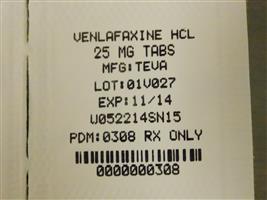

VENLAFAXINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet

Venlafaxine Hydrochloride by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Venlafaxine Hydrochloride by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Carilion Materials Management. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs

Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of venlafaxine tablets or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. Venlafaxine tablets are not approved for use in pediatric patients (see WARNINGS, Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk; PRECAUTIONS, Information for Patients; and PRECAUTIONS, Pediatric Use).

-

DESCRIPTION

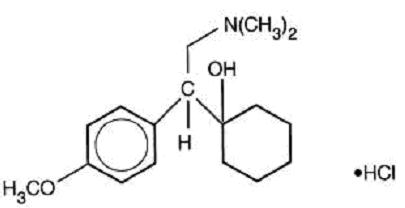

Venlafaxine hydrochloride, USP is a structurally novel antidepressant for oral administration. It is designated (R/S)-1-[2-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl] cyclohexanol hydrochloride or (±)-1-[α-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-p-methoxybenzyl]cyclohexanol hydrochloride. The structural formula is shown below.

C17H27NO2 HCl M.W. 313.87

Venlafaxine hydrochloride, USP is a white to off-white crystalline solid with a solubility of 572 mg/mL in water (adjusted to ionic strength of 0.2 M with sodium chloride). Its octanol: water (0.2 M sodium chloride) partition coefficient is 0.43.

Compressed tablets contain venlafaxine hydrochloride, USP equivalent to 25 mg, 37.5 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, or 100 mg venlafaxine. Inactive ingredients consist of colloidal silicon dioxide, ferric oxide yellow, ferric oxide red, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, and sodium starch glycolate.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacodynamics

The mechanism of the antidepressant action of venlafaxine in humans is believed to be associated with its potentiation of neurotransmitter activity in the CNS. Preclinical studies have shown that venlafaxine and its active metabolite, O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV), are potent inhibitors of neuronal serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake and weak inhibitors of dopamine reuptake. Venlafaxine and ODV have no significant affinity for muscarinic, histaminergic, or α-1 adrenergic receptors in vitro. Pharmacologic activity at these receptors is hypothesized to be associated with the various anticholinergic, sedative, and cardiovascular effects seen with other psychotropic drugs. Venlafaxine and ODV do not possess monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory activity.

Pharmacokinetics

Venlafaxine is well absorbed and extensively metabolized in the liver. O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV) is the only major active metabolite. On the basis of mass balance studies, at least 92% of a single dose of venlafaxine is absorbed. Approximately 87% of a venlafaxine dose is recovered in the urine within 48 hours as either unchanged venlafaxine (5%), unconjugated ODV (29%), conjugated ODV (26%), or other minor inactive metabolites (27%). Renal elimination of venlafaxine and its metabolites is the primary route of excretion. The relative bioavailability of venlafaxine from a tablet was 100% when compared to an oral solution. Food has no significant effect on the absorption of venlafaxine or on the formation of ODV.

The degree of binding of venlafaxine to human plasma is 27% ± 2% at concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 2215 ng/mL. The degree of ODV binding to human plasma is 30% ± 12% at concentrations ranging from 100 to 500 ng/mL. Protein-binding-induced drug interactions with venlafaxine are not expected.

Steady-state concentrations of both venlafaxine and ODV in plasma were attained within 3 days of multiple-dose therapy. Venlafaxine and ODV exhibited linear kinetics over the dose range of 75 to 450 mg total dose per day (administered on a q8h schedule). Plasma clearance, elimination half-life and steady-state volume of distribution were unaltered for both venlafaxine and ODV after multiple-dosing. Mean ± SD steady-state plasma clearance of venlafaxine and ODV is 1.3 ± 0.6 and 0.4 ± 0.2 L/h/kg, respectively; elimination half-life is 5 ± 2 and 11 ± 2 hours, respectively; and steady-state volume of distribution is 7.5 ± 3.7 L/kg and 5.7 ± 1.8 L/kg, respectively. When equal daily doses of venlafaxine were administered as either b.i.d. or t.i.d. regimens, the drug exposure (AUC) and fluctuation in plasma levels of venlafaxine and ODV were comparable following both regimens.

Age and Gender

A pharmacokinetic analysis of 404 venlafaxine-treated patients from two studies involving both b.i.d. and t.i.d. regimens showed that dose-normalized trough plasma levels of either venlafaxine or ODV were unaltered due to age or gender differences. Dosage adjustment based upon the age or gender of a patient is generally not necessary (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Liver Disease

In 9 subjects with hepatic cirrhosis, the pharmacokinetic disposition of both venlafaxine and ODV was significantly altered after oral administration of venlafaxine. Venlafaxine elimination half-life was prolonged by about 30%, and clearance decreased by about 50% in cirrhotic subjects compared to normal subjects. ODV elimination half-life was prolonged by about 60% and clearance decreased by about 30% in cirrhotic subjects compared to normal subjects. A large degree of intersubject variability was noted. Three patients with more severe cirrhosis had a more substantial decrease in venlafaxine clearance (about 90%) compared to normal subjects.

In a second study, venlafaxine was administered orally and intravenously in normal (n = 21) subjects, and in Child-Pugh A (n = 8) and Child-Pugh B (n = 11) subjects (mildly and moderately impaired, respectively). Venlafaxine oral bioavailability was increased 2 to 3 fold, oral elimination half-life was approximately twice as long and oral clearance was reduced by more than half, compared to normal subjects. In hepatically impaired subjects, ODV oral elimination half-life was prolonged by about 40%, while oral clearance for ODV was similar to that for normal subjects. A large degree of intersubject variability was noted.

Dosage adjustment is necessary in these hepatically impaired patients (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Renal Disease

In a renal impairment study, venlafaxine elimination half-life after oral administration was prolonged by about 50% and clearance was reduced by about 24% in renally impaired patients (GFR = 10 to 70 mL/min), compared to normal subjects. In dialysis patients, venlafaxine elimination half-life was prolonged by about 180% and clearance was reduced by about 57% compared to normal subjects. Similarly, ODV elimination half-life was prolonged by about 40% although clearance was unchanged in patients with renal impairment (GFR = 10 to 70 mL/min) compared to normal subjects. In dialysis patients, ODV elimination half-life was prolonged by about 142% and clearance was reduced by about 56%, compared to normal subjects. A large degree of intersubject variability was noted.

Dosage adjustment is necessary in these patients (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

CLINICAL TRIALS

The efficacy of venlafaxine hydrochloride as a treatment for major depressive disorder was established in 5 placebo-controlled, short-term trials. Four of these were 6 week trials in adult outpatients meeting DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria for major depression: two involving dose titration with venlafaxine hydrochloride in a range of 75 to 225 mg/day (t.i.d. schedule), the third involving fixed venlafaxine hydrochloride doses of 75, 225, and 375 mg/day (t.i.d. schedule), and the fourth involving doses of 25, 75, and 200 mg/day (b.i.d. schedule). The fifth was a 4 week study of adult inpatients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for major depression with melancholia whose venlafaxine hydrochloride doses were titrated in a range of 150 to 375 mg/day (t.i.d. schedule). In these 5 studies, venlafaxine hydrochloride was shown to be significantly superior to placebo on at least 2 of the following 3 measures: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (total score), Hamilton depressed mood item, and Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness rating. Doses from 75 to 225 mg/day were superior to placebo in outpatient studies and a mean dose of about 350 mg/day was effective in inpatients. Data from the 2 fixed-dose outpatient studies were suggestive of a dose-response relationship in the range of 75 to 225 mg/day. There was no suggestion of increased response with doses greater than 225 mg/day.

