HALOPERIDOL- haloperidol lactate injection

Haloperidol by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Haloperidol by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

Rx only

PREMIERProRx®

WARNING

Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis — Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of seventeen placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10 week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. Haloperidol Injection is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis (see WARNINGS).

-

DESCRIPTION

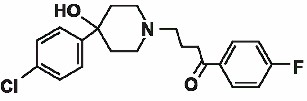

Haloperidol is the first of the butyrophenone series of major antipsychotics. The chemical designation is 4-[4-(p-Chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidino]-4'-fluorobutyrophenone and it has the following structural formula:

Haloperidol Lactate Structural Formula

M.F. =C21H23ClFNO2

M.W.=375.86

Haloperidol Injection, USP is available as a sterile parenteral form for intramuscular injection. Each mL of Haloperidol Injection, USP contains 5 mg haloperidol (as the lactate) with 1.8 mg methylparaben and 0.2 mg propylparaben per mL, and lactic acid for pH adjustment between 3.0 to 3.8.

- CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Haloperidol Injection is contraindicated in patients with:

- Severe toxic central nervous system depression or comatose states from any cause.

- Hypersensitivity to this drug – hypersensitivity reaction shave included anaphylactic reaction and angioedema (see WARNINGS, Hypersensitivity Reactions and ADVERSE REACTIONS).

- Parkinson’s disease (see WARNINGS, Neurological Adverse Reactions in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies).

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (see WARNINGS, Neurological Adverse Reactions in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies).

-

WARNINGS

Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis — Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated withantipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Haloperidol Injection is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis (see BOXED WARNING).

Cardiovascular Effects

Cases of sudden death, QT-prolongation, and Torsades de Pointes have been reported in patients receiving haloperidol. Higher than recommended doses of any formulation and intravenous administration of haloperidol appear to be associated with a higher risk of QT-prolongation and Torsades de Pointes. Although cases have been reported even in the absence of predisposing factors, particular caution is advised in treating patients with other QT-prolonging conditions (including electrolyte imbalance [particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia], drugs known to prolong QT, underlying cardiac abnormalities, hypothyroidism, and familial long QT-syndrome). HALOPERIDOL INJECTION IS NOT APPROVED FOR INTRAVENOUS ADMINISTRATION. If haloperidol is administered intravenously, the ECG should be monitored for QT-prolongation and arrhythmias.

Tardive Dyskinesia

A syndrome consisting of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements may develop in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs (seeADVERSE REACTIONS). Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to rely upon prevalence estimates to predict, at the inception of antipsychotic treatment, which patients are likely to develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

Both the risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible are believed to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose of antipsychotic drugs administered to the patient increase. However, the syndrome can develop, although much less commonly, after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses.

There is no known treatment for established cases of tardive dyskinesia, although the syndrome may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn. Antipsychotic treatment, itself, however, may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome and thereby may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, antipsychotic drugs should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who suffer from a chronic illness that, 1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs, and, 2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient on antipsychotics, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment despite the presence of the syndrome.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with antipsychotic drugs (see ADVERSE REACTIONS). Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status (including catatonic signs) and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmias). Additional signs may include elevated creatine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis) and acute renal failure.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with this syndrome is complicated. In arriving at a diagnosis, it is important to identify cases where the clinical presentation includes both serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection, etc.) and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal signs and symptoms. Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever and primary central nervous system (CNS) pathology.

The management of NMS should include 1) immediate discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs and other drugs not essential to concurrent therapy, 2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring, and 3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for uncomplicated NMS.

If a patient requires antipsychotic drug treatment after recovery from NMS, the potential reintroduction of drug therapy should be carefully considered. The patient should be carefully monitored, since recurrences of NMS have been reported.

Hyperpyrexia and heat stroke, not associated with the above symptom complex, have also been reported with haloperidol.

Neurological Adverse Reactions in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies are reported to have an increased sensitivity to antipsychotic medication. Manifestations of this increased sensitivity with haloperidol treatment include severe extrapyramidal symptoms, confusion, sedation, and falls. In addition, haloperidol may impair the antiparkinson effects of levodopa and other dopamine agonists. Haloperidol is contraindicated in patients with Parkinson’s Disease or Dementia with Lewy Bodies (see CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Hypersensitivity Reactions

There have been postmarketing reports of hypersensitivity reactions with haloperidol. These include anaphylactic reaction, angioedema, dermatitis exfoliative, hypersensitivity vasculitis, rash, urticaria, face edema, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, and laryngospasm (see ADVERSE REACTIONS). Haloperidol is contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to this drug (see CONTRAINDICATIONS).

