Kelnor® 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) (ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets USP)

Kelnor 1/35 by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Kelnor 1/35 by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by A-S Medication Solutions. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

KELNOR 1/35- ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol

A-S Medication Solutions

----------

Kelnor® 1/35 (28 Day Regimen)

(ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl

estradiol tablets USP)

Patients should be counseled that this product does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

DESCRIPTION

Kelnor® 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) (ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets USP): Each light yellow tablet contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate, USP and 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, USP. The inactive ingredients include anhydrous lactose, D&C yellow no. 10 aluminum lake, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, polacrilin potassium, and povidone. Each white tablet is a placebo containing only inert ingredients as follows: anhydrous lactose, hypromellose, magnesium stearate, and microcrystalline cellulose.

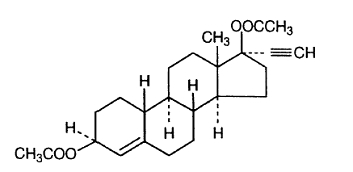

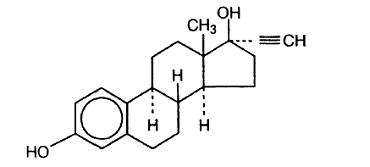

The chemical name for ethynodiol diacetate, USP is 19-nor-17α-pregn-4-en-20-yne-3β, 17-diol diacetate, and for ethinyl estradiol, USP it is 19-nor-17α-pregna-1, 3, 5 (10)-trien-20-yne-3, 17-diol. The structural formulas are as follows:

Ethynodiol Diacetate, USP

C24H32O4 M.W. 384.51

Ethinyl Estradiol, USP

- C20H24O2 M.W. 296.40

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Combination oral contraceptives act primarily by suppression of gonadotropins. Although the primary mechanism of this action is inhibition of ovulation, other alterations in the genital tract, including changes in the cervical mucus (which increase the difficulty of sperm entry into the uterus) and the endometrium (which may reduce the likelihood of implantation) may also contribute to contraceptive effectiveness.

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Kelnor 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) (ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets) is indicated for the prevention of pregnancy in women who elect to use oral contraceptives as a method of contraception.

Oral contraceptives are highly effective. Table 1 lists the typical accidental pregnancy rates for users of combination oral contraceptives and other methods of contraception. The efficacy of these contraceptive methods, except sterilization and progestogen implants and injections, depends upon the reliability with which they are used. Correct and consistent use of methods can result in lower failure rates.

|

|

|||

| % of Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy Within the First Year of Use | % of Women Continuing Use at One Year* |

||

| Method (1) | Typical Use† (2) | Perfect Use‡ (3) | (4) |

| Chance§ | 85 | 85 | |

| Spermicides¶ | 26 | 6 | 40 |

| Periodic abstinence | 25 | 63 |

|

| Calendar | 9 | ||

| Ovulation method | 3 | ||

| Sympto-thermal# | 2 | ||

| Post-ovulation | 1 | ||

| Withdrawal | 19 | 4 | |

| CapÞ | |||

| Parous women | 40 | 26 | 42 |

| Nulliparous women | 20 | 9 | 56 |

| Sponge | |||

| Parous women | 40 | 20 | 42 |

| Nulliparous women | 20 | 9 | 56 |

| DiaphragmÞ | 20 | 6 | 56 |

| Condomß | |||

| Female (Reality®) | 21 | 5 | 56 |

| Male | 14 | 3 | 61 |

| Pill | 5 | 71 |

|

| Progestin only | 0.5 | ||

| Combined | 0.1 | ||

| IUD | |||

| Progesterone T | 2 | 1.5 | 81 |

| Copper T 380A | 0.8 | 0.6 | 78 |

| LNg 20 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 81 |

| Injection (Depo-Provera®) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 70 |

| Implant (Norplant® and Norplant-2®) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 88 |

| Female sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| Male sterilization | 0.15 | 0.1 | 100 |

| Emergency Contraceptive Pills: Treatment initiated within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse reduces the risk of pregnancy by at least 75%.à |

|||

| Lactational Amenorrhea Method: LAM is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception.è |

|||

| Source: Trussell J, Contraceptive efficacy. In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Stewart F, Cates W, Stewart GK, Kowal D, Guest F, Contraceptive Technology: Seventeenth Revised Edition. New York, NY: Irvington Publishers, 1998, in press.1 |

|||

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Oral contraceptives should not be used in women who have the following conditions:

- Thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders

- A past history of deep vein thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders

- Cerebral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, or coronary artery disease, or a past history of these conditions

- Known or suspected carcinoma of the breast, or a history of this condition

- Known or suspected carcinoma of the female reproductive organs or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia, or a history of these conditions

- Undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding

- History of cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy or jaundice with prior oral contraceptive use

- Past or present, benign or malignant liver tumors

- Known or suspected pregnancy

- Are receiving Hepatitis C drug combinations containing ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir, due to the potential for ALT elevations (see WARNINGS, Risk of Liver Enzyme Elevations with Concomitant Hepatitis C Treatment).

WARNINGS

| Cigarette smoking increases the risk of serious cardiovascular side effects from oral contraceptive use. This risk increases with age and with heavy smoking (15 or more cigarettes per day) and is quite marked in women over 35 years of age. Women who use oral contraceptives should be strongly advised not to smoke. |

The use of oral contraceptives is associated with increased risk of several serious conditions including venous and arterial thromboembolism, thrombotic and hemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, liver tumors or other liver lesions, and gallbladder disease. The risk of morbidity and mortality increases significantly in the presence of other risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.

Practitioners prescribing oral contraceptives should be familiar with the following information relating to these and other risks.

The information contained herein is principally based on studies carried out in patients who used oral contraceptives with formulations containing higher amounts of estrogens and progestogens than those in common use today. The effect of long-term use of the oral contraceptives with lesser amounts of both estrogens and progestogens remains to be determined.

Throughout this labeling, epidemiological studies reported are of two types: retrospective case-control studies and prospective cohort studies. Case-control studies provide an estimate of the relative risk of a disease, which is defined as the ratio of the incidence of a disease among oral contraceptive users to that among nonusers. The relative risk (or odds ratio) does not provide information about the actual clinical occurrence of a disease. Cohort studies provide a measure of both the relative risk and the attributable risk. The latter is the difference in the incidence of disease between oral contraceptive users and nonusers. The attributable risk does provide information about the actual occurrence or incidence of a disease in the subject population. For further information, the reader is referred to a text on epidemiological methods.

1. Thromboembolic Disorders and Other Vascular Problems

a. Myocardial Infarction

An increased risk of myocardial infarction has been associated with oral contraceptive use.2-21 This increased risk is primarily in smokers or in women with other underlying risk factors for coronary artery disease such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. The relative risk for myocardial infarction in current oral contraceptive users has been estimated to be 2 to 6. The risk is very low under the age of 30. However, there is the possibility of a risk of cardiovascular disease even in very young women who take oral contraceptives.

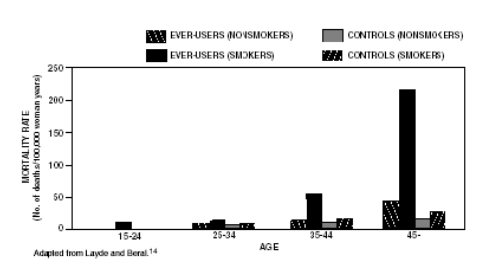

Smoking in combination with oral contraceptive use has been reported to contribute substantially to the risk of myocardial infarction in women in their mid-thirties or older, with smoking accounting for the majority of excess cases.22 Mortality rates associated with circulatory disease have been shown to increase substantially in smokers, especially in those 35 years of age and older among women who use oral contraceptives (see Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1. Circulatory disease mortality rates per 100,000 woman-years by age, smoking status, and oral contraceptive use.14

Oral contraceptives may compound the effects of well-known cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemias, hypercholesterolemia, age, cigarette smoking, and obesity. In particular, some progestogens decrease HDL cholesterol23-31 and cause glucose intolerance, while estrogens may create a state of hyperinsulinism.32 Oral contraceptives have been shown to increase blood pressure among some users (see WARNINGS, No. 10). Similar effects on risk factors have been associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

b. Thromboembolism

An increased risk of thromboembolic and thrombotic disease associated with the use of oral contraceptives is well established.17, 33-51 Case-control studies have estimated the relative risk to be 3 for the first episode of superficial venous thrombosis, 4 to 11 for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and 1.5 to 6 for women with predisposing conditions for venous thromboembolic disease.34-37, 45, 46 Cohort studies have shown the relative risk to be somewhat lower, about 3 for new cases (subjects with no past history of venous thrombosis or varicose veins) and about 4.5 for new cases requiring hospitalization.42, 47, 48 The risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with oral contraceptives is not related to duration of use.

