DIVALPROEX SODIUM DELAYED-RELEASE- divalproex sodium tablet, film coated

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Drug Details [pdf]

- N/A - Section Title Not Found In Database

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

BOX WARNING

HEPATOTOXICITY

HEPATIC FAILURE RESULTING IN FATALITIES HAS OCCURRED IN PATIENTS RECEIVING VALPROIC ACID AND ITS DERIVATIVES. EXPERIENCE HAS INDICATED THAT CHILDREN UNDER THE AGE OF TWO YEARS ARE AT A CONSIDERABLY INCREASED RISK OF DEVELOPING FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY, ESPECIALLY THOSE ON MULTIPLE ANTICONVULSANTS, THOSE WITH CONGENITAL METABOLIC DISORDERS, THOSE WITH SEVERE SEIZURE DISORDERS ACCOMPANIED BY MENTAL RETARDATION, AND THOSE WITH ORGANIC BRAIN DISEASE. WHEN DIVALPROEX SODIUM IS USED IN THIS PATIENT GROUP, IT SHOULD BE USED WITH EXTREME CAUTION AND AS A SOLE AGENT. THE BENEFITS OF THERAPY SHOULD BE WEIGHED AGAINST THE RISKS. ABOVE THIS AGE GROUP, EXPERIENCE IN EPILEPSY HAS INDICATED THAT THE INCIDENCE OF FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY DECREASES CONSIDERABLY IN PROGRESSIVELY OLDER PATIENT GROUPS.

THESE INCIDENTS USUALLY HAVE OCCURRED DURING THE FIRST SIX MONTHS OF TREATMENT. SERIOUS OR FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY MAY BE PRECEDED BY NON-SPECIFIC SYMPTOMS SUCH AS MALAISE, WEAKNESS, LETHARGY, FACIAL EDEMA, ANOREXIA, AND VOMITING. IN PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY, A LOSS OF SEIZURE CONTROL MAY ALSO OCCUR. PATIENTS SHOULD BE MONITORED CLOSELY FOR APPEARANCE OF THESE SYMPTOMS. LIVER FUNCTION TESTS SHOULD BE PERFORMED PRIOR TO THERAPY AND AT FREQUENT INTERVALS THEREAFTER, ESPECIALLY DURING THE FIRST SIX MONTHS.

TERATOGENICITY

VALPROATE CAN PRODUCE TERATOGENIC EFFECTS SUCH AS NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS (E.G., SPINA BIFIDA)ACCORDINGLY, THE USE OF DIVALPROEX SODIUM DELAYED-RELEASE TABLETS IN WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING POTENTIAL REQUIRES THAT THE BENEFITS OF ITS USE BE WEIGHED AGAINST THE RISK OF INJURY TO THE FETUS. THIS IS ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT WHEN THE TREATMENT OF A SPONTANEOUSLY REVERSIBLE CONDITION NOT ORDINARILY ASSOCIATED WITH PERMANENT INJURY OR RISK OF DEATH (E.G., MIGRAINE) IS CONTEMPLATED. SEE WARNINGS, INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS.

AN INFORMATION SHEET DESCRIBING THE TERATOGENIC POTENTIAL OF VALPROATE IS AVAILABLE FOR PATIENTS.

PANCREATITIS

CASES OF LIFE-THREATENING PANCREATITIS HAVE BEEN REPORTED IN BOTH CHILDREN AND ADULTS RECEIVING VALPROATE. SOME OF THE CASES HAVE BEEN DESCRIBED AS HEMORRHAGIC WITH A RAPID PROGRESSION FROM INITIAL SYMPTOMS TO DEATH. CASES HAVE BEEN REPORTED SHORTLY AFTER INITIAL USE AS WELL AS AFTER SEVERAL YEARS OF USE. PATIENTS AND GUARDIANS SHOULD BE WARNED THAT ABDOMINAL PAIN, NAUSEA, VOMITING, AND/OR ANOREXIA CAN BE SYMPTOMS OF PANCREATITIS THAT REQUIRE PROMPT MEDICAL EVALUATION. IF PANCREATITIS IS DIAGNOSED, VALPROATE SHOULD ORDINARILY BE DISCONTINUED. ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT FOR THE UNDERLYING MEDICAL CONDITION SHOULD BE INITIATED AS CLINICALLY INDICATED. (See WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS.)

-

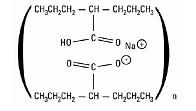

DESCRIPTION

Divalproex sodium is a stable co-ordination compound comprised of sodium valproate and valproic acid in a 1:1 molar relationship and formed during the partial neutralization of valproic acid with 0.5 equivalent of sodium hydroxide. Chemically it is designated as sodium hydrogen bis(2-propylpentanoate). Divalproex sodium has the following structure:

Divalproex sodium occurs as a white powder with a characteristic odor.

Divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets are for oral administration. Divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets are supplied in three dosage strengths containing divalproex sodium equivalent to 125 mg, 250 mg, or 500 mg of valproic acid.

Inactive Ingredients

Divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets: pregelatinized starch, povidone, microcrystalline cellulose, silicon dioxide, opadry clear, methacrylic acid co-polymer, sodium hydroxide, simethicone emulsion, triethyl citrate, talc, vanilla flavor and opacode black.

In addition, individual tablets contain:

250 mg tablets: Ferric oxide.

500 mg tablets: FD&C Blue No. 1.

The components of opadry clear are hypromellose and polyethylene glycol 6000 and the components of opacode black are shellac glaze, iron oxide black, n-butyl alcohol, industrial methylated spirit, lecithin (soya), antifoam DC 1510 (food grade).

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacodynamics

Divalproex sodium dissociates to the valproate ion in the gastrointestinal tract. The mechanisms by which valproate exerts its therapeutic effects have not been established. It has been suggested that its activity in epilepsy is related to increased brain concentrations of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption/Bioavailability

Equivalent oral doses of divalproex sodium products and valproic acid capsules deliver equivalent quantities of valproate ion systemically. Although the rate of valproate ion absorption may vary with the formulation administered (liquid, solid, or sprinkle), conditions of use (e.g., fasting or postprandial) and the method of administration (e.g., whether the contents of the capsule are sprinkled on food or the capsule is taken intact), these differences should be of minor clinical importance under the steady state conditions achieved in chronic use in the treatment of epilepsy.

However, it is possible that differences among the various valproate products in Tmax and Cmax could be important upon initiation of treatment. For example, in single dose studies, the effect of feeding had a greater influence on the rate of absorption of the tablet (increase in Tmax from 4 to 8 hours) than on the absorption of the sprinkle capsules (increase in Tmax from 3.3 to 4.8 hours).

While the absorption rate from the G.I. tract and fluctuation in valproate plasma concentrations vary with dosing regimen and formulation, the efficacy of valproate as an anticonvulsant in chronic use is unlikely to be affected. Experience employing dosing regimens from once-a-day to four-times-a-day, as well as studies in primate epilepsy models involving constant rate infusion, indicate that total daily systemic bioavailability (extent of absorption) is the primary determinant of seizure control and that differences in the ratios of plasma peak to trough concentrations between valproate formulations are inconsequential from a practical clinical standpoint. Whether or not rate of absorption influences the efficacy of valproate as an antimanic or antimigraine agent is unknown.

Co-administration of oral valproate products with food and substitution among the various divalproex sodium and valproic acid formulations should cause no clinical problems in the management of patients with epilepsy (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Nonetheless, any changes in dosage administration, or the addition or discontinuance of concomitant drugs should ordinarily be accompanied by close monitoring of clinical status and valproate plasma concentrations.

Distribution

Protein Binding

The plasma protein binding of valproate is concentration dependent and the free fraction increases from approximately 10% at 40 mcg/mL to 18.5% at 130 mcg/mL. Protein binding of valproate is reduced in the elderly, in patients with chronic hepatic diseases, in patients with renal impairment, and in the presence of other drugs (e.g., aspirin). Conversely, valproate may displace certain protein-bound drugs (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine, warfarin, and tolbutamide). (See PRECAUTIONS - Drug Interactions for more detailed information on the pharmacokinetic interactions of valproate with other drugs.)

Metabolism

Valproate is metabolized almost entirely by the liver. In adult patients on monotherapy, 30 to 50% of an administered dose appears in urine as a glucuronide conjugate. Mitochondrial β-oxidation is the other major metabolic pathway, typically accounting for over 40% of the dose. Usually, less than 15 to 20% of the dose is eliminated by other oxidative mechanisms. Less than 3% of an administered dose is excreted unchanged in urine.

The relationship between dose and total valproate concentration is nonlinear; concentration does not increase proportionally with the dose, but rather, increases to a lesser extent due to saturable plasma protein binding. The kinetics of unbound drug are linear.