Falls

Motor instability, somnolence, and orthostatic hypotension have been reported with the use of antipsychotics, including haloperidol, which may lead to falls and, consequently, fractures or other fall-related injuries. for patients, particularly the elderly, with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate these effects, assess the risk of falls when initiating antipsychotic treatment and recurrently for patients receiving repeated doses.

Usage in Pregnancy

Rodents given 2 to 20 times the usual maximum human dose of haloperidol by oral or parenteral routes showed an increase in incidence of resorption, reduced fertility, delayed delivery and pup mortality. No teratogenic effect has been reported in rats, rabbits or dogs at dosages within this range, but cleft palate has been observed in mice given 15 times the usual maximum human dose.

Cleft palate in mice appears to be a nonspecific response to stress or nutritional imbalance as well as to a variety of drugs, and there is no evidence to relate this phenomenon to predictable human risk for most of these agents.

There are no well controlled studies with haloperidol in pregnant women. There are reports, however, of cases of limb malformations observed following maternal use of haloperidol along with other drugs which have suspected teratogenic potential during the first trimester of pregnancy. Causal relationships were not established in these cases. Since such experience does not exclude the possibility of fetal damage due to haloperidol, this drug should be used during pregnancy or in women likely to become pregnant only if the benefit clearly justifies a potential risk to the fetus. Infants should not be nursed during drug treatment.

Non-teratogenic Effects - Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs (including haloperidol) during the third trimester of pregnancy are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery. There have been reports of agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, and feeding disorder in these neonates. These complications have varied in severity; while in some cases symptoms have been self-limited, in other cases neonates have required intensive care unit support and prolonged hospitalization.

Haloperidol should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Combined Use of Haloperidol and Lithium

An encephalopathic syndrome (characterized by weakness, lethargy, fever, tremulousness and confusion, extrapyramidal symptoms, leukocytosis, elevated serum enzymes, BUN, and fasting blood sugar) followed by irreversible brain damage has occurred in a few patients treated with lithium plus haloperidol. A causal relationship between these events and the concomitant administration of lithium and haloperidol has not been established; however, patients receiving such combined therapy should be monitored closely for early evidence of neurological toxicity and treatment discontinued promptly if such signs appear.

General

A number of cases of bronchopneumonia, some fatal, have followed the use of antipsychotic drugs, including haloperidol. It has been postulated that lethargy and decreased sensation of thirst due to central inhibition may lead to dehydration, hemoconcentration and reduced pulmonary ventilation. Therefore, if the above signs and symptoms appear, especially in the elderly, the physician should institute remedial therapy promptly.

Although not reported with haloperidol, decreased serum cholesterol and/or cutaneous and ocular changes have been reported in patients receiving chemically-related drugs.

-

PRECAUTIONS

Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

Class Effect: In clinical trial and/or postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia/neutropenia have been reported temporally related to antipsychotic agents, including Haloperidol Injection. Agranulocytosis has also been reported.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC) and history of drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Patients with a history of a clinically significant low WBC or a drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and discontinuation of Haloperidol Injection should be considered at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors.

Patients with clinically significant neutropenia should be carefully monitored for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treated promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3) should discontinue Haloperidol Injection and have their WBC followed until recovery.

Withdrawal Emergent Dyskinesia

Generally, patients receiving short-term therapy experience no problems with abrupt discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs. However, some patients on maintenance treatment experience transient dyskinetic signs after abrupt withdrawal. In certain of these cases the dyskinetic movements are indistinguishable from tardive dyskinesia (see WARNINGS, Tardive Dyskinesia) except for duration. It is not known whether gradual withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs will reduce the rate of occurrence of withdrawal emergent neurological signs but until further evidence becomes available, it seems reasonable to gradually withdraw use of haloperidol (see WARNINGS, Usage in Pregnancy).

Other

Haloperidol should be administered cautiously to patients:

- with severe cardiovascular disorders, because of the possibility of transient hypotension and/or precipitation of anginal pain. Should hypotension occur and a vasopressor be required, epinephrine should not be used since haloperidol may block its vasopressor activity and paradoxical further lowering of the blood pressure may occur. Instead, metaraminol, phenylephrine or norepinephrine should be used.

