RANITIDINE- ranitidine hydrochloride tablet

RANITIDINE by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

RANITIDINE by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by WOCKHARDT LIMITED. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

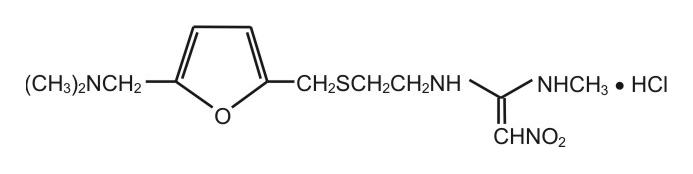

The active ingredient in ranitidine tablets 150 mg and 300 mg is ranitidine hydrochloride (HCl), USP, a histamine H2-receptor antagonist. Chemically it is N[2-[[[5- [(dimethylamino)methyl]-2-furanyl]methyl]thio]ethyl]-N’-methyl-2-nitro-1,1-ethenediamine, HCl. It has the following structure:

The empirical formula is C13H22N4O3SHCl, representing a molecular weight of 350.87.

Ranitidine HCl is a white to pale yellow, crystalline practically odorless powder, very soluble in water, sparingly soluble in alcohol.

Each ranitidine tablet 150 mg for oral administration contains 168 mg of ranitidine HCl equivalent to 150 mg of ranitidine. Each tablet also contains the inactive ingredients microcrystalline cellulose, croscarmellose sodium, magnesium stearate, colloidal silicon dioxide, hypromellose, titanium dioxide, diethyl phthalate, FD&C yellow # 6 and iron oxide red.

Each Ranitidine Tablet 300 mg for oral administration contains 336 mg of ranitidine HCl equivalent to 300 mg of ranitidine. Each tablet also contains the inactive ingredients microcrystalline cellulose, croscarmellose sodium, magnesium stearate, colloidal silicon dioxide, hypromellose, titanium dioxide, and diethyl phthalate. -

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Ranitidine is a competitive, reversible inhibitor of the action of histamine at the histamine H2-receptors, including receptors on the gastric cells. Ranitidine does not lower serum Ca++ in hypercalcemic states. Ranitidine is not an anticholinergic agent.

Pharmacokinetics:

Absorption: Ranitidine is 50% absorbed after oral administration, compared to an intravenous (IV) injection with mean peak levels of 440 to 545 ng/mL occurring 2 to 3 hours after a 150-mg dose. Absorption is not significantly impaired by the administration of food or antacids. Propantheline slightly delays and increases peak blood levels of ranitidine, probably by delaying gastric emptying and transit time. In one study, simultaneous administration of high-potency antacid (150 mmol) in fasting subjects has been reported to decrease the absorption of ranitidine.

Distribution: The volume of distribution is about 1.4 L/kg. Serum protein binding averages 15%.

Metabolism: In humans, the N-oxide is the principal metabolite in the urine; however, this amounts to <4% of the dose. Other metabolites are the S-oxide (1%) and the desmethyl ranitidine (1%). The remainder of the administered dose is found in the stool. Studies in patients with hepatic dysfunction (compensated cirrhosis) indicate that there are minor, but clinically insignificant, alterations in ranitidine half-life, distribution, clearance, and bioavailability.

Excretion: The principal route of excretion is the urine, with approximately 30% of the orally administered dose collected in the urine as unchanged drug in 24 hours. Renal clearance is about 410 mL/min, indicating active tubular excretion. The elimination half-life is 2.5 to 3 hours. Four patients with clinically significant renal function impairment (creatinine clearance 25 to 35 mL/min) administered 50 mg of ranitidine intravenously had an average plasma half-life of 4.8 hours, a ranitidine clearance of 29 mL/min, and a volume of distribution of 1.76 L/kg. In general, these parameters appear to be altered in proportion to creatinine clearance (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Geriatrics: The plasma half-life is prolonged and total clearance is reduced in the elderly population due to a decrease in renal function. The elimination half-life is 3 to 4 hours. Peak levels average 526 ng/mL following a 150-mg twice daily dose and occur in about 3 hours (see PRECAUTIONS: Geriatric Use and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION: Dosage Adjustment for Patients With Impaired Renal Function).

