TOPIRAMATE tablet, film coated

Topiramate by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Topiramate by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Blenheim Pharmacal, Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Topiramate Tablets safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Topiramate Tablets.

TOPIRAMATE TABLETS USP for oral use

Initial U.S. Approval: 1996INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Topiramate Tablets USP are an antiepileptic (AED) agent indicated for: (1)

- Monotherapy epilepsy: Initial monotherapy in patients ≥10 years of age with partial onset or primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (1.1)

- Adjunctive therapy epilepsy: Adjunctive therapy for adults and pediatric patients (2 to 16 years of age) with partial onset seizures or primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and in patients ≥2 years of age with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) (1.2)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

See DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, Epilepsy: Adjunctive Therapy Use for additional details (2.1) (2)

Initial Dose Titration Recommended Dose Epilepsy monotherapy: (2)

adults and pediatric patients ≥10 years (2.1) (2)

50 mg/day in two divided doses (2)

The dosage should be increased weekly by increments of 50 mg for the first 4 weeks then 100 mg for weeks 5 to 6. 400 mg/day in two divided doses (2)

Epilepsy adjunctive therapy: adults with partial onset seizures or LGS (2.1) 25 to 50 mg/day The dosage should be increased weekly to an effective dose by increments of 25 to 50 mg. 200-400 mg/day in two divided doses Epilepsy adjunctive therapy: adults with primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (2.1) 25 to 50 mg/day The dosage should be increased weekly to an effective dose by increments of 25 to 50 mg. 400 mg/day in two divided doses Epilepsy adjunctive therapy: pediatric patients with partial onset seizures, primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures or LGS (2.1) (2)

25 mg/day (or less, based on a range of 1 to 3 mg/kg/day) nightly for the first week (2)

The dosage should be increased at 1- or 2-week intervals by increments of 1 to 3 mg/kg/day (administered in two divided doses). Dose titration should be guided by clinical outcome. (2)

5 to 9 mg/kg/day in two divided doses (2)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- Tablets: 25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

None. (4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Acute myopia and secondary angle closure glaucoma: Untreated elevated intraocular pressure can lead to permanent visual loss. The primary treatment to reverse symptoms is discontinuation of topiramate as rapidly as possible (5.1)

- Oligohidrosis and hyperthermia: Monitor decreased sweating and increased body temperature, especially in pediatric patients (5.2)

- Suicidal behavior and ideation: Antiepileptic drugs increase the risk of suicidal behavior or ideation (5.3)

- Metabolic acidosis: Baseline and periodic measurement of serum bicarbonate is recommended. Consider dose eduction or discontinuation of topiramate if clinically appropriate (5.4)

- Cognitive/neuropsychiatric: Topiramate may cause cognitive dysfunction. Patients should use caution when operating machinery including automobiles. Depression and mood problems may occur in epilepsy populations (5.5).

- Fetal Toxicity: Topiramate use during pregnancy can cause cleft lip and/or palate (5.6)

- Withdrawal of AEDs: Withdrawal of topiramate should be done gradually (5.7)

- Hyperammonemia and encephalopathy associated with or without concomitant valproic acid use: Patients with inborn errors of metabolism or reduced mitochondrial activity may have an increased risk of hyperammonemia. Measure ammonia if encephalopathic symptoms occur (5.9)

- Kidney stones: Use with other carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, other drugs causing metabolic acidosis, or in patients on a ketogenic diet should be avoided (5.10)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common (>5% more frequent than placebo or low dose topiramate in monotherapy) adverse reactions in controlled, epilepsy clinical trials were paresthesia, anorexia, weight decrease, fatigue, dizziness, somnolence, nervousness, psychomotor slowing, difficulty with memory, difficulty with concentration/attention, and confusion.

TO REPORT SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, CONTACT GLENMARK GENERICS INC.,USA AT 1(888)721-7115 OR FDA AT 1-800-FDA-1088 OR www.fda.gov/medwatch

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Summary of antiepileptic drug (AED) interactions with topiramate (7.1). - * Plasma concentration increased 25% in some patients, generally those on a twice a day dosing regimen of phenytoin.

- † Is not administered but is an active metabolite of carbamazepine

AED co-administered AED Concentration Topiramate Concentration Phenytoin NC or 25% increase* 48% decrease Carbamazaepine (CBZ) NC 40% decrease CBZ epoxide† NC NE Valproic acid 11% decrease 14% decrease Phenobarbital NC NE Primidone NC NE Lamotrigine NC at TPM doses up to 400mg/day 13% decrease NC = Less than 10% change in plasma concentration (7)

NE = Not Evaluated (7)

- Concomitant administration of valproic acid and topiramate has been associated with hyperammonemia with and without encephalopathy (5.7)

- Oral contraceptives: Decreased contraceptive efficacy and increased breakthrough bleeding should be considered, especially at doses greater than 200 mg/day (7.3)

- Metformin is contraindicated with metabolic acidosis, a possible effect of topiramate (7.4)

- Lithium levels should be monitored when co-administered with high-dose topiramate (7.5)

- Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: monitor the patient for the appearance or worsening of metabolic acidosis (7.6)

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

- Renal Impairment: In renally impaired patients (creatinine clearance less than 70 mL/min/1.73 m2), one half of the adult dose is recommended (2.4)

- Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: Topiramate is cleared by hemodialysis.

- Dosage adjustment is necessary to avoid rapid drops in topiramate plasma concentration during hemodialysis (2.6)

- Pregnancy: Increased risk of cleft lip and/or palate.Pregnancy registry available (8.1)

- Nursing Mothers: Caution should be exercised when administered to a nursing mother (8.3)

- Geriatric Use: Dosage adjustment may be necessary for elderly with impaired renal function (8.5)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 4/2014

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Monotherapy Epilepsy

1.2 Adjunctive Therapy Epilepsy

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Epilepsy

2.4 Patients with Renal Impairment

2.5 Geriatric Patients (Ages 65 Years and Over)

2.6 Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

2.7 Patients with Hepatic Disease

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Acute Myopia and Secondary Angle Closure Glaucoma

5.2 Oligohidrosis and Hyperthermia

5.3 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

5.4 Metabolic Acidosis

5.5 Cognitive/Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions

5.6 Fetal Toxicity

5.7 Withdrawal of Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs)

5.8 Sudden Unexplained Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)

5.9 Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy (Without and With Concomitant Valproic Acid [VPA] Use)

5.10 Kidney Stones

5.11 Paresthesia

5.12 Adjustment of Dose in Renal Failure

5.13 Decreased Hepatic Function

5.14 Monitoring: Laboratory Tests

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Monotherapy Epilepsy

6.2 Adjunctive Therapy Epilepsy

6.3 Incidence in Epilepsy Controlled Clinical Trials – Adjunctive Therapy – Partial Onset Seizures, Primary Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures, and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

6.4 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During Double-Blind Epilepsy Adjunctive Therapy Trials

6.5 Incidence in Study 119 – Add-On Therapy– Adults with Partial Onset Seizures

6.6 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During All Epilepsy Clinical Trials

6.9 Postmarketing and Other Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Antiepileptic Drugs

7.2 CNS Depressants

7.3 Oral Contraceptives

7.4 Metformin

7.5 Lithium

7.6 Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Labor and Delivery

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Race and Gender Effects

8.7 Renal Impairment

8.8 Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

8.9 Women of Childbearing Potential

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

12.4 Special Populations

12.5 Drug-Drug Interactions

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

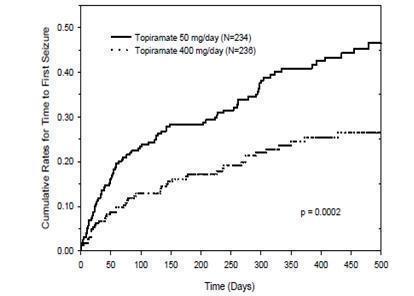

14.1 Monotherapy Epilepsy Controlled Trial

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

Storage and Handling

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

17.1 Eye Disorders

17.2 Oligohydrosis and Hyperthermia

17.3 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

17.4 Metabolic Acidosis

17.5 Interference with Cognitive and Motor Performance

17.6 Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy

17.7 Kidney Stones

17.8 Fetal Toxicity

What is the most important information I should know about topiramate tablets ?

How can I watch for early symptoms of suicidal thoughts and actions?

What is topiramate?

What should I tell my healthcare provider before taking Topiramate Tablets?

How should I take Topiramate Tablets?

What should I avoid while taking topiramate tablets?

What are the possible side effects of topiramate tablets?

How should I store Topiramate tablets ?

What are the ingredients in topiramate tablets USP?

