INSPRA- eplerenone tablet

Inspra by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Inspra by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Rebel Distributors Corp. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use INSPRA safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for INSPRA.

INSPRA (eplerenone) tablet for oral use

Initial U.S. Approval: 2002INDICATIONS AND USAGE

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

CHF Post-MI: Initiate treatment with 25 mg once daily. Titrate to maximum of 50 mg once daily within 4 weeks, as tolerated. Dose adjustments may be required based on potassium levels. (2.1)

Hypertension: 50 mg once daily, alone or combined with other antihypertensive agents. For inadequate response, increase to 50 mg twice daily. Higher dosages are not recommended. (2.2)

For all patients:

Measure serum potassium before starting INSPRA and periodically thereafter. (2.3)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Tablets: 25 mg, 50 mg (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Hyperkalemia: Patients with decreased renal function and diabetics with proteinuria are at increased risk. Proper patient selection and monitoring and avoiding certain concomitant medications can minimize the risk. (5.1)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

CHF Post-MI: Most common adverse reactions (>2% and more frequent than with placebo): hyperkalemia and increased creatinine. (6.1)

Hypertension: Most common adverse reactions (≥2% and more frequent than with placebo): dizziness, diarrhea, coughing, fatigue and flu-like symptoms. (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Pfizer Inc. at 1-800-438-1985 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch

DRUG INTERACTIONS

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION.

Revised: 8/2009

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Patient Selection Considerations

1.2 Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

1.3 Hypertension

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

2.2 Hypertension

2.3 Recommended Monitoring

2.4 Dose Modifications for Specific Populations

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Hyperkalemia

5.2 Impaired Hepatic Function

5.3 Impaired Renal Function

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Clinical Laboratory Test Findings

6.3 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 CYP3A4 Inhibitors

7.2 ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists

7.3 Lithium

7.4 Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

14.2 Hypertension

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Patient Selection Considerations

Serum potassium levels should be measured before initiating INSPRA therapy, and INSPRA should not be prescribed if serum potassium is >5.5 mEq/L. [See CONTRAINDICATIONS (4)].

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

Treatment should be initiated at 25 mg once daily and titrated to the recommended dose of 50 mg once daily, preferably within 4 weeks as tolerated by the patient. INSPRA may be administered with or without food.

Once treatment with INSPRA has begun, adjust the dose based on the serum potassium level as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Dose Adjustment in Congestive Heart Failure Post-MI Serum Potassium

(mEq/L)Action Dose Adjustment < 5.0 Increase 25 mg every other day to 25 mg once daily

25 mg once daily to 50 mg once daily5.0–5.4 Maintain No adjustment 5.5–5.9 Decrease 50 mg once daily to 25 mg once daily

25 mg once daily to 25 mg every other day

25 mg every other day to withhold≥ 6.0 Withhold Restart at 25 mg every other day when potassium levels fall to <5.5 mEq/L 2.2 Hypertension

The recommended starting dose of INSPRA is 50 mg administered once daily. The full therapeutic effect of INSPRA is apparent within 4 weeks. For patients with an inadequate blood pressure response to 50 mg once daily the dosage of INSPRA should be increased to 50 mg twice daily. Higher dosages of INSPRA are not recommended because they have no greater effect on blood pressure than 100 mg and are associated with an increased risk of hyperkalemia. [See CLINICAL STUDIES (14.2).]

2.3 Recommended Monitoring

Serum potassium should be measured before initiating INSPRA therapy, within the first week, and at one month after the start of treatment or dose adjustment. Serum potassium should be assessed periodically thereafter. Patient characteristics and serum potassium levels may indicate that additional monitoring is appropriate. [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1), ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.2).] In the EPHESUS study [See CLINICAL STUDIES (14.1)], the majority of hyperkalemia was observed within the first three months after randomization.

In all patients taking INSPRA who start taking a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor, check serum potassium and serum creatinine in 3–7 days.

2.4 Dose Modifications for Specific Populations

For hypertensive patients receiving moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., erythromycin, saquinavir, verapamil, and fluconazole), the starting dose of INSPRA should be reduced to 25 mg once daily. [See DRUG INTERACTIONS (7.1).]

No adjustment of the starting dose is recommended for the elderly or for patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment. [See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

- 3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

-

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

For All Patients

INSPRA is contraindicated in all patients with:

- serum potassium >5.5 mEq/L at initiation,

- creatinine clearance ≤30 mL/min, or

- concomitant administration of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, itraconazole, nefazodone, troleandomycin, clarithromycin, ritonavir, and nelfinavir). [See DRUG INTERACTIONS (7.1), CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

For Patients Treated for Hypertension

INSPRA is contraindicated for the treatment of hypertension in patients with:

- type 2 diabetes with microalbuminuria,

- serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL in males or >1.8 mg/dL in females,

- creatinine clearance <50 mL/min, or

- concomitant administration of potassium supplements or potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., amiloride, spironolactone, or triamterene). [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1), ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.2), DRUG INTERACTIONS (7), and CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Hyperkalemia

Minimize the risk of hyperkalemia with proper patient selection and monitoring, and avoidance of certain concomitant medications [See CONTRAINDICATIONS (4), ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.2), and DRUG INTERACTIONS (7)]. Monitor patients for the development of hyperkalemia until the effect of INSPRA is established. Patients who develop hyperkalemia (>5.5 mEq/L) may continue INSPRA therapy with proper dose adjustment. Dose reduction decreases potassium levels. [See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (2.1).]

