METOPROLOL TARTRATE tablet

Metoprolol Tartrate by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Metoprolol Tartrate by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Med-Health Pharma, LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

Ischemic Heart Disease: Following abrupt cessation of therapy with certain beta-blocking agents, exacerbations of angina pectoris and, in some cases, myocardial infarction have occurred. When discontinuing chronically administered metoprolol, particularly in patients with ischemic heart disease, the dosage should be gradually reduced over a period of 1 to 2 weeks and the patient should be carefully monitored. If angina markedly worsens or acute coronary insufficiency develops, metoprolol administration should be reinstated promptly, at least temporarily, and other measures appropriate for the management of unstable angina should be taken. Patients should be warned against interruption or discontinuation of therapy without the physician’s advice. Because coronary artery disease is common and may be unrecognized, it may be prudent not to discontinue metoprolol therapy abruptly even in patients treated only for hypertension.

-

DESCRIPTION

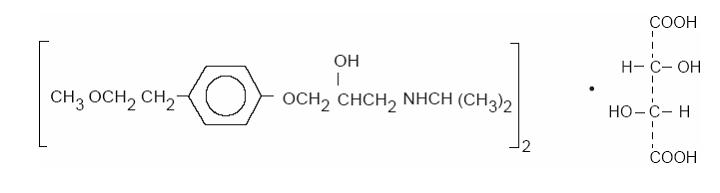

Metoprolol tartrate, USP is a selective beta1-adrenoreceptor blocking agent, available as 25, 50 and 100 mg tablets for oral administration. Metoprolol tartrate is (±)-1-(isopropylamino)-3-[ p-(2-methoxyethyl) phenoxy]-2-propanol (2:1) dextro-tartrate salt, and its structural formula is:

(C15H25NO3)2 C4H6O6

Metoprolol tartrate is a white, practically odorless, crystalline powder with a molecular weight of 684.82. It is very soluble in water; freely soluble in methylene chloride, in chloroform, and in alcohol; slightly soluble in acetone; and insoluble in ether.

Inactive Ingredients. Tablets contain colloidal silicon dioxide, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate, povidone, sodium starch glycolate, talc and titanium dioxide.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Metoprolol tartrate is a beta-adrenergic receptor blocking agent. In vitro and in vivo animal studies have shown that it has a preferential effect on beta1 adrenoreceptors, chiefly located in cardiac muscle. This preferential effect is not absolute, however, and at higher doses, metoprolol also inhibits beta2 adrenoreceptors, chiefly located in the bronchial and vascular musculature.

Clinical pharmacology studies have confirmed the beta-blocking activity of metoprolol in man, as shown by (1) reduction in heart rate and cardiac output at rest and upon exercise, (2) reduction of systolic blood pressure upon exercise, (3) inhibition of isoproterenol-induced tachycardia, and (4) reduction of reflex orthostatic tachycardia.

Relative beta1 selectivity has been confirmed by the following: (1) In normal subjects, metoprolol is unable to reverse the beta2-mediated vasodilating effects of epinephrine. This contrasts with the effect of nonselective (beta1 plus beta2) beta blockers, which completely reverse the vasodilating effects of epinephrine. (2) In asthmatic patients, metoprolol reduces FEV1 and FVC significantly less than a nonselective beta blocker, propranolol, at equivalent beta1-receptor blocking doses.

Metoprolol has no intrinsic sympathomimetic activity, and membrane-stabilizing activity is detectable only at doses much greater than required for beta blockade. Metoprolol crosses the blood-brain barrier and has been reported in the CSF in a concentration 78% of the simultaneous plasma concentration. Animal and human experiments indicate that metoprolol slows the sinus rate and decreases AV nodal conduction.

In controlled clinical studies, metoprolol tartrate has been shown to be an effective antihypertensive agent when used alone or as concomitant therapy with thiazide-type diuretics, at dosages of 100 to 450 mg daily. In controlled, comparative, clinical studies, metoprolol has been shown to be as effective an antihypertensive agent as propranolol, methyldopa, and thiazide-type diuretics, and to be equally effective in supine and standing positions.

The mechanism of the antihypertensive effects of beta-blocking agents has not been elucidated. However, several possible mechanisms have been proposed: (1) competitive antagonism of catecholamines at peripheral (especially cardiac) adrenergic neuron sites, leading to decreased cardiac output; (2) a central effect leading to reduced sympathetic outflow to the periphery; and (3) suppression of renin activity.