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

-

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Monotherapy Epilepsy

Topiramate Tablets USP are indicated as initial monotherapy in patients 10 years of age and older with partial onset or primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Effectiveness was demonstrated in a controlled trial in patients with epilepsy who had no more than 2 seizures in the 3 months prior to enrollment. Safety and effectiveness in patients who were converted to monotherapy from a previous regimen of other anticonvulsant drugs have not been established in controlled trials [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

1.2 Adjunctive Therapy Epilepsy

Topiramate Tablets USP are indicated as adjunctive therapy for adults and pediatric patients ages 2 to 16 years with partial onset seizures or primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and in patients 2 years of age and older with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Epilepsy

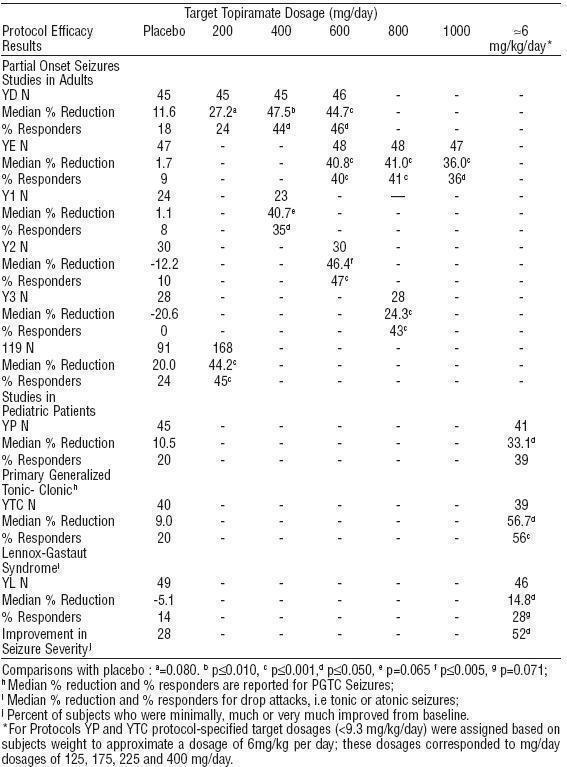

In the controlled adjunctive (i.e., add-on) trials, no correlation has been demonstrated between trough plasma concentrations of topiramate and clinical efficacy. No evidence of tolerance has been demonstrated in humans. Doses above 400 mg/day (600, 800 or 1,000 mg/day) have not been shown to improve responses in dose-response studies in adults with partial onset seizures.

It is not necessary to monitor topiramate plasma concentrations to optimize Topiramate Tablets therapy. On occasion, the addition of Topiramate Tablets USP to phenytoin may require an adjustment of the dose of phenytoin to achieve optimal clinical outcome. Addition or withdrawal of phenytoin and/or carbamazepine during adjunctive therapy with Topiramate Tablets USP may require adjustment of the dose of Topiramate Tablets USP. Because of the bitter taste, tablets should not be broken.

Topiramate Tablets USP can be taken without regard to meals.t

Monotherapy Use

The recommended dose for topiramate monotherapy in adults and pediatric patients 10 years of age and older is 400 mg/day in two divided doses. Approximately 58% of patients randomized to 400 mg/day achieved this maximal dose in the monotherapy controlled trial; the mean dose achieved in the trial was 275 mg/day. The dose should be achieved by titration according to the following schedule:

Morning Dose Evening Dose

Week 1 25mg 25mg Week 2 50mg 50mg Week 3 75mg 75mg Week 4 100mg 100mg Week 5 150mg 150mg Week 6 200mg 200mg Adjunctive Therapy Use

Adults (17 Years of Age and Over) - Partial Onset Seizures, Primary Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures, or Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

The recommended total daily dose of Topiramate Tablets USP as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial onset seizures is 200 to 400 mg/day in two divided doses, and 400 mg/day in two divided doses as adjunctive treatment in adults with primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. It is recommended that therapy be initiated at 25 to 50 mg/day followed by titration to an effective dose in increments of 25 to 50 mg/day every week. Titrating in increments of 25 mg/day every week may delay the time to reach an effective dose. Daily doses above 1,600 mg have not been studied.

In the study of primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures the initial titration rate was slower than in previous studies; the assigned dose was reached at the end of 8 weeks. [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]

Pediatric Patients (Ages 2 - 16 Years) – Partial Onset Seizures, Primary Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures, or Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

The recommended total daily dose of Topiramate Tablets USP as adjunctive therapy for pediatric patients with partial onset seizures, primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is approximately 5 to 9 mg/kg/day in two divided doses. Titration should begin at 25 mg/day (or less, based on a range of 1 to 3 mg/kg/day) nightly for the first week. The dosage should then be increased at 1- or 2 week intervals by increments of 1 to 3 mg/kg/day (administered in two divided doses), to achieve optimal clinical response. Dose titration should be guided by clinical outcome.

In the study of primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures the initial titration rate was slower than in previous studies; the assigned dose of 6 mg/kg/day was reached at the end of 8 weeks [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]

2.4 Patients with Renal Impairment

In renally impaired subjects (creatinine clearance less than 70 mL/min/1.73 m2), one-half of the usual adult dose is recommended. Such patients will require a longer time to reach steady-state at each dose.

2.5 Geriatric Patients (Ages 65 Years and Over)

Dosage adjustment may be indicated in the elderly patient when impaired renal function (creatinine clearance rate <70 mL/min/1.73 m2) is evident [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.6 Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Topiramate is cleared by hemodialysis at a rate that is 4 to 6 times greater than a normal individual. Accordingly, a prolonged period of dialysis may cause topiramate concentration to fall below that required to maintain an anti-seizure effect. To avoid rapid drops in topiramate plasma concentration during hemodialysis, a supplemental dose of topiramate may be required. The actual adjustment should take into account 1) the duration of dialysis period, 2) the clearance rate of the dialysis system being used, and 3) the effective renal clearance of topiramate in the patient being dialyzed.

-

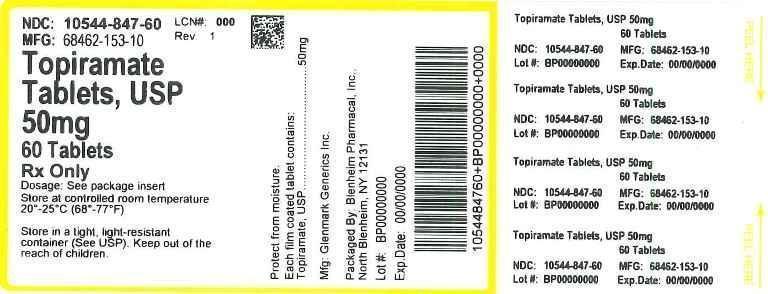

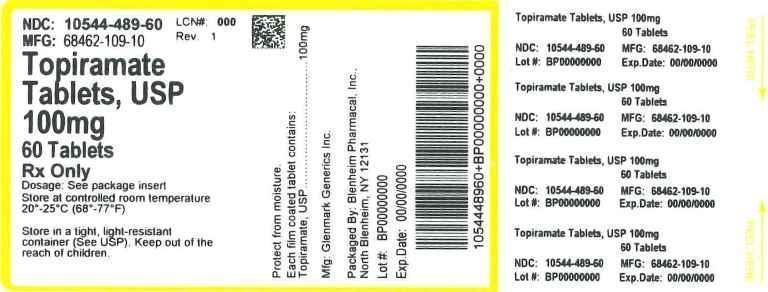

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Topiramate Tablets USP are available as circular, biconvex, film coated, tablets in the following strengths and colors:

25 mg white (engraved “G” on one side; “25” on the other)

50 mg yellow (engraved “G” on one side; “50” on the other)

100 mg yellow (engraved “G” on one side; “100” on the other)

200 mg pink (engraved “G” on one side; “200” on the other)

- 4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Acute Myopia and Secondary Angle Closure Glaucoma

A syndrome consisting of acute myopia associated with secondary angle closure glaucoma has been reported in patients receiving topiramate. Symptoms include acute onset of decreased visual acuity and/or ocular pain. Ophthalmologic findings can include myopia, anterior chamber shallowing, ocular hyperemia (redness) and increased intraocular pressure. Mydriasis may or may not be present.

This syndrome may be associated with supraciliary effusion resulting in anterior displacement of the lens and iris, with secondary angle closure glaucoma. Symptoms typically occur within 1 month of initiating topiramate therapy. In contrast to primary narrow angle glaucoma, which is rare under 40 years of age, secondary angle closure glaucoma associated with topiramate has been reported in pediatric patients as well as adults. The primary treatment to reverse symptoms is discontinuation of topiramate as rapidly as possible, according to the judgment of the treating physician. Other measures, in conjunction with discontinuation of topiramate, may be helpful.

Elevated intraocular pressure of any etiology, if left untreated, can lead to serious sequelae including permanent vision loss.

5.2 Oligohidrosis and Hyperthermia

Oligohidrosis (decreased sweating), infrequently resulting in hospitalization, has been reported in association with topiramate use. Decreased sweating and an elevation in body temperature above normal characterized these cases. Some of the cases were reported after exposure to elevated environmental temperatures.

The majority of the reports have been in pediatric patients. Patients, especially pediatric patients, treated with topiramate should be monitored closely for evidence of decreased sweating and increased body temperature, especially in hot weather. Caution should be used when topiramate is prescribed with other drugs that predispose patients to heat-related disorders; these drugs include, but are not limited to, other carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and drugs with anticholinergic activity.

5.3 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including topiramate, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI:1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5 to 100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed.

Table 1 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 1: Risk by Indication for Antiepileptic Drugs in the Pooled Analysis Indication Placebo Patients with Events per 1000 Patients Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients Relative Risk: Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients. Epilepsy 1.0 3.4 3.5 2.4 Psychiatric 5.7 8.5 1.5 2.9 Other 1.0 1.8 1.9 0.9 Tota1 2.4 4.3 1.8 1.9 The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing topiramate or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

5.4 Metabolic Acidosis

Hyperchloremic, non-anion gap, metabolic acidosis (i.e., decreased serum bicarbonate below the normal reference range in the absence of chronic respiratory alkalosis) is associated with topiramate treatment. This metabolic acidosis is caused by renal bicarbonate loss due to the inhibitory effect of topiramate on carbonic anhydrase. Such electrolyte imbalance has been observed with the use of topiramate in placebo-controlled clinical trials and in the post-marketing period. Generally, topiramate-induced metabolic acidosis occurs early in treatment although cases can occur at any time during treatment. Bicarbonate decrements are usually mild-moderate (average decrease of 4 mEq/L at daily doses of 400 mg in adults and at approximately 6 mg/kg/day in pediatric patients); rarely, patients can experience severe decrements to values below 10 mEq/L. Conditions or therapies that predispose patients to acidosis (such as renal disease, severe respiratory disorders, status epilepticus, diarrhea, ketogenic diet or specific drugs) may be additive to the bicarbonate lowering effects of topiramate.