The rates of hyperkalemia increase with declining renal function. [See ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.2).] Patients with hypertension who have serum creatinine levels >2.0 mg/dL (males) or >1.8 mg/dL (females) or creatinine clearance ≤50 mL/min should not be treated with INSPRA. [See CONTRAINDICTIONS (4).] Patients with CHF post-MI who have serum creatinine levels >2.0 mg/dL (males) or >1.8 mg/dL (females) or creatinine clearance ≤50mL/min should be treated with INSPRA with caution.

Diabetic patients with CHF post-MI should also be treated with caution, especially those with proteinuria. The subset of patients in the EPHESUS study with both diabetes and proteinuria on the baseline urinalysis had increased rates of hyperkalemia compared to patients with either diabetes or proteinuria. [See ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.2).]

5.2 Impaired Hepatic Function

Mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment did not increase the incidence of hyperkalemia. In 16 subjects with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment who received 400 mg of eplerenone, no elevations of serum potassium above 5.5 mEq/L were observed. The mean increase in serum potassium was 0.12 mEq/L in patients with hepatic impairment and 0.13 mEq/L in normal controls. The use of INSPRA in patients with severe hepatic impairment has not been evaluated. [See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

5.3 Impaired Renal Function

Patients with decreased renal function are at increased risk of hyperkalemia. [See CONTRAINDICATIONS (4),WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1), ADVERSE REACTIONS (6.1).]

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions are discussed in greater detail in other sections of the labeling:

- Hyperkalemia [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1)]

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

In EPHESUS, safety was evaluated in 3307 patients treated with INSPRA and 3301 placebo-treated patients. The overall incidence of adverse events reported with INSPRA (78.9%) was similar to placebo (79.5%). Adverse events occurred at a similar rate regardless of age, gender, or race. Patients discontinued treatment due to an adverse event at similar rates in either treatment group (4.4% INSPRA vs. 4.3% placebo), with the most common reasons for discontinuation being hyperkalemia, myocardial infarction, and abnormal renal function.

Adverse reactions that occurred more frequently in patients treated with INSPRA than placebo were hyperkalemia (3.4% vs. 2.0%) and increased creatinine (2.4% vs. 1.5%). Discontinuations due to hyperkalemia or abnormal renal function were less than 1.0% in both groups. Hypokalemia occurred less frequently in patients treated with INSPRA (0.6% vs. 1.6%).

The rates of sex hormone-related adverse events are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Rates of Sex Hormone-Related Adverse Events in EPHESUS Rates in Males Rates in Females Gynecomastia Mastodynia Either Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding INSPRA 0.4% 0.1% 0.5% 0.4% Placebo 0.5% 0.1% 0.6% 0.4% Hypertension

INSPRA has been evaluated for safety in 3091 patients treated for hypertension. A total of 690 patients were treated for over 6 months and 106 patients were treated for over 1 year.

In placebo-controlled studies, the overall rates of adverse events were 47% with INSPRA and 45% with placebo. Adverse events occurred at a similar rate regardless of age, gender, or race. Therapy was discontinued due to an adverse event in 3% of patients treated with INSPRA and 3% of patients given placebo. The most common reasons for discontinuation of INSPRA were headache, dizziness, angina pectoris/myocardial infarction, and increased GGT. The adverse events that were reported at a rate of at least 1% of patients and at a higher rate in patients treated with INSPRA in daily doses of 25 to 400 mg versus placebo are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Rates (%) of Adverse Events Occurring in Placebo-Controlled Hypertension Studies in ≥1% of Patients Treated with INSPRA (25 to 400 mg) and at a More Frequent Rate than in Placebo-Treated Patients INSPRA

(n=945)Placebo

(n=372)Note: Adverse events that are too general to be informative or are very common in the treated population are excluded. Metabolic Hypercholesterolemia 1 0 Hypertriglyceridemia 1 0 Digestive Diarrhea 2 1 Abdominal pain 1 0 Urinary Albuminuria 1 0 Respiratory Coughing 2 1 Central/Peripheral Nervous System Dizziness 3 2 Body as a Whole Fatigue 2 1 Influenza-like symptoms 2 1 Gynecomastia and abnormal vaginal bleeding were reported with INSPRA but not with placebo. The rates of these sex hormone-related adverse events are shown in Table 4. The rates increased slightly with increasing duration of therapy. In females, abnormal vaginal bleeding was also reported in 0.8% of patients on antihypertensive medications (other than spironolactone) in active control arms of the studies with INSPRA.

Table 4. Rates of Sex Hormone-Related Adverse Events with INSPRA in Hypertension Clinical Studies Rates in Males Rates in Females Gynecomastia Mastodynia Either Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding All controlled studies 0.5% 0.8% 1.0% 0.6% Controlled studies lasting ≥ 6 months 0.7% 1.3% 1.6% 0.8% Open-label, long-term study 1.0% 0.3% 1.0% 2.1% 6.2 Clinical Laboratory Test Findings

Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

Creatinine: Increases of more than 0.5 mg/dL were reported for 6.5% of patients administered INSPRA and for 4.9% of placebo-treated patients.

