Isoflurane by Halocarbon Life Sciences, LLC / Pharmasol Corporation ISOFLURANE liquid

Isoflurane by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Isoflurane by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Halocarbon Life Sciences, LLC, Pharmasol Corporation. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

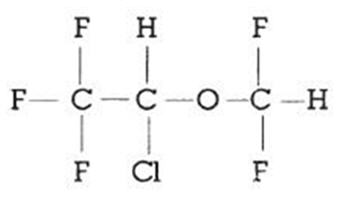

DESCRIPTION

Isoflurane, USP, a nonflammable liquid administered by vaporizing, is a general inhalation anesthetic drug. It is 1-chloro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether, and its structural formula is:

Some physical constants are:

- * Equation for vapor pressure calculation:

Molecular weight 184.5 Boiling point at 760 mm Hg 48.5°C (uncorr.) Refractive index n20D 1.2990-1.3005 Specific gravity 25° / 25°C 1.496 Vapor pressure in mm Hg* 20°C 238 25ºC 295 30°C 367 35°C 450 Log10Pvap = A + B

Twhere: A=8.056

B=-1664.58

T=°C = 273.16 (KelvinPartition coefficients at 37°C:

Water / gas 0.61 Blood / gas 1.43 Oil / gas 90.8 Partition coefficients at 25°C - rubber and plastic

Conductive rubber / gas 62.0 Butyl rubber / gas 75.0 Polyvinyl chloride / gas 110.0 Polyethylene / gas ~2.0 Polyurethane / gas ~1.4 Polyolefin / gas ~1.1 Butyl acetate / gas ~2.5 Purity by gas chromatography >99.9% Lower limit of flammability in oxygen or nitrous oxide at 9 joules/sec. and 23ºC None Lower limit of flammability in oxygen or nitrous oxide at 900 joules/sec. and 23ºC Greater than useful concentration in anesthesia Isoflurane is a clear, colorless, stable liquid containing no additives or chemical stabilizers. Isoflurane has a mildly pungent, musty, ethereal odor. Samples stored in indirect sunlight in clear, colorless glass for five years, as well as samples directly exposed for 30 hours to a 2 amp, 115 volt, 60 cycle long wave U.V. light were unchanged in composition as determined by gas chromatography. Isoflurane in one normal sodium methoxide-methanol solution, a strong base, for over six months consumed essentially no alkali, indicative of strong base stability. Isoflurane does not decompose in the presence of soda lime (at normal operating temperatures), and does not attack aluminum, tin, brass, iron, or copper.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Isoflurane is an inhalation anesthetic. The MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) in man is as follows:

Age 100% Oxygen 70% N2O 26 ± 4 1.28 0.56 44 ± 7 1.15 0.50 64 ± 5 1.05 0.37 Induction of and recovery from isoflurane anesthesia are rapid. Isoflurane has a mild pungency which limits the rate of induction, although excessive salivation or tracheobronchial secretions do not appear to be stimulated. Pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes are readily obtunded. The level of anesthesia may be changed rapidly with isoflurane. Isoflurane is a profound respiratory depressant. RESPIRATION MUST BE MONITORED CLOSELY AND SUPPORTED WHEN NECESSARY. As anesthetic dose is increased, tidal volume decreases and respiratory rate is unchanged. This depression is partially reversed by surgical stimulation, even at deeper levels of anesthesia. Isoflurane evokes a sigh response reminiscent of that seen with diethyl ether and enflurane, although the frequency is less than with enflurane.

Blood pressure decreases with induction of anesthesia but returns toward normal with surgical stimulation. Progressive increases in depth of anesthesia produce corresponding decreases in blood pressure. Nitrous oxide diminishes the inspiratory concentration of isoflurane required to reach a desired level of anesthesia and may reduce the arterial hypotension seen with isoflurane alone. Heart rhythm is remarkably stable. With controlled ventilation and normal PaCO2, cardiac output is maintained despite increasing depth of anesthesia primarily through an increase in heart rate which compensates for a reduction in stroke volume. The hypercapnia which attends spontaneous ventilation during isoflurane anesthesia further increases heart rate and raises cardiac output above awake levels. Isoflurane does not sensitize the myocardium to exogenously administered epinephrine in the dog. Limited data indicate that subcutaneous injection of 0.25mg of epinephrine (50 mL of 1:200,000 solution) does not produce an increase in ventricular arrhythmias in patients anesthetized with isoflurane.

