is 109 mL/min (CV = 23%) and the average elimination half-life for tiagabine in healthy subjects ranged from 7 to 9 hours. The elimination half-life decreased by 50 to 65% in hepatic enzyme-induced patients with epilepsy compared to uninduced patients with epilepsy.

A diurnal effect on the pharmacokinetics of tiagabine was observed. Mean steady-state Cmin values were 40% lower in the evening than in the morning. Tiagabine steady-state AUC values were also found to be 15% lower following the evening tiagabine dose compared to the AUC following the morning dose.

Special Populations

Renal Insufficiency

The pharmacokinetics of total and unbound tiagabine were similar in subjects with normal renal function (creatinine clearance >80 mL/min) and in subjects with mild (creatinine clearance 40 to 80 mL/min), moderate (creatinine clearance 20 to 39 mL/min), or severe (creatinine clearance 5 to 19 mL/min) renal impairment. The pharmacokinetics of total and unbound tiagabine were also unaffected in subjects with renal failure requiring hemodialysis.

Hepatic Insufficiency

In patients with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh Class B), clearance of unbound tiagabine was reduced by about 60%. Patients with impaired liver function may require reduced initial and maintenance doses of tiagabine and/or longer dosing intervals compared to patients with normal hepatic function (see PRECAUTIONS).

Geriatric

The pharmacokinetic profile of tiagabine was similar in healthy elderly and healthy young adults.

Pediatric

Tiagabine has not been investigated in adequate and well-controlled clinical trials in patients below the age of 12. The apparent clearance and volume of distribution of tiagabine per unit body surface area or per kg were fairly similar in 25 children (age: 3 to 10 years) and in adults taking enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs ([AEDs] e.g., carbamazepine or phenytoin). In children who were taking a non-inducing AED (e.g., valproate), the clearance of tiagabine based upon body weight and body surface area was 2 and 1.5-fold higher, respectively, than in non-induced adults with epilepsy.

Gender, Race and Cigarette Smoking

No specific pharmacokinetic studies were conducted to investigate the effect of gender, race and cigarette smoking on the disposition of tiagabine. Retrospective pharmacokinetic analyses, however, suggest that there is no clinically important difference between the clearance of tiagabine in males and females, when adjusted for body weight. Population pharmacokinetic analyses indicated that tiagabine clearance values were not significantly different in Caucasian (N=463), Black (N=23), or Hispanic (N=17) patients with epilepsy, and that tiagabine clearance values were not significantly affected by tobacco use.

Interactions with other Antiepilepsy Drugs

The clearance of tiagabine is affected by the co-administration of hepatic enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs. Tiagabine is eliminated more rapidly in patients who have been taking hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs, e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone and phenobarbital than in patients not receiving such treatment (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions).

-

CLINICAL STUDIES

The effectiveness of tiagabine hydrochloride as adjunctive therapy (added to other antiepilepsy drugs) was examined in three multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, clinical trials in 769 patients with refractory partial seizures who were taking at least one hepatic enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drug (AED), and two placebo-controlled cross-over studies in 90 patients. In the parallel-group trials, patients had a history of at least six complex partial seizures (Study 1 and Study 2, U.S. studies), or six partial seizures of any type (Study 3, European study), occurring alone or in combination with any other seizure type within the 8-week period preceding the first study visit in spite of receiving one or more AEDs at therapeutic concentrations.

In the first two studies, the primary protocol-specified outcome measure was the median reduction from baseline in the 4-week complex partial seizure (CPS) rates during treatment. In the third study, the protocol-specified primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients achieving a 50% or greater reduction from baseline in the 4-week seizure rate of all partial seizures during treatment. The results given below include data for complex partial seizures and all partial seizures for the intent-to-treat population (all patients who received at least one dose of treatment and at least one seizure evaluation) in each study.

Study 1 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial comparing tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg/day, tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg/day, tiagabine hydrochloride 56 mg/day, and placebo. Study drug was given as a four times a day regimen. After a prospective Baseline Phase of 12 weeks, patients were randomized to one of the four treatment groups described above. The 16-week Treatment Phase consisted of a 4-week Titration Period, followed by a 12-week Fixed-Dose Period, during which concomitant AED doses were held constant. The primary outcome was assessed for the combined 32 and 56 mg/day groups compared to placebo.

Study 2 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial consisting of an 8-week Baseline Phase and a 12-week Treatment Phase, the first 4 weeks of which constituted a Titration Period and the last 8 weeks a Fixed-Dose Period. This study compared tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg BID and 8 mg QID to placebo. The protocol-specified primary outcome measure was assessed separately for each group treated with tiagabine hydrochloride.

The following tables display the results of the analyses of these two trials.

Table 1: Median Reduction and Median Percent Reduction from Baseline in 4-Week Seizure Rates in Study 1 Placebo

(N=91)Tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg/day

(N=61)Tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg/day

(N=87)Tiagabine hydrochloride 56 mg/day

(N=56)Combined 32 and 56 mg/day

(N=143)- * p < 0.05

- † Statistical significance was not assessed for median % reduction.

Complex Partial Median Reduction 0.6 0.8 2.2* 2.9* 2.6* Median % Reduction† 9% 13% 25% 32% 29% All Partial Median Reduction 0.2 1.2 2.7* 3.5* 2.9* Median % Reduction† 3% 12% 24% 36% 27% Table 2: Median Reduction and Median Percent Reduction from Baseline in 4-Week Seizure Rates in Study 2 Placebo

(N=107)Tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg BID

(N=106)Tiagabine hydrochloride 8 mg QID

(N=104)- * p < 0.027, necessary for statistical significance due to multiple comparisons.

- † Statistical significance was not assessed for median % reduction.

