ENALAPRIL MALEATE tablet

ENALAPRIL MALEATE by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

ENALAPRIL MALEATE by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by State of Florida DOH Central Pharmacy, Sandhills Packaging. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

Product Information

ENALAPRIL MALEATE TABLETS, USP

Rx onlyUSE IN PREGNANCY

When used in pregnancy during the second and third trimesters, ACE inhibitors can cause injury and even death to the developing fetus. When pregnancy is detected, enalapril maleate should be discontinued as soon as possible. See WARNINGS, Fetal / Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality.

-

DESCRIPTION

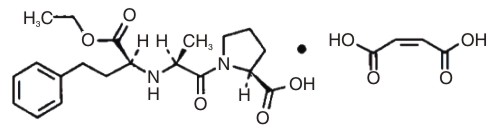

Enalapril maleate is the maleate salt of enalapril, the ethyl ester of a long-acting angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, enalaprilat. Enalapril maleate is chemically described as L-Proline,1-[N-[1-(ethoxycarbonyl)-3-phenylpropyl]-L-alanyl]- , (S)-, (Z)-2-butenedioate (1:1). Its molecular formula is, C20H28N2O5·C4H4O4, and its structural formula is:Enalapril maleate is a white to off-white, crystalline powder with a molecular weight of 492.53. It is sparingly soluble in water, soluble in ethanol, and freely soluble in methanol.

Enalapril is a pro-drug; following oral administration, it is bioactivated by hydrolysis of the ethyl ester to enalaprilat, which is the active angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.

Enalapril maleate is supplied as 2.5 mg, 5 mg,10 mg and 20 mg tablets for oral administration. In addition, each tablet contains the following inactive ingredients: hypromellose, anhydrous lactose, corn starch, stearic acid and talc. The 10 mg and 20 mg tablets also contain iron oxides. -

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

Enalapril, after hydrolysis to enalaprilat, inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in human subjects and animals. ACE is a peptidyl dipeptidase that catalyzes the conversion of angiotensin I to the vasoconstrictor substance, angiotensin II. Angiotensin II also stimulates aldosterone secretion by the adrenal cortex. The beneficial effects of enalapril in hypertension and heart failure appear to result primarily from suppression of the renin -angiotensin-aldosterone system. Inhibition of ACE results in decreased plasma angiotensin II, which leads to decreased vasopressor activity and to decreased aldosterone secretion. Although the latter decrease is small, it results in small increases of serum potassium. In hypertensive patients treated with enalapril alone for up to 48 weeks, mean increases in serum potassium of approximately 0.2 mEq/L were observed. In patients treated with enalapril plus a thiazide diuretic, there was essentially no change in serum potassium. (See PRECAUTIONS.) Removal of angiotensin II negative feedback on renin secretion leads to increased plasma renin activity.

ACE is identical to kininase, an enzyme that degrades bradykinin. Whether increased levels of bradykinin, a potent vasodepressor peptide, play a role in the therapeutic effects of enalapril remains to be elucidated.

While the mechanism through which enalapril lowers blood pressure is believed to be primarily suppression of the renin-angiotensin- aldosterone system, enalapril is antihypertensive even in patients with low-renin hypertension. Although enalapril was antihypertensive in all races studied, black hypertensive patients (usually a low-renin hypertensive population) had a smaller average response to enalapril monotherapy than non-black patients.Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

Following oral administration of enalapril maleate, peak serum concentrations of enalapril occur within about one hour. Based on urinary recovery, the extent of absorption of enalapril is approximately 60 percent. Enalapril absorption is not influenced by the presence of food in the gastrointestinal tract. Following absorption, enalapril is hydrolyzed to enalaprilat, which is a more potent angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor than enalapril; enalaprilat is poorly absorbed when administered orally. Peak serum concentrations of enalaprilat occur three to four hours after an oral dose of enalapril maleate. Excretion of enalapril is primarily renal. Approximately 94 percent of the dose is recovered in the urine and feces as enalaprilat or enalapril. The principal components in urine are enalaprilat, accounting for about 40 percent of the dose, and intact enalapril. There is no evidence of metabolites of enalapril, other than enalaprilat.

The serum concentration profile of enalaprilat exhibits a prolonged terminal phase, apparently representing a small fraction of the administered dose that has been bound to ACE. The amount bound does not increase with dose, indicating a saturable site of binding. The effective half-life for accumulation of enalaprilat following multiple doses of enalapril maleate is 11 hours.

The disposition of enalapril and enalaprilat in patients with renal insufficiency is similar to that in patients with normal renal function until the glomerular filtration rate is 30 mL/min or less. With glomerular filtration rate ≤30 mL/min, peak and trough enalaprilat levels increase, time to peak concentration increases and time to steady state may be delayed. The effective half-life of enalaprilat following multiple doses of enalapril maleate is prolonged at this level of renal insufficiency. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.) Enalaprilat is dialyzable at the rate of 62 mL/min.

Studies in dogs indicate that enalapril crosses the blood-brain barrier poorly, if at all; enalaprilat does not enter the brain. Multiple doses of enalapril maleate in rats do not result in accumulation in any tissues. Milk of lactating rats contains radioactivity following administration of 14C-enalapril maleate. Radioactivity was found to cross the placenta following administration of labeled drug to pregnant hamsters.Pharmacodynamics and Clinical Effects

Hypertension: Administration of enalapril to patients with hypertension of severity ranging from mild to severe results in a reduction of both supine and standing blood pressure usually with no orthostatic component. Symptomatic postural hypotension is therefore infrequent, although it might be anticipated in volume-depleted patients. (See WARNINGS.)

In most patients studied, after oral administration of a single dose of enalapril, onset of antihypertensive activity was seen at one hour with peak reduction of blood pressure achieved by four to six hours.