Potassium: In EPHESUS [see CLINICAL STUDIES (14.1)], the frequencies of patients with changes in potassium (<3.5 mEq/L or >5.5 mEq/L or ≥6.0 mEq/L) receiving INSPRA compared with placebo are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5. Hypokalemia (<3.5 mEq/L) or Hyperkalemia (>5.5 or ≥6.0 mEq/L) in EPHESUS Potassium (mEq/L) INSPRA

(N=3251)

n (%)Placebo

(N=3237)

n (%)< 3.5 273 (8.4) 424 (13.1) >5.5 508 (15.6) 363 (11.2) ≥ 6.0 180 (5.5) 126 (3.9) Table 6 shows the rates of hyperkalemia in EPHESUS as assessed by baseline renal function (creatinine clearance).

Table 6. Rates of Hyperkalemia ( >5.5 mEq/L) in EPHESUS by Baseline Creatinine Clearance* Baseline Creatinine Clearance INSPRA

(N=508)

n (%)Placebo

(N=363)

n (%)- * Estimated using the Cockroft-Gault formula.

≤30 mL/min 160 (32) 82 (23) 31–50 mL/min 122 (24) 46 (13) 51–70 mL/min 86 (17) 48 (13) >70 mL/min 56 (11) 32 (9) Table 7 shows the rates of hyperkalemia in EPHESUS as assessed by two baseline characteristics: presence/absence of proteinuria from baseline urinalysis and presence/absence of diabetes. [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1).]

Table 7. Rates of Hyperkalemia ( >5.5 mEq/L) in EPHESUS by Proteinuria and History of Diabetes* INSPRA

(N=508)

n (%)Placebo

(N=363)

n (%)- * Diabetes assessed as positive medical history at baseline; proteinuria assessed by positive dipstick urinalysis at baseline.

Proteinuria, no Diabetes 81 (16) 40 (11) Diabetes, no Proteinuria 91 (18) 47 (13) Proteinuria and Diabetes 132 (26) 58 (16) Hypertension

Potassium: In placebo-controlled fixed-dose studies, the mean increases in serum potassium were dose-related and are shown in Table 8 along with the frequencies of values >5.5 mEq/L.

Table 8. Increases in Serum Potassium in the Placebo-Controlled, Fixed-Dose Hypertension Studies of INSPRA Mean Increase mEq/L % >5.5 mEq/L Daily Dosage n Placebo 194 0 1 25 97 0.08 0 50 245 0.14 0 100 193 0.09 1 200 139 0.19 1 400 104 0.36 8.7 Patients with both type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria are at increased risk of developing persistent hyperkalemia. In a study of such patients taking INSPRA 200 mg, the frequencies of maximum serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L were 33% with INSPRA given alone and 38% when INSPRA was given with enalapril.

Rates of hyperkalemia increased with decreasing renal function. In all studies, serum potassium elevations >5.5 mEq/L were observed in 10.4% of patients treated with INSPRA with baseline calculated creatinine clearance <70 mL/min, 5.6% of patients with baseline creatinine clearance of 70 to 100 mL/min, and 2.6% of patients with baseline creatinine clearance of >100 mL/min. [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1).]

Sodium: Serum sodium decreased in a dose-related manner. Mean decreases ranged from 0.7 mEq/L at 50 mg daily to 1.7 mEq/L at 400 mg daily. Decreases in sodium (<135 mEq/L) were reported for 2.3% of patients administered INSPRA and 0.6% of placebo-treated patients.

Triglycerides: Serum triglycerides increased in a dose-related manner. Mean increases ranged from 7.1 mg/dL at 50 mg daily to 26.6 mg/dL at 400 mg daily. Increases in triglycerides (above 252 mg/dL) were reported for 15% of patients administered INSPRA and 12% of placebo-treated patients.

Cholesterol: Serum cholesterol increased in a dose-related manner. Mean changes ranged from a decrease of 0.4 mg/dL at 50 mg daily to an increase of 11.6 mg/dL at 400 mg daily. Increases in serum cholesterol values greater than 200 mg/dL were reported for 0.3% of patients administered INSPRA and 0% of placebo-treated patients.

Liver Function Tests: Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) increased in a dose-related manner. Mean increases ranged from 0.8 U/L at 50 mg daily to 4.8 U/L at 400 mg daily for ALT and 3.1 U/L at 50 mg daily to 11.3 U/L at 400 mg daily for GGT. Increases in ALT levels greater than 120 U/L (3 times upper limit of normal) were reported for 15/2259 patients administered INSPRA and 1/351 placebo-treated patients. Increases in ALT levels greater than 200 U/L (5 times upper limit of normal) were reported for 5/2259 of patients administered INSPRA and 1/351 placebo-treated patients. Increases of ALT greater than 120 U/L and bilirubin greater than 1.2 mg/dL were reported 1/2259 patients administered INSPRA and 0/351 placebo-treated patients. Hepatic failure was not reported in patients receiving INSPRA.

BUN/Creatinine: Serum creatinine increased in a dose-related manner. Mean increases ranged from 0.01 mg/dL at 50 mg daily to 0.03 mg/dL at 400 mg daily. Increases in blood urea nitrogen to greater than 30 mg/dL and serum creatinine to greater than 2 mg/dL were reported for 0.5% and 0.2%, respectively, of patients administered INSPRA and 0% of placebo-treated patients.

Uric Acid: Increases in uric acid to greater than 9 mg/dL were reported in 0.3% of patients administered INSPRA and 0% of placebo-treated patients.