By blocking catecholamine-induced increases in heart rate, in velocity and extent of myocardial contraction, and in blood pressure, metoprolol reduces the oxygen requirements of the heart at any given level of effort, thus making it useful in the long-term management of angina pectoris. However, in patients with heart failure, beta-adrenergic blockade may increase oxygen requirements by increasing left ventricular fiber length and end-diastolic pressure.

Although beta-adrenergic receptor blockade is useful in the treatment of angina and hypertension, there are situations in which sympathetic stimulation is vital. In patients with severely damaged hearts, adequate ventricular function may depend on sympathetic drive. In the presence of AV block, beta blockade may prevent the necessary facilitating effect of sympathetic activity on conduction. Beta2-adrenergic blockade results in passive bronchial constriction by interfering with endogenous adrenergic bronchodilator activity in patients subject to bronchospasm and may also interfere with exogenous bronchodilators in such patients.

In controlled clinical trials, metoprolol tartrate, administered two or four times daily, has been shown to be an effective antianginal agent, reducing the number of angina attacks and increasing exercise tolerance. The dosage used in these studies ranged from 100 to 400 mg daily. A controlled, comparative, clinical trial showed that metoprolol was indistinguishable from propranolol in the treatment of angina pectoris.

In a large (1,395 patients randomized), double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study, metoprolol was shown to reduce 3-month mortality by 36% in patients with suspected or definite myocardial infarction.

Patients were randomized and treated as soon as possible after their arrival in the hospital, once their clinical condition had stabilized and their hemodynamic status had been carefully evaluated. Subjects were ineligible if they had hypotension, bradycardia, peripheral signs of shock, and/or more than minimal basal rales as signs of congestive heart failure. Initial treatment consisted of intravenous followed by oral administration of metoprolol tartrate or placebo, given in a coronary care or comparable unit. Oral maintenance therapy with metoprolol or placebo was then continued for 3 months. After this double-blind period, all patients were given metoprolol and followed up to 1 year.

The median delay from the onset of symptoms to the initiation of therapy was 8 hours in both the metoprolol- and placebo-treatment groups. Among patients treated with metoprolol, there were comparable reductions in 3-month mortality for those treated early (≤8 hours) and those in whom treatment was started later. Significant reductions in the incidence of ventricular fibrillation and in chest pain following initial intravenous therapy were also observed with metoprolol and were independent of the interval between onset of symptoms and initiation of therapy.

The precise mechanism of action of metoprolol in patients with suspected or definite myocardial infarction is not known.

In this study, patients treated with metoprolol received the drug both very early (intravenously) and during a subsequent 3-month period, while placebo patients received no beta-blocker treatment for this period. The study thus was able to show a benefit from the overall metoprolol regimen but cannot separate the benefit of very early intravenous treatment from the benefit of later beta-blocker therapy. Nonetheless, because the overall regimen showed a clear beneficial effect on survival without evidence of an early adverse effect on survival, one acceptable dosage regimen is the precise regimen used in the trial. Because the specific benefit of very early treatment remains to be defined however, it is also reasonable to administer the drug orally to patients at a later time as is recommended for certain other beta blockers.

Pharmacokinetics

In man, absorption of metoprolol is rapid and complete. Plasma levels following oral administration, however, approximate 50% of levels following intravenous administration, indicating about 50% first-pass metabolism.

Plasma levels achieved are highly variable after oral administration. Only a small fraction of the drug (about 12%) is bound to human serum albumin. Metoprolol is a racemic mixture of R- and S- enantiomers. Less than 5% of an oral dose of metoprolol is recovered unchanged in the urine; the rest is excreted by the kidneys as metabolites that appear to have no clinical significance. The systemic availability and half-life of metoprolol in patients with renal failure do not differ to a clinically significant degree from those in normal subjects. Consequently, no reduction in dosage is usually needed in patients with chronic renal failure.

Metoprolol is extensively metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system in the liver. The oxidative metabolism of metoprolol is under genetic control with a major contribution of the polymorphic cytochrome P450 isoform 2D6 (CYP2D6). There are marked ethnic differences in the prevalence of the poor metabolizers (PM) phenotype. Approximately 7% of Caucasians and less than 1% Asian are poor metabolizers.

Poor CYP2D6 metabolizers exhibit several-fold higher plasma concentrations of metoprolol than extensive metabolizers with normal CYP2D6 activity. The elimination half-life of metoprolol is about 7.5 hours in poor metabolizers and 2.8 hours in extensive metabolizers. However, the CYP2D6 dependent metabolism of metoprolol seems to have little or no effect on safety or tolerability of the drug. None of the metabolites of metoprolol contribute significantly to its beta-blocking effect.

