Zonisamide by Proficient Rx LP ZONISAMIDE capsule

Zonisamide by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Zonisamide by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Proficient Rx LP. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

DESCRIPTION

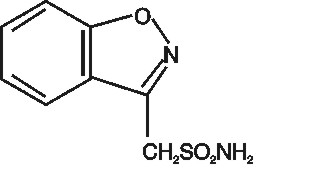

Zonisamide USP is an antiseizure drug chemically classified as a sulfonamide and unrelated to other antiseizure agents. The active ingredient is zonisamide USP, 1,2 benzisoxazole-3-methanesulfonamide. The empirical formula is C8H8N2O3S with a molecular weight of 212.23. Zonisamide USP is a white powder, pKa = 10.2, and is moderately soluble in water (0.80 mg/mL) and 0.1 N HCl (0.50 mg/mL).

The chemical structure is:

Zonisamide USP is supplied for oral administration as capsules containing 25 mg, 50 mg or 100 mg zonisamide USP. Each capsule contains the labeled amount of zonisamide USP plus the following inactive ingredients: microcrystalline cellulose, hydrogenated vegetable oil, and sodium lauryl sulfate. The printed capsule shell of the different strengths is made from the following ingredients:

25 mg – D&C Red #28, FD&C Blue #1, gelatin and titanium dioxide

50 mg – D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Red #40, gelatin and titanium dioxide

100 mg - D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Yellow #6, gelatin and titanium dioxide

The dyes used in the printing ink are FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Blue #2, FD&C Red #40, D&C Yellow #10 aluminium lake and iron oxide black. Additionally, the printing ink also contains n-butyl alcohol, ethanol, propylene glycol and shellac.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action:

The precise mechanism(s) by which zonisamide exerts its antiseizure effect is unknown. Zonisamide demonstrated anticonvulsant activity in several experimental models. In animals, zonisamide was effective against tonic extension seizures induced by maximal electroshock but ineffective against clonic seizures induced by subcutaneous pentylenetetrazol. Zonisamide raised the threshold for generalized seizures in the kindled rat model and reduced the duration of cortical focal seizures induced by electrical stimulation of the visual cortex in cats. Furthermore, zonisamide suppressed both interictal spikes and the secondarily generalized seizures produced by cortical application of tungstic acid gel in rats or by cortical freezing in cats. The relevance of these models to human epilepsy is unknown.

Zonisamide may produce these effects through action at sodium and calcium channels. In vitro pharmacological studies suggest that zonisamide blocks sodium channels and reduces voltage-dependent, transient inward currents (T-type Ca2+ currents), consequently stabilizing neuronal membranes and suppressing neuronal hypersynchronization. In vitro binding studies have demonstrated that zonisamide binds to the GABA/benzodiazepine receptor ionophore complex in an allosteric fashion which does not produce changes in chloride flux. Other in vitro studies have demonstrated that zonisamide (10 to 30 mcg/mL) suppresses synaptically-driven electrical activity without affecting postsynaptic GABA or glutamate responses (cultured mouse spinal cord neurons) or neuronal or glial uptake of [3H]-GABA (rat hippocampal slices). Thus, zonisamide does not appear to potentiate the synaptic activity of GABA. In vivo microdialysis studies demonstrated that zonisamide facilitates both dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. Zonisamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. The contribution of this pharmacological action to the therapeutic effects of zonisamide is unknown. However, as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, zonisamide may cause metabolic acidosis (see WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection).

Pharmacokinetics:

Absorption

Following a 200 to 400 mg oral zonisamide dose, peak plasma concentrations (range: 2 to 5 mcg/mL) in normal volunteers occur within 2 to 6 hours. In the presence of food, the time to maximum concentration is delayed, occurring at 4 to 6 hours, but food has no effect on the bioavailability of zonisamide. Zonisamide absorption is dose-proportional in the range of 200 to 400 mg. Cmax and AUC, however, increase disproportionately at 800 mg, possibly due to saturable binding of zonisamide to red blood cells. Once a stable dose is reached, steady state is achieved within 14 days.

Distribution

The apparent volume of distribution (V/F) of zonisamide is about 1.45 L/kg following a 400 mg oral dose. Zonisamide, at concentrations of 1 to 7 mcg/mL is approximately 40% bound to human plasma proteins. Zonisamide extensively binds to erythrocytes, resulting in an eight-fold higher concentration of zonisamide in red blood cells than in plasma. Protein binding of zonisamide is unaffected in the presence of therapeutic concentrations of phenytoin, phenobarbital or carbamazepine.

Metabolism and Elimination:

Following oral administration of 14C-zonisamide to healthy volunteers, only zonisamide was detected in plasma. Zonisamide is excreted primarily in urine as parent drug and as the glucuronide of a metabolite. Following multiple dosing, 62% of the radiolabeled dose was recovered in the urine, with 3% in the feces by day 10. Zonisamide undergoes acetylation by N-acetyl-transferases to form N-acetyl zonisamide and reduction to form the open ring metabolite, 2–sulfamoylacetyl phenol (SMAP). Of the excreted dose, 35% was recovered as zonisamide, 15% as N-acetyl zonisamide, and 50% as the glucuronide of SMAP. Reduction of zonisamide to SMAP is mediated by cytochrome P450 isozyme 3A4 (CYP3A4). Zonisamide does not induce its own metabolism. The plasma clearance of oral zonisamide is approximately 0.30 to 0.35 mL/min/kg in patients not receiving enzyme-inducing antiepilepsy drugs (AEDs). The clearance of zonisamide is increased to 0.5 mL/min/kg in patients concurrently on enzyme-inducing AEDs.

After a single-dose administration, renal clearance of zonisamide is approximately 3.5 mL/min. The clearance of an oral dose of zonisamide from red blood cells is 2 mL/min. The elimination half-life of zonisamide in plasma is approximately 63 hours. The elimination half-life of zonisamide in red blood cells is approximately 105 hours.

Specific Populations:

Renal Impairment: Single 300 mg zonisamide doses were administered to three groups of volunteers. Group 1 was a healthy group with a creatinine clearance ranging from 70 to 152 mL/min. Group 2 and Group 3 had creatinine clearances ranging from 14.5 to 59 mL/min and 10 to 20 mL/min, respectively. Zonisamide renal clearance decreased with decreasing renal function (3.42, 2.50, 2.23 mL/min, respectively). Marked renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 20 mL/min) was associated with an increase in zonisamide AUC of 35% (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION section).

Hepatic Impairment: The pharmacokinetics of zonisamide in patients with impaired liver function have not been studied (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION section).

Age: The pharmacokinetics of a 300 mg single dose of zonisamide was similar in young (mean age 28 years) and elderly subjects (mean age 69 years).

Gender and Race: Information on the effect of gender and race on the pharmacokinetics of zonisamide is not available.

Effects of zonisamide on cytochrome P450 enzymes

In vitro studies using human liver microsomes show insignificant (<25%) inhibition of cytochrome P450 isozymes 1A2, 2A6, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4, 2B6 or 2C8 at zonisamide levels approximately two-fold or greater than clinically relevant unbound serum concentrations. Therefore, zonisamide is not expected to affect the pharmacokinetics of other drugs via cytochrome P450-mediated mechanisms.

Potential for zonisamide to affect other drugs

Anti-epileptic drugs

In epileptic patients, steady-state dosing with zonisamide resulted in no clinically relevant pharmacokinetic effects on carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or sodium valproate.