6.3 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of INSPRA. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Skin: angioneurotic edema, rash

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 CYP3A4 Inhibitors

Because eplerenone metabolism is predominantly mediated via CYP3A4, do not use INSPRA with drugs that are strong inhibitors of CYP3A4. [See CONTRAINDICATIONS (4) and CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

In patients with hypertension taking moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, reduce the starting dose of INSPRA to 25 mg once daily. [See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (2.3,2.4) and CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY (12.3).]

7.2 ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists

Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

In EPHESUS [see CLINICAL STUDIES (14.1)], 3020 (91%) patients receiving INSPRA 25 to 50 mg also received ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ACEI/ARB). Rates of patients with maximum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L were similar regardless of the use of ACEI/ARB.

Hypertension

In clinical studies of patients with hypertension, the addition of INSPRA 50 to 100 mg to ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists increased mean serum potassium slightly (about 0.09–0.13 mEq/L). In a study in diabetics with microalbuminuria, INSPRA 200 mg combined with the ACE inhibitor enalapril 10 mg increased the frequency of hyperkalemia (serum potassium >5.5 mEq/L) from 17% on enalapril alone to 38%.

7.3 Lithium

A drug interaction study of eplerenone with lithium has not been conducted. Lithium toxicity has been reported in patients receiving lithium concomitantly with diuretics and ACE inhibitors. Serum lithium levels should be monitored frequently if INSPRA is administered concomitantly with lithium.

7.4 Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

A drug interaction study of eplerenone with an NSAID has not been conducted. The administration of other potassium-sparing antihypertensives with NSAIDs has been shown to reduce the antihypertensive effect in some patients and result in severe hyperkalemia in patients with impaired renal function. Therefore, when INSPRA and NSAIDs are used concomitantly, patients should be observed to determine whether the desired effect on blood pressure is obtained and monitored for changes in serum potassium levels.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category B

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. INSPRA should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Teratogenic Effects

Embryo-fetal development studies were conducted with doses up to 1000 mg/kg/day in rats and 300 mg/kg/day in rabbits (exposures up to 32 and 31 times the human AUC for the 100 mg/day therapeutic dose, respectively). No teratogenic effects were seen in rats or rabbits, although decreased body weight in maternal rabbits and increased rabbit fetal resorptions and post-implantation loss were observed at the highest administered dosage. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, INSPRA should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

The concentration of eplerenone in human breast milk after oral administration is unknown. However, preclinical data show that eplerenone and/or metabolites are present in rat breast milk (0.85:1 [milk:plasma] AUC ratio) obtained after a single oral dose. Peak concentrations in plasma and milk were obtained from 0.5 to 1 hour after dosing. Rat pups exposed by this route developed normally. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk and because of the unknown potential for adverse effects on the nursing infant, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

8.4 Pediatric Use

In a 10-week study of 304 hypertensive pediatric patients age 4 to 17 years treated with INSPRA up to 100 mg per day, doses that produced exposure similar to that in adults, INSPRA did not lower blood pressure effectively. In this study and in a 1-year pediatric safety study in 149 patients, the incidence of reported adverse events was similar to that of adults.

INSPRA has not been studied in hypertensive patients less than 4 years old because the study in older pediatric patients did not demonstrate effectiveness.

INSPRA has not been studied in pediatric patients with heart failure.

8.5 Geriatric Use

Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

Of the total number of patients in EPHESUS, 3340 (50%) were 65 and over, while 1326 (20%) were 75 and over. Patients greater than 75 years did not appear to benefit from the use of INSPRA. [See CLINICAL STUDIES (14.1).]

No differences in overall incidence of adverse events were observed between elderly and younger patients. However, due to age-related decreases in creatinine clearance, the incidence of laboratory-documented hyperkalemia was increased in patients 65 and older. [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1).]

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

No cases of human overdosage with eplerenone have been reported. Lethality was not observed in mice, rats, or dogs after single oral doses that provided Cmax exposures at least 25 times higher than in humans receiving eplerenone 100 mg/day. Dogs showed emesis, salivation, and tremors at a Cmax 41 times the human therapeutic Cmax, progressing to sedation and convulsions at higher exposures.

The most likely manifestation of human overdosage would be anticipated to be hypotension or hyperkalemia. Eplerenone cannot be removed by hemodialysis. Eplerenone has been shown to bind extensively to charcoal. If symptomatic hypotension should occur, supportive treatment should be instituted. If hyperkalemia develops, standard treatment should be initiated.

-

11 DESCRIPTION

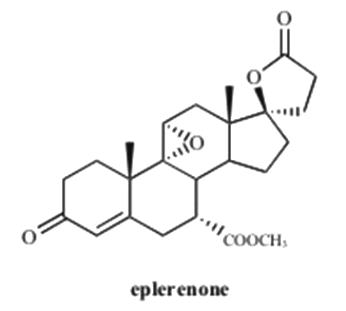

INSPRA contains eplerenone, a blocker of aldosterone binding at the mineralocorticoid receptor.

Eplerenone is chemically described as Pregn-4-ene-7,21-dicarboxylic acid, 9,11-epoxy-17-hydroxy-3-oxo-, γ-lactone, methyl ester, (7α,11α,17α)-. Its empirical formula is C24H30O6 and it has a molecular weight of 414.50. The structural formula of eplerenone is represented below:

Eplerenone is an odorless, white to off-white crystalline powder. It is very slightly soluble in water, with its solubility essentially pH-independent. The octanol/water partition coefficient of eplerenone is approximately 7.1 at pH 7.0.