Significant beta-blocking effect (as measured by reduction of exercise heart rate) occurs within 1 hour after oral administration, and its duration is dose-related. For example, a 50% reduction of the maximum registered effect after single oral doses of 20, 50, and 100 mg occurred at 3.3, 5.0, and 6.4 hours, respectively, in normal subjects. After repeated oral dosages of 100 mg twice daily, a significant reduction in exercise systolic blood pressure was evident at 12 hours.

Following intravenous administration of metoprolol, the urinary recovery of unchanged drug is approximately 10%. When the drug was infused over a 10-minute period, in normal volunteers, maximum beta blockade was achieved at approximately 20 minutes. Doses of 5 mg and 15 mg yielded a maximal reduction in exercise-induced heart rate of approximately 10% and 15%, respectively. The effect on exercise heart rate decreased linearly with time at the same rate for both doses, and disappeared at approximately 5 hours and 8 hours for the 5-mg and 15-mg doses, respectively.

Equivalent maximal beta-blocking effect is achieved with oral and intravenous doses in the ratio of approximately 2.5:1.

There is a linear relationship between the log of plasma levels and reduction of exercise heart rate. However, antihypertensive activity does not appear to be related to plasma levels. Because of variable plasma levels attained with a given dose and lack of a consistent relationship of antihypertensive activity to dose, selection of proper dosage requires individual titration.

In several studies of patients with acute myocardial infarction, intravenous followed by oral administration of metoprolol caused a reduction in heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and cardiac output. Stroke volume, diastolic blood pressure, and pulmonary artery end diastolic pressure remained unchanged.

In patients with angina pectoris, plasma concentration measured at 1 hour is linearly related to the oral dose within the range of 50 to 400 mg. Exercise heart rate and systolic blood pressure are reduced in relation to the logarithm of the oral dose of metoprolol. The increase in exercise capacity and the reduction in left ventricular ischemia are also significantly related to the logarithm of the oral dose.

In elderly subjects with clinically normal renal and hepatic function, there are no significant differences in metoprolol pharmacokinetics compared to young subjects.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Hypertension

Metoprolol tartrate tablets are indicated for the treatment of hypertension. They may be used alone or in combination with other antihypertensive agents.

Angina Pectoris

Metoprolol tartrate tablets are indicated in the long-term treatment of angina pectoris.

Myocardial Infarction

Metoprolol tartrate injection and tablets are indicated in the treatment of hemodynamically stable patients with definite or suspected acute myocardial infarction to reduce cardiovascular mortality. Treatment with intravenous metoprolol tartrate can be initiated as soon as the patient’s clinical condition allows (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, CONTRAINDICATIONS, and WARNINGS). Alternatively, treatment can begin within 3 to 10 days of the acute event (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Hypertension and Angina

Metoprolol tartrate is contraindicated in sinus bradycardia, heart block greater than first degree, cardiogenic shock, and overt cardiac failure (see WARNINGS).

Hypersensitivity to metoprolol and related derivatives, or to any of the excipients; hypersensitivity to other beta-blockers (cross sensitivity between beta-blockers can occur).

Sick-sinus syndrome.

Severe peripheral arterial circulatory disorders.

Myocardial Infarction

Metoprolol is contraindicated in patients with a heart rate < 45 beats/min; second- and third-degree heart block; significant first-degree heart block (P-R interval ≥0.24 sec); systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg; or moderate-to-severe cardiac failure (see WARNINGS).

-

WARNINGS

Hypertension and Angina

Cardiac Failure

Sympathetic stimulation is a vital component supporting circulatory function in congestive heart failure, and beta blockade carries the potential hazard of further depressing myocardial contractility and precipitating more severe failure. In hypertensive and angina patients who have congestive heart failure controlled by digitalis and diuretics, metoprolol should be administered cautiously.

In Patients Without a History of Cardiac Failure

Continued depression of the myocardium with beta-blocking agents over a period of time can, in some cases, lead to cardiac failure. At the first sign or symptom of impending cardiac failure, patients should be fully digitalized and/or given a diuretic. The response should be observed closely. If cardiac failure continues, despite adequate digitalization and diuretic therapy, metoprolol should be withdrawn.