In adults, the incidence of persistent treatment-emergent decreases in serum bicarbonate (levels of <20 mEq/L at two consecutive visits or at the final visit) in controlled clinical trials for adjunctive treatment of epilepsy was 32% for 400 mg/day, and 1% for placebo. Metabolic acidosis has been observed at doses as low as 50 mg/day. The incidence of persistent treatment-emergent decreases in serum bicarbonate in adults in the epilepsy controlled clinical trial for monotherapy was 15% for 50 mg/day and 25% for 400 mg/day. The incidence of a markedly abnormally low serum bicarbonate (i.e., absolute value <17 mEq/L and >5 mEq/L decrease from pretreatment) in the adjunctive therapy trials was 3% for 400 mg/day, and 0% for placebo and in the monotherapy trial was 1% for 50 mg/day and 7% for 400 mg/day. Serum bicarbonate levels have not been systematically evaluated at daily doses greater than 400 mg/day.

In pediatric patients (2-16 years of age), the incidence of persistent treatment-emergent decreases in serum bicarbonate in placebo-controlled trials for adjunctive treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or refractory partial onset seizures was 67% for topiramate (at approximately 6 mg/kg/day), and 10% for placebo. The incidence of a markedly abnormally low serum bicarbonate (i.e., absolute value <17 mEq/L and >5 mEq/L decrease from pretreatment) in these trials was 11% for topiramate and 0% for placebo. Cases of moderately severe metabolic acidosis have been reported in patients as young as 5 months old, especially at daily doses above 5 mg/kg/day.

Although not approved for use in patients under 2 years of age with partial onset seizures, a controlled trial that examined this population revealed that topiramate produced a metabolic acidosis that is notably greater in magnitude than that observed in controlled trials in older children and adults. The mean treatment difference (25 mg/kg/d topiramate-placebo) was -5.9 mEq/L for bicarbonate. The incidence of metabolic acidosis (defined by a serum bicarbonate <20 mEq/L) was 0% for placebo, 30% for 5 mg/kg/d, 50% for 15 mg/kg/d, and 45% for 25 mg/kg/d [see Pediatric Use (8.4)].

In pediatric patients (10 years up to 16 years of age), the incidence of persistent treatment-emergent decreases in serum bicarbonate in the epilepsy controlled clinical trial for monotherapy was 7% for 50 mg/day and 20% for 400 mg/day. The incidence of a markedly abnormally low serum bicarbonate (i.e., absolute value <17 mEq/L and >5 mEq/L decrease from pretreatment) in this trial was 4% for 50 mg/day and 4% for 400 mg/day.

Some manifestations of acute or chronic metabolic acidosis may include hyperventilation, nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia, or more severe sequelae including cardiac arrhythmias or stupor. Chronic, untreated metabolic acidosis may increase the risk for nephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis, and may also result in osteomalacia (referred to as rickets in pediatric patients) and/or osteoporosis with an increased risk for fractures. Chronic metabolic acidosis in pediatric patients may also reduce growth rates. A reduction in growth rate may eventually decrease the maximal height achieved. The effect of topiramate on growth and bone-related sequelae has not been systematically investigated in long-term, placebo-controlled trials. Long-term, open-label treatment of infants/toddlers, with intractable partial epilepsy, for up to 1 year, showed reductions from baseline in Z SCORES for length, weight, and head circumference compared to age and sex-matched normative data, although these patients with epilepsy are likely to have different growth rates than normal infants. Reductions in Z SCORES for length and weight were correlated to the degree of acidosis [see Pediatric Use (8.4)].

Measurement of baseline and periodic serum bicarbonate during topiramate treatment is recommended. If metabolic acidosis develops and persists, consideration should be given to reducing the dose or discontinuing topiramate (using dose tapering). If the decision is made to continue patients on topiramate in the face of persistent acidosis, alkali treatment should be considered.

5.5 Cognitive/Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions most often associated with the use of topiramate were related to the central nervous system and were observed in epilepsy populations. In adults, the most frequent of these can be classified into three general categories: 1) Cognitive-related dysfunction (e.g., confusion, psychomotor slowing, difficulty with concentration/attention, difficulty with memory, speech or language problems, particularly word-finding difficulties); 2) Psychiatric/behavioral disturbances (e.g., depression or mood problems); and 3) Somnolence or fatigue.

Adult Patients

Cognitive-Related Dysfunction

The majority of cognitive-related adverse reactions were mild to moderate in severity, and they frequently occurred in isolation. Rapid titration rate and higher initial dose were associated with higher incidences of these reactions. Many of these reactions contributed to withdrawal from treatment [see Adverse Reactions (6)].

In the add-on epilepsy controlled trials (using rapid titration such as 100-200 mg/day weekly increments), the proportion of patients who experienced one or more cognitive-related adverse reactions was 42% for 200 mg/day, 41% for 400 mg/day, 52% for 600 mg/day, 56% for 800 and 1,000 mg/day, and 14% for placebo. These dose-related adverse reactions began with a similar frequency in the titration or in the maintenance phase, although in some patients the events began during titration and persisted into the maintenance phase. Some patients who experienced one or more cognitive-related adverse reactions in the titration phase had a dose-related recurrence of these reactions in the maintenance phase.

In the monotherapy epilepsy controlled trial, the proportion of patients who experienced one or more cognitive-related adverse reactions was 19% for topiramate tablets 50 mg/day and 26% for 400 mg/day.

Psychiatric/Behavioral Disturbances

Psychiatric/behavioral disturbances (depression or mood) were dose-related for epilepsy populations [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

Somnolence/Fatigue

Somnolence and fatigue were the adverse reactions most frequently reported during clinical trials of topiramate for adjunctive epilepsy. For the adjunctive epilepsy population, the incidence of somnolence did not differ substantially between 200 mg/day and 1,000 mg/day, but the incidence of fatigue was dose-related and increased at dosages above 400 mg/day. For the monotherapy epilepsy population in the 50 mg/day and 400 mg/day groups, the incidence of somnolence was dose-related (9% for the 50 mg/day group and 15% for the 400 mg/day group) and the incidence of fatigue was comparable in both treatment groups (14% each).

Additional nonspecific CNS events commonly observed with topiramate in the add-on epilepsy population include dizziness or ataxia.

Pediatric Patients

In double-blind adjunctive therapy and monotherapy epilepsy clinical studies, the incidences of cognitive/neuropsychiatric adverse reactions in pediatric patients were generally lower than observed in adults. These reactions included psychomotor slowing, difficulty with concentration/attention, speech disorders/related speech problems and language problems. The most frequently reported neuropsychiatric reactions in pediatric patients during adjunctive therapy double-blind studies were somnolence and fatigue. The most frequently reported neuropsychiatric reactions in pediatric patients in the 50 mg/day and 400 mg/day groups during the monotherapy double-blind study were headache, dizziness, anorexia, and somnolence.

No patients discontinued treatment due to any adverse events in the adjunctive epilepsy double-blind trials. In the monotherapy epilepsy double-blind trial, 1 pediatric patient (2%) in the 50 mg/day group and 7 pediatric patients (12%) in the 400 mg/day group discontinued treatment due to any adverse events. The most common adverse reaction associated with discontinuation of therapy was difficulty with concentration/attention; all occurred in the 400 mg/day group.

5.6 Fetal Toxicity

Topiramate can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Data from pregnancy registries indicate that infants exposed to topiramate in utero have an increased risk for cleft lip and/or cleft palate (oral clefts). When multiple species of pregnant animals received topiramate at clinically relevant doses, structural malformations, including craniofacial defects, and reduced fetal weights occurred in offspring[see Use in Special Populations (8.1)].

Consider the benefits and the risks of topiramate when administering this drug in women of childbearing potential, particularly when topiramate is considered for a condition not usually associated with permanent injury or death [see Use in Special Populations (8.9) and Patient Counseling Information (17.8)]. Topiramate should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to a fetus [see Use in Special Populations (8.1)and (8.9)].

5.7 Withdrawal of Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs)

In patients with or without a history of seizures or epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs including topiramate should be gradually withdrawn to minimize the potential for seizures or increased seizure frequency [see Clinical Studies (14)].In situations where rapid withdrawal of topiramate is medically required, appropriate monitoring is recommended.

5.8 Sudden Unexplained Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)

During the course of premarketing development of Topiramate Tablets, 10 sudden and unexplained deaths were recorded among a cohort of treated patients (2796 subject years of exposure). This represents an incidence of 0.0035 deaths per patient year. Although this rate exceeds that expected in a healthy population matched for age and sex, it is within the range of estimates for the incidence of sudden unexplained deaths in patients with epilepsy not receiving topiramate (ranging from 0.0005 for the general population of patients with epilepsy, to 0.003 for a clinical trial population similar to that in the topiramate program, to 0.005 for patients with refractory epilepsy).