Oral contraceptives

In healthy subjects, steady state dosing with zonisamide did not affect serum concentrations of ethinylestradiol or norethisterone in a combined oral contraceptive.

CYP2D6 substrates:

Coadministration of multiple dosing of zonisamide up to 400 mg/day with single 50 mg doses of desipramine did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetic parameters of desipramine, a probe drug for CYP2D6 activity.

P-gp substrate

An in vitro study showed that zonisamide is a weak inhibitor of P-gp (MDR1) with an IC50 of 267 μmol/L. There is a theoretical potential for zonisamide to affect the pharmacokinetics of drugs which are P-gp substrates.

Caution is advised when starting or stopping zonisamide or changing the zonisamide dose in patients who are also receiving drugs which are P-gp substrates (e.g., digoxin, quinidine)

Potential for Medicinal Product to Affect Zonisamide

Concomitant medications that can induce or inhibit CYP3A4 or N-acetyl-transferases may affect the pharmacokinetics of zonisamide. Drugs which inhibit or induce glucuronide conjugation are not expected to influence the pharmacokinetics of zonisamide.

The absence of a clinically significant pharmacokinetic interaction between zonisamide and lamotrigine indicates a low potential for zonisamide to interact with substances which are metabolized by UDP-GT.

CYP3A4 Induction: Drugs that induce liver enzymes increase the metabolism and clearance of zonisamide and decrease its half-life. The half-life of zonisamide following a 400 mg dose in patients concurrently on enzyme-inducing AEDs such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobarbital was between 27 to 38 hours; the half-life of zonisamide in patients concurrently on the non-enzyme inducing AED, valproate, was 46 hours.

These effects are unlikely to be of clinical significance when zonisamide is added to existing therapy; however, changes in zonisamide concentrations may occur if concomitant CYP3A4 inducing anti-epileptic or other drugs are withdrawn, dose adjusted or introduced, an adjustment of the zonisamide dose may be required. If coadministration with a potent CYP3A4 inducer (e.g., rifampicin) is necessary, the patient should be closely monitored and the dose of zonisamide and other drugs that are CYP3A4 substrate may need to be adjusted.

CYP3A4 Inhibition: Steady-state dosing of either ketoconazole (400 mg/day) or cimetidine (1200 mg/day) had no clinically relevant effects on the single dose pharmacokinetics of zonisamide given to healthy subjects. Therefore, modification of zonisamide dosing is not necessary when co-administered with known CYP3A4 inhibitors.

Interactions of Zonisamide with Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors:

Concomitant use of zonisamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, with any other carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (e.g., topiramate, acetazolamide or dichlorphenamide), may increase the severity of metabolic acidosis and may also increase the risk of kidney stone formation. Therefore, if zonisamide is given concomitantly with another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, the patient should be monitored for the appearance or worsening of metabolic acidosis (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions subsection).

Clinical Studies:

The effectiveness of zonisamide as adjunctive therapy (added to other antiepilepsy drugs) has been established in three multicenter, placebo-controlled, double blind, 3-month clinical trials (two domestic, one European) in 499 patients with refractory partial onset seizures with or without secondary generalization. Each patient had a history of at least four partial onset seizures per month in spite of receiving one or two antiepilepsy drugs at therapeutic concentrations. The 499 patients (209 women, 290 men) ranged in age from 13–68 years with a mean age of about 35 years. In the two US studies, over 80% of patients were Caucasian; 100% of patients in the European study were Caucasian.

Zonisamide or placebo was added to the existing therapy. The primary measure of effectiveness was median percent reduction from baseline in partial seizure frequency. The secondary measure was proportion of patients achieving a 50% or greater seizure reduction from baseline (responders). The results described below are for all partial seizures in the intent-to-treat populations.

In the first study (n = 203), all patients had a 1-month baseline observation period, then received placebo or zonisamide in one of two dose escalation regimens; either 1) 100 mg/day for five weeks, 200 mg/day for one week, 300 mg/day for one week, and then 400 mg/day for five weeks; or 2) 100 mg/day for one week, followed by 200 mg/day for five weeks, then 300 mg/day for one week, then 400 mg/day for five weeks. This design allowed a 100 mg vs. placebo comparison over weeks 1–5, and a 200 mg vs. placebo comparison over weeks 2–6; the primary comparison was 400 mg (both escalation groups combined) vs. placebo over weeks 8–12. The total daily dose was given as twice a day dosing. Statistically significant treatment differences favoring zonisamide were seen for doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/day.

In the second (n = 152) and third (n = 138) studies, patients had a 2–3 month baseline, then were randomly assigned to placebo or zonisamide for three months. Zonisamide was introduced by administering 100 mg/day for the first week, 200 mg/day the second week, then 400 mg/day for two weeks, after which the dose (zonisamide or placebo) could be adjusted as necessary to a maximum dose of 20 mg/kg/day or a maximum plasma level of 40 mcg/mL. In the second study, the total daily dose was given as twice a day dosing; in the third study, it was given as a single daily dose. The average final maintenance doses received in the studies were 530 and 430 mg/day in the second and third studies, respectively. Both studies demonstrated statistically significant differences favoring zonisamide for doses of 400 to 600 mg/day, and there was no apparent difference between once daily and twice daily dosing (in different studies). Analysis of the data (first 4 weeks) during titration demonstrated statistically significant differences favoring zonisamide at doses between 100 and 400 mg/day. The primary comparison in both trials was for any dose over Weeks 5 – 12.

Table 1. Median % Reduction in All Partial Seizures and % Responders in Primary Efficacy Analyses: Intent-To-Treat Analysis Study

Median % reduction in partial seizures

% Responders

Zonisamide

Placebo

Zonisamide

Placebo

Study 1:

n=98

n=72

n=98

n=72

Weeks 8-12:

40.5%

9%

41.8%

22.2%

Study 2:

n=69

n=72

n=69

n=72

Weeks 5-12:

29.6%

-3.2%

29%

15%

Study 3:

n=67

n=66

n=67

n=66

Weeks 5-12:

27.2%1

-1.1%

28%

12%

Table 2. Median % Reduction in All Partial Seizures and % Responders for Dose Analyses in Study 1: Intent-To-Treat Analysis Dose Group

Median % reduction in partial seizures

% Responders

Zonisamide

Placebo

Zonisamide

Placebo

100-400 mg/day:

n=112

n=83

n=112

n=83

Weeks 1-12:

32.3%

5.6%

32.1%

9.6%

100 mg/day:

n=56

n=80

n=56

n=80

Weeks 1-5:

24.7%

8.3%

25%

11.3%

200 mg/day:

n=55

n=82

n=55

n=82

Weeks 2-6:

20.4%

4%

25.5%

9.8%

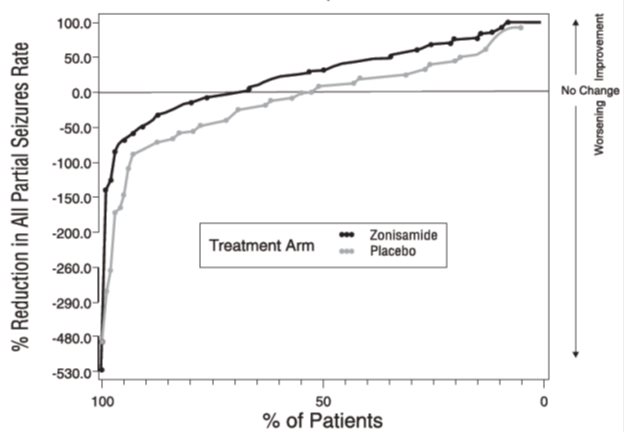

Figure 1 presents the proportion of patients (X-axis) whose percentage reduction from baseline in the all partial seizure rate was at least as great as that indicated on the Y-axis in the second and third placebo-controlled trials. A positive value on the Y-axis indicates an improvement from baseline (i.e., a decrease in seizure rate), while a negative value indicates a worsening from baseline (i.e., an increase in seizure rate). Thus, in a display of this type, the curve for an effective treatment is shifted to the left of the curve for placebo. The proportion of patients achieving any particular level of reduction in seizure rate was consistently higher for the zonisamide groups compared to the placebo groups. For example, Figure 1 indicates that approximately 27% of patients treated with zonisamide experienced a 75% or greater reduction, compared to approximately 12% in the placebo groups.

