Phenobarbital by Strides Pharma Science Limited / Strides Pharma Global Pte. Ltd. / Strides Pharma, Inc PHENOBARBITAL elixir

Phenobarbital by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Phenobarbital by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by Strides Pharma Science Limited, Strides Pharma Global Pte. Ltd., Strides Pharma, Inc. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

DESCRIPTION

The barbiturates are nonselective central nervous system (CNS) depressants that are primarily used as sedative-hypnotics. In subhypnotic doses, they are also used as anticonvulsants. The barbiturates and their sodium salts are subject to control under the Federal Controlled Substances Act.

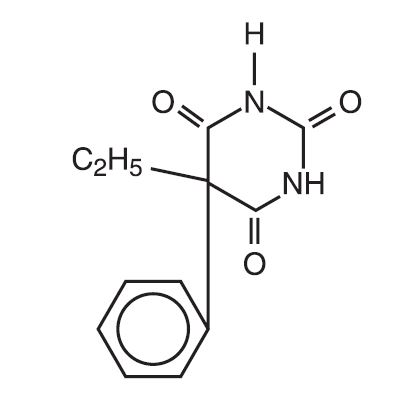

Phenobarbital is a barbituric acid derivative and occurs as white, odorless, small crystals or crystalline powder that is very slightly soluble in water; soluble in alcohol, in ether, and in solutions of fixed alkali hydroxides and carbonates; sparingly soluble in chloroform. Phenobarbital is 5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid and has the empirical formula C12H12N2O3. Its molecular weight is 232.24. It has the following structural formula:

Phenobarbital is a substituted pyrimidine derivative in which the basic structure is barbituric acid, a substance that has no CNS activity. CNS activity is obtained by substituting alkyl, alkenyl, or aryl groups on the pyrimidine ring. Each 5 mL (teaspoonful) contains 20.0 mg phenobarbital. The elixir also contains FD&C Red #40, flavors, glycerin, purified water, sucrose, and alcohol 15%.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Barbiturates are capable of producing all levels of CNS mood alteration, from excitation to mild sedation, hypnosis, and deep coma. Overdosage can produce death. In high enough therapeutic doses, barbiturates induce anesthesia.

Barbiturates depress the sensory cortex, decrease motor activity, alter cerebellar function, and produce drowsiness, sedation, and hypnosis.

Barbiturate-induced sleep differs from physiologic sleep. Sleep laboratory studies have demonstrated that barbiturates reduce the amount of time spent in the rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep or the dreaming stage. Also, Stages III and IV sleep are decreased. Following abrupt cessation of barbiturates used regularly, patients may experience markedly increased dreaming, nightmares, and/or insomnia. Therefore, withdrawal of a single therapeutic dose over 5 or 6 days has been recommended to lessen the REM rebound and disturbed sleep that contribute to the drug withdrawal syndrome (for example, the dose should be decreased from 3 to 2 doses/day for 1 week).

In studies, secobarbital sodium and pentobarbital sodium have been found to lose most of their effectiveness for both inducing and maintaining sleep by the end of 2 weeks of continued drug administration even with the use of multiple doses. As with secobarbital sodium and pentobarbital sodium, other barbiturates (including amobarbital) might be expected to lose their effectiveness for inducing and maintaining sleep after about 2 weeks. The short-, intermediate-, and to a lesser degree, long-acting barbiturates have been widely prescribed for treating insomnia. Although the clinical literature abounds with claims that the short-acting barbiturates are superior for producing sleep whereas the intermediate-acting compounds are more effective in maintaining sleep, controlled studies have failed to demonstrate these differential effects. Therefore, as sleep medications, the barbiturates are of limited value beyond short-term use.

Barbiturates have little analgesic action at subanesthetic doses. Rather, in subanesthetic doses, these drugs may increase the reaction to painful stimuli. All barbiturates exhibit anticonvulsant activity in anesthetic doses. However, of the drugs in this class, only phenobarbital, mephobarbital, and metharbital are effective as oral anticonvulsants in subhypnotic doses.