INSPRA for oral administration contains 25 mg or 50 mg of eplerenone and the following inactive ingredients: lactose, microcrystalline cellulose, croscarmellose sodium, hypromellose, sodium lauryl sulfate, talc, magnesium stearate, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate 80, and iron oxide yellow and iron oxide red.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Eplerenone binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor and blocks the binding of aldosterone, a component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS). Aldosterone synthesis, which occurs primarily in the adrenal gland, is modulated by multiple factors, including angiotensin II and non-RAAS mediators such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and potassium. Aldosterone binds to mineralocorticoid receptors in both epithelial (e.g., kidney) and nonepithelial (e.g., heart, blood vessels, and brain) tissues and increases blood pressure through induction of sodium reabsorption and possibly other mechanisms.

Eplerenone has been shown to produce sustained increases in plasma renin and serum aldosterone, consistent with inhibition of the negative regulatory feedback of aldosterone on renin secretion. The resulting increased plasma renin activity and aldosterone circulating levels do not overcome the effects of eplerenone.

Eplerenone selectively binds to recombinant human mineralocorticoid receptors relative to its binding to recombinant human glucocorticoid, progesterone, and androgen receptors.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Eplerenone is cleared predominantly by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 metabolism, with an elimination half-life of 4 to 6 hours. Steady state is reached within 2 days. Absorption is not affected by food. Inhibitors of CYP3A4 (e.g., ketoconazole, saquinavir) increase blood levels of eplerenone.

Absorption and Distribution

Mean peak plasma concentrations of eplerenone are reached approximately 1.5 hours following oral administration. The absolute bioavailability of eplerenone is 69% following administration of a 100 mg oral tablet. Both peak plasma levels (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) are dose proportional for doses of 25 to 100 mg and less than proportional at doses above 100 mg.

The plasma protein binding of eplerenone is about 50% and it is primarily bound to alpha 1-acid glycoproteins. The apparent volume of distribution at steady state ranged from 43 to 90 L. Eplerenone does not preferentially bind to red blood cells.

Metabolism and Excretion

Eplerenone metabolism is primarily mediated via CYP3A4. No active metabolites of eplerenone have been identified in human plasma.

Less than 5% of an eplerenone dose is recovered as unchanged drug in the urine and feces. Following a single oral dose of radiolabeled drug, approximately 32% of the dose was excreted in the feces and approximately 67% was excreted in the urine. The elimination half-life of eplerenone is approximately 4 to 6 hours. The apparent plasma clearance is approximately 10 L/hr.

Age, Gender, and Race

The pharmacokinetics of eplerenone at a dose of 100 mg once daily has been investigated in the elderly (≥65 years), in males and females, and in Blacks. At steady state, elderly subjects had increases in Cmax (22%) and AUC (45%) compared with younger subjects (18 to 45 years). The pharmacokinetics of eplerenone did not differ significantly between males and females. At steady state, Cmax was 19% lower and AUC was 26% lower in Blacks. [See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (2.4) and USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS (8.5).]

Renal Impairment

The pharmacokinetics of eplerenone was evaluated in patients with varying degrees of renal impairment and in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Compared with control subjects, steady state AUC and Cmax were increased by 38% and 24%, respectively, in patients with severe renal impairment and were decreased by 26% and 3%, respectively, in patients undergoing hemodialysis. No correlation was observed between plasma clearance of eplerenone and creatinine clearance. Eplerenone is not removed by hemodialysis. [See WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.3).]

Hepatic Impairment

The pharmacokinetics of eplerenone 400 mg has been investigated in patients with moderate (Child-Pugh Class B) hepatic impairment and compared with normal subjects. Steady state Cmax and AUC of eplerenone were increased by 3.6% and 42%, respectively.

Heart Failure

The pharmacokinetics of eplerenone 50 mg was evaluated in 8 patients with heart failure (NYHA classification II–IV) and 8 matched (gender, age, weight) healthy controls. Compared with the controls, steady state AUC and Cmax in patients with stable heart failure were 38% and 30% higher, respectively.

Drug-Drug Interactions [See DRUG INTERACTIONS (7).]

Eplerenone is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4. Inhibitors of CYP3A4 cause increased exposure [see DRUG INTERACTIONS (7.1)].

Drug-drug interaction studies were conducted with a 100 mg dose of eplerenone.

A pharmacokinetic study evaluating the administration of a single dose of INSPRA 100 mg with ketoconazole 200 mg two times a day, a strong inhibitor of the CYP3A4 pathway, showed a 1.7-fold increase in Cmax of eplerenone and a 5.4-fold increase in AUC of eplerenone.

Administration of eplerenone with moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., erythromycin 500 mg BID, verapamil 240 mg once daily, saquinavir 1200 mg three times a day, fluconazole 200 mg once daily) resulted in increases in Cmax of eplerenone ranging from 1.4- to 1.6-fold and AUC from 2.0- to 2.9-fold.

Grapefruit juice caused only a small increase (about 25%) in exposure.

Eplerenone is not an inhibitor of CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, or CYP2D6. Eplerenone did not inhibit the metabolism of amiodarone, amlodipine, astemizole, chlorzoxazone, cisapride, dexamethasone, dextromethorphan, diclofenac, 17α-ethinyl estradiol, fluoxetine, losartan, lovastatin, mephobarbital, methylphenidate, methylprednisolone, metoprolol, midazolam, nifedipine, phenacetin, phenytoin, simvastatin, tolbutamide, triazolam, verapamil, and warfarin in vitro. Eplerenone is not a substrate or an inhibitor of P-Glycoprotein at clinically relevant doses.