Figure 1: Proportion of Patients Achieving Differing Levels of Seizure Reduction in Zonisamide and Placebo Groups in Studies 2 and 3

No differences in efficacy based on age, sex or race, as measured by a change in seizure frequency from baseline, were detected.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

Potentially Fatal Reactions to Sulfonamides: Fatalities have occurred, although rarely, as a result of severe reactions to sulfonamides (zonisamide is a sulfonamide) including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, fulminant hepatic necrosis, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and other blood dyscrasias. Such reactions may occur when a sulfonamide is readministered irrespective of the route of administration. If signs of hypersensitivity or other serious reactions occur, discontinue zonisamide immediately. Specific experience with sulfonamide-type adverse reaction to zonisamide is described below.

Serious Skin Reactions: Consideration should be given to discontinuing zonisamide in patients who develop an otherwise unexplained rash. If the drug is not discontinued, patients should be observed frequently. Seven deaths from severe rash [i.e. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)] were reported in the first 11 years of marketing in Japan. All of the patients were receiving other drugs in addition to zonisamide. In post-marketing experience from Japan, a total of 49 cases of SJS or TEN have been reported, a reporting rate of 46 per million patient-years of exposure. Although this rate is greater than background, it is probably an underestimate of the true incidence because of under-reporting. There were no confirmed cases of SJS or TEN in the US, European, or Japanese development programs.

In the US and European randomized controlled trials, 6 of 269 (2.2%) zonisamide patients discontinued treatment because of rash compared to none on placebo. Across all trials during the US and European development, rash that led to discontinuation of zonisamide was reported in 1.4% of patients (12 events per 1000 patient-years of exposure). During Japanese development, serious rash or rash that led to study drug discontinuation was reported in 2% of patients (27.8 events per 1000 patient years). Rash usually occurred early in treatment, with 85% reported within 16 weeks in the US and European studies and 90% reported within two weeks in the Japanese studies. There was no apparent relationship of dose to the occurrence of rash.

Serious Hematologic Events:

Two confirmed cases of aplastic anemia and one confirmed case of agranulocytosis were reported in the first 11 years of marketing in Japan, rates greater than generally accepted background rates. There were no cases of aplastic anemia and two confirmed cases of agranulocytosis in the US, European, or Japanese development programs. There is inadequate information to assess the relationship, if any, between dose and duration of treatment and these events.

Oligohidrosis and Hyperthermia in Pediatric Patients:

Oligohidrosis, sometimes resulting in heat stroke and hospitalization, is seen in association with zonisamide in pediatric patients.

During the pre-approval development program in Japan, one case of oligohidrosis was reported in 403 pediatric patients, an incidence of 1 case per 285 patient-years of exposure. While there were no cases reported in the US or European development programs, fewer than 100 pediatric patients participated in these trials.

In the first 11 years of marketing in Japan, 38 cases were reported, an estimated reporting rate of about 1 case per 10,000 patient-years of exposure. In the first year of marketing in the US, 2 cases were reported, an estimated reporting rate of about 12 cases per 10,000 patient-years of exposure. These rates are underestimates of the true incidence because of under-reporting. There has also been one report of heat stroke in an 18-year-old patient in the US.

Decreased sweating and an elevation in body temperature above normal characterized these cases. Many cases were reported after exposure to elevated environmental temperatures. Heat stroke, requiring hospitalization, was diagnosed in some cases. There have been no reported deaths.

Pediatric patients appear to be at an increased risk for zonisamide-associated oligohidrosis and hyperthermia. Patients, especially pediatric patients, treated with zonisamide should be monitored closely for evidence of decreased sweating and increased body temperature, especially in warm or hot weather. Caution should be used when zonisamide is prescribed with other drugs that predispose patients to heat-related disorders; these drugs include, but are not limited to, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and drugs with anticholinergic activity.

The practitioner should be aware that the safety and effectiveness of zonisamide in pediatric patients have not been established, and that zonisamide is not approved for use in pediatric patients.

Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including zonisamide, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled, clinical trials (mono- and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5-100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed.

Table 3 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 3: Risk by indication for antiepileptic drugs in the pooled analysis Indication

Placebo Patients with Events per 1000 Patients

Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients

Relative Risk: Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients

Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events per 1000 Patients

Epilepsy

1

3.4

3.5

2.4

Psychiatric

5.7

8.5

1.5

2.9

Other

1

1.8

1.9

0.9

Total

2.4

4.3

1.8

1.9

The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing zonisamide or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers (see WARNINGS, Cognitive/ Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events subsection below).

Metabolic Acidosis:

Zonisamide causes hyperchloremic, non-anion gap, metabolic acidosis (i.e., decreased serum bicarbonate below the normal reference range in the absence of chronic respiratory alkalosis) (see PRECAUTIONS, Laboratory Tests subsection). This metabolic acidosis is caused by renal bicarbonate loss due to the inhibitory effect of zonisamide on carbonic anhydrase.

Generally, zonisamide-induced metabolic acidosis occurs early in treatment, but it can develop at any time during treatment. Metabolic acidosis generally appears to be dose-dependent and can occur at doses as low as 25 mg daily.

Conditions or therapies that predispose to acidosis (such as renal disease, severe respiratory disorders, status epilepticus, diarrhea, ketogenic diet, or specific drugs) may be additive to the bicarbonate lowering effects of zonisamide.

Some manifestations of acute or chronic metabolic acidosis include hyperventilation, nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia, or more severe sequelae including cardiac arrhythmias or stupor. Chronic, untreated, metabolic acidosis may increase the risk for nephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis. Nephrolithiasis has been observed in the clinical development program in 4% of adults treated with zonisamide, has also been detected by renal ultrasound in 8% of pediatric treated patients who had at least one ultrasound prospectively collected, and was reported as an adverse event in 3% (4/133) of pediatric patients (see PRECAUTIONS, Kidney Stones subsection).

Chronic, untreated metabolic acidosis may result in osteomalacia (referred to as rickets in pediatric patients) and/or osteoporosis with an increased risk for fracture. Of potential relevance, zonisamide treatment was associated with reductions in serum phosphorus and increases in serum alkaline phosphatase, changes that may be related to metabolic acidosis and osteomalacia (see PRECAUTIONS, Laboratory Tests subsection).

Chronic, untreated metabolic acidosis in pediatric patients may reduce growth rates. A reduction in growth rate may eventually decrease the maximal height achieved. The effect of zonisamide on growth and bone-related sequelae has not been systematically investigated.

Measurement of baseline and periodic serum bicarbonate during treatment is recommended. If metabolic acidosis develops and persists, consideration should be given to reducing the dose or discontinuing zonisamide (using dose tapering). If the decision is made to continue patients on zonisamide in the face of persistent acidosis, alkali treatment should be considered.

