INDOMETHACIN by Chartwell RX, LLC / Chartwell Pharmaceuticals Congers, LLC INDOMETHACIN capsule

INDOMETHACIN by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

INDOMETHACIN by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Chartwell RX, LLC, Chartwell Pharmaceuticals Congers, LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNING: RISK OF SERIOUS CARDIOVASCULAR AND

GASTROINTESTINAL EVENTSCardiovascular Thrombotic Events

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) cause an increased risk of serious cardiovascular thrombotic events, including myocardial infarction and stroke, which can be fatal. This risk may occur early in treatment and may increase with duration of use (see WARNINGS).

- Indomethacin is contraindicated in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery ( see CONTRAINDICATIONS and WARNINGS).

Gastrointestinal Risk

NSAIDs cause an increased risk of serious gastrointestinal adverse events including bleeding, ulceration, and perforation of the stomach or intestines, which can be fatal. These events can occur at any time during use and without warning symptoms. Elderly patients are at greater risk for serious gastrointestinal events. ( See WARNINGS).

-

DESCRIPTION

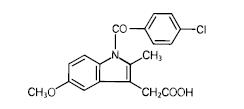

Indomethacin capsules, USP for oral administration contains 25 mg of indomethacin. Each capsule contains the following inactive ingredients: corn starch, croscarmellose sodium, lactose monohydrate, polyethylene glycol 4000, stearic acid, and talc. The capsule shell contains D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Green #3, gelatin, and titanium dioxide. The black imprinting ink contains alcohol, black iron oxide, D&C Yellow #10, FD&C Blue #1, FD&C Blue #2, FD&C Red #40, ferrosoferric oxide, n-butyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and shellac glaze. Indomethacin is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory indole derivative designated chemically as 1 – (4-chlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-1 H-indole-3-acetic acid.

The structural formula is:

Indomethacin is practically insoluble in water and sparingly soluble in alcohol. It has a pKa of 4.5 and is stable in neutral or slightly acidic media and decomposes in strong alkali. The molecular weight of indomethacin is 357.79 and its molecular formula is C 19H 16C 1NO 4

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Indomethacin is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that exhibits antipyretic and analgesic properties. Its mode of action, like that of other anti-inflammatory drugs, is not known. However, its therapeutic action is not due to pituitary-adrenal stimulation.

Indomethacin is a potent inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis in vitro. Concentrations are reached during therapy which have been demonstrated to have an effect in vivo as well. Prostaglandins sensitize afferent nerves and potentiate the action of bradykinin in inducing pain in animal models. Moreover, prostaglandins are known to be among the mediators of inflammation. Since indomethacin is an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis, its mode of action may be due to a decrease of prostaglandins in peripheral tissues.

Indomethacin has been shown to be an effective anti-inflammatory agent, appropriate for long-term use in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and osteoarthritis.

Indomethacin affords relief of symptoms; it does not alter the progressive course of the underlying disease.

Indomethacin suppresses inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis as demonstrated by relief of pain, and reduction of fever, swelling and tenderness. Improvement in patients treated with indomethacin for rheumatoid arthritis has been demonstrated by a reduction in joint swelling, average number of joints involved, and morning stiffness; by increased mobility as demonstrated by a decrease in walking time; and by improved functional capability as demonstrated by an increase in grip strength. Indomethacin may enable the reduction of steroid dosage in patients receiving steroids for the more severe forms of rheumatoid arthritis. In such instances the steroid dosage should be reduced slowly and the patients followed very closely for any possible adverse effects.

Indomethacin has been reported to diminish basal and CO 2 stimulated cerebral blood flow in healthy volunteers following acute oral and intravenous administration. In one study after one week of treatment with orally administered indomethacin, this effect on basal cerebral blood flow had disappeared. The clinical significance of this effect has not been established.

Indomethacin capsules have been found effective in relieving the pain, reducing the fever, swelling, redness, and tenderness of acute gouty arthritis — [see INDICATIONS AND USAGE] .

Following single oral doses of indomethacin capsules 25 mg or 50 mg, indomethacin is readily absorbed, attaining peak plasma concentrations of about 1 and 2 mcg/mL, respectively, at about 2 hours. Orally administered indomethacin capsules are virtually 100% bioavailable, with 90% of the dose absorbed within 4 hours. A single 50 mg dose of indomethacin oral suspension was found to be bioequivalent to a 50 mg indomethacin capsule when each was administered with food.

Indomethacin is eliminated via renal excretion, metabolism, and biliary excretion. Indomethacin undergoes appreciable enterohepatic circulation. The mean half-life of indomethacin is estimated to be about 4.5 hours. With a typical therapeutic regimen of 25 or 50 mg t.i.d., the steady-state plasma concentrations of indomethacin are an average 1.4 times those following the first dose.

Indomethacin exists in the plasma as the parent drug and its desmethyl, desbenzoyl, and desmethyl-desbenzoyl metabolites, all in the unconjugated form. About 60 percent of an oral dosage is recovered in urine as drug and metabolites (26 percent as indomethacin and its glucuronide), and 33 percent is recovered in feces (1.5 percent as indomethacin).

About 99% of indomethacin is bound to protein in plasma over the expected range of therapeutic plasma concentrations. Indomethacin has been found to cross the blood-brain barrier and the placenta.

-

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Carefully consider the potential benefits and risks of indomethacin capsules, USP and other treatment options before deciding to use indomethacin. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals ( see Warnings: Gastrointestinal Bleeding, Ulceration, and Perforation).

Indomethacin has been found effective in active stages of the following:

1. Moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis including acute flares of chronic disease.

2. Moderate to severe ankylosing spondylitis.

3. Moderate to severe osteoarthritis.

4. Acute painful shoulder (bursitis and/or tendinitis).

5. Acute gouty arthritis.

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indomethacin is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to indomethacin or the excipients ( see Warnings; Anaphylactic/Anaphylactoid Reactions) .

Indomethacin should not be given to patients who have experienced asthma, urticaria, or allergic-type reactions after taking aspirin or other NSAIDs. Severe, rarely fatal, anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reactions to NSAIDs have been reported in such patients (see WARNINGS; Anaphylactic/Anaphylactoid Reactions, and PRECAUTIONS; Preexisting Asthma).

- Indomethacin is contraindicated in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery ( see Warnings; Cardiovascular Thrombatic Events).