Pediatrics: There are no significant differences in the pharmacokinetic parameter values for ranitidine in pediatric patients (from 1 month up to 16 years of age) and healthy adults when correction is made for body weight. The average bioavailability of ranitidine given orally to pediatric patients is 48% which is comparable to the bioavailability of ranitidine in the adult population. All other pharmacokinetic parameter values (t1/2, Vd, and CL) are similar to those observed with intravenous ranitidine use in pediatric patients. Estimates of Cmax and Tmax are displayed in Table 1.

Plasma clearance measured in 2 neonatal patients (less than 1 month of age) was considerably lower (3 mL/min/kg) than children or adults and is likely due to reduced renal function observed in this population (see PRECAUTIONS: Pediatric Use and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION: Pediatric Use).Table 1. Ranitidine Pharmacokinetics in Pediatric Patients Following Oral Dosing Population (age) n Dosage Form

(dose)Cmax

(ng/mL)Tmax

(hours)Gastric or duodenal ulcer

(3.5 to 16 years)12 Tablets

(1 to 2 mg/kg)54 to 492 2.0 Otherwise healthy requiring ranitidine

(0.7 to 14 years, Single dose)10 Syrup

(2 mg/kg)244 1.61 Otherwise healthy requiring ranitidine

(0.7 to 14 years, Multiple dose)10 Syrup

(2 mg/kg)320 1.66

Pharmacodynamics: Serum concentrations necessary to inhibit 50% of stimulated gastric acid secretion are estimated to be 36 to 94 ng/mL. Following a single oral dose of 150 mg, serum concentrations of ranitidine are in this range up to 12 hours. However, blood levels bear no consistent relationship to dose or degree of acid inhibition.

Antisecretory Activity: 1. Effects on Acid Secretion: Ranitidine inhibits both daytime and nocturnal basal gastric acid secretions as well as gastric acid secretion stimulated by food, betazole, and pentagastrin, as shown in Table 2.

It appears that basal-, nocturnal-, and betazole-stimulated secretions are most sensitive to inhibition by ranitidine, responding almost completely to doses of 100 mg or less, while pentagastrin- and food-stimulated secretions are more difficult to suppress.Table 2. Effect of Oral Ranitidine on Gastric Acid Secretion Time After

Dose, hours% Inhibition of Gastric Acid Output by Dose, mg 75-80 100 150 200 Basal Up to 4 99 95 Nocturnal Up to 13 95 96 92 Betazole Up to 3 97 99 Pentagastin Up to 5 58 72 72 80 Meal Up to 3 73 79 95

2. Effects on Other Gastrointestinal Secretions:

Pepsin: Oral ranitidine does not affect pepsin secretion. Total pepsin output is reduced in proportion to the decrease in volume of gastric juice.

Intrinsic Factor: Oral ranitidine has no significant effect on pentagastrin-stimulated intrinsic factor secretion.

Serum Gastrin: Ranitidine has little or no effect on fasting or postprandial serum gastrin.

Other Pharmacologic Actions:

- Gastric bacterial flora—increase in nitrate-reducing organisms, significance not known.

- Prolactin levels—no effect in recommended oral or IV dosage, but small, transient, dose-related increases in serum prolactin have been reported after IV bolus injections of 100 mg or more.

- Other pituitary hormones—no effect on serum gonadotropins, TSH, or GH. Possible impairment of vasopressin release.

- No change in cortisol, aldosterone, androgen, or estrogen levels.

- No antiandrogenic action.

- No effect on count, motility, or morphology of sperm.

Pediatrics: Oral doses of 6 to 10 mg/kg/day in 2 or 3 divided doses maintain gastric pH>4 throughout most of the dosing interval.

Clinical Trials: Active Duodenal Ulcer: In a multicenter, double-blind, controlled, US study of endoscopically diagnosed duodenal ulcers, earlier healing was seen in the patients treated with ranitidine as shown in Table 3.