A two- to seven-fold increase in relative risk of postoperative thromboembolic complications has been reported with the use of oral contraceptives.38, 39 The relative risk of venous thrombosis in women who have predisposing conditions is about twice that of women without such medical conditions.43 If feasible, oral contraceptives should be discontinued at least 4 weeks prior to and for 2 weeks after elective surgery of a type associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, and also during and following prolonged immobilization. Since the immediate postpartum period is also associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, oral contraceptives should be started no earlier than 4 to 6 weeks after delivery in women who elect not to breastfeed.

c. Cerebrovascular Diseases

Both the relative and attributable risks of cerebrovascular events (thrombotic and hemorrhagic strokes) have been reported to be increased with oral contraceptive use,14, 17, 18, 34, 42, 46, 52-59 although, in general, the risk was greatest among older (over 35 years), hypertensive women who also smoked. Hypertension was reported to be a risk factor for both users and nonusers, for both types of strokes, while smoking increased the risk for hemorrhagic strokes.

In one large study,52 the relative risk for thrombotic stroke was reported as 9.5 times greater in users than in nonusers. It ranged from 3 for normotensive users to 14 for users with severe hypertension.54 The relative risk for hemorrhagic stroke was reported to be 1.2 for nonsmokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.9 to 2.6 for smokers who did not use oral contraceptives, 6.1 to 7.6 for smokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.8 for normotensive users, and 25.7 for users with severe hypertension. The risk is also greater in older women and among smokers.

d. Dose-Related Risk of Vascular Disease With Oral Contraceptives

A positive association has been reported between the amount of estrogen and progestogen in oral contraceptives and the risk of vascular disease.41, 43, 53, 59-64 A decline in serum high density lipoproteins (HDL) has been reported with many progestogens.23-31 A decline in serum high density lipoproteins has been associated with an increased incidence of ischemic heart disease.65 Because estrogens increase HDL-cholesterol, the net effect of an oral contraceptive depends on the balance achieved between doses of estrogen and progestogen and the nature and absolute amount of progestogens used in the contraceptives. The amount of both steroids should be considered in the choice of an oral contraceptive.

Minimizing exposure to estrogen and progestogen is in keeping with good principles of therapeutics. For any particular estrogen-progestogen combination, the dosage regimen prescribed should be one that contains the least amount of estrogen and progestogen that is compatible with a low failure rate and the needs of the individual patient. New acceptors of oral contraceptives should be started on preparations containing the lowest estrogen content that produces satisfactory results in the individual.

e. Persistence of Risk of Vascular Disease

There are three studies that have shown persistence of risk of vascular disease for users of oral contraceptives. In a study in the United States, the risk of developing myocardial infarction after discontinuing oral contraceptives persisted for at least 9 years for women 40 to 49 years old who had used oral contraceptives for 5 or more years, but this increased risk was not demonstrated in other age groups.16 Another American study reported former use of oral contraceptives was significantly associated with increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage.57 In another study, in Great Britain, the risk of developing nonrheumatic heart disease plus hypertension, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral thrombosis, and transient ischemic attacks persisted for at least 6 years after discontinuation of oral contraceptives, although the excess risk was small.14, 18, 66 It should be noted that these studies were performed with oral contraceptive formulations containing 50 mcg or more of estrogens.

2. Estimates of Mortality From Contraceptive Use

One study67 gathered data from a variety of sources that have estimated the mortality rates associated with different methods of contraception at different ages (Table 2). These estimates include the combined risk of death associated with contraceptive methods plus the risk attributable to pregnancy in the event of method failure. Each method of contraception has its specific benefits and risks. The study concluded that, with the exception of oral contraceptive users 35 and older who smoke and 40 or older who do not smoke, mortality associated with all methods of birth control is low and below that associated with childbirth. The observation of a possible increase in risk of mortality with age for oral contraceptive users is based on data gathered in the 1970's, but not reported until 1983.67 However, current clinical practice involves the use of lower estrogen dose formulations combined with careful restriction of oral contraceptive use to women who do not have the various risk factors listed in this labeling.

Because of these changes in practice and, also, because of some limited new data that suggest that the risk of cardiovascular disease with the use of oral contraceptives may now be less than previously observed,48, 152 the Fertility and Maternal Health Drugs Advisory Committee was asked to review the topic in 1989. The Committee concluded that, although cardiovascular disease risks may be increased with oral contraceptive use after age 40 in healthy nonsmoking women (even with the newer low-dose formulations), there are greater potential health risks associated with pregnancy in older women and with the alternative surgical and medical procedures that may be necessary if such women do not have access to effective and acceptable means of contraception.

Therefore, the Committee recommended that the benefits of oral contraceptive use by healthy nonsmoking women over 40 may outweigh the possible risks. Of course, older women, as all women who take oral contraceptives, should take the lowest possible dose formulation that is effective.

|

|

||||||

| Age |

||||||

| Method of Control | 15 to 19 | 20 to 24 | 25 to 29 | 30 to 34 | 35 to 39 | 40 to 44 |

| No fertility control methods* | 7 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 14.8 | 25.7 | 28.2 |

| Oral contraceptives | ||||||

| nonsmoker† | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 13.8 | 31.6 |

| smoker† | 2.2 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 13.5 | 51.1 | 117.2 |

| IUD† | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Condom* | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Diaphragm/Spermicide* | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Periodic abstinence* | 2.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

Adapted from Ory.67

3. Carcinoma of the Breast and Reproductive Organs

Numerous epidemiological studies have been performed on the incidence of breast, endometrial, ovarian, and cervical cancer in women using oral contraceptives. While there are conflicting reports, many studies suggest that the use of oral contraceptives is not associated with an overall increase in the risk of developing breast cancer.17, 40, 68-78 Other studies, however, have reported an increased risk overall,153-155 or in certain subgroups. In these studies, increased risk has been associated with long duration of use, use beginning at a young age, use before the first term pregnancy, use by those who had an early menarche, those who had a positive family history of breast cancer, or in nulliparas.79-102, 151, 156-162 These risks have been surveyed in two books163-164 and in review articles.85, 99, 153, 165-167

Some studies suggested that oral contraceptive use was associated with an increase in the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, dysplasia, erosion, carcinoma, or microglandular dysplasia in some populations of women.17, 50, 103-115 However, there continues to be controversy about the extent to which such findings may be due to differences in sexual behavior and other factors.

In spite of many studies of the relationship between oral contraceptive use and breast and cervical cancers, a cause and effect relationship has not been established.

4. Hepatic Neoplasia

Benign hepatic adenomas and other hepatic lesions have been associated with oral contraceptive use,116-121 although the incidence of such benign tumors is rare in the United States. Indirect calculations have estimated the attributable risk to be in the range of 3.3 cases per 100,000 for users, a risk that increases after 4 or more years of use.120 Rupture of benign, hepatic adenomas or other lesions may cause death through intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Therefore, such lesions should be considered in women presenting with abdominal pain and tenderness, abdominal mass, or shock. About one quarter of the cases presented because of abdominal masses; up to one half had signs and symptoms of acute intraperitoneal hemorrhage.121 Diagnosis may prove difficult.

Studies from the U.S.,122, 150 Great Britain,123, 124 and Italy125 have shown an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in long-term (> 8 years; relative risk of 7 to 20) oral contraceptive users. However, these cancers are rare in the United States, and the attributable risk (the excess incidence) of liver cancers in oral contraceptive users approaches less than 1 per 1,000,000 users.

5. Risk of Liver Enzyme Elevations with Concomitant Hepatitis C Treatment

During clinical trials with the Hepatitis C combination drug regimen that contains ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir, ALT elevations greater than 5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), including some cases greater than 20 times the ULN, were significantly more frequent in women using ethinyl estradiol-containing medications such as COCs. Discontinue Kelnor prior to starting therapy with the combination drug regimen ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir (see CONTRAINDICATIONS). Kelnor can be restarted approximately 2 weeks following completion of treatment with the combination drug regimen.

6. Ocular Lesions

There have been reports of retinal thrombosis and other ocular lesions associated with the use of oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives should be discontinued if there is unexplained, gradual or sudden, partial or complete loss of vision; onset of proptosis or diplopia; papilledema; or any evidence of retinal vascular lesions. Appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures should be undertaken immediately.

7. Oral Contraceptive Use Before or During Pregnancy

Extensive epidemiological studies have revealed no increased risk of birth defects in women who have used oral contraceptives prior to pregnancy.126, 129 The majority of recent studies also do not suggest a teratogenic effect, particularly insofar as cardiac anomalies and limb reduction defects are concerned,126-129 when the pill is taken inadvertently during early pregnancy.

The administration of oral contraceptives to induce withdrawal bleeding should not be used as a test for pregnancy. Oral contraceptives should not be used during pregnancy to treat threatened or habitual abortion. It is recommended that for any patient who has missed two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing oral contraceptive use. If the patient has not adhered to the prescribed schedule, the possibility of pregnancy should be considered at the time of the first missed period and further use of oral contraceptives should be withheld until pregnancy has been ruled out. Oral contraceptive use should be discontinued if pregnancy is confirmed.

8. Gallbladder Disease

Earlier studies reported an increased lifetime relative risk of gallbladder surgery in users of oral contraceptives and estrogens.40, 42, 53, 70 More recent studies, however, have shown that the relative risk of developing gallbladder disease among oral contraceptive users may be minimal.130-132 The recent findings of minimal risk may be related to the use of oral contraceptive formulations containing lower doses of estrogens and progestogens.

9. Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolic Effects

Oral contraceptives have been shown to cause a decrease in glucose tolerance in a significant percentage of users.32 This effect has been shown to be directly related to estrogen dose.133 Progestogens increase insulin secretion and create insulin resistance, the effect varying with different progestational agents.32, 134 However, in the nondiabetic woman, oral contraceptives appear to have no effect on fasting blood glucose. Because of these demonstrated effects, prediabetic and diabetic women should be carefully observed while taking oral contraceptives.

Some women may have persistent hypertriglyceridemia while on the pill. As discussed earlier (see WARNINGS, 1a and 1d), changes in serum triglycerides and lipoprotein levels have been reported in oral contraceptive users.23-31, 135, 136

10. Elevated Blood Pressure

An increase in blood pressure has been reported in women taking oral contraceptives50, 53, 137-139 and this increase is more likely in older oral contraceptive users137 and with extended duration of use.53 Data from the Royal College of General Practitioners138 and subsequent randomized trials have shown that the incidence of hypertension increases with increasing concentrations of progestogens.

Women with a history of hypertension or hypertension-related disease, or renal disease139 should be encouraged to use another method of contraception. If such women elect to use oral contraceptives, they should be monitored closely and if significant elevation of blood pressure occurs, oral contraceptives should be discontinued. For most women, elevated blood pressure will return to normal after stopping oral contraceptives,137 and there is no difference in the occurrence of hypertension among ever- and never-users.140

11. Headache

The onset or exacerbation of migraine or the development of headache of a new pattern that is recurrent, persistent, or severe requires discontinuation of oral contraceptives and evaluation of the cause.

12. Bleeding Irregularities

Breakthrough bleeding and spotting are sometimes encountered in patients on oral contraceptives, especially during the first three months of use. Nonhormonal causes should be considered and adequate diagnostic measures taken to rule out malignancy or pregnancy in the event of breakthrough bleeding, as in the case of any abnormal vaginal bleeding. If a pathologic basis has been excluded, time alone or a change to another formulation may solve the problem. In the event of amenorrhea, pregnancy should be ruled out. Some women may encounter post-pill amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea, especially when such a condition was pre-existent.

PRECAUTIONS

1. Physical Examination and Follow-Up

It is good medical practice for all women to have annual history and physical examinations, including women using oral contraceptives. The physical examination, however, may be deferred until after initiation of oral contraceptives if requested by the woman and judged appropriate by the clinician. The physical examination should include special reference to blood pressure, breasts, abdomen, and pelvic organs, including cervical cytology, and relevant laboratory tests. In case of undiagnosed, persistent, or recurrent abnormal vaginal bleeding, appropriate measures should be conducted to rule out malignancy. Women with a strong family history of breast cancer or who have breast nodules should be monitored with particular care.

2. Lipid Disorders

Women who are being treated for hyperlipidemias should be followed closely if they elect to use oral contraceptives. Some progestogens may elevate LDL levels and may render the control of hyperlipidemias more difficult.

3. Liver Function

If jaundice develops in any woman receiving oral contraceptives, they should be discontinued. Steroids may be poorly metabolized in patients with impaired liver function and should be administered with caution in such patients. Cholestatic jaundice has been reported after combined treatment with oral contraceptives and troleandomycin. Hepatotoxicity following a combination of oral contraceptives and cyclosporine has also been reported.

4. Fluid Retention

Oral contraceptives may cause some degree of fluid retention. They should be prescribed with caution, and only with careful monitoring, in patients with conditions that might be aggravated by fluid retention, such as convulsive disorders, migraine syndrome, asthma, or cardiac, hepatic, or renal dysfunction.

5. Emotional Disorders

Women with a history of depression should be carefully observed and the drug discontinued if depression recurs to a serious degree.

6. Contact Lenses

Contact lens wearers who develop visual changes or changes in lens tolerance should be assessed by an ophthalmologist.

7. Drug Interactions

Reduced efficacy and increased incidence of breakthrough bleeding and menstrual irregularities have been associated with concomitant use of rifampin. A similar association, though less marked, has been suggested for barbiturates, phenylbutazone, phenytoin sodium, and possibly with griseofulvin, ampicillin, and tetracyclines. Administration of troglitazone concomitantly with a combination oral contraceptive (estrogen and progestin) reduced the plasma concentrations of both hormones by approximately 30%. This could result in loss of contraceptive efficacy.

Concomitant Use with HCV Combination Therapy – Liver Enzyme Elevation

Do not co-administer Kelnor with HCV drug combinations containing ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir, due to potential for ALT elevations (see WARNINGS, Risk of Liver Enzyme Elevations with Concomitant Hepatitis C Treatment).

8. Laboratory Test Interactions

Certain endocrine and liver function tests and blood components may be affected by oral contraceptives:

- Increased prothrombin and factors VII, VIII, IX and X; decreased antithrombin III; increased platelet aggregability.

- Increased thyroid binding globulin (TBG), leading to increased circulating total thyroid hormone as measured by protein-bound iodine (PBI), T4 by column or by radioimmunoassay. Free T3 resin uptake is decreased, reflecting the elevated TBG; free T4 concentration is unaltered.

- Other binding proteins may be elevated in the serum.

- Sex-steroid binding globulins are increased and result in elevated levels of total circulating sex steroids and corticoids; however, free or biologically active levels remain unchanged.

- Triglycerides and phospholipids may be increased.

- Glucose tolerance may be decreased.

- Serum folate levels may be depressed. This may be of clinical significance if a woman becomes pregnant shortly after discontinuing oral contraceptives.

- Increased sulfobromophthalein and other abnormalities in liver function tests may occur.

- Plasma levels of trace minerals may be altered.

- Response to the metyrapone test may be reduced.

11. Nursing Mothers

Small amounts of oral contraceptive steroids have been identified in the milk of nursing mothers141-143 and a few adverse effects on the child have been reported, including jaundice and breast enlargement. In addition, oral contraceptives given in the postpartum period may interfere with lactation by decreasing the quantity and quality of breast milk. If possible, the nursing mother should be advised not to use oral contraceptives, but to use other forms of contraception until she has completely weaned her child.

12. Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy of Kelnor has been established in women of reproductive age. Safety and efficacy are expected to be the same for postpubertal adolescents under the age of 16 and for users 16 years and older. Use of this product before menarche is not indicated.

13. Venereal Diseases

Oral contraceptives are of no value in the prevention or treatment of venereal disease. The prevalence of cervical Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in oral contraceptive users is increased several-fold.144, 145 It should not be assumed that oral contraceptives afford protection against pelvic inflammatory disease from chlamydia.144 Patients should be counseled that this product does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

14. General

a. The pathologist should be advised of oral contraceptive therapy when relevant specimens are submitted.

b. Treatment with oral contraceptives may mask the onset of the climacteric. (See WARNINGS regarding risks in this age group.)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

An increased risk of the following serious adverse reactions has been associated with the use of oral contraceptives (see WARNINGS):

- Thrombophlebitis and thrombosis

- Arterial thromboembolism

- Pulmonary embolism

- Myocardial infarction and coronary thrombosis

- Cerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral thrombosis

- Hypertension

- Gallbladder disease

- Benign and malignant liver tumors, and other hepatic lesions

There is evidence of an association between the following conditions and the use of oral contraceptives, although additional confirmatory studies are needed:

- Mesenteric thrombosis

- Neuro-ocular lesions (e.g., retinal thrombosis and optic neuritis)

The following adverse reactions have been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives and are believed to be drug-related:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (such as abdominal cramps and bloating)

- Breakthrough bleeding

- Spotting

- Change in menstrual flow

- Amenorrhea during or after use

- Temporary infertility after discontinuation of use

- Edema

- Chloasma or melasma, which may persist

- Breast changes: tenderness, enlargement, secretion

- Change in weight (increase or decrease)

- Change in cervical erosion or secretion

- Diminution in lactation when given immediately postpartum

- Cholestatic jaundice

- Migraine

- Rash (allergic)

- Mental depression

- Reduced tolerance to carbohydrates

- Vaginal candidiasis

- Change in corneal curvature (steepening)

- Intolerance to contact lenses

The following adverse reactions or conditions have been reported in users of oral contraceptives and the association has been neither confirmed nor refuted:

- Premenstrual syndrome

- Cataracts

- Changes in appetite

- Cystitis-like syndrome

- Headache

- Nervousness

- Dizziness

- Hirsutism

- Loss of scalp hair

- Erythema multiforme

- Erythema nodosum

- Hemorrhagic eruption

- Vaginitis

- Porphyria

- Impaired renal function

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Acne

- Changes in libido

- Colitis

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Endocervical hyperplasia or ectropion

OVERDOSAGE

Serious ill effects have not been reported following acute ingestion of large doses of oral contraceptives by young children.180, 181 Overdosage may cause nausea, and withdrawal bleeding may occur in females.

NON-CONTRACEPTIVE HEALTH BENEFITS

The following non-contraceptive health benefits related to the use of oral contraceptives are supported by epidemiological studies that largely utilized oral contraceptive formulations containing estrogen doses exceeding 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol or 50 mcg of mestranol.148, 149

Effects on Menses

- Increased menstrual cycle regularity

- Decreased blood loss and decreased risk of iron-deficiency anemia

- Decreased frequency of dysmenorrhea

Effects Related to Inhibition of Ovulation

- Decreased risk of functional ovarian cysts

- Decreased risk of ectopic pregnancies

Effects From Long-Term Use

- Decreased risk of fibroadenomas and fibrocystic disease of the breast

- Decreased risk of acute pelvic inflammatory disease

- Decreased risk of endometrial cancer

- Decreased risk of ovarian cancer

- Decreased risk of uterine fibroids

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

To achieve maximum contraceptive effectiveness, oral contraceptives must be taken exactly as directed and at intervals of 24 hours.

