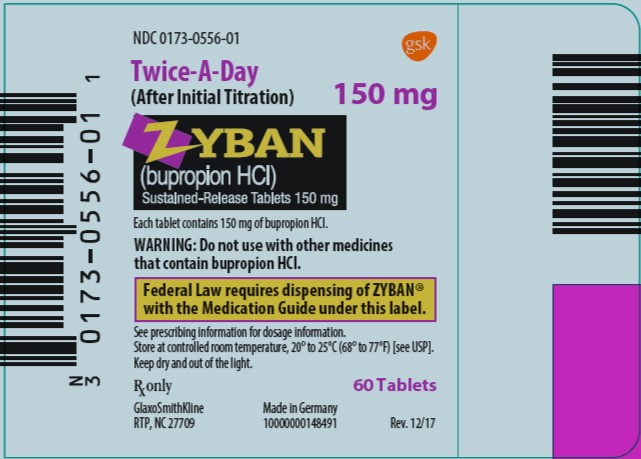

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use ZYBAN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ZYBAN. ZYBAN® (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained-release tablets for oral useInitial U.S. Approval: 1985

ZYBAN by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

ZYBAN by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by GlaxoSmithKline LLC. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

ZYBAN- bupropion hydrochloride tablet, film coated

GlaxoSmithKline LLC

----------

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATIONThese highlights do not include all the information needed to use ZYBAN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ZYBAN.

ZYBAN® (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained-release tablets for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1985 WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORSSee full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.INDICATIONS AND USAGEZYBAN is an aminoketone agent indicated as an aid to smoking cessation treatment. (1) DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

ADVERSE REACTIONSMost common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and ≥1% more than placebo rate) are: insomnia, rhinitis, dry mouth, dizziness, nervous disturbance, anxiety, nausea, constipation, and arthralgia. (6.1) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact GlaxoSmithKline at 1-888-825-5249 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch DRUG INTERACTIONS

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide. Revised: 7/2019 |

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

SUICIDALITY AND ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

Although ZYBAN is not indicated for treatment of depression, it contains the same active ingredient as the antidepressant medications WELLBUTRIN®, WELLBUTRIN® SR, and WELLBUTRIN XL®. Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term trials. These trials did not show an increase in the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant use in subjects over age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressant use in subjects aged 65 and older [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

In patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy, monitor closely for worsening, and for emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Advise families and caregivers of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Usual Dosage

Treatment with ZYBAN should be initiated before the patient’s planned quit day, while the patient is still smoking, because it takes approximately 1 week of treatment to achieve steady-state blood levels of bupropion. The patient should set a “target quit date” within the first 2 weeks of treatment with ZYBAN.

Dosing

To minimize the risk of seizure:

- Begin dosing with one 150-mg tablet per day for 3 days.

- Increase dose to 300 mg per day given as one 150-mg tablet twice each day with an interval of at least 8 hours between each dose.

- Do not exceed 300 mg per day.

ZYBAN should be swallowed whole and not crushed, divided, or chewed, as this may lead to an increased risk of adverse effects including seizures [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

ZYBAN may be taken with or without food [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.2 Duration of Treatment

Treatment with ZYBAN should be continued for 7 to 12 weeks. If the patient has not quit smoking after 7 to 12 weeks, it is unlikely that he or she will quit during that attempt so treatment with ZYBAN should probably be discontinued and the treatment plan reassessed. The goal of therapy with ZYBAN is complete abstinence.

Discuss discontinuing treatment with ZYBAN after 12 weeks if the patient feels ready but consider whether the patient may benefit from ongoing treatment. Patients who successfully quit after 12 weeks of treatment but do not feel ready to discontinue treatment should be considered for ongoing therapy with ZYBAN; longer treatment should be guided by the relative benefits and risks for individual patients.

It is important that patients continue to receive counseling and support throughout treatment with ZYBAN and for a period of time thereafter.

2.3 Individualization of Therapy

Patients are more likely to quit smoking and remain abstinent if they are seen frequently and receive support from their physicians or other healthcare professionals. It is important to ensure that patients read the instructions provided to them and have their questions answered. Physicians should review the patient’s overall smoking cessation program that includes treatment with ZYBAN. Patients should be advised of the importance of participating in the behavioral interventions, counseling, and/or support services to be used in conjunction with ZYBAN [see Medication Guide].

Patients who fail to quit smoking during an attempt may benefit from interventions to improve their chances for success on subsequent attempts. Patients who are unsuccessful should be evaluated to determine why they failed. A new quit attempt should be encouraged when factors that contributed to failure can be eliminated or reduced, and conditions are more favorable.

2.4 Maintenance

Tobacco dependence is a chronic condition. Some patients may need ongoing treatment. Whether to continue treatment with ZYBAN for periods longer than 12 weeks for smoking cessation must be determined for individual patients.

2.5 Combination Treatment with ZYBAN and a Nicotine Transdermal System (NTS)

Combination treatment with ZYBAN and NTS may be prescribed for smoking cessation. The prescriber should review the complete prescribing information for both ZYBAN and NTS before using combination treatment [see Clinical Studies (14)]. Monitoring for treatment‑emergent hypertension in patients treated with the combination of ZYBAN and NTS is recommended.

2.6 Dose Adjustment in Patients with Hepatic Impairment

In patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score: 7 to 15), the maximum dose should not exceed 150 mg every other day. In patients with mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score: 5 to 6), consider reducing the dose and/or frequency of dosing [see Use in Specific Populations (8.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.7 Dose Adjustment in Patients with Renal Impairment

Consider reducing the dose and/or frequency of ZYBAN in patients with renal impairment (Glomerular Filtration Rate less than 90 mL per min) [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.8 Use of ZYBAN with Reversible MAOIs Such as Linezolid or Methylene Blue

Do not start ZYBAN in a patient who is being treated with a reversible MAOI such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. Drug interactions can increase the risk of hypertensive reactions [see Contraindications (4), Drug Interactions (7.6)].

In some cases, a patient already receiving therapy with ZYBAN may require urgent treatment with linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. If acceptable alternatives to linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are not available and the potential benefits of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue treatment are judged to outweigh the risks of hypertensive reactions in a particular patient, ZYBAN should be stopped promptly, and linezolid or intravenous methylene blue can be administered. The patient should be monitored for 2 weeks or until 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue, whichever comes first. Therapy with ZYBAN may be resumed 24 hours after the last dose of linezolid or intravenous methylene blue.

The risk of administering methylene blue by non-intravenous routes (such as oral tablets or by local injection) or in intravenous doses much lower than 1 mg per kg with ZYBAN is unclear. The clinician should, nevertheless, be aware of the possibility of a drug interaction with such use [see Contraindications (4), Drug Interactions (7.6)].

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

150 mg – purple, round, biconvex, film‑coated, sustained-release tablets printed with “ZYBAN 150”.

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

- ZYBAN is contraindicated in patients with a seizure disorder.

- ZYBAN is contraindicated in patients with a current or prior diagnosis of bulimia or anorexia nervosa as a higher incidence of seizures was observed in such patients treated with the immediate‑release formulation of bupropion [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

- ZYBAN is contraindicated in patients undergoing abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and antiepileptic drugs [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Drug Interactions (7.3)].

- The use of MAOIs (intended to treat psychiatric disorders) concomitantly with ZYBAN or within 14 days of discontinuing treatment with ZYBAN is contraindicated. There is an increased risk of hypertensive reactions when ZYBAN is used concomitantly with MAOIs. The use of ZYBAN within 14 days of discontinuing treatment with an MAOI is also contraindicated. Starting ZYBAN in a patient treated with reversible MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue is contraindicated [see Dosage and Administration (2.8), Warnings and Precautions (5.4), Drug Interactions (7.6)].