- receiving anticonvulsant medications, with a history of seizures, or with EEG abnormalities, because haloperidol may lower the convulsive threshold. If indicated, adequate anticonvulsant therapy should be concomitantly maintained.

- with known allergies, or with a history of allergic reactions to drugs.

- receiving anticoagulants, since an isolated instance of interference occurred with the effects of one anticoagulant (phenindione).

When haloperidol is used to control mania in cyclic disorders, there may be a rapid mood swing to depression.

Severe neurotoxicity (rigidity, inability to walk or talk) may occur in patients with thyrotoxicosis who are also receiving antipsychotic medication, including haloperidol.

Drug Interactions

Drug-drug interactions can be pharmacodynamic (combined pharmacologic effects) or pharmacokinetic (alteration of plasma levels). The risks of using haloperidol in combination with other drugs have been evaluated as described below.

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Since QT-prolongation has been observed during haloperidol treatment, caution is advised when prescribing to a patient with QT-prolongation conditions (long QT-syndrome, hypokalemia, electrolyte imbalance) or to patients receiving medications known to prolong the QT-interval or known to cause electrolyte imbalance.

Haloperidol may impair the antiparkinson effects of levodopa and other dopamine agonists. If concomitant antiparkinson medication is required, it may have to be continued after haloperidol is discontinued because of the difference in excretion rates. If both are discontinued simultaneously, extrapyramidal symptoms may occur. The physician should keep in mind the possible increase in intraocular pressure when anticholinergic drugs, including antiparkinson agents, are administered concomitantly with haloperidol.

As with other antipsychotic agents, it should be noted that haloperidol may be capable of potentiating CNS depressants such as anesthetics, opiates and alcohol.

Ketoconazole is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4. Increases in QTc have been observed when haloperidol was given in combination with the metabolic inhibitors ketoconazole (400 mg/day) and paroxetine (20 mg/day). It may be necessary to reduce the haloperidol dosage.

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

The Effect of Other Drugs on Haloperidol

Haloperidol is metabolized by several routes, including the glucuronidation and the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. Inhibition of these routes of metabolism by another drug may result in increased haloperidol concentrations and potentially increase the risk of certain adverse events, including QT-prolongation.

Drugs Characterized as Substrates, Inhibitors or Inducers of CYP3A4, CYP2D6 or Glucuronidation

In pharmacokinetic studies, mild to moderately increased haloperidol concentrations have been reported when haloperidol was given concomitantly with drugs characterized as substrates or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or CYP2D6 isoenzymes, such as; itraconazole, nefazodone, buspirone, venlafaxine, alprazolam, fluvoxamine, quinidine, fluoxetine, sertraline, chlorpromazine, and promethazine.

Haloperidol is an inhibitor of CYP2D6. Plasma concentrations of CYP2D6 substrates (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants such as desipramine or imipramine) may increase when they are co-administered with haloperidol.

When prolonged treatment (1 to 2 weeks) with enzyme-inducing drugs such as rifampin or carbamazepine is added to haloperidol therapy, this results in a significant reduction of haloperidol plasma levels.

Rifampin

In a study of 12 schizophrenic patients coadministered oral haloperidol and rifampin, plasma haloperidol levels were decreased by a mean of 70% and mean scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale were increased from baseline. In 5 other schizophrenic patients treated with haloperidol and rifampin, discontinuation of rifampin produced a mean 3.3-fold increase in haloperidol concentrations.

Carbamazepine

In a study in 11 schizophrenic patients co-administered haloperidol and increasing doses of carbamazepine, haloperidol plasma concentrations decreased linearly with increasing carbamazepine concentrations.

Thus, careful monitoring of clinical status is warranted when enzyme inducing drugs such as rifampin or carbamazepine are administered or discontinued in haloperidol-treated patients. During combination treatment, the haloperidol dose should be adjusted, when necessary. After discontinuation of such drugs, it may be necessary to reduce the dosage of haloperidol.

Valproate

Sodium valproate, a drug known to inhibit glucuronidation, does not affect haloperidol plasma concentrations.

Information for Patients

Haloperidol may impair the mental and/or physical abilities required for the performance of hazardous tasks such as operating machinery or driving a motor vehicle. The ambulatory patient should be warned accordingly.

The use of alcohol with this drug should be avoided due to possible additive effects and hypotension.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertility

No mutagenic potential of haloperidol was found in the Ames Salmonella microsomal activation assay. Negative or inconsistent positive findings have been obtained in in vitro and in vivo studies of effects of haloperidol on chromosome structure and number. The available cytogenetic evidence is considered too inconsistent to be conclusive at this time.