5.9 Hyperammonemia and Encephalopathy (Without and With Concomitant Valproic Acid [VPA] Use)

Hyperammonemia/Encephalopathy Without Concomitant Valproic Acid (VPA)

Topiramate treatment has produced hyperammonemia (in some instances dose-related) in clinical investigational programs of adolescents (12 to 16 years) who were treated with topiramate monotherapy (incidence above normal, 22% for placebo, 26% for 50 mg/day, 41% for 100 mg daily) and in very young pediatric patients (1 to 24 months) who were treated with adjunctive topiramate for partial onset epilepsy (8% for placebo, 10% for 5 mg/kg/day, 0% for 15 mg/kg/day, 9% for 25 mg/kg/day). Topiramate is not approved as monotherapy for migraine prophylaxis in adolescent patients or as adjunctive treatment of partial onset seizures in pediatric patients less than 2 years old. In some patients, ammonia was markedly increased (≥ 50% above upper limit of normal). In the adolescent patients, the incidence of markedly increased hyperammonemia was 6% for placebo, 6% for 50 mg, and 12% for 100 mg topiramate daily. The hyperammonemia associated with topiramate treatment occurred with and without encephalopathy in placebo-controlled trials, and in an open-label, extension trial. Dose-related hyperammonemia was also observed in the extension trial in pediatric patients up to 2 years old. Clinical symptoms of hyperammonemic encephalopathy often include acute alterations in level of consciousness and/or cognitive function with lethargy or vomiting.

Hyperammonemia with and without encephalopathy has also been observed in post-marketing reports in patients who were taking topiramate without concomitant valproic acid (VPA).

Hyperammonemia/Encephalopathy With Concomitant Valproic Acid (VPA)

Concomitant administration of topiramate and valproic acid (VPA) has been associated with hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy in patients who have tolerated either drug alone based upon post-marketing reports. Although hyperammonemia may be asymptomatic, clinical symptoms of hyperammonemic encephalopathy often include acute alterations in level of consciousness and/or cognitive function with lethargy or vomiting. In most cases, symptoms and signs abated with discontinuation of either drug. This adverse reaction is not due to a pharmacokinetic interaction.

Although topiramate is not indicated for use in infants/toddlers (1-24 months) VPA clearly produced a dose-related increase in the incidence of treatment-emergent hyperammonemia (above the upper limit of normal, 0% for placebo, 12% for 5 mg/kg/day, 7% for 15 mg/kg/day, 17% for 25 mg/kg/day) in an investigational program. Markedly increased, dose-related hyperammonemia (0% for placebo and 5 mg/kg/day, 7% for 15 mg/kg/day, 8% for 25 mg/kg/day) also occurred in these infants/toddlers. Dose-related hyperammonemia was similarly observed in a long-term, extension trial in these very young, pediatric patients [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

Hyperammonemia with and without encephalopathy has also been observed in post-marketing reports in patients taking topiramate with valproic acid (VPA).

The hyperammonemia associated with topiramate treatment appears to be more common when topiramate is used concomitantly with VPA.

Monitoring for Hyperammonemia

Patients with inborn errors of metabolism or reduced hepatic mitochondrial activity may be at an increased risk for hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy. Although not studied, topiramate treatment or an interaction of concomitant topiramate and valproic acid treatment may exacerbate existing defects or unmask deficiencies in susceptible persons.

In patients who develop unexplained lethargy, vomiting, or changes in mental status associated with any topiramate treatment, hyperammonemic encephalopathy should be considered and an ammonia level should be measured.

5.10 Kidney Stones

A total of 32/2086 (1.5%) of adults exposed to topiramate during its adjunctive epilepsy therapy development reported the occurrence of kidney stones, an incidence about 2 to 4 times greater than expected in a similar, untreated population. In the double-blind monotherapy epilepsy study, a total of 4/319 (1.3%) of adults exposed to topiramate reported the occurrence of kidney stones. As in the general population, the incidence of stone formation among topiramate treated patients was higher in men. Kidney stones have also been reported in pediatric patients. During long-term (up to 1 year) topiramate treatment in an open-label extension study of 284 pediatric patients 124 months old with epilepsy, 7% developed kidney or bladder stones that were diagnosed clinically or by sonogram. Topiramate is not approved for pediatric patients less than 2 years old [see Pediatric Use (8.4)] .

An explanation for the association of topiramate and kidney stones may lie in the fact that topiramate is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., zonisamide, acetazolamide or dichlorphenamide) can promote stone formation by reducing urinary citrate excretion and by increasing urinary pH [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]. The concomitant use of topiramate with any other drug producing metabolic acidosis, or potentially in patients on a ketogenic diet may create a physiological environment that increases the risk of kidney stone formation, and should therefore be avoided.

Increased fluid intake increases the urinary output, lowering the concentration of substances involved in stone formation. Hydration is recommended to reduce new stone formation.

5.11 Paresthesia

Paresthesia (usually tingling of the extremities), an effect associated with the use of other carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, appears to be a common effect of topiramate. Paresthesia was more frequently reported in the monotherapy epilepsy trials trials than in the adjunctive therapy epilepsy trials. In the majority of instances, paresthesia did not lead to treatment discontinuation.

5.12 Adjustment of Dose in Renal Failure

The major route of elimination of unchanged topiramate and its metabolites is via the kidney. Dosage adjustment may be required in patients with reduced renal function.[see Dosage and Administration (2)].

5.13 Decreased Hepatic Function

In hepatically impaired patients, topiramate should be administered with caution as the clearance of topiramate may be decreased.

5.14 Monitoring: Laboratory Tests

Topiramate treatment was associated with changes in several clinical laboratory analytes in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies

Topiramate treatment causes non-anion gap, hyperchloremic, metabolic acidosis manifested by a decrease in serum bicarbonate and an increase in serum chloride. Measurement of baseline and periodic serum bicarbonate during topiramate treatment is recommended [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Controlled trials of adjunctive topiramate treatment of adults for partial onset seizures showed an increased incidence of markedly decreased serum phosphorus (6% topiramate, 2% placebo), markedly increased serum alkaline phosphatase (3% topiramate, 1% placebo), and decreased serum potassium (0.4 % topiramate, 0.1 % placebo). The clinical significance of these abnormalities has not been clearly established.

Changes in several clinical laboratory laboratories (increased creatinine, BUN, alkaline phosphatase, total protein, total eosinophil count and decreased potassium) have been observed in a clinical investigational program in very young (<2 years) pediatric patients who were treated with adjunctive topiramate for partial onset seizures [see Pediatric Use (8.4)].

Topiramate treatment produced a dose-related increased shift in serum creatinine from normal at baseline to an increased value at the end of 4 months treatment in adolescent patients (ages 12-16 years) in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Topiramate treatment with or without concomitant valproic acid (VPA) can cause hyperammonemia with or without encephalopathy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The data described in the following section were obtained using Topiramate Tablets.

6.1 Monotherapy Epilepsy

The adverse reactions in the controlled trial that occurred most commonly in adults in the 400 mg/day group and at a rate higher than the 50 mg/day group were: paresthesia, weight decrease, somnolence, anorexia, dizziness, and difficulty with memory NOS [see Table 2].

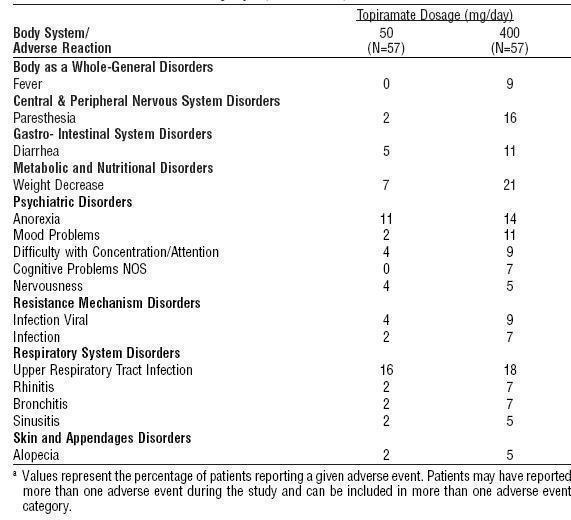

The adverse reactions in the controlled trial that occurred most commonly in children (10 years up to 16 years of age) in the 400 mg/day group and at a rate higher than the 50 mg/day group were: weight decrease, upper respiratory tract infection, paresthesia, anorexia, diarrhea, and mood problems [see Table 3].

Approximately 21% of the 159 adult patients in the 400 mg/day group who received topiramate as monotherapy in the controlled clinical trial discontinued therapy due to adverse reactions. Adverse reactions associated with discontinuing therapy (≥2%) included depression, insomnia, difficulty with memory (NOS), somnolence, paresthesia, psychomotor slowing, dizziness, and nausea.

Approximately 12% of the 57 pediatric patients in the 400 mg/day group who received topiramate as monotherapy in the controlled clinical trial discontinued therapy due to adverse reactions. Adverse reactions associated with discontinuing therapy (≥5%) included difficulty with concentration/attention.

The prescriber should be aware that these data cannot be used to predict the frequency of adverse reactions in the course of usual medical practice where patient characteristics and other factors may differ from those prevailing during the clinical study. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be directly compared with data obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, or investigators. Inspection of these frequencies, however, does provide the prescribing physician with a basis to estimate the relative contribution of drug and non-drug factors to the adverse reactions incidences in the population studied.