While there were no efficacy studies focusing specifically on an elderly population, elderly patients were included among the patients studied. Overall, approximately 2/3 of all patients in these trials were women. Exploratory analyses for age and gender effects on outcome did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of age or sex.

In one longer-term study, adult outpatients meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder who had responded during an 8 week open trial on venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules (75, 150, or 225 mg, qAM) were randomized to continuation of their same venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule dose or to placebo, for up to 26 weeks of observation for relapse. Response during the open phase was defined as a CGI Severity of Illness item score of ≤ 3 and a HAM-D-21 total score of ≤ 10 at the day 56 evaluation. Relapse during the double-blind phase was defined as follows: (1) a reappearance of major depressive disorder as defined by DSM-IV criteria and a CGI Severity of Illness item score of ≥ 4 (moderately ill), (2) 2 consecutive CGI Severity of Illness item scores of ≥ 4, or (3) a final CGI Severity of Illness item score of ≥ 4 for any patient who withdrew from the study for any reason. Patients receiving continued venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule treatment experienced significantly lower relapse rates over the subsequent 26 weeks compared with those receiving placebo.

In a second longer-term trial, adult outpatients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for major depression, recurrent type, who had responded (HAM-D-21 total score ≤ 12 at the day 56 evaluation) and continued to be improved [defined as the following criteria being met for days 56 through 180: (1) no HAM-D-21 total score ≥ 20; (2) no more than 2 HAM-D-21 total scores > 10; and (3) no single CGI Severity of Illness item score ≥ 4 (moderately ill)] during an initial 26 weeks of treatment on venlafaxine hydrochloride (100 to 200 mg/day, on a b.i.d. schedule) were randomized to continuation of their same venlafaxine hydrochloride dose or to placebo. The follow-up period to observe patients for relapse, defined as a CGI Severity of Illness item score ≥ 4, was for up to 52 weeks. Patients receiving continued venlafaxine hydrochloride treatment experienced significantly lower relapse rates over the subsequent 52 weeks compared with those receiving placebo.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Venlafaxine tablets USP are indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder.

The efficacy of venlafaxine tablets USP in the treatment of major depressive disorder was established in 6 week controlled trials of adult outpatients whose diagnoses corresponded most closely to the DSM-III or DSM-III-R category of major depression and in a 4 week controlled trial of inpatients meeting diagnostic criteria for major depression with melancholia (see CLINICAL TRIALS).

A major depressive episode implies a prominent and relatively persistent depressed or dysphoric mood that usually interferes with daily functioning (nearly every day for at least 2 weeks); it should include at least 4 of the following 8 symptoms: change in appetite, change in sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, loss of interest in usual activities or decrease in sexual drive, increased fatigue, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, slowed thinking or impaired concentration, and a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation.

The efficacy of venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules in maintaining an antidepressant response for up to 26 weeks following 8 weeks of acute treatment was demonstrated in a placebo-controlled trial. The efficacy of venlafaxine tablets USP in maintaining an antidepressant response in patients with recurrent depression who had responded and continued to be improved during an initial 26 weeks of treatment and were then followed for a period of up to 52 weeks was demonstrated in a second placebo-controlled trial (see CLINICAL TRIALS). Nevertheless, the physician who elects to use venlafaxine tablets USP/venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Hypersensitivity to venlafaxine hydrochloride or to any excipients in the formulation.

The use of MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders with venlafaxine hydrochloride or within 7 days of stopping treatment with venlafaxine hydrochloride is contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. The use of venlafaxine hydrochloride within 14 days of stopping an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders is also contraindicated (see WARNINGS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Starting venlafaxine hydrochloride in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue is also contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome (see WARNINGS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

WARNINGS

Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long standing concern, however, that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment. Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and others) showed that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18 to 24) with major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short-term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4400 patients. The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short-term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger patients for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk differences (drug vs. placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1000 patients treated) are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Age Range

Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1000 Patients Treated

Increases Compared to Placebo

< 18

14 additional cases

18 to 24

5 additional cases

Decreases Compared to Placebo

25 to 64

1 fewer case

≥ 65

6 fewer cases

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient's presenting symptoms.

If the decision has been made to discontinue treatment, medication should be tapered, as rapidly as is feasible, but with recognition that abrupt discontinuation can be associated with certain symptoms (see PRECAUTIONS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, Discontinuing Venlafaxine Tablets, for a description of the risks of discontinuation of venlafaxine tablets).

Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder or other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to healthcare providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers. Prescriptions for venlafaxine tablets should be written for the smallest quantity of tablets consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

Screening Patients for Bipolar Disorder

A major depressive episode may be the initial presentation of bipolar disorder. It is generally believed (though not established in controlled trials) that treating such an episode with an antidepressant alone may increase the likelihood of precipitation of a mixed/manic episode in patients at risk for bipolar disorder. Whether any of the symptoms described above represent such a conversion is unknown. However, prior to initiating treatment with an antidepressant, patients with depressive symptoms should be adequately screened to determine if they are at risk for bipolar disorder; such screening should include a detailed psychiatric history, including a family history of suicide, bipolar disorder, and depression. It should be noted that venlafaxine tablets are not approved for use in treating bipolar depression.

Serotonin Syndrome

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome has been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs, including venlafaxine hydrochloride, alone but particularly with concomitant use of other serotonergic drugs (including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, amphetamines, and St. John's Wort) and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin (in particular, MAOIs, both those intended to treat psychiatric disorders and also others, such as linezolid and intravenous methylene blue).

Serotonin syndrome symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, delirium, and coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, dizziness, diaphoresis, flushing, hyperthermia), neuromuscular symptoms (e.g., tremor, rigidity, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, incoordination), seizures, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Patients should be monitored for the emergence of serotonin syndrome.

The concomitant use of venlafaxine hydrochloride with MAOIs intended to treat psychiatric disorders is contraindicated. Venlafaxine hydrochloride should also not be started in a patient who is being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. All reports with methylene blue that provided information on the route of administration involved intravenous administration in the dose range of 1 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg. No reports involved the administration of methylene blue by other routes (such as oral tablets or local tissue injection) or at lower doses. There may be circumstances when it is necessary to initiate treatment with a MAOI such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue in a patient taking venlafaxine hydrochloride. Venlafaxine hydrochloride should be discontinued before initiating treatment with the MAOI (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

If concomitant use of venlafaxine hydrochloride with other serotonergic drugs, including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, buspirone, tryptophan, and St. John's Wort is clinically warranted, patients should be made aware of a potential increased risk of serotonin syndrome, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases.

Treatment with venlafaxine hydrochloride and any concomitant serotonergic agents should be discontinued immediately if the above events occur and supportive symptomatic treatment should be initiated.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma

The pupillary dilation that occurs following use of many antidepressant drugs including venlafaxine tablets may trigger an angle closure attack in a patient with anatomically narrow angles who does not have a patent iridectomy.