Carcinogenicity studies using oral haloperidol were conducted in Wistar rats (dosed at up to 5 mg/kg daily for 24 months) and in Albino Swiss mice (dosed at up to 5 mg/kg daily for 18 months). In the rat study survival was less than optimal in all dose groups, reducing the number of rats at risk for developing tumors. However, although a relatively greater number of rats survived to the end of the study in high- dose male and female groups, these animals did not have a greater incidence of tumors than control animals. Therefore, although not optimal, this study does suggest the absence of a haloperidol related increase in the incidence of neoplasia in rats at doses up to 20 times the usual daily human dose for chronic or resistant patients.

In female mice at 5 and 20 times the highest initial daily dose for chronic or resistant patients, there was a statistically significant increase in mammary gland neoplasia and total tumor incidence; at 20 times the same daily dose there was a statistically significant increase in pituitary gland neoplasia. In male mice, no statistically significant differences in incidences of total tumors or specific tumor types were noted.

Antipsychotic drugs elevate prolactin levels; the elevation persists during chronic administration. Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if the prescription of these drugs is contemplated in a patient with a previously detected breast cancer. Although disturbances such as galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence have been reported, the clinical significance of elevated serum prolactin levels is unknown for most patients. An increase in mammary neoplasms has been found in rodents after chronic administration of antipsychotic drugs. Neither clinical studies nor epidemiologic studies conducted to date, however, have shown an association between chronic administration of these drugs and mammary tumorigenesis; the available evidence is considered too limited to be conclusive at this time.

There are no well controlled studies with haloperidol in pregnant women. There are reports, however, of cases of limb malformations observed following maternal use of haloperidol along with other drugs which have suspected teratogenic potential during the first trimester of pregnancy. Causal relationships were not established in these cases. Since such experience does not exclude the possibility of fetal damage due to haloperidol, this drug should be used during pregnancy or in women likely to become pregnant only if the benefit clearly justifies a potential risk to the fetus.

Nursing Mothers

Since haloperidol is excreted in human breast milk, infants should not be nursed during drug treatment with haloperidol.

Geriatric Use

Clinical studies of haloperidol did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not consistently identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. However, the prevalence of tardive dyskinesia appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women (see WARNINGS, Tardive Dyskinesia ). Also, the pharmacokinetics of haloperidol in geriatric patients generally warrants the use of lower doses (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions are discussed in more detail in other sections of the labeling:

- WARNINGS, Increased mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

- WARNINGS, Cardiovascular Effects

- WARNINGS, Tardive Dyskinesia

- WARNINGS, Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

- WARNINGS, Hypersensitivity Reactions

- WARNINGS, Falls

- WARNINGS, Usage in Pregnancy

- WARNINGS, Combined Use of Haloperidol and Lithium

- WARNINGS, General

- PRECAUTIONS, Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

- PRECAUTIONS, Withdrawal Emergent Dyskinesia

- PRECAUTIONS, Other

Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug, and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

The data described below reflect exposure to haloperidol in the following:

- 284 patients who participated in 3 double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials with haloperidol (oral formulation, 2 to 20 mg/day); two trials were in the treatment of schizophrenia and one in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

- 1295 patients who participated in 16 double-blind, active comparator-controlled clinical trials with haloperidol (injection or oral formulation, 1 to 45 mg/day) in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Based on the pooled safety data, the most common adverse reactions in haloperidol-treated patients from these double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials (≥5%) were: extrapyramidal disorder, hyperkinesia, tremor, hypertonia, dystonia, and somnolence.

Additional Adverse Reactions Reported in Double-Blind, Placebo- or Active Comparator-Controlled Clinical Trials with Injectable or Oral Haloperidol

Additional adverse reactions that are listed below were reported by haloperidol-treated patients in double-blind, active comparator-controlled clinical trials with the injectable or oral formulation, or at <1% incidence in double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled, clinical trials with the oral formulation.