Table 2: Incidence of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in the Monotherapy Epilepsy Trial in Adultsa Where Incidence Was at Least 2% in the 400 mg/day Topiramate Group and Greater Than the Rate in the 50 mg/day Topiramate Group

Table 3: Incidence of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in the Monotherapy Epilepsy Trial in Pediatric Patients (Ages 10 up to 16 Years)a Where Incidence Was at Least 5% in the 400 mg/day Topiramate Group and Greater Than the Rate in the 50 mg/day Topiramate Group.

6.2 Adjunctive Therapy Epilepsy

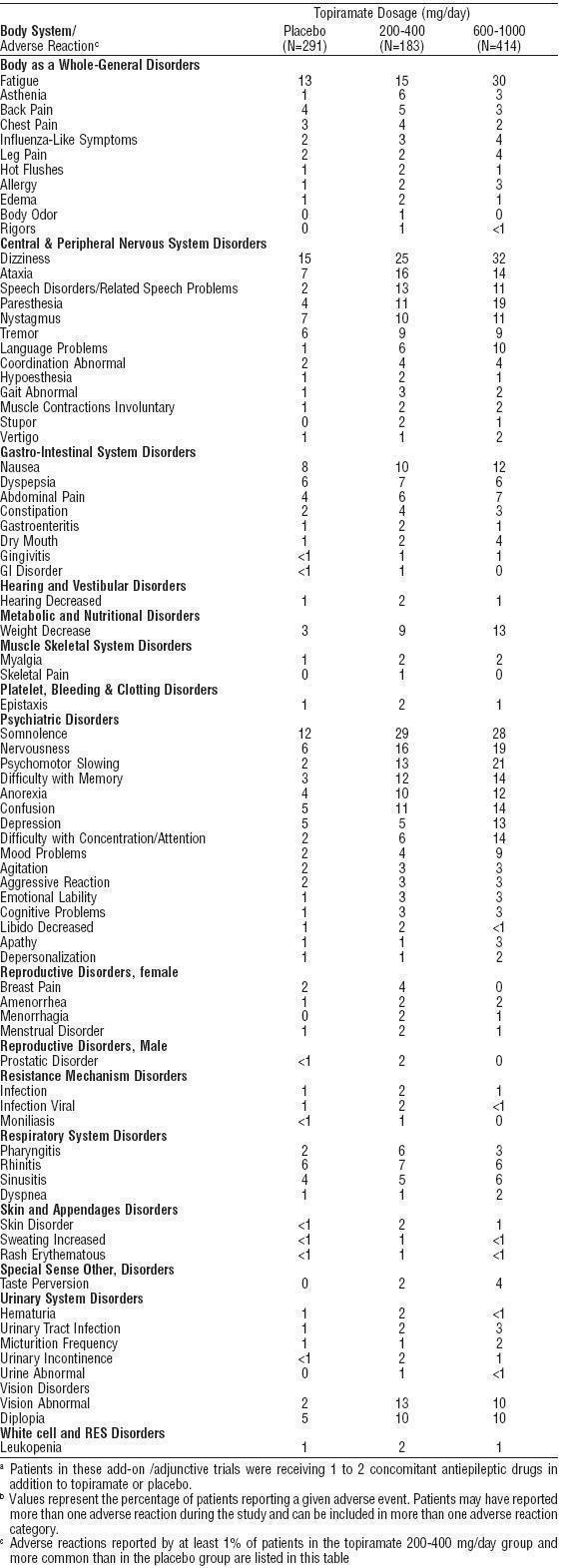

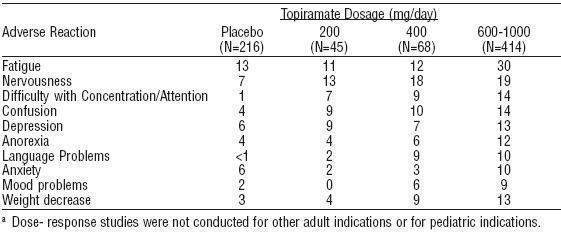

The most commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of topiramate at dosages of 200 to 400 mg/day in controlled trials in adults with partial onset seizures, primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, that were seen at greater frequency in topiramate-treated patients and did not appear to be dose-related were: somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, speech disorders and related speech problems, psychomotor slowing, abnormal vision, difficulty with memory, paresthesia and diplopia [see Table 4]. The most common dose-related adverse reactions at dosages of 200 to 1,000 mg/day were: fatigue, nervousness, difficulty with concentration or attention, confusion, depression, anorexia, language problems, anxiety, mood problems, and weight decrease [see Table 6].

Adverse reactions associated with the use of topiramate at dosages of 5 to 9 mg/kg/day in controlled trials in pediatric patients with partial onset seizures, primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, that were seen at greater frequency in topiramate-treated patients were: fatigue, somnolence, anorexia, nervousness, difficulty with concentration/attention, difficulty with memory, aggressive reaction, and weight decrease [see Table 7].

In controlled clinical trials in adults, 11% of patients receiving topiramate 200 to 400 mg/day as adjunctive therapy discontinued due to adverse reactions. This rate appeared to increase at dosages above 400 mg/day. Adverse events associated with discontinuing therapy included somnolence, dizziness, anxiety, difficulty with concentration or attention, fatigue, and paresthesia and increased at dosages above 400 mg/day. None of the pediatric patients who received topiramate adjunctive therapy at 5 to 9 mg/kg/day in controlled clinical trials discontinued due to adverse reactions.

Approximately 28% of the 1757 adults with epilepsy who received topiramate at dosages of 200 to 1,600 mg/day in clinical studies discontinued treatment because of adverse reactions; an individual patient could have reported more than one adverse reaction. These adverse reactions were: psychomotor slowing (4.0%), difficulty with memory (3.2%), fatigue (3.2%), confusion (3.1%), somnolence (3.2%), difficulty with concentration/attention (2.9%), anorexia (2.7%), depression (2.6%), dizziness (2.5%), weight decrease (2.5%), nervousness (2.3%), ataxia (2.1%), and paresthesia (2.0%). Approximately 11% of the 310 pediatric patients who received topiramate at dosages up to 30 mg/kg/day discontinued due to adverse reactions. Adverse reactions associated with discontinuing therapy included aggravated convulsions (2.3%), difficulty with concentration/attention (1.6%), language problems (1.3%), personality disorder (1.3%), and somnolence (1.3%).

6.3 Incidence in Epilepsy Controlled Clinical Trials – Adjunctive Therapy – Partial Onset Seizures, Primary Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures, and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

Table 4 lists treatment-emergent adverse reactions that occurred in at least 1% of adults treated with 200 to 400 mg/day topiramate in controlled trials that were numerically more common at this dose than in the patients treated with placebo. In general, most patients who experienced adverse reactions during the first eight weeks of these trials no longer experienced them by their last visit. Table 7 lists treatment-emergent adverse reactions that occurred in at least 1% of pediatric patients treated with 5 to 9 mg/kg topiramate in controlled trials that were numerically more common than in patients treated with placebo.

The prescriber should be aware that these data were obtained when topiramate was added to concurrent antiepileptic drug therapy and cannot be used to predict the frequency of adverse reactions in the course of usual medical practice where patient characteristics and other factors may differ from those prevailing during clinical studies. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be directly compared with data obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, or investigators. Inspection of these frequencies, however, does provide the prescribing physician with a basis to estimate the relative contribution of drug and non-drug factors to the adverse reaction incidences in the population studied.

6.4 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During Double-Blind Epilepsy Adjunctive Therapy Trials

Other adverse reactions that occurred in more than 1% of adults treated with 200 to 400 mg of topiramate in placebo-controlled epilepsy trials but with equal or greater frequency in the placebo group were: headache, injury, anxiety, rash, pain, convulsions aggravated, coughing, fever, diarrhea, vomiting, muscle weakness, insomnia, personality disorder, dysmenorrhea, upper respiratory tract infection, and eye pain.

Table 4: Incidence of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in Placebo-Controlled, Add-On Epilepsy Trials in Adultsa,bWhere Incidence Was >1% in Any Topiramate Group and Greater Than the Rate in Placebo-Treated Patients.