Serum bicarbonate was not measured in the adjunctive controlled trials of adults with epilepsy. However, serum bicarbonate was studied in three clinical trials for indications which have not been approved: a placebo-controlled trial for migraine prophylaxis in adults, a controlled trial for monotherapy in epilepsy in adults, and an open label trial for adjunctive treatment of epilepsy in pediatric patients (3-16 years). In adults, mean serum bicarbonate reductions ranged from approximately 2 mEq/L at daily doses of 100 mg to nearly 4mEq at daily doses of 300 mg. In pediatric patients, mean serum bicarbonate reductions ranged from approximately 2 mEq/L at daily doses from above 100mg up to 300 mg, to nearly 4 mEq/L at daily doses from above 400 mg up to 600 mg.

In two controlled studies in adults, the incidence of a persistent treatment-emergent decrease in serum bicarbonate to less than 20 mEq/L (observed at 2 or more consecutive visits or the final visit) was dose-related at relatively low zonisamide doses. In the monotherapy trial of epilepsy, the incidence of a persistent treatment-emergent decrease in serum bicarbonate was 21% for daily zonisamide doses of 25 mg or 100 mg, and was 43% at a daily dose of 300 mg. In a placebo-controlled trial for prophylaxis of migraine, the incidence of a persistent treatment-emergent decrease in serum bicarbonate was 7% for placebo, 29% for 150 mg daily, and 34% for 300 mg daily. The incidence of persistent markedly abnormally low serum bicarbonate (decrease to less than 17 mEq/L and more than 5 mEq/L from a pretreatment value of at least 20 mEq/L in these controlled trials was 2% or less.

In the pediatric study, the incidence of persistent, treatment-emergent decreases in serum bicarbonate to levels less than 20 mEq/L was 52%at doses up to 100 mg daily, was 90% for a wide range of doses up to 600 mg daily, and generally appeared to increase with higher doses. The incidence of a persistent markedly abnormally low serum bicarbonate value was 4% at doses up to 100 mg daily, was 18% for a wide range of doses up to 600 mg daily, and generally appeared to increase with higher doses. Some patients experienced moderately severe serum bicarbonate decrements down to a level as low as 10 mEq/L.

The relatively high frequencies of varying severities of metabolic acidosis observed in this study of pediatric patients (compared to the frequency and severity observed in various clinical trial development programs in adults) suggest that pediatric patients may be more likely to develop metabolic acidosis than adults.

Seizures on Withdrawal:

As with other AEDs, abrupt withdrawal of zonisamide in patients with epilepsy may precipitate increased seizure frequency or status epilepticus. Dose reduction or discontinuation of zonisamide should be done gradually.

Teratogenicity:

Women of child bearing potential who are given zonisamide should be advised to use effective contraception. Zonisamide was teratogenic in mice, rats, and dogs and embryolethal in monkeys when administered during the period of organogenesis. A variety of fetal abnormalities, including cardiovascular defects, and embryo-fetal deaths occurred at maternal plasma levels similar to or lower than therapeutic levels in humans. These findings suggest that the use of zonisamide during pregnancy in humans may present a significant risk to the fetus (see PRECAUTIONS, Pregnancy subsection).

Zonisamide should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Cognitive/ Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events:

Use of zonisamide was frequently associated with central nervous system-related adverse events. The most significant of these can be classified into three general categories: 1) psychiatric symptoms, including depression and psychosis, 2) psychomotor slowing, difficulty with concentration, and speech or language problems, in particular, word-finding difficulties, and 3) somnolence or fatigue.

In placebo-controlled trials, 2.2% of patients discontinued zonisamide or were hospitalized for depression compared to 0.4% of placebo patients. Among all epilepsy patients treated with zonisamide, 1.4% were discontinued and 1% were hospitalized because of reported depression or suicide attempts. In placebo-controlled trials, 2.2% of patients discontinued zonisamide or were hospitalized due to psychosis or psychosis-related symptoms compared to none of the placebo patients. Among all epilepsy patients treated with zonisamide, 0.9% were discontinued and 1.4% were hospitalized because of reported psychosis or related symptoms.

Psychomotor slowing and difficulty with concentration occurred in the first month of treatment and were associated with doses above 300 mg/day. Speech and language problems tended to occur after 6–10 weeks of treatment and at doses above 300 mg/day. Although in most cases these events were of mild to moderate severity, they at times led to withdrawal from treatment.

Somnolence and fatigue were frequently reported CNS adverse events during clinical trials with zonisamide. Although in most cases these events were of mild to moderate severity, they led to withdrawal from treatment in 0.2% of the patients enrolled in controlled trials. Somnolence and fatigue tended to occur within the first month of treatment. Somnolence and fatigue occurred most frequently at doses of 300–500 mg/day. Patients should be cautioned about this possibility and special care should be taken by patients if they drive, operate machinery, or perform any hazardous task.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Somnolence is commonly reported, especially at higher doses of zonisamide (see WARNINGS: Cognitive/ Neuropsychiatric Adverse Eventssubsection). Zonisamide is metabolized by the liver and eliminated by the kidneys; caution should therefore be exercised when administering zonisamide to patients with hepatic and renal dysfunction (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populations subsection).

Kidney Stones:

Among 991 patients treated during the development of zonisamide, 40 patients (4%) with epilepsy receiving zonisamide developed clinically possible or confirmed kidney stones (e.g. clinical symptomatology, sonography, etc.), a rate of 34 per 1000 patient-years of exposure (40 patients with 1168 years of exposure). Of these, 12 were symptomatic, and 28 were described as possible kidney stones based on sonographic detection. In nine patients, the diagnosis was confirmed by a passage of a stone or by a definitive sonographic finding. The rate of occurrence of kidney stones was 28.7 per 1000 patient-years of exposure in the first six months, 62.6 per 1000 patient-years of exposure between 6 and 12 months, and 24.3 per 1000 patient-years of exposure after 12 months of use. There are no normative sonographic data available for either the general population or patients with epilepsy.

Although the clinical significance of the sonographic findings may not be certain, the development of nephrolithiasis may be related to metabolic acidosis (see WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection). The analyzed stones were composed of calcium or urate salts. In general, increasing fluid intake and urine output can help reduce the risk of stone formation, particularly in those with predisposing risk factors. It is unknown, however, whether these measures will reduce the risk of stone formation in patients treated with zonisamide.

Although not approved in pediatric patients, sonographic findings consistent with nephrolithiasis were also detected in 8% of a subset of zonisamide treated pediatric patients who had at least one renal ultrasound prospectively performed in a clinical development program investigating open-label treatment. The incidence of kidney stone as an adverse event was 3% (see WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection).

Effect on Renal Function:

In several clinical studies, zonisamide was associated with a statistically significant 8% mean increase from baseline of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) compared to essentially no change in the placebo patients. The increase appeared to persist over time but was not progressive; this has been interpreted as an effect on glomerular filtration rate (GFR). There were no episodes of unexplained acute renal failure in clinical development in the US, Europe, or Japan. The decrease in GFR appeared within the first 4 weeks of treatment. In a 30-day study, the GFR returned to baseline within 2–3 weeks of drug discontinuation. There is no information about reversibility, after drug discontinuation, of the effects on GFR after long-term use. Zonisamide should be discontinued in patients who develop acute renal failure or a clinically significant sustained increase in the creatinine/BUN concentration. Zonisamide should not be used in patients with renal failure (estimated GFR < 50 mL/min) as there has been insufficient experience concerning drug dosing and toxicity.