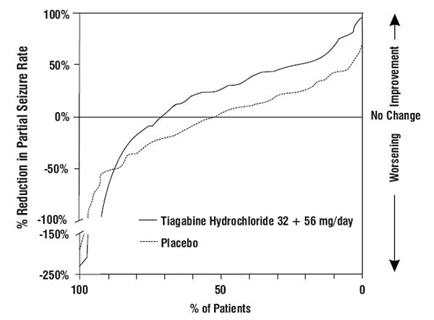

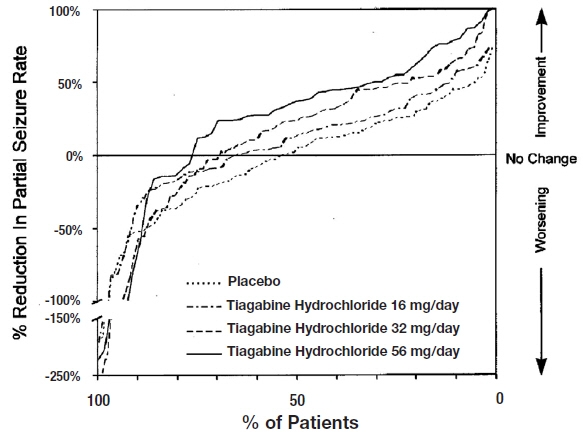

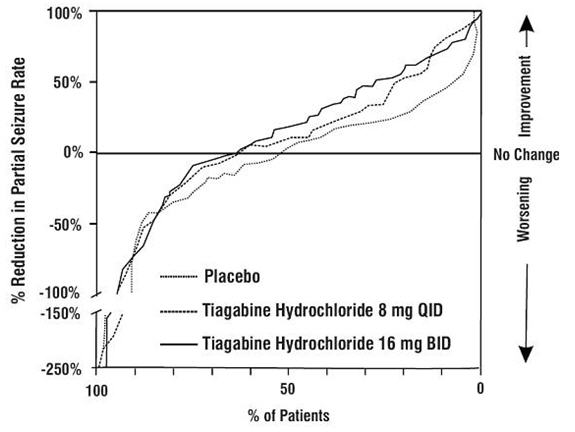

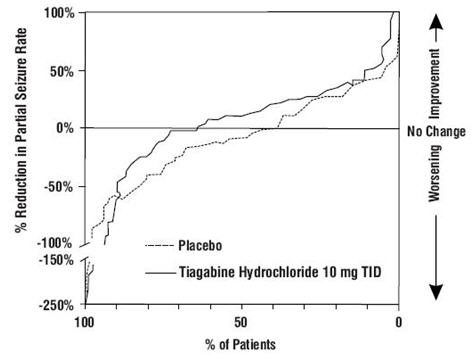

Complex Partial Median Reduction 0.3 1.6 1.3* Median % Reduction† 4% 22% 15% All Partial Median Reduction 0.5 1.6 1.3 Median % Reduction† 5% 19% 13% Figures 1 to 4 present the proportion of patients (X-axis) whose percent reduction from baseline in the all partial seizure rate was at least as great as that indicated on the Y axis in the three placebo-controlled adjunctive studies (Studies 1, 2, and 3). A positive value on the Y axis indicates an improvement from baseline (i.e., a decrease in seizure rate), while a negative value indicates a worsening from baseline (i.e., an increase in seizure rate). Thus, in a display of this type, the curve for an effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for placebo.

Figure 1 indicates that the proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in seizure rate was consistently higher for the combined tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg and 56 mg groups compared to the placebo group in Study 1. For example, Figure 1 indicates that approximately 24% of patients treated with tiagabine hydrochloride experienced a 50% or greater reduction, compared to 4% in the placebo group.

Figure 1

Study 1

Figure 2 also displays the results for Study 1, which was a dose-response study, by treatment group, without combining tiagabine hydrochloride dosage groups. Figure 2 indicates a dose-response relationship across the three tiagabine hydrochloride groups. The proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in all partial seizure rates was consistently higher as the dose of tiagabine hydrochloride was increased. For example, Figure 2 indicates that approximately 4% of patients in the placebo group experienced a 50% or greater reduction in all partial seizure rate, compared to approximately 10% of the tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg/day group, 21% of the tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg/day group, and 30% of the tiagabine hydrochloride 56 mg/day group.

Figure 2

Study 1

Figure 3 indicates that the proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in partial seizure rate was consistently greater in patients taking tiagabine hydrochloride than in those taking placebo in Study 2 (Study 2 compared placebo to tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg/day; one of the tiagabine hydrochloride groups received 8 mg QID, while the other tiagabine hydrochloride group received 16 mg BID). For example, Figure 3 indicates that approximately 7% of patients in the placebo group experienced a 50% or greater reduction in their partial seizure rate, compared to approximately 23% of patients in the tiagabine hydrochloride 8 mg QID group and 28% of patients in the tiagabine hydrochloride 16 mg BID group.

Figure 3

Study 2

Study 3 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial that compared tiagabine hydrochloride 10 mg TID (N=77) with placebo (N=77). In this trial, patients were followed prospectively during a 12-week Baseline Phase and then randomized to receive study drug during an 18-week Treatment Phase. During the first 6 weeks of treatment (Titration Period), patients were titrated to 30 mg/day, after which they were maintained on this dose during the 12-week Fixed-Dose Period. The protocol-specified primary outcome measure (proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% reduction from baseline in partial seizure rate) did not reach statistical significance. However, analyses of the median reduction from baseline in 4-week partial seizure rate (the analyses presented above for Study 1 and Study 2) were performed and showed a statistically significant improvement compared to placebo in all partial and complex partial seizure rates (Table 3):

Table 3: Median Reduction and Median Percent Reduction from Baseline in 4-Week Seizure Rates in Study 3 Placebo

(N=77)Tiagabine hydrochloride 30 mg/day

(N=77)- * N=72 and 75 for placebo and Tiagabine hydrochloride, respectively.

- † p < 0.05

- ‡ Statistical significance was not assessed for median % reduction.

Complex Partial* Median Reduction -0.1 1.3† Median % Reduction‡ -1% 14% All Partial Median Reduction -0.5 1.1† Median % Reduction‡ -7% 11% Figure 4 indicates that the proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in seizure activity was consistently higher in those taking tiagabine hydrochloride than those taking placebo in Study 3. For example, Figure 4 indicates that approximately 5% of patients in the placebo group experienced a 50% or greater reduction in their partial seizure rate compared to approximately 10% of patients in the tiagabine hydrochloride group.

Figure 4

Study 3

The two other placebo-controlled trials that examined the effectiveness of tiagabine hydrochloride were small cross-over trials (N=46 and 44). Both trials included an open Screening Phase during which patients were titrated to an optimal dose and then treated with this dose for an additional 4 weeks. After this Open Phase, patients were randomized to one of two blinded treatment sequences (tiagabine hydrochloride followed by placebo or placebo followed by tiagabine hydrochloride). The Double-Blind Phase consisted of two Treatment Periods, each lasting 7 weeks (with a 3 week washout between periods). The outcome measures were median with-in patient differences between placebo and tiagabine hydrochloride Treatment Periods in 4-week complex partial and all partial seizure rates. The reductions in seizure rates were statistically significant in both studies.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Seizures in Patients Without Epilepsy: Post-marketing reports have shown that tiagabine hydrochloride use has been associated with new onset seizures and status epilepticus in patients without epilepsy. Dose may be an important predisposing factor in the development of seizures, although seizures have been reported in patients taking daily doses of tiagabine hydrochloride as low as 4 mg/day. In most cases, patients were using concomitant medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, stimulants, narcotics) that are thought to lower the seizure threshold. Some seizures occurred near the time of a dose increase, even after periods of prior stable dosing.

The tiagabine hydrochloride dosing recommendations in current labeling for treatment of epilepsy were based on use in patients with partial seizures 12 years of age and older, most of whom were taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs; e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone and phenobarbital) which lower plasma levels of tiagabine hydrochloride by inducing its metabolism. Use of tiagabine hydrochloride without enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs results in blood levels about twice those attained in the studies on which current dosing recommendations are based (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Safety and effectiveness of tiagabine hydrochloride have not been established for any indication other than as adjunctive therapy for partial seizures in adults and children 12 years and older.

In nonepileptic patients who develop seizures while on tiagabine hydrochloride treatment, tiagabine hydrochloride should be discontinued and patients should be evaluated for an underlying seizure disorder.

Seizures and status epilepticus are known to occur with tiagabine hydrochloride overdosage (see OVERDOSAGE).

Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including tiagabine hydrochloride, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI:1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5-100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed.

Table 4 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 4: Risk by Indication for Antiepileptic Drugs in the Pooled Analysis Indication Placebo Patients with Events per 1000 Patients Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients Relative Risk: Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients Epilepsy 1.0 3.4 3.5 2.4 Psychiatric 5.7 8.5 1.5 2.9 Other 1.0 1.8 1.9 0.9 Total 2.4 4.3 1.8 1.9 The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing tiagabine hydrochloride or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

Withdrawal Seizures

As a rule, antiepilepsy drugs should not be abruptly discontinued because of the possibility of increasing seizure frequency. In a placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-response study (Study 1 described in CLINICAL STUDIES) designed, in part, to investigate the capacity of tiagabine hydrochloride to induce withdrawal seizures, study drug was tapered over a 4-week period after 16 weeks of treatment. Patients' seizure frequency during this 4-week withdrawal period was compared to their baseline seizure frequency (before study drug). For each partial seizure type, for all partial seizure types combined, and for secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures, more patients experienced increases in their seizure frequencies during the withdrawal period in the three tiagabine hydrochloride groups than in the placebo group. The increase in seizure frequency was not affected by dose. Tiagabine hydrochloride should be withdrawn gradually to minimize the potential of increased seizure frequency, unless safety concerns require a more rapid withdrawal.