-

WARNINGS

Cardiovascular Thrombotic Events

Clinical trials of several COX-2 selective and nonselective NSAIDs of up to three years duration have shown an increased risk of serious cardiovascular (CV) thrombotic events, including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, which can be fatal. Based on available data, it is unclear that the risk for CV thrombotic events is similar for all NSAIDs. The relative increase in serious CV thrombotic events over baseline conferred by NSAID use appears to be similar in those with and without known CV disease or risk factors for CV disease. However, patients with known CV disease or risk factors had a higher absolute incidence of excess serious CV thrombotic events, due to their increased baseline rate. Some observational studies found that this increased risk of serious CV thrombotic events began as early as the first weeks of treatment. The increase in CV thrombotic risk has been observed most consistently at higher doses.

To minimize the potential risk for an adverse CV event in NSAID-treated patients, use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. Physicians and patients should remain alert for the development of such events, throughout the entire treatment course, even in the absence of previous CV symptoms. Patients should be informed about the symptoms of serious CV events and the steps to take if they occur.

There is no consistent evidence that concurrent use of aspirin mitigates the increased risk of serious CV thrombotic events associated with NSAID use. The concurrent use of aspirin and an NSAID, such as indomethacin, increases the risk of serious gastrointestinal (GI) events [see WARNINGS].

Status Post Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery

Two large, controlled clinical trials of a COX-2 selective NSAID for the treatment of pain in the first 10–14 days following CABG surgery found an increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke. NSAIDs are contraindicated in the setting of CABG [see CONTRAINDICATIONS ].

Post-MI Patients

Observational studies conducted in the Danish National Registry have demonstrated that patients treated with NSAIDs in the post-MI period were at increased risk of reinfarction, CV-related death, and all-cause mortality beginning in the first week of treatment. In this same cohort, the incidence of death in the first year post MI was 20 per 100 person years in NSAID-treated patients compared to 12 per 100 person years in non-NSAID exposed patients. Although the absolute rate of death declined somewhat after the first year post-MI, the increased relative risk of death in NSAID users persisted over at least the next four years of follow-up.

Avoid the use of indomethacin capsules in patients with a recent MI unless the benefits are expected to outweigh the risk of recurrent CV thrombotic events. If indomethacin capsules are used in patients with a recent MI, monitor patients for signs of cardiac ischemia.

Hypertension

NSAIDs, including indomethacin, can lead to onset of new hypertension or worsening of preexisting hypertension, either of which may contribute to the increased incidence of CV events. Patients taking thiazides or loop diuretics may have impaired response to these therapies when taking NSAIDs. NSAIDs, including indomethacin, should be used with caution in patients with hypertension. Blood pressure (BP) should be monitored closely during the initiation of NSAID treatment and throughout the course of therapy.

Heart Failure and Edema

The Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ Collaboration meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated an approximately two-fold increase in hospitalizations for heart failure in COX-2 selective-treated patients and nonselective NSAID-treated patients compared to placebo-treated patients. In a Danish National Registry study of patients with heart failure, NSAID use increased the risk of MI, hospitalization for heart failure, and death.

Additionally, fluid retention and edema have been observed in some patients treated with NSAIDs. Use of indomethacin may blunt the CV effects of several therapeutic agents used to treat these medical conditions [e.g., diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)] [ see Precautions; Drug Interactions].

Avoid the use of indomethacin capsules in patients with severe heart failure unless the benefits are expected to outweigh the risk of worsening heart failure. If indomethacin capsules are used in patients with severe heart failure, monitor patients for signs of worsening heart failure.

Gastrointestinal Effects – Risk of Ulceration, Bleeding, and Perforation

NSAIDs, including indomethacin, can cause serious gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events including inflammation, bleeding, ulceration, and perforation of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, or large intestine, which can be fatal. These serious adverse events can occur at any time, with or without warning symptoms, in patients treated with NSAIDs. Only one in five patients, who develop a serious upper GI adverse event on NSAID therapy is symptomatic. Upper GI ulcers, gross bleeding, or perforation caused by NSAIDs occur in approximately 1% of patients treated for 3-6 months, and in about 2-4% of patients treated for one year. These trends continue with longer duration of use, increasing the likelihood of developing a serious GI event at some time during the course of therapy. However, even short-term therapy is not without risk.

Rarely, in patients taking indomethacin, intestinal ulceration has been associated with stenosis and obstruction. Gastrointestinal bleeding without obvious ulcer formation and perforation of preexisting sigmoid lesions (diverticulum, carcinoma, etc.) has occurred. Increased abdominal pain in ulcerative colitis patients or the development of ulcerative colitis and regional ileitis have been reported to occur rarely.

NSAIDs should be prescribed with extreme caution in those with prior history of ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with a prior history of peptic ulcer disease and/or gastrointestinalbleeding who use NSAIDs have a greater than 10-fold increased risk for developing a GI bleed compared to patients without these risk factors. Other factors that increase the risk of GI bleeding in patients treated with NSAIDs include longer duration of NSAIDs therapy, concomitant use of oral corticosteroids, aspirin, anticoagulants, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); smoking, use of alcohol, older age, and poor general health status. Most postmarketing reports of fatal GI events occured in elderly or debilitated patients. Additionally, patients with advanced liver disease and/or coagulopathy are at increased risk for GI bleeding.

To minimize the potential risk for an adverse GI event in patients treated with an NSAID, the lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest possible duration. Patients and physicians should remain alert for signs and symptoms of GI ulceration and bleeding during NSAID therapy and promptly initiate additional evaluation and treatment if a serious GI adverse event is suspected. This should include discontinuation of the NSAID until a serious GI adverse event is ruled out. For high risk patients, alternate therapies that do not involve NSAIDs should be considered.

Renal Effects

Long-term administration of NSAIDs has resulted in renal papillary necrosis and other renal injury.

Renal toxicity has also been seen in patients in whom renal prostaglandins have a compensatory role in the maintenance of renal perfusion. In these patients, administration of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may cause a dose-dependent reduction in prostaglandin formation and, secondarily, in renal blood flow, which may precipitate over renal decompensation. Patients at greatest risk of this reaction are those with impaired renal function, heart failure, liver dysfunction, those taking diuretics and ACE inhibitors, patients with volume depletion, and the elderly. Discontinuation of NSAID therapy is usually followed by recovery to the pretreatment state.

It has been reported that the addition of the potassium-sparing diuretic, triamterene, to a maintenance schedule of indomethacin resulted in reversible acute renal failure in two of four healthy volunteers. Indomethacin and triamterene should not be administered together.

Increases in serum potassium concentration, including hyperkalemia, have been reported with use of indomethacin, even in some patients without renal impairment. In patients with normal renal function, these effects have been attributed to a hyporeninemic-hypoaldosteronism state [see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions].