Muscle relaxation is often adequate for intra-abdominal operations at normal levels of anesthesia. Complete muscle paralysis can be attained with small doses of muscle relaxants. ALL COMMONLY USED MUSCLE RELAXANTS ARE MARKEDLY POTENTIATED WITH ISOFLURANE, THE EFFECT BEING MOST PROFOUND WITH THE NONDEPOLARIZING TYPE. Neostigmine reverses the effect of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants in the presence of isoflurane. All commonly used muscle relaxants are compatible with isoflurane.

Isoflurane can produce coronary vasodilation at the arteriolar level in selected animal models; the drug is probably also a coronary dilator in humans. Isoflurane, like some other coronary arteriolar dilators, has been shown to divert blood from collateral dependent myocardium to normally perfused areas in an animal model ("coronary steal"). Clinical studies to date evaluating myocardial ischemia, infarction and death as outcome parameters have not established that the coronary arteriolar dilation property of isoflurane is associated with coronary steal or myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Perioperative Hyperkalemia

Use of inhaled anesthetic agents has been associated with rare increases in serum potassium levels that have resulted in cardiac arrhythmias and death in pediatric patients during the postoperative period. Patients with latent as well as overt neuromuscular disease, particularly Duchenne muscular dystrophy, appear to be most vulnerable. Concomitant use of succinylcholine has been associated with most, but not all, of these cases. These patients also experienced significant elevations in serum creatinine kinase levels and, in some cases, changes in urine consistent with myoglobinuria. Despite the similarity in presentation to malignant hyperthermia, none of these patients exhibited signs or symptoms of muscle rigidity or hypermetabolic state. Early and aggressive intervention to treat the hyperkalemia and resistant arrhythmias is recommended, as is subsequent evaluation for latent neuromuscular disease.

Malignant Hyperthermia

In susceptible individuals, isoflurane anesthesia may trigger a skeletal muscle hypermetabolic state leading to high oxygen demand and the clinical syndrome known as malignant hyperthermia. The syndrome includes nonspecific features such as muscle rigidity, tachycardia, tachypnea, cyanosis, arrhythmias and unstable blood pressure. (It should also be noted that many of these nonspecific signs may appear with light anesthesia, acute hypoxia, etc.) An increase in overall metabolism may be reflected in an elevated temperature (which may rise rapidly early or late in the case, but usually is not the first sign of augmented metabolism) and an increased usage of the CO2 absorption system (hot cannister). PaO2 and pH may decrease, and hyperkalemia and a base deficit may appear. Treatment includes discontinuance of triggering agents (e.g., isoflurane), administration of intravenous dantrolene sodium, and application of supportive therapy. Such therapy includes vigorous efforts to restore body temperature to normal, respiratory and circulatory support as indicated, and management of electrolyte- fluid-acid-base derangements. (Consult prescribing information for dantrolene sodium intravenous for additional information on patient management). Renal failure may appear later, and urine flow should be sustained if possible.

Since levels of anesthesia may be altered easily and rapidly, only vaporizers producing predictable concentrations should be used Hypotension and respiratory depression increase as anesthesia is deepened.

Increased blood loss comparable to that seen with halothane has been observed in patients undergoing abortions.

Isoflurane markedly increases cerebral blood flow at deeper levels of anesthesia. There may be a transient rise in cerebral spinal fluid pressure which is fully reversible with hyperventilation.

Pediatric Neurotoxicity

Published animal studies demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs that block NMDA receptors and/or potentiate GABA activity increase neuronal apoptosis in the developing brain and result in long-term cognitive deficits when used for longer than 3 hours. The clinical significance of these findings is not clear. However, based on the available data, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester of gestation through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately three years of age in humans (See PRECAUTIONS/ Pregnancy, Pediatric Use, and ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY AND/OR PHARMACOLOGY).

Some published studies in children suggest that similar deficits may occur after repeated or prolonged exposures to anesthetic agents early in life and may result in adverse cognitive or behavioral effects. These studies have substantial limitations, and it is not clear if the observed effects are due to the anesthetic/sedation drug administration or other factors such as the surgery or underlying illness.