- ZYBAN is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to bupropion or other ingredients of ZYBAN. Anaphylactoid/anaphylactic reactions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

Although ZYBAN is not indicated for treatment of depression, it contains the same active ingredient as the antidepressant medications WELLBUTRIN, WELLBUTRIN SR, and WELLBUTRIN XL. Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term trials.

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long-standing concern that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment.

Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] and others) show that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18 to 24) with MDD and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term clinical trials did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared with placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared with placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo‑controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short‑term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4,400 subjects. The pooled analyses of placebo‑controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short‑term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 subjects. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger subjects for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk differences (drug vs. placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1,000 subjects treated) are provided in Table 1.

|

Age Range |

Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1,000 Subjects Treated |

|

Increases Compared with Placebo |

|

|

<18 |

14 additional cases |

|

18-24 |

5 additional cases |

|

Decreases Compared with Placebo |

|

|

25-64 |

1 fewer case |

|

≥65 |

6 fewer cases |

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases [see Boxed Warning].

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient’s presenting symptoms.

Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for MDD or other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to healthcare providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers. Prescriptions for ZYBAN should be written for the smallest quantity of tablets consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

5.2 Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events and Suicide Risk in Smoking Cessation Treatment

Serious neuropsychiatric adverse events have been reported in patients taking ZYBAN for smoking cessation. These postmarketing reports have included changes in mood (including depression and mania), psychosis, hallucinations, paranoia, delusions, homicidal ideation, aggression, hostility, agitation, anxiety, and panic, as well as suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)]. Some patients who stopped smoking may have been experiencing symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, including depressed mood. Depression, rarely including suicidal ideation, has been reported in smokers undergoing a smoking cessation attempt without medication. However, some of these adverse events occurred in patients taking ZYBAN who continued to smoke.

Neuropsychiatric adverse events occurred in patients without and with pre-existing psychiatric disease; some patients experienced worsening of their psychiatric illness. Observe patients for the occurrence of neuropsychiatric adverse events. Advise patients and caregivers that the patient should stop taking ZYBAN and contact a healthcare provider immediately if agitation, depressed mood, or changes in behavior or thinking that are not typical for the patient are observed, or if the patient develops suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior. The healthcare provider should evaluate the severity of the adverse events and the extent to which the patient is benefiting from treatment, and consider options including continued treatment under closer monitoring or discontinuing treatment. In many postmarketing cases, resolution of symptoms after discontinuation of ZYBAN was reported. However, the symptoms persisted in some cases; therefore, ongoing monitoring and supportive care should be provided until symptoms resolve.

The neuropsychiatric safety of ZYBAN was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled study that included patients without a history of psychiatric disorder (non-psychiatric cohort, n = 3,912) and patients with a history of psychiatric disorder (psychiatric cohort n = 4,003). In the non-psychiatric cohort, ZYBAN was not associated with an increase composite of the following neuropsychiatric (NPS) adverse events: severe events of anxiety, depression, feeling abnormal, or hostility, and moderate or severe events of agitation, aggression, delusions, hallucinations, homicidal ideation, mania, panic, and irritability. In the psychiatric cohort, there were more events reported in each treatment group compared with the non-psychiatric cohort and the incidence of events in the composite endpoint was higher for ZYBAN compared with placebo: Risk Difference (95% CI) vs. placebo was 2.2% (-0.5, 4.9) for ZYBAN.

In the non-psychiatric cohort, neuropsychiatric adverse events of a serious nature were reported in 0.5% of patients treated with ZYBAN and 0.4% of placebo-treated patients. In the psychiatric cohort, neuropsychiatric events of a serious nature were reported in 0.8% of patients treated with ZYBAN, all involving psychiatric hospitalization. In placebo-treated patients, serious neuropsychiatric events occurred in 0.6%, with 0.2% requiring psychiatric hospitalization [see Clinical Studies (14)].

5.3 Seizure

ZYBAN can cause seizure. The risk of seizure is dose-related. The dose of ZYBAN should not exceed 300 mg per day [see Dosage and Administration (2.1)]. Discontinue ZYBAN and do not restart treatment if the patient experiences a seizure.

The risk of seizures is also related to patient factors, clinical situations, and concomitant medications that lower the seizure threshold. Consider these risks before initiating treatment with ZYBAN. ZYBAN is contraindicated in patients with a seizure disorder, current or prior diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia, or undergoing abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and antiepileptic drugs [see Contraindications (4), Drug Interactions (7.3)]. The following conditions can also increase the risk of seizure: severe head injury; arteriovenous malformation; CNS tumor or CNS infection; severe stroke; concomitant use of other medications that lower the seizure threshold (e.g., other bupropion products, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, theophylline, and systemic corticosteroids), metabolic disorders (e.g., hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, severe hepatic impairment, and hypoxia), use of illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine), or abuse or misuse of prescription drugs such as CNS stimulants. Additional predisposing conditions include diabetes mellitus treated with oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin; use of anorectic drugs; and excessive use of alcohol, benzodiazepines, sedative/hypnotics, or opiates.

Incidence of Seizure with Bupropion Use

Doses for smoking cessation should not exceed 300 mg per day. The seizure rate associated with doses of sustained‑release bupropion in depressed patients up to 300 mg per day is approximately 0.1% (1/1,000) and increases to approximately 0.4% (4/1000) at doses up to 400 mg per day.

The risk of seizure can be reduced if the dose of ZYBAN for smoking cessation does not exceed 300 mg per day, given as 150 mg twice daily, and titration rate is gradual.

5.4 Hypertension

Treatment with ZYBAN can result in elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Assess blood pressure before initiating treatment with ZYBAN, and monitor periodically during treatment. The risk of hypertension is increased if ZYBAN is used concomitantly with MAOIs or other drugs that increase dopaminergic or noradrenergic activity [see Contraindications (4)].

Data from a comparative trial of ZYBAN, NTS, the combination of ZYBAN plus NTS, and placebo as an aid to smoking cessation suggest a higher incidence of treatment-emergent hypertension in patients treated with the combination of ZYBAN and NTS. In this trial, 6.1% of subjects treated with the combination of ZYBAN and NTS had treatment‑emergent hypertension compared with 2.5%, 1.6%, and 3.1% of subjects treated with ZYBAN, NTS, and placebo, respectively. The majority of these subjects had evidence of pre-existing hypertension. Three subjects (1.2%) treated with the combination of ZYBAN and NTS and 1 subject (0.4%) treated with NTS had study medication discontinued due to hypertension compared with none of the subjects treated with ZYBAN or placebo. Monitoring of blood pressure is recommended in patients who receive the combination of bupropion and nicotine replacement.

In a clinical trial of bupropion immediate-release in MDD subjects with stable congestive heart failure (N = 36), bupropion was associated with an exacerbation of pre-existing hypertension in 2 subjects, leading to discontinuation of bupropion treatment. There are no controlled trials assessing the safety of bupropion in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable cardiac disease.

5.5 Activation of Mania/Hypomania

Antidepressant treatment can precipitate a manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode. The risk appears to be increased in patients with bipolar disorder or who have risk factors for bipolar disorder. There were no reports of activation of psychosis or mania in premarketing clinical trials with ZYBAN conducted in nondepressed smokers. However, events of this nature were seen in patients with pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses in a smoking cessation trial [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. Bupropion is not approved for use in treating bipolar depression.

5.6 Psychosis and Other Neuropsychiatric Reactions

Depressed patients treated with bupropion in depression trials have had a variety of neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, psychosis, concentration disturbance, paranoia, and confusion. Some of these patients had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. In some cases, these symptoms abated upon dose reduction and/or withdrawal of treatment. Instruct patients to contact a healthcare professional if such reactions occur.