At recommended doses, antihypertensive effects have been maintained for at least 24 hours. In some patients the effects may diminish toward the end of the dosing interval (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

In some patients achievement of optimal blood pressure reduction may require several weeks of therapy.

The antihypertensive effects of enalapril have continued during long term therapy. Abrupt withdrawal of enalapril has not been associated with a rapid increase in blood pressure.

In hemodynamic studies in patients with essential hypertension, blood pressure reduction was accompanied by a reduction in peripheral arterial resistance with an increase in cardiac output and little or no change in heart rate. Following administration of enalapril, there is an increase in renal blood flow; glomerular filtration rate is usually unchanged. The effects appear to be similar in patients with renovascular hypertension.

When given together with thiazide-type diuretics, the blood pressure lowering effects of enalapril are approximately additive.

In a clinical pharmacology study, indomethacin or sulindac was administered to hypertensive patients receiving enalapril. In this study there was no evidence of a blunting of the antihypertensive action of enalapril. (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.)

Heart Failure: In trials in patients treated with digitalis and diuretics, treatment with enalapril resulted in decreased systemic vascular resistance, blood pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and heart size, and increased cardiac output and exercise tolerance. Heart rate was unchanged or slightly reduced, and mean ejection fraction was unchanged or increased. There was a beneficial effect on severity of heart failure as measured by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and on symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue. Hemodynamic effects were observed after the first dose, and appeared to be maintained in uncontrolled studies lasting as long as four months. Effects on exercise tolerance, heart size, and severity and symptoms of heart failure were observed in placebo-controlled studies lasting from eight weeks to over one year.

Heart Failure, Mortality Trials: In a multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 2,569 patients with all degrees of symptomatic heart failure and ejection fraction ≤ 35 percent were randomized to placebo or enalapril and followed for up to 55 months (Solvd-Treatment). Use of enalapril was associated with an 11 percent reduction in all-cause mortality and a 30 percent reduction in hospitalization for heart failure. Diseases that excluded patients from enrollment in the study included severe stable angina (>2 attacks/day), hemodynamically significant valvular or outflow tract obstruction, renal failure (creatinine >2.5 mg/dL), cerebral vascular disease (e.g., significant carotid artery disease), advanced pulmonary disease, malignancies, active myocarditis and constrictive pericarditis. The mortality benefit associated with enalapril does not appear to depend upon digitalis being present.

A second multicenter trial used the SOLVD protocol for study of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients. SOLVDPrevention patients, who had left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35% and no history of symptomatic heart failure, were randomized to placebo (n=2117) or enalapril (n=2111) and followed for up to 5 years. The majority of patients in the SOLVD-Prevention trial had a history of ischemic heart disease. A history of myocardial infarction was present in 80 percent of patients, current angina pectoris in 34 percent, and a history of hypertension in 37 percent. No statistically significant mortality effect was demonstrated in this population. Enalapril-treated subjects had 32% fewer first hospitalizations for heart failure, and 32% fewer total heart failure hospitalizations. Compared to placebo, 32 percent fewer patients receiving enalapril developed symptoms of overt heart failure. Hospitalizations for cardiovascular reasons were also reduced. There was an insignificant reduction in hospitalizations for any cause in the enalapril treatment group (for enalapril vs. placebo, respectively, 1166 vs. 1201 first hospitalizations, 2649 vs. 2840 total hospitalizations), although the study was not powered to look for such an effect.

The SOLVD-Prevention trial was not designed to determine whether treatment of asymptomatic patients with low ejection fraction would be superior, with respect to preventing hospitalization, to closer follow-up and use of enalapril at the earliest sign of heart failure. However, under the conditions of follow-up in the SOLVD-Prevention trial (every 4 months at the study clinic; personal physician as needed), 68% of patients on placebo who were hospitalized for heart failure had no prior symptoms recorded which would have signaled initiation of treatment.

The SOLVD-Prevention trial was also not designed to show whether enalapril modified the progression of underlying heart disease.

In another multicenter, placebo-controlled trial (CONSENSUS) limited to patients with NYHA Class IV congestive heart failure and radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly, use of enalapril was associated with improved survival. The results are shown in the following table.

In both CONSENSUS and SOLVD-Treatment trials, patients were also usually receiving digitalis, diuretics or both.

SURVIVAL (%)

Six Months One Year Enalapril Maleate (n=127)

74

64

Placebo (n=126)

56

48

Clinical Pharmacology in Pediatric Patients

A multiple dose pharmacokinetic study was conducted in 40 hypertensive male and female pediatric patients aged 2 months to ≤16 years following daily oral administration of 0.07 to 0.14 mg/kg enalapril maleate. At steady state, the mean effective half-life for accumulation of enalaprilat was 14 hours and the mean urinary recovery of total enalapril and enalaprilat in 24 hours was 68% of the administered dose. Conversion of enalapril to enalaprilat was in the range of 63-76%. The overall results of this study indicate that the pharmacokinetics of enalapril in hypertensive children aged 2 months to ≤16 years are consistent across the studied age groups and consistent with pharmacokinetic historic data in healthy adults.

In a clinical study involving 110 hypertensive pediatric patients 6 to 16 years of age, patients who weighed <50 kg received either 0.625, 2.5 or 20 mg of enalapril daily and patients who weighed ≥50 kg received either 1.25, 5, or 40 mg of enalapril daily. Enalapril administration once daily lowered trough blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner. The dose-dependent antihypertensive efficacy of enalapril was consistent across all subgroups (age, Tanner stage, gender, race). However, the lowest doses studied, 0.625 mg and 1.25 mg, corresponding to an average of 0.02 mg/kg once daily, did not appear to offer consistent antihypertensive efficacy. In this study, Enalapril maleate was generally well tolerated.