Sudden Unexplained Death in Epilepsy:

During the development of zonisamide, nine sudden unexplained deaths occurred among 991 patients with epilepsy receiving zonisamide for whom accurate exposure data are available. This represents an incidence of 7.7 deaths per 1000 patient years. Although this rate exceeds that expected in a healthy population, it is within the range of estimates for the incidence of sudden unexplained deaths in patients with refractory epilepsy not receiving zonisamide (ranging from 0.5 per 1000 patient-years for the general population of patients with epilepsy, to 2–5 per 1000 patient-years for patients with refractory epilepsy; higher incidences range from 9–15 per 1000 patient-years among surgical candidates and surgical failures). Some of the deaths could represent seizure-related deaths in which the seizure was not observed.

Status Epilepticus:

Estimates of the incidence of treatment emergent status epilepticus in zonisamide-treated patients are difficult because a standard definition was not employed. Nonetheless, in controlled trials, 1.1% of patients treated with zonisamide had an event labeled as status epilepticus compared to none of the patients treated with placebo. Among patients treated with zonisamide across all epilepsy studies (controlled and uncontrolled), 1% of patients had an event reported as status epilepticus.

Information for Patients

Patients should be informed of the availability of a Medication Guide, and they should be instructed to read the Medication Guide prior to taking zonisamide. Patients should be instructed to take zonisamide only as prescribed.

Patients should be advised as follows: (See Medication Guide)

- Zonisamide may produce drowsiness, especially at higher doses. Patients should be advised not to drive a car or operate other complex machinery until they have gained experience on zonisamide sufficient to determine whether it affects their performance. Because of the potential of zonisamide to cause CNS depression, as well as other cognitive and/or neuropsychiatric adverse events, zonisamide should be used with caution if used in combination with alcohol or other CNS depressants.

- Patients should contact their physician immediately if a skin rash develops or seizures worsen.

- Patients should contact their physician immediately if they develop signs or symptoms, such as sudden back pain, abdominal pain, and/or blood in the urine, that could indicate a kidney stone. Increasing fluid intake and urine output may reduce the risk of stone formation, particularly in those with predisposing risk factors for stones.

- Patients should contact their physician immediately if a child has been taking zonisamide and is not sweating as usual with or without a fever.

- Because zonisamide can cause hematological complications, patients should contact their physician immediately if they develop a fever, sore throat, oral ulcers, or easy bruising.

- Suicidal Thinking and Behavior – Patients, their caregivers, and families should be counseled that AEDs, including zonisamide, may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

- Patients should contact their physician immediately if they develop fast breathing, fatigue/tiredness, loss of appetite, or irregular heart beat or palpitations (possible manifestations of metabolic acidosis).

-

As with other AEDs, patients should contact their physician if they intend to become pregnant or are pregnant during zonisamide therapy. Patients should notify their physician if they intend to breast-feed or are breast-feeding an infant.

Patients should be encouraged to enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry if they become pregnant. This registry is collecting information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. To enroll, patients can call the toll free number 1-888-233-2334 (see PRECAUTIONS, Pregnancy subsection).

Laboratory Tests

In several clinical studies, zonisamide was associated with a mean increase in the concentration of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of approximately 8% over the baseline measurement. Consideration should be given to monitoring renal function periodically (see PRECAUTIONS, Effect on Renal Functionsubsection).

Zonisamide increases serum chloride and alkaline phosphatase and decreases serum bicarbonate (see WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection), phosphorus, calcium, and albumin.

Drug Interactions with CNS depressants: Concomitant administration of zonisamide and alcohol or other CNS depressant drugs has not been evaluated in clinical studies. Because of the potential of zonisamide to cause CNS depression, as well as other cognitive and/or neuropsychiatric adverse events, zonisamide should be used with caution if used in combination with alcohol or other CNS depressants.

Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: Concomitant use of zonisamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, with any other carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (e.g., topiramate, acetazolamide or dichlorphenamide), may increase the severity of metabolic acidosis and may also increase the risk of kidney stone formation. Therefore, if zonisamide is given concomitantly with another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, the patient should be monitored for the appearance or worsening of metabolic acidosis (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Interactions of Zonisamide with Other Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors subsection).

Carcinogenicity, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

No evidence of carcinogenicity was found in mice or rats following dietary administration of zonisamide for two years at doses of up to 80 mg/kg/day. In mice, this dose is approximately equivalent to the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 400 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis. In rats, this dose is 1– 2 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

Zonisamide was mutagenic in an in vitro chromosomal aberration assay in CHL cells. Zonisamide was not mutagenic or clastogenic in other in vitro assays (Ames, mouse lymphoma tk assay, chromosomal aberration in human lymphocytes) or in the in vivo rat bone marrow cytogenetics assay.

Rats treated with zonisamide (20, 60, or 200 mg/kg) before mating and during the initial gestation phase showed signs of reproductive toxicity (decreased corpora lutea, implantations, and live fetuses) at all doses. The low dose in this study is approximately 0.5 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) on a mg/m2 basis.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C (see WARNINGS, Teratogenicity subsection):

Zonisamide may cause serious adverse fetal effects, based on clinical and nonclinical data. Zonisamide was teratogenic in multiple animal species.

Zonisamide treatment causes metabolic acidosis in humans. The effect of zonisamide-induced metabolic acidosis has not been studied in pregnancy; however, metabolic acidosis in pregnancy (due to other causes) may be associated with decreased fetal growth, decreased fetal oxygenation, and fetal death, and may affect the fetus’ ability to tolerate labor. Pregnant patients should be monitored for metabolic acidosis and treated as in the non-pregnant state. (See WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection).

Newborns of mothers treated with zonisamide should be monitored for metabolic acidosis because of transfer of zonisamide to the fetus and possible occurrence of transient metabolic acidosis following birth. Transient metabolic acidosis has been reported in neonates born to mothers treated during pregnancy with a different carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.

Zonisamide was teratogenic in mice, rats, and dogs and embryolethal in monkeys when administered during the period of organogenesis. Fetal abnormalities or embryo-fetal deaths occurred in these species at zonisamide dosage and maternal plasma levels similar to or lower than therapeutic levels in humans, indicating that use of this drug in pregnancy entails a significant risk to the fetus. A variety of external, visceral, and skeletal malformations was produced in animals by prenatal exposure to zonisamide. Cardiovascular defects were prominent in both rats and dogs.

Following administration of zonisamide (10, 30, or 60 mg/kg/day) to pregnant dogs during organogenesis, increased incidences of fetal cardiovascular malformations (ventricular septal defects, cardiomegaly, various valvular and arterial anomalies) were found at doses of 30 mg/kg/day or greater. The low effect dose for malformations produced peak maternal plasma zonisamide levels (25 mcg/mL) about 0.5 times the highest plasma levels measured in patients receiving the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 400 mg/day. In dogs, cardiovascular malformations were found in approximately 50% of all fetuses exposed to the high dose, which was associated with maternal plasma levels (44 mcg/mL) approximately equal to the highest levels measured in humans receiving the MRHD. Incidences of skeletal malformations were also increased at the high dose, and fetal growth retardation and increased frequencies of skeletal variations were seen at all doses in this study. The low dose produced maternal plasma levels (12 mcg/mL) about 0.25 times the highest human levels.