* All patients were permitted antacids as needed for relief of pain.Table 3. Duodenal Ulcer Patient Healing Rates Ranitidine* Placebo* Number

EnteredHealed /

EvaluableNumber

EnteredHealed /

EvaluableOutpatients 195

69/182

(38%) †188

31/164

(19%)Week 2 Week 4 137/187

(73%) †76/168

(45%)

†P<0.0001.

In these studies, patients treated with ranitidine reported a reduction in both daytime and nocturnal pain, and they also consumed less antacid than the placebo-treated patients.

Foreign studies have shown that patients heal equally well with 150 mg twice daily and 300 mg at bedtime (85% versus 84%, respectively) during a usual 4-week course of therapy. If patients require extended therapy of 8 weeks, the healing rate may be higher for 150 mg twice daily as compared to 300 mg at bedtime (92% versus 87%, respectively).Table 4. Mean Daily Doses of Antacid Ulcer Healed Ulcer Not Healed Ranitidine 0.06 0.71 Placebo 0.71 1.43

Studies have been limited to short-term treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. Patients whose ulcers healed during therapy had recurrences of ulcers at the usual rates.

Maintenance Therapy in Duodenal Ulcer: Ranitidine has been found to be effective as maintenance therapy for patients following healing of acute duodenal ulcers. In 2 independent, double-blind, multicenter, controlled trials, the number of duodenal ulcers observed was significantly less in patients treated with ranitidine (150 mg at bedtime) than in patients treated with placebo over a 12-month period.

% = Life table estimate.Table 5. Duodenal Ulcer Prevalence Double-Blind, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Trials Multicenter

TrialDrug Duodenal Ulcer Prevalence No. Of Patients 0-4

Months0-8

Months0-12

MonthsUSA RAN 20%* 24%* 35%* 138 PLC 44% 54% 59% 139 Foreign RAN 12%* 21%* 28%* 174 PLC 56% 64% 68% 165

* = P<0.05 (ranitidine versus comparator).

RAN = ranitidine.

PLC = placebo.

As with other H2-antagonists, the factors responsible for the significant reduction in the prevalence of duodenal ulcers include prevention of recurrence of ulcers, more rapid healing of ulcers that may occur during maintenance therapy, or both.

Gastric Ulcer: In a multicenter, double-blind, controlled, US study of endoscopically diagnosed gastric ulcers, earlier healing was seen in the patients treated with ranitidine as shown in Table 6.

* All patients were permitted antacids as needed for relief of pain.Table 6. Gastric Ulcer Patient Healing Rates Ranitidine* Placebo* Number

EnteredHealed /

EvaluableNumber

EnteredHealed /

EvaluableOutpatients 92

16/83

(19%)94

10/83

(12%)Week 2 Week 6 50/73

(68%)†35/69

(51%)

†P = 0.009.

In this multicenter trial, significantly more patients treated with ranitidine became pain free during therapy.

Maintenance of Healing of Gastric Ulcers: In 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-month trials conducted in patients whose gastric ulcers had been previously healed, ranitidine 150 mg at bedtime was significantly more effective than placebo in maintaining healing of gastric ulcers.

Pathological Hypersecretory Conditions (such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome): Ranitidine inhibits gastric acid secretion and reduces occurrence of diarrhea, anorexia, and pain in patients with pathological hypersecretion associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, systemic mastocytosis, and other pathological hypersecretory conditions (e.g., postoperative, "short-gut" syndrome, idiopathic). Use of ranitidine was followed by healing of ulcers in 8 of 19 (42%) patients who were intractable to previous therapy.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): In 2 multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trials performed in the United States and Europe, ranitidine 150 mg twice daily was more effective than placebo for the relief of heartburn and other symptoms associated with GERD. Ranitidine-treated patients consumed significantly less antacid than did placebo-treated patients.

The US trial indicated that ranitidine 150 mg twice daily significantly reduced the frequency of heartburn attacks and severity of heartburn pain within 1 to 2 weeks after starting therapy. The improvement was maintained throughout the 6-week trial period. Moreover, patient response rates demonstrated that the effect on heartburn extends through both the day and night time periods.