Elimination

Mean plasma clearance and volume of distribution for total valproate are 0.56 L/hr/1.73 m2 and 11 L/1.73 m2, respectively. Mean plasma clearance and volume of distribution for free valproate are 4.6 L/hr/1.73 m2 and 92 L/1.73 m2. Mean terminal half-life for valproate monotherapy ranged from 9 to 16 hours following oral dosing regimens of 250 to 1000 mg.

The estimates cited apply primarily to patients who are not taking drugs that affect hepatic metabolizing enzyme systems. For example, patients taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital) will clear valproate more rapidly. Because of these changes in valproate clearance, monitoring of antiepileptic concentrations should be intensified whenever concomitant antiepileptics are introduced or withdrawn.

Special Populations

Effect of Age

Neonates

Children within the first two months of life have a markedly decreased ability to eliminate valproate compared to older children and adults. This is a result of reduced clearance (perhaps due to delay in development of glucuronosyltransferase and other enzyme systems involved in valproate elimination) as well as increased volume of distribution (in part due to decreased plasma protein binding). For example, in one study, the half-life in children under 10 days ranged from 10 to 67 hours compared to a range of 7 to 13 hours in children greater than 2 months.

Children

Pediatric patients (i.e., between 3 months and 10 years) have 50% higher clearances expressed on weight (i.e., mL/min/kg) than do adults. Over the age of 10 years, children have pharmacokinetic parameters that approximate those of adults.

Elderly

The capacity of elderly patients (age range: 68 to 89 years) to eliminate valproate has been shown to be reduced compared to younger adults (age range: 22 to 26). Intrinsic clearance is reduced by 39%; the free fraction is increased by 44%. Accordingly, the initial dosage should be reduced in the elderly (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Effect of Gender

There are no differences in the body surface area adjusted unbound clearance between males and females (4.8 ± 0.17 and 4.7 ± 0.07 L/hr per 1.73 m2, respectively).

Effect of Disease

Liver Disease

(See BOXED WARNING, CONTRAINDICATIONS, and WARNINGS). Liver disease impairs the capacity to eliminate valproate. In one study, the clearance of free valproate was decreased by 50% in 7 patients with cirrhosis and by 16% in 4 patients with acute hepatitis, compared with 6 healthy subjects. In that study, the half-life of valproate was increased from 12 to 18 hours. Liver disease is also associated with decreased albumin concentrations and larger unbound fractions (2 to 2.6 fold increase) of valproate. Accordingly, monitoring of total concentrations may be misleading since free concentrations may be substantially elevated in patients with hepatic disease whereas total concentrations may appear to be normal.

Renal Disease

A slight reduction (27%) in the unbound clearance of valproate has been reported in patients with renal failure (creatinine clearance < 10 mL/minute); however, hemodialysis typically reduces valproate concentrations by about 20%. Therefore, no dosage adjustment appears to be necessary in patients with renal failure. Protein binding in these patients is substantially reduced; thus, monitoring total concentrations may be misleading.

Plasma Levels and Clinical Effect

The relationship between plasma concentration and clinical response is not well documented. One contributing factor is the nonlinear, concentration dependent protein binding of valproate which affects the clearance of the drug. Thus, monitoring of total serum valproate cannot provide a reliable index of the bioactive valproate species.

For example, because the plasma protein binding of valproate is concentration dependent, the free fraction increases from approximately 10% at 40 mcg/mL to 18.5% at 130 mcg/mL. Higher than expected free fractions occur in the elderly, in hyperlipidemic patients, and in patients with hepatic and renal diseases.

Epilepsy

The therapeutic range in epilepsy is commonly considered to be 50 to 100 mcg/mL of total valproate, although some patients may be controlled with lower or higher plasma concentrations.

Mania

In placebo-controlled clinical trials of acute mania, patients were dosed to clinical response with trough plasma concentrations between 50 and 125 mcg/mL (See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Clinical Trials

Mania

The effectiveness of divalproex sodium for the treatment of acute mania was demonstrated in two 3 week, placebo controlled, parallel group studies.

(1) Study 1: The first study enrolled adult patients who met DSM-III-R criteria for Bipolar Disorder and who were hospitalized for acute mania. In addition, they had a history of failing to respond to or not tolerating previous lithium carbonate treatment. Divalproex sodium was initiated at a dose of 250 mg tid and adjusted to achieve serum valproate concentrations in a range of 50 to 100 mcg/mL by day 7. Mean divalproex sodium doses for completers in this study were 1118, 1525, and 2402 mg/day at Days 7, 14, and 21, respectively. Patients were assessed on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; score ranges from 0 to 60), an augmented Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-A), and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS). Baseline scores and change from baseline in the Week 3 endpoint (last-observation-carry-forward) analysis were as follows:

Study 1 YMRS Total Score - * Mean score at baseline

- † Change from baseline to Week 3 (LOCF)

- ‡ Difference in change from baseline to Week 3 endpoint (LOCF) between divalproex sodium and placebo

Group Baseline* BL to Wk 3† Difference‡ Placebo 28.8 + 0.2 Divalproex sodium 28.5 - 9.5 9.7 BPRS-A Total Score Group Baseline* BL to Wk 3† Difference‡ Placebo 76.2 + 1.8 Divalproex sodium 76.4 - 17 18.8 GAS Score Group Baseline* BL to Wk 3† Difference‡ Placebo 31.8 0 Divalproex sodium 30.3 + 18.1 18.1 Divalproex sodium was statistically significantly superior to placebo on all three measures of outcome.

(2) Study 2: The second study enrolled adult patients who met Research Diagnostic Criteria for manic disorder and who were hospitalized for acute mania. Divalproex sodium was initiated at a dose of 250 mg tid and adjusted within a dose range of 750 to 2500 mg/day to achieve serum valproate concentrations in a range of 40 to 150 mcg/mL. Mean divalproex sodium doses for completers in this study were 1116, 1683, and 2006 mg/day at Days 7, 14, and 21, respectively. Study 2 also included a lithium group for which lithium doses for completers were 1312, 1869, and 1984 mg/day at Days 7, 14, and 21, respectively. Patients were assessed on the Manic Rating Scale (MRS; score ranges from 11 to 63), and the primary outcome measures were the total MRS score, and scores for two subscales of the MRS, i.e., the Manic Syndrome Scale (MSS) and the Behavior and Ideation Scale (BIS). Baseline scores and change from baseline in the Week 3 endpoint (last-observation- carry-forward) analysis were as follows:

Study 2 MRS Total Score - * Mean score at baseline

- † Change from baseline to Day 21 (LOCF)

- ‡ Difference in change from baseline to Day 21 endpoint (LOCF) between divalproex sodium and placebo and lithium and placebo

Group Baseline* BL to Day 21† Difference‡ Placebo 38.9 - 4.4 Lithium 37.9 - 10.5 6.1 Divalproex sodium 38.1 - 9.5 5.1 MSS Total Score Group Baseline* BL to Day 21† Difference‡ Placebo 18.9 - 2.5 Lithium 18.5 - 6.2 3.7 Divalproex sodium 18.9 - 6 3.5 BIS Total Score Group Baseline* BL to Day 21† Difference‡ Placebo 16.4 - 1.4 Lithium 16 - 3.8 2.4 Divalproex sodium 15.7 - 3.2 1.8 Divalproex sodium was statistically significantly superior to placebo on all three measures of outcome. An exploratory analysis for age and gender effects on outcome did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of age or gender.

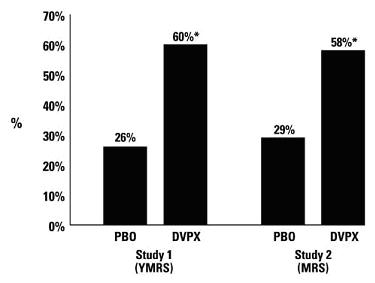

A comparison of the percentage of patients showing ≥ 30% reduction in the symptom score from baseline in each treatment group, separated by study, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Percentage of Patients Achieving ≥ 30% Reduction in Symptom Score From Baseline

* p < 0.05

PBO = placebo, DVPX = Divalproex sodium

Migraine

The results of two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials established the effectiveness of divalproex sodium in the prophylactic treatment of migraine headache.

Both studies employed essentially identical designs and recruited patients with a history of migraine with or without aura (of at least 6 months in duration) who were experiencing at least 2 migraine headaches a month during the 3 months prior to enrollment. Patients with cluster headaches were excluded. Women of childbearing potential were excluded entirely from one study, but were permitted in the other if they were deemed to be practicing an effective method of contraception.

In each study following a 4 week single-blind placebo baseline period, patients were randomized, under double blind conditions, to divalproex sodium or placebo for a 12 week treatment phase, comprised of a 4 week dose titration period followed by an 8 week maintenance period. Treatment outcome was assessed on the basis of 4 week migraine headache rates during the treatment phase.