Cognitive/Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events

Adverse events most often associated with the use of tiagabine hydrochloride were related to the central nervous system. The most significant of these can be classified into 2 general categories: 1) impaired concentration, speech or language problems, and confusion (effects on thought processes); and 2) somnolence and fatigue (effects on level of consciousness). The majority of these events were mild to moderate. In controlled clinical trials, these events led to discontinuation of treatment with tiagabine hydrochloride in 6% (31 of 494) of patients compared to 2% (5 of 275) of the placebo-treated patients. A total of 1.6% (8 of 494) of the tiagabine hydrochloride treated patients in the controlled trials were hospitalized secondary to the occurrence of these events compared to 0% of the placebo treated patients. Some of these events were dose related and usually began during initial titration.

Patients with a history of spike and wave discharges on EEG have been reported to have exacerbations of their EEG abnormalities associated with these cognitive/neuropsychiatric events. This raises the possibility that these clinical events may, in some cases, be a manifestation of underlying seizure activity (see PRECAUTIONS, Laboratory Tests, EEG). In the documented cases of spike and wave discharges on EEG with cognitive/neuropsychiatric events, patients usually continued tiagabine, but required dosage adjustment.

Additionally, there have been postmarketing reports of patients who have experienced cognitive/neuropsychiatric symptoms, some accompanied by EEG abnormalities such as generalized spike and wave activity, that have been reported as nonconvulsant status epilepticus. Some reports describe recovery following reduction of dose or discontinuation of tiagabine hydrochloride.

Status Epilepticus

In the three double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies (Studies 1, 2, and 3), the incidence of any type of status epilepticus (simple, complex, or generalized tonic-clonic) in patients receiving tiagabine hydrochloride was 0.8% (4 of 494 patients) versus 0.7% (2 of 275 patients) receiving placebo. Among the patients treated with tiagabine hydrochloride across all epilepsy studies (controlled and uncontrolled), 5% had some form of status epilepticus. Of the 5%, 57% of patients experienced complex partial status epilepticus. A critical risk factor for status epilepticus was the presence of a previous history; 33% of patients with a history of status epilepticus had recurrence during tiagabine hydrochloride treatment. Because adequate information about the incidence of status epilepticus in a similar population of patients with epilepsy who have not received treatment with tiagabine hydrochloride is not available, it is impossible to state whether or not treatment with tiagabine hydrochloride is associated with a higher or lower rate of status epilepticus than would be expected to occur in a similar population not treated with tiagabine hydrochloride.

Sudden Unexpected Death In Epilepsy (SUDEP)

There have been as many as 10 cases of sudden unexpected deaths during the clinical development of tiagabine among 2531 patients with epilepsy (3831 patient-years of exposure).

This represents an estimated incidence of 0.0026 deaths per patient-year. This rate is within the range of estimates for the incidence of sudden and unexpected deaths in patients with epilepsy not receiving tiagabine hydrochloride (ranging from 0.0005 for the general population with epilepsy, 0.003 to 0.004 for clinical trial populations similar to that in the clinical development program for tiagabine hydrochloride, to 0.005 for patients with refractory epilepsy). The estimated SUDEP rates in patients receiving tiagabine hydrochloride are also similar to those observed in patients receiving other antiepilepsy drugs, chemically unrelated to tiagabine hydrochloride that underwent clinical testing in similar populations at about the same time. This evidence suggests that the SUDEP rates reflect population rates, not a drug effect.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Use in Non-Induced Patients

Virtually all experience with tiagabine hydrochloride has been obtained in patients with epilepsy receiving at least one concomitant enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drug (AED), which lowers the plasma levels of tiagabine. Use in non-induced patients requires lower doses of tiagabine hydrochloride. These patients may also require a slower titration of tiagabine hydrochloride compared to that of induced patients (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Patients taking a combination of inducing and non-inducing agents (e.g., carbamazepine and valproate) should be considered to be induced. Patients not receiving hepatic enzyme-inducing agents are referred to as non-induced patients.

Generalized Weakness

Moderately severe to incapacitating generalized weakness has been reported following administration of tiagabine hydrochloride in 28 of 2531 (approximately 1%) patients with epilepsy. The weakness resolved in all cases after a reduction in dose or discontinuation of tiagabine hydrochloride.

Binding in the Eye and Other Melanin-Containing Tissues

When dogs received a single dose of radiolabeled tiagabine, there was evidence of residual binding in the retina and uvea after 3 weeks (the latest time point measured). Although not directly measured, melanin binding is suggested. The ability of available tests to detect potentially adverse consequences, if any, of the binding of tiagabine to melanin-containing tissue is unknown and there was no systematic monitoring for relevant ophthalmological changes during the clinical development of tiagabine hydrochloride. However, long term (up to one year) toxicological studies of tiagabine in dogs showed no treatment-related ophthalmoscopic changes and macro- and microscopic examinations of the eye were unremarkable. Accordingly, although there are no specific recommendations for periodic ophthalmologic monitoring, prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects.

Use in Hepatically-Impaired Patients

Because the clearance of tiagabine is reduced in patients with liver disease, dosage reduction may be necessary in these patients.

Serious Rash

Four patients treated with tiagabine during the product's premarketing clinical testing developed what were considered to be serious rashes. In two patients, the rash was described as maculopapular; in one it was described as vesiculobullous; and in the 4th case, a diagnosis of Stevens Johnson Syndrome was made. In none of the 4 cases is it certain that tiagabine was the primary, or even a contributory, cause of the rash. Nevertheless, drug associated rash can, if extensive and serious, cause irreversible morbidity, even death.

Information for Patients

Patients should be informed of the availability of a Medication Guide, and they should be instructed to read it prior to taking tiagabine hydrochloride. The complete text of the Medication Guide is provided at the end of this labeling.

Suicidal Thinking and Behavior

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be counseled that AEDs, including tiagabine hydrochloride, may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

Patients should be advised that tiagabine hydrochloride may cause dizziness, somnolence, and other symptoms and signs of CNS depression. Accordingly, patients should be advised neither to drive nor to operate other complex machinery until they have gained sufficient experience on tiagabine hydrochloride to gauge whether or not it affects their mental and/or motor performance adversely. Because of the possible additive depressive effects, caution should also be used when patients are taking other CNS depressants in combination with tiagabine hydrochloride.

Because teratogenic effects were seen in the offspring of rats exposed to maternally toxic doses of tiagabine and because experience in humans is limited, patients should be advised to notify their physicians if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy.

Because of the possibility that tiagabine may be excreted in breast milk, patients should be advised to notify those providing care to themselves and their children if they intend to breast-feed or are breast-feeding an infant.

Patients should be encouraged to enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry if they become pregnant. This registry is collecting information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. To enroll, patients can call the toll free number 1-888-233-2334 (see PRECAUTIONS, Pregnancy).