In 2 additional US multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2-week trials, ranitidine 150 mg twice daily was shown to provide relief of heartburn pain within 24 hours of initiating therapy and a reduction in the frequency of severity of heartburn.

Erosive Esophagitis: In 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trials performed in the United States, ranitidine 150 mg 4 times daily was significantly more effective than placebo in healing endoscopically diagnosed erosive esophagitis and in relieving associated heartburn. The erosive esophagitis healing rates were as follows:

* All patients were permitted antacids as needed for relief of pain.Table 7. Erosive Esophagitis Patient Healing Rates Healed / Evaluable Placebo*

n=229Ranitidine HCl

150 mg 4 times daily*

n=215Week 4 43/198 (22%) 96/206 (47%) † Week 8 63/176 (36%) 142/200 (71%) † Week 12 92/159 (58%) 162/192 (84%) †

†P<0.001 versus placebo.

No additional benefit in healing of esophagitis or in relief of heartburn was seen with a ranitidine dose of 300 mg 4 times daily.

Maintenance of Healing of Erosive Esophagitis: In 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 48-week trials conducted in patients whose erosive esophagitis had been previously healed, ranitidine 150 mg twice daily was significantly more effective than placebo in maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. -

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Ranitidine Tablets are indicated in:

- Short-term treatment of active duodenal ulcer. Most patients heal within 4 weeks. Studies available to date have not assessed the safety of ranitidine in uncomplicated duodenal ulcer for periods of more than 8 weeks.

- Maintenance therapy for duodenal ulcer patients at reduced dosage after healing of acute ulcers. No placebo-controlled comparative studies have been carried out for periods of longer than 1 year.

- The treatment of pathological hypersecretory conditions (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and systemic mastocytosis).

- Short-term treatment of active, benign gastric ulcer. Most patients heal within 6 weeks and the usefulness of further treatment has not been demonstrated. Studies available to date have not assessed the safety of ranitidine in uncomplicated, benign gastric ulcer for periods of more than 6 weeks.

- Maintenance therapy for gastric ulcer patients at reduced dosage after healing of acute ulcers. Placebo-controlled studies have been carried out for 1 year.

- Treatment of GERD. Symptomatic relief commonly occurs within 24 hours after starting therapy with ranitidine 150 mg twice daily.

- Treatment of endoscopically diagnosed erosive esophagitis. Symptomatic relief of heartburn commonly occurs within 24 hours of therapy initiation with ranitidine 150 mg 4 times daily.

- Maintenance of healing of erosive esophagitis. Placebo-controlled trials have been carried out for 48 weeks.

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

PRECAUTIONS

General:

- Symptomatic response to therapy with ranitidine does not preclude the presence of gastric malignancy.

- Since ranitidine is excreted primarily by the kidney, dosage should be adjusted in patients with impaired renal function (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Caution should be observed in patients with hepatic dysfunction since ranitidine is metabolized in the liver.

- Rare reports suggest that ranitidine may precipitate acute porphyric attacks in patients with acute porphyria. Ranitidine should therefore be avoided in patients with a history of acute porphyria.

Drug Interactions: Ranitidine has been reported to affect the bioavailability of other drugs through several different mechanisms such as competition for renal tubular secretion, alteration of gastric pH, and inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes.

Procainamide: Ranitidine, a substrate of the renal organic cation transport system, may affect the clearance of other drugs eliminated by this route. High doses of ranitidine (e.g., such as those used in the treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) have been shown to reduce the renal excretion of procainamide and N-acetylprocainamide resulting in increased plasma levels of these drugs. Although this interaction is unlikely to be clinically relevant at usual ranitidine doses, it may be prudent to monitor for procainamide toxicity when administered with oral ranitidine at a dose exceeding 300 mg per day.

Warfarin: There have been reports of altered prothrombin time among patients on concomitant warfarin and ranitidine therapy. Due to the narrow therapeutic index, close monitoring of increased or decreased prothrombin time is recommended during concurrent treatment with ranitidine.