IMPORTANT: If the Sunday start schedule is selected, the patient should be instructed to use an additional method of protection until after the first week of administration in the initial cycle. The possibility of ovulation and conception prior to initiation of use should be considered.

Kelnor 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) (ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets)

Dosage Schedule

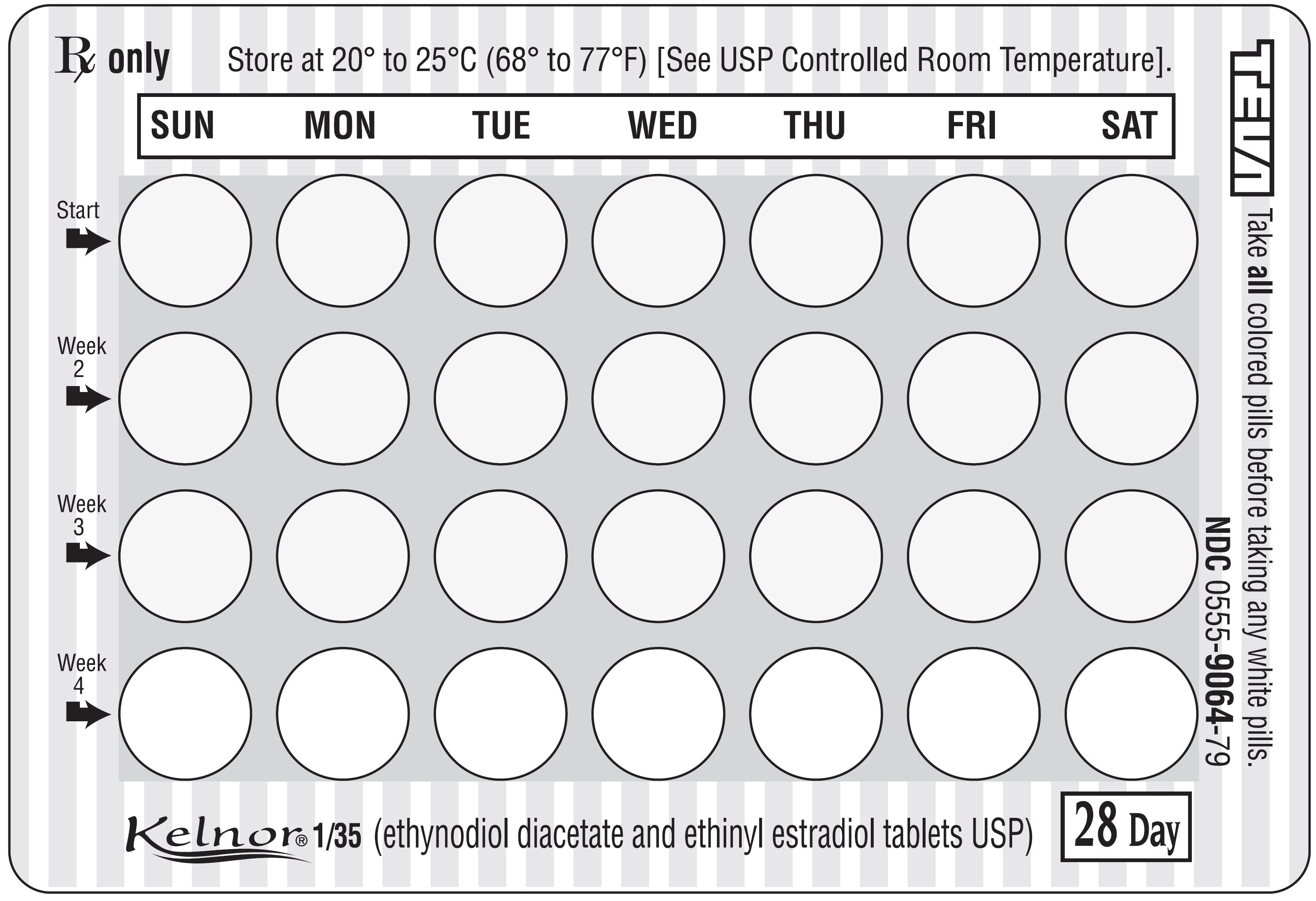

The Kelnor 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) tablet dispenser contains 21 light yellow active tablets arranged in three numbered rows of 7 tablets each, followed by a fourth row of 7 white placebo tablets.

Days of the week are printed above the tablets, starting with Sunday on the left.

28 Day Schedule

For a DAY 1 START, count the first day of menstrual flow as Day 1 and the first tablet (light yellow) is then taken on Day 1. For a SUNDAY START when menstrual flow begins on or before Sunday, the first tablet (light yellow) is taken on that day. With either a DAY 1 START or SUNDAY START, 1 tablet (light yellow) is taken each day at the same time for 21 days. Then the white tablets are taken for 7 days, whether bleeding has stopped or not. After all 28 tablets have been taken, whether bleeding has stopped or not, the same dosage schedule is repeated beginning on the following day.

Special Notes

Spotting, Breakthrough Bleeding, or Nausea

If spotting (bleeding insufficient to require a pad), breakthrough bleeding (heavier bleeding similar to a menstrual flow), or nausea occurs the patient should continue taking her tablets as directed. The incidence of spotting, breakthrough bleeding or nausea is minimal, most frequently occurring in the first cycle. Ordinarily spotting or breakthrough bleeding will stop within a week. Usually the patient will begin to cycle regularly within two to three courses of tablet-taking. In the event of spotting or breakthrough bleeding organic causes should be borne in mind. (See WARNINGS, No. 12.)

Missed Menstrual Periods

Withdrawal flow will normally occur 2 or 3 days after the last active tablet is taken. Failure of withdrawal bleeding ordinarily does not mean that the patient is pregnant, providing the dosage schedule has been correctly followed. (See WARNINGS, No. 7.)

If the patient has not adhered to the prescribed dosage regimen, the possibility of pregnancy should be considered after the first missed period, and oral contraceptives should be withheld until pregnancy has been ruled out.

If the patient has adhered to the prescribed regimen and misses two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing the contraceptive regimen.

The first intermenstrual interval after discontinuing the tablets is usually prolonged; consequently, a patient for whom a 28 day cycle is usual might not begin to menstruate for 35 days or longer. Ovulation in such prolonged cycles will occur correspondingly later in the cycle. Posttreatment cycles after the first one, however, are usually typical for the individual woman prior to taking tablets. (See WARNINGS, No. 12.)

Missed Tablets

If a woman misses taking one active tablet, the missed tablet should be taken as soon as it is remembered. In addition, the next tablet should be taken at the usual time. If two consecutive active tablets are missed in week 1 or week 2 of the dispenser, the dosage should be doubled for the next 2 days. The regular schedule should then be resumed, but an additional method of protection must be used as backup for the next 7 days if she has sex during that time or she may become pregnant.

If two consecutive active tablets are missed in week 3 of the dispenser or three consecutive active tablets are missed during any of the first 3 weeks of the dispenser, direct the patient to do one of the following: Day 1 Starters should discard the rest of the dispenser and begin a new dispenser that same day; Sunday Starters should continue to take 1 tablet daily until Sunday, discard the rest of the dispenser and begin a new dispenser that same day. The patient may not have a period this month; however, if she has missed two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out. An additional method of protection must be used as a backup for the next 7 days after the tablets are missed if she has sex during that time or she may become pregnant.

While there is little likelihood of ovulation if only one active tablet is missed, the possibility of spotting or breakthrough bleeding is increased and should be expected if two or more successive active tablets are missed. However, the possibility of ovulation increases with each successive day that scheduled active tablets are missed.

If one or more placebo tablets of Kelnor are missed, the Kelnor schedule should be resumed on the eighth day after the last light yellow tablet was taken. Omission of placebo tablets in the 28 tablet courses does not increase the possibility of conception provided that this schedule is followed.