In the above pediatric studies, enalapril maleate was given as tablets and for those children and infants who were unable to swallow tablets or who required a lower dose than is available in tablet form, enalapril was administered in a suspension formulation (see Preparation of Suspension under DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). -

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Hypertension

Enalapril maleate is indicated for the treatment of hypertension.

Enalapril maleate is effective alone or in combination with other antihypertensive agents, especially thiazide-type diuretics. The blood pressure lowering effects of enalapril maleate and thiazides are approximately additive.Heart Failure

Enalapril maleate is indicated for the treatment of symptomatic congestive heart failure, usually in combination with diuretics and digitalis. In these patients enalapril maleate improves symptoms, increases survival, and decreases the frequency of hospitalization (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Heart Failure, Mortality Trials for details and limitations of survival trials).Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction

In clinically stable asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction ≤35 percent), enalapril maleate decreases the rate of development of overt heart failure and decreases the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure. (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Heart Failure, Mortality Trials for details and limitations of survival trials.)

In using enalapril maleate, consideration should be given to the fact that another angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, captopril, has caused agranulocytosis, particularly in patients with renal impairment or collagen vascular disease, and that available data are insufficient to show that enalapril maleate does not have a similar risk. (See WARNINGS.)

In considering use of enalapril maleate, it should be noted that in controlled clinical trials ACE inhibitors have an effect on blood pressure that is less in black patients than in non-blacks. In addition, it should be noted that black patients receiving ACE inhibitors have been reported to have a higher incidence of angioedema compared to non-blacks. (See WARNINGS, Head and Neck Angioedema.) - CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Anaphylactoid and Possibly Related Reactions

Presumably because angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors affect the metabolism of eicosanoids and polypeptides, including endogenous bradykinin, patients receiving ACE inhibitors (including enalapril maleate) may be subject to a variety of adverse reactions, some of them serious.

Head and Neck Angioedema: Angioedema of the face, extremities, lips, tongue, glottis and/or larynx has been reported in patients treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, including enalapril maleate. This may occur at any time during treatment. In such cases enalapril maleate should be promptly discontinued and appropriate therapy and monitoring should be provided until complete and sustained resolution of signs and symptoms has occurred. In instances where swelling has been confined to the face and lips the condition has generally resolved without treatment, although antihistamines have been useful in relieving symptoms. Angioedema associated with laryngeal edema may be fatal. Where there is involvement of the tongue, glottis or larynx, likely to cause airway obstruction, appropriate therapy, e.g., Subcutaneous epinephrine solution 1:1000 (0.3 mL to 0.5 mL) and/or measures necessary to ensure a patent airway, should be promptly provided. (See ADVERSE REACTIONS.)

Intestinal Angioedema: Intestinal angioedema has been reported in patients treated with ACE inhibitors. These patients presented with abdominal pain (with or without nausea or vomiting); in some cases there was no prior history of facial angioedema and C-1 esterase levels were normal. The angioedema was diagnosed by procedures including abdominal CT scan or ultrasound, or at surgery, and symptoms resolved after stopping the ACE inhibitor. Intestinal angioedema should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients on ACE inhibitors presenting with abdominal pain.

Patients with a history of angioedema unrelated to ACE inhibitor therapy may be at increased risk of angioedema while receiving an ACE inhibitor (see also INDICATIONS AND USAGE and CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Anaphylactoid reactions during desensitization: Two patients undergoing desensitizing treatment with hymenoptera venom while receiving ACE inhibitors sustained life-threatening anaphylactoid reactions. In the same patients, these reactions were avoided when ACE inhibitors were temporarily withheld, but they reappeared upon inadvertent rechallenge.

Anaphylactoid reactions during membrane exposure: Anaphylactoid reactions have been reported in patients dialyzed with high-flux membranes and treated concomitantly with an ACE inhibitor. Anaphylactoid reactions have also been reported in patients undergoing low-density lipoprotein apheresis with dextran sulfate absorption.Hypotension

Excessive hypotension is rare in uncomplicated hypertensive patients treated with enalapril maleate alone. Patients with heart failure given enalapril maleate commonly have some reduction in blood pressure, especially with the first dose, but discontinuation of therapy for continuing symptomatic hypotension usually is not necessary when dosing instructions are followed; caution should be observed when initiating therapy. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.) Patients at risk for excessive hypotension, sometimes associated with oliguria and/or progressive azotemia, and rarely with acute renal failure and/or death, include those with the following conditions or characteristics: heart failure, hyponatremia, high dose diuretic therapy, recent intensive diuresis or increase in diuretic dose, renal dialysis, or severe volume and/or salt depletion of any etiology. It may be advisable to eliminate the diuretic (except in patients with heart failure), reduce the diuretic dose or increase salt intake cautiously before initiating therapy with enalapril maleate in patients at risk for excessive hypotension who are able to tolerate such adjustments. (See PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions and ADVERSE REACTIONS.) In patients at risk for excessive hypotension, therapy should be started under very close medical supervision and such patients should be followed closely for the first two weeks of treatment and whenever the dose of enalapril and/or diuretic is increased. Similar considerations may apply to patients with ischemic heart or cerebrovascular disease, in whom an excessive fall in blood pressure could result in a myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident.

If excessive hypotension occurs, the patient should be placed in the supine position and, if necessary, receive an intravenous infusion of normal saline. A transient hypotensive response is not a contraindication to further doses of enalapril maleate, which usually can be given without difficulty once the blood pressure has stabilized. If symptomatic hypotension develops, a dose reduction or discontinuation of enalapril maleate or concomitant diuretic may be necessary.