Laboratory Tests

Therapeutic Monitoring of Plasma Concentrations of Tiagabine

A therapeutic range for tiagabine plasma concentrations has not been established. In controlled trials, trough plasma concentrations observed among patients randomized to doses of tiagabine that were statistically significantly more effective than placebo ranged from <1 ng/mL to 234 ng/mL (median, 10th and 90th percentiles are 23.7 ng/mL, 5.4 ng/mL, and 69.8 ng/mL, respectively). Because of the potential for pharmacokinetic interactions between tiagabine hydrochloride and drugs that induce or inhibit hepatic metabolizing enzymes, it may be useful to obtain plasma levels of tiagabine before and after changes are made in the therapeutic regimen.

Clinical Chemistry and Hematology

During the development of tiagabine hydrochloride, no systematic abnormalities on routine laboratory testing were noted. Therefore, no specific guidance is offered regarding routine monitoring; the practitioner retains responsibility for determining how best to monitor the patient in his/her care.

EEG

Patients with a history of spike and wave discharges on EEG have been reported to have exacerbations of their EEG abnormalities associated with cognitive/neuropsychiatric events. This raises the possibility that these clinical events may, in some cases, be a manifestation of underlying seizure activity (see WARNINGS, Cognitive/Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events). In the documented cases of spike and wave discharges on EEG with cognitive/neuropsychiatric events, patients usually continued tiagabine, but required dosage adjustment.

Drug Interactions

In evaluating the potential for interactions among co-administered antiepilepsy drugs (AEDs), whether or not an AED induces or does not induce metabolic enzymes is an important consideration. Carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone, and phenobarbital are generally classified as enzyme inducers; valproate and gabapentin are not. Tiagabine hydrochloride is considered to be a non-enzyme inducing AED (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Use in Non-Induced Patients).

The drug interaction data described in this section were obtained from studies involving either healthy subjects or patients with epilepsy.

Effects of Tiagabine hydrochloride on other Antiepilepsy Drugs (AEDs)

Phenytoin

Tiagabine had no effect on the steady-state plasma concentrations of phenytoin in patients with epilepsy.

Carbamazepine

Tiagabine had no effect on the steady-state plasma concentrations of carbamazepine or its epoxide metabolite in patients with epilepsy.

Phenobarbital or Primidone

No formal pharmacokinetic studies have been performed examining the addition of tiagabine to regimens containing phenobarbital or primidone. The addition of tiagabine in a limited number of patients in three well-controlled studies caused no systematic changes in phenobarbital or primidone concentrations when compared to placebo.

Effects of other Antiepilepsy Drugs (AEDs) on Tiagabine hydrochloride

Carbamazepine

Population pharmacokinetic analyses indicate that tiagabine clearance is 60% greater in patients taking carbamazepine with or without other enzyme-inducing AEDs.

Phenytoin

Population pharmacokinetic analyses indicate that tiagabine clearance is 60% greater in patients taking phenytoin with or without other enzyme-inducing AEDs.

Phenobarbital (Primidone)

Population pharmacokinetic analyses indicate that tiagabine clearance is 60% greater in patients taking phenobarbital (primidone) with or without other enzyme-inducing AEDs.

Valproate

The addition of tiagabine to patients taking valproate chronically had no effect on tiagabine pharmacokinetics, but valproate significantly decreased tiagabine binding in vitro from 96.3 to 94.8%, which resulted in an increase of approximately 40% in the free tiagabine concentration. The clinical relevance of this in vitro finding is unknown.

Interaction of Tiagabine hydrochloride with Other Drugs

Cimetidine

Co-administration of cimetidine (800 mg/day) to patients taking tiagabine chronically had no effect on tiagabine pharmacokinetics.

Theophylline

A single 10 mg dose of tiagabine did not affect the pharmacokinetics of theophylline at steady state.

Warfarin

No significant differences were observed in the steady-state pharmacokinetics of R-warfarin or S-warfarin with the addition of tiagabine given as a single dose. Prothrombin times were not affected by tiagabine.

Digoxin

Concomitant administration of tiagabine did not affect the steady-state pharmacokinetics of digoxin or the mean daily trough serum level of digoxin.

Ethanol or Triazolam

No significant differences were observed in the pharmacokinetics of triazolam (0.125 mg) and tiagabine (10 mg) when given together as a single dose. The pharmacokinetics of ethanol were not affected by multiple-dose administration of tiagabine. Tiagabine has shown no clinically important potentiation of the pharmacodynamic effects of triazolam or alcohol. Because of the possible additive effects of drugs that may depress the nervous system, ethanol or triazolam should be used cautiously in combination with tiagabine.

Oral Contraceptives

Multiple dose administration of tiagabine (8 mg/day monotherapy) did not alter the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptives in healthy women of child-bearing age.

Interaction of Tiagabine hydrochloride with Highly Protein Bound Drugs

In vitro data showed that tiagabine is 96% bound to human plasma protein and therefore has the potential to interact with other highly protein bound compounds. Such an interaction can potentially lead to higher free fractions of either tiagabine or the competing drug.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

In rats, a study of the potential carcinogenicity associated with tiagabine hydrochloride administration showed that 200 mg/kg/day (plasma exposure [AUC] 36 to 100 times that at the maximum recommended human dosage [MRHD] of 56 mg/day) for 2 years resulted in small, but statistically significant increases in the incidences of hepatocellular adenomas in females and Leydig cell tumors of the testis in males. The significance of these findings relative to the use of tiagabine hydrochloride in humans is unknown. The no effect dosage for induction of tumors in this study was 100 mg/kg/day (17 to 50 times the exposure at the MRHD). No statistically significant increases in tumor formation were noted in mice at dosages up to 250 mg/kg/day (20 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

Mutagenesis

Tiagabine produced an increase in structural chromosome aberration frequency in human lymphocytes in vitro in the absence of metabolic activation. No increase in chromosomal aberration frequencies was demonstrated in this assay in the presence of metabolic activation. No evidence of genetic toxicity was found in the in vitro bacterial gene mutation assays, the in vitro HGPRT forward mutation assay in Chinese hamster lung cells, the in vivo mouse micronucleus test, or an unscheduled DNA synthesis assay.

Impairment of Fertility

Studies of male and female rats administered dosages of tiagabine hydrochloride prior to and during mating, gestation, and lactation have shown no impairment of fertility at doses up to 100 mg/kg/day. This dose represents approximately 16 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 56 mg/day, based on body surface area (mg/m2). Lowered maternal weight gain and decreased viability and growth in the rat pups were found at 100 mg/kg, but not at 20 mg/kg/day (3 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C

Tiagabine has been shown to have adverse effects on embryo-fetal development, including teratogenic effects, when administered to pregnant rats and rabbits at doses greater than the human therapeutic dose.

An increased incidence of malformed fetuses (various craniofacial, appendicular, and visceral defects) and decreased fetal weights were observed following oral administration of 100 mg/kg/day to pregnant rats during the period of organogenesis. This dose is approximately 16 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 56 mg/day, based on body surface area (mg/m2). Maternal toxicity (transient weight loss/reduced maternal weight gain during gestation) was associated with this dose, but there is no evidence to suggest that the teratogenic effects were secondary to the maternal effects. No adverse maternal or embryo-fetal effects were seen at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day (3 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

Decreased maternal weight gain, increased resorption of embryos and increased incidences of fetal variations, but not malformations, were observed when pregnant rabbits were given 25 mg/kg/day (8 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) during organogenesis. The no effect level for maternal and embryo-fetal toxicity in rabbits was 5 mg/kg/day (equivalent to the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

When female rats were given tiagabine 100 mg/kg/day during late gestation and throughout parturition and lactation, decreased maternal weight gain during gestation, an increase in stillbirths, and decreased postnatal offspring viability and growth were found. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Tiagabine should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

To provide additional information regarding the effects of in utero exposure to tiagabine hydrochloride, physicians are advised to recommend that pregnant patients taking tiagabine hydrochloride enroll in the NAAED Pregnancy Registry. This can be done by calling the toll free number 1-888-233-2334, and must be done by patients themselves. Information on the registry can also be found at the website http://www.aedpregnancyregistry.org/.