In cynomolgus monkeys, administration of zonisamide (10 or 20 mg/kg/day) to pregnant animals during organogenesis resulted in embryo-fetal deaths at both doses. The possibility that these deaths were due to malformations cannot be ruled out. The lowest embryolethal dose in monkeys was associated with peak maternal plasma zonisamide levels (5 mcg/mL) approximately 0.1 times the highest levels measured in patients at the MRHD.

In a mouse embryo-fetal development study, treatment of pregnant animals with zonisamide (125, 250, or 500 mg/kg/day) during the period of organogenesis resulted in increased incidences of fetal malformations (skeletal and/or craniofacial defects) at all doses tested. The low dose in this study is approximately 1.5 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. In rats, increased frequencies of malformations (cardiovascular defects) and variations (persistent cords of thymic tissue, decreased skeletal ossification) were observed among the offspring of dams treated with zonisamide (20, 60, or 200 mg/kg/day) throughout organogenesis at all doses. The low effect dose is approximately 0.5 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

Perinatal death was increased among the offspring of rats treated with zonisamide (10, 30, or 60 mg/kg/day) from the latter part of gestation up to weaning at the high dose, or approximately 1.4 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis. The no effect level of 30 mg/kg/day is approximately 0.7 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Zonisamide should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

To provide information regarding the effects of in utero exposure to zonisamide, physicians are advised to recommend that pregnant patients taking zonisamide enroll in the NAAED Pregnancy Registry. This can be done by calling the toll free number 1-888-233-2334, and must be done by patients themselves. Information on the registry can also be found at the website http://www.aedpregnancyregistry.org/.

Use in Nursing Mothers

Zonisamide is excreted in human milk. Because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants from zonisamide, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of zonisamide in children under age 16 have not been established. Cases of oligohidrosis and hyperpyrexia have been reported (see WARNINGS, Oligohidrosis and Hyperthermia in Pediatric Patients subsection). Zonisamide commonly causes metabolic acidosis in pediatric patients (see WARNINGS, Metabolic Acidosis subsection). Chronic untreated metabolic acidosis in pediatric patients may cause nephrolithiasis and/or nephrocalcinosis, osteoporosis and/or osteomalacia (potentially resulting in rickets), and may reduce growth rates. A reduction in growth rate may eventually decrease the maximal height achieved. The effect of zonisamide on growth and bone-related sequelae has not been systematically investigated.

Geriatric Use

Single dose pharmacokinetic parameters are similar in elderly and young healthy volunteers (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populationssubsection). Clinical studies of zonisamide did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common adverse reactions with zonisamide (an incidence at least 4% greater than placebo) in controlled clinical trials and shown in descending order of frequency were somnolence, anorexia, dizziness, ataxia, agitation/irritability, and difficulty with memory and/or concentration.

In controlled clinical trials, 12% of patients receiving zonisamide as adjunctive therapy discontinued due to an adverse reaction compared to 6% receiving placebo. Approximately 21% of the 1,336 patients with epilepsy who received zonisamide in clinical studies discontinued treatment because of an adverse reaction. The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence, fatigue and/or ataxia (6%), anorexia (3%), difficulty concentrating (2%), difficulty with memory, mental slowing, nausea/vomiting (2%), and weight loss (1%). Many of these adverse reactions were dose-related (see WARNINGSand PRECAUTIONS).

Adverse Reaction Incidence in Controlled Clinical Trials: Table 4 lists adverse reactions that occurred in at least 2% of patients treated with zonisamide in controlled clinical trials that were numerically more common in the zonisamide group. In these studies, either zonisamide or placebo was added to the patient’s current AED therapy.

Table 4. Adverse Reactions in Placebo-Controlled, Add-On Trials (Events that occurred in at least 2% of zonisamide-treated patients and occurred more frequently in zonisamide-treated than placebo-treated patients)

BODY SYSTEM/PREFERRED TERM

ZONISAMIDE

(n=269)

%

PLACEBO (n=230)

%

BODY AS A WHOLE

Headache

10

8

Abdominal Pain

6

3

Flu Syndrome

4

3

DIGESTIVE

Anorexia

13

6

Nausea

9

6

Diarrhea

5

2

Dyspepsia

3

1

Constipation

2

1

Dry Mouth

2

1

HEMATOLOGIC AND LYMPHATIC

Ecchymosis

2

1

METABOLIC AND NUTRITIONAL

Weight Loss

3

2

NERVOUS SYSTEM

Dizziness

13

7

Ataxia

6

1

Nystagmus

4

2

Paresthesia

4

1

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION-ALTERED COGNITIVE FUNCTION

Confusion

6

3

Difficulty Concentrating

6

2

Difficulty with Memory

6

2

Mental Slowing

4

2

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION-BEHAVIORAL ABNORMALITIES (NON-PSYCHOSIS-RELATED)

Agitation/Irritability

9

4

Depression

6

3

Insomnia

6

3

Anxiety

3

2

Nervousness

2

1

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION-BEHAVIORAL ABNORMALITIES (PSYCHOSIS-RELATED)

Schizophrenic/Schizophreniform Behavior

2

0

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION-CNS DEPRESSION

Somnolence

17

7

Fatigue

8

6

Tiredness

7

5

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION-SPEECH AND LANGUAGE ABNORMALITIES

Speech Abnormalities

5

2

Difficulties in Verbal Expression

2

<1

RESPIRATORY

Rhinitis

2

1

SKIN AND APPENDAGES

Rash

3

2

SPECIAL SENSES

Diplopia

6

3

Taste Perversion

2

0

Other Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials:

Zonisamide has been administered to 1,598 individuals during all clinical trials, only some of which were placebo-controlled. The frequencies represent the proportion of the 1,598 individuals exposed to zonisamide who experienced an event on at least one occasion. All events are included except those already listed in the previous table or discussed in WARNINGS or PRECAUTIONS, trivial events, those too general to be informative, and those not reasonably associated with zonisamide.

Events are further classified within each category and listed in order of decreasing frequency as follows: frequent occurring in at least 1:100 patient; infrequent occurring in 1:100 to 1:1000 patients; rare occurring in fewer than 1:1000 patients.

Body as a Whole:Frequent: Accidental injury, asthenia. Infrequent: Chest pain, flank pain, malaise, allergic reaction, face edema, neck rigidity. Rare: Lupus erythematosus.

Cardiovascular:Infrequent: Palpitation, tachycardia, vascular insufficiency, hypotension, hypertension, thrombophlebitis, syncope, bradycardia. Rare: Atrial fibrillation, heart failure, pulmonary embolus, ventricular extrasystoles.

Digestive:Frequent: Vomiting. Infrequent: Flatulence, gingivitis, gum hyperplasia, gastritis, gastroenteritis, stomatitis, cholelithiasis, glossitis, melena, rectal hemorrhage, ulcerative stomatitis, gastro-duodenal ulcer, dysphagia, gum hemorrhage. Rare: Cholangitis, hematemesis, cholecystitis, cholestatic jaundice, colitis, duodenitis, esophagitis, fecal incontinence, mouth ulceration.

Hematologic and Lymphatic:Infrequent: Leukopenia, anemia, immunodeficiency, lymphadenopathy. Rare: Thrombocytopenia, microcytic anemia, petechia.

Metabolic and Nutritional:Infrequent: Peripheral edema, weight gain, edema, thirst, dehydration. Rare: Hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, lactic dehydrogenase increased, SGOT increased, SGPT increased.

Musculoskeletal:Infrequent: Leg cramps, myalgia, myasthenia, arthralgia, arthritis.