No clinically significant drug-drug pharmacokinetic interactions were observed when eplerenone was administered with cisapride, cyclosporine, digoxin, glyburide, midazolam, oral contraceptives (norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol), simvastatin, or warfarin. St. John's Wort (a CYP3A4 inducer) caused a small (about 30%) decrease in eplerenone AUC.

No significant changes in eplerenone pharmacokinetics were observed when eplerenone was administered with aluminum- and magnesium-containing antacids.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Eplerenone was non-genotoxic in a battery of assays including in vitro bacterial mutagenesis (Ames test in Salmonella spp. and E. Coli), in vitro mammalian cell mutagenesis (mouse lymphoma cells), in vitro chromosomal aberration (Chinese hamster ovary cells), in vivo rat bone marrow micronucleus formation, and in vivo/ex vivo unscheduled DNA synthesis in rat liver.

There was no drug-related tumor response in heterozygous P53 deficient mice when tested for 6 months at dosages up to 1000 mg/kg/day (systemic AUC exposures up to 9 times the exposure in humans receiving the 100 mg/day therapeutic dose). Statistically significant increases in benign thyroid tumors were observed after 2 years in both male and female rats when administered eplerenone 250 mg/kg/day (highest dose tested) and in male rats only at 75 mg/kg/day. These dosages provided systemic AUC exposures approximately 2 to 12 times higher than the average human therapeutic exposure at 100 mg/day. Repeat dose administration of eplerenone to rats increases the hepatic conjugation and clearance of thyroxin, which results in increased levels of TSH by a compensatory mechanism. Drugs that have produced thyroid tumors by this rodent-specific mechanism have not shown a similar effect in humans.

Male rats treated with eplerenone at 1000 mg/kg/day for 10 weeks (AUC 17 times that at the 100 mg/day human therapeutic dose) had decreased weights of seminal vesicles and epididymides and slightly decreased fertility. Dogs administered eplerenone at dosages of 15 mg/kg/day and higher (AUC 5 times that at the 100 mg/day human therapeutic dose) had dose-related prostate atrophy. The prostate atrophy was reversible after daily treatment for 1 year at 100 mg/kg/day. Dogs with prostate atrophy showed no decline in libido, sexual performance, or semen quality. Testicular weight and histology were not affected by eplerenone in any test animal species at any dosage.

-

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Congestive Heart Failure Post-Myocardial Infarction

The eplerenone post-acute myocardial infarction heart failure efficacy and survival study (EPHESUS) was a multinational, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients clinically stable 3–14 days after an acute myocardial infarction (MI) with left ventricular dysfunction (as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≤40%) and either diabetes or clinical evidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) (pulmonary congestion by exam or chest x-ray or S3). Patients with CHF of valvular or congenital etiology, patients with unstable post-infarct angina, and patients with serum potassium >5.0 mEq/L or serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL were to be excluded. Patients were allowed to receive standard post-MI drug therapy and to undergo revascularization by angioplasty or coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Patients randomized to INSPRA were given an initial dose of 25 mg once daily and titrated to the target dose of 50 mg once daily after 4 weeks if serum potassium was < 5.0 mEq/L. Dosage was reduced or suspended anytime during the study if serum potassium levels were ≥ 5.5 mEq/L. [See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (2.1).]

EPHESUS randomized 6,632 patients (9.3% U.S.) at 671 centers in 27 countries. The study population was primarily white (90%, with 1% Black, 1% Asian, 6% Hispanic, 2% other) and male (71%). The mean age was 64 years (range, 22–94 years). The majority of patients had pulmonary congestion (75%) by exam or x-ray and were Killip Class II (64%). The mean ejection fraction was 33%. The average time to enrollment was 7 days post-MI. Medical histories prior to the index MI included hypertension (60%), coronary artery disease (62%), dyslipidemia (48%), angina (41%), type 2 diabetes (30%), previous MI (27%), and CHF (15%).

The mean dose of INSPRA was 43 mg/day. Patients also received standard care including aspirin (92%), ACE inhibitors (90%), ß-blockers (83%), nitrates (72%), loop diuretics (66%), or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (60%).

Patients were followed for an average of 16 months (range, 0–33 months). The ascertainment rate for vital status was 99.7%.

The co-primary endpoints for EPHESUS were (1) the time to death from any cause, and (2) the time to first occurrence of either cardiovascular (CV) mortality [defined as sudden cardiac death or death due to progression of congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, or other CV causes] or CV hospitalization (defined as hospitalization for progression of CHF, ventricular arrhythmias, acute myocardial infarction, or stroke).