Use in Nursing Mothers

Studies in rats have shown that tiagabine hydrochloride and/or its metabolites are excreted in the milk of that species. Levels of excretion of tiagabine and/or its metabolites in human milk have not been determined and effects on the nursing infant are unknown. Tiagabine hydrochloride should be used in women who are nursing only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients below the age of 12 have not been established. The pharmacokinetics of tiagabine were evaluated in pediatric patients age 3 to 10 years (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populations, Pediatric).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most commonly observed adverse events in placebo-controlled, parallel-group, add-on epilepsy trials associated with the use of tiagabine hydrochloride in combination with other antiepilepsy drugs not seen at an equivalent frequency among placebo-treated patients were dizziness/light-headedness, asthenia/lack of energy, somnolence, nausea, nervousness/irritability, tremor, abdominal pain, and thinking abnormal/difficulty with concentration or attention.

Approximately 21% of the 2531 patients who received tiagabine hydrochloride in clinical trials of epilepsy discontinued treatment because of an adverse event. The adverse events most commonly associated with discontinuation were dizziness (1.7%), somnolence (1.6%), depression (1.3%), confusion (1.1%), and asthenia (1.1%).

In Studies 1 and 2 (U.S. studies), the double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, add-on studies, the proportion of patients who discontinued treatment because of adverse events was 11% for the group treated with tiagabine hydrochloride and 6% for the placebo group. The most common adverse events considered the primary reason for discontinuation were confusion (1.2%), somnolence (1.0%), and ataxia (1.0%).

Adverse Event Incidence in Controlled Clinical Trials

Table 5 lists treatment-emergent signs and symptoms that occurred in at least 1% of patients treated with tiagabine hydrochloride for epilepsy participating in parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials and were numerically more common in the tiagabine hydrochloride group. In these studies, either tiagabine hydrochloride or placebo was added to the patient's current antiepilepsy drug therapy. Adverse events were usually mild or moderate in intensity.

The prescriber should be aware that these figures, obtained when tiagabine hydrochloride was added to concurrent antiepilepsy drug therapy, cannot be used to predict the frequency of adverse events in the course of usual medical practice when patient characteristics and other factors may differ from those prevailing during clinical studies. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be directly compared with figures obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, or investigators. An inspection of these frequencies, however, does provide the prescribing physician with one basis to estimate the relative contribution of drug and non-drug factors to the adverse event incidences in the population studied.

Table 5: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Event* Incidence in Parallel-Group, Placebo-Controlled, Add-On Trials (events in at least 1% of patients treated with tiagabine hydrochloride and numerically more frequent than in the placebo group) Body System/

COSTARTTiagabine hydrochloride

N=494

%Placebo

N=275

%Body as a Whole - * Patients in these add-on studies were receiving one to three concomitant enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs in addition to tiagabine hydrochloride or placebo. Patients may have reported multiple adverse experiences; thus, patients may be included in more than one category.

- † COSTART term substituted with a more clinically descriptive term.

Abdominal Pain 7 3 Pain (unspecified) 5 3 Cardiovascular Vasodilation 2 1 Digestive Nausea 11 9 Diarrhea 7 3 Vomiting 7 4 Increased Appetite 2 0 Mouth Ulceration 1 0 Musculoskeletal Myasthenia 1 0 Nervous System Dizziness 27 15 Asthenia 20 14 Somnolence 18 15 Nervousness 10 3 Tremor 9 3 Difficulty with Concentration/Attention† 6 2 Insomnia 6 4 Ataxia 5 3 Confusion 5 3 Speech Disorder 4 2 Difficulty with Memory† 4 3 Paresthesia 4 2 Depression 3 1 Emotional Lability 3 2 Abnormal Gait 3 2 Hostility 2 1 Nystagmus 2 1 Language Problems† 2 0 Agitation 1 0 Respiratory System Pharyngitis 7 4 Cough Increased 4 3 Skin and Appendages Rash 5 4 Pruritus 2 0 Other events reported by 1% or more of patients treated with tiagabine hydrochloride but equally or more frequent in the placebo group were: accidental injury, chest pain, constipation, flu syndrome, rhinitis, anorexia, back pain, dry mouth, flatulence, ecchymosis, twitching, fever, amblyopia, conjunctivitis, urinary tract infection, urinary frequency, infection, dyspepsia, gastroenteritis, nausea and vomiting, myalgia, diplopia, headache, anxiety, acne, sinusitis, and incoordination.

Study 1 was a dose-response study including doses of 32 mg and 56 mg. Table 6 shows adverse events reported at a rate of ≥ 5% in at least one tiagabine hydrochloride group and more frequent than in the placebo group. Among these events, depression, tremor, nervousness, difficulty with concentration/attention, and perhaps asthenia exhibited a positive relationship to dose.

Table 6: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Event Incidence in Study 1* (events in at least 5% of patients treated with Tiagabine hydrochloride 32 or 56 mg and numerically more frequent than in the placebo group) Body System/COSTART Term Tiagabine hydrochloride 56 mg

(N=57)

%Tiagabine hydrochloride 32 mg

(N=88)

%Placebo

(N=91)

%Body as a Whole - * Patients in this study were receiving one to three concomitant enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs in addition to tiagabine hydrochloride or placebo. Patients may have reported multiple adverse experiences; thus, patients may be included in more than one category.

- † COSTART term substituted with a more clinically descriptive term.

Accidental Injury 21 15 20 Infection 19 10 12 Flu Syndrome 9 6 3 Pain 7 2 3 Abdominal Pain 5 7 4 Digestive System Diarrhea 2 10 6 Hemic and Lymphatic System Ecchymosis 0 6 1 Musculoskeletal System Myalgia 5 2 3 Nervous System Dizziness 28 31 12 Asthenia 23 18 15 Tremor 21 14 1 Somnolence 19 21 17 Nervousness 14 11 6 Difficulty with Concentration/Attention† 14 7 3 Ataxia 9 6 6 Depression 7 1 0 Insomnia 5 6 3 Abnormal Gait 5 5 3 Hostility 5 5 2 Respiratory System Pharyngitis 7 8 6 Special Senses Amblyopia 4 9 8 Urogenital System Urinary Tract Infection 5 0 2 The effects of tiagabine hydrochloride in relation to those of placebo on the incidence of adverse events and the types of adverse events reported were independent of age, weight, and gender. Because only 10% of patients were non-Caucasian in parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials, there is insufficient data to support a statement regarding the distribution of adverse experience reports by race.

Other Adverse Events Observed During All Clinical Trials

Tiagabine hydrochloride has been administered to 2531 patients during all phase 2/3 clinical trials, only some of which were placebo-controlled. During these trials, all adverse events were recorded by the clinical investigators using terminology of their own choosing. To provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals having adverse events, similar types of events were grouped into a smaller number of standardized categories using modified COSTART dictionary terminology. These categories are used in the listing below. The frequencies presented represent the proportion of the 2531 patients exposed to tiagabine hydrochloride who experienced events of the type cited on at least one occasion while receiving tiagabine hydrochloride. All reported events are included except those already listed above, events seen only three times or fewer (unless potentially important), events very unlikely to be drug-related, and those too general to be informative. Events are included without regard to determination of a causal relationship to tiagabine.