In the first study, a total of 107 patients (24 M, 83 F), ranging in age from 26 to 73 were randomized 2:1, divalproex sodium to placebo. Ninety patients completed the 8 week maintenance period. Drug dose titration, using 250 mg tablets, was individualized at the investigator's discretion. Adjustments were guided by actual/sham trough total serum valproate levels in order to maintain the study blind. In patients on divalproex sodium doses ranged from 500 to 2500 mg a day. Doses over 500 mg were given in three divided doses (TID). The mean dose during the treatment phase was 1087 mg/day resulting in a mean trough total valproate level of 72.5 mcg/mL, with a range of 31 to 133 mcg/mL.

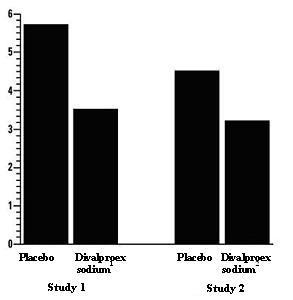

The mean 4 week migraine headache rate during the treatment phase was 5.7 in the placebo group compared to 3.5 in the divalproex sodium group (see Figure 2). These rates were significantly different.

In the second study, a total of 176 patients (19 males and 157 females), ranging in age from 17 to 76 years, were randomized equally to one of three divalproex sodium dose groups (500, 1000, or 1500 mg/day) or placebo. The treatments were given in two divided doses (BID). One hundred thirty-seven patients completed the 8 week maintenance period. Efficacy was to be determined by a comparison of the 4 week migraine headache rate in the combined 1000/1500 mg/day group and placebo group.

The initial dose was 250 mg daily. The regimen was advanced by 250 mg every 4 days (8 days for 500 mg/day group), until the randomized dose was achieved. The mean trough total valproate levels during the treatment phase were 39.6, 62.5, and 72.5 mcg/mL in the divalproex sodium 500, 1000, and 1500 mg/day groups, respectively.

The mean 4 week migraine headache rates during the treatment phase, adjusted for differences in baseline rates, were 4.5 in the placebo group, compared to 3.3, 3, and 3.3 in the divalproex sodium 500, 1000, and 1500 mg/day groups, respectively, based on intent-to-treat results (see Figure 2). Migraine headache rates in the combined divalproex sodium 1000/1500 mg group were significantly lower than in the placebo group.

Figure 2. Mean 4 week Migraine Rates

1 Mean dose of divalproex sodium was 1087 mg/day.

2 Dose of divalproex sodium was 500 or 1000 mg/day.

Epilepsy

The efficacy of divalproex sodium in reducing the incidence of complex partial seizures (CPS) that occur in isolation or in association with other seizure types was established in two controlled trials.

In one, multiclinic, placebo controlled study employing an add-on design, (adjunctive therapy) 144 patients who continued to suffer eight or more CPS per 8 weeks during an 8 week period of monotherapy with doses of either carbamazepine or phenytoin sufficient to assure plasma concentrations within the “therapeutic range” were randomized to receive, in addition to their original antiepilepsy drug (AED), either divalproex sodium or placebo. Randomized patients were to be followed for a total of 16 weeks. The following table presents the findings.

Adjunctive Therapy Study Median Incidence of CPS per 8 Weeks Add-on

TreatmentNumber

of PatientsBaseline

IncidenceExperimental

Incidence- * Reduction from baseline statistically significantly greater for divalproex sodium than placebo at p ≤ 0.05 level.

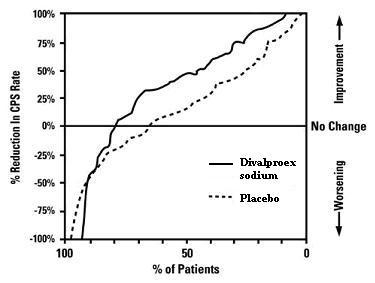

Divalproex sodium 75 16 8.9* Placebo 69 14.5 11.5 Figure 3 presents the proportion of patients (X axis) whose percentage reduction from baseline in complex partial seizure rates was at least as great as that indicated on the Y axis in the adjunctive therapy study. A positive percent reduction indicates an improvement (i.e., a decrease in seizure frequency), while a negative percent reduction indicates worsening. Thus, in a display of this type, the curve for an effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for placebo. This figure shows that the proportion of patients achieving any particular level of improvement was consistently higher for divalproex sodium than for placebo. For example, 45% of patients treated with divalproex sodium had a ≥ 50% reduction in complex partial seizure rate compared to 23% of patients treated with placebo.

Figure 3.

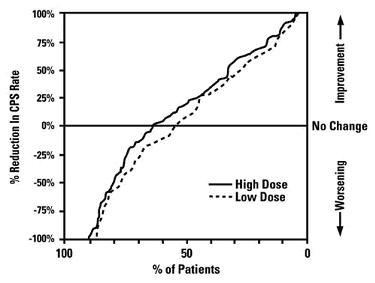

The second study assessed the capacity of divalproex sodium to reduce the incidence of CPS when administered as the sole AED. The study compared the incidence of CPS among patients randomized to either a high or low dose treatment arm. Patients qualified for entry into the randomized comparison phase of this study only if 1) they continued to experience 2 or more CPS per 4 weeks during an 8 to 12 week long period of monotherapy with adequate doses of an AED (i.e., phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, or primidone) and 2) they made a successful transition over a two week interval to divalproex sodium. Patients entering the randomized phase were then brought to their assigned target dose, gradually tapered off their concomitant AED and followed for an interval as long as 22 weeks. Less than 50% of the patients randomized, however, completed the study. In patients converted to divalproex sodium monotherapy, the mean total valproate concentrations during monotherapy were 71 and 123 mcg/mL in the low dose and high dose groups, respectively.

The following table presents the findings for all patients randomized who had at least one post-randomization assessment.

Monotherapy Study Median Incidence of CPS per 8 Weeks Treatment Number of

PatientsBaseline

IncidenceRandomized

Phase Incidence- * Reduction from baseline statistically significantly greater for high dose than low dose at p ≤ 0.05 level.

High dose Divalproex sodium 131 13.2 10.7* Low dose Divalproex sodium 134 14.2 13.8 Figure 4 presents the proportion of patients (X axis) whose percentage reduction from baseline in complex partial seizure rates was at least as great as that indicated on the Y axis in the monotherapy study. A positive percent reduction indicates an improvement (i.e., a decrease in seizure frequency), while a negative percent reduction indicates worsening. Thus, in a display of this type, the curve for a more effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for a less effective treatment. This figure shows that the proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction was consistently higher for high dose divalproex sodium than for low dose divalproex sodium. For example, when switching from carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital or primidone monotherapy to high dose divalproex sodium monotherapy, 63% of patients experienced no change or a reduction in complex partial seizure rates compared to 54% of patients receiving low dose divalproex sodium.

Figure 4

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Mania

Divalproex sodium is indicated for the treatment of the manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder. A manic episode is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood. Typical symptoms of mania include pressure of speech, motor hyperactivity, reduced need for sleep, flight of ideas, grandiosity, poor judgement, aggressiveness, and possible hostility.

The efficacy of divalproex sodium was established in 3 week trials with patients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for bipolar disorder who were hospitalized for acute mania (See Clinical Trials under CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

The safety and effectiveness of divalproex sodium for long-term use in mania, i.e., more than 3 weeks, has not been systematically evaluated in controlled clinical trials. Therefore, physicians who elect to use divalproex sodium for extended periods should continually reevaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.

Epilepsy

Divalproex sodium is indicated as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in the treatment of patients with complex partial seizures that occur either in isolation or in association with other types of seizures. Divalproex sodium is also indicated for use as sole and adjunctive therapy in the treatment of simple and complex absence seizures, and adjunctively in patients with multiple seizure types that include absence seizures.

Simple absence is defined as very brief clouding of the sensorium or loss of consciousness accompanied by certain generalized epileptic discharges without other detectable clinical signs. Complex absence is the term used when other signs are also present.

Migraine

Divalproex sodium is indicated for prophylaxis of migraine headaches. There is no evidence that divalproex sodium is useful in the acute treatment of migraine headaches. Because valproic acid may be a hazard to the fetus, divalproex sodium should be considered for women of childbearing potential only after this risk has been thoroughly discussed with the patient and weighed against the potential benefits of treatment (see WARNINGS - Usage In Pregnancy, PRECAUTIONS- Information for Patients).

SEE WARNINGS FOR STATEMENT REGARDING FATAL HEPATIC DYSFUNCTION.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

DIVALPROEX SODIUM SHOULD NOT BE ADMINISTERED TO PATIENTS WITH HEPATIC DISEASE OR SIGNIFICANT HEPATIC DYSFUNCTION.

Divalproex sodium is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to the drug.

Divalproex sodium is contraindicated in patients with known urea cycle disorders (See WARNINGS).

-

WARNINGS

Hepatotoxicity

Hepatic failure resulting in fatalities has occurred in patients receiving valproic acid. These incidents usually have occurred during the first six months of treatment. Serious or fatal hepatotoxicity may be preceded by non-specific symptoms such as malaise, weakness, lethargy, facial edema, anorexia, and vomiting. In patients with epilepsy, a loss of seizure control may also occur. Patients should be monitored closely for appearance of these symptoms. Liver function tests should be performed prior to therapy and at frequent intervals thereafter, especially during the first six months. However, physicians should not rely totally on serum biochemistry since these tests may not be abnormal in all instances, but should also consider the results of careful interim medical history and physical examination.