Bronchospastic Diseases

PATIENTS WITH BRONCHOSPASTIC DISEASES SHOULD, IN GENERAL, NOT RECEIVE BETA BLOCKERS, including Metoprolol tartrate. Because of its relative beta1 selectivity, however, metoprolol may be used with caution in patients with bronchospastic disease who do not respond to, or cannot tolerate, other antihypertensive treatment. Since beta1 selectivity is not absolute, a beta2-stimulating agent should be administered concomitantly, and the lowest possible dose of metoprolol tartrate should be used. In these circumstances it would be prudent initially to administer metoprolol in smaller doses three times daily, instead of larger doses two times daily, to avoid the higher plasma levels associated with the longer dosing interval (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Major Surgery

Chronically administered beta-blocking therapy should not be routinely withdrawn prior to major surgery; however, the impaired ability of the heart to respond to reflex adrenergic stimuli may augment the risks of general anesthesia and surgical procedures.

Diabetes and Hypoglycemia

Metoprolol should be used with caution in diabetic patients if a beta-blocking agent is required. Beta blockers may mask tachycardia occurring with hypoglycemia, but other manifestations such as dizziness and sweating may not be significantly affected.

Pheochromocytoma

If metoprolol is used in the setting of pheochromocytoma, it should be given in combination with an alpha blocker, and only after the alpha blocker has been initiated. Administration of beta blockers alone in the setting of pheochromocytoma has been associated with a paradoxical increase in blood pressure due to the attenuation of beta-mediated vasodilatation in skeletal muscle.

Myocardial Infarction

Cardiac Failure

Sympathetic stimulation is a vital component supporting circulatory function, and beta blockade carries the potential hazard of depressing myocardial contractility and precipitating or exacerbating minimal cardiac failure.

During treatment with metoprolol, the hemodynamic status of the patient should be carefully monitored. If heart failure occurs or persists despite appropriate treatment, metoprolol should be discontinued.

Bradycardia

Metoprolol produces a decrease in sinus heart rate in most patients; this decrease is greatest among patients with high initial heart rates and least among patients with low initial heart rates. Acute myocardial infarction (particularly inferior infarction) may in itself produce significant lowering of the sinus rate. If the sinus rate decreases to < 40 beats/min, particularly if associated with evidence of lowered cardiac output, atropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg) should be administered intravenously. If treatment with atropine is not successful, metoprolol should be discontinued, and cautious administration of isoproterenol or installation of a cardiac pacemaker should be considered.

AV Block

Metoprolol slows AV conduction and may produce significant first- (P-R intervals ≥0.26 sec), second-, or third-degree heart block. Acute myocardial infarction also produces heart block.

If heart block occurs, metoprolol should be discontinued and atropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg) should be administered intravenously. If treatment with atropine is not successful, cautious administration of isoproterenol or installation of a cardiac pacemaker should be considered.

Hypotension

If hypotension (systolic blood pressure ≤90 mmHg) occurs, metoprolol should be discontinued, and the hemodynamic status of the patient and the extent of myocardial damage carefully assessed. Invasive monitoring of central venous, pulmonary capillary wedge, and arterial pressures may be required. Appropriate therapy with fluids, positive inotropic agents, balloon counterpulsation, or other treatment modalities should be instituted. If hypotension is associated with sinus bradycardia or AV block, treatment should be directed at reversing these (see above).

Bronchospastic Diseases

PATIENTS WITH BRONCHOSPASTIC DISEASES SHOULD, IN GENERAL, NOT RECEIVE BETA BLOCKERS, including Metoprolol tartrate. Because of its relative beta1 selectivity, metoprolol may be used with extreme caution in patients with bronchospastic disease. Because it is unknown to what extent beta2-stimulating agents may exacerbate myocardial ischemia and the extent of infarction, these agents should not be used prophylactically. If bronchospasm not related to congestive heart failure occurs, metoprolol should be discontinued. A theophylline derivative or a beta2 agonist may be administered cautiously, depending on the clinical condition of the patient. Both theophylline derivatives and beta2 agonists may produce serious cardiac arrhythmias.

-

PRECAUTIONS

Information for Patients

Patients should be advised to take metoprolol regularly and continuously, as directed, with or immediately following meals. If a dose should be missed, the patient should take only the next scheduled dose (without doubling it). Patients should not discontinue metoprolol without consulting the physician.

Patients should be advised (1) to avoid operating automobiles and machinery or engaging in other tasks requiring alertness until the patient’s response to therapy with metoprolol has been determined; (2) to contact the physician if any difficulty in breathing occurs; (3) to inform the physician or dentist before any type of surgery that he or she is taking metoprolol.

Drug Interactions

Catecholamine-depleting drugs (e.g., reserpine) may have an additive effect when given with beta-blocking agents. Patients treated with metoprolol plus a catecholamine depletor should therefore be closely observed for evidence of hypotension or marked bradycardia, which may produce vertigo, syncope, or postural hypotension.