Neutropenia/Agranulocytosis

Another angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, captopril, has been shown to cause agranulocytosis and bone marrow depression, rarely in uncomplicated patients but more frequently in patients with renal impairment especially if they also have a collagen vascular disease. Available data from clinical trials of enalapril are insufficient to show that enalapril does not cause agranulocytosis at similar rates. Marketing experience has revealed cases of neutropenia or agranulocytosis in which a causal relationship to enalapril cannot be excluded. Periodic monitoring of white blood cell counts in patients with collagen vascular disease and renal disease should be considered.Hepatic Failure

Rarely, ACE inhibitors have been associated with a syndrome that starts with cholestatic jaundice and progresses to fulminant hepatic necrosis, and (sometimes) death. The mechanism of this syndrome is not understood. Patients receiving ACE inhibitors who develop jaundice or marked elevations of hepatic enzymes should discontinue the ACE inhibitor and receive appropriate medical follow-up.Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality

ACE inhibitors can cause fetal and neonatal morbidity and death when administered to pregnant women. Several dozen cases have been reported in the world literature. When pregnancy is detected, ACE inhibitors should be discontinued as soon as possible.

In a published retrospective epidemiological study, infants whose mothers had taken an ACE inhibitor during their first trimester of pregnancy appeared to have an increased risk of major congenital malformations compared with infants whose mothers had not undergone first timester exposure to ACE inhibitor drugs. The number of cases of birth defects is small and the findings of this study are not yet been repeated.

The use of ACE inhibitors during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy has been associated with fetal and neonatal injury, including hypotension, neonatal skull hypoplasia, anuria, reversible or irreversible renal failure, and death. Oligohydramnios has also been reported, presumably resulting from decreased fetal renal function; oligohydramnios in this setting has been associated with fetal limb contractures, craniofacial deformation, and hypoplastic lung development. Prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, and patent ductus arteriosus have also been reported, although it is not clear whether these occurrences were due to the ACE-inhibitor exposure.

These adverse effects do not appear to have resulted from intrauterine ACE-inhibitor exposure that has been limited to the first trimester. Mothers whose embryos and fetuses are exposed to ACE inhibitors only during the first trimester should be so informed. Nonetheless, when patients become pregnant, physicians should make every effort to discontinue the use of enalapril maleate as soon as possible.

Rarely (probably less often than once in every thousand pregnancies), no alternative to ACE inhibitors will be found. In these rare cases, the mothers should be apprised of the potential hazards to their fetuses, and serial ultrasound examinations should be performed to assess the intraamniotic environment.

If oligohydramnios is observed, enalapril maleate should be discontinued unless it is considered lifesaving for the mother. Contraction stress testing (CST), a non-stress test (NST), or biophysical profiling (BPP) may be appropriate, depending upon the week of pregnancy. Patients and physicians should be aware, however, that oligohydramnios may not appear until after the fetus has sustained irreversible injury.

Infants with histories of in utero exposure to ACE inhibitors should be closely observed for hypotension, oliguria, and hyperkalemia. If oliguria occurs, attention should be directed towards support of blood pressure and renal perfusion. Exchange transfusion or dialysis may be required as means of reversing hypotension and/or substituting for disordered renal function. Enalapril, which crosses the placenta, has been removed from

neonatal circulation by peritoneal dialysis with some clinical benefit, and theoretically may be removed by exchange transfusion, although there is no experience with the latter procedure.

No teratogenic effects of enalapril were seen in studies of pregnant rats, and rabbits. On a body surface area basis, the doses used were 57 times and 12 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human daily dose (MRHDD). -

PRECAUTIONS

General

Aortic Stenosis/Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: As with all vasodilators, enalapril should be given with caution to patients with obstruction in the outflow tract of the left ventricle.

Impaired Renal Function: As a consequence of inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, changes in renal function may be anticipated in susceptible individuals. In patients with severe heart failure whose renal function may depend on the activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, including enalapril maleate, may be associated with oliguria and/or progressive azotemia and rarely with acute renal failure and/or death.

In clinical studies in hypertensive patients with unilateral or bilateral renal artery stenosis, increases in blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine were observed in 20 percent of patients. These increases were almost always reversible upon discontinuation of enalapril and/or diuretic therapy. In such patients renal function should be monitored during the first few weeks of therapy.

Some patients with hypertension or heart failure with no apparent pre-existing renal vascular disease have developed increases in blood urea and serum creatinine, usually minor and transient, especially when enalapril maleate has been given concomitantly with a diuretic. This is more likely to occur in patients with pre-existing renal impairment. Dosage reduction and/or discontinuation of the diuretic and/or enalapril maleate

may be required.

Evaluation of patients with hypertension or heart failure should always include assessment of renal function. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)

Hyperkalemia: Elevated serum potassium (greater than 5.7 mEq/L) was observed in approximately one percent of hypertensive patients in clinical trials. In most cases these were isolated values which resolved despite continued therapy. Hyperkalemia was a cause of discontinuation of therapy in 0.28 percent of hypertensive patients. In clinical trials in heart failure, hyperkalemia was observed in 3.8 percent of patients but was not a cause for discontinuation.

Risk factors for the development of hyperkalemia include renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, and the concomitant use of potassium-sparing diuretics, potassium supplements and/or potassium-containing salt substitutes, which should be used cautiously, if at all, with enalapril maleate. (See Drug Interactions.)

Cough: Presumably due to the inhibition of the degradation of endogenous bradykinin, persistent nonproductive cough has been reported with all ACE inhibitors, always resolving after discontinuation of therapy. ACE inhibitor-induced cough should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cough.