Caution should be observed when administering divalproex sodium products to patients with a prior history of hepatic disease. Patients on multiple anticonvulsants, children, those with congenital metabolic disorders, those with severe seizure disorders accompanied by mental retardation, and those with organic brain disease may be at particular risk. Experience has indicated that children under the age of two years are at a considerably increased risk of developing fatal hepatotoxicity, especially those with the aforementioned conditions. When divalproex sodium is used in this patient group, it should be used with extreme caution and as a sole agent. The benefits of therapy should be weighed against the risks. Above this age group, experience in epilepsy has indicated that the incidence of fatal hepatotoxicity decreases considerably in progressively older patient groups.

The drug should be discontinued immediately in the presence of significant hepatic dysfunction, suspected or apparent. In some cases, hepatic dysfunction has progressed in spite of discontinuation of drug.

Pancreatitis

Cases of life-threatening pancreatitis have been reported in both children and adults receiving valproate. Some of the cases have been described as hemorrhagic with rapid progression from initial symptoms to death. Some cases have occurred shortly after initial use as well as after several years of use. The rate based upon the reported cases exceeds that expected in the general population and there have been cases in which pancreatitis recurred after rechallenge with valproate. In clinical trials, there were 2 cases of pancreatitis without alternative etiology in 2416 patients, representing 1044 patient-years experience. Patients and guardians should be warned that abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or anorexia can be symptoms of pancreatitis that require prompt medical evaluation. If pancreatitis is diagnosed, valproate should ordinarily be discontinued. Alternative treatment for the underlying medical condition should be initiated as clinically indicated (see BOXED WARNING).

Urea Cycle Disorders (UCD)

Divalproex sodium is contraindicated in patients with known urea cycle disorders. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy, sometimes fatal, has been reported following initiation of valproate therapy in patients with urea cycle disorders, a group of uncommon genetic abnormalities, particularly ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Prior to the initiation of valproate therapy, evaluation for UCD should be considered in the following patients: 1) those with a history of unexplained encephalopathy or coma, encephalopathy associated with a protein load, pregnancy-related or postpartum encephalopathy, unexplained mental retardation, or history of elevated plasma ammonia or glutamine; 2) those with cyclical vomiting and lethargy, episodic extreme irritability, ataxia, low BUN, or protein avoidance; 3) those with a family history of UCD or a family history of unexplained infant deaths (particularly males); 4) those with other signs or symptoms of UCD. Patients who develop symptoms of unexplained hyperammonemic encephalopathy while receiving valproate therapy should receive prompt treatment (including discontinuation of valproate therapy) and be evaluated for underlying urea cycle disorders (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and PRECAUTIONS).

Somnolence in the Elderly

In a double-blind, multicenter trial of valproate in elderly patients with dementia (mean age = 83 years), doses were increased by 125 mg/day to a target dose of 20 mg/kg/day. A significantly higher proportion of valproate patients had somnolence compared to placebo, and although not statistically significant, there was a higher proportion of patients with dehydration. Discontinuations for somnolence were also significantly higher than with placebo. In some patients with somnolence (approximately one-half), there was associated reduced nutritional intake and weight loss. There was a trend for the patients who experienced these events to have a lower baseline albumin concentration, lower valproate clearance, and a higher BUN. In elderly patients, dosage should be increased more slowly and with regular monitoring for fluid and nutritional intake, dehydration, somnolence, and other adverse events. Dose reductions or discontinuation of valproate should be considered in patients with decreased food or fluid intake and in patients with excessive somnolence (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Thrombocytopenia

The frequency of adverse effects (particularly elevated liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia [see PRECAUTIONS]) may be dose-related. In a clinical trial of divalproex sodium as monotherapy in patients with epilepsy, 34/126 patients (27%) receiving approximately 50 mg/kg/day on average, had at least one value of platelets ≤ 75 x 109/L. Approximately half of these patients had treatment discontinued, with return of platelet counts to normal. In the remaining patients, platelet counts normalized with continued treatment. In this study, the probability of thrombocytopenia appeared to increase significantly at total valproate concentrations of ≥ 110 mcg/mL (females) or ≥ 135 mcg/mL (males). The therapeutic benefit which may accompany the higher doses should therefore be weighed against the possibility of a greater incidence of adverse effects.

Usage In Pregnancy

VALPROATE CAN PRODUCE TERATOGENIC EFFECTS. DATA SUGGEST THAT THERE IS AN INCREASED INCIDENCE OF CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH THE USE OF VALPROATE BY WOMEN WITH SEIZURE DISORDERS DURING PREGNANCY WHEN COMPARED TO THE INCIDENCE IN WOMEN WITH SEIZURE DISORDERS WHO DO NOT USE ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS DURING PREGNANCY, THE INCIDENCE IN WOMEN WITH SEIZURE DISORDERS WHO USE OTHER ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS, AND THE BACKGROUND INCIDENCE FOR THE GENERAL POPULATION. THEREFORE, VALPROATE SHOULD BE CONSIDERED FOR WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING POTENTIAL ONLY AFTER THE RISKS HAVE BEEN THOROUGHLY DISCUSSED WITH THE PATIENT AND WEIGHED AGAINST THE POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF TREATMENT.

THERE ARE MULTIPLE REPORTS IN THE CLINICAL LITERATURE THAT INDICATE THE USE OF ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS DURING PREGNANCY RESULTS IN AN INCREASED INCIDENCE OF CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS IN OFFSPRING. ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS, INCLUDING VALPROATE, SHOULD BE ADMINISTERED TO WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING POTENTIAL ONLY IF THEY ARE CLEARLY SHOWN TO BE ESSENTIAL IN THE MANAGEMENT OF THEIR MEDICAL CONDITION.

Antiepileptic drugs should not be discontinued abruptly in patients in whom the drug is administered to prevent major seizures because of the strong possibility of precipitating status epilepticus with attendant hypoxia and threat to life. In individual cases where the severity and frequency of the seizure disorder are such that the removal of medication does not pose a serious threat to the patient, discontinuation of the drug may be considered prior to and during pregnancy, although it cannot be said with any confidence that even minor seizures do not pose some hazard to the developing embryo or fetus.

HUMAN DATA

Congenital Malformations

The North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry reported 16 cases of congenital malformations among the offspring of 149 women with epilepsy who were exposed to valproic acid monotherapy during the first trimester of pregnancy at doses of approximately 1,000 mg per day, for a prevalence rate of 10.7% (95% CI 6.3% to 16.9%). Three of the 149 offspring (2%) had neural tube defects and 6 of the 149 (4%) had less severe malformations. Among epileptic women who were exposed to other antiepileptic drug monotherapies during pregnancy (1,048 patients) the malformation rate was 2.9% (95% CI 2% to 4.1%). There was a 4 fold increase in congenital malformations among infants with valproic acid-exposed mothers compared with those treated with other antiepileptic monotherapies as a group (Odds Ratio 4; 95% CI 2.1 to 7.4). This increased risk does not reflect a comparison versus any specific antiepileptic drug, but the risk versus the heterogeneous group of all other antiepileptic drug monotherapies combined. The increased teratogenic risk from valproic acid in women with epilepsy is expected to be reflected in an increased risk in other indications (e.g., migraine or bipolar disorder).

THE STRONGEST ASSOCIATION OF MATERNAL VALPROATE USAGE WITH CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS IS WITH NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS (AS DISCUSSED UNDER THE NEXT SUBHEADING). HOWEVER, OTHER CONGENITAL ANOMALIES (E.G. CRANIOFACIAL DEFECTS, CARDIOVASCULAR MALFORMATIONS AND ANOMALIES INVOLVING VARIOUS BODY SYSTEMS), COMPATIBLE AND INCOMPATIBLE WITH LIFE, HAVE BEEN REPORTED. SUFFICIENT DATA TO DETERMINE THE INCIDENCE OF THESE CONGENITAL ANOMALIES IS NOT AVAILABLE.

Neural Tube Defects

THE INCIDENCE OF NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS IN THE FETUS IS INCREASED IN MOTHERS RECEIVING VALPROATE DURING THE FIRST TRIMESTER OF PREGNANCY. THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL (CDC) HAS ESTIMATED THE RISK OF VALPROIC ACID EXPOSED WOMEN HAVING CHILDREN WITH SPINA BIFIDA TO BE APPROXIMATELY 1 TO 2%. THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF OBSTETRICIANS AND GYNECOLOGISTS (ACOG) ESTIMATES THE GENERAL POPULATION RISK FOR CONGENITAL NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS AS 0.14% TO 0.2%.