Cardiac Disorders: Tachycardia

Endocrine Disorders: Hyperprolactinemia

Eye Disorders: Vision blurred

Investigations: Weight increased

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: Torticollis, Trismus, Muscle rigidity, Muscle twitching

Nervous System Disorders: Akathisia, Dizziness, Dyskinesia, Hypokinesia, Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, Nystagmus, Oculogyric crisis, Parkinsonism, Sedation, Tardive dyskinesia

Psychiatric Disorders: Loss of libido, Restlessness

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: Amenorrhea, Galactorrhea, Dysmenorrhea, Erectile dysfunction, Menorrhagia, Breast discomfort

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: Acneiform skin reactions

Vascular Disorders: Hypotension, Orthostatic hypotension

Adverse Reactions Reported at ≥1% Incidence in Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials with Oral Haloperidol

Adverse reactions occurring in ³1% of haloperidol-treated patients and at higher rate than placebo in 3 double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled, clinical trials with the oral formulation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Adverse Reactions Occurring in >1% of Haloperidol-Treated Patients in Double-Blind, Parallel Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials (Oral Haloperidol)

System/Organ Class

Adverse Reaction

Haloperidol

(n=284)

%

Placebo

(n=282)

%

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Constipation

4.2

1.8

Dry mouth

1.8

0.4

Salivary hypersecretion

1.2

0.7

Nervous System Disorders

Extrapyramidal disordera

50.7

16

Hyperkinesia

10.2

2.5

Tremor

8.1

3.6

Hypertonia

7.4

0.7

Dystonia

6.7

0.4

Bradykinesia

4.2

0.4

Somnolence

5.3

1.1

a Represents the total reporting rate for extrapyramidal disorder (reported term) and individual symptoms of extrapyramidal disorder, including events that did not meet the threshold of >1% for inclusion in this table.

Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions relating to the active moiety haloperidol have been identified during postapproval use of haloperidol or haloperidol decanoate. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: Pancytopenia, Agranulocytosis, Thrombocytopenia, Leukopenia, Neutropenia

Cardiac Disorders: Ventricular fibrillation, Torsade de pointes, Ventricular tachycardia, Extrasystoles

Endocrine Disorders: Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Gastrointestinal Disorders: Vomiting, Nausea

General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions: Sudden death, Face edema, Edema, Hyperthermia, Hypothermia

Hepatobiliary Disorders: Acute hepatic failure, Hepatitis, Cholestasis, Jaundice, Liver function test abnormal

Immune System Disorders: Anaphylactic reaction, Hypersensitivity Investigations: Electrocardiogram QT prolonged, Weight decreased

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders: Hypoglycemia

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: Rhabdomyolysis

Nervous System Disorders: Convulsion, Headache, Opisthotonus, Tardive dystonia

Pregnancy, Puerperium and Perinatal Conditions: Drug withdrawal syndrome neonatal

Psychiatric Disorders: Agitation, Confusional state, Depression, Insomnia

Renal and Urinary Disorders: Urinary retention

Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: Priapism, Gynecomastia

Respiratory, Thoracic and Mediastinal Disorders: Laryngeal edema, Bronchospasm, Laryngospasm, Dyspnea

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: Angioedema, Dermatitis exfoliative, Hypersensitivity vasculitis, Photosensitivity reaction, Urticaria, Pruritus, Rash, Hyperhidrosis

-

OVERDOSAGE

Manifestations

In general, the symptoms of overdosage would be an exaggeration of known pharmacologic effects and adverse reactions, the most prominent of which would be: 1) severe extrapyramidal reactions, 2) hypotension, or 3) sedation. The patient would appear comatose with respiratory depression and hypotension which could be severe enough to produce a shock-like state. The extrapyramidal reactions would be manifested by muscular weakness or rigidity and a generalized or localized tremor as demonstrated by the akinetic or agitans types respectively. With accidental overdosage, hypertension rather than hypotension occurred in a two-year old child. The risk of ECG changes associated with torsade de pointes should be considered. (For further information regarding torsade de pointes, please refer to ADVERSE REACTIONS.)

Treatment

Since there is no specific antidote, treatment is primarily supportive. A patent airway must be established by use of an oropharyngeal airway or endotracheal tube or, in prolonged cases of coma, by tracheostomy. Respiratory depression may be counteracted by artificial respiration and mechanical respirators. Hypotension and circulatory collapse may be counteracted by use of intravenous fluids, plasma, or concentrated albumin, and vasopressor agents such as metaraminol, phenylephrine and norepinephrine. Epinephrine should not be used. In case of severe extrapyramidal reactions, antiparkinson medication should be administered. ECG and vital signs should be monitored especially for signs of QT-prolongation or dysrhythmias and monitoring should continue until the ECG is normal. Severe arrhythmias should be treated with appropriate anti-arrhythmic measures.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

There is considerable variation from patient to patient in the amount of medication required for treatment. As with all drugs used to treat schizophrenia, dosage should be individualized according to the needs and response of each patient. Dosage adjustments, either upward or downward, should be carried out as rapidly as practicable to achieve optimum therapeutic control.