Indomethacin and potassium-sparing diuretics each may be associated with increased serum potassium levels. The potential effects of indomethacin and potassium-sparing diuretics on potassium kinetics and renal function should be considered when these agents are administered concurrently.

Advanced Renal Disease

No information is available from controlled clinical studies regarding the use of indomethacin in patients with advanced renal disease. Therefore, treatment with indomethacin is not recommended in these patients with advanced renal disease. If indomethacin therapy must be initiated, close monitoring of the patient’s renal function is advisable.

Anaphylactic/Anaphylactoid Reactions

As with other NSAIDs, anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reactions may occur in patients without known prior exposure to indomethacin. Indomethacin should not be given to patients with the aspirin triad. This symptom complex typically occurs in asthmatic patients who experience rhinitis with or without nasal polyps, or who exhibit severe, potentially fatal bronchospasm after taking aspirin or other NSAIDs [see CONTRAINDICATIONS and PRECAUTIONS –Preexisting Asthma]. Emergency help should be sought in cases where an anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction occurs.

Skin Reactions

NSAIDs, including indomethacin, can cause serious skin adverse events such as exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens - Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), which can be fatal. These serious events may occur without warning. Patients should be informed about the signs and symptoms of serious skin manifestations and use of the drug should be discontinued at the first appearance of skin rash or any other sign of hypersensitivity.

Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) has been reported in patients taking NSAIDs such as indomethacin capsules. Some of these events have been fatal or life-threatening. DRESS typically, although not exclusively, presents with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and/or facial swelling.

Other clinical manifestations may include hepatitis, nephritis, hematological abnormalities, myocarditis, or myositis. Sometimes symptoms of DRESS may resemble an acute viral infection. Eosinophilia is often present. Because this disorder is variable in its presentation, other organ systems not noted here may be involved. It is important to note that early manifestations of hypersensitivity, such as fever or lymphadenopathy, may be present even though rash is not evident. If such signs or symptoms are present, discontinue indomethacin capsules and evaluate the patient immediately.

Fetal Toxicity

Premature Closure of Fetal Ductus Arteriosus:

Avoid use of NSAIDs, including indomethacin capsules, in pregnant women at about 30 weeks gestation and later. NSAIDs including indomethacin capsules, increase the risk of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus at approximately this gestational age.

Oligohydramnios/Neonatal Renal Impairment:

Use of NSAIDs, including indomethacin capsules, at about 20 weeks gestation or later in pregnancy may cause fetal renal dysfunction leading to oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment. These adverse outcomes are seen, on average, after days to weeks of treatment, although oligohydramnios has been infrequently reported as soon as 48 hours after NSAID initiation. Oligohydramnios is often, but not always, reversible with treatment discontinuation. Complications of prolonged oligohydramnios may, for example, include limb contractures and delayed lung maturation. In some postmarketing cases of impaired neonatal renal function, invasive procedures such as exchange transfusion or dialysis were required.

If NSAID treatment is necessary between about 20 weeks and 30 weeks gestation, limit indomethacin capsules use to the lowest effective dose and shortest duration possible. Consider ultrasound monitoring of amniotic fluid if indomethacin capsules treatment extends beyond 48 hours. Discontinue indomethacin capsules if oligohydramnios occurs and follow up according to clinical practice [ see PRECAUTIONS; Pregnancy].

Ocular Effects

Corneal deposits and retinal disturbances, including those of the macula, have been observed in some patients who had received prolonged therapy with indomethacin. The prescribing physician should be alert to the possible association between the changes noted and indomethacin. It is advisable to discontinue therapy if such changes are observed. Blurred vision may be a significant symptom and warrants a thorough ophthalmological examination. Since these changes may be asymptomatic, ophthalmologic examination at periodic intervals is desirable in patients where therapy is prolonged.

Central Nervous System Effects:

Indomethacin may aggravate depression or other psychiatric disturbances, epilepsy, and parkinsonism, and should be used with considerable caution in patients with these conditions. If severe CNS adverse reactions develop, indomethacin should be discontinued.

Indomethacin may cause drowsiness; therefore, patients should be cautioned about engaging in activities requiring mental alertness and motor coordination, such as driving a car. Indomethacin may also cause headache. Headache which persists despite dosage reduction requires cessation of therapy with indomethacin.

-

PRECAUTIONS

General

Indomethacin cannot be expected to substitute for corticosteroids or to treat corticosteroid insufficiency.

Abrupt discontinuation of corticosteroids may lead to disease exacerbation. Patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy should have their therapy tapered slowly if a decision is made to discontinue corticosteroids.

The pharmacological activity of indomethacin in reducing fever and inflammation may diminish the utility of these diagnostic signs in detecting complications of presumed noninfectious, painful conditions.

Hepatic Effects

Borderline elevations of one or more liver tests may occur in up to 15% of patients taking NSAIDs including indomethacin. These laboratory abnormalities may progress, may remain unchanged, or may be transient with continuing therapy. Notable elevations of ALT or AST (approximately three or more times the upper limit of normal) have been reported in approximately 1% of patients in clinical trials with NSAIDs. In addition, rare cases of severe hepatic reactions, including jaundice and fatal fulminant hepatitis, liver necrosis and hepatic failure, some of them with fatal outcomes have been reported.

A patient with symptoms and/or signs suggesting liver dysfunction, or in whom an abnormal liver test has occurred, should be evaluated for evidence of the development of a more severe hepatic reaction while on therapy with indomethacin. If clinical signs and symptoms consistent with liver disease develop, or if systemic manifestations occur (e.g., eosinophilia, rash, etc.), indomethacin should be discontinued.

Hematological Effects

Anemia is sometimes seen in patients receiving NSAIDs, including indomethacin. This may be due to fluid retention, occult or gross GI blood loss, or an incompletely described effect upon erythropoiesis. Patients on long-term treatment with NSAIDs, including indomethacin, should have their hemoglobin or hematocrit checked if they exhibit any signs or symptoms of anemia.

NSAIDs inhibit platelet aggregation and have been shown to prolong bleeding time in some patients. Unlike aspirin, their effect on platelet function is quantitatively less, of shorter duration, and reversible. Patients receiving indomethacin who may be adversely affected by alterations in platelet function, such as those with coagulation disorders or patients receiving anticoagulants, should be carefully monitored.