Ranitidine may alter the absorption of drugs in which gastric pH is an important determinant of bioavailability. This can result in either an increase in absorption (e.g., triazolam, midazolam, glipizide) or a decrease in absorption (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, delavirdine, gefitinib). Appropriate clinical monitoring is recommended.

Atazanavir: Atazanavir absorption may be impaired based on known interactions with other agents that increase gastric pH. Use with caution. See atazanavir label for specific recommendations.

Delavirdine: Delavirdine absorption may be impaired based on known interactions with other agents that increase gastric pH. Chronic use of H2-receptor antagonists with delavirdine is not recommended.

Gefitinib: Gefitinib exposure was reduced by 44% with the coadministration of ranitidine and sodium bicarbonate (dosed to maintain gastric pH above 5.0). Use with caution.

Glipizide: In diabetic patients, glipizide exposure was increased by 34% following a single 150-mg dose of oral ranitidine. Use appropriate clinical monitoring when initiating or discontinuing ranitidine.

Ketoconazole: Oral ketoconazole exposure was reduced by up to 95% when oral ranitidine was coadministered in a regimen to maintain a gastric pH of 6 or above. The degree of interaction with usual dose of ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) is unknown.

Midazolam: Oral midazolam exposure in 5 healthy volunteers was increased by up to 65% when administered with oral ranitidine at a dose of 150 mg twice daily. However, in another interaction study in 8 volunteers receiving IV midazolam, a 300 mg oral dose of ranitidine increased midazolam exposure by about 9%. Monitor patients for excessive or prolonged sedation when ranitidine is coadministered with oral midazolam.

Triazolam: Triazolam exposure in healthy volunteers was increased by approximately 30% when administered with oral ranitidine at a dose of 150 mg twice daily. Monitor patients for excessive or prolonged sedation.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility: There was no indication of tumorigenic or carcinogenic effects in life-span studies in mice and rats at dosages up to 2,000 mg/kg/day.

Ranitidine was not mutagenic in standard bacterial tests (Salmonella, Escherichia coli) for mutagenicity at concentrations up to the maximum recommended for these assays.

In a dominant lethal assay, a single oral dose of 1,000 mg/kg to male rats was without effect on the outcome of 2 matings per week for the next 9 weeks.

Pregnancy: Teratogenic Effects: Pregnancy Category B. Reproduction studies have been performed in rats and rabbits at doses up to 160 times the human dose and have revealed no evidence of impaired fertility or harm to the fetus due to ranitidine. There are, however, no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, this drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

Nursing Mothers: Ranitidine is secreted in human milk. Caution should be exercised when ranitidine is administered to a nursing mother.

Pediatric Use: The safety and effectiveness of ranitidine have been established in the age-group of 1 month to 16 years for the treatment of duodenal and gastric ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease and erosive esophagitis, and the maintenance of healed duodenal and gastric ulcer. Use of ranitidine in this age-group is supported by adequate and well-controlled studies in adults, as well as additional pharmacokinetic data in pediatric patients and an analysis of the published literature (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Pediatrics and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION: Pediatric Use).

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients for the treatment of pathological hypersecretory conditions or the maintenance of healing of erosive esophagitis have not been established.

Safety and effectiveness in neonates (less than 1 month of age) have not been established (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Pediatrics).

Geriatric Use: Of the total number of subjects enrolled in US and foreign controlled clinical trials of oral formulations of ranitidine, for which there were subgroup analyses, 4,197 were 65 and over, while 899 were 75 and over. No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out.

This drug is known to be substantially excreted by the kidney and the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, caution should be exercised in dose selection, and it may be useful to monitor renal function (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Pharmacokinetics: Geriatrics and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION: Dosage Adjustment for Patients With Impaired Renal Function).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following have been reported as events in clinical trials or in the routine management of patients treated with ranitidine. The relationship to therapy with ranitidine has been unclear in many cases. Headache, sometimes severe, seems to be related to administration of ranitidine.