Events are further classified within body system categories and enumerated in order of decreasing frequency using the following definitions: frequent adverse events are defined as those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse events are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare events are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Body as a Whole: Frequent: Allergic reaction, chest pain, chills, cyst, neck pain, and malaise. Infrequent: Abscess, cellulitis, facial edema, halitosis, hernia, neck rigidity, neoplasm, pelvic pain, photosensitivity reaction, sepsis, sudden death, and suicide attempt.

Cardiovascular System: Frequent: Hypertension, palpitation, syncope, and tachycardia. Infrequent: Angina pectoris, cerebral ischemia, electrocardiogram abnormal, hemorrhage, hypotension, myocardial infarct, pallor, peripheral vascular disorder, phlebitis, postural hypotension, and thrombophlebitis.

Digestive System: Frequent: Gingivitis and stomatitis. Infrequent: Abnormal stools, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, dysphagia, eructation, esophagitis, fecal incontinence, gastritis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, glossitis, gum hyperplasia, hepatomegaly, increased salivation, liver function tests abnormal, melena, periodontal abscess, rectal hemorrhage, thirst, tooth caries, and ulcerative stomatitis.

Endocrine System: Infrequent: Goiter and hypothyroidism.

Hemic and Lymphatic System: Frequent: Lymphadenopathy. Infrequent: Anemia, erythrocytes abnormal, leukopenia, petechia, and thrombocytopenia.

Metabolic and Nutritional: Frequent: Edema, peripheral edema, weight gain, and weight loss. Infrequent: Dehydration, hypercholesteremia, hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia.

Musculoskeletal System: Frequent: Arthralgia. Infrequent: Arthritis, arthrosis, bursitis, generalized spasm, and tendinous contracture.

Nervous System: Frequent: Depersonalization, dysarthria, euphoria, hallucination, hyperkinesia, hypertonia, hypesthesia, hypokinesia, hypotonia, migraine, myoclonus, paranoid reaction, personality disorder, reflexes decreased, stupor, twitching, and vertigo. Infrequent: Abnormal dreams, apathy, choreoathetosis, circumoral paresthesia, CNS neoplasm, coma, delusions, dry mouth, dystonia, encephalopathy, hemiplegia, leg cramps, libido increased, libido decreased, movement disorder, neuritis, neurosis, paralysis, peripheral neuritis, psychosis, reflexes increased, and urinary retention.

Respiratory System: Frequent: Bronchitis, dyspnea, epistaxis, and pneumonia. Infrequent: Apnea, asthma, hemoptysis, hiccups, hyperventilation, laryngitis, respiratory disorder, and voice alteration.

Skin and Appendages: Frequent: Alopecia, dry skin, and sweating. Infrequent: Contact dermatitis, eczema, exfoliative dermatitis, furunculosis, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, hirsutism, maculopapular rash, psoriasis, skin benign neoplasm, skin carcinoma, skin discolorations, skin nodules, skin ulcer, subcutaneous nodule, urticaria, and vesiculobullous rash.

Special Senses: Frequent: Abnormal vision, ear pain, otitis media, and tinnitus. Infrequent: Blepharitis, blindness, deafness, eye pain, hyperacusis, keratoconjunctivitis, otitis externa, parosmia, photophobia, taste loss, taste perversion, and visual field defect.

Urogenital System: Frequent: Dysmenorrhea, dysuria, metrorrhagia, urinary incontinence, and vaginitis. Infrequent: Abortion, amenorrhea, breast enlargement, breast pain, cystitis, fibrocystic breast, hematuria, impotence, kidney failure, menorrhagia, nocturia, papanicolaou smear suspicious, polyuria, pyelonephritis, salpingitis, urethritis, urinary urgency, and vaginal hemorrhage.

Postmarketing Reports

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of tiagabine hydrochloride. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: bullous dermatitis

Eye disorders: vision blurred

- DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

-

OVERDOSAGE

Human Overdose Experience

Human experience of acute overdose with tiagabine hydrochloride is limited. Eleven patients in clinical trials took single doses of tiagabine hydrochloride up to 800 mg. All patients fully recovered, usually within one day. The most common symptoms reported after overdose included somnolence, impaired consciousness, agitation, confusion, speech difficulty, hostility, depression, weakness, and myoclonus. One patient who ingested a single dose of 400 mg experienced generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus, which responded to intravenous phenobarbital.

From post-marketing experience, reports of overdose involving tiagabine hydrochloride alone have included cases in which patients required intubation and ventilatory support as part of the management of their status epilepticus. Overdoses involving multiple drugs, including tiagabine hydrochloride, have resulted in fatal outcomes. Symptoms most often accompanying tiagabine hydrochloride overdose, alone or in combination with other drugs, have included: seizures including status epilepticus in patients with and without underlying seizure disorders, nonconvulsive status epilepticus, respiratory arrest, coma, loss of consciousness, ataxia, dizziness, confusion, somnolence, drowsiness, impaired speech, aggression, agitation, lethargy, myoclonus, spike wave stupor, encephalopathy, amnesia, dyskinesia, tremors, disorientation, psychotic disorder, vomiting, hostility, and temporary paralysis. Respiratory depression was seen in a number of patients, including children, in the context of seizures.

Management of Overdose

There is no specific antidote for overdose with tiagabine hydrochloride. If indicated, elimination of unabsorbed drug should be achieved by emesis or gastric lavage; usual precautions should be observed to maintain the airway. General supportive care of the patient is indicated including monitoring of vital signs and observation of clinical status of the patient. Since tiagabine is mostly metabolized by the liver and is highly protein bound, dialysis is unlikely to be beneficial. A Certified Poison Control Center should be consulted for up to date information on the management of overdose with tiagabine hydrochloride.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

General

The blood level of tiagabine obtained after a given dose depends on whether the patient also is receiving a drug that induces the metabolism of tiagabine. The presence of an inducer means that the attained blood level will be substantially reduced. Dosing should take the presence of concomitant medications into account.

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets are recommended as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial seizures in patients 12 years and older.

The following dosing recommendations apply to all patients taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets:

- Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets are given orally and should be taken with food.

- Do not use a loading dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets.

- Dose titration: Rapid escalation and/or large dose increments of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets should not be used.

- Missed dose(s): If the patient forgets to take the prescribed dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets at the scheduled time, the patient should not attempt to make up for the missed dose by increasing the next dose. If a patient has missed multiple doses, patient should refer back to his or her physician for possible re-titration as clinically indicated.

- Dosage adjustment of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets should be considered whenever a change in patient's enzyme-inducing status occurs as a result of the addition, discontinuation, or dose change of the enzyme-inducing agent.

Induced Adults and Adolescents 12 Years or Older

The following dosing recommendations apply to patients who are already taking enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs (AEDs) (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone, and phenobarbital). Such patients are considered induced patients when administering tiagabine hydrochloride tablets.

In adolescents 12 to 18 years old, tiagabine hydrochloride tablets should be initiated at 4 mg once daily. Modification of concomitant antiepilepsy drugs is not necessary, unless clinically indicated. The total daily dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may be increased by 4 mg at the beginning of Week 2. Thereafter, the total daily dose may be increased by 4 to 8 mg at weekly intervals until clinical response is achieved or up to 32 mg/day. The total daily dose should be given in divided doses two to four times daily. Doses above 32 mg/day have been tolerated in a small number of adolescent patients for a relatively short duration.

In adults, tiagabine hydrochloride tablets should be initiated at 4 mg once daily. Modification of concomitant antiepilepsy drugs is not necessary, unless clinically indicated. The total daily dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may be increased by 4 to 8 mg at weekly intervals until clinical response is achieved or, up to 56 mg/day. The total daily dose should be given in divided doses two to four times daily. Doses above 56 mg/day have not been systematically evaluated in adequate and well-controlled clinical trials.