Surgery/Anesthesia: In patients undergoing major surgery or during anesthesia with agents that produce hypotension, enalapril may block angiotensin II formation secondary to compensatory renin release. If hypotension occurs and is considered to be due to this mechanism, it can be corrected by volume expansion.Information for Patients

Angioedema: Angioedema, including laryngeal edema, may occur at any time during treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, including enalapril. Patients should be so advised and told to report immediately any signs or symptoms suggesting angioedema (swelling of face, extremities, eyes, lips, tongue, difficulty in swallowing or breathing) and to take no more drug until they have consulted with the prescribing physician.

Hypotension: Patients should be cautioned to report light-headedness, especially during the first few days of therapy. If actual syncope occurs, the patients should be told to discontinue the drug until they have consulted with the prescribing physician.

All patients should be cautioned that excessive perspiration and dehydration may lead to an excessive fall in blood pressure because of reduction in fluid volume. Other causes of volume depletion such as vomiting or diarrhea may also lead to a fall in blood pressure; patients should be advised to consult with the physician.

Hyperkalemia: Patients should be told not to use salt substitutes containing potassium without consulting their physician.

Neutropenia: Patients should be told to report promptly any indication of infection (e.g., sore throat, fever) which may be a sign of neutropenia.

Pregnancy: Female patients of childbearing age should be told about the consequences of exposure to ACE inhibitors. These patients should be asked to report pregnancies to their physicians as soon as possible.

NOTE: As with many other drugs, certain advice to patients being treated with enalapril is warranted. This information is intended to aid in the safe and effective use of this medication. It is not a disclosure of all possible adverse or intended effects.Drug Interactions

Hypotension — Patients on Diuretic Therapy: Patients on diuretics and especially those in whom diuretic therapy was recently instituted, may occasionally experience an excessive reduction of blood pressure after initiation of therapy with enalapril. The possibility of hypotensive effects with enalapril can be minimized by either discontinuing the diuretic or increasing the salt intake prior to initiation of treatment with enalapril. If it is necessary to continue the diuretic, provide close medical supervision after the initial dose for at least two hours and until blood pressure has stabilized for at least an additional hour. (See WARNINGS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)

Agents Causing Renin Release: The antihypertensive effect of enalapril maleate is augmented by antihypertensive agents that cause renin release (e.g., diuretics).

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents: In some patients with compromised renal function who are being treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, the co-administration of enalapril may result in a further deterioration of renal function. These effects are usually reversible.

In a clinical pharmacology study, indomethacin or sulindac was administered to hypertensive patients receiving enalapril maleate. In this study there was no evidence of a blunting of the antihypertensive action of enalapril maleate. However, reports suggest that NSAIDs may diminish the antihypertensive effect of ACE inhibitors. This interaction should be given consideration in patients taking NSAIDs concomitantly with ACE inhibitors.

Other Cardiovascular Agents: Enalapril maleate has been used concomitantly with beta adrenergic-blocking agents, methyldopa, nitrates, calcium-blocking agents, hydralazine, prazosin and digoxin without evidence of clinically significant adverse interactions.

Agents Increasing Serum Potassium: Enalapril maleate attenuates potassium loss caused by thiazide-type diuretics. Potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., spironolactone, triamterene, or amiloride), potassium supplements, or potassium-containing salt substitutes may lead to significant increases in serum potassium. Therefore, if concomitant use of these agents is indicated because of demonstrated hypokalemia, they should be used with caution and with frequent monitoring of serum potassium. Potassium sparing agents should generally not be used in patients with heart failure receiving enalapril maleate.

Lithium: Lithium toxicity has been reported in patients receiving lithium concomitantly with drugs which cause elimination of sodium, including ACE inhibitors. A few cases of lithium toxicity have been reported in patients receiving concomitant enalapril maleate and lithium and were reversible upon discontinuation of both drugs. It is recommended that serum lithium levels be monitored frequently if enalapril is administered concomitantly with lithium.

Gold: Nitritoid reactions (symptoms include facial flushing, nausea, vomiting and hypotension) have been reported rarely in patients on therapy with injectable gold (sodium aurothiomalate) and concomitant ACE inhibitor therapy including Enalapril.Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

There was no evidence of a tumorigenic effect when enalapril was administered for 106 weeks to male and female rats at doses up to 90 mg/kg/day or for 94 weeks to male and female mice at doses up to 90 and 180 mg/kg/day, respectively. These doses are 26 times (in rats and female mice) and 13 times (in male mice) the maximum recommended human daily dose (MRHDD) when compared on a body surface area basis.

Neither enalapril maleate nor the active diacid was mutagenic in the Ames microbial mutagen test with or without metabolic activation. Enalapril was also negative in the following genotoxicity studies: rec-assay, reverse mutation assay with E.coli, sister chromatid exchange with cultured mammalian cells and the micronucleus test with mice, as well as in an in vivo cytogenic study using mouse bone marrow.

There were no adverse effects on reproductive performance of male and female rats treated with up to 90 mg/kg/day of enalapril (26 times the MRHDD when compared on a body surface area basis).Pregnancy

Pregnancy Categories C (first trimester) and D (second and third trimesters). See WARNINGS, Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality.Nursing Mothers

Enalapril and enalaprilat have been detected in human breast milk. Because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants from enalapril, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue enalapril maleate, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.Pediatric Use

Antihypertensive effects of enalapril maleate have been established in hypertensive pediatric patients age 1 month to 16 years. Use of enalapril maleate in these age groups is supported by evidence from adequate and well-controlled studies of enalapril maleate in pediatric and adult patients as well as by published literature in pediatric patients. (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Clinical Pharmacology in Pediatric Patients and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION.)

Enalapril maleate is not recommended in neonates and in pediatric patients with glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, as no data are available. -

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Enalapril maleate has been evaluated for safety in more than 10,000 patients, including over 1000 patients treated for one year or more. Enalapril maleate has been found to be generally well tolerated in conrolled clinical trials involving 2987 patients.