Sustained Hypertension

Venlafaxine treatment is associated with sustained increases in blood pressure in some patients. (1) In a premarketing study comparing three fixed doses of venlafaxine (75, 225, and 375 mg/day) and placebo, a mean increase in supine diastolic blood pressure (SDBP) of 7.2 mm Hg was seen in the 375 mg/day group at week 6 compared to essentially no changes in the 75 and 225 mg/day groups and a mean decrease in SDBP of 2.2 mm Hg in the placebo group. (2) An analysis for patients meeting criteria for sustained hypertension (defined as treatment-emergent SDBP ≥ 90 mm Hg and ≥ 10 mm Hg above baseline for 3 consecutive visits) revealed a dose-dependent increase in the incidence of sustained hypertension for venlafaxine:

Probability of Sustained Elevation in SDBP (Pool of Premarketing Venlafaxine Studies) Treatment Group

Incidence of Sustained Elevation in SDBP

Venlafaxine

< 100 mg/day

3%

101 to 200 mg/day

5%

201 to 300 mg/day

7%

> 300 mg/day

13%

Placebo

2%

An analysis of the patients with sustained hypertension and the 19 venlafaxine patients who were discontinued from treatment because of hypertension (< 1% of total venlafaxine-treated group) revealed that most of the blood pressure increases were in a modest range (10 to 15 mm Hg, SDBP). Nevertheless, sustained increases of this magnitude could have adverse consequences. Cases of elevated blood pressure requiring immediate treatment have been reported in postmarketing experience. Preexisting hypertension should be controlled before treatment with venlafaxine. It is recommended that patients receiving venlafaxine have regular monitoring of blood pressure. For patients who experience a sustained increase in blood pressure while receiving venlafaxine, either dose reduction or discontinuation should be considered.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Discontinuation of Treatment With Venlafaxine Tablets

Discontinuation symptoms have been systematically evaluated in patients taking venlafaxine, to include prospective analyses of clinical trials in Generalized Anxiety Disorder and retrospective surveys of trials in major depressive disorder. Abrupt discontinuation or dose reduction of venlafaxine at various doses has been found to be associated with the appearance of new symptoms, the frequency of which increased with increased dose level and with longer duration of treatment. Reported symptoms include agitation, anorexia, anxiety, confusion, impaired coordination and balance, diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, dysphoric mood, fasciculation, fatigue, flu-like symptoms, headaches, hypomania, insomnia, nausea, nervousness, nightmares, sensory disturbances (including shock-like electrical sensations), somnolence, sweating, tremor, vertigo, and vomiting.

During marketing of venlafaxine hydrochloride, other SNRIs (Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors), and SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), there have been spontaneous reports of adverse events occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, hypomania, tinnitus, and seizures. While these events are generally self-limiting, there have been reports of serious discontinuation symptoms.

Patients should be monitored for these symptoms when discontinuing treatment with venlafaxine hydrochloride. A gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Anxiety and Insomnia

Treatment-emergent anxiety, nervousness, and insomnia were more commonly reported for venlafaxine-treated patients compared to placebo-treated patients in a pooled analysis of short-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled depression studies:

Symptom

Venlafaxine n = 1033

Placebo n = 609

Anxiety

6%

3%

Nervousness

13%

6%

Insomnia

18%

10%

Anxiety, nervousness, and insomnia led to drug discontinuation in 2%, 2%, and 3%, respectively, of the patients treated with venlafaxine in the Phase 2 and Phase 3 depression studies.

Changes in Weight

Adult Patients

A dose-dependent weight loss was noted in patients treated with venlafaxine for several weeks. A loss of 5% or more of body weight occurred in 6% of patients treated with venlafaxine compared with 1% of patients treated with placebo and 3% of patients treated with another antidepressant. However, discontinuation for weight loss associated with venlafaxine was uncommon (0.1% of venlafaxine-treated patients in the Phase 2 and Phase 3 depression trials).

The safety and efficacy of venlafaxine therapy in combination with weight loss agents, including phentermine, have not been established. Coadministration of venlafaxine hydrochloride and weight loss agents is not recommended. Venlafaxine hydrochloride is not indicated for weight loss alone or in combination with other products.

Pediatric Patients

Weight loss has been observed in pediatric patients (ages 6 to 17) receiving venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules. In a pooled analysis of four eight-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible dose outpatient trials for major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients lost an average of 0.45 kg (n = 333), while placebo-treated patients gained an average of 0.77 kg (n = 333). More patients treated with venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules than with placebo experienced a weight loss of at least 3.5% in both the MDD and the GAD studies (18% of venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients vs. 3.6% of placebo-treated patients; p < 0.001). Weight loss was not limited to patients with treatment-emergent anorexia (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Changes in Appetite).

The risks associated with longer-term venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule use were assessed in an open-label study of children and adolescents who received venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules for up to six months. The children and adolescents in the study had increases in weight that were less than expected based on data from age- and sex-matched peers. The difference between observed weight gain and expected weight gain was larger for children (< 12 years old) than for adolescents (> 12 years old).

Changes in Height

Pediatric Patients

During the eight-week placebo-controlled GAD studies, venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients (ages 6 to 17) grew an average of 0.3 cm (n = 122), while placebo-treated patients grew an average of 1.0 cm (n = 132); p = 0.041. This difference in height increase was most notable in patients younger than twelve. During the eight-week placebo-controlled MDD studies, venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients grew an average of 0.8 cm (n = 146), while placebo-treated patients grew an average of 0.7 cm (n = 147). In the six-month open-label study, children and adolescents had height increases that were less than expected based on data from age- and sex-matched peers. The difference between observed growth rates and expected growth rates was larger for children (< 12 years old) than for adolescents (> 12 years old).

Changes in Appetite

Adult Patients

Treatment-emergent anorexia was more commonly reported for venlafaxine-treated (11%) than placebo-treated patients (2%) in the pool of short-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled depression studies.

Pediatric Patients

Decreased appetite has been observed in pediatric patients receiving venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules. In the placebo-controlled trials for GAD and MDD, 10% of patients aged 6 to 17 treated with venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules for up to eight weeks and 3% of patients treated with placebo reported treatment-emergent anorexia (decreased appetite). None of the patients receiving venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules discontinued for anorexia or weight loss.

Activation of Mania/Hypomania

During Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials, hypomania or mania occurred in 0.5% of patients treated with venlafaxine. Activation of mania/hypomania has also been reported in a small proportion of patients with major affective disorder who were treated with other marketed antidepressants. As with all antidepressants, venlafaxine hydrochloride should be used cautiously in patients with a history of mania.

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia may occur as a result of treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs, including venlafaxine hydrochloride. In many cases, this hyponatremia appears to be the result of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). Cases with serum sodium lower than 110 mmol/L have been reported. Elderly patients may be at greater risk of developing hyponatremia with SSRIs and SNRIs. Also, patients taking diuretics or who are otherwise volume depleted may be at greater risk (see PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use). Discontinuation of venlafaxine hydrochloride should be considered in patients with symptomatic hyponatremia and appropriate medical intervention should be instituted.

Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia include headache, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, weakness, and unsteadiness, which may lead to falls. Signs and symptoms associated with more severe and/or acute cases have included hallucination, syncope, seizure, coma, respiratory arrest, and death.

Seizures

During premarketing testing, seizures were reported in 0.26% (8/3082) of venlafaxine-treated patients. Most seizures (5 of 8) occurred in patients receiving doses of 150 mg/day or less. Venlafaxine hydrochloride should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures. It should be discontinued in any patient who develops seizures.