Experience is limited in patients taking total daily doses above 32 mg/day using twice daily dosing. A typical dosing titration regimen for patients taking enzyme-inducing AEDs (induced patients) is provided in Table 7.

Table 7: Typical Dosing Titration Regimen for Patients Already Taking Enzyme-Inducing AEDs Initiation and Titration Schedule Total Daily Dose Week 1 Initiate at 4 mg once daily 4 mg/day Week 2 Increase total daily dose by 4 mg 8 mg/day

(in two divided doses)Week 3 Increase total daily dose by 4 mg 12 mg/day

(in three divided doses)Week 4 Increase total daily dose by 4 mg 16 mg/day

(in two to four divided doses)Week 5 Increase total daily dose by 4 to 8 mg 20 to 24 mg/day

(in two to four divided doses)Week 6 Increase total daily dose by 4 to 8 mg 24 to 32 mg/day

(in two to four divided doses)Usual Adult Maintenance Dose in Induced Patients: 32 to 56 mg/day in two to four divided doses Non-Induced Adults and Adolescents 12 Years or Older

The following dosing recommendations apply to patients who are taking only non-enzyme-inducing AEDs. Such patients are considered non-induced patients:

Following a given dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, the estimated plasma concentration in the non-induced patients is more than twice that in patients receiving enzyme-inducing agents. Use in non-induced patients requires lower doses of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets. These patients may also require a slower titration of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets compared to that of induced patients (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Pharmacokinetics and PRECAUTIONS, General, Use in Non-Induced Patients).

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets are available in four dosage strengths.

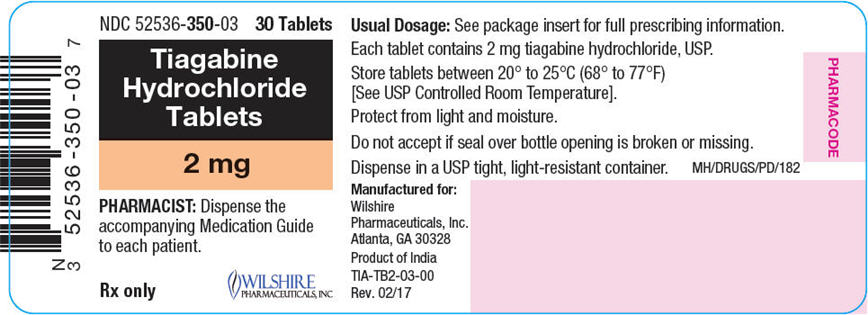

- 2 mg orange-peach, round biconvex, film-coated tablets, debossed with 'ω' on one side and '2' on the other side, are available in bottles of 30 (NDC: 52536-350-03). Each bottle contains a desiccant canister.

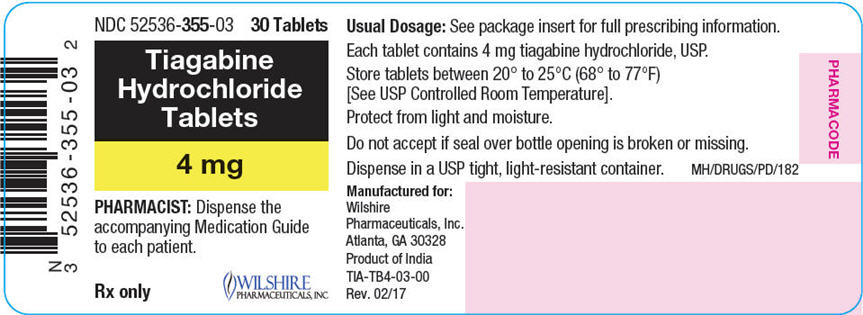

- 4 mg yellow, round, biconvex, film-coated tablets, debossed with 'ω' on one side and '4' on the other side, are available in bottles of 30 (NDC: 52536-355-03). Each bottle contains a desiccant canister.

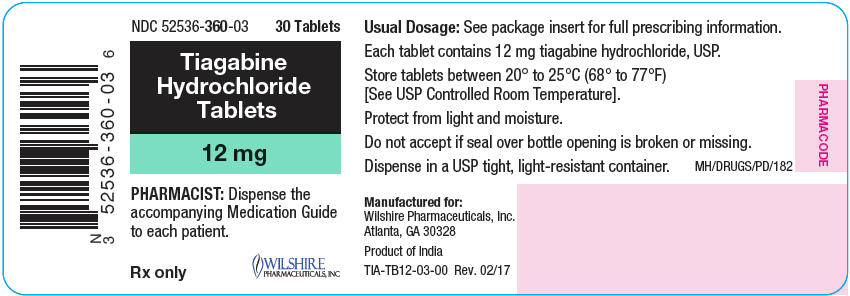

- 12 mg green, oval, biconvex, film-coated tablets, debossed with 'ω' on one side and '12' on the other side are available in bottles of 30 (NDC: 52536-360-03). Each bottle contains a desiccant canister.

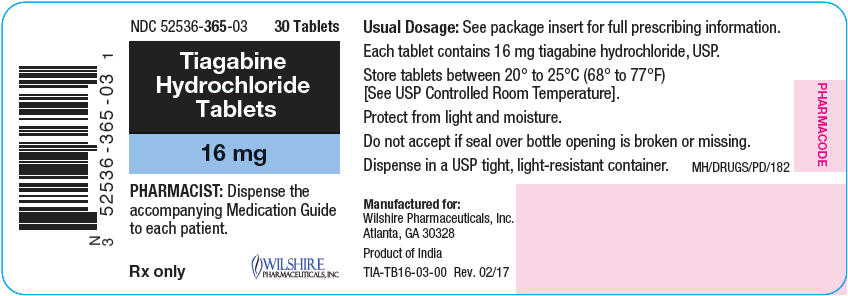

- 16 mg blue, oval, biconvex, film-coated tablets, debossed with 'ω' on one side and '16' on the other side are available in bottles of 30 (NDC: 52536-365-03). Each bottle contains a desiccant canister.

-

ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY

In repeat dose toxicology studies, dogs receiving daily oral doses of 5 mg/kg/day or greater experienced unexpected CNS effects throughout the study. These effects occurred acutely and included marked sedation and apparent visual impairment which was characterized by a lack of awareness of objects, failure to fix on and follow moving objects, and absence of a blink reaction. Plasma exposures (AUCs) at 5 mg/kg/day were equal to those in humans receiving the maximum recommended daily human dose of 56 mg/day. The effects were reversible upon cessation of treatment and were not associated with any observed structural abnormality. The implications of these findings for humans are unknown.

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

Medication Guide

Tiagabine Hydrochloride Tablets

(tye-AG-a-been HYE-droe-KLOR-ide)Read this Medication Guide before you start taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your medical condition or treatment.

What is the most important information I should know about tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

Do not stop taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets without first talking to your healthcare provider.

Stopping tiagabine hydrochloride tablets suddenly can cause serious problems.

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets can cause serious side effects, including:

- 1.

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may cause seizures in people who do not have epilepsy. If you do not have a seizure disorder and you take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, you may have a seizure or seizures that do not stop (status epilepticus). Call your healthcare provider right away if you have a seizure and you are not taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets for epilepsy.