Anesthetic and sedation drugs are a necessary part of the care of children and pregnant women needing surgery, other procedures, or tests that cannot be delayed, and no specific medications have been shown to be safer than any other. Decisions regarding the timing of any elective procedures requiring anesthesia should take into consideration the benefits of the procedure weighed against the potential risks.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

As with any potent general anesthetic isoflurane should only be administered in an adequately equipped anesthetizing environment by those who are familiar with the pharmacology of the drug and qualified by training and experience to manage the anesthetized patient.

Regardless of the anesthetics employed, maintenance of normal hemodynamics is important to the avoidance of myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease

Isoflurane, like some other inhalational anesthetics, can react with desiccated carbon dioxide (CO2) absorbents to produce carbon monoxide which may result in elevated levels of carboxyhemoglobin in some patients. Case reports suggest that barium hydroxide lime and soda lime become desiccated when fresh gases are passed through the CO2 absorber cannister at high flow rates over many hours or days. When a clinician suspects that CO2 absorbent may be desiccated, it should be replaced before the administration of isoflurane.

As with other halogenated anesthetic agents, isoflurane may cause sensitivity hepatitis in patients who have been sensitized by previous exposure to halogenated anesthetics (see CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Information for Patients

Isoflurane, as well as other general anesthetics, may cause a slight decrease in intellectual function for 2 or 3 days following anesthesia. As with other anesthetics, small changes in moods and symptoms may persist for up to 6 days after administration.

Effect of anesthetic and sedation drugs on early brain development

Studies conducted in young animals and children suggest repeated or prolonged use of general anesthetic or sedation drugs in children younger than 3 years may have negative effects on their developing brains. Discuss with parents and caregivers the benefits, risks, and timing and duration of surgery or procedures requiring anesthetic and sedation drugs (See WARNINGS/Pediatric Neurotoxicity).

Laboratory Tests

Transient increases in BSP retention, blood glucose and serum creatinine with decrease in BUN, serum cholesterol and alkaline phosphatase have been observed.

Drug Interactions

Isoflurane potentiates the muscle relaxant effect of all muscle relaxants, most notably nondepolarizing muscle relaxants, and MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) is reduced by concomitant administration of N2O. See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Swiss ICR mice were given isoflurane to determine whether such exposure might induce neoplasia. Isoflurane was given at 1/2, 1/8 and 1/32 MAC for four in-utero exposures and for 24 exposures to the pups during the first nine weeks of life. The mice were killed at 15 months of age. The incidence of tumors in these mice was the same as in untreated control mice which were given the same background gases, but not the anesthetic.

Mutagenesis

Isoflurane was negative in the in vivo mouse micronucleus and in vitro human lymphocyte chromosomal aberration assay. In published studies, isoflurane was negative in the in vitro bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test) in all strains tested (Salmonella typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, and TA1535) in the presence or absence of metabolic activation.

Pregnancy

Risk Summary

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. In animal reproduction studies, embrofetal toxicity was noted in pregnant mice exposed to 0.075% (increased post implantation losses) and 0.3% isoflurane (increased post implantation losses and decreased live-birth index) during organogenesis.

Published studies in pregnant primates demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs that block NMDA receptors and/or potentiate GABA activity during the period of peak brain development increases neuronal apoptosis in the developing brain of the offspring when used for longer than 3 hours. There are no data on pregnancy exposures in primates corresponding to periods prior to the third trimester in humans [See Data].

The estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2-4% and 15-20%, respectively.

Data

Animal Data

Pregnant rats were exposed to isoflurane at concentrations of 0%, 0.1%, or 0.4% for two hours per day during organogenesis (Gestational Days 6-15). Isoflurane did not cause malformations or clear maternal toxicity under these conditions.

Pregnant mice exposed to isoflurane at concentrations of 0%, 0.075%, or 0.30% for 2 hours per day during organogenesis (Gestational Days 6-15). Isoflurane increased fetal toxicity (higher post implantation losses at 0.075 and 0.3% groups and significantly lower live-birth index in the 0.3% isoflurane treatment group). Isoflurane did not cause malformations or clear maternal toxicity under these conditions.