Barbiturates are respiratory depressants, and the degree of respiratory depression is dependent upon the dose. With hypnotic doses, respiratory depression produced by barbiturates is similar to that which occurs during physiologic sleep and is accompanied by a slight decrease in blood pressure and heart rate.

Studies in laboratory animals have shown that barbiturates cause reduction in the tone and contractility of the uterus, ureters, and urinary bladder. However, concentrations of the drugs required to produce this effect in humans are not reached with sedative-hypnotic doses.

Barbiturates do not impair the normal hepatic function but have been shown to induce liver microsomal enzymes, thus increasing and/or altering the metabolism of barbiturates and other drugs (see Drug Interactions under PRECAUTIONS).

Pharmacokinetics–Barbiturates are absorbed in varying degrees following oral or parenteral administration. The salts are more rapidly absorbed than are the acids. The rate of absorption is increased if the sodium salt is ingested as a dilute solution or taken on an empty stomach.

Duration of action, which is related to the rate at which the barbiturates are redistributed throughout the body, varies among persons and in the same person from time to time.

Phenobarbital is classified as a long-acting barbiturate when taken orally. Its onset of action is 1 hour or longer, and its duration of action ranges from 10 to 12 hours.

Barbiturates are weak acids that are absorbed and rapidly distributed to all tissues and fluids, with high concentrations in the brain, liver, and kidneys. Lipid solubility of the barbiturates is the dominant factor in their distribution within the body. The more lipid soluble the barbiturate, the more rapidly it penetrates all tissues of the body. Barbiturates are bound to plasma and tissue proteins to a varying degree with the degree of binding increasing directly as a function of lipid solubility.

Phenobarbital has the lowest lipid solubility, lowest plasma binding, lowest brain protein binding, the longest delay in onset of activity, and the longest duration of action. The plasma half-life for phenobarbital in adults ranges between 53 and 118 hours with a mean of 79 hours. The plasma half-life for phenobarbital in children and newborns (less than 48 hours old) ranges between 60 to 180 hours with a mean of 110 hours.

Barbiturates are metabolized primarily by the hepatic microsomal enzyme system, and the metabolic products are excreted in the urine, and, less commonly, in the feces. Approximately 25% to 50% of a dose of phenobarbital is eliminated unchanged in the urine. The excretion of unmetabolized barbiturate is one feature that distinguishes the long-acting category from those belonging to other categories, which are almost entirely metabolized. The inactive metabolites of the barbiturates are excreted as conjugates of glucuronic acid.

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

- CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

WARNINGS

1. Habit Forming–Phenobarbital may be habit forming. Tolerance and psychological and physical dependence may occur with continued use (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE and Pharmacokinetics under CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). Patients who have psychologic dependence on barbiturates may increase the dosage or decrease the dosage interval without consulting a physician and may subsequently develop a physical dependence on barbiturates. In order to minimize the possibility of overdosage or the development of dependence, the prescribing and dispensing of sedative-hypnotic barbiturates should be limited to the amount required for the interval until the next appointment. Abrupt cessation after prolonged use in a person who is dependent on the drug may result in withdrawal symptoms, including delirium, convulsions, and possibly death. Barbiturates should be withdrawn gradually from any patient known to be taking excessive doses over long periods of time (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

2. Acute or Chronic Pain–Caution should be exercised when barbiturates are administered to patients with acute or chronic pain, because paradoxical excitement could be induced or important symptoms could be masked. However, the use of barbiturates as sedatives in the postoperative surgical period and as adjuncts to cancer chemotherapy is well established.

3. Usage in Pregnancy–Barbiturates can cause fetal damage when administered to a pregnant woman. Retrospective, case-controlled studies have suggested a connection between the maternal consumption of barbiturates and a higher than expected incidence of fetal abnormalities. Barbiturates readily cross the placental barrier and are distributed throughout fetal tissues; the highest concentrations are found in the placenta, fetal liver, and brain. Fetal blood levels approach maternal blood levels following parenteral administration.

Withdrawal symptoms occur in infants born to women who receive barbiturates throughout the last trimester of pregnancy (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

If phenobarbital is used during pregnancy or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.