HOW SUPPLIED

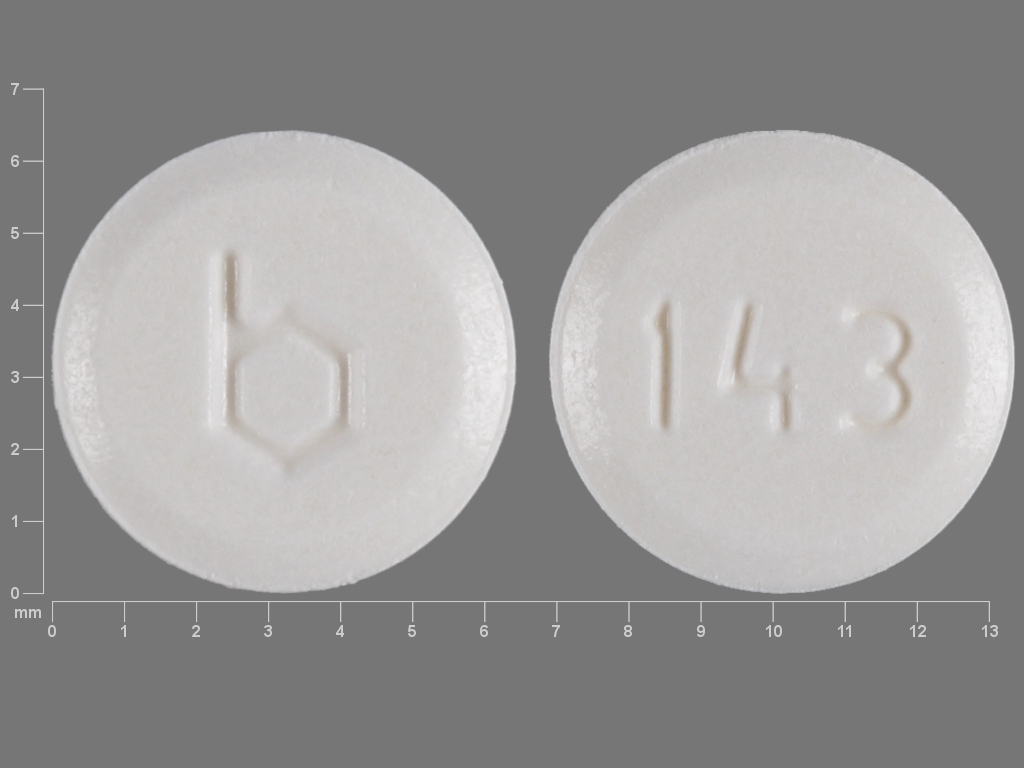

Kelnor® 1/35 (28 Day Regimen) (ethynodiol diacetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets USP) is packaged in cartons of six blister card dispensers. Each blister card dispenser contains 21 light yellow, round, flat-faced, beveled-edge, unscored tablets, debossed with stylized b on one side and 14 on the other side and 7 white, round, flat-faced, beveled-edge, unscored placebo tablets, debossed with stylized b on one side and 143 on the other side. Each light yellow tablet contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate, USP and 0.035 mg of ethinyl estradiol, USP. Each white tablet contains inert ingredients.

| Available in cartons of six blisters | NDC: 0555-9064-58 |

Store at 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature].

KEEP THIS AND ALL MEDICATIONS OUT OF THE REACH OF CHILDREN.

REFERENCES

1. Hatcher RA, et al. Contraceptive Technology: Seventeenth Revised Edition. New York, NY, 1998. 1a. Physicians' Desk Reference. 47th ed. Oradell, NJ: Medical Economics Co Inc; 1993:2598-2601. 2. Mann JI, et al. Br Med J. 1975;2(May 3):241. 3. Mann JI, et al. Br Med J. 1975;3(Sept 13):631. 4. Mann JI, et al. Br Med J. 1975;2(May 3):245. 5. Mann JI, et al. Br Med J. 1976;2(Aug 21):445. 6. Arthes FG, et al. Chest. 1976;70(Nov):574. 7. Jain AK, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;301(Oct 1):126; and Stud Fam Plann. 1977;8(March):50. 8. Ory HW. JAMA. 1977;237(June 13):2619. 9. Jick H, et al. JAMA. 1978;239(April 3):1403, 1407. 10. Jick H, et al. JAMA. 1978;240(Dec 1):2548. 11. Shapiro S, et al. Lancet. 1979;1(April 7):743. 12. Rosenberg L, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111(Jan):59. 13. Krueger DE, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111(June):655. 14. Layde P, et al. Lancet. 1981;1(March 7):541. 15. Adam SA, et al. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981;88(Aug):838. 16. Slone D, et al. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(Aug 20):420. 17. Ramcharan S, et al. The Walnut Creek Contraceptive Drug Study. Vol 3. US Govt Ptg Off; 1981; and J Reprod Med. 1980;25(Dec):346. 18. Layde PM, et al. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1983;33(Feb):75. 19. Rosenberg L, et al. JAMA. 1985;253(May 24/31):2965. 20. Mant D, et al. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987;41(Sept):215. 21. Croft P, et al. Br Med J. 1989;298(Jan 21):165. 22. Goldbaum GM, et al. JAMA. 1987;258(Sept 11):1339. 23. Bradley DD, et al. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(July 6):17. 24. Tikkanen MJ. J Reprod Med. 1986;31(Sept suppl):898. 25. Lipson A, et al. Contraception. 1986;34(Aug):121. 26. Burkman RT, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1988; 71(Jan):33. 27. Knopp RH, J Reprod Med. 1986;31(Sept suppl):913. 28. Krauss RM, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;145(Feb 15):446. 29. Wahl P, et al. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(April 14):862. 30. Wynn V, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142(March 15):766. 31. LaRosa JC. J Reprod Med. 1986;31(Sept suppl):906. 32. Wynn V, et al. J Reprod Med. 1986;31(Sept suppl):892. 33. Royal College of General Practitioners. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1967;13(May):267. 34. Inman WHW, et al. Br Med J. 1968;2(April 27):193. 35. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1968;2(April 27):199. 36. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1969;2(June 14):651. 37. Sartwell PE, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;90(Nov):365. 38. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1970;3(July 18):123. 39. Greene GR, et al. Am J Public Health. 1972;62(May):680. 40. Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Programme. Lancet. 1973;1(June 23):1399. 41. Stolley PD, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;102(Sept):197. 42. Vessey MP, et al. J Biosoc Sci. 1976;8(Oct):373. 43. Kay CR, J R Coll Gen Pract. 1978;28(July):393. 44. Petitti DB, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108(Dec):480. 45. Maguire MG, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(Aug):188. 46. Petitti DB, et al. JAMA. 1979;242(Sept 14):1150. 47. Porter JB, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59(March):299. 48. Porter JB, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(July):1. 49. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1986;292(Feb 22):526. 50. Hoover R, et al. Am J Public Health. 1978;68(April):335. 51. Vessey MP. Br J Fam Plann. 1980;6(Oct suppl):1. 52. Collaborative Group for the Study of Stroke in Young Women. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(April 26):871. 53. Royal College of General Practitioners. Oral Contraceptives and Health. New York, NY: Pitman Publ Corp; May 1974. 54. Collaborative Group for the Study of Stroke in Young Women. JAMA. 1975;231(Feb 17):718. 55. Beral V. Lancet. 1976;2(Nov 13):1047. 56. Vessey MP, et al. Lancet. 1977;2(Oct 8):731; and 1981;1(March 7):549. 57. Petitti DB, et al. Lancet. 1978;2(July 29):234. 58. Inman WHW. Br Med J. 1979;2(Dec 8):1468. 59. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1984;289(Sept 1):530. 60. Inman WHW, et al. Br Med J. 1970;2(April 25):203. 61. Meade TW, et al. Br Med J. 1980;280(May 10):1157. 62. Böttiger LE, et al. Lancet. 1980;1(May 24):1097. 63. Kay CR, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142(March 15):762. 64. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1986;292(Feb 22):526. 65. Gordon T, et al. Am J Med. 1977;62(May):707. 66. Beral V, et al. Lancet. 1977;2(Oct 8):727. 67. Ory H. Fam Plann Perspect. 1983;15(March-April):57. 68. Arthes FG, et al. Cancer. 1971;28(Dec):1391. 69. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1972;3(Sept 23):719. 70. Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. N Engl J Med. 1974;290(Jan 3):15. 71. Vessey MP, et al. Lancet. 1975;1(April 26):941. 72. Casagrande J, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;56(April):839. 73. Kelsey JL, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107(March):236. 74. Kay CR. Br Med J. 1981;282(June 27):2089. 75. Vessey MP, et al. Br Med J. 1981;282(June 27):2093. 76. The Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Center for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(Aug 14):405. 77. Paul C, et al. Br Med J. 1986; 293(Sept 20):723. 78. Miller DR, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68(Dec):863. 79. Pike MC, et al. Lancet. 1983;2(Oct 22):926. 80. McPherson K, et al. Br J Cancer. 1987;56(Nov):653. 81. Hoover R, et al. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(Aug 19):401. 82. Lees AW, et al. Int J Cancer. 1978;22(Dec):700. 83. Brinton LA, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979;62(Jan):37. 84. Black MM, Pathol Res Pract. 1980;166:491; and Cancer. 1980;46(Dec):2747; and Cancer. 1983;51(June):2147. 85. Thomas DB. JNCI. 1993;85(March 3):359. 86. Brinton LA, et al. Int J Epidemiol. 1982;11(Dec):316. 87. Harris NV, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116(Oct):643. 88. Jick H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(Nov):577. 89. McPherson K, et al. Lancet. 1983;2(Dec 17):1414. 90. Hoover R, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67(Oct):815. 91. Jick H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(Nov):586. 92. Meirik O, et al. Lancet. 1986;2(Sept 20):650. 93. Fasal E, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55(Oct):767. 94. Paffenbarger RS, et al. Cancer. 1977;39(April suppl):1887. 95. Stadel BV, et al. Contraception. 1988;38(Sept):287. 96. Miller DR, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(Feb):269. 97. Kay CR, et al. Br J Cancer. 1988;58(Nov):675. 98. Miller DR, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68(Dec):863. 99. Hulka BS, et al. Cancer. 1994;74(August 1 suppl):1111. 100. Chilvers C, et al. Lancet. 1989;1(May 6):973. 101. Huggins GR, et al. Fertil Steril. 1987;47(May):733. 102. Pike MC, et al. Br J Cancer. 1981;43(Jan):72. 103. Ory H, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124(March 15):573. 104. Stern E, et al. Science. 1977;196(June 24):1460. 105. Peritz E, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(Dec):462. 106. Ory HW, et al. In: Garattini S, Berendes H, eds. Pharmacology of Steroid Contraceptive Drugs. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1977;211-224. 107. Meisels A, et al. Cancer. 1977;40(Dec):3076. 108. Goldacre MJ, et al. Br Med J. 1978;1(March 25):748. 109. Swan SH, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139(Jan 1):52. 110. Vessey MP, et al. Lancet. 1983;2(Oct 22):930. 111. Dallenbach-Hellweg G. Pathol Res Pract. 1984;179:38. 112. Thomas DB, et al. Br Med J. 1985;290(March 30):961. 113. Brinton LA, et al. Int J Cancer. 1986;38 (Sept):339. 114. Ebeling K, et al. Int J Cancer. 1987;39(April):427. 115. Beral V, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(Dec 10):1331. 116. Baum JK, et al. Lancet. 1973;2(Oct 27):926. 117. Edmondson HA, et al. N Engl J Med. 1976;294(Feb 26):470. 118. Bein NN, et al. Br J Surg. 1977;64(June):433. 119. Klatskin G. Gastroenterology. 1977;73(Aug):386. 120. Rooks JB, et al. JAMA. 1979;242(Aug 17):644. 121. Sturtevant FM. In: Moghissi K, ed. Controversies in Contraception. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1979:93-150. 122. Henderson BE, et al. Br J Cancer. 1983;48(July):437. 123. Neuberger J, et al. Br Med J. 1986;292(May 24):1355. 124. Forman D, et al. Br Med J. 1986;292(May 24):1357. 125. La Vecchia C, et al. Br J Cancer. 1989;59(March):460. 126. Savolainen E, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140(July 1):521. 127. Ferencz C, et al. Teratology. 1980;21(April):225. 128. Rothman KJ, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(April):433. 129. Harlap S, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55(April):447. 130. Layde PM, et al. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982;36(Dec):274. 131. Rome Group for the Epidemiology and Prevention of Cholelithiasis (GREPCO). Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(May):796. 132. Strom BL, et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;39(March):335. 133. Wynn V. In: Bardin CE, et al. eds. Progesterone and Progestins. New York, NY: Raven Press;1983:395-410. 134. Perlman JA, et al. J Chron Dis. 1985;38(Oct)857. 135. Powell MG, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63(June):764. 136. Wynn V, et al. Lancet. 1966;2(Oct 1):720. 137. Fisch IR, et al. JAMA. 1977;237(June 6):2499. 138. Kay CR. Lancet. 1977;1(March 19):624. 139. Laragh JH. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126(Sept 1):141. 140. Ramcharan S. In: Garattini S, Berendes HW, eds. Pharmacology of Steroid Contraceptive Drugs. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1977:277-288. 141. Laumas KR, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98(June 1):411. 142. Saxena BN, et al. Contraception. 1977;16(Dec):605. 143. Nilsson S. et al. Contraception. 1978;17(Feb):131. 144. Washington AE, et al. JAMA. 1985;253(April 19):2246. 145. Louv WC, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(Feb):396. 146. Francis WG, et al. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;92(Jan 23):191. 147. Verhulst HL, et al. J Clin Pharmacol. 1967;7(Jan-Feb):9. 148. Ory HW. Fam Plann Perspect. 1982;14(July-Aug):182. 149. Ory HW, et al. Making Choices: Evaluating the Health Risks and Benefits of Birth Control Methods. New York, NY: The Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1983. 150. Palmer JR, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130(Nov):878. 151. Romieu I, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(Sept):1313. 152. Porter JB, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70(July):29. 153. Olsson H, et al. Cancer Detect Prev. 1991;15:265. 154. Delgado-Rodriguez M, et al. Rev Epidém Santé Publ. 1991;39:165. 155. Clavel F, et al. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20(March):32. 156. Brinton LA, et al. JNCI. 1995;87(June 7):827. 157. Thomas DB, et al. Br J Cancer. 1992;65(January):108. 158. Thomas DB, et al. Cancer Causes Cont. 1991;2(Nov):389. 159. Weinstein AL, et al. Epidemiology. 1991;2(Sept):353. 160. Ranstam J, et al. Anticancer Res. 1991;11(Nov-Dec):2043. 161. Ursin G, et al. Epidemiology. 1992;3(Sept):414. 162. White E, et al. JNCI. 1994;86(April 6):505. 163. Mann R, et al. Oral Contraceptives and Breast Cancer. Park Ridge, NJ: The Parthenon Publishing Group Inc.; 1990. 164. Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Relationship Between Oral Contraceptives and Breast Cancer. Oral Contraceptives and Breast Cancer. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991. 165. Harlap S. J Reprod Med. 1991;36(May):374. 166. Rushton L, et al. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(March):239. 167. Colditz G. Cancer. 1993;71(Feb 15 suppl):1480.

TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC.

North Wales, PA 19454

Rev. C 7/2017

BRIEF SUMMARY OF PATIENT WARNINGS

This product (like all oral contraceptives) is intended to prevent pregnancy. It does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of serious adverse effects on the heart and blood vessels from oral contraceptive use. This risk increases with age and with heavy smoking (15 or more cigarettes per day) and is quite marked in women over 35 years of age. Women who use oral contraceptives are strongly advised not to smoke.

In the detailed leaflet, "What You Should Know About Oral Contraceptives," which you have received, the risks and benefits of oral contraceptives are discussed in much more detail. That leaflet also provides information on other forms of contraception. Please take time to read it carefully for it may have been recently revised.

If you have any questions or problems regarding this information, contact your doctor.

Oral contraceptives, also known as “birth control pills” or “the pill,” are taken to prevent pregnancy and, when taken correctly, have a failure rate of about 1% per year when used without missing any pills. The typical failure rate of large numbers of pill users is less than 3% per year when women who miss pills are included. However, forgetting to take pills considerably increases the chances of pregnancy.

For most women, oral contraceptives are free of serious or unpleasant side effects. However, oral contraceptive use is associated with certain serious diseases or conditions that can cause severe disability or death, though rarely. There are some women who are at high risk of developing certain serious diseases that can be life-threatening or may cause temporary or permanent disability. The risks associated with taking oral contraceptives increase significantly if you:

- smoke, or

- have high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, or are overweight, or

- have or have had clotting disorders, heart attack, stroke, angina pectoris (chest pains on exertion), cancer of the breast or sex organs, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes), or malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous) liver tumors.

Women should not use oral contraceptives if they suspect they are pregnant or if they have unexplained vaginal bleeding.

Most side effects of the pill are not serious. The most common effects are nausea, vomiting, bleeding between menstrual periods, weight gain, breast tenderness, and difficulty wearing contact lenses. These side effects, especially nausea and vomiting, may subside within the first three months of use.

Proper use of oral contraceptives requires that they be taken under your doctor's continuing supervision, because they can be associated with serious side effects. The serious side effects of the pill occur very infrequently, especially if you are in good health and are young. However, you should know that the following medical conditions have been associated with or made worse by the pill, and that certain of the risks may persist after use of the pill has been discontinued:

- Blood clots in the legs, arms, lungs, heart (heart attack), eyes, abdomen, or elsewhere in the body. As mentioned above, smoking increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes and subsequent serious medical consequences.

- Stroke, due to a blood clot, or to bleeding in the brain (hemorrhage) as a result of bursting of a blood vessel. Stroke can lead to paralysis in all or part of the body, or to death.

- Liver tumors, which may rupture and cause severe bleeding and death. A possible, but not definite, association has also been found with the pill and liver cancer. However, with or without use of the pill, liver cancers are extremely rare in the United States.

- High blood pressure, although blood pressure ordinarily, but not always, returns to original levels when the pill is stopped.

- Gallbladder disease, which might require surgery.

The symptoms associated with these serious side effects are discussed in the detailed leaflet given to you with your supply of pills. Notify your doctor or healthcare provider if you notice any unusual physical disturbances while taking the pill. In addition, you should be aware that drugs such as antiepileptics, antibiotics (especially rifampin), as well as certain other drugs, may decrease oral contraceptive effectiveness.

There is a conflict among studies regarding breast cancer and oral contraceptive use. Some studies have reported an increase in the risk of developing breast cancer, particularly at a younger age. This increased risk appears to be related to duration of use. The majority of studies have found no overall increase in the risk of developing breast cancer. Some studies have found an increase in the incidence of cancer of the cervix in women who use oral contraceptives. However, this finding may be related to factors other than the use of oral contraceptives. There is insufficient evidence to rule out the possibility that pills may cause such cancers.

Taking the pill may provide some important non-contraceptive benefits. These include less painful menstruation, less menstrual blood loss and anemia, less risk of fibroids, pelvic infections, and noncancerous breast disease, and less risk of cancer of the ovary and of the lining of the uterus (womb).