Pregnant rats were exposed to concentrations of isoflurane at 0%, 0.1%, or 0.4% for 2 hours per day during late gestation (GD 15-20). Animals appeared slightly sedated during exposure. No adverse effects on the offspring or evidence of maternal toxicity were reported. This study did not evaluate neurobehavioral function including learning and memory in the first generation (F1) of pups.

In a published study in primates, administration of an anesthetic dose of ketamine for 24 hours on Gestation Day 122 increased neuronal apoptosis in the developing brain of the fetus. In other published studies, administration of either isoflurane or propofol for 5 hours on Gestation Day 120 resulted in increased neuronal and oligodendrocyte apoptosis in the developing brain of the offspring. With respect to brain development, this time period corresponds to the third trimester of gestation in the human. The clinical significance of these findings is not clear; however, studies in juvenile animals suggest neuroapoptosis correlates with long-term cognitive deficits (See WARNINGS/ Pediatric Neurotoxicity, PRECAUTIONS/ Pediatric Use, and ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY AND/OR PHARMACOLOGY).

Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether this drug is excreted in human milk. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk, caution should be exercised when isoflurane is administered to a nursing woman.

Pediatric Use

Published juvenile animal studies demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs, such as isoflurane, that either block NMDA receptors or potentiate the activity of GABA during the period of rapid brain growth or synaptogenesis, results in widespread neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell loss in the developing brain and alterations in synaptic morphology and neurogenesis. Based on comparisons across species, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester of gestation through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately 3 years of age in humans.

In primates, exposure to 3 hours of ketamine that produced a light surgical plane of anesthesia did not increase neuronal cell loss, however, treatment regimens of 5 hours or longer of isoflurane increased neuronal cell loss. Data from isoflurane-treated rodents and ketamine-treated primates suggest that the neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell losses are associated with prolonged cognitive deficits in learning and memory. The clinical significance of these nonclinical findings is not known, and healthcare providers should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in pregnant women, neonates, and young children who require procedures with the potential risks suggested by the nonclinical data. (See WARNINGS/ Pediatric Neurotoxicity, PRECAUTIONS/ Pregnancy, and ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY AND/OR PHARMACOLOGY).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Adverse reactions encountered in the administration of isoflurane are in general dose dependent extensions of pharmacophysiologic effects and include respiratory depression, hypotension and arrhythmias.

Shivering, nausea, vomiting and ileus have been observed in the postoperative period.

As with all other general anesthetics, transient elevations in white blood count have been observed even in the absence of surgical stress. See WARNINGS for information regarding malignant hyperthermia and elevated carboxyhemoglobin levels. During marketing, there have been rare reports of mild, moderate and severe (some fatal) post-operative hepatic dysfunction and hepatitis.

Isoflurane has also been associated with perioperative hyperkalemia (see WARNINGS).

Post-Marketing Events

The following adverse events have been identified during post-approval use of isoflurane, USP. Due to the spontaneous nature of these reports, the actual incidence and relationship of isoflurane, USP to these events cannot be established with certainty.

Cardiac Disorders: Cardiac arrest

Hepatobiliary Disorders: Hepatic necrosis, Hepatic failure.

- OVERDOSAGE

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Premedication

Premedication should be selected according to the need of the individual patient, taking into account that secretions are weakly stimulated by isoflurane and the heart rate tends to be increased. The use of anticholinergic drugs is a matter of choice.

Inspired Concentration

The concentration of isoflurane being delivered from a vaporizer during anesthesia should be known. This may be accomplished by using:

- a) vaporizers calibrated specifically for isoflurane;

- b) vaporizers from which delivered flows can be calculated, such as vaporizers delivering a saturated vapor which is then diluted. The delivered concentration from such a vaporizer may be calculated using the formula:

% isoflurane = 100 PVFV

–––––––––FT(PA-PV) Where: PA = Pressure of atmosphere PV = Vapor pressure of isoflurane FV = Flow of gas through vaporizer (mL/min) FT = Total gas flow (mL/min) Isoflurane contains no stabilizer. Nothing in the agent alters calibration or operation of these vaporizers.