Both digitalis glycosides and beta-blockers slow atrioventricular conduction and decrease heart rate. Concomitant use can increase the risk of bradycardia.

Risk of Anaphylactic Reaction

While taking beta-blockers, patients with a history of severe anaphylactic reaction to a variety of allergens may be more reactive to repeated challenge, either accidental, diagnostic, or therapeutic. Such patients may be unresponsive to the usual doses of epinephrine used to treat allergic reaction.

General Anesthetics

Some inhalation anesthetics may enhance the cardiodepressant effect of beta-blockers (see WARNINGS, Major Surgery)

CYP2D6 Inhibitors

Potent inhibitors of the CYP2D6 enzyme may increase the plasma concentration of metoprolol. Strong inhibition of CYP2D6 would mimic the pharmacokinetics of CYP2D6 poor metabolizer (see Pharmacokinetics section). Caution should therefore be exercised when co-administering potent CYP2D6 inhibitors with metoprolol. Known clinically significant potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 are antidepressants such as fluoxetine, paroxetine or bupropion, antipsychotics such as thioridazine, antiarrhythmics such as quinidine or propafenone, antiretrovirals such as ritonavir, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine or quinidine, antifungals such as terbinafine and medications for stomach ulcers such as cimetidine.

Clonidine

If a patient is treated with clonidine and metoprolol concurrently, and clonidine treatment is to be discontinued, metoprolol should be stopped several days before clonidine is withdrawn.

Rebound hypertension that can follow withdrawal of clonidine may be increased in patients receiving concurrent beta-blocker treatment.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Long-term studies in animals have been conducted to evaluate carcinogenic potential. In a 2-year study in rats at three oral dosage levels of up to 800 mg/kg per day, there was no increase in the development of spontaneously occurring benign or malignant neoplasms of any type. The only histologic changes that appeared to be drug related were an increased incidence of generally mild focal accumulation of foamy macrophages in pulmonary alveoli and a slight increase in biliary hyperplasia. In a 21-month study in Swiss albino mice at three oral dosage levels of up to 750 mg/kg per day, benign lung tumors (small adenomas) occurred more frequently in female mice receiving the highest dose than in untreated control animals. There was no increase in malignant or total (benign plus malignant) lung tumors,or in the overall incidence of tumors or malignant tumors. This 21-month study was repeated in CD-1 mice, and no statistically or biologically significant differences were observed between treated and control mice of either sex for any type of tumor.

All mutagenicity tests performed (a dominant lethal study in mice, chromosome studies in somatic cells, a Salmonella/mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test, and a nucleus anomaly test in somatic interphase nuclei) were negative.

No evidence of impaired fertility due to metoprolol was observed in a study performed in rats at doses up to 55.5 times the maximum daily human dose of 450 mg.

Pregnancy Category C

Metoprolol has been shown to increase postimplantation loss and decrease neonatal survival in rats at doses up to 55.5 times the maximum daily human dose of 450 mg. Distribution studies in mice confirm exposure of the fetus when metoprolol is administered to the pregnant animal. These studies have revealed no evidence of impaired fertility or teratogenicity. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, this drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

Nursing Mothers

Metoprolol is excreted in breast milk in a very small quantity. An infant consuming 1 liter of breast milk daily would receive a dose of less than 1 mg of the drug. Caution should be exercised when metoprolol is administered to a nursing woman.

Geriatric Use

Clinical trials of metoprolol tartrate USP, in hypertension did not include sufficient numbers of elderly patients to determine whether patients over 65 years of age differ from younger subjects in their response to metoprolol tartrate. Other reported clinical experience in elderly hypertensive patients has not identified any difference in response from younger patients.

In worldwide clinical trials of metoprolol tartrate in myocardial infarction, where approximately 478 patients were over 65 years of age (0 over 75 years of age), no-age related differences in safety and effectiveness were found. Other reported clinical experience in myocardial infarction has not identified differences in response between the elderly and younger patients. However, greater sensitivity of some elderly individuals taking metoprolol tartrate cannot be categorically ruled out. Therefore, in general, it is recommended that dosing proceed with caution in this population.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Hypertension and Angina

Most adverse effects have been mild and transient.

Central Nervous System: Tiredness and dizziness have occurred in about 10 of 100 patients. Depression has been reported in about 5 of 100 patients. Mental confusion and short-term memory loss have been reported. Headache, nightmares, and insomnia have also been reported.