Preexisting Asthma

Patients with asthma may have aspirin-sensitive asthma. The use of aspirin in patients with aspirin-sensitive

asthma has been associated with severe bronchospasm which can be fatal. Since cross reactivity, including bronchospasm, between aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reported in such aspirin-sensitive patients, indomethacin should not be administered to patients with this form of aspirin sensitivity and should be used with caution in patients with preexisting asthma.

Information for Patients

Patients should be informed of the following information before initiating therapy with an NSAID and periodically during the course of ongoing therapy. Patients should also be encouraged to read the NSAID Medication Guide that accompanies each prescription dispensed.

-

Cardiovascular Thrombotic Events

Advise patients to be alert for the symptoms of cardiovascular thrombotic events, including chest pain, shortness of breath, weakness, or slurring of speech, and to report any of these symptoms to their health care provider immediately [ see WARNINGS]. - Indomethacin, like other NSAIDs, can cause GI discomfort and, rarely, serious GI side effects, such as ulcers and bleeding, which may result in hospitalization and even death. Although serious GI tract ulcerations and bleeding can occur without warning symptoms, patients should be alert for the signs and symptoms of ulcerations and bleeding, and should ask for medical advice when observing any indicative sign or symptoms including epigastric pain, dyspepsia, melena, and hematemesis. Patients should be apprised of the importance of this follow-up [see WARNINGS, Gastrointestinal Effects - Risk of Ulceration, Bleeding, and Perforation].

-

Serious Skin Reactions, including DRESS

Advise patients to stop taking indomethacin capsules immediately if they develop any type of rash or fever and to contact their healthcare provider as soon as possible [see WARNINGS]. -

Heart Failure And Edema

Advise patients to be alert for the symptoms of congestive heart failure including shortness of breath, unexplained weight gain, or edema and to contact their healthcare provider if such symptoms occur [see WARNINGS]. - Patients should be informed of the warning signs and symptoms of hepatotoxicity (e.g., nausea, fatigue, lethargy, pruritus, jaundice, right upper quadrant tenderness, and “flu-like” symptoms). If these occur, patients should be instructed to stop therapy and seek immediate medical therapy.

- Patients should be informed of the signs of an anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction (e.g. difficulty breathing, swelling of the face or throat). If these occur, patients should be instructed to seek immediate emergency help [see WARNINGS].

-

Fetal Toxicity

Inform pregnant women to avoid use of indomethacin capsules and other NSAIDs starting at 30 weeks gestation because of the risk of the premature closing of the fetal ductus arteriosus. If treatment with indomethacin capsules is needed for a pregnant woman between about 20 to 30 weeks gestation, advise her that she may need to be monitored for oligohydramnios, if treatment continues for longer than 48 hours [see WARNINGS; Fetal Toxicity, PRECAUTIONS; Pregnancy].

Laboratory Tests

Because serious GI tract ulcerations and bleeding can occur without warning symptoms, physicians should monitor for signs or symptoms of GI bleeding. Patients on long-term treatment with NSAIDs should have their CBC and a chemistry profile checked periodically. If clinical signs and symptoms consistent with liver or renal disease develop, systemic manifestations occur (e.g., eosinophilia, rash, etc.) or if abnormal liver tests persist or worsen, indomethacin should be discontinued.

Drug Interactions

ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Antagonists

Reports suggest that NSAIDs may diminish the antihypertensive effect of ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin II antagonists. Indomethacin can reduce the antihypertensive effects of captopril and losartan. These interactions should be given consideration in patients taking NSAIDs concomitantly with ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin II antagonists. In some patients with compromised renal function, the co-administration of an NSAID and an ACE-inhibitor or an angiotensin II antagonist may result in further deterioration of renal function, including possible acute renal failure, which is usually reversible.

Aspirin

When indomethacin is administered with aspirin, its protein binding is reduced, although the clearance of free indomethacin is not altered. The clinical significance of this interaction is not known.

The use of indomethacin in conjunction with aspirin or other salicylates is not recommended. Controlled clinical studies have shown that the combined use of indomethacin and aspirin does not produce any greater therapeutic effect than the use of indomethacin alone. In a clinical study of the combined use of indomethacin and aspirin, the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects was significantly increased with combined therapy.

In a study in normal volunteers, it was found that chronic concurrent administration of 3.6 g of aspirin per day decreases indomethacin blood levels approximately 20%.

Indomethacin is not a substitute for low dose aspirin for cardiovascular protection.

Beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents

Blunting of the antihypertensive effect of beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including indomethacin has been reported. Therefore, when using these blocking agents to treat hypertension, patients should be observed carefully in order to confirm that the desired therapeutic effect has been obtained.

Cyclosporine

Administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs concomitantly with cyclosporine has been associated with an increase in cyclosporine-induced toxicity, possibly due to decreased synthesis of renal prostacyclin. NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients taking cyclosporine, and renal function should be carefully monitored.

Diflunisal

In normal volunteers receiving indomethacin, the administration of diflunisal decreased the renal clearance and significantly increased the plasma levels of indomethacin. In some patients, combined use of indomethacin and diflunisal has been associated with fatal gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Therefore, diflunisal and indomethacin should not be used concomitantly.

Digoxin

Indomethacin given concomitantly with digoxin has been reported to increase the serum concentration and prolong the half-life of digoxin. Therefore, when indomethacin and digoxin are used concomitantly, serum digoxin levels should be closely monitored.

Diuretics

In some patients, the administration of indomethacin can reduce the diuretic, natriuretic, and antihypertensive effects of loop, potassium-sparing, and thiazide diuretics. This response has been attributed to inhibition of renal prostaglandin synthesis.

Indomethacin reduces basal plasma renin activity (PRA), as well as those elevations of PRA induced by furosemide administration, or salt or volume depletion. These facts should be considered when evaluating plasma renin activity in hypertensive patients.

It has been reported that the addition of triamterene to a maintenance schedule of indomethacin resulted in reversible acute renal failure in two of four healthy volunteers. Indomethacin and triamterene should not be administered together.

Indomethacin and potassium-sparing diuretics each may be associated with increased serum potassium levels. The potential effects of indomethacin and potassium-sparing diuretics on potassium kinetics and renal function should be considered when these agents are administered concurrently.

Most of the above effects concerning diuretics have been attributed, at least in part, to mechanisms involving inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by indomethacin.

During concomitant therapy with NSAIDs, the patient should be observed closely for signs of renal failure (see WARNINGS, Renal Effects), as well as to assure diuretic efficacy.