Induction

Induction with isoflurane in oxygen or in combination with oxygen-nitrous oxide mixtures may produce coughing, breath holding, or laryngospasm. These difficulties may be avoided by the use of a hypnotic dose of an ultra-short-acting barbiturate. Inspired concentrations of 1.5 to 3.0% isoflurane usually produce surgical anesthesia in 7 to 10 minutes.

Maintenance

Surgical levels of anesthesia may be sustained with a 1.0 to 2.5% concentration when nitrous oxide is used concomitantly. An additional 0.5 to 1.0% may be required when isoflurane is given using oxygen alone. If added relaxation is required, supplemental doses of muscle relaxants may be used.

The level of blood pressure during maintenance is an inverse function of isoflurane concentration in the absence of other complicating problems. Excessive decreases may be due to depth of anesthesia and in such instances may be corrected by lightening anesthesia.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Isoflurane, USP is available in unit packages of 100 mL (NDC: 12164-012-10) and 250 mL (NDC: 12164-012-25) amber colored bottles.

Safety and Handling

Occupational Caution

There is no specific work exposure limit established for isoflurane, USP. However, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Administration (NIOSH) recommends that no worker should be exposed at ceiling concentrations greater than 2 ppm of any halogenated anesthetic agent over a sampling period not to exceed one hour.

The predicted effects of acute overexposure by inhalation of isoflurane, USP include headache, dizziness or (in extreme cases) unconsciousness. There are no documented adverse effects of chronic exposure to halogenated anesthetic vapors (Waste Anesthetic Gases or WAGs) in the workplace. Although results of some epidemiological studies suggest a link between exposure to halogenated anesthetics and increased health problems (particularly spontaneous abortion), the relationship is not conclusive. Since exposure to WAGs is one possible factor in the findings for these studies, operating room personnel, and pregnant women in particular, should minimize exposure. Precautions include adequate general ventilation in the operating room, the use of a well-designed and well-maintained scavenging system, work practices to minimize leaks and spills while the anesthetic agent is in use, and routine equipment maintenance to minimize leaks.

-

ANIMAL TOXICOLOGY AND/OR PHARMACOLOGY

Published studies in animals demonstrate that the use of anesthetic agents during the period of rapid brain growth or synaptogenesis results in widespread neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell loss in the developing brain and alterations in synaptic morphology and neurogenesis. Based on comparisons across species, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately 3 years of age in humans.

In primates, exposure to 3 hours of an anesthetic regimen that produced a light surgical plane of anesthesia did not increase neuronal cell loss, however, treatment regimens of 5 hours or longer increased neuronal cell loss. Data in rodents and in primates suggest that the neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell losses are associated with subtle but prolonged cognitive deficits in learning and memory. The clinical significance of these nonclinical findings is not known, and healthcare providers should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in neonates and young children who require procedures against the potential risks suggested by the nonclinical data. (See WARNINGS/ Pediatric Neurotoxicity and PRECAUTIONS/Pregnancy, Pediatric Use)

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 250 mL Bottle Label

NDC: 12164-012-25

250 mLIsoflurane, USP

LIQUID FOR INHALATION

A NONFLAMMABLE, NONEXPLOSIVE, INHALATION

ANESTHETICRx ONLY

Halocarbon

LIFE SCIENCES, LLC1100 Dittman Ct.

North Augusta, SC 29841

www.halocarbon.com

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ISOFLURANE

isoflurane liquidProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 12164-012 Route of Administration RESPIRATORY (INHALATION) Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength Isoflurane (UNII: CYS9AKD70P) (Isoflurane - UNII:CYS9AKD70P) Isoflurane 1 mL in 1 mL Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 12164-012-25 250 mL in 1 BOTTLE, GLASS; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 10/20/1999 2 NDC: 12164-012-10 100 mL in 1 BOTTLE, GLASS; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 10/20/1999 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075225 10/20/1999 Labeler - Halocarbon Life Sciences, LLC (002027514) Registrant - Halocarbon Life Sciences, LLC (109112409) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Halocarbon Life Sciences, LLC 109112409 API MANUFACTURE(12164-012) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Pharmasol Corporation 065144289 PACK(12164-012) , LABEL(12164-012) , ANALYSIS(12164-012)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.