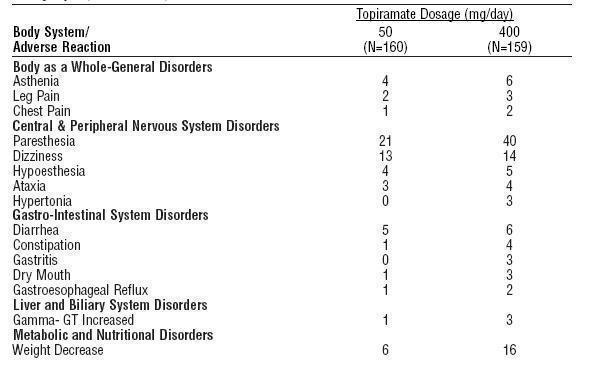

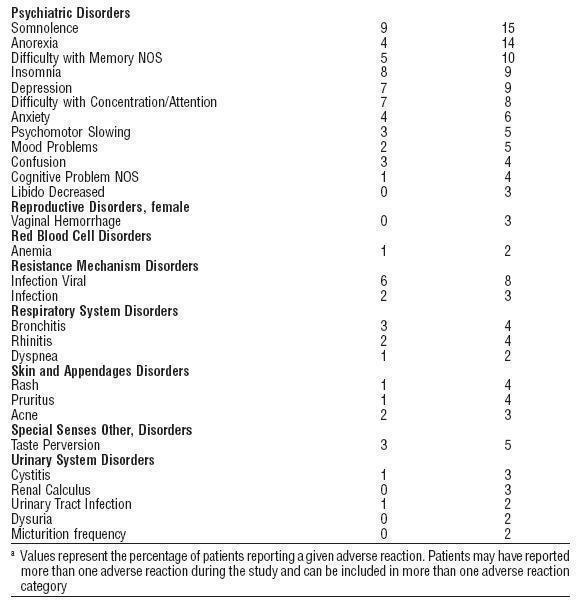

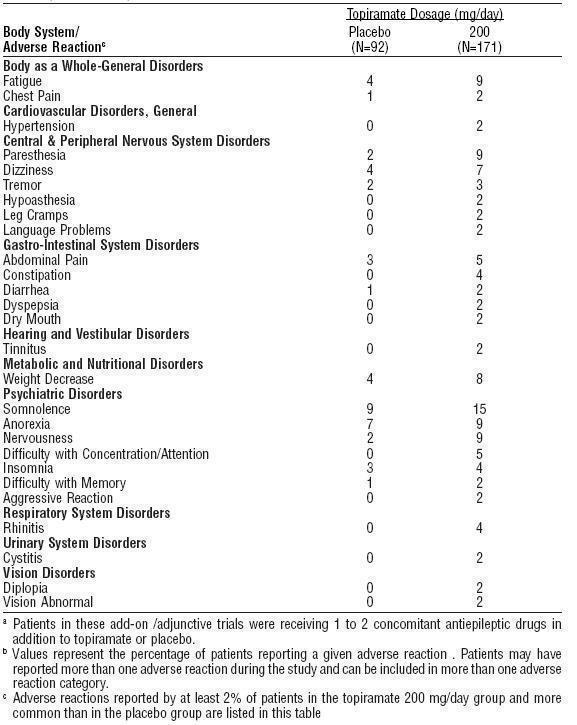

6.5 Incidence in Study 119 – Add-On Therapy– Adults with Partial Onset Seizures

Study 119 was a randomized, double-blind, add-on/adjunctive, placebo-controlled, parallel group study with 3 treatment arms: 1) placebo; 2) topiramate 200 mg/day with a 25 mg/day starting dose, increased by 25 mg/day each week for 8 weeks until the 200 mg/day maintenance dose was reached; and 3) topiramate 200 mg/day with a 50 mg/day starting dose, increased by 50 mg/day each week for 4 weeks until the 200 mg/day maintenance dose was reached. All patients were maintained on concomitant carbamazepine with or without another concomitant antiepileptic drug.

The incidence of adverse reactions (Table 5) did not differ significantly between the 2 topiramate regimens. Because the frequencies of adverse reactions reported in this study were markedly lower than those reported in the previous epilepsy studies, they cannot be directly compared with data obtained in other studies.

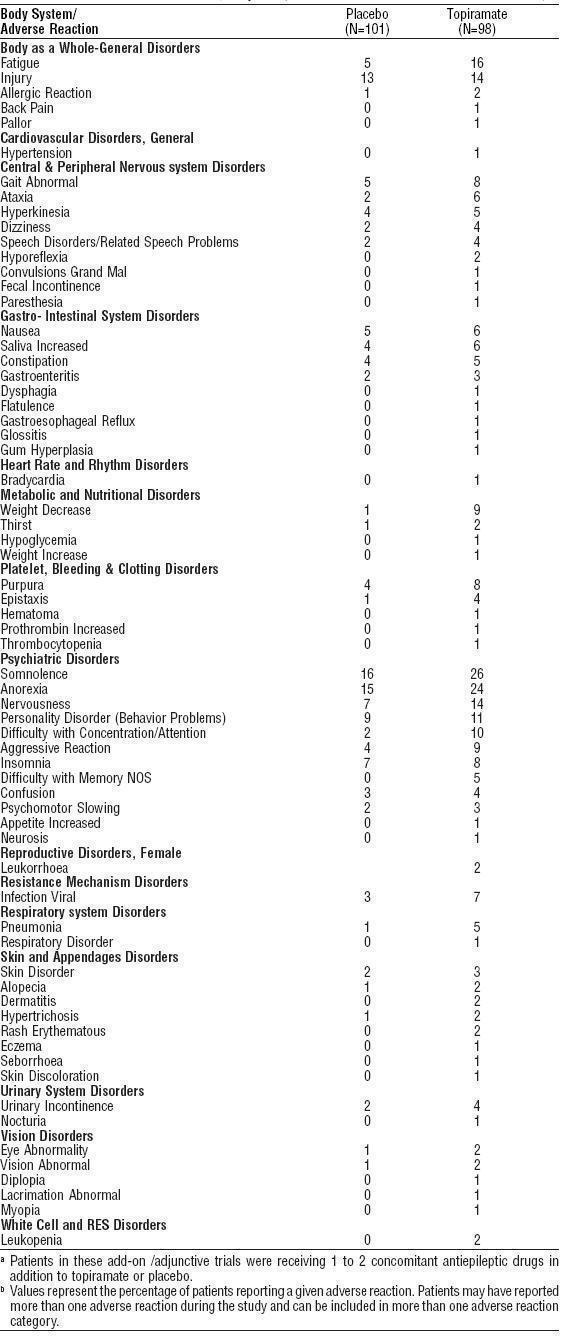

Table 5: Incidence of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in Study 119a,b Where Incidence Was ≥ 2% in the Topiramate Group and Greater Than the Rate in Placebo-Treated Patients.

Table 6: Incidence (%) of Dose-Related Adverse Reactions From Placebo-Controlled, Add-On Trials in Adults with Partial Onset Seizuresa.

Table 7: Incidence (%) of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Reactions in Placebo-Controlled, Add-On Epilepsy Trials in Pediatric Patients (Ages 2 -16 Years)a,b (Reactions that Occurred in at Least 1% of Topiramate-Treated Patients and Occurred More Frequently in Topiramate-Treated Than Placebo-Treated Patients)

6.6 Other Adverse Reactions Observed During All Epilepsy Clinical Trials

Topiramate has been administered to 2246 adults and 427 pediatric patients with epilepsy during all clinical studies, only some of which were placebo-controlled. During these studies, all adverse reactions were recorded by the clinical investigators using terminology of their own choosing. To provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals having adverse reactions, similar types of reactions were grouped into a smaller number of standardized categories using modified WHOART dictionary terminology. The frequencies presented represent the proportion of patients who experienced a reaction of the type cited on at least one occasion while receiving topiramate. Reported reactions are included except those already listed in the previous tables or text, those too general to be informative, and those not reasonably associated with the use of the drug.

Reactions are classified within body system categories and enumerated in order of decreasing frequency using the following definitions: frequent :occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent :occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare:t occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Autonomic Nervous System Disorders:Infrequent: vasodilation

Body as a Whole: Frequent: syncope. Infrequent: abdomen enlarged. Rare: alcohol intolerance

Cardiovascular Disorders, General: Infrequent:hypotension, postural hypotension, angina pectoris.

Central & Peripheral Nervous System Disorders: Infrequent: neuropathy, apraxia, hyperesthesia, dyskinesia, dysphonia, scotoma, ptosis, dystonia, visual field defect, encephalopathy, EEG abnormal. Rare:upper motor neuron lesion, cerebellar syndrome, tongue paralysis

Gastrointestinal System Disorders: Infrequent:hemorrhoids, stomatitis, melena, gastritis, esophagitis. Rare: tongue edema

Heart Rate and Rhythm Disorders: Infrequent:AV block

Liver and Biliary System Disorders: Infrequent: SGPT increased, SGOT increased

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: Infrequent: dehydration, hypocalcemia, hyperlipemia, hyperglycemia, xerophthalmia, diabetes mellitus. Rare: hypernatremia, hyponatremia,hypocholesterolemia, creatinine increased

Musculoskeletal System Disorders: Frequent:tarthralgia. Infrequent: arthrosis

Neoplasms: Infrequent: thrombocythemia. Rare: polycythemia

Platelet, Bleeding, and Clotting Disorders: Infrequent: gingival bleeding, pulmonary embolism.

Psychiatric Disorders: Frequent: impotence, hallucination, psychosis, suicide attempt

Infrequent: euphoria, paranoid reaction, delusion, paranoia, delirium, abnormal dreaming. Rare: libido increased, manic reaction

Red Blood Cell Disorders: Frequent: anemia. Rare: marrow depression, pancytopenia

Reproductive Disorders, Male: Infrequent: ejaculation disorder, breast discharge

Skin and Appendages Disorders: Infrequent: urticaria, photosensitivity reaction, abnormal hair texture. Rare: chloasma

Special Senses Other, Disorders: Infrequent: taste loss, parosmia

Urinary System Disorders: Infrequent: urinary retention, face edema, renal pain, albuminuria, polyuria, oliguria

Vascular (Extracardiac) Disorders: Infrequent: flushing, deep vein thrombosis, phlebitis. Rare: vasospasm

Vision Disorders: Frequent: conjunctivitis. Infrequent: abnormal accommodation, photophobia, strabismus. Rare: mydriasis, iritis

White Cell and Reticuloendothelial System Disorders: Infrequent: lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, lymphopenia, granulocytopenia. Rare: lymphocytosis.