Abnormal Bleeding

SSRIs and SNRIs, including venlafaxine hydrochloride, may increase the risk of bleeding events. Concomitant use of aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may add to this risk. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding events related to SSRIs and SNRIs use have ranged from ecchymoses, hematomas, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages.

Patients should be cautioned about the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of venlafaxine hydrochloride and NSAIDs, aspirin, or other drugs that affect coagulation.

Serum Cholesterol Elevation

Clinically relevant increases in serum cholesterol were recorded in 5.3% of venlafaxine-treated patients and 0.0% of placebo-treated patients treated for at least 3 months in placebo-controlled trials (see ADVERSE REACTIONS, Laboratory Changes). Measurement of serum cholesterol levels should be considered during long-term treatment.

Interstitial Lung Disease and Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Interstitial lung disease and eosinophilic pneumonia associated with venlafaxine therapy have been rarely reported. The possibility of these adverse events should be considered in venlafaxine-treated patients who present with progressive dyspnea, cough or chest discomfort. Such patients should undergo a prompt medical evaluation, and discontinuation of venlafaxine therapy should be considered.

Use in Patients With Concomitant Illness

Clinical experience with venlafaxine hydrochloride in patients with concomitant systemic illness is limited. Caution is advised in administering venlafaxine hydrochloride to patients with diseases or conditions that could affect hemodynamic responses or metabolism.

Venlafaxine hydrochloride has not been evaluated or used to any appreciable extent in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses were systematically excluded from many clinical studies during the product's premarketing testing. Evaluation of the electrocardiograms for 769 patients who received venlafaxine hydrochloride in 4 to 6 week double-blind placebo-controlled trials, however, showed that the incidence of trial-emergent conduction abnormalities did not differ from that with placebo. The mean heart rate in venlafaxine hydrochloride-treated patients was increased relative to baseline by about 4 beats per minute.

The electrocardiograms for 357 patients who received venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules and 285 patients who received placebo in 8 to 12 week double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were analyzed. The mean change from baseline in corrected QT interval (QTc) for venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients was increased relative to that for placebo-treated patients (increase of 4.7 msec for venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules and decrease of 1.9 msec for placebo). In these same trials, the mean change from baseline in heart rate for venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule-treated patients was significantly higher than that for placebo (a mean increase of 4 beats per minute for venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules and 1 beat per minute for placebo). In a flexible-dose study, with venlafaxine hydrochloride doses in the range of 200 to 375 mg/day and mean dose greater than 300 mg/day, venlafaxine hydrochloride-treated patients had a mean increase in heart rate of 8.5 beats per minute compared with 1.7 beats per minute in the placebo group.

As increases in heart rate were observed, caution should be exercised in patients whose underlying medical conditions might be compromised by increases in heart rate (e.g., patients with hyperthyroidism, heart failure, or recent myocardial infarction), particularly when using doses of venlafaxine hydrochloride above 200 mg/day.

In patients with renal impairment (GFR = 10 to 70 mL/min) or cirrhosis of the liver, the clearances of venlafaxine and its active metabolite were decreased, thus prolonging the elimination half-lives of these substances. A lower dose may be necessary (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Venlafaxine hydrochloride, like all antidepressants, should be used with caution in such patients.

Information for Patients

Prescribers or other health professionals should inform patients, their families, and their caregivers about the benefits and risks associated with treatment with venlafaxine tablets and should counsel them in its appropriate use. A patient Medication Guide about “Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and other Serious Mental Illness, and Suicidal Thoughts or Actions” is available for venlafaxine tablets. The prescriber or health professional should instruct patients, their families, and their caregivers to read the Medication Guide and should assist them in understanding its contents. Patients should be given the opportunity to discuss the contents of the Medication Guide and to obtain answers to any questions they may have. The complete text of the Medication Guide is reprinted at the end of this document.

Patients should be advised of the following issues and asked to alert their prescriber if these occur while taking venlafaxine tablets.

Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk

Patients, their families, and their caregivers should be encouraged to be alert to the emergence of anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, mania, other unusual changes in behavior, worsening of depression, and suicidal ideation, especially early during antidepressant treatment and when the dose is adjusted up or down. Families and caregivers of patients should be advised to look for the emergence of such symptoms on a day-to-day basis, since changes may be abrupt. Such symptoms should be reported to the patient's prescriber or health professional, especially if they are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient's presenting symptoms. Symptoms such as these may be associated with an increased risk for suicidal thinking and behavior and indicate a need for very close monitoring and possibly changes in the medication.

Interference With Cognitive and Motor Performance

Clinical studies were performed to examine the effects of venlafaxine on behavioral performance of healthy individuals. The results revealed no clinically significant impairment of psychomotor, cognitive, or complex behavior performance. However, since any psychoactive drug may impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that venlafaxine hydrochloride therapy does not adversely affect their ability to engage in such activities.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Patients should be advised that taking venlafaxine can cause mild pupillary dilation, which in susceptible individuals, can lead to an episode of angle-closure glaucoma. Preexisting glaucoma is almost always open-angle glaucoma because angle-closure glaucoma, when diagnosed, can be treated definitively with iridectomy. Open-angle glaucoma is not a risk factor for angle closure glaucoma. Patients may wish to be examined to determine whether they are susceptible to angle closure, and have a prophylactic procedure (e.g., iridectomy), if they are susceptible.

Pregnancy

Patients should be advised to notify their physician if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy.

Concomitant Medication

Patients should be advised to inform their physicians if they are taking, or plan to take, any prescription or over-the-counter drugs, including herbal preparations and nutritional supplements, since there is a potential for interactions.

Patients should be cautioned about the risk of serotonin syndrome with the concomitant use of venlafaxine hydrochloride and triptans, tramadol, tryptophan supplements or other serotonergic agents (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS, Serotonin Syndrome and PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions, CNS-Active Drugs, Serotonergic Drugs).

Patients should be cautioned about the concomitant use of venlafaxine hydrochloride and NSAIDs, aspirin, warfarin, or other drugs that affect coagulation since combined use of psychotropic drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and these agents has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding (see PRECAUTIONS, Abnormal Bleeding).

Drug Interactions

As with all drugs, the potential for interaction by a variety of mechanisms is a possibility.

Alcohol

A single dose of ethanol (0.5 g/kg) had no effect on the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine or ODV when venlafaxine was administered at 150 mg/day in 15 healthy male subjects. Additionally, administration of venlafaxine in a stable regimen did not exaggerate the psychomotor and psychometric effects induced by ethanol in these same subjects when they were not receiving venlafaxine.

Cimetidine

Concomitant administration of cimetidine and venlafaxine in a steady-state study for both drugs resulted in inhibition of first-pass metabolism of venlafaxine in 18 healthy subjects. The oral clearance of venlafaxine was reduced by about 43%, and the exposure (AUC) and maximum concentration (Cmax) of the drug were increased by about 60%. However, coadministration of cimetidine had no apparent effect on the pharmacokinetics of ODV, which is present in much greater quantity in the circulation than is venlafaxine. The overall pharmacological activity of venlafaxine plus ODV is expected to increase only slightly, and no dosage adjustment should be necessary for most normal adults. However, for patients with preexisting hypertension, and for elderly patients or patients with hepatic dysfunction, the interaction associated with the concomitant use of venlafaxine and cimetidine is not known and potentially could be more pronounced. Therefore, caution is advised with such patients.