4. Usage in Children–Phenobarbital has been reported to be associated with cognitive deficits in children taking it for complicated febrile seizures.

5. Synergistic Effects–The concomitant use of alcohol or other CNS depressants may produce additive CNS depressant effects.

PRECAUTIONS

General–Barbiturates may be habit forming. Tolerance and psychological and physical dependence may occur with continued use (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

Barbiturates should be administered with caution, if at all, to patients who are mentally depressed, have suicidal tendencies, or have a history of drug abuse.

Elderly or debilitated patients may react to barbiturates with marked excitement, depression, or confusion. In some persons, especially children, barbiturates repeatedly produce excitement rather than depression.

In patients with hepatic damage, barbiturates should be administered with caution and initially in reduced doses. Barbiturates should not be administered to patients showing the premonitory signs of hepatic coma.

The systemic effects of exogenous and endogenous corticosteroids may be diminished by phenobarbital. Thus, this product should be administered with caution to patients with borderline hypoadrenal function, regardless of whether it is of pituitary or of primary adrenal origin.

Information for Patients–The following information and instructions should be given to patients receiving barbiturates.

1. The use of barbiturates carries with it an associated risk of psychological and/or physical dependence. The patient should be warned against increasing the dose of the drug without consulting a physician.

2. Barbiturates may impair the mental and/or physical abilities required for the performance of potentially hazardous tasks, such as driving a car or operating machinery. The patient should be cautioned accordingly.

3. Alcohol should not be consumed while taking barbiturates. The concurrent use of the barbiturates with other CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, narcotics, tranquilizers, and antihistamines) may result in additional CNS- depressant effects.

Laboratory Tests–Prolonged therapy with barbiturates should be accompanied by periodic laboratory evaluation of organ systems, including hematopoietic, renal, and hepatic systems (see General under PRECAUTIONS and ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Drug Interactions–Most reports of clinically significant drug interactions occurring with the barbiturates have involved phenobarbital. However, the application of this data to other barbiturates appears valid and warrants serial blood level determinations of the relevant drugs when there are multiple therapies.

1. Anticoagulants–Phenobarbital lowers the plasma levels of dicumarol and causes a decrease in anticoagulant activity as measured by the prothrombin time. Barbiturates can induce hepatic microsomal enzymes resulting in increased metabolism and decreased anticoagulant response of oral anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, acenocoumarol, dicumarol, and phenprocoumon). Patients stabilized on anticoagulant therapy may require dosage adjustments if barbiturates are added to or withdrawn from their dosage regimen.

2. Corticosteroids–Barbiturates appear to enhance the metabolism of exogenous corticosteroids, probably through the induction of hepatic microsomal enzymes. Patients stabilized on corticosteroid therapy may require dosage adjustments if barbiturates are added to or withdrawn from their dosage regimen.

3. Griseofulvin–Phenobarbital appears to interfere with the absorption of orally administered griseofulvin, thus decreasing its blood level. The effect of the resultant decreased blood levels of griseofulvin on therapeutic response has not been established. However, it would be preferable to avoid concomitant administration of these drugs.

4. Doxycycline–Phenobarbital has been shown to shorten the half-life of doxycycline for as long as 2 weeks after barbiturate therapy is discontinued. This mechanism is probably through the induction of hepatic microsomal enzymes that metabolize the antibiotic. If phenobarbital and doxycycline are administered concurrently, the clinical response to doxycycline should be monitored closely.

5. Phenytoin, Sodium Valproate, Valproic Acid–The effect of barbiturates on the metabolism of phenytoin appears to be variable. Some investigators report an accelerating effect, whereas others report no effect. Because the effect of barbiturates on the metabolism of phenytoin is not predictable, phenytoin and barbiturate blood levels should be monitored more frequently if these drugs are given concurrently. Sodium valproate and valproic acid increase the phenobarbital serum levels; therefore, phenobarbital blood levels should be closely monitored and appropriate dosage adjustments made as clinically indicated.

6. CNS Depressants–The concomitant use of other CNS depressants, including other sedatives or hypnotics, antihistamines, tranquilizers, or alcohol, may produce additive depressant effects.

7. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)–MAOIs prolong the effects of barbiturates, probably because metabolism of the barbiturate is inhibited.

8. Estradiol, Estrone, Progesterone, and other Steroidal Hormones–Pretreatment with or concurrent administration of phenobarbital may decrease the effect of estradiol by increasing its metabolism. There have been reports of patients treated with antiepileptic drugs (e.g., phenobarbital) who become pregnant while taking oral contraceptives. An alternate contraceptive method might be suggested to women taking phenobarbital.

Carcinogenesis–1. Animal Data. Phenobarbital sodium is carcinogenic in mice and rats after lifetime administration. In mice, it produced benign and malignant liver cell tumors. In rats, benign liver cell tumors were observed very late in life.

2. Human Data–In a 29-year epidemiologic study of 9,136 patients who were treated on an anticonvulsant protocol that included phenobarbital, results indicated a higher than normal incidence of hepatic carcinoma. Previously, some of these patients had been treated with thorotrast, a drug which is known to produce hepatic carcinomas. Thus, this study did not provide sufficient evidence that phenobarbital sodium is carcinogenic in humans.

A retrospective study of 84 children with brain tumors matched to 73 normal controls and 78 cancer controls (malignant disease other than brain tumors) suggested an association between exposure to barbiturates prenatally and an increased incidence of brain tumors.

Usage in Pregnancy–1. Teratogenic Effects. Pregnancy Category D–See Usage in Pregnancy under WARNINGS.

2. Nonteratogenic Effects–Reports of infants suffering from long-term barbiturate exposure in utero included the acute withdrawal syndrome of seizures and hyperirritability from birth to a delayed onset of up to 14 days (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

Labor and Delivery–Hypnotic doses of barbiturates do not appear to impair uterine activity significantly during labor. Full anesthetic doses of barbiturates decrease the force and frequency of uterine contractions. Administration of sedative-hypnotic barbiturates to the mother during labor may result in respiratory depression in the newborn. Premature infants are particularly susceptible to the depressant effects of barbiturates. If barbiturates are used during labor and delivery, resuscitation equipment should be available.

Data are not available to evaluate the effect of barbiturates when forceps delivery or other intervention is necessary or to determine the effect of barbiturates on the later growth, development, and functional maturation of the child.

Nursing Mothers–Caution should be exercised when phenobarbital is administered to a nursing woman, because small amounts of barbiturates are excreted in the milk.

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions have been reported:

CNS Depression–Residual sedation or "hangover", drowsiness, lethargy, and vertigo. Emotional disturbances and phobias may be accentuated. In some persons, barbiturates such as phenobarbital repeatedly produce excitement rather than depression, and the patient may appear to be inebriated. Irritability and hyperactivity can occur in children. Like other nonanalgesic hypnotic drugs, barbiturates such as phenobarbital, when given in the presence of pain, may cause restlessness, excitement, and even delirium. Rarely, the use of barbiturates results in the localized or diffuse myalgic, neuralgic, or arthritic pain, especially in psychoneurotic patients with insomnia. The pain may appear in paroxysms, is most intense in the early morning hours, and is most frequently located in the region of the neck, shoulder girdle, and upper limbs. Symptoms may last for days after the drug is discontinued.

Respiratory/Circulatory–Respiratory depression, apnea, circulatory collapse.

Allergic–Acquired hypersensitivity to barbiturates consists chiefly in allergic reactions that occur especially in persons who tend to have asthma, urticaria, angioedema, and similar conditions. Hypersensitivity reactions in this category include localized swelling, particularly of the eyelids, cheeks or lips, and erythematous dermatitis. Rarely, exfoliative dermatitis (e.g., Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) may be caused by phenobarbital and can prove fatal. The skin eruption may be associated with fever, delirium, and marked degenerative changes in the liver and other parenchymatous organs. In a few cases, megaloblastic anemia has been associated with the chronic use of phenobarbital.

Other–Nausea and vomiting; headache, osteomalacia.

The following adverse reactions and their incidence were compiled from surveillance of thousands of hospitalized patients who received barbiturates. Because such patients may be less aware of the milder adverse effects of barbiturates, the incidence of these reactions may be somewhat higher in fully ambulatory patients.