6.9 Postmarketing and Other Experience

In addition to the adverse experiences reported during clinical testing of topiramate, the following adverse experiences have been reported worldwide in patients receiving topiramate post-approval.

These adverse experiences have not been listed above and data are insufficient to support an estimate of their incidence or to establish causation. The listing is alphabetized: bullous skin reactions (including erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis), hepatic failure (including fatalities), hepatitis, maculopathy, pancreatitis, and pemphigus.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

In vitro studies indicate that topiramate does not inhibit enzyme activity for CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4/5 isozymes.In vitro studies indicate that topiramate is a mild inhibitor of CYP2C19 and a mild inducer of CYP3A4. Drug interactions with some antiepileptic drugs, CNS depressants and oral contraceptives are described here. For other drug interactions, please refer to Clinical Pharmacology (12.5).

7.1 Antiepileptic Drugs

Potential interactions between topiramate and standard AEDs were assessed in controlled clinical pharmacokinetic studies in patients with epilepsy. Concomitant administration of phenytoin or carbamazepine with topiramate decreased plasma concentrations of topiramate by 48% and 40% respectively when compared to topiramate given alone [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

In addition, concomitant administration of valproic acid and topiramate has been associated with hyperammonemia with and without encephalopathy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8) or Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

7.2 CNS Depressants

Concomitant administration of topiramate and alcohol or other CNS depressant drugs has not been evaluated in clinical studies. Because of the potential of topiramate to cause CNS depression, as well as other cognitive and/or neuropsychiatric adverse events, topiramate should be used with extreme caution if used in combination with alcohol and other CNS depressants.

7.3 Oral Contraceptives

Exposure to ethinyl estradiol was statistically significantly decreased at doses of 200, 400, and 800 mg/day (18%, 21%, and 30%, respectively) when topiramate was given as adjunctive therapy in patients taking valproic acid). However, norethindrone exposure was not significantly affected. In another pharmacokinetic interaction study in healthy volunteers with a concomitantly administered combination oral contraceptive product containing 1 mg norethindrone (NET) plus 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol (EE), topiramate, given in the absence of other medications at doses of 50 to 200 mg/day, was not associated with statistically significant changes in mean exposure (AUC) to either component of the oral contraceptive. The possibility of decreased contraceptive efficacy and increased breakthrough bleeding should be considered in patients taking combination oral contraceptive products with topiramate. Patients taking estrogen-containing contraceptives should be asked to report any change in their bleeding patterns. Contraceptive efficacy can be decreased even in the absence of breakthrough bleeding [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

7.4 Metformin

Topiramate treatment can frequently cause metabolic acidosis, a condition for which the use of metformin is contraindicated [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

7.5 Lithium

In patients, lithium levels were unaffected during treatment with topiramate at doses of 200 mg/day; however, there was an observed increase in systemic exposure of lithium (27% for Cmax and 26% for AUC) following topiramate doses of up to 600 mg/day. Lithium levels should be monitored when co-administered with high-dose topiramate[see Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

7.6 Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Concomitant use of topiramate, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, with any other carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (e.g., zonisamide, acetazolamide or dichlorphenamide), may increase the severity of metabolic acidosis and may also increase the risk of kidney stone formation. Therefore, if topiramate is given concomitantly with another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, the patient should be monitored for the appearance or worsening of metabolic acidosis [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.5)].

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category D.

[see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

Topiramate can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Data from pregnancy registries indicate that infants exposed to topiramate in utero have an increased risk for cleft lip and/or cleft palate (oral clefts). When multiple species of pregnant animals received topiramate at clinically relevant doses, structural malformations, including craniofacial defects, and reduced fetal weights occurred in offspring. Topiramate should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to a fetus [see Use in Special Populations (8.9)].

Pregnancy Registry

Patients should be encouraged to enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry if they become pregnant. This registry is collecting information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. To enroll, patients can call the toll free number 1888-233-2334. Information about the North American Drug Pregnancy Registry can be found at http://www.massgeneral.org/aed/.

Human Data

Data from the NAAED Pregnancy Registry indicate an increased risk of oral clefts in infants exposed to topiramate monotherapy during the first trimester of pregnancy. The prevalence of oral clefts was 1.4% compared to a prevalence of 0.38% - 0.55% in infants exposed to other AEDs, and a prevalence of 0.07 % in infants of mothers without epilepsy or treatment with other AEDs. For comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reviewed available data on oral clefts in the United States and found a background rate of 0.17%. The relative risk of oral clefts in topiramate-exposed pregnancies in the NAAED Pregnancy Registry was 21.3 (95% Confidence Interval=CI 7.9 – 57.1) as compared to the risk in a background population of untreated women. The UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register reported a similarly increased prevalence of oral clefts of 3.2% among infants exposed to topiramate monotherapy. The observed rate of oral clefts was 16 times higher than the background rate in the UK, which is approximately 0.2%.

Topiramate treatment can cause metabolic acidosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]. The effect of topiramate-induced metabolic acidosis has not been studied in pregnancy; however, metabolic acidosis in pregnancy (due to other causes) can cause decreased fetal growth, decreased fetal oxygenation, and fetal death, and may affect the fetus’ ability to tolerate labor. Pregnant patients should be monitored for metabolic acidosis and treated as in the nonpregnant state see Warnings and Precautions (5.4). Newborns of mothers treated with topiramate should be monitored for metabolic acidosis because of transfer of topiramate to the fetus and possible occurrence of transient metabolic acidosis following birth.

Animal Data

Topiramate has demonstrated selective developmental toxicity, including teratogenicity, in multiple animal species at clinically relevant doses. When oral doses of 20, 100 or 500 mg/kg were administered to pregnant mice during the period of organogenesis, the incidence of fetal malformations (primarily craniofacial defects) was increased at all doses. The low dose is approximately 0.2 times the recommended human dose (RHD) 400 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis. Fetal body weights and skeletal ossification were reduced at 500 mg/kg in conjunction with decreased maternal body weight gain.

In rat studies (oral doses of 20, 100, and 500 mg/kg or 0.2, 2.5, 30, and 400 mg/kg), the frequency of limb malformations (ectrodactyly, micromelia, and amelia) was increased among the offspring of dams treated with 400 mg/kg (10 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) or greater during the organogenesis period of pregnancy. Embryotoxicity (reduced fetal body weights, increased incidence of structural variations) was observed at doses as low as 20 mg/kg (0.5 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis). Clinical signs of maternal toxicity were seen at 400 mg/kg and above, and maternal body weight gain was reduced during treatment with 100 mg/kg or greater.

In rabbit studies (20, 60, and 180 mg/kg or 10, 35, and 120 mg/kg orally during organogenesis), embryo/fetal mortality was increased at 35 mg/kg (2 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) or greater, and teratogenic effects (primarily rib and vertebral malformations) were observed at 120 mg/kg (6 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis). Evidence of maternal toxicity (decreased body weight gain, clinical signs, and/or mortality) was seen at 35 mg/kg and above.

When female rats were treated during the latter part of gestation and throughout lactation (0.2, 4, 20, and 100 mg/kg or 2, 20, and 200 mg/kg), offspring exhibited decreased viability and delayed physical development at 200 mg/kg (5 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) and reductions in pre-and/or postweaning body weight gain at 2 mg/kg (0.05 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) and above. Maternal toxicity (decreased body weight gain, clinical signs) was evident at 100 mg/kg or greater.

In a rat embryo/fetal development study with a postnatal component (0.2, 2.5, 30 or 400 mg/kg during organogenesis; noted above), pups exhibited delayed physical development at 400 mg/kg (10 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) and persistent reductions in body weight gain at 30 mg/kg (1 times the RHD on a mg/m2 basis) and higher.

8.2 Labor and Delivery

Although the effect of topiramate on labor and delivery in humans has not been established, the development of topiramate-induced metabolic acidosis in the mother and/or in the fetus might affect the fetus’ ability to tolerate labor [see Pregnancy (8.1)].

8.3 Nursing Mothers

Limited data on 5 breastfeeding infants exposed to topiramate showed infant plasma topiramate levels equal to 10-20% of the maternal plasma level. The effects of this exposure on infants are unknown. Caution should be exercised when administered to a nursing woman.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Adjunctive Treatment for Partial Onset Epilepsy in Infants and Toddlers (1 to 24 months)

Safety and effectiveness in patients below the age of 2 years have not been established for the adjunctive therapy treatment of partial onset seizures, primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. In a single randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled investigational trial, the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of topiramate oral liquid and sprinkle formulations as an adjunct to concurrent antiepileptic drug therapy in infants 1 to 24 months of age with refractory partial onset seizures were assessed. After 20 days of double-blind treatment, topiramate (at fixed doses of 5, 15, and 25 mg/kg per day) did not demonstrate efficacy compared with placebo in controlling seizures.

In general, the adverse reaction profile in this population was similar to that of older pediatric patients, although results from the above controlled study and an open-label long-term extension study in these infants/toddlers (1 to 24 months old) suggested some adverse reactions/toxicities(not previously observed in older pediatric patients and adults; i.e, growth/length retardation, certain clinical laboratory abnormalities, and other adverse reactions/toxicities that occurred with a greater frequency and/or greater severity than had been recognized previously from studies in older pediatric patients or adults for various indications.

These very young pediatric patients appeared to experience an increased risk for infections (any topiramate dose 12%, placebo 0%) and of respiratory disorders (any topiramate dose 40%, placebo 16%). The following adverse reactions were observed in at least 3% of patients on topiramate and were 3% to 7% more frequent then in patients on placebo: viral infection, bronchitis, pharyngitis, rhinitis, otitis media, upper respiratory infection, cough, and bronchospasm. A generally similar profile was observed in older children [see Adverse Reactions (6)].