Lithium

Indomethacin capsules 50 mg t.i.d. produced a clinically relevant elevation of plasma lithium and reduction in renal lithium clearance in psychiatric patients and normal subjects with steady state plasma lithium concentrations. This effect has been attributed to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. As a consequence, when NSAIDs and lithium are given concomitantly, the patient should be carefully observed for signs of lithium toxicity. (Read circulars for lithium preparations before use of such concomitant therapy.) In addition, the frequency of monitoring serum lithium concentration should be increased at the outset of such combination drug treatment.

Methotrexate

NSAIDs have been reported to competitively inhibit methotrexate accumulation in rabbit kidney slices.

This may indicate that they could enhance the toxicity of methotrexate. Caution should be used when NSAIDs are administered concomitantly with methotrexate.

NSAIDs

The concomitant use of indomethacin with other NSAIDs is not recommended due to the increased possibility of gastrointestinal toxicity, with little or no increase in efficacy.

Oral anticoagulants

Clinical studies have shown that indomethacin does not influence the hypoprothrombinemia produced by anticoagulants. However, when any additional drug, including indomethacin, is added to the treatment of patients on anticoagulant therapy, the patients should be observed for alterations of the prothrombin time. In post-marketing experience, bleeding has been reported in patients on concomitant treatment with anticoagulants and indomethacin. Caution should be exercised when indomethacin and anticoagulants are administered concomitantly. The effects of warfarin and NSAIDs on GI bleeding are synergistic, such that users of both drugs together have a risk of serious GI bleeding higher than users of either drug alone.

Probenecid

When indomethacin is given to patients receiving probenecid, the plasma levels of indomethacin are likely to be increased. Therefore, a lower total daily dosage of indomethacin may produce a satisfactory therapeutic effect. When increases in the dose of indomethacin are made, they should be made carefully and in small increments.

Drug/Laboratory Test Interactions

False-negative results in the dexamethasone suppression test (DST) in patients being treated with indomethacin have been reported. Thus, results of the DST should be interpreted with caution in these patients.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

In an 81-week chronic oral toxicity study in the rat at doses up to 1 mg/kg/day (0.05 times the maximum recommended human daily dose (MRHD) of 200 mg/day based on a mg/m 2 basis), indomethacin had no tumorigenic effect. Indomethacin produced no neoplastic or hyperplastic changes related to treatment in carcinogenic studies in the rat (dosing period 73 to 110 weeks) and the mouse (dosing period 62 to 88 weeks) at doses up to 1.5 mg/kg/day (0.04 times and 0.07 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis, respectively) .

Mutagenesis

Indomethacin did not have any mutagenic effect in in vitro bacterial tests and a series of in vivo tests including the host-mediated assay, sex-linked recessive lethals in Drosophila, and the micronucleus test in mice.

Impairment of Fertility

Indomethacin at dosage levels up to 0.5 mg/kg/day had no effect on fertility in mice in a two generation reproduction study (0.01 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis) or a two litter reproduction study in rats (0.02 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis).

Pregnancy

Risk Summary

Use of NSAIDs, including indomethacin capsules, can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus and fetal renal dysfunction leading to oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment. Because of these risks, limit dose and duration of indomethacin capsules use between about 20 and 30 weeks of gestation, and avoid indomethacin capsules use at about 30 weeks of gestation and later in pregnancy [ see WARNINGS; Fetal Toxicity].

Premature Closure of Fetal Ductus Arteriosus

Use of NSAIDs, including indomethacin capsules, at about 30 weeks gestation or later in pregnancy increases the risk of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus.

Oligohydramnios/Neonatal Renal Impairment

Use of NSAIDs at about 20 weeks gestation or later in pregnancy has been associated with cases of fetal renal dysfunction leading to oligohydramnios, and in some cases, neonatal renal impairment.

Data from observational studies regarding other potential embryofetal risks of NSAID use in women in the first or second trimesters of pregnancy are inconclusive. In the general U.S. population, all clinically recognized pregnancies, regardless of drug exposure, have a background rate of 2-4% for major malformations, and 15-20% for pregnancy loss. In animal reproduction studies retarded fetal ossification was observed with administration of indomethacin to mice and rats during organogenesis at doses 0.1 and 0.2 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD, 200 mg). In published studies in pregnant mice, indomethacin produced maternal toxicity and death, increased fetal resorptions, and fetal malformations at 0.1 times the MRHD. When rat and mice dams were dosed during the last three days of gestation, indomethacin produced neuronal necrosis in the offspring at 0.1 and 0.05 times the MRHD, respectively [see Data]. Based on animal data, prostaglandins have been shown to have an important role in endometrial vascular permeability, blastocyst implantation, and decidualization. In animal studies, administration of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors such as indomethacin, resulted in increased pre- and post-implantation loss. Based on animal data, prostaglandins have been shown to have an important role in endometrial vascular permeability, blastocyst implantation, and decidualization. In animal studies, administration of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors such as indomethacin, resulted in increased pre- and post-implantation loss. Prostaglandins also have been shown to have an important role in fetal kidney development. In published animal studies, prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors have been reported to impair kidney development when administered at clinically relevant doses.

Data

Animal Data

Reproductive studies were conducted in mice and rats at dosages of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/kg/day.

Except for retarded fetal ossification at 4 mg/kg/day considered secondary to the decreased average fetal weights, no increase in fetal malformations was observed as compared with control groups. Other studies in mice reported in the literature using higher doses (5 to 15 mg/kg/day) have described maternal toxicity and death, increased fetal resorptions, and fetal malformations.

In rats and mice, maternal indomethacin administration of 4.0 mg/kg/day (0.2 times and 0.1 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis) during the last 3 days of gestation was associated with an increased incidence of neuronal necrosis in the diencephalon in the live-born fetuses, however, no increase in neuronal necrosis was observed at 2.0 mg/kg/day as compared to the control groups (0.1 times and 0.05 times the MRHD on a mg/m 2 basis). Administration of 0.5 or 4.0 mg/kg/day to offspring during the first 3 days of life did not cause an increase in neuronal necrosis at either dose level.

Clinical Considerations

Fetal/Neonatal Adverse Reactions

Premature Closure of Fetal Ductus Arteriosus:

Avoid use of NSAIDs in women at about 30 weeks gestation and later in pregnancy, because NSAIDs, including indomethacin capsules, can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus (see WARNINGS; Fetal Toxicity) .

Oligohydramnios/Neonatal Renal Impairment

If an NSAID is necessary at about 20 weeks gestation or later in pregnancy, limit the use to the lowest effective dose and shortest duration possible. If indomethacin capsules treatment extends beyond 48 hours, consider monitoring with ultrasound for oligohydramnios. If oligohydramnios occurs, discontinue indomethacin capsules and follow up according to clinical practice (see WARNINGS; Fetal Toxicity).