Diazepam

Under steady-state conditions for venlafaxine administered at 150 mg/day, a single 10 mg dose of diazepam did not appear to affect the pharmacokinetics of either venlafaxine or ODV in 18 healthy male subjects. Venlafaxine also did not have any effect on the pharmacokinetics of diazepam or its active metabolite, desmethyldiazepam, or affect the psychomotor and psychometric effects induced by diazepam.

Haloperidol

Venlafaxine administered under steady-state conditions at 150 mg/day in 24 healthy subjects decreased total oral-dose clearance (Cl/F) of a single 2 mg dose of haloperidol by 42%, which resulted in a 70% increase in haloperidol AUC. In addition, the haloperidol Cmax increased 88% when coadministered with venlafaxine, but the haloperidol elimination half-life (t1/2) was unchanged. The mechanism explaining this finding is unknown.

Lithium

The steady-state pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine administered at 150 mg/day were not affected when a single 600 mg oral dose of lithium was administered to 12 healthy male subjects. O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV) also was unaffected. Venlafaxine had no effect on the pharmacokinetics of lithium (see also CNS-Active Drugs, below).

Drugs Highly Bound to Plasma Protein

Venlafaxine is not highly bound to plasma proteins; therefore, administration of venlafaxine hydrochloride to a patient taking another drug that is highly protein bound should not cause increased free concentrations of the other drug.

Drugs That Interfere With Hemostasis (e.g., NSAIDs, Aspirin, and Warfarin)

Serotonin release by platelets plays an important role in hemostasis. Epidemiological studies of the case-control and cohort design that have demonstrated an association between use of psychotropic drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding have also shown that concurrent use of an NSAID or aspirin may potentiate this risk of bleeding. Altered anticoagulant effects, including increased bleeding, have been reported when SSRIs and SNRIs are coadministered with warfarin. Patients receiving warfarin therapy should be carefully monitored when venlafaxine hydrochloride is initiated or discontinued.

Drugs That Inhibit Cytochrome P450 Isoenzymes

CYP2D6 Inhibitors

In vitro and in vivo studies indicate that venlafaxine is metabolized to its active metabolite, ODV, by CYP2D6, the isoenzyme that is responsible for the genetic polymorphism seen in the metabolism of many antidepressants. Therefore, the potential exists for a drug interaction between drugs that inhibit CYP2D6-mediated metabolism and venlafaxine. However, although imipramine partially inhibited the CYP2D6-mediated metabolism of venlafaxine, resulting in higher plasma concentrations of venlafaxine and lower plasma concentrations of ODV, the total concentration of active compounds (venlafaxine plus ODV) was not affected. Additionally, in a clinical study involving CYP2D6-poor and -extensive metabolizers, the total concentration of active compounds (venlafaxine plus ODV), was similar in the two metabolizer groups. Therefore, no dosage adjustment is required when venlafaxine is coadministered with a CYP2D6 inhibitor.

Ketoconazole

A pharmacokinetic study with ketoconazole 100 mg b.i.d. with a single dose of venlafaxine 50 mg in extensive metabolizers (EM; n = 14) and 25 mg in poor metabolizers (PM; n = 6) of CYP2D6 resulted in higher plasma concentrations of both venlafaxine and O-desvenlafaxine (ODV) in most subjects following administration of ketoconazole. Venlafaxine Cmax increased by 26% in EM subjects and 48% in PM subjects. Cmax values for ODV increased by 14% and 29% in EM and PM subjects, respectively.

Venlafaxine AUC increased by 21% in EM subjects and 70% in PM subjects (range in PMs – 2% to 206%), and AUC values for ODV increased by 23% and 33% in EM and PM subjects (range in PMs – 38% to 105%) subjects, respectively. Combined AUCs of venlafaxine and ODV increased on average by approximately 23% in EMs and 53% in PMs, (range in PMs 4% to 134%).

Concomitant use of CYP3A4 inhibitors and venlafaxine may increase levels of venlafaxine and ODV. Therefore, caution is advised if a patient’s therapy includes a CYP3A4 inhibitor and venlafaxine concomitantly.

CYP3A4 Inhibitors

In vitro studies indicate that venlafaxine is likely metabolized to a minor, less active metabolite, N-desmethylvenlafaxine, by CYP3A4. Because CYP3A4 is typically a minor pathway relative to CYP2D6 in the metabolism of venlafaxine, the potential for a clinically significant drug interaction between drugs that inhibit CYP3A4-mediated metabolism and venlafaxine is small.

The concomitant use of venlafaxine with a drug treatment(s) that potently inhibits both CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, the primary metabolizing enzymes for venlafaxine, has not been studied. Therefore, caution is advised should a patient's therapy include venlafaxine and any agent(s) that produce potent simultaneous inhibition of these two enzyme systems.

Drugs Metabolized by Cytochrome P450 Isoenzymes

CYP2D6

In vitro studies indicate that venlafaxine is a relatively weak inhibitor of CYP2D6. These findings have been confirmed in a clinical drug interaction study comparing the effect of venlafaxine to that of fluoxetine on the CYP2D6-mediated metabolism of dextromethorphan to dextrorphan.

Imipramine

Venlafaxine did not affect the pharmacokinetics of imipramine and 2-OH-imipramine. However, desipramine AUC, Cmax, and Cmin increased by about 35% in the presence of venlafaxine. The 2-OH-desipramine AUCs increased by at least 2.5 fold (with venlafaxine 37.5 mg q12h) and by 4.5 fold (with venlafaxine 75 mg q12h). Imipramine did not affect the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and ODV. The clinical significance of elevated 2-OH-desipramine levels is unknown.

Metoprolol

Concomitant administration of venlafaxine (50 mg every 8 hours for 5 days) and metoprolol (100 mg every 24 hours for 5 days) to 18 healthy male subjects in a pharmacokinetic interaction study for both drugs resulted in an increase of plasma concentrations of metoprolol by approximately 30 to 40% without altering the plasma concentrations of its active metabolite, α-hydroxymetoprolol. Metoprolol did not alter the pharmacokinetic profile of venlafaxine or its active metabolite, O-desmethylvenlafaxine.

Venlafaxine appeared to reduce the blood pressure lowering effect of metoprolol in this study. The clinical relevance of this finding for hypertensive patients is unknown. Caution should be exercised with coadministration of venlafaxine and metoprolol.

Venlafaxine treatment has been associated with dose-related increases in blood pressure in some patients. It is recommended that patients receiving venlafaxine hydrochloride have regular monitoring of blood pressure (see WARNINGS).

Risperidone

Venlafaxine administered under steady-state conditions at 150 mg/day slightly inhibited the CYP2D6-mediated metabolism of risperidone (administered as a single 1 mg oral dose) to its active metabolite, 9-hydroxyrisperidone, resulting in an approximate 32% increase in risperidone AUC. However, venlafaxine coadministration did not significantly alter the pharmacokinetic profile of the total active moiety (risperidone plus 9-hydroxyrisperidone).

CYP3A4

Venlafaxine did not inhibit CYP3A4 in vitro. This finding was confirmed in vivo by clinical drug interaction studies in which venlafaxine did not inhibit the metabolism of several CYP3A4 substrates, including alprazolam, diazepam, and terfenadine.

Indinavir

In a study of 9 healthy volunteers, venlafaxine administered under steady-state conditions at 150 mg/day resulted in a 28% decrease in the AUC of a single 800 mg oral dose of indinavir and a 36% decrease in indinavir Cmax. Indinavir did not affect the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and ODV. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown.