Tests to detect neural tube and other defects using current accepted procedures should be considered a part of routine prenatal care in pregnant women receiving valproate.

Evidence suggests that pregnant women who receive folic acid supplementation may be at decreased risk for congenital neural tube defects in their offspring compared to pregnant women not receiving folic acid. Whether the risk of neural tube defects in the offspring of women receiving valproate specifically is reduced by folic acid supplementation is unknown. DIETARY FOLIC ACID SUPPLEMENTATION BOTH PRIOR TO AND DURING PREGNANCY SHOULD BE ROUTINELY RECOMMENDED TO PATIENTS CONTEMPLATING PREGNANCY.

Other Adverse Pregnancy Effects

PATIENTS TAKING VALPROATE MAY DEVELOP CLOTTING ABNORMALITIES (SEE PRECAUTIONS - GENERAL AND WARNINGS). A PATIENT WHO HAD LOW FIBRINOGEN WHEN TAKING MULTIPLE ANTICONVULSANTS INCLUDING VALPROATE GAVE BIRTH TO AN INFANT WITH AFIBRINOGENEMIA WHO SUBSEQUENTLY DIED OF HEMORRHAGE. IF VALPROATE IS USED IN PREGNANCY, THE CLOTTING PARAMETERS SHOULD BE MONITORED CAREFULLY.

PATIENTS TAKING VALPROATE MAY DEVELOP HEPATIC FAILURE (SEE WARNINGS - HEPATOTOXICITY AND BOX WARNING). FATAL HEPATIC FAILURES, IN A NEWBORN AND IN AN INFANT, HAVE BEEN REPORTED FOLLOWING THE MATERNAL USE OF VALPROATE DURING PREGNANCY.

ANIMAL DATA

Animal studies have demonstrated valproate-induced teratogenicity. Increased frequencies of malformations, as well as intrauterine growth retardation and death, have been observed in mice, rats, rabbits, and monkeys following prenatal exposure to valproate. Malformations of the skeletal system are the most common structural abnormalities produced in experimental animals, but neural tube closure defects have been seen in mice exposed to maternal plasma valproate concentrations exceeding 230 mcg/mL (2.3 times the upper limit of the human therapeutic range) during susceptible periods of embryonic development. Administration of an oral dose of 200 mg/kg/day or greater (50% of the maximum human daily dose or greater on a mg/m2 basis) to pregnant rats during organogenesis produced malformations (skeletal, cardiac, and urogenital) and growth retardation in the offspring. These doses resulted in peak maternal plasma valproate levels of approximately 340 mcg/mL or greater (3.4 times the upper limit of the human therapeutic range or greater). Behavioral deficits have been reported in the offspring of rats given a dose of 200 mg/kg/day throughout most of pregnancy. An oral dose of 350 mg/kg/day (approximately 2 times the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis) produced skeletal and visceral malformations in rabbits exposed during organogenesis. Skeletal malformations, growth retardation, and death were observed in rhesus monkeys following administration of an oral dose of 200 mg/kg/day (equal to the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis) during organogenesis. This dose resulted in peak maternal plasma valproate levels of approximately 280 mcg/mL (2.8 times the upper limit of the human therapeutic range).

-

PRECAUTIONS

Hyperammonemia

Hyperammonemia has been reported in association with valproate therapy and may be present despite normal liver function tests. In patients who develop unexplained lethargy and vomiting or changes in mental status, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured. If ammonia is increased, valproate therapy should be discontinued. Appropriate interventions for treatment of hyperammonemia should be initiated, and such patients should undergo investigation for underlying urea cycle disorders (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS– Urea Cycle Disorders and PRECAUTIONS - Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy Associated with Concomitant Topiramate Use).

Asymptomatic elevations of ammonia are more common and when present, require close monitoring of plasma ammonia levels. If the elevation persists, discontinuation of valproate therapy should be considered. In patients who develop unexplained lethargy, vomiting, or changes in mental status, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured. (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS - Urea Cycle Disorders and PRECAUTIONS - Hyperammonemia).

Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy Associated with Concomitant Topiramate Use

Concomitant administration of topiramate and valproic acid has been associated with hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy in patients who have tolerated either drug alone. Clinical symptoms of hyperammonemic encephalopathy often include acute alterations in level of consciousness and/or cognitive function with lethargy or vomiting. In most cases, symptoms and signs abated with discontinuation of either drug. This adverse event is not due to a pharmacokinetic interaction. It is not known if topiramate monotherapy is associated with hyperammonemia. Patients with inborn errors of metabolism or reduced hepatic mitochondrial activity may be at an increased risk for hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy. Although not studied, an interaction of topiramate and valproic acid may exacerbate existing defects or unmask deficiencies in susceptible persons. In patients who develop unexplained lethargy, vomiting, or changes in mental status, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured. (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS - Urea Cycle Disorders and PRECAUTIONS - Hyperammonemia)

General

Because of reports of thrombocytopenia (see WARNINGS), inhibition of the secondary phase of platelet aggregation, and abnormal coagulation parameters, (e.g., low fibrinogen), platelet counts and coagulation tests are recommended before initiating therapy and at periodic intervals. It is recommended that patients receiving divalproex sodium be monitored for platelet count and coagulation parameters prior to planned surgery. In a clinical trial of divalproex sodium as monotherapy in patients with epilepsy, 34/126 patients (27%) receiving approximately 50 mg/kg/day on average, had at least one value of platelets ≤ 75 x 109/L. Approximately half of these patients had treatment discontinued, with return of platelet counts to normal. In the remaining patients, platelet counts normalized with continued treatment. In this study, the probability of thrombocytopenia appeared to increase significantly at total valproate concentrations of ≥ 110 mcg/mL (females) or ≥ 135 mcg/mL (males). Evidence of hemorrhage, bruising, or a disorder of hemostasis/coagulation is an indication for reduction of the dosage or withdrawal of therapy.

Since divalproex sodium may interact with concurrently administered drugs which are capable of enzyme induction, periodic plasma concentration determinations of valproate and concomitant drugs are recommended during the early course of therapy. (See PRECAUTIONS - Drug Interactions.)

Valproate is partially eliminated in the urine as a keto-metabolite which may lead to a false interpretation of the urine ketone test.

There have been reports of altered thyroid function tests associated with valproate. The clinical significance of these is unknown.

Suicidal ideation may be a manifestation of certain psychiatric disorders, and may persist until significant remission of symptoms occurs. Close supervision of high risk patients should accompany initial drug therapy.

There are in vitro studies that suggest valproate stimulates the replication of the HIV and CMV viruses under certain experimental conditions. The clinical consequence, if any, is not known. Additionally, the relevance of these in vitro findings is uncertain for patients receiving maximally suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Nevertheless, these data should be borne in mind when interpreting the results from regular monitoring of the viral load in HIV infected patients receiving valproate or when following CMV infected patients clinically.

Multi-organ Hypersensitivity Reaction

Multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions have been rarely reported in close temporal association to the initiation of valproate therapy in adult and pediatric patients (median time to detection 21 days: range 1 to 40 days). Although there have been a limited number of reports, many of these cases resulted in hospitalization and at least one death has been reported. Signs and symptoms of this disorder were diverse; however, patients typically, although not exclusively, presented with fever and rash associated with other organ system involvement. Other associated manifestations may include lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, liver function test abnormalities, hematological abnormalities (e.g., eosinophilia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia), pruritis, nephritis, oliguria, hepatorenal syndrome, arthralgia, and asthenia. Because the disorder is variable in its expression, other organ system symptoms and signs, not noted here, may occur. If this reaction is suspected, valproate should be discontinued and an alternative treatment started. Although the existence of cross sensitivity with other drugs that produce this syndrome is unclear, the experience amongst drugs associated with multi-organ hypersensitivity would indicate this to be a possibility.

Information for Patients

Patients and guardians should be warned that abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or anorexia can be symptoms of pancreatitis and, therefore, require further medical evaluation promptly.

Patients should be informed of the signs and symptoms associated with hyperammonemic encephalopathy (see PRECAUTIONS – Hyperammonemia) and be told to inform the prescriber if any of these symptoms occur.

Since divalproex sodium products may produce CNS depression, especially when combined with another CNS depressant (e.g., alcohol), patients should be advised not to engage in hazardous activities, such as driving an automobile or operating dangerous machinery, until it is known that they do not become drowsy from the drug.

Since divalproex sodium has been associated with certain types of birth defects, female patients of child-bearing age considering the use of divalproex sodium should be advised of the risk and of alternative therapeutic options and to read the Patient Information Leaflet, which appears as the last section of the labeling. This is especially important when the treatment of a spontaneously reversible condition not ordinarily associated with permanent injury or risk of death (e.g., migraine) is considered.

Patients should be instructed that a fever associated with other organ system involvement (rash, lymphadenopathy, etc.) may be drug-related and should be reported to the physician immediately (see PRECAUTIONS - Multi-organ Hypersensitivity Reaction).