Data

Human Data

Premature Closure of Fetal Ductus Arteriosus:

Published literature reports that the use of NSAIDs at about 30 weeks of gestation and later in pregnancy may cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus.

Oligohydramnios/Neonatal Renal Impairment:

Published studies and postmarketing reports describe maternal NSAID use at about 20 weeks gestation or later in pregnancy associated with fetal renal dysfunction leading to oligohydramnios, and in some cases, neonatal renal impairment. These adverse outcomes are seen, on average, after days to weeks of treatment, although oligohydramnios has been infrequently reported as soon as 48 hours after NSAID initiation. In many cases, but not all, the decrease in amniotic fluid was transient and reversible with cessation of the drug. There have been a limited number of case reports of maternal NSAID use and neonatal renal dysfunction without oligohydramnios, some of which were irreversible. Some cases of neonatal renal dysfunction required treatment with invasive procedures, such as exchange transfusion or dialysis.

Methodological limitations of these postmarketing studies and reports include lack of a control group; limited information regarding dose, duration, and timing of drug exposure; and concomitant use of other medications. These limitations preclude establishing a reliable estimate of the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes with maternal NSAID use. Because the published safety data on neonatal outcomes involved mostly preterm infants, the generalizability of certain reported risks to the full-term infant exposed to NSAIDs through maternal use is uncertain.

Labor and Delivery

There are no studies on the effects of indomethacin capsules during labor and delivery. In animal studies, NSAIDs, including indomethacin, inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, caused delayed parturition, and increase the incidence of stillbirths.

Use in Nursing Mothers

Indomethacin is excreted in the milk of lactating mothers. The development and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for indomethacin capsules and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from the indomethacin capsules or from the underlying maternal condition.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients 14 years of age and younger has not been established. Indomethacin should not be prescribed for pediatric patients 14 years of age and younger unless toxicity or lack of efficacy associated with other drugs warrants the risk.

In experience with more than 900 pediatric patients reported in the literature or to the manufacturer who were treated with indomethacin capsules, side effects in pediatric patients were comparable to those reported in adults. Experience in pediatric patients has been confined to the use of indomethacin capsules.

If a decision is made to use indomethacin for pediatric patients two years of age or older, such patients should be monitored closely and periodic assessment of liver function is recommended. There have been cases of hepatotoxicity reported in pediatric patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, including fatalities. If indomethacin treatment is instituted, a suggested starting dose is 1-2 mg/kg/day given in divided doses. Maximum daily dosage should not exceed 3 mg/kg/day or 150-200 mg/day, whichever is less. Limited data are available to support the use of a maximum daily dosage of 4 mg/kg/day or 150-200 mg/day, whichever is less. As symptoms subside, the total daily dosage should be reduced to the lowest level required to control symptoms, or the drug should be discontinued.

Geriatric Use

As with any NSAID, caution should be exercised in treating the elderly (65 years and older) since advancing age appears to increase the possibility of adverse reactions [see WARNINGS, Gastrointestinal Effects - Risk of Ulceration, Bleeding, and Perforation and DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION]. Elderly patients seem to tolerate ulceration or bleeding less well than other individuals and many spontaneous reports of fatal GI events are in this population [see WARNINGS, Gastrointestinal Effects - Risk of Ulceration, Bleeding, and Perforation].

Indomethacin may cause confusion or, rarely, psychosis [see ADVERSE REACTIONS]; physicians should remain alert to the possibility of such adverse effects in the elderly.

This drug is known to be substantially excreted by the kidney and the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, care should be taken in dose selection and it may be useful to monitor renal function [see WARNINGS, Renal Effects].

-

Cardiovascular Thrombotic Events

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The adverse reactions for indomethacin capsules listed in the following table have been arranged into two groups: (1) incidence greater than 1%; and (2) incidence less than 1%. The incidence for group (1) was obtained from 33 double-blind controlled clinical trials reported in the literature (1,092 patients). The incidence for group (2) was based on reports in clinical trials, in the literature, and on voluntary reports since marketing. The probability of a causal relationship exists between indomethacin and these adverse reactions, some of which have been reported only rarely.

Incidence greater than 1%

Incidence less than 1%

GASTROINTESTINAL

nausea * with or without vomiting

dyspepsia * (including indigestion, heartburn and epigastric pain)

diarrhea

abdominal distress or pain

constipation

anorexia

bloating (includes distension)

flatulence

peptic ulcer

gastroenteritis

rectal bleeding

proctitis

single or multiple ulcerations,

including perforation and hemorrhage of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum or small and large intestinesintestinal ulceration associated with stenosis and obstruction

gastrointestinal bleeding without obvious ulcer formation and perforation of pre-existing sigmoid lesions (diverticulum, carcinoma, etc.) development of ulcerative colitis and regional ileitis

ulcerative stomatitis

toxic hepatitis and jaundice (some fatal cases have been reported)

intestinal strictures (diaphragms)

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

headache (11.7%)

dizziness *

vertigo

somnolence

depression and fatigue

(including malaise and listlessness)anxiety (includes nervousness)

muscle weakness

involuntary muscle movements

insomnia

muzziness

psychic disturbances including psychotic episodes

mental confusion

drowsiness

light-headedness

syncope

paresthesia

aggravation of epilepsy and parkinsonism

depersonalization

coma

peripheral neuropathy

convulsion

dysarthria

SPECIAL SENSES

tinnitus

ocular- corneal deposits and retinal disturbances, including those of the macula, have been reported in some patients on prolonged therapy with indomethacin

blurred vision

diplopia

hearing disturbances, deafness

CARDIOVASCULAR

None

hypertension

hypotension

tachycardia

chest pain

congestive heart failure

arrhythmia; palpitations

METABOLIC

None

edema

weight gain

fluid retention

flushing or sweating

hyperglycemia

glycosuria

hyperkalemia

INTEGUMENTARY

None

pruritus

rash; urticaria

petechiae or ecchymosis

exfoliative dermatitis

erythema nodosum

loss of hair

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

erythema multiforme

toxic epidermal necrolysis

HEMATOLOGIC

None

leukopenia

bone marrow depression

anemia secondary to obvious or occult gastrointestinal bleeding

aplastic anemia

hemolytic anemia

agranulocytosis

thrombocytopenic purpura

disseminated intravascular coagulation

HYPERSENSITIVITY

None

acute anaphylaxis

acute respiratory distress

rapid fall in blood pressure resembling a shock-like state

angioedema

dyspnea

asthma

purpura

angiitis

pulmonary edema

fever

GENITOURINARY

None

hematuria

vaginal bleeding

proteinuria

nephrotic syndrome

interstitial nephritis

BUN elevation

renal insufficiency, including renal failure

MISCELLANEOUS

None

epistaxis

breast changes, including enlargement and tenderness, or gynecomastia

* Reactions occurring in 3% to 9% of patients treated with indomethacin capsules. (Those reactions occurring in less than 3% of the patients are unmarked.)