Cardiovascular: Shortness of breath and bradycardia have occurred in approximately 3 of 100 patients. Cold extremities; arterial insufficiency, usually of the Raynaud type; palpitations; congestive heart failure; peripheral edema; and hypotension have been reported in about 1 of 100 patients. Gangrene in patients with pre-existing severe peripheral circulatory disorders has also been reported very rarely. (see CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS, and PRECAUTIONS.)

Respiratory: Wheezing (bronchospasm) and dyspnea have been reported in about 1 of 100 patients (see WARNINGS). Rhinitis has also been reported.

Gastrointestinal: Diarrhea has occurred in about 5 of 100 patients. Nausea, dry mouth, gastric pain, constipation, flatulence, and heartburn have been reported in about 1 of 100 patients. Vomiting was a common occurrence. Post-marketing experience reveals very rare reports of hepatitis, jaundice and non-specific hepatic dysfunction. Isolated cases of transaminase, alkaline phosphatase and lactic dehydrogenase elevations have also been reported.

Hypersensitive Reactions: Pruritus or rash have occurred in about 5 of 100 patients. Very rarely, photosensitivity and worsening of psoriasis has been reported.

Miscellaneous: Peyronie’s disease has been reported in fewer than 1 of 100,000 patients. Musculoskeletal pain, blurred vision, and tinnitus have also been reported.

There have been rare reports of reversible alopecia, agranulocytosis, and dry eyes. Discontinuation of the drug should be considered if any such reaction is not otherwise explicable. There have been very rare reports of weight gain, arthritis, and retroperitoneal fibrosis (relationship to metoprolol has not been definitely established).

The oculomucocutaneous syndrome associated with the beta blocker practolol has not been reported with metoprolol.

Myocardial Infarction

Central Nervous System: Tiredness has been reported in about 1 of 100 patients. Vertigo, sleep disturbances, hallucinations, headache, dizziness, visual disturbances, confusion, and reduced libido have also been reported, but a drug relationship is not clear.

Cardiovascular: In the randomized comparison of metoprolol and placebo described in the CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY section, the following adverse reactions were reported:metoprolol Placebo Hypotension

(systolic BP < 90 mmHg)27.4% 23.2% Bradycardia

(heart rate < 40 beats/min)15.9% 6.7% Second- or

third-degree heart block4.7% 4.7% First-degree

heart block (P-R ≥0.26 sec)5.3% 1.9% Heart failure 27.5% 29.6% Respiratory: Dyspnea of pulmonary origin has been reported in fewer than 1 of 100 patients.

Gastrointestinal: Nausea and abdominal pain have been reported in fewer than 1 of 100 patients.

Dermatologic: Rash and worsened psoriasis have been reported, but a drug relationship is not clear.

Miscellaneous: Unstable diabetes and claudication have been reported, but a drug relationship is not clear.

Potential Adverse Reactions

A variety of adverse reactions not listed above have been reported with other beta-adrenergic blocking agents and should be considered potential adverse reactions to metoprolol.

Central Nervous System: Reversible mental depression progressing to catatonia; an acute reversible syndrome characterized by disorientation for time and place, short-term memory loss, emotional lability, slightly clouded sensorium, and decreased performance on neuropsychometrics.

Cardiovascular: Intensification of AV block (see CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Hematologic: Agranulocytosis, nonthrombocytopenic purpura, thrombocytopenic purpura.

Hypersensitive Reactions: Fever combined with aching and sore throat, laryngospasm, and respiratory distress.

Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been reported during postapproval use of Metoprolol Tartrate: confusional state, an increase in blood triglycerides and a decrease in High Density Lipoprotein (HDL). Because these reports are from a population of uncertain size and are subject to confounding factors, it is not possible to reliably estimate their frequency.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Acute Toxicity

Several cases of overdosage have been reported, some leading to death.

Oral LD50’s (mg/kg): mice, 1158 to 2460; rats, 3090 to 4670.

Signs and Symptoms

Potential signs and symptoms associated with overdosage with metoprolol are bradycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm, and cardiac failure.

Treatment

There is no specific antidote.

In general, patients with acute or recent myocardial infarction may be more hemodynamically unstable than other patients and should be treated accordingly (see WARNINGS, Myocardial Infarction).

On the basis of the pharmacologic actions of metoprolol, the following general measures should be employed:

Elimination of the Drug: Gastric lavage should be performed.

Bradycardia: Atropine should be administered. If there is no response to vagal blockade, isoproterenol should be administered cautiously.

Hypotension: A vasopressor should be administered, e.g., levarterenol or dopamine.