Drug Interactions

Effects of Co-Administered Drugs on Valproate Clearance

Drugs that affect the level of expression of hepatic enzymes, particularly those that elevate levels of glucuronosyltransferases, may increase the clearance of valproate. For example, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital (or primidone) can double the clearance of valproate. Thus, patients on monotherapy will generally have longer half-lives and higher concentrations than patients receiving polytherapy with antiepilepsy drugs.

In contrast, drugs that are inhibitors of cytochrome P450 isozymes, e.g., antidepressants, may be expected to have little effect on valproate clearance because cytochrome P450 microsomal mediated oxidation is a relatively minor secondary metabolic pathway compared to glucuronidation and beta-oxidation.

Because of these changes in valproate clearance, monitoring of valproate and concomitant drug concentrations should be increased whenever enzyme inducing drugs are introduced or withdrawn.

The following list provides information about the potential for an influence of several commonly prescribed medications on valproate pharmacokinetics. The list is not exhaustive nor could it be, since new interactions are continuously being reported.

Drugs for which a potentially important interaction has been observed

Aspirin

A study involving the co-administration of aspirin at antipyretic doses (11 to 16 mg/kg) with valproate to pediatric patients (n=6) revealed a decrease in protein binding and an inhibition of metabolism of valproate. Valproate free fraction was increased 4 fold in the presence of aspirin compared to valproate alone. The β-oxidation pathway consisting of 2-E-valproic acid, 3-OH-valproic acid, and 3-keto valproic acid was decreased from 25% of total metabolites excreted on valproate alone to 8.3% in the presence of aspirin. Caution should be observed if valproate and aspirin are to be co-administered.

Felbamate

A study involving the co-administration of 1200 mg/day of felbamate with valproate to patients with epilepsy (n=10) revealed an increase in mean valproate peak concentration by 35% (from 86 to 115 mcg/mL) compared to valproate alone. Increasing the felbamate dose to 2400 mg/day increased the mean valproate peak concentration to 133 mcg/mL (another 16% increase). A decrease in valproate dosage may be necessary when felbamate therapy is initiated.

Drugs for which either no interaction or a likely clinically unimportant interaction has been observed

Antacids

A study involving the co-administration of valproate 500 mg with commonly administered antacids (Maalox, Trisogel, and Titralac - 160 mEq doses) did not reveal any effect on the extent of absorption of valproate.

Chlorpromazine

A study involving the administration of 100 to 300 mg/day of chlorpromazine to schizophrenic patients already receiving valproate (200 mg BID) revealed a 15% increase in trough plasma levels of valproate.

Effects of Valproate on Other Drugs

Valproate has been found to be a weak inhibitor of some P450 isozymes, epoxide hydrase, and glucuronosyltransferases.

The following list provides information about the potential for an influence of valproate coadministration on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of several commonly prescribed medications. The list is not exhaustive, since new interactions are continuously being reported.

Drugs for which a potentially important valproate interaction has been observed

Amitriptyline/Nortriptyline

Administration of a single oral 50 mg dose of amitriptyline to 15 normal volunteers (10 males and 5 females) who received valproate (500 mg BID) resulted in a 21% decrease in plasma clearance of amitriptyline and a 34% decrease in the net clearance of nortriptyline. Rare postmarketing reports of concurrent use of valproate and amitriptyline resulting in an increased amitriptyline level have been received. Concurrent use of valproate and amitriptyline has rarely been associated with toxicity. Monitoring of amitriptyline levels should be considered for patients taking valproate concomitantly with amitriptyline. Consideration should be given to lowering the dose of amitriptyline/nortriptyline in the presence of valproate.

Carbamazepine/carbamazepine-10,11-Epoxide

Serum levels of carbamazepine (CBZ) decreased 17% while that of carbamazepine-10, 11-epoxide (CBZ-E) increased by 45% upon co-administration of valproate and CBZ to epileptic patients.

Clonazepam

The concomitant use of valproic acid and clonazepam may induce absence status in patients with a history of absence type seizures.

Diazepam

Valproate displaces diazepam from its plasma albumin binding sites and inhibits its metabolism. Co-administration of valproate (1500 mg daily) increased the free fraction of diazepam (10 mg) by 90% in healthy volunteers (n=6). Plasma clearance and volume of distribution for free diazepam were reduced by 25% and 20%, respectively, in the presence of valproate. The elimination half-life of diazepam remained unchanged upon addition of valproate.

Ethosuximide

Valproate inhibits the metabolism of ethosuximide. Administration of a single ethosuximide dose of 500 mg with valproate (800 to 1600 mg/day) to healthy volunteers (n=6) was accompanied by a 25% increase in elimination half-life of ethosuximide and a 15% decrease in its total clearance as compared to ethosuximide alone. Patients receiving valproate and ethosuximide, especially along with other anticonvulsants, should be monitored for alterations in serum concentrations of both drugs.

Lamotrigine

In a steady-state study involving 10 healthy volunteers, the elimination half-life of lamotrigine increased from 26 to 70 hours with valproate co-administration (a 165% increase). The dose of lamotrigine should be reduced when co-administered with valproate. Serious skin reactions (such as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) have been reported with concomitant lamotrigine and valproate administration. See lamotrigine package insert for details on lamotrigine dosing with concomitant valproate administration.

Phenobarbital

Valproate was found to inhibit the metabolism of phenobarbital. Co-administration of valproate (250 mg BID for 14 days)with phenobarbital to normal subjects (n=6) resulted in a 50% increase in half-life and a 30% decrease in plasma clearance of phenobarbital (60 mg single-dose). The fraction of phenobarbital dose excreted unchanged increased by 50% in presence of valproate.

There is evidence for severe CNS depression, with or without significant elevations of barbiturate or valproate serum concentrations. All patients receiving concomitant barbiturate therapy should be closely monitored for neurological toxicity. Serum barbiturate concentrations should be obtained, if possible, and the barbiturate dosage decreased, if appropriate.

Primidone, which is metabolized to a barbiturate, may be involved in a similar interaction with valproate.

Phenytoin

Valproate displaces phenytoin from its plasma albumin binding sites and inhibits its hepatic metabolism. Co-administration of valproate (400 mg TID) with phenytoin (250 mg) in normal volunteers (n=7) was associated with a 60% increase in the free fraction of phenytoin. Total plasma clearance and apparent volume of distribution of phenytoin increased 30% in the presence of valproate. Both the clearance and apparent volume of distribution of free phenytoin were reduced by 25%.

In patients with epilepsy, there have been reports of breakthrough seizures occurring with the combination of valproate and phenytoin. The dosage of phenytoin should be adjusted as required by the clinical situation.

Tolbutamide

From in vitro experiments, the unbound fraction of tolbutamide was increased from 20% to 50% when added to plasma samples taken from patients treated with valproate. The clinical relevance of this displacement is unknown.

Topiramate

Concomitant administration of valproic acid and topiramate has been associated with hyperammonemia with and without encephalopathy (see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS - Urea Cycle Disorders and PRECAUTIONS- Hyperammonemia and - Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy Associated with Concomitant Topiramate Use).

Drugs for which either no interaction or a likely clinically unimportant interaction has been observed

Acetaminophen

Valproate had no effect on any of the pharmacokinetic parameters of acetaminophen when it was concurrently administered to three epileptic patients.

Clozapine

In psychotic patients (n=11), no interaction was observed when valproate was coadministered with clozapine.

Lithium

Co-administration of valproate (500 mg BID) and lithium carbonate (300 mg TID) to normal male volunteers (n=16) had no effect on the steady-state kinetics of lithium.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Valproic acid was administered orally to Sprague Dawley rats and ICR (HA/ICR) mice at doses of 80 and 170 mg/kg/day (approximately 10 to 50% of the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis) for two years. A variety of neoplasms were observed in both species. The chief findings were a statistically significant increase in the incidence of subcutaneous fibrosarcomas in high dose male rats receiving valproic acid and a statistically significant dose-related trend for benign pulmonary adenomas in male mice receiving valproic acid. The significance of these findings for humans is unknown.

Mutagenesis

Valproate was not mutagenic in an in vitro bacterial assay (Ames test), did not produce dominant lethal effects in mice, and did not increase chromosome aberration frequency in an in vivo cytogenetic study in rats. Increased frequencies of sister chromatid exchange (SCE) have been reported in a study of epileptic children taking valproate, but this association was not observed in another study conducted in adults. There is some evidence that increased SCE frequencies may be associated with epilepsy. The biological significance of an increase in SCE frequency is not known.

Fertility

Chronic toxicity studies in juvenile and adult rats and dogs demonstrated reduced spermatogenesis and testicular atrophy at oral doses of 400 mg/kg/day or greater in rats (approximately equivalent to or greater than the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis) and 150 mg/kg/day or greater in dogs (approximately 1.4 times the maximum human daily dose or greater on a mg/m2 basis). Segment I fertility studies in rats have shown doses up to 350 mg/kg/day (approximately equal to the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis) for 60 days to have no effect on fertility. THE EFFECT OF VALPROATE ON TESTICULAR DEVELOPMENT AND ON SPERM PRODUCTION AND FERTILITY IN HUMANS IS UNKNOWN.