For the most part, adverse experiences were mild and transient in nature. In clinical trials, discontinuation of therapy due to clinical adverse experiences was required in 3.3 percent of patients with hypertension and in 5.7 percent of patients with heart failure. The frequency of adverse experiences was not related to total daily dosage within the usual dosage ranges. In patients with hypertension the overall percentage of patients treated with enalapril maleate reporting adverse experiences was comparable to placebo.HYPERTENSION

Adverse experiences occurring in greater than one percent of patients with hypertension treated with enalapril maleate in controlled clinical trials are shown below. In patients treated with enalapril maleate, the maximum duration of therapy was three years; in placebo treated patients the maximum duration of therapy was 12 weeks.

Enalapril Maleate

(n=2314)

Incidence

(discontinuation)

Placebo

(n=230)

Incidence

Body As A Whole

Fatigue

3.0 (<0.1)

2.6

Orthostatic Effets

1.2 (<0.1) 0.0

Asthenia

1.1 (0.1) 0.9

Digestive

Diarrhea

1.4 (<0.1) 1.7

Nausea

1.4 (0.2) 1.7

Nervous/Psychiatric

Headache

5.2 (0.3) 9.1

Dizziness

4.3 (0.4) 4.3

Respiratory

Cough

1.3 (0.1) 0.9

Skin

Rash

1.4 (0.4) 0.4

HEART FAILURE

Adverse experiences occurring in greater than one percent of patients with heart failure treated with enalapril maleate are shown below. The incidences represent the experiences from both controlled and uncontrolled clinical trials (maximum duration of therapy was approximately one year). In the placebo treated patients, the incidences reported are from the controlled trials (maximum duration of therapy is 12 weeks). The percentage of patients with severe heart failure (NYHA Class IV) was 29 percent and 43 percent for patients treated with enalapril maleate and placebo, respectively.

Other serious clinical adverse experiences occurring since the drug was marketed or adverse experiences occurring in 0.5 to 1.0 percent of patients with hypertension or heart failure in clinical trials are listed below and, within each category, are in order of decreasing severity.

Enalapril Maleate

(n=673)

Incidence

(discontinuation)

Placebo

(n=339)

IncidenceBody As A Whole

Orthostatic Effects 2.2 (0.1) 0.3 Syncope 2.2 (0.1) 0.9

Chest Pain 2.1 (0.0)

2.1

Fatigue 1.8 (0.0) 1.8

Abdominal Pain 1.6 (0.4) 2.1

Asthenia 1.6 (0.1)

0.3

Cardiovascular

Hypotension 6.7 (1.9)

0.6

Orthostatic Hypotension 1.6 (0.1)

0.3

Angina Pectoris 1.5 (0.1)

1.8

Myocardial Infarction 1.2 (0.3)

1.8

Digestive

Diarrhea 2.1 (0.1) 1.2

Nausea 1.3 (0.1)

0.6

Vomiting 1.3 (0.0)

0.9

Nervous/Psychiatric

Dizziness 7.9(0.6) 0.6

Headache 1.8 (0.1) 0.9

Vertigo 1.6 (0.1)

1.2

Respiratory

Cough 2.2 (0.0) 0.6

Bronchitis 1.3 (0.0) 0.9

Dyspnea 1.3 (0.1) 0.4

Pneumonia 1.0 (0.0) 2.4

Skin

Rash 1.3 (0.0)

2.4

Urogenital

Urinary Tract Infection 1.3 (0.0) 2.4

Body As A Whole: Anaphylactoid reactions (see WARNINGS, Anaphylactoid and Possibly Related Reactions).

Cardiovascular: Cardiac arrest; myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident, possibly secondary to excessive hypotension in high risk patients (see WARNINGS, Hypotension); pulmonary embolism and infarction; pulmonary edema; rhythm disturbances including atrial tachycardia and bradycardia; atrial fibrillation; palpitation, Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Digestive: Ileus, pancreatitis, hepatic failure, hepatitis (hepatocellular [proven on rechallenge] or cholestatic jaundice) (see WARNINGS, Hepatic Failure), melena, anorexia, dyspepsia, constipation, glossitis, stomatitis, dry mouth.

Hematologic: Rare cases of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and bone marrow depression.

Musculoskeletal: Muscle cramps.

Nervous/Psychiatric: Depression, confusion, ataxia, somnolence, insomnia, nervousness, peripheral neuropathy (e.g., paresthesia, dysesthesia), dream abnormality.

Respiratory: Bronchospasm, rhinorrhea, sore throat and hoarseness, asthma, upper respiratory infection, pulmonary infiltrates, eosinophilic pneumonitis.

Skin: Exfoliative dermatitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pemphigus, herpes zoster, erythema multiforme, urticaria, pruritus, alopecia, flushing, diaphoresis, photosensitivity.

Special Senses: Blurred vision, taste alteration, anosmia, tinnitus, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing.

Urogenital: Renal failure, oliguria, renal dysfunction (see PRECAUTIONS and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION), flank pain, gynecomastia, impotence.

Miscellaneous: A symptom complex has been reported which may include some or all of the following: a positive ANA, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, arthralgia/arthritis, myalgia/ myositis, fever, serositis, vasculitis, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, photosensitivity, rash and other dermatologic manifestations.

Angioedema: Angioedema has been reported in patients receiving enalapril maleate with an incidence higher in black than in non-black patients. Angioedema associated with laryngeal edema may be fatal. If angioedema of the face, extremities, lips, tongue, glottis and/or larynx occurs, treatment with enalapril maleate should be discontinued and appropriate therapy instituted immediately. (See WARNINGS.)