In premarketing clinical trials with ZYBAN conducted in non-depressed smokers, the incidence of neuropsychiatric side effects was generally comparable to placebo. However, in the postmarketing experience, patients taking ZYBAN to quit smoking have reported similar types of neuropsychiatric symptoms to those reported by patients in the clinical trials of bupropion for depression [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

5.7 Angle-Closure Glaucoma

The pupillary dilation that occurs following use of many antidepressant drugs including bupropion may trigger an angle-closure attack in a patient with anatomically narrow angles who does not have a patent iridectomy.

5.8 Hypersensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactoid/anaphylactic reactions have occurred during clinical trials with bupropion. Reactions have been characterized by pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, and dyspnea requiring medical treatment. In addition, there have been rare, spontaneous postmarketing reports of erythema multiforme, Stevens‑Johnson syndrome, and anaphylactic shock associated with bupropion. Instruct patients to discontinue ZYBAN and consult a healthcare provider if they develop an allergic or anaphylactoid/anaphylactic reaction (e.g., skin rash, pruritus, hives, chest pain, edema, and shortness of breath) during treatment.

There are reports of arthralgia, myalgia, fever with rash and other serum sickness-like symptoms suggestive of delayed hypersensitivity.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions are discussed in greater detail in other sections of the labeling:

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents and young adults [see Boxed Warning, Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Neuropsychiatric adverse events and suicide risk in smoking cessation treatment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Seizure [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Hypertension [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Activation of mania or hypomania [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Psychosis and other neuropsychiatric reactions [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Angle-closure glaucoma [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Hypersensitivity reactions [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared with rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in clinical practice.

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation of Treatment

Adverse reactions were sufficiently troublesome to cause discontinuation of treatment in 8% of the 706 subjects treated with ZYBAN and 5% of the 313 patients treated with placebo. The more common events leading to discontinuation of treatment with ZYBAN included nervous system disturbances (3.4%), primarily tremors, and skin disorders (2.4%), primarily rashes.

Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions

The most commonly observed adverse reactions consistently associated with the use of ZYBAN were dry mouth and insomnia. The incidence of dry mouth and insomnia may be related to the dose of ZYBAN. The occurrence of these adverse reactions may be minimized by reducing the dose of ZYBAN. In addition, insomnia may be minimized by avoiding bedtime doses.

Adverse reactions reported in the dose-response and comparator trials are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Reported adverse reactions were classified using a COSTART‑based dictionary.

|

Adverse Reaction |

ZYBAN 100 to 300 mg/day (n = 461) % |

Placebo (n = 150) % |

|

Body (General) | ||

|

Neck pain |

2 |

<1 |

|

Allergic reaction |

1 |

0 |

|

Cardiovascular | ||

|

Hot flashes |

1 |

0 |

|

Hypertension |

1 |

<1 |

|

Digestive | ||

|

Dry mouth |

11 |

5 |

|

Increased appetite |

2 |

<1 |

|

Anorexia |

1 |

<1 |

|

Musculoskeletal | ||

|

Arthralgia |

4 |

3 |

|

Myalgia |

2 |

1 |

|

Nervous system | ||

|

Insomnia |

31 |

21 |

|

Dizziness |

8 |

7 |

|

Tremor |

2 |

1 |

|

Somnolence |

2 |

1 |

|

Thinking abnormality |

1 |

0 |

|

Respiratory | ||

|

Bronchitis |

2 |

0 |

|

Skin | ||

|

Pruritus |

3 |

<1 |

|

Rash |

3 |

<1 |

|

Dry skin |

2 |

0 |

|

Urticaria |

1 |

0 |

|

Special senses | ||

|

Taste perversion |

2 |

<1 |

|

Adverse Experience (Costart Term) |

ZYBAN 300 mg/day (n = 243) % |

Nicotine Transdermal System (NTS) 21 mg/day (n = 243) % |

ZYBAN and NTS (n = 244) % |

Placebo (n = 159) % |

|

Body | ||||

|

Abdominal pain |

3 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

|

Accidental injury |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Chest pain |

<1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

Neck pain |

2 |

1 |

<1 |

0 |

|

Facial edema |

<1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Cardiovascular | ||||

|

Hypertension |

1 |

<1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Palpitations |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Digestive | ||||

|

Nausea |

9 |

7 |

11 |

4 |

|

Dry mouth |

10 |

4 |

9 |

4 |

|

Constipation |

8 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

|

Diarrhea |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Anorexia |

3 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

|

Mouth ulcer |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Thirst |

<1 |

<1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Musculoskeletal | ||||

|

Myalgia |

4 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

|

Arthralgia |

5 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

|

Nervous system | ||||

|

Insomnia |

40 |

28 |

45 |

18 |

|

Dream abnormality |

5 |

18 |

13 |

3 |

|

Anxiety |

8 |

6 |

9 |

6 |

|

Disturbed concentration |

9 |

3 |

9 |

4 |

|

Dizziness |

10 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

|

Nervousness |

4 |

<1 |

2 |

2 |

|

Tremor |

1 |

<1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Dysphoria |

<1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Respiratory | ||||

|

Rhinitis |

12 |

11 |

9 |

8 |

|

Increased cough |

3 |

5 |

<1 |

1 |

|

Pharyngitis |

3 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Sinusitis |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

Dyspnea |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

|

Epistaxis |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Skin | ||||

|

Application site reactiona |

11 |

17 |

15 |

7 |

|

Rash |

4 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

|

Pruritus |

3 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

|

Urticaria |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Special Senses | ||||

|

Taste perversion |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

|

Tinnitus |

1 |

0 |

<1 |

0 |

aSubjects randomized to ZYBAN or placebo received placebo patches.

Adverse reactions in a 1-year maintenance trial and a 12-week COPD trial with ZYBAN were quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those observed in the dose‑response and comparator trials.

In the trial of patients without or with a history of psychiatric disorder, the most common adverse events in subjects treated with ZYBAN were broadly similar to those observed in premarketing studies. Adverse events reported in >10% of subjects treated with ZYBAN in the entire study population were nausea, insomnia, and anxiety disorders. Additionally, the following psychiatric adverse events were reported in >2% of patients in either treatment group (ZYBAN vs. placebo) by cohort. For the non-psychiatric cohort, these adverse events were anxiety, nervousness, abnormal dreams, and insomnia. For the psychiatric cohort, these adverse events were agitation, anxiety, panic, abnormal dreams, insomnia, and crying.

Other Adverse Reactions Observed during the Clinical Development of Bupropion

In addition to the adverse reactions noted above, the following adverse reactions have been reported in clinical trials with the sustained‑release formulation of bupropion in depressed subjects and in nondepressed smokers, as well as in clinical trials with the immediate‑release formulation of bupropion.

Adverse reaction frequencies represent the proportion of subjects who experienced a treatment‑emergent adverse reaction on at least one occasion in placebo‑controlled trials for depression (n = 987) or smoking cessation (n = 1,013), or subjects who experienced an adverse reaction requiring discontinuation of treatment in an open‑label surveillance trial with bupropion sustained‑release tablets (n = 3,100). All treatment‑emergent adverse reactions are included except those listed in Tables 2 and 3, those listed in other safety‑related sections of the prescribing information, those subsumed under COSTART terms that are either overly general or excessively specific so as to be uninformative, those not reasonably associated with the use of the drug, and those that were not serious and occurred in fewer than 2 subjects.

Adverse reactions are further categorized by body system and listed in order of decreasing frequency according to the following definitions of frequency: Frequent adverse reactions are defined as those occurring in at least 1/100 subjects. Infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1,000 subjects, while rare events are those occurring in less than 1/1,000 subjects.