More than 1 in 100 Patients

The most common adverse reaction, estimated to occur at a rate of 1 to 3 patients per 100, is:

Nervous System: Somnolence

Less than 1 in 100 Patients

Adverse reactions estimated to occur at a rate of less than 1 in 100 patients are listed below, grouped by organ system and by decreasing order of occurrence:

Nervous System: Agitation, confusion, hyperkinesia, ataxia, CNS depression, nightmares, nervousness, psychiatric disturbance, hallucinations, insomnia, anxiety, dizziness, abnormality in thinking.

Respiratory System: Hypoventilation, apnea

Cardiovascular System: Bradycardia, hypotension, syncope

Digestive System: Nausea, vomiting, constipation

Other Reported Reactions: Headache, injection site reactions, hypersensitivity reactions (angioedema, skin rashes, exfoliative dermatitis), fever, liver damage, megaloblastic anemia following chronic phenobarbital use.

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Strides Pharma Inc. at 1-877-244-9825 or go to www.strides.com or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

-

DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

Controlled Substance–Phenobarbital is a Schedule IV drug.

Dependence–Barbiturates may be habit forming. Tolerance, psychological dependence, and physical dependence may occur, especially following prolonged use of high doses of barbiturates. Daily administrations in excess of 400 mg of pentobarbital or secobarbital for approximately 90 days is likely to produce some degree of physical dependence. A dosage of 600 to 800 mg taken for at least 35 days is sufficient to produce withdrawal seizures. The average daily dose for the barbiturate addict is usually about 1.5 g. As tolerance to barbiturates develops, the amount needed to maintain the same level of intoxication increases; tolerance to a fatal dosage, however, does not increase more than twofold. As this occurs, the margin between intoxicating dosage and fatal dosage becomes smaller.

Symptoms of acute intoxication with barbiturates include unsteady gait, slurred speech, and sustained nystagmus. Mental signs of chronic intoxication include confusion, poor judgment, irritability, insomnia, and somatic complaints.

Symptoms of barbiturate dependence are similar to those of chronic alcoholism. If an individual appears to be intoxicated with alcohol to a degree that is radically disproportionate to the amount of alcohol in his or her blood, the use of barbiturates should be suspected. The lethal dose of a barbiturate is far less if alcohol is also ingested.

The symptoms of barbiturate withdrawal can be severe and may cause death. Minor withdrawal symptoms may appear 8 to 12 hours after the last dose of a barbiturate. These symptoms usually appear in the following order: anxiety, muscle twitching, tremor of hands and fingers, progressive weakness, dizziness, distortion in visual perception, nausea, vomiting, insomnia, and orthostatic hypotension. Major withdrawal symptoms (convulsions and delirium) may occur within 16 hours and last up to 5 days after abrupt cessation of barbiturates. The intensity of withdrawal symptoms gradually declines over a period of approximately 15 days. Individuals susceptible to barbiturate abuse and dependence include alcoholics and opiate abusers as well as other sedative-hypnotic and amphetamine abusers.

Drug dependence on barbiturates arises from repeated administration of a barbiturate or agent with barbiturate-like effect on a continuous basis, generally in amounts exceeding therapeutic dose levels. The characteristics of drug dependence on barbiturates include: (a) a strong desire or need to continue taking the drug; (b) a tendency to increase the dose; (c) a psychic dependence on the effects of the drug related to subjective and individual appreciation of those effects; and (d) a physical dependence on the effects of the drug, requiring its presence for maintenance of homeostasis and resulting in a definite, characteristic and self-limited abstinence syndrome when the drug is withdrawn.

Treatment of barbiturate dependence consists of cautious and gradual withdrawal of the drug. Barbiturate-dependent patients can be withdrawn by using a number of different withdrawal regimens. In all cases, withdrawal requires an extended period of time. One method involves substituting a 30-mg dose of phenobarbital for each 100- to 200-mg dose of barbiturate that the patient has been taking. The total daily amount of phenobarbital is then administered in 3 or 4 divided doses, not to exceed 600 mg daily. If signs of withdrawal occur on the first day of treatment, a loading dose of 100 to 200 mg of phenobarbital may be administered IM in addition to the oral dose. After stabilization on phenobarbital, the total daily dose is decreased by 30 mg/day as long as withdrawal is proceeding smoothly. A modification of this regimen involves initiating treatment at the patient's regular dosage level and decreasing the daily dosage by 10% if tolerated by the patient.