CYP1A2

Venlafaxine did not inhibit CYP1A2 in vitro. This finding was confirmed in vivo by a clinical drug interaction study in which venlafaxine did not inhibit the metabolism of caffeine, a CYP1A2 substrate.

CNS-Active Drugs

The risk of using venlafaxine in combination with other CNS-active drugs has not been systematically evaluated (except in the case of those CNS-active drugs noted above). Consequently, caution is advised if the concomitant administration of venlafaxine and such drugs is required (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS).

Serotonergic Drugs

Based on the mechanism of action of SNRIs and SSRIs, including venlafaxine hydrochloride, and the potential for serotonin syndrome, caution is advised when venlafaxine is coadministered with other drugs that may affect the serotonergic neurotransmitter systems, such as triptans, lithium, fentanyl, tramadol, amphetamines, or St. John’s Wort (see WARNINGS, Serotonin Syndrome). If concomitant treatment of venlafaxine with these drugs is clinically warranted, careful observation of the patient is advised, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS, Serotonin Syndrome). The concomitant use of venlafaxine with tryptophan supplements is not recommended (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS, Serotonin Syndrome).

Triptans

There have been rare postmarketing reports of serotonin syndrome with use of an SSRI and a triptan. If concomitant treatment of venlafaxine with a triptan is clinically warranted, careful observation of the patient is advised, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases (see WARNINGS, Serotonin Syndrome).

Drug-Laboratory Test Interactions

False-positive urine immunoassay screening tests for phencyclidine (PCP) and amphetamine have been reported in patients taking venlafaxine. This is due to lack of specificity of the screening tests. False positive test results may be expected for several days following discontinuation of venlafaxine therapy. Confirmatory tests, such as gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, will distinguish venlafaxine from PCP and amphetamine.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Venlafaxine was given by oral gavage to mice for 18 months at doses up to 120 mg/kg per day, which was 16 times, on a mg/kg basis, and 1.7 times on a mg/m2 basis, the maximum recommended human dose. Venlafaxine was also given to rats by oral gavage for 24 months at doses up to 120 mg/kg per day. In rats receiving the 120 mg/kg dose, plasma levels of venlafaxine were 1 times (male rats) and 6 times (female rats) the plasma levels of patients receiving the maximum recommended human dose. Plasma levels of the O-desmethyl metabolite were lower in rats than in patients receiving the maximum recommended dose. Tumors were not increased by venlafaxine treatment in mice or rats.

Mutagenicity

Venlafaxine and the major human metabolite, O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV), were not mutagenic in the Ames reverse mutation assay in Salmonella bacteria or the CHO/HGPRT mammalian cell forward gene mutation assay. Venlafaxine was also not mutagenic in the in vitro BALB/c-3T3 mouse cell transformation assay, the sister chromatid exchange assay in cultured CHO cells, or the in vivo chromosomal aberration assay in rat bone marrow. ODV was not mutagenic in the in vitro CHO cell chromosomal aberration assay. There was a clastogenic response in the in vivo chromosomal aberration assay in rat bone marrow in male rats receiving 200 times, on a mg/kg basis, or 50 times, on a mg/m2 basis, the maximum human daily dose. The no effect dose was 67 times (mg/kg) or 17 times (mg/m2) the human dose.

Impairment of Fertility

Reproduction and fertility studies of venlafaxine in rats showed no adverse effects on male or female fertility at oral doses of up to 2 times the maximum recommended human dose of 225 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis.

However, reduced fertility was observed in a study in which male and female rats were treated with O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV), the major human metabolite of venlafaxine, prior to and during mating and gestation. This occurred at an ODV exposure (AUC) approximately 2 to 3 times that associated with a human venlafaxine dose of 225 mg/day.

Pregnancy

Teratogenic Effects

Pregnancy Category C

Venlafaxine did not cause malformations in offspring of rats or rabbits given doses up to 11 times (rat) or 12 times (rabbit) the maximum recommended human daily dose on a mg/kg basis, or 2.5 times (rat) and 4 times (rabbit) the human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis. However, in rats, there was a decrease in pup weight, an increase in stillborn pups, and an increase in pup deaths during the first 5 days of lactation, when dosing began during pregnancy and continued until weaning. The cause of these deaths is not known. These effects occurred at 10 times (mg/kg) or 2.5 times (mg/m2) the maximum human daily dose. The no effect dose for rat pup mortality was 1.4 times the human dose on a mg/kg basis or 0.25 times the human dose on a mg/m2 basis. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, this drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

Nonteratogenic Effects

Neonates exposed to venlafaxine hydrochloride, other SNRIs (Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors), or SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. Such complications can arise immediately upon delivery. Reported clinical findings have included respiratory distress, cyanosis, apnea, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremor, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These features are consistent with either a direct toxic effect of SSRIs and SNRIs or, possibly, a drug discontinuation syndrome. It should be noted that, in some cases, the clinical picture is consistent with serotonin syndrome (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions, CNS-Active Drugs). When treating a pregnant woman with venlafaxine hydrochloride during the third trimester, the physician should carefully consider the potential risks and benefits of treatment (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Labor and Delivery

The effect of venlafaxine hydrochloride on labor and delivery in humans is unknown.

Nursing Mothers

Venlafaxine and ODV have been reported to be excreted in human milk. Because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants from venlafaxine hydrochloride, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in the pediatric population have not been established (see BOX WARNING and WARNINGS, Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk). Two placebo-controlled trials in 766 pediatric patients with MDD and two placebo-controlled trials in 793 pediatric patients with GAD have been conducted with venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules, and the data were not sufficient to support a claim for use in pediatric patients.

Anyone considering the use of venlafaxine tablets in a child or adolescent must balance the potential risks with the clinical need.

Although no studies have been designed to primarily assess venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule’s impact on the growth, development, and maturation of children and adolescents, the studies that have been done suggest that venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules may adversely affect weight and height (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Changes in Height and Changes in Weight). Should the decision be made to treat a pediatric patient with venlafaxine hydrochloride, regular monitoring of weight and height is recommended during treatment, particularly if it is to be continued long term. The safety of venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsule treatment for pediatric patients has not been systematically assessed for chronic treatment longer than six months in duration.

In the studies conducted in pediatric patients (ages 6 to 17), the occurrence of blood pressure and cholesterol increases considered to be clinically relevant in pediatric patients was similar to that observed in adult patients. Consequently, the precautions for adults apply to pediatric patients (see WARNINGS, Sustained Hypertension and PRECAUTIONS, General, Serum Cholesterol Elevation).

Geriatric Use

Of the 2,897 patients in Phase 2 and Phase 3 depression studies with venlafaxine hydrochloride, 12% (357) were 65 years of age or over. No overall differences in effectiveness or safety were observed between these patients and younger patients, and other reported clinical experience generally has not identified differences in response between the elderly and younger patients. However, greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out. SSRIs and SNRIs, including venlafaxine hydrochloride, have been associated with cases of clinically significant hyponatremia in elderly patients, who may be at greater risk for this adverse event (see PRECAUTIONS, Hyponatremia).

The pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and ODV are not substantially altered in the elderly (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). No dose adjustment is recommended for the elderly on the basis of age alone, although other clinical circumstances, some of which may be more common in the elderly, such as renal or hepatic impairment, may warrant a dose reduction (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Associated With Discontinuation of Treatment

Nineteen percent (537/2897) of venlafaxine patients in Phase 2 and Phase 3 depression studies discontinued treatment due to an adverse event. The more common events (≥ 1%) associated with discontinuation and considered to be drug-related (i.e., those events associated with dropout at a rate approximately twice or greater for venlafaxine compared to placebo) included:

Incidence in Controlled Trials

Commonly Observed Adverse Events in Controlled Clinical Trials

The most commonly observed adverse events associated with the use of venlafaxine hydrochloride (incidence of 5% or greater) and not seen at an equivalent incidence among placebo-treated patients (i.e., incidence for venlafaxine hydrochloride at least twice that for placebo), derived from the 1% incidence table below, were asthenia, sweating, nausea, constipation, anorexia, vomiting, somnolence, dry mouth, dizziness, nervousness, anxiety, tremor, and blurred vision as well as abnormal ejaculation/orgasm and impotence in men.

Adverse Events Occurring at an Incidence of 1% or More Among Venlafaxine Hydrochloride-Treated Patients

The table that follows enumerates adverse events that occurred at an incidence of 1% or more, and were more frequent than in the placebo group, among venlafaxine hydrochloride-treated patients who participated in short-term (4 to 8 week) placebo-controlled trials in which patients were administered doses in a range of 75 to 375 mg/day. This table shows the percentage of patients in each group who had at least one episode of an event at some time during their treatment. Reported adverse events were classified using a standard COSTART-based Dictionary terminology.

The prescriber should be aware that these figures cannot be used to predict the incidence of side effects in the course of usual medical practice where patient characteristics and other factors differ from those which prevailed in the clinical trials. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be compared with figures obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses and investigators. The cited figures, however, do provide the prescribing physician with some basis for estimating the relative contribution of drug and nondrug factors to the side effect incidence rate in the population studied.

TABLE 2: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Experience Incidence in 4 to 8 Week Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials* — Incidence less than 1%. - * Events reported by at least 1% of patients treated with venlafaxine hydrochloride are included, and are rounded to the nearest %. Events for which the venlafaxine hydrochloride incidence was equal to or less than placebo are not listed in the table, but included the following: abdominal pain, pain, back pain, flu syndrome, fever, palpitation, increased appetite, myalgia, arthralgia, amnesia, hypesthesia, rhinitis, pharyngitis, sinusitis, cough increased, and dysmenorrhea3.

- † Incidence based on number of male patients.

- ‡ Incidence based on number of female patients.

Body System

Preferred Term

Venlafaxine Hydrochloride (n = 1033)

Placebo (n = 609)

Body as a Whole

Headache

25%

24%

Asthenia

12%

6%

Infection

6%

5%

Chills

3%

—

Chest pain

2%

1%

Trauma

2%

1%

Cardiovascular

Vasodilatation

4%

3%

Increased blood pressure/hypertension

2%

—

Tachycardia

2%

—

Postural hypotension

1%

—

Dermatological

Sweating

12%

3%

Rash

3%

2%

Pruritus

1%

—

Gastrointestinal

Nausea

37%

11%

Constipation

15%

7%

Anorexia

11%

2%

Diarrhea

8%

7%

Vomiting

6%

2%

Dyspepsia

5%

4%

Flatulence

3%

2%

Metabolic

Weight loss

1%

—

Nervous System

Somnolence

23%

9%

Dry mouth

22%

11%

Dizziness

19%

7%

Insomnia

18%

10%

Nervousness

13%

6%

Anxiety

6%

3%

Tremor

5%

1%

Abnormal dreams

4%

3%

Hypertonia

3%

2%

Paresthesia

3%

2%

Libido decreased

2%

—

Agitation

2%

—

Confusion

2%

1%

Thinking abnormal

2%

1%

Depersonalization

1%

—

Depression

1%

—

Urinary retention

1%

—

Twitching

1%

—

Respiration

Yawn

3%

—

Special Senses

Blurred vision

6%

2%

Taste perversion

2%

—

Tinnitus

2%

—

Mydriasis

2%

—

Urogenital System

Abnormal ejaculation/orgasm

12%†

—†

Impotence

6%†

—†

Urinary frequency

3%

2%

Urination impaired

2%

—

Orgasm disturbance

2%‡

—‡

Dose Dependency of Adverse Events

A comparison of adverse event rates in a fixed-dose study comparing venlafaxine hydrochloride 75, 225, and 375 mg/day with placebo revealed a dose dependency for some of the more common adverse events associated with venlafaxine hydrochloride use, as shown in the table that follows. The rule for including events was to enumerate those that occurred at an incidence of 5% or more for at least one of the venlafaxine groups and for which the incidence was at least twice the placebo incidence for at least one venlafaxine hydrochloride group. Tests for potential dose relationships for these events (Cochran-Armitage Test, with a criterion of exact 2 sided p-value ≤ 0.05) suggested a dose-dependency for several adverse events in this list, including chills, hypertension, anorexia, nausea, agitation, dizziness, somnolence, tremor, yawning, sweating, and abnormal ejaculation.

TABLE 3: Treatment-Emergent Adverse Experience Incidence in a Dose Comparison Trial Venlafaxine Hydrochloride (mg/day)

Body System/Preferred Term

Placebo (n = 92)

75 (n = 89)

225 (n = 89)

375 (n = 88)

Body as a Whole

Abdominal pain

3.3%

3.4%

2.2%

8%

Asthenia

3.3%

16.9%

14.6%

14.8%

Chills

1.1%

2.2%

5.6%

6.8%

Infection

2.2%

2.2%

5.6%

2.3%

Cardiovascular System

Hypertension

1.1%

1.1%

2.2%

4.5%

Vasodilatation

0%

4.5%

5.6%

2.3%

Digestive System

Anorexia

2.2%

14.6%

13.5%

17%

Dyspepsia

2.2%

6.7%

6.7%

4.5%

Nausea

14.1%

32.6%

38.2%

58%

Vomiting

1.1%

7.9%

3.4%

6.8%

Nervous System

Agitation

0%

1.1%

2.2%

4.5%

Anxiety

4.3%

11.2%

4.5%

2.3%

Dizziness

4.3%

19.1%

22.5%

23.9%

Insomnia

9.8%

22.5%

20.2%

13.6%

Libido decreased

1.1%

2.2%

1.1%

5.7%

Nervousness

4.3%

21.3%

13.5%

12.5%

Somnolence

4.3%

16.9%

18.0%

26.1%

Tremor

0%

1.1%

2.2%

10.2%

Respiratory System

Yawn

0%

4.5%

5.6%

8%

Skin and Appendages

Sweating

5.4%

6.7%

12.4%

19.3%

Special Senses

Abnormality of accommodation

0%

9.1%

7.9%

5.6%

Urogenital System

Abnormal ejaculation/orgasm

0%

4.5%

2.2%

12.5%

Impotence

0%

5.8%

2.1%

3.6%

(Number of men)

(n = 63)

(n = 52)

(n = 48)

(n = 56)

Adaptation to Certain Adverse Events

Over a 6 week period, there was evidence of adaptation to some adverse events with continued therapy (e.g., dizziness and nausea), but less to other effects (e.g., abnormal ejaculation and dry mouth).

Vital Sign Changes

Venlafaxine hydrochloride treatment (averaged over all dose groups) in clinical trials was associated with a mean increase in pulse rate of approximately 3 beats per minute, compared to no change for placebo. In a flexible-dose study, with doses in the range of 200 to 375 mg/day and mean dose greater than 300 mg/day, the mean pulse was increased by about 2 beats per minute compared with a decrease of about 1 beat per minute for placebo.