Body (General): Frequent were asthenia, fever, and headache. Infrequent were chills, inguinal hernia, and photosensitivity. Rare was malaise.

Cardiovascular: Infrequent were flushing, migraine, postural hypotension, stroke, tachycardia, and vasodilation. Rare was syncope.

Digestive: Frequent were dyspepsia and vomiting. Infrequent were abnormal liver function, bruxism, dysphagia, gastric reflux, gingivitis, jaundice, and stomatitis.

Hemic and Lymphatic: Infrequent was ecchymosis.

Metabolic and Nutritional: Infrequent were edema and peripheral edema.

Musculoskeletal: Infrequent were leg cramps and twitching.

Nervous System: Frequent were agitation, depression, and irritability. Infrequent were abnormal coordination, CNS stimulation, confusion, decreased libido, decreased memory, depersonalization, emotional lability, hostility, hyperkinesia, hypertonia, hypesthesia, paresthesia, suicidal ideation, and vertigo. Rare were amnesia, ataxia, derealization, and hypomania.

Respiratory: Rare was bronchospasm.

Skin: Frequent was sweating.

Special Senses: Frequent was blurred vision or diplopia. Infrequent were accommodation abnormality and dry eye.

Urogenital: Frequent was urinary frequency. Infrequent were impotence, polyuria, and urinary urgency.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of ZYBAN and are not described elsewhere in the label. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a relationship to drug exposure.

Body (General)

Arthralgia, myalgia, and fever with rash and other symptoms suggestive of delayed hypersensitivity. These symptoms may resemble serum sickness [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular disorder, complete AV block, extrasystoles, hypotension, myocardial infarction, phlebitis, and pulmonary embolism.

Digestive

Colitis, esophagitis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gum hemorrhage, hepatitis, increased salivation, intestinal perforation, liver damage, pancreatitis, stomach ulcer, and stool abnormality.

Endocrine

Hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Hemic and Lymphatic

Anemia, leukocytosis, leukopenia, lymphadenopathy, pancytopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Altered PT and/or INR, infrequently associated with hemorrhagic or thrombotic complications, were observed when bupropion was coadministered with warfarin.

Metabolic and Nutritional

Glycosuria.

Musculoskeletal

Arthritis and muscle rigidity/fever/rhabdomyolysis, and muscle weakness.

Nervous System

Abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG), aggression, akinesia, aphasia, coma, completed suicide, delirium, delusions, dysarthria, euphoria, extrapyramidal syndrome (dyskinesia, dystonia, hypokinesia, parkinsonism), hallucinations, increased libido, manic reaction, neuralgia, neuropathy, paranoid ideation, restlessness, suicide attempt, and unmasking tardive dyskinesia.

Respiratory

Pneumonia.

Skin

Alopecia, angioedema, exfoliative dermatitis, hirsutism, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Special Senses

Deafness, increased intraocular pressure, and mydriasis.

Urogenital

Abnormal ejaculation, cystitis, dyspareunia, dysuria, gynecomastia, menopause, painful erection, prostate disorder, salpingitis, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, urinary tract disorder, and vaginitis.

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Potential for Other Drugs to Affect ZYBAN

Bupropion is primarily metabolized to hydroxybupropion by CYP2B6. Therefore, the potential exists for drug interactions between ZYBAN and drugs that are inhibitors or inducers of CYP2B6.

Inhibitors of CYP2B6

Ticlopidine and Clopidogrel: Concomitant treatment with these drugs can increase bupropion exposure but decrease hydroxybupropion exposure. Based on clinical response, dosage adjustment of ZYBAN may be necessary when coadministered with CYP2B6 inhibitors (e.g., ticlopidine or clopidogrel) [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Inducers of CYP2B6

Ritonavir, Lopinavir, and Efavirenz: Concomitant treatment with these drugs can decrease bupropion and hydroxybupropion exposure. Dosage increase of ZYBAN may be necessary when coadministered with ritonavir, lopinavir, or efavirenz [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)] but should not exceed the maximum recommended dose.

Carbamazepine, Phenobarbital, Phenytoin: While not systematically studied, these drugs may induce the metabolism of bupropion and may decrease bupropion exposure [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. If bupropion is used concomitantly with a CYP inducer, it may be necessary to increase the dose of bupropion, but the maximum recommended dose should not be exceeded.

7.2 Potential for ZYBAN to Affect Other Drugs

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6

Bupropion and its metabolites (erythrohydrobupropion, threohydrobupropion, hydroxybupropion) are CYP2D6 inhibitors. Therefore, coadministration of ZYBAN with drugs that are metabolized by CYP2D6 can increase the exposures of drugs that are substrates of CYP2D6. Such drugs include certain antidepressants (e.g., venlafaxine, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline), antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, risperidone, thioridazine), beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol), and Type 1C antiarrhythmics (e.g., propafenone and flecainide). When used concomitantly with ZYBAN, it may be necessary to decrease the dose of these CYP2D6 substrates, particularly for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index.

Drugs that require metabolic activation by CYP2D6 to be effective (e.g., tamoxifen) theoretically could have reduced efficacy when administered concomitantly with inhibitors of CYP2D6 such as bupropion. Patients treated concomitantly with ZYBAN and such drugs may require increased doses of the drug [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Digoxin

Coadministration of ZYBAN with digoxin may decrease plasma digoxin levels. Monitor plasma digoxin levels in patients treated concomitantly with ZYBAN and digoxin [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.3 Drugs that Lower Seizure Threshold

Use extreme caution when coadministering ZYBAN with other drugs that lower seizure threshold (e.g., other bupropion products, antipsychotics, antidepressants, theophylline, or systemic corticosteroids). Use low initial doses and increase the dose gradually [see Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

7.4 Dopaminergic Drugs (Levodopa and Amantadine)

Bupropion, levodopa, and amantadine have dopamine agonist effects. CNS toxicity has been reported when bupropion was coadministered with levodopa or amantadine. Adverse reactions have included restlessness, agitation, tremor, ataxia, gait disturbance, vertigo, and dizziness. It is presumed that the toxicity results from cumulative dopamine agonist effects. Use caution when administering ZYBAN concomitantly with these drugs.

7.5 Use with Alcohol

In postmarketing experience, there have been rare reports of adverse neuropsychiatric events or reduced alcohol tolerance in patients who were drinking alcohol during treatment with ZYBAN. The consumption of alcohol during treatment with ZYBAN should be minimized or avoided.

7.6 MAO Inhibitors

Bupropion inhibits the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. Concomitant use of MAOIs and bupropion is contraindicated because there is an increased risk of hypertensive reactions if bupropion is used concomitantly with MAOIs. Studies in animals demonstrate that the acute toxicity of bupropion is enhanced by the MAO inhibitor phenelzine. At least 14 days should elapse between discontinuation of an MAOI and initiation of treatment with ZYBAN. Conversely, at least 14 days should be allowed after stopping ZYBAN before starting an MAOI intended to treat psychiatric disorders [see Dosage and Administration (2.8), Contraindications (4)].

7.7 Smoking Cessation

Physiological changes resulting from smoking cessation, with or without treatment with ZYBAN, may alter the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of certain drugs (e.g., theophylline, warfarin, insulin) for which dosage adjustment may be necessary.

7.8 Drug-Laboratory Test Interactions

False-positive urine immunoassay screening tests for amphetamines have been reported in patients taking bupropion. This is due to lack of specificity of some screening tests. False-positive test results may result even following discontinuation of bupropion therapy. Confirmatory tests, such as gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, will distinguish bupropion from amphetamines.

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C.