- 2. Like other antiepileptic drugs, tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may cause suicidal thoughts or actions in a very small number of people, about 1 in 500. Call a healthcare provider right away if you have any of these symptoms, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you:

- thoughts about suicide or dying

- attempts to commit suicide

- new or worse depression

- new or worse anxiety

- feeling agitated or restless

- panic attacks

- trouble sleeping (insomnia)

- new or worse irritability

- acting aggressive, being angry, or violent

- acting on dangerous impulses

- an extreme increase in activity and talking (mania)

- other unusual changes in behavior or mood

- 2. Like other antiepileptic drugs, tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may cause suicidal thoughts or actions in a very small number of people, about 1 in 500. Call a healthcare provider right away if you have any of these symptoms, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you:

Suicidal thoughts or actions can be caused by things other than medicines. If you have suicidal thoughts or actions, your healthcare provider may check for other causes.

How can I watch for early symptoms of suicidal thoughts and actions?

- Pay attention to any changes, especially sudden changes, in mood, behaviors, thoughts, or feelings.

- Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider as scheduled.

- Call your healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you are worried about symptoms.

Do not stop tiagabine hydrochloride tablets without first talking to a healthcare provider.

- Stopping tiagabine hydrochloride tablets suddenly can cause serious problems. If you have epilepsy and stop a seizure medicine suddenly, you may have more frequent seizures or seizures that will not stop (status epilepticus).

What are tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets are a prescription medicine used with other medicines to treat partial seizures in adults and children age 12 and older.

Who should not take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

Do not take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets if you are allergic to tiagabine hydrochloride or any of the other ingredients in tiagabine hydrochloride tablets. See the end of this Medication Guide for a complete list of ingredients in tiagabine hydrochloride tablets.

What should I tell my healthcare provider before taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

Before taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, tell your healthcare provider if you:

- have or have had depression, mood problems, or suicidal thoughts or behavior

- have liver problems

- have a history of seizures that do not stop (status epilepticus)

- have any other medical conditions

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. It is not known if tiagabine hydrochloride tablets can harm your unborn baby. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you become pregnant while taking tiagabine hydrochloride. You and your healthcare provider will decide if you should take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets while you are pregnant.

- If you become pregnant while taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, talk to your healthcare provider about registering with the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry. The purpose of this registry is to collect information about the safety of antiepileptic medicines during pregnancy. You can enroll in this registry by calling 1-888-233-2334.

- are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. It is not known if tiagabine hydrochloride passes into breast milk or if it can harm your baby. Talk to your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby if you take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets.

Tell your healthcare provider about all the medicines you take, including prescription and non-prescription medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements. Taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets with certain other medicines can cause side effects or affect how well they work. Do not start or stop other medicines without talking to your healthcare provider.

Know the medicines you take. Keep a list of them and show it to your healthcare provider and pharmacist when you get a new medicine. Always tell your healthcare provider if there are any changes in any other medicines that you take.

How should I take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

- Take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets exactly as your healthcare provider tells you.

- Your healthcare provider may change your dose.

- Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets should be taken with food.

- Do not stop taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets without talking to your healthcare provider. Stopping tiagabine hydrochloride tablets suddenly can increase your chances of having a seizure or cause seizures that will not stop.

- If you miss a dose of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, do not take 2 doses of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets at the same time. Contact your healthcare provider if you miss more than one dose.

If you take too many tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, call your healthcare provider or local Poison Control Center right away.

What should I avoid while taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

- Do not drink alcohol or take other medicines that make you sleepy or dizzy while taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets without first talking to your healthcare provider. Taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets with alcohol or drugs that cause sleepiness or dizziness may make your sleepiness or dizziness worse.

- Do not drive, operate heavy machinery, or do other dangerous activities until you know how tiagabine hydrochloride tablets affect you. Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets can slow your thinking and motor skills.

What are possible side effects of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

See "What is the most important information I should know about tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?"

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may cause other serious side effects including:

- seizures that can happen more often or become worse

- trouble concentrating, problems with speech and language, feeling confused, feeling sleepy and tired, and problems thinking

- weakness all over your body

- eye and vision problems

- serious rash

Call your healthcare provider right away if you have any of the serious side effects listed above.

The most common side effects of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets include:

- dizziness

- lack of energy

- drowsiness

- nausea

- nervousness

- tremor

- stomach pain

- abnormal thinking

- difficulty with concentration or attention

These are not all the possible side effects of tiagabine hydrochloride tablets. For more information, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

How should I store tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

- Store tiagabine hydrochloride tablets between 68°F to 77°F (20°C to 25°C).

- Keep tiagabine hydrochloride tablets out of light.

- Keep tiagabine hydrochloride tablets dry.

Keep tiagabine hydrochloride tablets and all medicines out of the reach of children.

General Information about tiagabine hydrochloride tablets

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use tiagabine hydrochloride tablets for a condition for which they were not prescribed. Do not give tiagabine hydrochloride to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them.

This Medication Guide summarizes the most important information about tiagabine hydrochloride tablets. If you would like more information, talk with your healthcare provider. You can ask your pharmacist or healthcare provider for information about tiagabine hydrochloride tablets that is written for health professionals.

For more information, call 1-877-495-6856.

What are the ingredients in tiagabine hydrochloride tablets?

Active Ingredient: tiagabine hydrochloride

Inactive Ingredients: anhydrous lactose, microcrystalline cellulose, pregelatinized starch, crospovidone, polyethylene glycol 6000, butylated hydroxyanisole, propyl gallate, colloidal silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, stearic acid, hydroxypropyl cellulose, hypromellose and titanium dioxide.

In addition:

- the 2 mg tablets contain FD&C Yellow No. 6

- the 4 mg tablets contain D&C Yellow No.10

- the 12 mg tablets contain D&C Yellow No. 10 and FD&C Blue No. 1

- the 16 mg tablets contain FD&C Blue No. 2

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Rx only

Manufactured for:

Wilshire Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Atlanta, GA 30328Product of India

Rev. 04/2017

TIA-MG-01

- 1.

Tiagabine hydrochloride tablets may cause seizures in people who do not have epilepsy. If you do not have a seizure disorder and you take tiagabine hydrochloride tablets, you may have a seizure or seizures that do not stop (status epilepticus). Call your healthcare provider right away if you have a seizure and you are not taking tiagabine hydrochloride tablets for epilepsy.

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 2 mg Tablet Bottle Label

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 4 mg Tablet Bottle Label

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 12 mg Tablet Bottle Label

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 16 mg Tablet Bottle Label

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

TIAGABINE HYDROCHLORIDE

tiagabine hydrochloride tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 52536-350 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength tiagabine hydrochloride (UNII: DQH6T6D8OY) (tiagabine - UNII:Z80I64HMNP) tiagabine hydrochloride 2 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength anhydrous lactose (UNII: 3SY5LH9PMK) microcrystalline cellulose (UNII: OP1R32D61U) starch, corn (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) CROSPOVIDONE (120 .MU.M) (UNII: 68401960MK) polyethylene glycol 6000 (UNII: 30IQX730WE) butylated hydroxyanisole (UNII: REK4960K2U) propyl gallate (UNII: 8D4SNN7V92) silicon dioxide (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) magnesium stearate (UNII: 70097M6I30) stearic acid (UNII: 4ELV7Z65AP) hydroxypropyl cellulose, unspecified (UNII: 9XZ8H6N6OH) hypromellose, unspecified (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) titanium dioxide (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) FD&C Yellow No. 6 (UNII: H77VEI93A8) Product Characteristics Color ORANGE (orange-peach) Score no score Shape ROUND (biconvex) Size 5mm Flavor Imprint Code w;2 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 52536-350-03 30 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 06/01/2018 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA206857 06/01/2018 TIAGABINE HYDROCHLORIDE