Nursing Mothers

Valproate is excreted in breast milk. Concentrations in breast milk have been reported to be 1 to 10% of serum concentrations. It is not known what effect this would have on a nursing infant. Consideration should be given to discontinuing nursing when divalproex sodium is administered to a nursing woman.

Pediatric Use

Experience has indicated that pediatric patients under the age of two years are at a considerably increased risk of developing fatal hepatotoxicity, especially those with the aforementioned conditions (see BOXED WARNING). When divalproex sodium is used in this patient group, it should be used with extreme caution and as a sole agent. The benefits of therapy should be weighed against the risks. Above the age of 2 years, experience in epilepsy has indicated that the incidence of fatal hepatotoxicity decreases considerably in progressively older patient groups.

Younger children, especially those receiving enzyme-inducing drugs, will require larger maintenance doses to attain targeted total and unbound valproic acid concentrations.

The variability in free fraction limits the clinical usefulness of monitoring total serum valproic acid concentrations. Interpretation of valproic acid concentrations in children should include consideration of factors that affect hepatic metabolism and protein binding.

The safety and effectiveness of divalproex sodium for the treatment of acute mania has not been studied in individuals below the age of 18 years.

The safety and effectiveness of divalproex sodium for the prophylaxis of migraines has not been studied in individuals below the age of 16 years.

The basic toxicology and pathologic manifestations of valproate sodium in neonatal (4 day old) and juvenile (14 day old) rats are similar to those seen in young adult rats. However, additional findings, including renal alterations in juvenile rats and renal alterations and retinal dysplasia in neonatal rats, have been reported. These findings occurred at 240 mg/kg/day, a dosage approximately equivalent to the human maximum recommended daily dose on a mg/m2 basis. They were not seen at 90 mg/kg, or 40% of the maximum human daily dose on a mg/m2 basis.

Geriatric Use

No patients above the age of 65 years were enrolled in double-blind prospective clinical trials of mania associated with bipolar illness. In a case review study of 583 patients, 72 patients (12%) were greater than 65 years of age. A higher percentage of patients above 65 years of age reported accidental injury, infection, pain, somnolence, and tremor. Discontinuation of valproate was occasionally associated with the latter two events. It is not clear whether these events indicate additional risk or whether they result from preexisting medical illness and concomitant medication use among these patients.

A study of elderly patients with dementia revealed drug related somnolence and discontinuation for somnolence (see WARNINGS–Somnolence in the Elderly). The starting dose should be reduced in these patients, and dosage reductions or discontinuation should be considered in patients with excessive somnolence (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

There is insufficient information available to discern the safety and effectiveness of divalproex sodium for the prophylaxis of migraines in patients over 65.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Mania

The incidence of treatment-emergent events has been ascertained based on combined data from two placebo-controlled clinical trials of divalproex sodium in the treatment of manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder. The adverse events were usually mild or moderate in intensity, but sometimes were serious enough to interrupt treatment. In clinical trials, the rates of premature termination due to intolerance were not statistically different between placebo, divalproex sodium, and lithium carbonate. A total of 4%, 8% and 11% of patients discontinued therapy due to intolerance in the placebo, divalproex sodium, and lithium carbonate groups, respectively.

Table 1 summarizes those adverse events reported for patients in these trials where the incidence rate in the divalproex sodium-treated group was greater than 5% and greater than the placebo incidence, or where the incidence in the divalproex sodium-treated group was statistically significantly greater than the placebo group. Vomiting was the only event that was reported by significantly (p ≤ 0.05) more patients receiving divalproex sodium compared to placebo.

Table 1. Adverse Events Reported by > 5% of Divalproex Sodium-Treated Patients During Placebo- Controlled Trials of Acute Mania* Adverse Event

Divalproex sodium

(n = 89)Placebo

(n = 97)- * The following adverse events occurred at an equal or greater incidence for placebo than for divalproex sodium: back pain, headache, constipation, diarrhea, tremor, and pharyngitis.

Nausea 22% 15% Somnolence 19% 12% Dizziness 12% 4% Vomiting 12% 3% Asthenia 10% 7% Abdominal pain 9% 8% Dyspepsia 9% 8% Rash 6% 3% The following additional adverse events were reported by greater than 1% but not more than 5% of the 89 divalproex sodium-treated patients in controlled clinical trials:

Cardiovascular System

Hypertension, hypotension, palpitations, postural hypotension, tachycardia, vasodilation.

Digestive System

Anorexia, fecal incontinence, flatulence, gastroenteritis, glossitis, periodontal abscess.

Nervous System

Abnormal dreams, abnormal gait, agitation, ataxia, catatonic reaction, confusion, depression, diplopia, dysarthria, hallucinations, hypertonia, hypokinesia, insomnia, paresthesia, reflexes increased, tardive dyskinesia, thinking abnormalities, vertigo.

Migraine

Based on two placebo-controlled clinical trials and their long term extension, divalproex sodium was generally well tolerated with most adverse events rated as mild to moderate in severity. Of the 202 patients exposed to divalproex sodium in the placebo-controlled trials, 17% discontinued for intolerance. This is compared to a rate of 5% for the 81 placebo patients. Including the long term extension study, the adverse events reported as the primary reason for discontinuation by ≥ 1% of 248 divalproex sodium-treated patients were alopecia (6%), nausea and/or vomiting (5%), weight gain (2%), tremor (2%), somnolence (1%), elevated SGOT and/or SGPT (1%), and depression (1%).

Table 2 includes those adverse events reported for patients in the placebo-controlled trials where the incidence rate in the divalproex sodium-treated group was greater than 5% and was greater than that for placebo patients.

Table 2. Adverse Events Reported by > 5% of Divalproex Sodium-Treated Patients During Migraine Placebo-Controlled Trials with a Greater Incidence Than Patients Taking Placebo* Body System Event Divalproex sodium

(N = 202)Placebo

(N = 81)- * The following adverse events occurred in at least 5% of divalproex sodium-treated patients and at an equal or greater incidence for placebo than for divalproex sodium: flu syndrome and pharyngitis.

Gastrointestinal System Nausea 31% 10% Dyspepsia 13% 9% Diarrhea 12% 7% Vomiting 11% 1% Abdominal pain 9% 4% Increased appetite 6% 4% Nervous System Asthenia 20% 9% Somnolence 17% 5% Dizziness 12% 6% Tremor 9% 0% Other Weight gain 8% 2% Back pain 8% 6% Alopecia 7% 1% The following additional adverse events were reported by greater than 1% but not more than 5% of the 202 divalproex sodium-treated patients in the controlled clinical trials:

Digestive System

Anorexia, constipation, dry mouth, flatulence, gastrointestinal disorder (unspecified), and stomatitis.

Epilepsy

Based on a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy for treatment of complex partial seizures, divalproex sodium was generally well tolerated with most adverse events rated as mild to moderate in severity. Intolerance was the primary reason for discontinuation in the divalproex sodium-treated patients (6%), compared to 1% of placebo-treated patients.

Table 3 lists treatment-emergent adverse events which were reported by ≥ 5% of divalproex sodium-treated patients and for which the incidence was greater than in the placebo group, in the placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy for treatment of complex partial seizures. Since patients were also treated with other antiepilepsy drugs, it is not possible, in most cases, to determine whether the following adverse events can be ascribed to divalproex sodium alone, or the combination of divalproex sodium and other antiepilepsy drugs.

Table 3. Adverse Events Reported by ≥ 5% of Patients Treated with Divalproex Sodium During Placebo-Controlled Trial of Adjunctive Therapy for Complex Partial Seizures Body System/Event Divalproex sodium (%)

(n = 77)Placebo (%)

(n = 70)Body as a Whole Headache 31 21 Asthenia 27 7 Fever 6 4 Gastrointestinal System Nausea 48 14 Vomiting 27 7 Abdominal Pain 23 6 Diarrhea 13 6 Anorexia 12 0 Dyspepsia 8 4 Constipation 5 1 Nervous System Somnolence 27 11 Tremor 25 6 Dizziness 25 13 Diplopia 16 9 Amblyopia/Blurred Vision 12 9 Ataxia 8 1 Nystagmus 8 1 Emotional Lability 6 4 Thinking Abnormal 6 0 Amnesia 5 1 Respiratory System Flu Syndrome 12 9 Infection 12 6 Bronchitis 5 1 Rhinitis 5 4 Other Alopecia 6 1 Weight Loss 6 0 Table 4 lists treatment-emergent adverse events which were reported by ≥ 5% of patients in the high dose divalproex sodium group, and for which the incidence was greater than in the low dose group, in a controlled trial of divalproex sodium monotherapy treatment of complex partial seizures. Since patients were being titrated off another antiepilepsy drug during the first portion of the trial, it is not possible, in many cases, to determine whether the following adverse events can be ascribed to divalproex sodium alone, or the combination of divalproex sodium and other antiepilepsy drugs.