Risk Summary

Data from epidemiological studies of pregnant women exposed to bupropion in the first trimester indicate no increased risk of congenital malformations overall. All pregnancies, regardless of drug exposure, have a background rate of 2% to 4% for major malformations, and 15% to 20% for pregnancy loss. No clear evidence of teratogenic activity was found in reproductive developmental studies conducted in rats and rabbits; however, in rabbits, slightly increased incidences of fetal malformations and skeletal variations were observed at doses approximately 2 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) and greater and decreased fetal weights were seen at doses three times the MRHD and greater. ZYBAN should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Clinical Considerations

Pregnant smokers should be encouraged to attempt cessation using educational and behavioral interventions before pharmacological approaches are used.

Data

Human Data: Data from the international bupropion Pregnancy Registry (675 first trimester exposures) and a retrospective cohort study using the United Healthcare database (1,213 first trimester exposures) did not show an increased risk for malformations overall.

No increased risk for cardiovascular malformations overall has been observed after bupropion exposure during the first trimester. The prospectively observed rate of cardiovascular malformations in pregnancies with exposure to bupropion in the first trimester from the international Pregnancy Registry was 1.3% (9 cardiovascular malformations/675 first trimester maternal bupropion exposures), which is similar to the background rate of cardiovascular malformations (approximately 1%). Data from the United Healthcare database and a case-control study (6,853 infants with cardiovascular malformations and 5,763 with non-cardiovascular malformations) from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) did not show an increased risk for cardiovascular malformations overall after bupropion exposure during the first trimester.

Study findings on bupropion exposure during the first trimester and risk for left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) are inconsistent and do not allow conclusions regarding a possible association. The United Healthcare database lacked sufficient power to evaluate this association; the NBDPS found increased risk for LVOTO (n = 10; adjusted OR = 2.6; 95% CI: 1.2, 5.7), and the Slone Epidemiology case control study did not find increased risk for LVOTO.

Study findings on bupropion exposure during the first trimester and risk for ventricular septal defect (VSD) are inconsistent and do not allow conclusions regarding a possible association. The Slone Epidemiology Study found an increased risk for VSD following first trimester maternal bupropion exposure (n = 17; adjusted OR = 2.5; 95% CI: 1.3, 5.0) but did not find increased risk for any other cardiovascular malformations studied (including LVOTO as above). The NBDPS and United Healthcare database study did not find an association between first trimester maternal bupropion exposure and VSD.

For the findings of LVOTO and VSD, the studies were limited by the small number of exposed cases, inconsistent findings among studies, and the potential for chance findings from multiple comparisons in case control studies.

Animal Data: In studies conducted in rats and rabbits, bupropion was administered orally during the period of organogenesis at doses of up to 450 and 150 mg per kg per day, respectively (approximately 15 and 10 times the MRHD respectively, on a mg per m2 basis). No clear evidence of teratogenic activity was found in either species; however, in rabbits, slightly increased incidences of fetal malformations and skeletal variations were observed at the lowest dose tested (25 mg per kg per day, approximately 2 times the MRHD on a mg per m2 basis) and greater. Decreased fetal weights were observed at 50 mg per kg and greater.

When rats were administered bupropion at oral doses of up to 300 mg per kg per day (approximately 10 times the MRHD on a mg per m2 basis) prior to mating and throughout pregnancy and lactation, there were no apparent adverse effects on offspring development.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

Bupropion and its metabolites are present in human milk. In a lactation study of 10 women, levels of orally dosed bupropion and its active metabolites were measured in expressed milk. The average daily infant exposure (assuming 150 mL per kg daily consumption) to bupropion and its active metabolites was 2% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose. Exercise caution when ZYBAN is administered to a nursing woman.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in the pediatric population have not been established [see Boxed Warning, Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

8.5 Geriatric Use

Of the approximately 6,000 subjects who participated in clinical trials with bupropion sustained‑release tablets (depression and smoking cessation trials), 275 were aged ≥65 years and 47 were aged ≥75 years. In addition, several hundred subjects aged ≥65 years participated in clinical trials using the immediate-release formulation of bupropion (depression trials). No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects. Reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out.

Bupropion is extensively metabolized in the liver to active metabolites, which are further metabolized and excreted by the kidneys. The risk of adverse reactions may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, it may be necessary to consider this factor in dose selection; it may be useful to monitor renal function [see Dosage and Administration (2.7), Use in Specific Populations (8.6), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.6 Renal Impairment

Consider a reduced dose and/or dosing frequency of ZYBAN in patients with renal impairment (Glomerular Filtration Rate: less than 90 mL per min). Bupropion and its metabolites are cleared renally and may accumulate in such patients to a greater extent than usual. Monitor closely for adverse reactions that could indicate high bupropion or metabolite exposures [see Dosage and Administration (2.7), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.7 Hepatic Impairment

In patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score: 7 to 15), the maximum dose of ZYBAN is 150 mg every other day. In patients with mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score: 5 to 6), consider reducing the dose and/or frequency of dosing [see Dosage and Administration (2.6), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

Humans

Controlled clinical trials conducted in normal volunteers, in subjects with a history of multiple drug abuse, and in depressed subjects showed some increase in motor activity and agitation/excitement, often typical of central stimulant activity.

In a population of individuals experienced with drugs of abuse, a single oral dose of 400 mg of bupropion produced mild amphetamine‑like activity as compared with placebo on the Morphine‑Benzedrine Subscale of the Addiction Research Center Inventories (ARCI) and a score greater than placebo but less than 15 mg of the Schedule II stimulant dextroamphetamine on the Liking Scale of the ARCI. These scales measure general feelings of euphoria and drug liking which are often associated with abuse potential.

Findings in clinical trials, however, are not known to reliably predict the abuse potential of drugs. Nonetheless, evidence from single‑dose trials does suggest that the recommended daily dosage of bupropion when administered orally in divided doses is not likely to be significantly reinforcing to amphetamine or CNS stimulant abusers. However, higher doses (which could not be tested because of the risk of seizure) might be modestly attractive to those who abuse CNS stimulant drugs.

ZYBAN is intended for oral use only. The inhalation of crushed tablets or injection of dissolved bupropion has been reported. Seizures and/or cases of death have been reported when bupropion has been administered intranasally or by parenteral injection.

Animals

Studies in rodents and primates demonstrated that bupropion exhibits some pharmacologic actions common to psychostimulants. In rodents, it has been shown to increase locomotor activity, elicit a mild stereotyped behavior response, and increase rates of responding in several schedule‑controlled behavior paradigms. In primate models assessing the positive reinforcing effects of psychoactive drugs, bupropion was self‑administered intravenously. In rats, bupropion produced amphetamine-like and cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects in drug discrimination paradigms used to characterize the subjective effects of psychoactive drugs.

The possibility that bupropion may induce dependence should be kept in mind when evaluating the desirability of including the drug in smoking cessation programs of individual patients.

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Overdose Experience

Overdoses of up to 30 grams or more of bupropion have been reported. Seizure was reported in approximately one-third of all cases. Other serious reactions reported with overdoses of bupropion alone included hallucinations, loss of consciousness, sinus tachycardia, and ECG changes such as conduction disturbances (including QRS prolongation) or arrhythmias. Fever, muscle rigidity, rhabdomyolysis, hypotension, stupor, coma, and respiratory failure have been reported mainly when bupropion was part of multiple drug overdoses.

Although most patients recovered without sequelae, deaths associated with overdoses of bupropion alone have been reported in patients ingesting large doses of the drug. Multiple uncontrolled seizures, bradycardia, cardiac failure, and cardiac arrest prior to death were reported in these patients.

10.2 Overdosage Management

Consult a Certified Poison Control Center for up–to-date guidance and advice. Telephone numbers for certified poison control centers are listed in the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR). Call 1-800-222-1222 or refer to www.poison.org.