Nervous System:Frequent: Tremor, convulsion, abnormal gait, hyperesthesia, incoordination. Infrequent: Hypertonia, twitching, abnormal dreams, vertigo, libido decreased, neuropathy, hyperkinesia, movement disorder, dysarthria, cerebrovascular accident, hypotonia, peripheral neuritis, reflexes increased. Rare: Dyskinesia, dystonia, encephalopathy, facial paralysis, hypokinesia, hyperesthesia, myoclonus, oculogyric crisis.

Behavioral Abnormalities –Non-Psychosis-Related:Infrequent: Euphoria.

Respiratory:Frequent: Pharyngitis, cough increased. Infrequent: Dyspnea. Rare: Apnea, hemoptysis.

Skin and Appendages:Frequent: Pruritus. Infrequent: Maculopapular rash, acne, alopecia, dry skin, sweating, eczema, urticaria, hirsutism, pustular rash, vesiculobullous rash.

Special Senses:Frequent: Amblyopia, tinnitus. Infrequent: Conjunctivitis, parosmia, deafness, visual field defect, glaucoma. Rare: Photophobia, iritis.

Urogenital:Infrequent: Urinary frequency, dysuria, urinary incontinence, hematuria, impotence, urinary retention, urinary urgency, amenorrhea, polyuria, nocturia. Rare: Albuminuria, enuresis, bladder pain, bladder calculus, gynecomastia, mastitis, menorrhagia.

-

POST MARKETING EXPERIENCE

The following serious adverse reactions have been reported since approval and use of zonisamide worldwide. These reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size; therefore, it is not possible to estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, increased creatine phosphokinase.

-

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

The abuse and dependence potential of zonisamide has not been evaluated in human studies (see WARNINGS, Cognitive/Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events subsection). In a series of animal studies, zonisamide did not demonstrate abuse liability and dependence potential. Monkeys did not self-administer zonisamide in a standard reinforcing paradigm. Rats exposed to zonisamide did not exhibit signs of physical dependence of the CNS-depressant type. Rats did not generalize the effects of diazepam to zonisamide in a standard discrimination paradigm after training, suggesting that zonisamide does not have abuse potential of the benzodiazepine-CNS depressant type.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Human Experience:

Experience with zonisamide daily doses over 800 mg/day is limited. During zonisamide clinical development, three patients ingested unknown amounts of zonisamide as suicide attempts, and all three were hospitalized with CNS symptoms. One patient became comatose and developed bradycardia, hypotension, and respiratory depression; the zonisamide plasma level was 100.1 mcg/mL measured 31 hours post-ingestion. Zonisamide plasma levels fell with a half-life of 57 hours, and the patient became alert five days later.

Management:

No specific antidotes for zonisamide overdosage are available. Following a suspected recent overdose, emesis should be induced or gastric lavage performed with the usual precautions to protect the airway. General supportive care is indicated, including frequent monitoring of vital signs and close observation.

Zonisamide has a long half-life (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY section). Due to the low protein binding of zonisamide (40%), renal dialysis may be effective. The effectiveness of renal dialysis as a treatment of overdose has not been formally studied. A poison control center should be contacted for information on the management of zonisamide overdosage.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Zonisamide capsules USP are recommended as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial seizures in adults. Safety and efficacy in pediatric patients below the age of 16 have not been established. Zonisamide capsules USP should be administered once or twice daily, using 25 mg or 100 mg capsules. Zonisamide capsules USP are given orally and can be taken with or without food. Capsules should be swallowed whole.

Adults over Age 16:

The prescriber should be aware that, because of the long half-life of zonisamide, up to two weeks may be required to achieve steady state levels upon reaching a stable dose or following dosage adjustment. Although the regimen described below is one that has been shown to be tolerated, the prescriber may wish to prolong the duration of treatment at the lower doses in order to fully assess the effects of zonisamide at steady state, noting that many of the side effects of zonisamide are more frequent at doses of 300 mg per day and above. Although there is some evidence of greater response at doses above 100 to 200 mg/day, the increase appears small and formal dose-response studies have not been conducted.

The initial dose of zonisamide should be 100 mg daily. After two weeks, the dose may be increased to 200 mg/day for at least two weeks. It can be increased to 300 mg/day and 400 mg/day, with the dose stable for at least two weeks to achieve steady state at each level. Evidence from controlled trials suggests that zonisamide doses of 100 to 600 mg/day are effective, but there is no suggestion of increasing response above 400 mg/day (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Clinical Studies subsection). There is little experience with doses greater than 600 mg/day.

Patients with Renal or Hepatic Disease:

Because zonisamide is metabolized in the liver and excreted by the kidneys, patients with renal or hepatic disease should be treated with caution, and might require slower titration and more frequent monitoring (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY and PRECAUTIONS).

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Zonisamide USP is available as 100 mg two-piece hard gelatin capsules. Zonisamide capsules USP are available in bottles of 30, 60 and 90 as follows:

Dosage Strength

Capsule Description

Pack

NDC #

100 mg

White opaque body and light green cap with ‘G 24’ printed on cap and ‘100’ printed on the body in black ink.

30 count

63187-583-30

30 count

White opaque body and light green cap with ‘G 24’ printed on cap and ‘100’ printed on the body in black ink.

60 count

63187-583-60

60 count

100 mg

White opaque body and light green cap with ‘G 24’ printed on cap and ‘100’ printed on the body in black ink.

90 count

63187-583-90

90 count

- STORAGE AND HANDLING

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

Medication GuideZonisamide Capsules USP

( zoe nis’ a mide )

Read this Medication Guide before you start taking zonisamide capsules and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your medical condition or treatment.

What is the most important information I should know about zonisamide?

Zonisamide may cause serious side effects, including:

- Serious skin rash that can cause death.

- Less sweating and increase in your body temperature (fever).

- Suicidal thoughts or actions in some people.

- Increased level of acid in your blood (metabolic acidosis).

- Problems with your concentration, attention, memory, thinking, speech, or language.

- Blood cell changes such as reduced red and white blood cell counts.

These serious side effects are described below.

- Zonisamide may cause a serious skin rash that can cause death. These serious skin reactions are more likely to happen when you begin taking zonisamide within the first 4 months of treatment but may occur at later times.

- Zonisamide may cause you to sweat less and to increase your body temperature (fever). You may need to be hospitalized for this. You should watch for decreased sweating and fever, especially when it is hot and especially in children taking zonisamide.

Call your health care provider right away if you have:

- a skin rash

- high fever, recurring fever, or long lasting fever

- less sweat than normal

3. Like other antiepileptic drugs, zonisamide may cause suicidal thoughts or actions in a very small number of people, about 1 in 500.

Call a healthcare provider right away if you have any of these symptoms, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you:

- thoughts about suicide or dying

- attempt to commit suicide

- new or worse depression

- new or worse anxiety

- feeling agitated or restless

- panic attacks

- trouble sleeping (insomnia)

- new or worse irritability

- acting aggressive, being angry, or violent

- acting on dangerous impulses

- an extreme increase in activity and talking (mania)

- other unusual changes in behavior or mood

- Suicidal thoughts or actions can be caused by things other than medicines. If you have suicidal thoughts or actions, your healthcare provider may check for other causes.

How can I watch for early symptoms of suicidal thoughts and actions?

- Pay attention to any changes, especially sudden changes, in mood, behaviors, thoughts, or feelings.

- Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider as scheduled.

Call your healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you are worried about symptoms.

Do not stop zonisamide without first talking to a healthcare provider.