Central Nervous System: Rarely, malaise, dizziness, somnolence, insomnia, and vertigo. Rare cases of reversible mental confusion, agitation, depression, and hallucinations have been reported, predominantly in severely ill elderly patients. Rare cases of reversible blurred vision suggestive of a change in accommodation have been reported. Rare reports of reversible involuntary motor disturbances have been received.

Cardiovascular: As with other H2-blockers, rare reports of arrhythmias such as tachycardia, bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and premature ventricular beats.

Gastrointestinal: Constipation, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, abdominal discomfort/ pain, and rare reports of pancreatitis.

Hepatic: There have been occasional reports of hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed hepatitis, with or without jaundice. In such circumstances, ranitidine should be immediately discontinued. These events are usually reversible, but in rare circumstances death has occurred. Rare cases of hepatic failure have also been reported. In normal volunteers, SGPT values were increased to at least twice the pretreatment levels in 6 of 12 subjects receiving 100 mg intravenously 4 times daily for 7 days, and in 4 of 24 subjects receiving 50 mg intravenously 4 times daily for 5 days.

Musculoskeletal: Rare reports of arthralgias and myalgias.

Hematologic: Blood count changes (leukopenia, granulocytopenia, and thrombocytopenia) have occurred in a few patients. These were usually reversible. Rare cases of agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, sometimes with marrow hypoplasia, and aplastic anemia and exceedingly rare cases of acquired immune hemolytic anemia have been reported.

Endocrine: Controlled studies in animals and man have shown no stimulation of any pituitary hormone by ranitidine and no antiandrogenic activity, and cimetidine-induced gynecomastia and impotence in hypersecretory patients have resolved when ranitidine has been substituted. However, occasional cases of impotence and loss of libido have been reported in male patients receiving ranitidine, but the incidence did not differ from that in the general population. Rare cases of breast symptoms and conditions, including galactorrhea and gynecomastia, have been reported in both males and females.

Integumentary: Rash, including rare cases of erythema multiforme. Rare cases of alopecia and vasculitis.

Respiratory: A large epidemiological study suggested an increased risk of developing pneumonia in current users of histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) compared to patients who had stopped H2RA treatment, with an observed adjusted relative risk of 1.63 (95% CI, 1.07- 2.48). However, a causal relationship between use of H2RAs and pneumonia has not been established.

Other: Rare cases of hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., bronchospasm, fever, rash, eosinophilia), anaphylaxis, angioneurotic edema, acute interstitial nephritis, and small increases in serum creatinine. -

OVERDOSAGE

There has been limited experience with overdosage. Reported acute ingestions of up to 18 g orally have been associated with transient adverse effects similar to those encountered in normal clinical experience (see ADVERSE REACTIONS). In addition, abnormalities of gait and hypotension have been reported.

When overdosage occurs, the usual measures to remove unabsorbed material from the gastrointestinal tract, clinical monitoring, and supportive therapy should be employed.

Studies in dogs receiving dosages of ranitidine in excess of 225 mg/kg/day have shown muscular tremors, vomiting, and rapid respiration. Single oral doses of 1,000 mg/kg in mice and rats were not lethal. Intravenous LD50 values in mice and rats were 77 and 83 mg/kg, respectively. -

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Active Duodenal Ulcer: The current recommended adult oral dosage of ranitidine for duodenal ulcer is 150 mg twice daily. An alternative dosage of 300 mg once daily after the evening meal or at bedtime can be used for patients in whom dosing convenience is important. The advantages of one treatment regimen compared to the other in a particular patient population have yet to be demonstrated (see Clinical Trials: Active Duodenal Ulcer). Smaller doses have been shown to be equally effective in inhibiting gastric acid secretion in US studies, and several foreign trials have shown that 100 mg twice daily is as effective as the 150-mg dose.

Antacid should be given as needed for relief of pain (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Pharmacokinetics).

Maintenance of Healing of Duodenal Ulcers: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg at bedtime.