There are no known antidotes for bupropion. In case of an overdose, provide supportive care, including close medical supervision and monitoring. Consider the possibility of multiple drug overdose. Ensure an adequate airway, oxygenation, and ventilation. Monitor cardiac rhythm and vital signs. Induction of emesis is not recommended.

11 DESCRIPTION

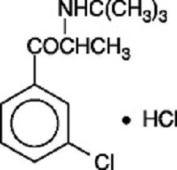

ZYBAN (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained‑release tablets are a non‑nicotine aid to smoking cessation. ZYBAN is chemically unrelated to nicotine or other agents currently used in the treatment of nicotine addiction. Initially developed and marketed as an antidepressant (WELLBUTRIN [bupropion hydrochloride] tablets and WELLBUTRIN SR [bupropion hydrochloride] sustained‑release tablets), ZYBAN is also chemically unrelated to tricyclic, tetracyclic, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor, or other known antidepressant agents. Its structure closely resembles that of diethylpropion; it is related to phenylethylamines. It is designated as (±)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)-2-[(1,1-dimethylethyl)amino]-1-propanone hydrochloride. The molecular weight is 276.2. The molecular formula is C13H18ClNOHCl. Bupropion hydrochloride powder is white, crystalline, and highly soluble in water. It has a bitter taste and produces the sensation of local anesthesia on the oral mucosa. The structural formula is:

ZYBAN is supplied for oral administration as 150‑mg (purple), film‑coated, sustained‑release tablets. Each tablet contains the labeled amount of bupropion hydrochloride and the inactive ingredients carnauba wax, cysteine hydrochloride, hypromellose, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate 80, and titanium dioxide and is printed with edible black ink. In addition, the 150‑mg tablet contains FD&C Blue No. 2 Lake and FD& C Red No. 40 Lake.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The exact mechanism by which ZYBAN enhances the ability of patients to abstain from smoking is not known but is presumed to be related to noradrenergic and/or dopaminergic mechanisms. Bupropion is a relatively weak inhibitor of the neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, and does not inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. Bupropion does not inhibit monoamine oxidase.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Bupropion is a racemic mixture. The pharmacological activity and pharmacokinetics of the individual enantiomers have not been studied. The mean elimination half-life (±SD) of bupropion after chronic dosing is 21 (±9) hours, and steady-state plasma concentrations of bupropion are reached within 8 days.

Absorption

The absolute bioavailability of ZYBAN in humans has not been determined because an intravenous formulation for human use is not available. However, it appears likely that only a small proportion of any orally administered dose reaches the systemic circulation intact. In rat and dog studies, the bioavailability of bupropion ranged from 5% to 20%.

In humans, following oral administration of ZYBAN, peak plasma concentration (Cmax) of bupropion is usually achieved within 3 hours.

ZYBAN can be taken with or without food. Bupropion Cmax and AUC were increased by 11% to 35%, and 16% to 19%, respectively, when ZYBAN was administered with food to healthy volunteers in three trials. The food effect is not considered clinically significant.

Distribution

In vitro tests show that bupropion is 84% bound to human plasma proteins at concentrations up to 200 mcg per mL. The extent of protein binding of the hydroxybupropion metabolite is similar to that for bupropion; whereas, the extent of protein binding of the threohydrobupropion metabolite is about half that seen with bupropion.

Metabolism

Bupropion is extensively metabolized in humans. Three metabolites are active: hydroxybupropion, which is formed via hydroxylation of the tert‑butyl group of bupropion, and the amino-alcohol isomers, threohydrobupropion and erythrohydrobupropion, which are formed via reduction of the carbonyl group. In vitro findings suggest that CYP2B6 is the principal isoenzyme involved in the formation of hydroxybupropion, while cytochrome P450 enzymes are not involved in the formation of threohydrobupropion. Oxidation of the bupropion side chain results in the formation of a glycine conjugate of meta‑chlorobenzoic acid, which is then excreted as the major urinary metabolite. The potency and toxicity of the metabolites relative to bupropion have not been fully characterized. However, it has been demonstrated in an antidepressant screening test in mice that hydroxybupropion is one-half as potent as bupropion, while threohydrobupropion and erythrohydrobupropion are 5‑fold less potent than bupropion. This may be of clinical importance, because the plasma concentrations of the metabolites are as high as or higher than those of bupropion.

Following a single-dose administration of ZYBAN in humans, Cmax of hydroxybupropion occurs approximately 6 hours post-dose and is approximately 10 times the peak level of the parent drug at steady state. The elimination half-life of hydroxybupropion is approximately 20 (±5) hours and its AUC at steady state is about 17 times that of bupropion. The times to peak concentrations for the erythrohydrobupropion and threohydrobupropion metabolites are similar to that of the hydroxybupropion metabolite. However, their elimination half-lives are longer, 33 (±10) and 37 (±13) hours, respectively, and steady‑state AUCs are 1.5 and 7 times that of bupropion, respectively.

Bupropion and its metabolites exhibit linear kinetics following chronic administration of 300 to 450 mg per day.

Elimination

Following oral administration of 200 mg of 14C‑bupropion in humans, 87% and 10% of the radioactive dose were recovered in the urine and feces, respectively. Only 0.5% of the oral dose was excreted as unchanged bupropion.

Specific Populations

Factors or conditions altering metabolic capacity (e.g., liver disease, congestive heart failure [CHF], age, concomitant medications, etc.) or elimination may be expected to influence the degree and extent of accumulation of the active metabolites of bupropion. The elimination of the major metabolites of bupropion may be affected by reduced renal or hepatic function because they are moderately polar compounds and are likely to undergo further metabolism or conjugation in the liver prior to urinary excretion.

Patients with Renal Impairment: There is limited information on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion in patients with renal impairment. An inter-trial comparison between normal subjects and subjects with end-stage renal failure demonstrated that the parent drug Cmax and AUC values were comparable in the 2 groups, whereas the hydroxybupropion and threohydrobupropion metabolites had a 2.3- and 2.8-fold increase, respectively, in AUC for subjects with end-stage renal failure. A second trial, comparing normal subjects and subjects with moderate‑to‑severe renal impairment (GFR 30.9 ± 10.8 mL per min), showed that after a single 150‑mg dose of sustained-release bupropion, exposure to bupropion was approximately 2-fold higher in subjects with impaired renal function while levels of the hydroxybupropion and threo/erythrohydrobupropion (combined) metabolites were similar in the 2 groups. Bupropion is extensively metabolized in the liver to active metabolites, which are further metabolized and subsequently excreted by the kidneys. The elimination of the major metabolites of bupropion may be reduced by impaired renal function. ZYBAN should be used with caution in patients with renal impairment and a reduced frequency and/or dose should be considered [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Patients with Hepatic Impairment: The effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion was characterized in 2 single-dose trials, one in subjects with alcoholic liver disease and one in subjects with mild-to-severe cirrhosis. The first trial demonstrated that the half‑life of hydroxybupropion was significantly longer in 8 subjects with alcoholic liver disease than in 8 healthy volunteers (32 ± 14 hours versus 21 ± 5 hours, respectively). Although not statistically significant, the AUCs for bupropion and hydroxybupropion were more variable and tended to be greater (by 53% to 57%) in volunteers with alcoholic liver disease. The differences in half‑life for bupropion and the other metabolites in the 2 groups were minimal.