Topiramate resulted in an increased incidence of patients with increased creatinine (any topiramate dose 5%, placebo 0%), BUN (any topiramate dose 3%, placebo 0%), and protein (any topiramate dose 34%, placebo 6%), and an increased incidence of decreased potassium (any topiramate dose 7%, placebo 0%). This increased frequency of abnormal values was not dose-related. Creatinine was the only analyte showing a noteworthy increased incidence (topiramate 25 mg/kg/d 5%, placebo 0%) of a markedly abnormal increase [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)]. The significance of these finding is uncertain.

Topiramate treatment also produced a dose-related increase in the percentage of patients who had a shift from normal at baseline to high/increased (above the normal reference range) in total eosinophil count at the end of treatment. The incidence of these abnormal shifts was 6 % for placebo, 10% for 5 mg/kg/d, 9% for 15 mg/kg/d, 14% for 25 mg/kg/d, and 11% for any topiramate dose [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)]. There was a mean dose-related increase in alkaline phosphatase. The significance of these findings is uncertain.

Topiramate produced a dose-related increased incidence of treatment-emergent hyperammonemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Treatment with topiramate for up to 1 year was associated with reductions in Z SCORES for length, weight, and head circumference [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4) and Adverse Reactions (6)].

In open-label, uncontrolled experience, increasing impairment of adaptive behavior was documented in behavioral testing over time in this population. There was a suggestion that this effect was dose-related. However, because of the absence of an appropriate control group, it is not known if this decrement in function was treatment related or reflects the patient’s underlying disease (e.g., patients who received higher doses may have more severe underlying disease) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

In this open-label, uncontrolled study, the mortality was 37 deaths/1000 patient years. It is not possible to know whether this mortality rate is related to topiramate treatment, because the background mortality rate for a similar, significantly refractory, young pediatric population (1-24 months) with partial epilepsy is not known.

Monotherapy Treatment in Partial Onset Epilepsy in Patients <10 Years Old.

Safety and effectiveness in patients below the age of 10 years have not been established for the monotherapy treatment of epilepsy.

Juvenile Animal Studies

When topiramate (30, 90, or 300 mg/kg/day) was administered orally to rats during the juvenile period of development (postnatal days 12 to 50), bone growth plate thickness was reduced in males at the highest dose, which is approximately 5-8 times the maximum recommended pediatric dose (9 mg/kg/day) on a body surface area (mg/m2) basis.

8.5 Geriatric Use

In clinical trials, 3% of patients were over 60. No age-related difference in effectiveness or adverse effects was evident. However, clinical studies of topiramate did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently than younger subjects. Dosage adjustment may be necessary for elderly with impaired renal function (creatinine clearance rate <70 mL/min/1.73 m2) due to reduced clearance of topiramate [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3) and Dosage and Administration (2.5)].

8.6 Race and Gender Effects

Evaluation of effectiveness and safety in clinical trials has shown no race or gender related effects.

8.7 Renal Impairment

The clearance of topiramate was reduced by 42% in moderately renally impaired (creatinine clearance 30 to 69 mL/min/1.73m2) and by 54% in severely renally impaired subjects (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min/1.73m2) compared to normal renal function subjects (creatinine clearance >70 mL/min/1.73m2). One-half the usual starting and maintenance dose is recommended in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment [see Dosage and Administration (2.6) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.4)].

8.8 Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Topiramate is cleared by hemodialysis at a rate that is 4 to 6 times greater than in a normal individual. Accordingly, a prolonged period of dialysis may cause topiramate concentration to fall below that required to maintain an anti-seizure effect. To avoid rapid drops in topiramate plasma concentration during hemodialysis, a supplemental dose of topiramate may be required.

The actual adjustment should take into account the duration of dialysis period, the clearance rate of the dialysis system being used, and the effective renal clearance of topiramate in the patient being dialyzed [see Dosage and Administration (2.4) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.4)].

8.9 Women of Childbearing Potential

Data from pregnancy registries indicate that infants exposed to topiramate in utero have an increased risk for cleft lip and/or cleft palate (oral clefts) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)and Use in Specific Populations (8.1)]. Consider the benefits and the risks of topiramate when prescribing this drug to women of childbearing potential, particularly when topiramate is considered for a condition not usually associated with permanent injury or death. Because of the risk of oral clefts to the fetus, which occur in the first trimester of pregnancy before many women know they are pregnant, all women of childbearing potential should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus from exposure to topiramate. If the decision is made to use topiramate, women who are not planning a pregnancy should use effective contraception [see Drug Interactions (7.3)]. Women who are planning a pregnancy should be counseled regarding the relative risks and benefits of topiramate use during pregnancy, and alternative therapeutic options should be considered for these patients [see Patient Counseling Information (17.8)].

- 9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

Overdoses of topiramate have been reported. Signs and symptoms included convulsions, drowsiness, speech disturbance, blurred vision, diplopia, mentation impaired, lethargy, abnormal coordination, stupor, hypotension, abdominal pain, agitation, dizziness and depression. The clinical consequences were not severe in most cases, but deaths have been reported after poly-drug overdoses involving topiramate.

Topiramate overdose has resulted in severe metabolic acidosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

A patient who ingested a dose between 96 and 110 g topiramate was admitted to a hospital with a coma lasting 20 to 24 hours followed by full recovery after 3 to 4 days.

In acute topiramate overdose, if the ingestion is recent, the stomach should be emptied immediately by lavage or by induction of emesis. Activated charcoal has been shown to adsorb topiramate in vitro. Treatment should be appropriately supportive. Hemodialysis is an effective means of removing topiramate from the body.

-

11 DESCRIPTION

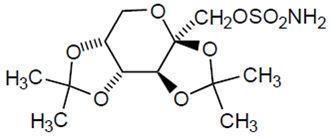

Topiramate is a sulfamate-substituted monosaccharide. Topiramate Tablets USP are available as 25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg round tablets for oral administration.

Topiramate USP is a white crystalline powder with a taste Topiramate USP is most soluble in alkaline solutions containing sodium hydroxide or sodium phosphate and having a pH of 9 to 10. It is freely soluble in acetone, chloroform, dimethylsulfoxide, and ethanol. The solubility in water is 9.8 mg/mL. Its saturated solution has a pH of 6.3. Topiramate USP has the molecular formula C12H21NO8S and a molecular weight of 339.37. Topiramate USP is designated chemically as 2,3:4,5-Di-O-isopropylidene-β-D-fructopyranose sulfamate and has the following structural formula:

Topiramate tablets USP contain the following inactive ingredients: lactose monohydrate, Pregelatinized starch, microcrystalline cellulose, sodium starch glycolate, magnesium stearate, purified water, hypromellose, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol, iron oxide (50,100 and 200 mg tablets) and polysorbate 80.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanisms by which topiramate exerts its anticonvulsant effects are unknown; however, preclinical studies have revealed four properties that may contribute to topiramate's efficacy for epilepsy.. Electrophysiological and biochemical evidence suggests that topiramate, at pharmacologically relevant concentrations, blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels, augments the activity of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyrate at some subtypes of the GABA-A receptor, antagonizes the AMPA/kainate subtype of the glutamate receptor, and inhibits the carbonic anhydrase enzyme, particularly isozymes II and IV.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

Topiramate has anticonvulsant activity in rat and mouse maximal electroshock seizure (MES) tests. Topiramate is only weakly effective in blocking clonic seizures induced by the GABAA receptor antagonist, pentylenetetrazole. Topiramate is also effective in rodent models of epilepsy, which include tonic and absence-like seizures in the spontaneous epileptic rat (SER) and tonic and clonic seizures induced in rats by kindling of the amygdala or by global ischemia.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Absorption of topiramate is rapid, with peak plasma concentrations occurring at approximately 2 hours following a 400 mg oral dose. The relative bioavailability of topiramate from the tablet formulation is about 80% compared to a solution. The bioavailability of topiramate is not affected by food.

The pharmacokinetics of topiramate are linear with dose proportional increases in plasma concentration over the dose range studied (200 to 800 mg/day). The mean plasma elimination half-life is 21 hours after single or multiple doses. Steady state is thus reached in about 4 days in patients with normal renal function. Topiramate is 15% to 41% bound to human plasma proteins over the blood concentration range of 0.5 to 250 μg/mL. The fraction bound decreased as blood concentration increased.

Carbamazepine and phenytoin do not alter the binding of topiramate. Sodium valproate, at 500 μg/mL (a concentration 5 to 10 times higher than considered therapeutic for valproate) decreased the protein binding of topiramate from 23% to 13%. Topiramate does not influence the binding of sodium valproate.

Metabolism and Excretion

Topiramate is not extensively metabolized and is primarily eliminated unchanged in the urine (approximately 70% of an administered dose). Six metabolites have been identified in humans, none of which constitutes more than 5% of an administered dose. The metabolites are formed via hydroxylation, hydrolysis, and glucuronidation. There is evidence of renal tubular reabsorption of topiramate. In rats, given probenecid to inhibit tubular reabsorption, along with topiramate, a significant increase in renal clearance of topiramate was observed. This interaction has not been evaluated in humans. Overall, oral plasma clearance (CL/F) is approximately 20 to 30 mL/min in humans following oral administration.

12.4 Special Populations

Renal Impairment