Bronchospasm: A beta2 -stimulating agent and/or a theophylline derivative should be administered.

Cardiac Failure: A digitalis glycoside and diuretic should be administered. In shock resulting from inadequate cardiac contractility, administration of dobutamine, isoproterenol, or glucagon may be considered. -

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Hypertension

The dosage of metoprolol tartrate tablets should be individualized. Metoprolol tartrate tablets should be taken with or immediately following meals.

The usual initial dosage of Metoprolol tartrate tablets is 100 mg daily in single or divided doses, whether used alone or added to a diuretic. The dosage may be increased at weekly (or longer) intervals until optimum blood pressure reduction is achieved. In general, the maximum effect of any given dosage level will be apparent after 1 week of therapy. The effective dosage range of Metoprolol tartrate tablets is 100 to 450 mg per day. Dosages above 450 mg per day have not been studied. While once-daily dosing is effective and can maintain a reduction in blood pressure throughout the day, lower doses (especially 100 mg) may not maintain a full effect at the end of the 24-hour period, and larger or more frequent daily doses may be required. This can be evaluated by measuring blood pressure near the end of the dosing interval to determine whether satisfactory control is being maintained throughout the day. Beta1 selectivity diminishes as the dose of metoprolol is increased.

Angina Pectoris

The dosage of metoprolol tartrate tablets should be individualized. Metoprolol tartrate tablets should be taken with or immediately following meals.

The usual initial dosage of Metoprolol tartrate tablets is 100 mg daily, given in two divided doses. The dosage may be gradually increased at weekly intervals until optimum clinical response has been obtained or there is pronounced slowing of the heart rate. The effective dosage range of Metoprolol tartrate tablets is 100 to 400 mg per day. Dosages above 400 mg per day have not been studied. If treatment is to be discontinued, the dosage should be reduced gradually over a period of 1 to 2 weeks (see WARNINGS).

Myocardial Infarction

Early Treatment

During the early phase of definite or suspected acute myocardial infarction, treatment with metoprolol tartrate can be initiated as soon as possible after the patient’s arrival in the hospital. Such treatment should be initiated in a coronary care or similar unit immediately after the patient’s hemodynamic condition has stabilized.

Treatment in this early phase should begin with the intravenous administration of three bolus injections of 5 mg of metoprolol tartrate each; the injections should be given at approximately 2-minute intervals. During the intravenous administration of metoprolol, blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiogram should be carefully monitored.

In patients who tolerate the full intravenous dose (15 mg), metoprolol tartrate tablets, 50 mg every 6 hours, should be initiated 15 minutes after the last intravenous dose and continued for 48 hours. Thereafter, patients should receive a maintenance dosage of 100 mg twice daily (see Late Treatment below).

Patients who appear not to tolerate the full intravenous dose should be started on metoprolol tartrate tablets either 25 mg or 50 mg every 6 hours (depending on the degree of intolerance) 15 minutes after the last intravenous dose or as soon as their clinical condition allows. In patients with severe intolerance, treatment with metoprolol should be discontinued (see WARNINGS).

Late Treatment

Patients with contraindications to treatment during the early phase of suspected or definite myocardial infarction, patients who appear not to tolerate the full early treatment, and patients in whom the physician wishes to delay therapy for any other reason should be started on metoprolol tartrate tablets, 100 mg twice daily, as soon as their clinical condition allows. Therapy should be continued for at least 3 months. Although the efficacy of metoprolol beyond 3 months has not been conclusively established, data from studies with other beta blockers suggest that treatment should be continued for 1 to 3 years.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Metoprolol Tartrate Tablets USP, 50 mg - Round, white film coated tablets with “477” debossed on one side and scored on the other side

Bottles of 30 NDC: 51138-106-30

Metoprolol Tartrate Tablets USP, 50 mg - capsule-shaped, biconvex, white, scored (debossed 166)

Bottles of 30 NDC: 51138-107-30

Metoprolol Tartrate Tablets USP, 100 mg - round-shaped, film coated, white colored tablets debossed with ‘162’ on one side and ‘scored’ on the other side.