The second trial demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its active metabolites in 9 subjects with mild-to-moderate hepatic cirrhosis compared with 8 healthy volunteers. However, more variability was observed in some of the pharmacokinetic parameters for bupropion (AUC, Cmax, and Tmax) and its active metabolites (t½) in subjects with mild-to-moderate hepatic cirrhosis. In 8 subjects with severe hepatic cirrhosis, significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites were seen (Table 4).

|

Cmax |

AUC |

t½ |

Tmaxa |

|

|

Bupropion |

1.69 |

3.12 |

1.43 |

0.5 h |

|

Hydroxybupropion |

0.31 |

1.28 |

3.88 |

19 h |

|

Threo/erythrohydrobupropion amino alcohol |

0.69 |

2.48 |

1.96 |

20 h |

aDifference.

Smokers: The effects of cigarette smoking on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion were studied in 34 healthy male and female volunteers; 17 were chronic cigarette smokers and 17 were nonsmokers. Following oral administration of a single 150‑mg dose of ZYBAN, there were no statistically significant differences in Cmax, half‑life, Tmax, AUC, or clearance of bupropion or its major metabolites between smokers and nonsmokers.

In a trial comparing the treatment combination of ZYBAN and NTS versus ZYBAN alone, no statistically significant differences were observed between the 2 treatment groups of combination ZYBAN and NTS (n = 197) and ZYBAN alone (n = 193) in the plasma concentrations of bupropion or its active metabolites at Weeks 3 and 6.

Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction: During a chronic dosing trial with bupropion in 14 depressed subjects with left ventricular dysfunction (history of CHF or an enlarged heart on x‑ray), there was no apparent effect on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion or its metabolites, compared with healthy volunteers.

Age: The effects of age on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites have not been fully characterized, but an exploration of steady‑state bupropion concentrations from several depression efficacy trials involving subjects dosed in a range of 300 to 750 mg per day, on a 3-times-daily schedule, revealed no relationship between age (18 to 83 years) and plasma concentration of bupropion. A single‑dose pharmacokinetic trial demonstrated that the disposition of bupropion and its metabolites in elderly subjects was similar to that of younger subjects. These data suggest there is no prominent effect of age on bupropion concentration; however, another single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics trial suggested that the elderly are at increased risk for accumulation of bupropion and its metabolites [see Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

Male and Female Patients: Pooled analysis of bupropion pharmacokinetic data from 90 healthy male and 90 healthy female volunteers revealed no sex‑related differences in the peak plasma concentrations of bupropion. The mean systemic exposure (AUC) was approximately 13% higher in male volunteers compared with female volunteers. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown.

Drug Interaction Studies

Potential for Other Drugs to Affect ZYBAN: In vitro studies indicate that bupropion is primarily metabolized to hydroxybupropion by CYP2B6. Therefore, the potential exists for drug interactions between ZYBAN and drugs that are inhibitors or inducers of CYP2B6. In addition, in vitro studies suggest that paroxetine, sertraline, norfluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and nelfinavir inhibit the hydroxylation of bupropion.

Inhibitors of CYP2B6: Ticlopidine, Clopidogrel: In a trial in healthy male volunteers, clopidogrel 75 mg once daily or ticlopidine 250 mg twice daily increased exposures (Cmax and AUC) of bupropion by 40% and 60% for clopidogrel, and by 38% and 85% for ticlopidine, respectively. The exposures (Cmax and AUC) of hydroxybupropion were decreased 50% and 52%, respectively, by clopidogrel, and 78% and 84%, respectively, by ticlopidine. This effect is thought to be due to the inhibition of the CYP2B6-catalyzed bupropion hydroxylation.

Prasugrel: Prasugrel is a weak inhibitor of CYP2B6. In healthy subjects, prasugrel increased bupropion Cmax and AUC values by 14% and 18%, respectively, and decreased Cmax and AUC values of hydroxybupropion, an active metabolite of bupropion, by 32% and 24%, respectively.

Cimetidine: The threohydrobupropion metabolite of bupropion does not appear to be produced by cytochrome P450 enzymes. The effects of concomitant administration of cimetidine on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its active metabolites were studied in 24 healthy young male volunteers. Following oral administration of bupropion 300 mg with and without cimetidine 800 mg, the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and hydroxybupropion were unaffected. However, there were 16% and 32% increases in the AUC and Cmax, respectively, of the combined moieties of threohydrobupropion and erythrohydrobupropion.

Citalopram: Citalopram did not affect the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its 3 metabolites.

Inducers of CYP2B6: Ritonavir and Lopinavir: In a healthy volunteer trial, ritonavir 100 mg twice daily reduced the AUC and Cmax of bupropion by 22% and 21%, respectively. The exposure of the hydroxybupropion metabolite was decreased by 23%, the threohydrobupropion decreased by 38%, and the erythrohydrobupropion decreased by 48%.

In a second healthy volunteer trial, ritonavir at a dose of 600 mg twice daily decreased the AUC and the Cmax of bupropion by 66% and 62%, respectively. The exposure of the hydroxybupropion metabolite was decreased by 78%, the threohydrobupropion decreased by 50%, and the erythrohydrobupropion decreased by 68%.

In another healthy volunteer trial, lopinavir 400 mg/ritonavir 100 mg twice daily decreased bupropion AUC and Cmax by 57%. The AUC and Cmax of hydroxybupropion were decreased by 50% and 31%, respectively.

Efavirenz: In a trial in healthy volunteers, efavirenz 600 mg once daily for 2 weeks reduced the AUC and Cmax of bupropion by approximately 55% and 34%, respectively. The AUC of hydroxybupropion was unchanged, whereas Cmax of hydroxybupropion was increased by 50%.

Carbamazepine, Phenobarbital, Phenytoin: While not systematically studied, these drugs may induce the metabolism of bupropion.

Potential for ZYBAN to Affect Other Drugs

Animal data indicated that bupropion may be an inducer of drug-metabolizing enzymes in humans. In one trial, following chronic administration of bupropion 100 mg three times daily to 8 healthy male volunteers for 14 days, there was no evidence of induction of its own metabolism. Nevertheless, there may be potential for clinically important alterations of blood levels of co-administered drugs.

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6: In vitro, bupropion and its metabolites (erythrohydrobupropion, threohydrobupropion, hydroxybupropion) are CYP2D6 inhibitors. In a clinical trial of 15 male subjects (ages 19 to 35 years) who were extensive metabolizers of CYP2D6, bupropion 300 mg per day followed by a single dose of 50 mg desipramine increased the Cmax, AUC, and t1/2 of desipramine by an average of approximately 2-, 5- and 2-fold, respectively. The effect was present for at least 7 days after the last dose of bupropion. Concomitant use of bupropion with other drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 has not been formally studied.

Citalopram: Although citalopram is not primarily metabolized by CYP2D6, in one trial bupropion increased the Cmax and AUC of citalopram by 30% and 40%, respectively.

Lamotrigine: Multiple oral doses of bupropion had no statistically significant effects on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine in 12 healthy volunteers.

Digoxin: Literature data showed that digoxin exposure was decreased when a single oral dose of 0.5-mg digoxin was administered 24 hours after a single oral dose of extended-release 150-mg bupropion in healthy volunteers.

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Lifetime carcinogenicity studies were performed in rats and mice at bupropion doses up to 300 and 150 mg per kg per day, respectively. These doses are approximately 10 and 2 times the MRHD, respectively, on a mg per m2 basis. In the rat study there was an increase in nodular proliferative lesions of the liver at doses of 100 to 300 mg per kg per day (approximately 3 to 10 times the MRHD on a mg per m2 basis); lower doses were not tested. The question of whether or not such lesions may be precursors of neoplasms of the liver is currently unresolved. Similar liver lesions were not seen in the mouse study, and no increase in malignant tumors of the liver and other organs was seen in either study.

Bupropion produced a positive response (2 to 3 times control mutation rate) in 2 of 5 strains in the Ames bacterial mutagenicity assay. Bupropion produced an increase in chromosomal aberrations in 1 of 3 in vivo rat bone marrow cytogenetic studies.