In controlled clinical trials, venlafaxine hydrochloride was associated with mean increases in diastolic blood pressure ranging from 0.7 to 2.5 mm Hg averaged over all dose groups, compared to mean decreases ranging from 0.9 to 3.8 mm Hg for placebo. However, there is a dose dependency for blood pressure increase (see WARNINGS).

Laboratory Changes

Of the serum chemistry and hematology parameters monitored during clinical trials with venlafaxine hydrochloride, a statistically significant difference with placebo was seen only for serum cholesterol. In premarketing trials, treatment with venlafaxine tablets was associated with a mean final on-therapy increase in total cholesterol of 3 mg/dL.

Patients treated with venlafaxine tablets for at least 3 months in placebo-controlled 12 month extension trials had a mean final on-therapy increase in total cholesterol of 9.1 mg/dL compared with a decrease of 7.1 mg/dL among placebo-treated patients. This increase was duration dependent over the study period and tended to be greater with higher doses. Clinically relevant increases in serum cholesterol, defined as 1) a final on-therapy increase in serum cholesterol ≥ 50 mg/dL from baseline and to a value ≥ 261 mg/dL or 2) an average on-therapy increase in serum cholesterol ≥ 50 mg/dL from baseline and to a value ≥ 261 mg/dL, were recorded in 5.3% of venlafaxine-treated patients and 0% of placebo-treated patients (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Serum Cholesterol Elevation).

ECG Changes

In an analysis of ECGs obtained in 769 patients treated with venlafaxine hydrochloride and 450 patients treated with placebo in controlled clinical trials, the only statistically significant difference observed was for heart rate, i.e., a mean increase from baseline of 4 beats per minute for venlafaxine hydrochloride. In a flexible-dose study, with doses in the range of 200 to 375 mg/day and mean dose greater than 300 mg/day, the mean change in heart rate was 8.5 beats per minute compared with 1.7 beats per minute for placebo (see PRECAUTIONS, General, Use in Patients With Concomitant Illness).

Other Events Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Venlafaxine

During its premarketing assessment, multiple doses of venlafaxine hydrochloride were administered to 2897 patients in Phase 2 and Phase 3 studies. In addition, in premarketing assessment of venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules, multiple doses were administered to 705 patients in Phase 3 major depressive disorder studies and venlafaxine hydrochloride was administered to 96 patients. During its premarketing assessment, multiple doses of venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release capsules were also administered to 1381 patients in Phase 3 GAD studies and 277 patients in Phase 3 Social Anxiety Disorder studies. The conditions and duration of exposure to venlafaxine in both development programs varied greatly, and included (in overlapping categories) open and double-blind studies, uncontrolled and controlled studies, inpatient (venlafaxine hydrochloride only) and outpatient studies, fixed-dose and titration studies. Untoward events associated with this exposure were recorded by clinical investigators using terminology of their own choosing. Consequently, it is not possible to provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing adverse events without first grouping similar types of untoward events into a smaller number of standardized event categories.

In the tabulations that follow, reported adverse events were classified using a standard COSTART-based Dictionary terminology. The frequencies presented, therefore, represent the proportion of the 5356 patients exposed to multiple doses of either formulation of venlafaxine who experienced an event of the type cited on at least one occasion while receiving venlafaxine. All reported events are included except those already listed in TABLE 2 and those events for which a drug cause was remote. If the COSTART term for an event was so general as to be uninformative, it was replaced with a more informative term. It is important to emphasize that, although the events reported occurred during treatment with venlafaxine, they were not necessarily caused by it.

Events are further categorized by body system and listed in order of decreasing frequency using the following definitions: frequent adverse events are defined as those occurring on one or more occasions in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse events are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare events are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Body as a whole—Frequent: accidental injury, chest pain substernal, neck pain; Infrequent: face edema, intentional injury, malaise, moniliasis, neck rigidity, pelvic pain, photosensitivity reaction, suicide attempt, withdrawal syndrome; Rare: appendicitis, bacteremia, carcinoma, cellulitis.

Cardiovascular system—Frequent: migraine; Infrequent: angina pectoris, arrhythmia, extrasystoles, hypotension, peripheral vascular disorder (mainly cold feet and/or cold hands), syncope, thrombophlebitis; Rare: aortic aneurysm, arteritis, first-degree atrioventricular block, bigeminy, bradycardia, bundle branch block, capillary fragility, cardiovascular disorder (mitral valve and circulatory disturbance), cerebral ischemia, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, heart arrest, mucocutaneous hemorrhage, myocardial infarct, pallor.

Digestive system—Frequent: eructation; Infrequent: bruxism, colitis, dysphagia, tongue edema, esophagitis, gastritis, gastroenteritis, gastrointestinal ulcer, gingivitis, glossitis, rectal hemorrhage, hemorrhoids, melena, oral moniliasis, stomatitis, mouth ulceration; Rare: cheilitis, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, duodenitis, esophageal spasm, hematemesis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gum hemorrhage, hepatitis, ileitis, jaundice, intestinal obstruction, parotitis, periodontitis, proctitis, increased salivation, soft stools, tongue discoloration.

Endocrine system—Rare: goiter, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, thyroid nodule, thyroiditis.

Hemic and lymphatic system—Frequent: ecchymosis; Infrequent: anemia, leukocytosis, leukopenia, lymphadenopathy, thrombocythemia, thrombocytopenia; Rare: basophilia, bleeding time increased, cyanosis, eosinophilia, lymphocytosis, multiple myeloma, purpura.

Metabolic and nutritional—Frequent: edema, weight gain; Infrequent: alkaline phosphatase increased, dehydration, hypercholesteremia, hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, hypokalemia, SGOT (AST) increased, SGPT (ALT) increased, thirst; Rare: alcohol intolerance, bilirubinemia, BUN increased, creatinine increased, diabetes mellitus, glycosuria, gout, healing abnormal, hemochromatosis, hypercalcinuria, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperuricemia, hypocholesteremia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, hypoproteinemia, uremia.

Musculoskeletal system—Infrequent: arthritis, arthrosis, bone pain, bone spurs, bursitis, leg cramps, myasthenia, tenosynovitis; Rare: pathological fracture, myopathy, osteoporosis, osteosclerosis, plantar fasciitis, rheumatoid arthritis, tendon rupture.

Nervous system—Frequent: trismus, vertigo; Infrequent: akathisia, apathy, ataxia, circumoral paresthesia, CNS stimulation, emotional lability, euphoria, hallucinations, hostility, hyperesthesia, hyperkinesia, hypotonia, incoordination, libido increased, manic reaction, myoclonus, neuralgia, neuropathy, psychosis, seizure, abnormal speech, stupor; Rare: akinesia, alcohol abuse, aphasia, bradykinesia, buccoglossal syndrome, cerebrovascular accident, loss of consciousness, delusions, dementia, dystonia, facial paralysis, feeling drunk, abnormal gait, Guillain-Barre syndrome, hyperchlorhydria, hypokinesia, impulse control difficulties, neuritis, nystagmus, paranoid reaction, paresis, psychotic depression, reflexes decreased, reflexes increased, suicidal ideation, torticollis.

Respiratory system—Frequent: bronchitis, dyspnea; Infrequent: asthma, chest congestion, epistaxis, hyperventilation, laryngismus, laryngitis, pneumonia, voice alteration; Rare: atelectasis, hemoptysis, hypoventilation, hypoxia, larynx edema, pleurisy, pulmonary embolus, sleep apnea.