Stopping zonisamide suddenly can cause serious problems. Stopping a seizure medicine suddenly in a patient who has epilepsy can cause seizures that will not stop (status epilepticus).

4. Zonisamide can increase the level of acid in your blood (metabolic acidosis). If left untreated, metabolic acidosis can cause brittle or soft bones (osteoporosis, osteomalacia, osteopenia), kidney stones and can slow the rate of growth in children. Metabolic acidosis can happen with or without symptoms.

Sometimes people with metabolic acidosis will:

- feel tired

- not feel hungry (loss of appetite)

- feel changes in heartbeat

- have trouble thinking clearly

Your healthcare provider should do a blood test to measure the level of acid in your blood before and during treatment with zonisamide.

5. Zonisamide may cause problems with your concentration, attention, memory, thinking, speech, or language.

6. Zonisamide can cause blood cell changes such as reduced red and white blood cell counts. Call your healthcare provider if you develop fever, sore throat, sores in your mouth, or unusual bruising.

Zonisamide can have other serious side effects. For more information ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any side effect that bothers you. Be sure to read the section titled “What are the possible side effects of Zonisamide?”

What is zonisamide?

Zonisamide is a prescription medicine that is used with other medicines to treat partial seizures in adults.

It is not known if zonisamide is safe or effective in children under 16 years of age.

Who should not take zonisamide?

Do not take zonisamide if you are allergic to medicines that contain sulfa.

What should I tell my healthcare provider before taking zonisamide?

Before taking zonisamide, tell your healthcare provider about all your medical conditions, including if you:

- have or have had depression, mood problems or suicidal thoughts or behavior

- have kidney problems

- have liver problems

- have a history of metabolic acidosis (too much acid in your blood)

- have weak, brittle bones or soft bones (osteomalacia, osteopenia or osteoporosis)

- have a growth problem

- are on a diet high in fat called a ketogenic diet

- have diarrhea

Tell your healthcare provider if you:

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. Zonisamide may harm your unborn baby. Women who can become pregnant should use effective birth control. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you become pregnant while taking zonisamide.

You and your healthcare provider should decide if you should take zonisamide while you are pregnant.

If you become pregnant while taking zonisamide, talk to your healthcare provider about registering with the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry. You can enroll in this registry by calling 1-888-233-2334. The purpose of this registry is to collect information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy.

- are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Zonisamide can pass into your breast milk. It is not known if zonisamide in your breast milk can harm your baby. Talk to your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby if you take zonisamide.

Tell your healthcare provider about all the medicines you take including prescription and non-prescription medicines, vitamins or herbal supplements. Zonisamide and other medicines may affect each other causing side effects.

Know the medicines you take. Keep a list of them with you to show your healthcare provider and pharmacist each time you get a new medicine.

How should I take zonisamide?

- Take zonisamide exactly as prescribed. Your healthcare prescriber may change your dose. Your healthcare provider will tell you how much zonisamide to take.

- Take zonisamide with or without food.

- Swallow the capsules whole.

- If you take too much zonisamide, call your local Poison Control Center or go to the nearest emergency room right away.

- Do not stop taking zonisamide without talking to your healthcare provider. Stopping zonisamide suddenly can cause serious problems, including seizures that will not stop (status epilepticus).

What should I avoid while taking zonisamide?

- Do not drink alcohol or take other drugs that make you sleepy or dizzy while taking zonisamide until you talk to your health care provider. Zonisamide taken with alcohol or drugs that cause sleepiness or dizziness may make your sleepiness or dizziness worse.

- Do not drive, operate heavy machinery, or do other dangerous activities until you know how zonisamide affects you. Zonisamide can slow your thinking and motor skills.

What are the possible side effects of zonisamide?

Zonisamide can cause serious side effects including:

- The side effects mentioned above (see “What is the most important information I should know about zonisamide?”)

- kidney stones: back pain, stomach pain, or blood in your urine may mean you have kidney stones. Drink plenty of fluids while you take zonisamide to lower your chance of getting kidney stones.

- problems with mood or thinking (new or worse depression; sudden changes in mood, behavior, or loss of contact with reality, sometimes associated with hearing voices or seeing things that are not really there; feeling sleepy or tired; trouble concentrating; speech and language problems).Call your healthcare provider right away if you have any of the symptoms listed above.

The most common side effects of zonisamide include:

- drowsiness

- loss of appetite

- dizziness

- problems with concentration or memory

- trouble with walking and coordination

- agitation or irritability

Side effects can happen at any time, but are more likely to happen during the first several weeks after starting zonisamide.

Tell your healthcare provider about any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away. These are not all of the possible side effects of zonisamide. For more information, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

How should I store zonisamide?

- Store at 25°C (77°F), excursions permitted to 15°-30°C (59°-86°F). [See USP Controlled Room Temperature.]

- Dry and away from light.

Keep zonisamide capsules and all medicines out of the reach of children.

General Information about the safe and effective use of zonisamide

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use zonisamide for a condition for which it was not prescribed. Do not give zonisamide to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them.

This Medication Guide summarizes the most important information about zonisamide. If you would like more information, talk with your healthcare provider. You can ask your pharmacist or healthcare provider for information about zonisamide that is written for health professionals.

For more information, call 1 (888)721-7115.

What are the ingredients in zonisamide capsules?

Active ingredient: zonisamide USP

Inactive ingredients: microcrystalline cellulose, hydrogenated vegetable oil, and sodium lauryl sulfate.

The printed capsule shell of the different strengths is made from the following ingredients:

25 mg - D&C Red #28, FD&C Blue #1, gelatin and titanium dioxide

50 mg - D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Red #40, gelatin and titanium dioxide

100 mg - D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Yellow #6, gelatin and titanium dioxide

The dyes used in the printing ink are FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Blue #2, FD&C Red #40, D&C Yellow #10 aluminium lake and iron oxide black. Additionally, the printing ink also contains n-butyl alcohol, ethanol, propylene glycol and shellac.

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Package/Label Display Panel

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ZONISAMIDE

zonisamide capsuleProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 63187-583(NDC:68462-130) Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ZONISAMIDE (UNII: 459384H98V) (ZONISAMIDE - UNII:459384H98V) ZONISAMIDE 100 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength MICROCRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE (UNII: OP1R32D61U) SODIUM LAURYL SULFATE (UNII: 368GB5141J) GELATIN, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 2G86QN327L) D&C YELLOW NO. 10 (UNII: 35SW5USQ3G) FD&C BLUE NO. 1 (UNII: H3R47K3TBD) FD&C YELLOW NO. 6 (UNII: H77VEI93A8) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) FD&C BLUE NO. 2 (UNII: L06K8R7DQK) FD&C RED NO. 40 (UNII: WZB9127XOA) FERROSOFERRIC OXIDE (UNII: XM0M87F357) BUTYL ALCOHOL (UNII: 8PJ61P6TS3) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) PROPYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 6DC9Q167V3) SHELLAC (UNII: 46N107B71O) Product Characteristics Color GREEN (light green cap) , WHITE (white opaque body) Score no score Shape CAPSULE Size 19mm Flavor Imprint Code G24;100 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 63187-583-30 30 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 12/01/2018 2 NDC: 63187-583-60 60 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 12/01/2018 3 NDC: 63187-583-90 90 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 12/01/2018 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date ANDA ANDA077651 01/30/2006 Labeler - Proficient Rx LP (079196022) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Proficient Rx LP 079502574 REPACK(63187-583) , RELABEL(63187-583)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.