Pathological Hypersecretory Conditions (such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome): The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg twice daily. In some patients it may be necessary to administer ranitidine 150-mg doses more frequently. Dosages should be adjusted to individual patient needs, and should continue as long as clinically indicated. Dosages up to 6 g/day have been employed in patients with severe disease.

Benign Gastric Ulcer: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg twice daily.

Maintenance of Healing of Gastric Ulcers: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg at bedtime.

GERD: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg twice daily.

Erosive Esophagitis: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg 4 times daily.

Maintenance of Healing of Erosive Esophagitis: The current recommended adult oral dosage is 150 mg twice daily.

Pediatric Use: The safety and effectiveness of ranitidine have been established in the age-group of 1 month to 16 years. There is insufficient information about the pharmacokinetics of ranitidine in neonatal patients (less than 1 month of age) to make dosing recommendations.

The following 3 subsections provide dosing information for each of the pediatric indications.

Treatment of Duodenal and Gastric Ulcers: The recommended oral dose for the treatment of active duodenal and gastric ulcers is 2 to 4 mg/kg twice daily to a maximum of 300 mg/day. This recommendation is derived from adult clinical studies and pharmacokinetic data in pediatric patients.

Maintenance of Healing of Duodenal and Gastric Ulcers: The recommended oral dose for the maintenance of healing of duodenal and gastric ulcers is 2 to 4 mg/kg once daily to a maximum of 150 mg/day. This recommendation is derived from adult clinical studies and pharmacokinetic data in pediatric patients.

Treatment of GERD and Erosive Esophagitis: Although limited data exist for these conditions in pediatric patients, published literature supports a dosage of 5 to 10 mg/kg/day, usually given as 2 divided doses.

Dosage Adjustment for Patients With Impaired Renal Function: On the basis of experience with a group of subjects with severely impaired renal function treated with ranitidine, the recommended dosage in patients with a creatinine clearance <50 mL/min is 150 mg or 10 mL of syrup (2 teaspoonfuls of syrup equivalent to 150 mg of ranitidine) every 24 hours. Should the patient's condition require, the frequency of dosing may be increased to every 12 hours or even further with caution. Hemodialysis reduces the level of circulating ranitidine. Ideally, the dosing schedule should be adjusted so that the timing of a scheduled dose coincides with the end of hemodialysis.

Elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, therefore caution should be exercised in dose selection, and it may be useful to monitor renal function (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Pharmacokinetics: Geriatrics and PRECAUTIONS: Geriatric Use). -

HOW SUPPLIED

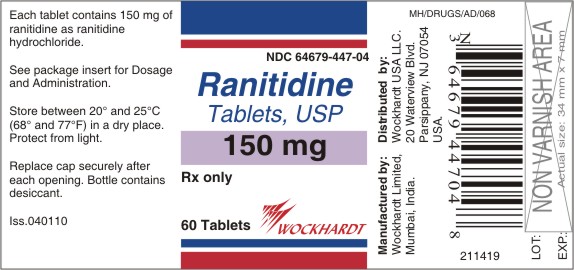

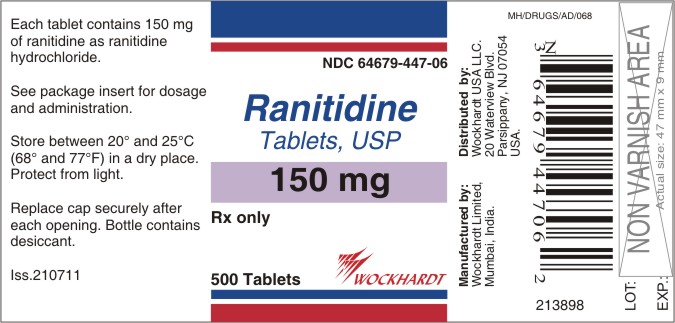

Ranitidine Tablets USP 150 mg (ranitidine HCl equivalent to 150 mg of ranitidine) are orange colored, film-coated, irregular hexagonal-shaped tablets debossed with "W" on one side and plain on other side. 447

They are available in following packs.