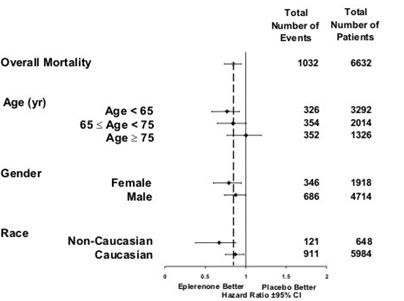

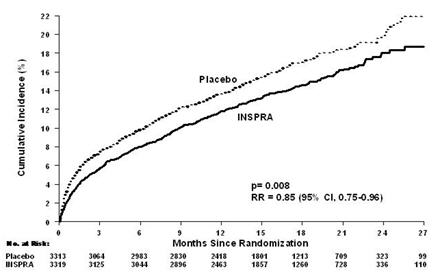

For the co-primary endpoint for death from any cause, there were 478 deaths in the INSPRA group (14.4%) and 554 deaths in the placebo group (16.7%). The risk of death with INSPRA was reduced by 15% [hazard ratio equal to 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.75 to 0.96; p = 0.008 by log rank test)]. Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality are shown in Figure 1 and the components of mortality are provided in Table 9.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of All-Cause Mortality

Table 9. Components of All-Cause Mortality in EPHESUS INSPRA

(N=3319)

n (%)Placebo

(N=3313)

n (%)Hazard

Ratiop-value Death from any cause 478 (14.4) 554 (16.7) 0.85 0.008 CV Death 407 (12.3) 483 (14.6) 0.83 0.005 Non-CV Death 60 (1.8) 54 (1.6) Unknown or unwitnessed death 11 (0.3) 17 (0.5) Most CV deaths were attributed to sudden death, acute MI, and CHF.

The time to first event for the co-primary endpoint of CV death or hospitalization, as defined above, was longer in the INSPRA group (hazard ratio 0.87, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 0.95, p = 0.002). An analysis that included the time to first occurrence of CV mortality and all CV hospitalizations (atrial arrhythmia, angina, CV procedures, progression of CHF, MI, stroke, ventricular arrhythmia, or other CV causes) showed a smaller effect with a hazard ratio of 0.92 (95% confidence interval 0.86 to 0.99; p = 0.028). The combined endpoints, including combined all-cause hospitalization and mortality were driven primarily by CV mortality. The combined endpoints in EPHESUS, including all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality, are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Rates of Death or Hospitalization in EPHESUS Event INSPRA

n (%)Placebo

n (%)- * Co-Primary Endpoint.

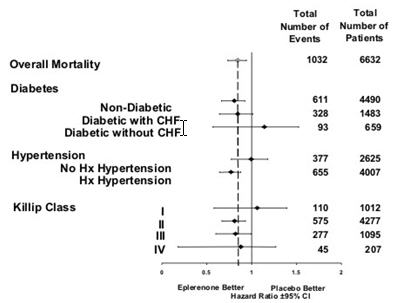

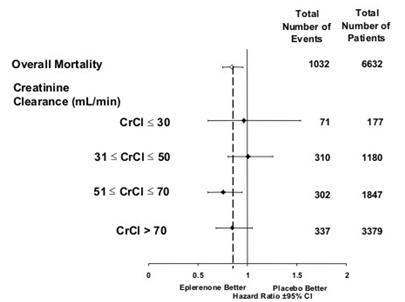

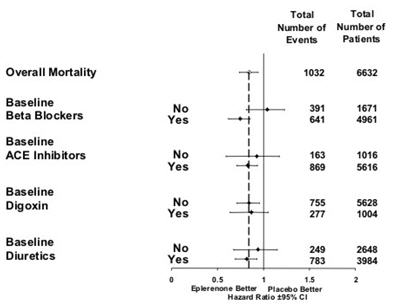

CV death or hospitalization for progression of CHF, stroke, MI or ventricular arrhythmia* 885 (26.7) 993 (30.0) Death 407 (12.3) 483 (14.6) Hospitalization 606 (18.3) 649 (19.6) CV death or hospitalization for progression of CHF, stroke, MI, ventricular arrhythmia, atrial arrhythmia, angina, CV procedures, or other CV causes (PVD; Hypotension) 1516 (45.7) 1610 (48.6) Death 407 (12.3) 483 (14.6) Hospitalization 1281 (38.6) 1307 (39.5) All-cause death or hospitalization 1734 (52.2) 1833 (55.3) Death* 478 (14.4) 554 (16.7) Hospitalization 1497 (45.1) 1530 (46.2) Mortality hazard ratios varied for some subgroups as shown in Figure 2. Mortality hazard ratios appeared favorable for INSPRA for both genders and for all races or ethnic groups, although the numbers of non-Caucasians were low (648, 10%). Patients with diabetes without clinical evidence of CHF and patients greater than 75 years did not appear to benefit from the use of INSPRA. Such subgroup analyses must be interpreted cautiously.

14.2 Hypertension

The safety and efficacy of INSPRA have been evaluated alone and in combination with other antihypertensive agents in clinical studies of 3091 hypertensive patients. The studies included 46% women, 14% Blacks, and 22% elderly (age ≥65). The studies excluded patients with elevated baseline serum potassium (>5.0 mEq/L) and elevated baseline serum creatinine (generally >1.5 mg/dL in males and >1.3 mg/dL in females).