Be sure to discuss any medical condition you may have with your healthcare provider. He or she will take a medical and family history before prescribing oral contraceptives and will also examine you. The physical examination may be delayed to another time if you request it and the healthcare provider believes that it is a good medical practice to postpone it. You should be reexamined at least once a year while taking oral contraceptives. The detailed patient information leaflet gives you further information that you should read and discuss with your healthcare provider.

DETAILED PATIENT LABELING

This product (like all oral contraceptives) is intended to prevent pregnancy. It does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

INTRODUCTION

It is important that any woman who considers using an oral contraceptive understand the risks involved. Although the oral contraceptives have important advantages over other methods of contraception, they have certain risks that no other method has. Only you and your physician can decide whether the advantages are worth these risks. This leaflet will tell you about the most important risks. It will explain how you can help your doctor prescribe the pill as safely as possible by telling him/her about yourself and being alert for the earliest signs of trouble. And it will tell you how to use the pill properly so that it will be as effective as possible. THERE IS MORE DETAILED INFORMATION AVAILABLE IN THE LEAFLET PREPARED FOR DOCTORS. Your pharmacist can show you a copy; you may need your doctor's help in understanding parts of it.

This leaflet is not a replacement for a careful discussion between you and your healthcare provider. You should discuss the information provided in this leaflet with him or her, both when you first start taking the pill and during your revisits. You should also follow your healthcare provider's advice with regard to regular check-ups while you are on the pill.

If you do not have any of the conditions listed below and are thinking about using oral contraceptives, to help you decide, you need information about the advantages and risks of oral contraceptives and of other contraceptive methods as well. This leaflet describes the advantages and risks of oral contraceptives. Except for sterilization, the intrauterine device (IUD), and abortion, which have their own specific risks, the only risks of other methods are those due to pregnancy should the method fail. Your doctor can answer questions you may have with respect to other methods of contraception, and further questions you may have on oral contraceptives after reading this leaflet.

WHAT ARE ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES?

The most common type of oral contraceptive, often simply called “the pill,” is a combination of estrogen and progestogen, the two kinds of female hormones. The amount of estrogen and progestogen can vary, but the amount of estrogen is more important because both the effectiveness and some of the dangers of the pill have been related to the amount of estrogen. The pill works principally by preventing release of an egg from the ovary during the cycle in which the pills are taken.

EFFECTIVENESS OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

The pill is one of the most effective methods of birth control. When they are taken correctly, without missing any pills, the chance of becoming pregnant is less than 1% (1 pregnancy per 100 women per year of use) when used perfectly, without missing any pills. Typical failure rates are actually about 3% per year. The chance of becoming pregnant increases with each missed pill during a menstrual cycle.

In comparison, typical failure rates for other methods of birth control during the first year of use are as follows:

|

|

|||

| % of Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy Within the First Year of Use | % of Women Continuing Use at One Year* |

||

| Method (1) | Typical Use† (2) | Perfect Use‡ (3) | (4) |

| Chance§ | 85 | 85 | |

| Spermicides¶ | 26 | 6 | 40 |

| Periodic abstinence | 25 | 63 |

|

| Calendar | 9 | ||

| Ovulation method | 3 | ||

| Sympto-thermal# | 2 | ||

| Post-ovulation | 1 | ||

| Withdrawal | 19 | 4 | |

| CapÞ | |||

| Parous women | 40 | 26 | 42 |

| Nulliparous women | 20 | 9 | 56 |

| Sponge | |||

| Parous women | 40 | 20 | 42 |

| Nulliparous women | 20 | 9 | 56 |

| DiaphragmÞ | 20 | 6 | 56 |

| Condomß | |||

| Female (Reality®) | 21 | 5 | 56 |

| Male | 14 | 3 | 61 |

| Pill | 5 | 71 |

|

| Progestin only | 0.5 | ||

| Combined | 0.1 | ||

| IUD | |||

| Progesterone T | 2 | 1.5 | 81 |

| Copper T 380A | 0.8 | 0.6 | 78 |

| LNg 20 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 81 |

| Injection (Depo-Provera®) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 70 |

| Implant (Norplant® and Norplant-2®) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 88 |

| Female sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| Male sterilization | 0.15 | 0.1 | 100 |

| Emergency Contraceptive Pills: Treatment initiated within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse reduces the risk of pregnancy by at least 75%.à |

|||

| Lactational Amenorrhea Method: LAM is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception.è |

|||

| Source: Trussell J, Contraceptive efficacy. In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Stewart F, Cates W, Stewart GK, Kowal D, Guest F, Contraceptive Technology: Seventeenth Revised Edition. New York, NY: Irvington Publishers, 1998, in press.1 |

|||

WHO SHOULD NOT TAKE ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

| Cigarette smoking increases the risk of serious adverse effects on the heart and blood vessels from oral contraceptive use. This risk increases with age and with heavy smoking (15 or more cigarettes per day) and is quite marked in women over 35 years of age. Women who use oral contraceptives are strongly advised not to smoke. |

Some women should not use the pill. For example, you should not take the pill if you are pregnant or think you may be pregnant. You should also not use the pill if you have any of the following conditions:

- Heart attack or stroke (blood clot or hemorrhage in the brain), currently or in the past.

- Blood clots in the legs (thrombophlebitis), lungs (pulmonary embolism), eyes, or elsewhere in the body, currently or in the past.

- Chest pain (angina pectoris), currently or in the past.

- Known or suspected breast cancer or cancer of the lining of the uterus (womb), cervix, or vagina, currently or in the past.

- Unexplained vaginal bleeding (until a diagnosis is reached by your doctor).

- Yellowing of the whites of the eyes or of the skin (jaundice) during pregnancy or during previous use of the pill.

- Liver tumor (whether cancerous or not), currently or in the past.

- Take any Hepatitis C drug combination containing ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir. This may increase levels of the liver enzyme “alanine aminotransferase” (ALT) in the blood.

- Known or suspected pregnancy (one or more menstrual periods missed).

Tell your healthcare provider if you have ever had any of these conditions. He or she can recommend a safer method of birth control.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS BEFORE TAKING ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Tell your healthcare provider if you have or have had any of the following conditions, as he or she will want to watch them closely or they might cause him or her to suggest using another method of contraception.

- Breast nodules (lumps), fibrocystic disease (breast cysts), abnormal mammograms (x-ray pictures of the breast), or abnormal Pap smears

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure

- High blood cholesterol or triglycerides

- Migraine or other headaches or epilepsy

- Mental depression

- Gallbladder, heart, or kidney disease

- History of scanty or irregular menstrual periods

- Problems during a prior pregnancy

- Fibroid tumors of the womb

- History of jaundice (yellowing of the whites of the eyes or of the skin)

- Varicose veins

- Tuberculosis

- Plans for elective surgery

Women with any of these conditions should be checked often by their healthcare provider if they choose to use oral contraceptives.

Also, be sure to tell your doctor if you smoke or are on any medications.

RISKS OF TAKING ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

-

Risk of developing blood clots. Blood clots and blockage of blood vessels are the most serious side effects of taking oral contraceptives. In particular, a clot in the legs can cause thrombophlebitis and a clot that travels to the lungs can cause a sudden blocking of the vessel carrying blood to the lungs. Rarely, clots occur in the blood vessels of the eye and may cause blindness, double vision, or impaired vision.

If you take oral contraceptives and need elective surgery, need to stay in bed for a prolonged illness, or have recently delivered a baby, you may be at risk of developing blood clots. You should consult your doctor about stopping oral contraceptives 3 to 4 weeks before surgery and not taking oral contraceptives for 2 weeks after surgery or during bed rest. You should also not take oral contraceptives soon after delivery of a baby. It is advisable to wait for at least 4 weeks after delivery if you are not breastfeeding. If you are breastfeeding, you should wait until you have weaned your child before using the pill. (See also the section on Breastfeeding in GENERAL PRECAUTIONS.)

The risk of circulatory disease in oral contraceptive users may be higher in users of high-dose pills and may be greater with longer duration of oral contraceptive use. In addition, some of these increased risks may continue for a number of years after stopping oral contraceptives. The risk of abnormal blood clotting increases with age in both users and nonusers of oral contraceptives, but the increased risk from the oral contraceptive appears to be present at all ages. For women aged 20 to 44 it is estimated that about 1 in 2,000 using oral contraceptives will be hospitalized each year because of abnormal clotting. Among nonusers in the same age group, about 1 in 20,000 would be hospitalized each year. For oral contraceptive users in general, it has been estimated that in women between the ages of 15 and 34, the risk of death due to a circulatory disorder is about 1 in 12,000 per year, whereas for nonusers the rate is about 1 in 50,000 per year. In the age group 35 to 44, the risk is estimated to be about 1 in 2,500 per year for oral contraceptive users and about 1 in 10,000 per year for nonusers. -

Heart attacks and strokes. Oral contraceptives may increase the tendency to develop strokes (stoppage by blood clots or rupture of blood vessels of the brain) and angina pectoris and heart attacks (blockage of blood vessels of the heart). Any of these conditions can cause death or permanent disability.