PACKS NDC NUMBER

10 Tablets 64679-447-01

60 Tablets 64679-447-04

100 Tablets 64679-447-02

10 X 10’s Blister Pack 64679-447-03

500 Tablets 64679-447-06

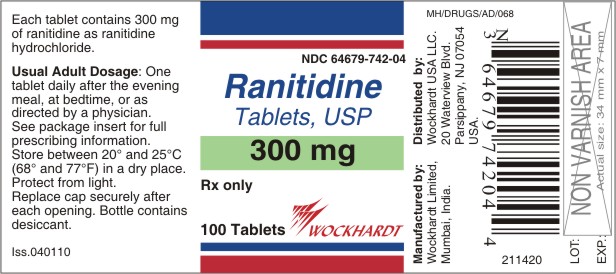

Ranitidine Tablets USP 300 mg (ranitidine HCl equivalent to 300 mg of ranitidine) are white to off white, film-coated, capsule-shaped tablets debossed with "W742" on one side and plain on other side.

They are available in following packs.

PACKS NDC NUMBER

30 Tablets 64679-742-01

100 Tablets 64679-742-04

250 Tablets 64679-742-02

10 X 10’s Blister Pack 64679-742-03

Store between 20° and 25°C (68°and 77°F) in a dry place. Protect from light. Replace cap securely after each opening.

Bottle contains desiccant.

Rx only

MULTISTIX is a registered trademark of Bayer Healthcare LLC.

Manufactured By:

Wockhardt Limited

Mumbai, India.

Distributed By:

Wockhardt USA LLC.

20 Waterview Blvd.

Parsippany, NJ 07054

USA.

Iss.210711

- PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

RANITIDINE

ranitidine hydrochloride tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 55648-447 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength RANITIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE (UNII: BK76465IHM) (RANITIDINE - UNII:884KT10YB7) RANITIDINE 150 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) CROSCARMELLOSE SODIUM (UNII: M28OL1HH48) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) COLLOIDAL SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) DIETHYL PHTHALATE (UNII: UF064M00AF) FD&C YELLOW NO. 6 (UNII: H77VEI93A8) FERRIC OXIDE RED (UNII: 1K09F3G675) Product Characteristics Color orange (Orange) Score no score Shape HEXAGON (6 sided) (irregular hexagonal-shaped) Size 10mm Flavor Imprint Code W;447 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 55648-447-01 10 in 1 BOTTLE 2 NDC: 55648-447-04 60 in 1 BOTTLE 3 NDC: 55648-447-02 100 in 1 BOTTLE 4 NDC: 55648-447-03 10 in 1 CARTON 4 10 in 1 BLISTER PACK 5 NDC: 55648-447-05 15000 in 1 DRUM 6 NDC: 55648-447-06 500 in 1 BOTTLE 7 NDC: 55648-447-07 6000 in 1 DRUM Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA078701 12/11/2009 RANITIDINE

ranitidine hydrochloride tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 55648-742 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength RANITIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE (UNII: BK76465IHM) (RANITIDINE - UNII:884KT10YB7) RANITIDINE 300 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength CELLULOSE, MICROCRYSTALLINE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) CROSCARMELLOSE SODIUM (UNII: M28OL1HH48) MAGNESIUM STEARATE (UNII: 70097M6I30) COLLOIDAL SILICON DIOXIDE (UNII: ETJ7Z6XBU4) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) DIETHYL PHTHALATE (UNII: UF064M00AF) Product Characteristics Color white (white to off white) Score no score Shape CAPSULE (capsule-shaped) Size 16mm Flavor Imprint Code W742 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 55648-742-01 30 in 1 BOTTLE 2 NDC: 55648-742-04 100 in 1 BOTTLE 3 NDC: 55648-742-02 250 in 1 BOTTLE 4 NDC: 55648-742-03 10 in 1 CARTON 4 10 in 1 BLISTER PACK 5 NDC: 55648-742-09 7500 in 1 DRUM 6 NDC: 55648-742-08 3000 in 1 DRUM Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA078701 12/11/2009 Labeler - WOCKHARDT LIMITED (650069115)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.