Hypotension: In the hypertensive patients, hypotension occurred in 0.9 percent and syncope occurred in 0.5 percent of patients following the initial dose or during extended therapy. Hypotension or syncope was a cause for discontinuation of Therapy in 0.1 percent of hypertensive patients. In heart failure patients, hypotension occurred in 6.7 percent and syncope occured in 2.2 percent of patients. Hypotension or syncope was a cause for discontinuation of therapy in 1.9 percent of patients with heart failure. (See WARNINGS.)

Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality: See WARNINGS, Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality.

Cough: See PRECAUTIONS, Cough.

Pediatric Patients

The adverse experience profile for pediatric patients appears to be similar to that seen in adult patients.Clinical Laboratory Test Findings

Serum Electrolytes: Hyperkalemia (see PRECAUTIONS), hyponatremia.

Creatinine, Blood Urea Nitrogen: In controlled clinical trials minor increases in blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine, reversible upon discontinuation of therapy, were observed in about 0.2 percent of patients with essential hypertension treated with enalapril maleate alone. Increases are more likely to occur in patients receiving concomitant diuretics or in patients with renal artery stenosis. (See PRECAUTIONS.) In patients with heart failure who were also receiving diuretics with or without digitalis, increases in blood urea nitrogen or serum creatinine, usually reversible upon discontinuation of enalapril maleate and/or other concomitant diuretic therapy, were observed in about 11 percent of patients. Increases in blood urea nitrogen or creatinine were a cause for discontinuation in 1.2 percent of patients.

Hematology: Small decreases in hemoglobin and hematocrit (mean decreases of approximately 0.3 g percent and 1.0 vol percent, respectively) occur frequently in either hypertension or congestive heart failure patients treated with enalapril maleate but are rarely of clinical importance unless another cause of anemia coexists. In clinical trials, less than 0.1 percent of patients discontinued therapy due to anemia. Hemolytic anemia, including cases of hemolysis in patients with G-6-PD deficiency, has been reported; a causal relationship to enalapril cannot be excluded.

Liver Function Tests: Elevations of liver enzymes and/or serum bilirubin have occurred (see WARNINGS, Hepatic Failure). -

OVERDOSAGE

Limited data are available in regard to overdosage in humans. Single oral doses of enalapril above 1,000 mg/kg and ≥1,775 mg/kg were associated with lethality in mice and rats, respectively.

The most likely manifestation of overdosage would be hypotension, for which the usual treatment would be intravenous infusion of normal saline solution.

Enalaprilat may be removed from general circulation by hemodialysis and has been removed from neonatal circulation by peritoneal dialysis. (See WARNINGS, Anaphylactoid reactions during membrane exposure.)

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Hypertension

In patients who are currently being treated with a diuretic, symptomatic hypotension occasionally may occur following the initial dose of Enalapril Maleate Tablets. The diuretic should, if possible, be discontinued for two to three days before beginning therapy with Enalapril Maleate Tablets to reduce the likelihood of hypotension. (See WARNINGS.) If the patient's blood pressure is not controlled with Enalapril Maleate Tablets alone, diuretic therapy may be resumed.

If the diuretic cannot be discontinued an initial dose of 2.5 mg should be used under medical supervision for at least two hours and until blood pressure has stabilized for at least an additional hour. (See WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.)

The recommended initial dose in patients not on diuretics is 5 mg once a day. Dosage should be adjusted according to blood pressure response. The usual dosage range is 10 to 40 mg per day administered in a single dose or two divided doses. In some patients treated once daily, the antihypertensive effect may diminish toward the end of the dosing interval. In such patients, an increase in dosage or twice daily administration should be considered. If blood pressure is not controlled with Enalapril Maleate Tablets alone, a diuretic may be added.

Concomitant administration of Enalapril Maleate Tablets with potassium supplements, potassium salt substitutes, or potassium-sparing diuretics may lead to increases of serum potassium (see PRECAUTIONS).

Dosage Adjustment in Hypertensive Patients with Renal Impairment

The usual dose of enalapril is recommended for patients with a creatinine clearance >30 mL/min (serum creatinine of up to approximately 3 mg/dL). For patients with creatinine clearance ≤30 mL/min (serum creatinine ≥3 mg/dL), the first dose is 2.5 mg once daily. The dosage may be titrated upward until blood pressure is controlled or to a maximum of 40 mg daily.***See WARNINGS, Anaphylactoid reactions during membrane exposure.Renal Status

Creatinine-

Clearance

ml/min

Initial Dose

mg/dayNormal Renal Function

>80 mL/min

5 mg

Mild Impairment

≤80> 30 mL/min 5 mg

Moderate to Severe Impairment

≤30 mL/min 2.5 mg

Dialysis Patients***

- -

2.5 mg on dialysis days†

†Dosage on nondialysis days should be adjusted depending on the blood pressure response.

Heart Failure

Enalapril Maleate Tablets are indicated for the treatment of symptomatic heart failure, usually in combination with diuretics and digitalis. In the placebo-controlled studies that demonstrated improved survival, patients were titrated as tolerated up to 40 mg, administered in two divided doses.

The recommended initial dose is 2.5 mg. The recommended dosing range is 2.5 to 20 mg given twice a day. Doses should be titrated upward, as tolerated, over a period of a few days or weeks. The maximum daily dose administered in clinical trials was 40 mg in divided doses.

After the initial dose of Enalapril Maleate Tablets, the patient should be observed under medical supervision for at least two hours and until blood pressure has stabilized for at least an additional hour. (See WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.) If possible, the dose of any concomitant diuretic should be reduced which may diminish the likelihood of hypotension. The appearance of hypotension after the initial dose of Enalapril Maleate Tablets does not preclude subsequent careful dose titration with the drug, following effective management of the hypotension.

Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction

In the trial that demonstrated efficacy, patients were started on 2.5 mg twice daily and were titrated as tolerated to the targeted daily dose of 20 mg (in divided doses).

After the initial dose of Enalapril Maleate Tablets, the patient should be observed under medical supervision for at least two hours and until blood pressure has stabilized for at least an additional hour. (See WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.) If possible, the dose of any concomitant diuretic should be reduced which may diminish the likelihood of hypotension. The appearance of hypotension after the initial dose of Enalapril Maleate Tablets does not preclude subsequent careful dose titration with the drug, following effective management of the hypotension.

Dosage Adjustment in Patients with Heart Failure and Renal Impairment or Hyponatremia

In patients with heart failure who have hyponatremia (serum sodium less than 130 mEq/L) or with serum creatinine greater than 1.6 mg/dL, therapy should be initiated at 2.5 mg daily under close medical supervision. (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, Heart Failure, WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.) The dose may be increased to 2.5 mg b.i.d., then 5 mg b.i.d. and higher as needed, usually at intervals of four days or more if at the time of dosage adjustment there is not excessive hypotension or significant deterioration of renal function. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg.

Pediatric Hypertensive Patients

The usual recommended starting dose is 0.08 mg/kg (up to 5 mg) once daily. Dosage should be adjusted according to blood pressure response. Doses above 0.58 mg/kg (or in excess of 40 mg) have not been studied in pediatric patients.

(See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Clinical Pharmacology in Pediatric Patients.)

Enalapril maleate is not recommended in neonates and in pediatric patients with glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/ min/1.73 m2, as no data are available.

Preparation of Suspension (for 200 mL of a 1.0 mg/mL suspension)

Add 50 mL of Bicitra®** to a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle containing ten 20 mg tablets of Enalapril maleate and shake for at least 2 minutes. Let concentrate stand for 60 minutes. Following the 60-minute hold time, shake the concentrate for an additional minute. Add 150 mL of Ora-Sweet SFTM*** to the concentrate in the PET bottle and shake the suspension to disperse the ingredients.

The suspension should be refrigerated at 2-8°C (36-46°F) and can be stored for up to 30 days. Shake the suspension before each use. -

HOW SUPLLIED

Enalapril Maleate is supplied by State of Florida DOH Central Pharmacy as follows:

StorageNDC Strength Quantity/Form Color Source Prod. Code 53808-0966-1 2.5 mg 30 Tablets in a Blister Pack White 64679-923 53808-0242-1 5 mg 30 Tablets in a Blister Pack White 64679-924 53808-0243-1 10 mg 30 Tablets in a Blister Pack Light Salmon 64679-925 53808-0244-1 20 mg 30 Tablets in a Blister Pack Light Beige 64679-926

Store below 30°C (86°F) and avoid transient temperatures above 50°C (122°F). Keep container tightly closed. Protect from moisture.

Dispense in a tight container as per USP, if product package is subdivided.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

** Registered trademark of Alza Corporation.

*** Trademark of Paddock Laboratories, Inc.

Manufactured by:

Wockhardt Limited,

Mumbai, India.

Distributed by:

Wockhardt USA LLC.

20 Waterview Blvd.

Parsippany, NJ 07054

USA.This Product was Repackaged By:

State of Florida DOH Central Pharmacy

104-2 Hamilton Park Drive

Tallahassee, FL 32304

United States

- Label Image for 2.5mg

- Label Image for 5mg

- Label Image for 10mg

- Label Image for 20mg

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ENALAPRIL MALEATE

enalapril maleate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 53808-0966(NDC:64679-923) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ENALAPRIL MALEATE (UNII: 9O25354EPJ) (ENALAPRIL - UNII:69PN84IO1A) ENALAPRIL 2.5 mg Product Characteristics Color white (White) Score score with uneven pieces Shape ROUND (round flat-faced beveled edged) Size 6mm Flavor Imprint Code W;923 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 53808-0966-1 30 in 1 BLISTER PACK Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075483 07/01/2009 ENALAPRIL MALEATE

enalapril maleate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 53808-0242(NDC:64679-924) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ENALAPRIL MALEATE (UNII: 9O25354EPJ) (ENALAPRIL - UNII:69PN84IO1A) ENALAPRIL 5 mg Product Characteristics Color white (White) Score score with uneven pieces Shape ROUND (round flat-faced beveled edged) Size 8mm Flavor Imprint Code W;924 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 53808-0242-1 30 in 1 BLISTER PACK Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075483 07/01/2009 ENALAPRIL MALEATE

enalapril maleate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 53808-0243(NDC:64679-925) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ENALAPRIL MALEATE (UNII: 9O25354EPJ) (ENALAPRIL - UNII:69PN84IO1A) ENALAPRIL 10 mg Product Characteristics Color orange (Light Salmon) Score no score Shape ROUND (round flat-faced beveled edged) Size 8mm Flavor Imprint Code W;925 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 53808-0243-1 30 in 1 BLISTER PACK Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075483 07/01/2009 ENALAPRIL MALEATE

enalapril maleate tabletProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 53808-0244(NDC:64679-926) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ENALAPRIL MALEATE (UNII: 9O25354EPJ) (ENALAPRIL - UNII:69PN84IO1A) ENALAPRIL 20 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength STEARIC ACID (UNII: 4ELV7Z65AP) Product Characteristics Color brown (Light Beige) Score no score Shape ROUND (round flat-faced beveled edged) Size 8mm Flavor Imprint Code W;926 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 53808-0244-1 30 in 1 BLISTER PACK Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075483 07/01/2009 Labeler - State of Florida DOH Central Pharmacy (829348114) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Sandhills Packaging 825138717 repack

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.