Smoking greatly increases the possibility of suffering heart attacks and strokes. Furthermore, smoking and the use of oral contraceptives greatly increases the chances of developing and dying of heart disease. - Gallbladder disease. Oral contraceptive users probably have a greater risk than nonusers of having gallbladder disease, although this risk may be related to pills containing high doses of estrogens.

- Liver tumors. In rare cases, oral contraceptives can cause benign but dangerous liver tumors. These benign tumors can rupture and cause fatal internal bleeding. In addition, a possible but not definite association has been found with the pill and liver cancers in several studies, in which a few women who developed these very rare cancers were found to have used oral contraceptives for long periods. However, liver cancers are rare.

-

Cancer of the reproductive organs and breasts. There is conflict among studies regarding breast cancer and oral contraceptive use. Some studies have reported an increase in the risk of developing breast cancer, particularly at a younger age. This increased risk appears to be related to duration of use. The majority of studies have found no overall increase in the risk of developing breast cancer. Women who use oral contraceptives and have a strong family history of breast cancer or who have had breast nodules or abnormal mammograms should be closely followed by their doctors.

Some studies have found an increase in the incidence of cancer of the cervix in women who use oral contraceptives. However, this finding may be related to factors other than the use of oral contraceptives. There is insufficient evidence to rule out the possibility that pills may cause such cancers.

ESTIMATED RISK OF DEATH FROM A BIRTH CONTROL METHOD OR PREGNANCY

All methods of birth control and pregnancy are associated with a risk of developing certain diseases that may lead to disability or death. An estimate of the number of deaths associated with different methods of birth control and pregnancy has been calculated and is shown in the following table.

ANNUAL NUMBER OF BIRTH-RELATED OR METHOD-RELATED DEATHS

ASSOCIATED WITH CONTROL OF FERTILITY PER 100,000 NONSTERILE WOMEN,

BY FERTILITY CONTROL METHOD ACCORDING TO AGE.

|

|

||||||

| Age |

||||||

| Method of Control | 15 to 19 | 20 to 24 | 25 to 29 | 30 to 34 | 35 to 39 | 40 to 44 |

| No fertility control methods* | 7 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 14.8 | 25.7 | 28.2 |

| Oral contraceptives | ||||||

| nonsmoker† | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 13.8 | 31.6 |

| smoker† | 2.2 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 13.5 | 51.1 | 117.2 |

| IUD† | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Condom* | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Diaphragm/Spermicide* | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Periodic abstinence* | 2.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

In the above table, the risk of death from any birth control method is less than the risk of childbirth, except for oral contraceptive users over the age of 35 who smoke and pill users over the age of 40 even if they do not smoke. It can be seen in the table that for women aged 15 to 39, the risk of death was highest with pregnancy (7 to 26 deaths per 100,000 women, depending on age). Among pill users who do not smoke, the risk of death was always lower than that associated with pregnancy for any age group, although over the age of 40, the risk increases to 32 deaths per 100,000 women, compared to 28 associated with pregnancy at that age. However, for pill users who smoke and are over the age of 35, the estimated number of deaths exceeds those for other methods of birth control. If a woman is over the age of 40 and smokes, her estimated risk of death is four times higher (117/100,000 women) than the estimated risk associated with pregnancy (28/100,000) in that age group.

The suggestion that women over 40 who don't smoke should not take oral contraceptives is based on information from older high-dose pills and on less selective use of pills than is practiced today. An Advisory Committee of the FDA discussed this issue in 1989 and recommended that the benefits of oral contraceptive use by healthy, nonsmoking women over 40 years of age may outweigh the possible risks. However, all women, especially older women, are cautioned to use the lowest dose pill that is effective.

WARNING SIGNALS

If any of these adverse effects occur while you are taking oral contraceptives, call your doctor immediately:

- Sharp chest pain, coughing up of blood, or sudden shortness of breath (indicating a possible blood clot in the lung)

- Pain in the calf (indicating a possible blood clot in the leg)

- Crushing chest pain or heaviness in the chest (indicating a possible heart attack)

- Sudden severe headache or vomiting, dizziness or fainting, disturbances of vision or speech, or numbness in an arm or leg (indicating a possible stroke)

- Sudden partial or complete loss of vision (indicating a possible blood clot in the blood vessels of the eye)

- Breast lumps (indicating possible breast cancer or fibrocystic disease of the breast). Ask your doctor or healthcare provider to show you how to examine your own breasts

- Severe pain or tenderness or a mass in the stomach area (indicating a possibly ruptured liver tumor)

- Difficulty in sleeping, weakness, lack of energy, fatigue, or change in mood (possibly indicating severe depression)

- Jaundice or a yellowing of the skin or eyeballs, accompanied frequently by fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, dark-colored urine, or light-colored bowel movements (indicating possible liver problems)

- Unusual swelling

- Other unusual conditions

SIDE EFFECTS OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

-

Vaginal bleeding.

Spotting. This is a slight staining between your menstrual periods that may not even require a pad. Some women spot even though they take their pills exactly as directed. Many women spot although they have never taken the pills. Spotting does not mean that your ovaries are releasing an egg. Spotting may be the result of irregular pill-taking. Getting back on schedule will usually stop it.

If you should spot while taking the pills, you should not be alarmed, because spotting usually stops by itself within a few days. It seldom occurs after the first pill cycle. Consult your doctor if spotting persists for more than a few days or if it occurs after the second cycle.

Unexpected (breakthrough) bleeding. Unexpected (breakthrough) bleeding does not mean that your ovaries have released an egg. It seldom occurs, but when it does happen it is most common in the first pill cycle. It is a flow much like a regular period, requiring the use of a pad or tampon.

If you experience breakthrough bleeding use a pad or tampon and continue with your schedule. Usually your periods will become regular within a few cycles. Breakthrough bleeding will seldom bother you again.

Consult your doctor or healthcare provider if breakthrough bleeding is heavy, does not stop within a week, or if it occurs after the second cycle. - Contact lenses. If you wear contact lenses and notice a change in vision or an inability to wear your lenses, contact your doctor or healthcare provider.

- Fluid retention or raised blood pressure. Oral contraceptives may cause edema (fluid retention), with swelling of the fingers or ankles. If you experience fluid retention, contact your doctor or healthcare provider. Some women develop high blood pressure while on the pill, which ordinarily, but not always, returns to the original levels when the pill is stopped. High blood pressure predisposes one to strokes, heart attacks, kidney disease, and other diseases of the blood vessels.

- Melasma. A spotty darkening of the skin is possible, particularly of the face. This may persist after the pill is discontinued.

- Other side effects. Other side effects may include nausea and vomiting, change in appetite, headache, nervousness, depression, dizziness, loss of scalp hair, rash, and vaginal infections.

If any of these, or other, side effects occur, call your doctor or healthcare provider.

GENERAL PRECAUTIONS

-

Missed periods and use of oral contraceptives before or during early pregnancy.

Occasionally women who are taking the pill miss periods. It has been reported to occur as frequently as several times each year in some women, depending on various factors such as age and prior history. (Your doctor is the best source of information about this.) The pill should not be used when you are pregnant or suspect you may be pregnant. Very rarely, women who are using the pill as directed become pregnant. The likelihood of becoming pregnant is higher if you occasionally miss one or two pills. Therefore, if you miss a period you should consult your physician before continuing to take the pill. If you miss a period, especially if you have not taken the pill regularly, you should use an alternative method of contraception until pregnancy has been ruled out; if you have missed more than one pill at any time, you should immediately start using an additional method of contraception and complete your pill cycle.

There is no conclusive evidence that oral contraceptive use is associated with an increase in birth defects when taken inadvertently during early pregnancy. Previously, a few studies had reported that oral contraceptives might be associated with birth defects, but these findings have not been seen in more recent studies. Nevertheless, oral contraceptives or any other drugs should not be used during pregnancy unless clearly necessary and prescribed by your doctor. You should check with your doctor about risks to your unborn child of any medication taken during pregnancy. - Breastfeeding. If you are breastfeeding, consult your doctor before starting oral contraceptives. Some of the drug will be passed on to the child in the milk. A few adverse effects on the child have been reported, including yellowing of the skin (jaundice) and breast enlargement. In addition, oral contraceptives may decrease the amount and quality of your milk. If possible, do not use oral contraceptives while breastfeeding. You should use another method of contraception since breastfeeding provides only partial protection from becoming pregnant and this partial protection decreases significantly as you breastfeed for longer periods of time. You should consider starting oral contraceptives only after you have weaned your child completely.

- Laboratory tests. If you are scheduled for any laboratory tests, tell your doctor you are taking birth control pills. Certain blood tests may be affected by birth control pills.

-

Drug interactions. Certain drugs may interact with birth control pills to make them less effective in preventing pregnancy or cause an increase in breakthrough bleeding. Such drugs include rifampin, drugs used for epilepsy such as barbiturates (for example, phenobarbital) and phenytoin (Dilantin® is one brand of this drug), phenylbutazone (Butazolidin® is one brand), Rezulin® (troglitazone) a hypoglycemic, and possibly certain antibiotics. You may need to use additional contraception when you take drugs that can make oral contraceptives less effective.

Oral contraceptives may have an influence upon the way other drugs act. Check with your doctor if you are taking any other drugs while you are on the pill.

HOW TO TAKE THE PILL