A fertility study in rats at doses up to 300 mg per kg per day revealed no evidence of impaired fertility.

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

The efficacy of ZYBAN as an aid to smoking cessation was demonstrated in 3 placebo‑controlled, double‑blind trials in nondepressed chronic cigarette smokers (n = 1,940, greater than or equal to 15 cigarettes per day). In these trials, ZYBAN was used in conjunction with individual smoking cessation counseling.

The first trial was a dose‑response trial conducted at 3 clinical centers. Subjects in this trial were treated for 7 weeks with 1 of 3 doses of ZYBAN (100, 150, or 300 mg per day) or placebo; quitting was defined as total abstinence during the last 4 weeks of treatment (Weeks 4 through 7). Abstinence was determined by subject daily diaries and verified by carbon monoxide levels in expired air.

Results of this dose‑response trial with ZYBAN demonstrated a dose‑dependent increase in the percentage of subjects able to achieve 4‑week abstinence (Weeks 4 through 7). Treatment with ZYBAN at both 150 and 300 mg per day was significantly more effective than placebo in this trial.

Table 5 presents quit rates over time in the multicenter trial by treatment group. The quit rates are the proportions of all subjects initially enrolled (i.e., intent-to-treat analysis) who abstained from Week 4 of the trial through the specified week. Treatment with ZYBAN (150 or 300 mg per day) was more effective than placebo in helping subjects achieve 4‑week abstinence. In addition, treatment with ZYBAN (7 weeks at 300 mg per day) was more effective than placebo in helping subjects maintain continuous abstinence through Week 26 (6 months) of the trial.

|

Abstinence from Week 4 through Specified Week |

Treatment Groups |

|||

|

Placebo (n = 151) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 100 mg/day (n = 153) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 150 mg/day (n = 153) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 300 mg/day (n = 156) % (95% CI) |

|

|

Week 7 (4-week quit) |

17% (11-23) |

22% (15-28) |

27%a (20-35) |

36%a (28-43) |

|

Week 12 |

14% (8-19) |

20% (13-26) |

20% (14-27) |

25%a (18-32) |

|

Week 26 |

11% (6-16) |

16% (11-22) |

18% (12-24) |

19%a (13-25) |

- a Significantly different from placebo ( P ≤0.05).

The second trial was a comparator trial conducted at 4 clinical centers. Four treatments were evaluated: ZYBAN 300 mg per day, nicotine transdermal system (NTS) 21 mg per day, combination of ZYBAN 300 mg per day plus NTS 21 mg per day, and placebo. Subjects were treated for 9 weeks. Treatment with ZYBAN was initiated at 150 mg per day while the subject was still smoking and was increased after 3 days to 300 mg per day given as 150 mg twice daily. NTS 21 mg per day was added to treatment with ZYBAN after approximately 1 week when the subject reached the target quit date. During Weeks 8 and 9 of the trial, NTS was tapered to 14 and 7 mg per day, respectively. Quitting, defined as total abstinence during Weeks 4 through 7, was determined by subject daily diaries and verified by expired air carbon monoxide levels. In this trial, subjects treated with any of the 3 treatments achieved greater 4‑week abstinence rates than subjects treated with placebo.

Table 6 presents quit rates over time by treatment group for the comparator trial.

|

Abstinence from Week 4 through Specified Week |

Treatment Groups |

|||

|

Placebo (n = 160) % (95% CI) |

Nicotine Transdermal System (NTS) 21 mg/day (n = 244) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 300 mg/day (n = 244) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 300 mg/day and NTS 21 mg/day (n = 245) % (95% CI) |

|

|

Week 7 (4-week quit) |

23% (17-30) |

36% (30-42) |

49% (43-56) |

58% (51-64) |

|

Week 10 |

20% (14-26) |

32% (26-37) |

46% (39-52) |

51% (45-58) |

When subjects in this trial were followed out to 1 year, the superiority of ZYBAN and the combination of ZYBAN and NTS over placebo in helping them to achieve abstinence from smoking was maintained. The continuous abstinence rate was 30% (95% CI: 24 to 35) in the subjects treated with ZYBAN and 33% (95% CI: 27 to 39) for subjects treated with the combination at 26 weeks compared with 13% (95% CI: 7 to 18) in the placebo group. At 52 weeks, the continuous abstinence rate was 23% (95% CI: 18 to 28) in the subjects treated with ZYBAN and 28% (95% CI: 23 to 34) for subjects treated with the combination, compared with 8% (95% CI: 3 to 12) in the placebo group. Although the treatment combination of ZYBAN and NTS displayed the highest rates of continuous abstinence throughout the trial, the quit rates for the combination were not significantly higher (P>0.05) than for ZYBAN alone.

The comparisons between ZYBAN, NTS, and combination treatment in this trial have not been replicated, and, therefore should not be interpreted as demonstrating the superiority of any of the active treatment arms over any other.

The third trial was a long‑term maintenance trial conducted at 5 clinical centers. Subjects in this trial received open‑label ZYBAN 300 mg per day for 7 weeks. Subjects who quit smoking while receiving ZYBAN (n = 432) were then randomized to ZYBAN 300 mg per day or placebo for a total trial duration of 1 year. Abstinence from smoking was determined by subject self‑report and verified by expired air carbon monoxide levels. This trial demonstrated that at 6 months, continuous abstinence rates were significantly higher for subjects continuing to receive ZYBAN than for those switched to placebo (P<0.05; 55% versus 44%).

Quit rates in clinical trials are influenced by the population selected. Quit rates in an unselected population may be lower than the above rates. Quit rates for ZYBAN were similar in subjects with and without prior quit attempts using nicotine replacement therapy.

Treatment with ZYBAN reduced withdrawal symptoms compared with placebo. Reductions on the following withdrawal symptoms were most pronounced: irritability, frustration, or anger; anxiety; difficulty concentrating; restlessness; and depressed mood or negative affect. Depending on the trial and the measure used, treatment with ZYBAN showed evidence of reduction in craving for cigarettes or urge to smoke compared with placebo.

Use in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

ZYBAN was evaluated in a randomized, double‑blind, comparator trial of 404 subjects with mild-to-moderate COPD defined as FEV1 greater than or equal to 35%, FEV1/FVC less than or equal to 70%, and a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and/or small airways disease. Subjects aged 36 to 76 years were randomized to ZYBAN 300 mg per day (n = 204) or placebo (n = 200) and treated for 12 weeks. Treatment with ZYBAN was initiated at 150 mg per day for 3 days while the subject was still smoking and increased to 150 mg twice daily for the remaining treatment period. Abstinence from smoking was determined by subject daily diaries and verified by carbon monoxide levels in expired air. Quitters were defined as subjects who were abstinent during the last 4 weeks of treatment. Table 7 shows quit rates in the COPD Trial.

|

4-Week Abstinence Period |

Treatment Groups |

|

|

Placebo (n = 200) % (95% CI) |

ZYBAN 300 mg/day (n = 204) % (95% CI) |

|

|

Weeks 9 through 12 |

12% (8-16) |

22%a (17-27) |

- a Significantly different from placebo ( P <0.05).

Postmarketing Neuropsychiatric Safety Outcome Trial

ZYBAN was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled trial that included subjects without a history of psychiatric disorder (non-psychiatric cohort, n = 3,912) and subjects with a history of psychiatric disorder (psychiatric cohort, n = 4003). Subjects aged 18 to 75 years, smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day were randomized 1:1:1:1 to ZYBAN 150 mg twice daily, varenicline 1 mg twice daily, nicotine replacement therapy patch (NRT) 21 mg per day with taper or placebo for a treatment period of 12 weeks; they were then followed for another 12 weeks post-treatment. [See Warnings and Precautions (5.2).]