Causal relationship unknown: Other reactions have been reported but occurred under circumstances where a causal relationship could not be established. However, in these rarely reported events, the possibility cannot be excluded. Therefore, these observations are being listed to serve as alerting information to physicians:

Cardiovascular: Thrombophlebitis

Hematologic: Although there have been several reports of leukemia, the supporting information is weak

Genitourinary: Urinary frequency.

A rare occurrence of fulminant necrotizing fasciitis, particularly in association with Group A β hemolytic streptococcus, has been described in persons treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, including indomethacin, sometimes with fatal outcome [see also PRECAUTIONS, General].

-

OVERDOSAGE

The following symptoms may be observed following overdosage: nausea, vomiting, intense headache, dizziness, mental confusion, disorientation, or lethargy. There have been reports of paresthesias, numbness, and convulsions.

Treatment is symptomatic and supportive. The stomach should be emptied as quickly as possible if the ingestion is recent. If vomiting has not occurred spontaneously, the patient should be induced to vomit with syrup of ipecac. If the patient is unable to vomit, gastric lavage should be performed. Once the stomach has been emptied, 25 or 50 g of activated charcoal may be given. Depending on the condition of the patient, close medical observation and nursing care may be required. The patient should be followed for several days because gastrointestinal ulceration and hemorrhage have been reported as adverse reactions of indomethacin. Use of antacids may be helpful.

The oral LD 50 of indomethacin in mice and rats (based on 14 day mortality response) was 50 and 12 mg/kg, respectively.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Carefully consider the potential benefits and risks of indomethacin and other treatment options before deciding to use indomethacin . Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals [see WARNINGS].

After observing the response to initial therapy with indomethacin, the dose and frequency should be adjusted to suit an individual patient’s needs.

Indomethacin is available as 25 mg capsules

Adverse reactions appear to correlate with the size of the dose of indomethacin in most patients but not all. Therefore, every effort should be made to determine the smallest effective dosage for the individual patient.

Pediatric Use

Indomethacin ordinarily should not be prescribed for pediatric patients 14 years of age and under (see PRECAUTIONS, Pediatric Use).

Adult Use

Dosage Recommendations for Active Stages of the Following:

- Moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis including acute flares of chronic disease; moderate to severe ankylosing spondylitis; and moderate to severe osteoarthritis.

Suggested Dosage:

Indomethacin capsules 25 mg b.i.d. or t.i.d. If this is well tolerated, increase the daily dosage by 25 or by 50 mg, if required by continuing symptoms, at weekly intervals until a satisfactory response is obtained or until a total daily dose of 150-200 mg is reached. DOSES ABOVE THIS AMOUNT GENERALLY DO NOT INCREASE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE DRUG.

In patients who have persistent night pain and/or morning stiffness, the giving of a large portion, up to a maximum of 100 mg, of the total daily dose at bedtime may be helpful in affording relief. The total daily dose should not exceed 200 mg. In acute flares of chronic rheumatoid arthritis, it may be necessary to increase the dosage by 25 mg or, if required, by 50 mg daily.

If minor adverse effects develop as the dosage is increased, reduce the dosage rapidly to a tolerated dose and OBSERVE THE PATIENT CLOSELY.

If severe adverse reactions occur, STOP THE DRUG. After the acute phase of the disease is under control, an attempt to reduce the daily dose should be made repeatedly until the patient is receiving the smallest effective dose or the drug is discontinued.

Careful instructions to, and observations of, the individual patient are essential to the prevention of serious, irreversible, including fatal, adverse reactions.

As advancing years appear to increase the possibility of adverse reactions, indomethacin should be used with greater care in the elderly [see PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use].

2. Acute painful shoulder (bursitis and/or tendinitis).

Initial Dose:

75-150 mg daily in 3 or 4 divided doses.

The drug should be discontinued after the signs and symptoms of inflammation have been controlled for several days. The usual course of therapy is 7-14 days.

3. Acute gouty arthritis.

Suggested Dosage:

Indomethacin capsules 50 mg t.i.d. until pain is tolerable. The dose should then be rapidly reduced to complete cessation of the drug. Definite relief of pain has been reported within 2 to 4 hours.

Tenderness and heat usually subside in 24 to 36 hours, and swelling gradually disappears in 3 to 5 days.

- Moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis including acute flares of chronic disease; moderate to severe ankylosing spondylitis; and moderate to severe osteoarthritis.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

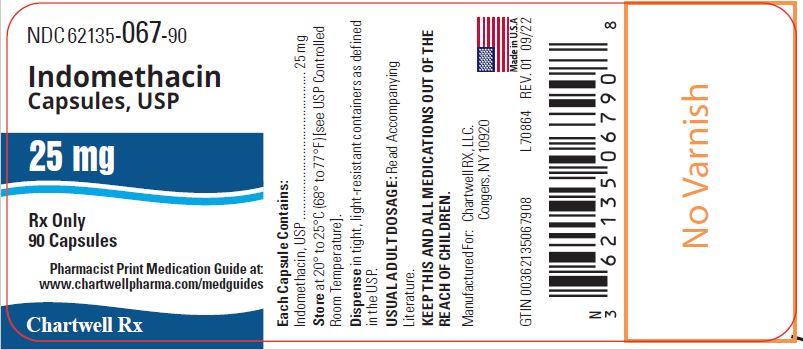

Indomethacin Capsules, USP are available containing 25 mg of indomethacin.

The 25 mg (green/green) capsules are imprinted “CE” in black ink on cap and imprinted “57” in black ink on body, filled with white powder and are supplied in bottles of 90 (NDC: 62135-067-90), 180 (NDC: 62135-067-18) Capsules.

Store at 20˚ to 25˚C (68˚ to 77˚F) [see USP controlled room temperature].

Manufactured for:

Chartwell RX, LLC.

Congers, NY 10920

L71083

Rev. 09/2022 -

MEDICATION GUIDE

Medication Guide for Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

What is the most important information I should know about medicines called Nonsteroidal Anti- inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)?