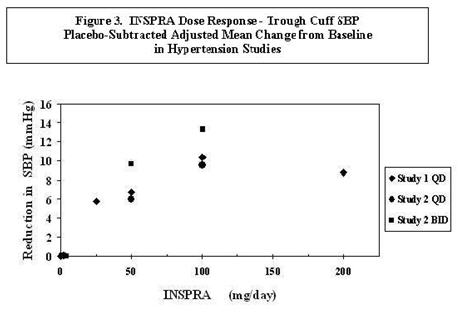

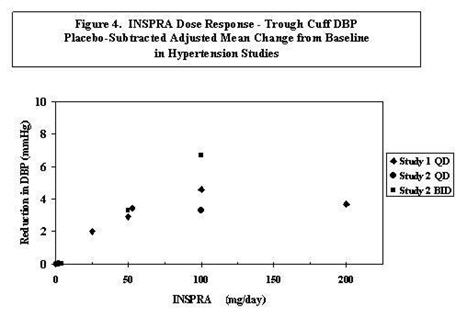

Two fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, 8- to 12-week monotherapy studies in patients with baseline diastolic blood pressures of 95 to 114 mm Hg were conducted to assess the antihypertensive effect of INSPRA. In these two studies, 611 patients were randomized to INSPRA and 140 patients to placebo. Patients received INSPRA in doses of 25 to 400 mg daily as either a single daily dose or divided into two daily doses. The mean placebo-subtracted reductions in trough cuff blood pressure achieved by INSPRA in these studies at doses up to 200 mg are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Patients treated with INSPRA 50 to 200 mg daily experienced significant decreases in sitting systolic and diastolic blood pressure at trough with differences from placebo of 6–13 mm Hg (systolic) and 3–7 mm Hg (diastolic). These effects were confirmed by assessments with 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). In these studies, assessments of 24-hour ABPM data demonstrated that INSPRA, administered once or twice daily, maintained antihypertensive efficacy over the entire dosing interval. However, at a total daily dose of 100 mg, INSPRA administered as 50 mg twice per day produced greater trough cuff (4/3 mm Hg) and ABPM (2/1 mm Hg) blood pressure reductions than 100 mg given once daily.

Blood pressure lowering was apparent within 2 weeks from the start of therapy with INSPRA, with maximal antihypertensive effects achieved within 4 weeks. Stopping INSPRA following treatment for 8 to 24 weeks in six studies did not lead to adverse event rates in the week following withdrawal of INSPRA greater than following placebo or active control withdrawal. Blood pressures in patients not taking other antihypertensives rose 1 week after withdrawal of INSPRA by about 6/3 mm Hg, suggesting that the antihypertensive effect of INSPRA was maintained through 8 to 24 weeks.

Blood pressure reductions with INSPRA in the two fixed-dose monotherapy studies and other studies using titrated doses, as well as concomitant treatments, were not significantly different when analyzed by age, gender, or race with one exception. In a study in patients with low renin hypertension, blood pressure reductions in Blacks were smaller than those in whites during the initial titration period with INSPRA.

INSPRA has been studied concomitantly with treatment with ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, and hydrochlorothiazide. When administered concomitantly with one of these drugs INSPRA usually produced its expected antihypertensive effects.

There was no significant change in average heart rate among patients treated with INSPRA in the combined clinical studies. No consistent effects of INSPRA on heart rate, QRS duration, or PR or QT interval were observed in 147 normal subjects evaluated for electrocardiographic changes during pharmacokinetic studies.

- 16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

-

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Patients receiving INSPRA should be informed:

- Not to use strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, clarithromycin, nefazodone, ritonavir, and nelfinavir.

- Not to use potassium supplements or salt substitutes containing potassium without consulting the prescribing physician.

- To call their physician if they experience dizziness, diarrhea, vomiting, rapid or irregular heartbeat, lower extremity edema, or difficulty breathing.

- That periodic monitoring of blood pressure and serum potassium is important.

[See CONTRAINDICATIONS (4); WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS (5.1); and DRUG INTERACTIONS (7).]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

- Principal Display Panel

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

INSPRA

eplerenone tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 21695-797(NDC:0025-1710) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength eplerenone (UNII: 6995V82D0B) (eplerenone - UNII:6995V82D0B) eplerenone 25 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength lactose (UNII: J2B2A4N98G) cellulose, microcrystalline (UNII: OP1R32D61U) croscarmellose sodium (UNII: M28OL1HH48) HYPROMELLOSES (UNII: 3NXW29V3WO) sodium lauryl sulfate (UNII: 368GB5141J) talc (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) magnesium stearate (UNII: 70097M6I30) titanium dioxide (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) polyethylene glycol (UNII: 3WJQ0SDW1A) polysorbate 80 (UNII: 6OZP39ZG8H) ferric oxide yellow (UNII: EX438O2MRT) ferric oxide red (UNII: 1K09F3G675) Product Characteristics Color YELLOW Score no score Shape DIAMOND (biconvex) Size 7mm Flavor Imprint Code Pfizer;NSR;25 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 21695-797-90 90 in 1 BOTTLE Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA NDA021437 09/27/2002 Labeler - Rebel Distributors Corp (118802834) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Rebel Distributors Corp 118802834 RELABEL, REPACK

Trademark Results [Inspra]

Mark Image Registration | Serial | Company Trademark Application Date |

|---|---|

INSPRA 90517309 not registered Live/Pending |

Shenzhen Hippo Trading Co.,Ltd. 2021-02-08 |

INSPRA 78305153 2925085 Dead/Cancelled |

Pharmacia & Upjohn Company 2003-09-25 |

INSPRA 78188264 not registered Dead/Abandoned |

X.J. Group USA 2002-11-23 |

INSPRA 76607097 3000360 Dead/Cancelled |

PHARMACIA & UPJOHN COMPANY LLC 2004-08-16 |

INSPRA 75861567 2865357 Live/Registered |

PHARMACIA & UPJOHN COMPANY LLC 1999-12-01 |

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.