Table 4. Adverse Events Reported by ≥ 5% of Patients in the High Dose Group in the Controlled Trial of Divalproex Sodium Monotherapy for Complex Partial Seizures* Body System/Event High Dose (%)

(n = 131)Low Dose (%)

(n = 134)- * Headache was the only adverse event that occurred in ≥ 5% of patients in the high dose group and at an equal or greater incidence in the low dose group.

Body as a Whole Asthenia 21 10 Digestive System Nausea 34 26 Diarrhea 23 19 Vomiting 23 15 Abdominal Pain 12 9 Anorexia 11 4 Dyspepsia 11 10 Hemic/Lymphatic System Thrombocytopenia 24 1 Ecchymosis 5 4 Metabolic/Nutritional Weight Gain 9 4 Peripheral Edema 8 3 Nervous System Tremor 57 19 Somnolence 30 18 Dizziness 18 13 Insomnia 15 9 Nervousness 11 7 Amnesia 7 4 Nystagmus 7 1 Depression 5 4 Respiratory System Infection 20 13 Pharyngitis 8 2 Dyspnea 5 1 Skin and Appendages Alopecia 24 13 Special Senses Amblyopia/Blurred Vision 8 4 Tinnitus 7 1 The following additional adverse events were reported by greater than 1% but less than 5% of the 358 patients treated with divalproex sodium in the controlled trials of complex partial seizures:

Digestive System

Increased appetite, flatulence, hematemesis, eructation, pancreatitis, periodontal abscess.

Other Patient Populations

Adverse events that have been reported with all dosage forms of valproate from epilepsy trials, spontaneous reports, and other sources are listed below by body system.

Gastrointestinal

The most commonly reported side effects at the initiation of therapy are nausea, vomiting, and indigestion. These effects are usually transient and rarely require discontinuation of therapy. Diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and constipation have been reported. Both anorexia with some weight loss and increased appetite with weight gain have also been reported. The administration of delayed-release divalproex sodium may result in reduction of gastrointestinal side effects in some patients.

CNS Effects

Sedative effects have occurred in patients receiving valproate alone but occur most often in patients receiving combination therapy. Sedation usually abates upon reduction of other antiepileptic medication. Tremor (may be dose-related), hallucinations, ataxia, headache, nystagmus, diplopia, asterixis, "spots before eyes", dysarthria, dizziness, confusion, hypesthesia, vertigo, incoordination, and parkinsonism have been reported with the use of valproate. Rare cases of coma have occurred in patients receiving valproate alone or in conjunction with phenobarbital. In rare instances encephalopathy with or without fever has developed shortly after the introduction of valproate monotherapy without evidence of hepatic dysfunction or inappropriately high plasma valproate levels. Although recovery has been described following drug withdrawal, there have been fatalities in patients with hyperammonemic encephalopathy, particularly in patients with underlying urea cycle disorders (see WARNINGS – Urea Cycle Disorders and PRECAUTIONS).

Several reports have noted reversible cerebral atrophy and dementia in association with valproate therapy.

Dermatologic

Transient hair loss, skin rash, photosensitivity, generalized pruritus, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Rare cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported including a fatal case in a 6 month old infant taking valproate and several other concomitant medications. An additional case of toxic epidermal necrosis resulting in death was reported in a 35 year old patient with AIDS taking several concomitant medications and with a history of multiple cutaneous drug reactions. Serious skin reactions have been reported with concomitant administration of lamotrigine and valproate (see PRECAUTIONS - Drug Interactions).

Psychiatric

Emotional upset, depression, psychosis, aggression, hyperactivity, hostility, and behavioral deterioration.

Hematologic

Thrombocytopenia and inhibition of the secondary phase of platelet aggregation may be reflected in altered bleeding time, petechiae, bruising, hematoma formation, epistaxis, and frank hemorrhage (see PRECAUTIONS - General and Drug Interactions). Relative lymphocytosis, macrocytosis, hypofibrinogenemia, leukopenia, eosinophilia, anemia including macrocytic with or without folate deficiency, bone marrow suppression, pancytopenia, aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, and acute intermittent porphyria.

Hepatic

Minor elevations of transaminases (e.g., SGOT and SGPT) and LDH are frequent and appear to be dose-related. Occasionally, laboratory test results include increases in serum bilirubin and abnormal changes in other liver function tests. These results may reflect potentially serious hepatotoxicity (see WARNINGS).

Endocrine

Irregular menses, secondary amenorrhea, breast enlargement, galactorrhea, and parotid gland swelling. Abnormal thyroid function tests (see PRECAUTIONS).

There have been rare spontaneous reports of polycystic ovary disease. A cause and effect relationship has not been established.

Metabolic

Hyperammonemia (see PRECAUTIONS), hyponatremia, and inappropriate ADH secretion.

There have been rare reports of Fanconi's syndrome occurring chiefly in children.

Decreased carnitine concentrations have been reported although the clinical relevance is undetermined.

Hyperglycinemia has occurred and was associated with a fatal outcome in a patient with preexistent nonketotic hyperglycinemia.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Overdosage with valproate may result in somnolence, heart block, and deep coma. Fatalities have been reported; however patients have recovered from valproate levels as high as 2120 mcg/mL.

In overdose situations, the fraction of drug not bound to protein is high and hemodialysis or tandem hemodialysis plus hemoperfusion may result in significant removal of drug. The benefit of gastric lavage or emesis will vary with the time since ingestion. General supportive measures should be applied with particular attention to the maintenance of adequate urinary output.

Naloxone has been reported to reverse the CNS depressant effects of valproate overdosage. Because naloxone could theoretically also reverse the antiepileptic effects of valproate, it should be used with caution in patients with epilepsy.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Mania

Divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets are administered orally. The recommended initial dose is 750 mg daily in divided doses. The dose should be increased as rapidly as possible to achieve the lowest therapeutic dose which produces the desired clinical effect or the desired range of plasma concentrations. In placebo-controlled clinical trials of acute mania, patients were dosed to a clinical response with a trough plasma concentration between 50 and 125 mcg/mL. Maximum concentrations were generally achieved within 14 days. The maximum recommended dosage is 60 mg/kg/day.

There is no body of evidence available from controlled trials to guide a clinician in the longer term management of a patient who improves during divalproex sodium treatment of an acute manic episode. While it is generally agreed that pharmacological treatment beyond an acute response in mania is desirable, both for maintenance of the initial response and for prevention of new manic episodes, there are no systematically obtained data to support the benefits of divalproex sodium in such longer-term treatment. Although there are no efficacy data that specifically address longer-term antimanic treatment with divalproex sodium, the safety of divalproex sodium in long-term use is supported by data from record reviews involving approximately 360 patients treated with divalproex sodium for greater than 3 months.

Epilepsy

Divalproex sodium delayed-release tablets are administered orally. Divalproex sodium is indicated as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in complex partial seizures in adults and pediatric patients down to the age of 10 years, and in simple and complex absence seizures. As the divalproex sodium dosage is titrated upward, concentrations of phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and/or phenytoin may be affected (see PRECAUTIONS - Drug Interactions).

Complex Partial Seizures

For adults and children 10 years of age or older.

Monotherapy (Initial Therapy)

Divalproex sodium has not been systematically studied as initial therapy. Patients should initiate therapy at 10 to 15 mg/kg/day. The dosage should be increased by 5 to 10 mg/kg/week to achieve optimal clinical response. Ordinarily, optimal clinical response is achieved at daily doses below 60 mg/kg/day. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 to 100 mcg/mL). No recommendation regarding the safety of valproate for use at doses above 60 mg/kg/day can be made.

The probability of thrombocytopenia increases significantly at total trough valproate plasma concentrations above 110 mcg/mL in females and 135 mcg/mL in males. The benefit of improved seizure control with higher doses should be weighed against the possibility of a greater incidence of adverse reactions.

Conversion to Monotherapy

Patients should initiate therapy at 10 to 15 mg/kg/day. The dosage should be increased by 5 to 10 mg/kg/week to achieve optimal clinical response. Ordinarily, optimal clinical response is achieved at daily doses below 60 mg/kg/day. If satisfactory clinical response has not been achieved, plasma levels should be measured to determine whether or not they are in the usually accepted therapeutic range (50 to 100 mcg/mL). No recommendation regarding the safety of valproate for use at doses above 60 mg/kg/day can be made. Concomitant antiepilepsy drug (AED) dosage can ordinarily be reduced by approximately 25% every 2 weeks. This reduction may be started at initiation of divalproex sodium therapy, or delayed by 1 to 2 weeks if there is a concern that seizures are likely to occur with a reduction. The speed and duration of withdrawal of the concomitant AED can be highly variable, and patients should be monitored closely during this period for increased seizure frequency.

Adjunctive Therapy