NSAIDs can cause serious side effects, including:

-

Increased risk of a heart attack or stroke that can lead to death. This risk may happen early in treatment and may increase:

- with increasing doses of NSAIDs

- with longer use of NSAIDs

Do not take NSAIDs right before or after a heart surgery called a “coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)."

Avoid taking NSAIDs after a recent heart attack, unless your healthcare provider tells you to. You may have an increased risk of another heart attack if you take NSAIDs after a recent heart attack.

-

Increased risk of bleeding, ulcers, and tears (perforation) of the esophagus (tube leading from the mouth to the stomach), stomach and intestines:

- anytime during use

- without warning symptoms

- that may cause death

The risk of getting an ulcer or bleeding increases with:

- past history of stomach ulcers, or stomach or intestinal bleeding with use of NSAIDs

- taking medicines called “corticosteroids”, “anticoagulants”, “SSRIs”, or “SNRIs”

- increasing doses of NSAIDs o older age

- longer use of NSAIDs o poor health

- smoking o advanced liver disease

- drinking alcohol o bleeding problems

NSAIDs should only be used:

- exactly as prescribed

- at the lowest dose possible for your treatment

- for the shortest time needed

What are NSAIDs?

NSAIDs are used to treat pain and redness, swelling, and heat (inflammation) from medical conditions such as different types of arthritis, menstrual cramps, and other types of short-term pain.

Who should not take NSAIDs?

Do not take NSAIDs:

- if you have had an asthma attack, hives, or other allergic reaction with aspirin or any other NSAIDs.

- right before or after heart bypass surgery.

Before taking NSAIDS, tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, including if you:

- have liver or kidney problems

- have high blood pressure

- have asthma

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. Taking NSAIDs at about 20 weeks of pregnancy or later may harm your unborn baby. If you need to take NSAIDs for more than 2 days when you are between 20 and 30 weeks of pregnancy, your healthcare provider may need to monitor the amount of fluid in your womb around your baby. You should not take NSAIDs after 29 weeks of pregnancy.

- are breastfeeding or plan to breast feed.

Tell your healthcare provider about all of the medicines you take, including prescription or over-the-counter medicines, vitamins or herbal supplements. NSAIDs and some other medicines can interact with each other and cause serious side effects. Do not start taking any new medicine without talking to your healthcare provider first.

What are the possible side effects of NSAIDs?

NSAIDs can cause serious side effects, including:

See “What is the most important information I should know about medicines called Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)?

- new or worse high blood pressure

- heart failure

- liver problems including liver failure

- kidney problems including kidney failure

- low red blood cells (anemia)

- life-threatening skin reactions

- life-threatening allergic reactions

- Other side effects of NSAIDs include: stomach pain, constipation, diarrhea, gas, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness.

Get emergency help right away if you get any of the following symptoms:

- shortness of breath or trouble breathing slurred speech

- chest pain swelling of the face or throat

- weakness in one part or side of your body

Stop taking your NSAID and call your healthcare provider right away if you get any of the following symptoms:

- nausea vomit blood

- more tired or weaker than usual there is blood in your bowel movement or it is black and sticky like tar

- diarrhea unusual weight gain

- itching skin rash or blisters with fever

- your skin or eyes look yellow swelling of the arms, legs, hands and feet

- indigestion or stomach pain

- flu-like symptoms

If you take too much of your NSAID, call your healthcare provider or get medical help right away. These are not all the possible side effects of NSAIDs. For more information, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist about NSAIDs.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

Other information about NSAIDs

- Aspirin is an NSAID but it does not increase the chance of a heart attack. Aspirin can cause bleeding in the brain, stomach, and intestines. Aspirin can also cause ulcers in the stomach and intestines.

- Some NSAIDs are sold in lower doses without a prescription (over-the counter). Talk to your healthcare provider before using over-the-counter NSAIDs for more than 10 days.

General information about the safe and effective use of NSAIDs

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use NSAIDs for a condition for which it was not prescribed. Do not give NSAIDs to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them.

If you would like more information about NSAIDs, talk with your healthcare provider. You can ask your pharmacist or healthcare provider for information about NSAIDs that is written for health professionals.

Manufactured for: Chartwell RX, LLC, Congers, NY 10920

For more information, contact Chartwell RX, LLC at 845-232-1683.

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Revised: 09/2022

L71084

-

Increased risk of a heart attack or stroke that can lead to death. This risk may happen early in treatment and may increase:

-

PACKAGE LABEL-PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

Indomethacin Capsules, USP 25 mg - NDC: 62135-067-90 - 90 Capsules Label

Indomethacin Capsules, USP 25 mg - NDC: 62135-067-18 - 180 Capsules Label

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

INDOMETHACIN

indomethacin capsuleProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 62135-067 Route of Administration ORAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength INDOMETHACIN (UNII: XXE1CET956) (INDOMETHACIN - UNII:XXE1CET956) INDOMETHACIN 25 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength STARCH, CORN (UNII: O8232NY3SJ) CROSCARMELLOSE SODIUM (UNII: M28OL1HH48) LACTOSE MONOHYDRATE (UNII: EWQ57Q8I5X) POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL 4000 (UNII: 4R4HFI6D95) STEARIC ACID (UNII: 4ELV7Z65AP) TALC (UNII: 7SEV7J4R1U) D&C YELLOW NO. 10 (UNII: 35SW5USQ3G) FD&C GREEN NO. 3 (UNII: 3P3ONR6O1S) GELATIN, UNSPECIFIED (UNII: 2G86QN327L) TITANIUM DIOXIDE (UNII: 15FIX9V2JP) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) FD&C BLUE NO. 1 (UNII: H3R47K3TBD) FD&C BLUE NO. 2 (UNII: L06K8R7DQK) FD&C RED NO. 40 (UNII: WZB9127XOA) FERROSOFERRIC OXIDE (UNII: XM0M87F357) BUTYL ALCOHOL (UNII: 8PJ61P6TS3) PROPYLENE GLYCOL (UNII: 6DC9Q167V3) SHELLAC (UNII: 46N107B71O) Product Characteristics Color green (opaque cap and body) Score no score Shape CAPSULE Size 16mm Flavor Imprint Code CE;57 Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 62135-067-90 90 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 09/30/2022 2 NDC: 62135-067-18 180 in 1 BOTTLE; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 09/30/2022 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA authorized generic NDA018829 08/06/1984 Labeler - Chartwell RX, LLC (079394054)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.