Bottles of 30 NDC: 51138-108-30

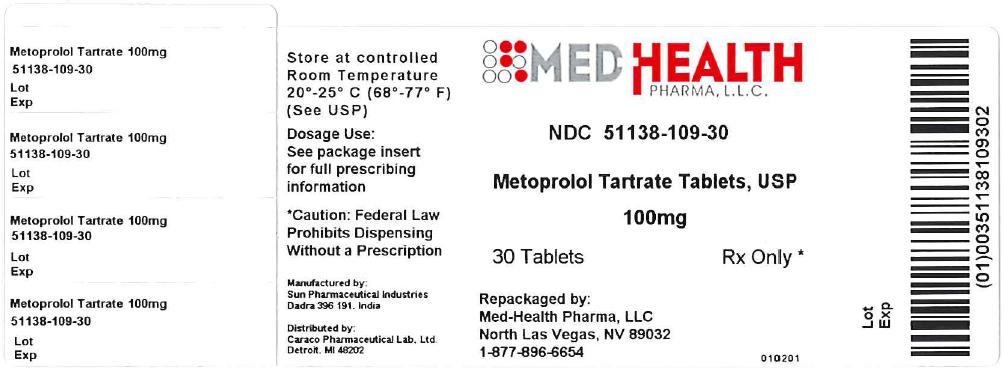

Metoprolol Tartrate Tablets USP, 100 mg - capsule-shaped, biconvex, white, scored (debossed 167)

Bottles of 30 NDC: 51138-109-30

Samples, when available, are identified by the word SAMPLE appearing on each bottle.

Store at 20°-25°C (68°-77°F); excursions permitted to 15°-30°C (59°-86°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Dispense in tight, light-resistant container (USP). Protect from Moisture.To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Med-Health Pharma, LLC at 1-877-896-6654 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch

Manufactured by:

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries

Dadra 396 191, IndiaDistributed by:

Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd.

1150 Elijah McCoy Drive C.S. No.: 5094T84

Detroit, MI 48202 Iss.: 04/11Repackaged By:

Med-Health Pharma, LLC

North Las Vegas, NV 89032

SP-60035 Rev02

-

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

Metroprolol Tartrate Tablets, 50mg

30 Round Tablets NDC: 51138-106-30

Metroprolol Tartrate Tablets, 50mg

30 Tablets NDC: 51138-107-30

Metroprolol Tartrate Tablets, 100mg

30 Round Tablets NDC: 51138-108-30

Metroprolol Tartrate Tablets, 100mg

30 Tablets NDC: 51138-109-30

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

METOPROLOL TARTRATE

metoprolol tartrate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 51138-106(NDC:57664-477) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength METOPROLOL TARTRATE (UNII: W5S57Y3A5L) (METOPROLOL - UNII:GEB06NHM23) METOPROLOL TARTRATE 50 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) POLYSORBATE 20 (UNII: 7T1F30V5YH) POVIDONE (UNII: FZ989GH94E) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (WHITE) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND Size 8mm Flavor Imprint Code 477 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 51138-106-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA074644 01/15/2011 METOPROLOL TARTRATE

metoprolol tartrate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 51138-107(NDC:57664-166) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength METOPROLOL TARTRATE (UNII: W5S57Y3A5L) (METOPROLOL - UNII:GEB06NHM23) METOPROLOL TARTRATE 50 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) POLYSORBATE 20 (UNII: 7T1F30V5YH) POVIDONE (UNII: FZ989GH94E) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (WHITE) Score 2 pieces Shape CAPSULE Size 11mm Flavor Imprint Code 166 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 51138-107-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA074644 01/15/2011 METOPROLOL TARTRATE

metoprolol tartrate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 51138-108(NDC:57664-162) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength METOPROLOL TARTRATE (UNII: W5S57Y3A5L) (METOPROLOL - UNII:GEB06NHM23) METOPROLOL TARTRATE 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) POLYSORBATE 20 (UNII: 7T1F30V5YH) POVIDONE (UNII: FZ989GH94E) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (WHITE) Score 2 pieces Shape ROUND Size 14mm Flavor Imprint Code 162 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 51138-108-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA074644 01/15/2011 METOPROLOL TARTRATE

metoprolol tartrate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 51138-109(NDC:57664-167) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength METOPROLOL TARTRATE (UNII: W5S57Y3A5L) (METOPROLOL - UNII:GEB06NHM23) METOPROLOL TARTRATE 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) POLYSORBATE 20 (UNII: 7T1F30V5YH) POVIDONE (UNII: FZ989GH94E) SODIUM STARCH GLYCOLATE TYPE A POTATO (UNII: 5856J3G2A2) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) Product Characteristics Color WHITE (WHITE) Score 2 pieces Shape CAPSULE Size 14mm Flavor Imprint Code 167 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 51138-109-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA074644 01/15/2011 Labeler - Med-Health Pharma, LLC (962603812) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Med-Health Pharma, LLC 962603812 repack

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.