To determine the initial dosage, consideration should be given to the patient's age, severity of illness, previous response to other antipsychotic drugs, and any concomitant medication or disease state. Debilitated or geriatric patients, as well as those with a history of adverse reactions to antipsychotic drugs, may require less haloperidol. The optimal response in such patients is usually obtained with more gradual dosage adjustments and at lower dosage levels.

Parenteral medication, administered intramuscularIy in doses of 2 to 5 mg, is utilized for prompt control of the acutely agitated schizophrenic patient with moderately severe to very severe symptoms. Depending on the response of the patient, subsequent doses may be given, administered as often as every hour, although 4 to 8 hour intervals may be satisfactory. The maximum dose is 20 mg/day.

Controlled trials to establish the safety and effectiveness of intramuscular administration in children have not been conducted.

Parenteral drug products should be inspected visually for particulate matter and discoloration prior to administration, whenever solution and container permit.

Switchover Procedure

An oral form should supplant the injectable as soon as practicable. In the absence of bioavailability studies establishing bioequivalence between these two dosage forms the following guidelines for dosage are suggested. For an initial approximation of the total daily dose required, the parenteral dose administered in the preceding 24 hours may be used. Since this dose is only an initial estimate, it is recommended that careful monitoring of clinical signs and symptoms, including clinical efficacy, sedation, and adverse effects, be carried out periodically for the first several days following the initiation of switchover. In this way, dosage adjustments, either upward or downward, can be quickly accomplished. Depending on the patient's clinical status, the first oral dose should be given within 12 to 24 hours following the last parenteral dose.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Haloperidol Injection, USP, equivalent to 5 mg/mL haloperidol (as the lactate), is supplied as follows:

NDC: 0143-9319-25 - 1 mL Single-dose vial in carton of 25.

Store at 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Protect from light. Do not freeze.

Keep out of reach of children.

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corp. at 1-877-845-0689, or the FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

For Product Inquiry call 1-877-845-0689.

PREMIERProRx®

Manufactured by:

HIKMA FARMACÊUTICA (PORTUGAL), S.A.

Estrada do Rio da Mó, 8, 8A e 8B – Fervença – 2705-906 Terrugem SNT, PORTUGAL

Distributed by:

West-Ward Pharmaceuticals

Eatontown, NJ 07724 USA

PREMIERProRx® is a registered trademark of Premier Healthcare Alliance, L.P., used under license.

Revised May 2019

PIN493-PRE/2

-

VIAL LABEL

Haloperidol Injection, USP 5 mg/mL vial label Premier ProRx

NDC: 0143-9319-01 Rx only

Haloperidol Injection, USP

(For Immediate Release)

5 mg/mL

FOR INTRAMUSCULAR

USE ONLY

-

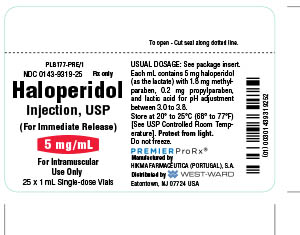

CARTON LABEL

Haloperidol Injection, USP 5 mg/mL Premier Label Carton

NDC: 0143-9319-25 Rx only

Haloperidol Injection, USP

(For Immediate Release)

5 mg/mL

FOR INTRAMUSCULAR

USE ONLY

25 x 1 mL Single-dose Vials

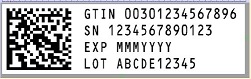

- SERIALIZATION IMAGE

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

HALOPERIDOL

haloperidol lactate injectionProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 0143-9319 Route of Administration INTRAMUSCULAR Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength HALOPERIDOL LACTATE (UNII: 6387S86PK3) (HALOPERIDOL - UNII:J6292F8L3D) HALOPERIDOL 5 mg in 1 mL Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength METHYLPARABEN (UNII: A2I8C7HI9T) 1.8 mg in 1 mL PROPYLPARABEN (UNII: Z8IX2SC1OH) 0.2 mg in 1 mL LACTIC ACID (UNII: 33X04XA5AT) Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 0143-9319-25 25 in 1 BOX 09/14/2018 1 1 mL in 1 VIAL; Type 0: Not a Combination Product Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA075858 09/14/2018 Labeler - Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. (001230762) Registrant - Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. (001230762)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.