Infants who are physically dependent on barbiturates may be given phenobarbital, 3 to 10 mg/kg/day. After withdrawal symptoms (hyperactivity, disturbed sleep, tremors, and hyperreflexia) are relieved, the dosage of phenobarbital should be gradually decreased and completely withdrawn over a 2-week period.

-

OVERDOSAGE

Signs and Symptoms–The onset of symptoms following a toxic oral exposure to phenobarbital may not occur until several hours following ingestion. The toxic dose of barbiturates varies considerably. In general, an oral dose of 1 g of most barbiturates produces serious poisoning in an adult. Death commonly occurs after 2 to 10 g of ingested barbiturate. The sedated, therapeutic blood levels of phenobarbital range between 5 to 40 mcg/mL; the usual lethal blood level ranges from 100 to 200 mcg/mL. Barbiturate intoxication may be confused with alcoholism, bromide intoxication, and various neurologic disorders. Potential tolerance must be considered when evaluating significance of dose and plasma concentration.

The manifestations of a long-acting barbiturate in overdose include nystagmus, ataxia, CNS depression, respiratory depression, hypothermia, and hypotension. Other findings may include absent or depressed reflexes and erythematous or hemorrhagic blisters (primarily at pressure points). Following massive exposure to phenobarbital, pulmonary edema, circulatory collapse with loss of peripheral vascular tone, cardiac arrest, and death may occur.

In extreme overdose, all electrical activity in the brain may cease, in which case a "flat" EEG normally equated with clinical death should not be accepted. This effect is fully reversible unless hypoxic damage occurs.

Consideration should be given to the possibility of barbiturate intoxication even in situations that appear to involve trauma.

Complications such as pneumonia, pulmonary edema, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, and renal failure may occur. Uremia may increase CNS sensitivity to barbiturates if renal function is impaired. Differential diagnosis should include hypoglycemia, head trauma, cerebrovascular accidents, convulsive states and diabetic coma.

Treatment–To obtain up-to-date information about the treatment of overdose, a good resource is your certified Regional Poison Control Center. Telephone numbers of certified poison control centers are listed in the Physicians' Desk Reference (PDR). In managing overdosage, consider the possibility of multiple drug overdoses, interaction among drugs, and unusual drug kinetics in your patient.

Protect the patient's airway and support ventilation and perfusion. Meticulously monitor and maintain, within acceptable limits, the patient's vital signs, blood gases, serum electrolytes, etc. Absorption of drugs from the gastrointestinal tract may be decreased by giving activated charcoal, which, in many cases, is more effective than emesis or lavage; consider charcoal instead of or in addition to gastric emptying. Repeated doses of charcoal over time may hasten elimination of some drugs that have been absorbed. Safeguard the patient's airway when employing gastric emptying or charcoal.

Alkalinization of urine hastens phenobarbital excretion, but dialysis and hemoperfusion are more effective and cause less troublesome alterations in electrolyte equilibrium. If the patient has chronically abused sedatives, withdrawal reactions may be manifest following acute overdose.

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The dose of phenobarbital must be individualized with full knowledge of its particular characteristics. Factors of consideration are the patient's age, weight, and condition.

Sedation: For sedation, the drug may be administered in single doses of 30 to 120 mg repeated at intervals; frequency will be determined by the patient's response. It is generally considered that no more than 400 mg of phenobarbital should be administered during a 24-hour period.

Adults: Daytime Sedation: 30 to 120 mg daily in 2 to 3 divided doses.

Oral Hypnotic: 100 to 200 mg

Anticonvulsant Use–Clinical laboratory reference values should be used to determine the therapeutic anticonvulsant level of phenobarbital in the serum. To achieve the blood levels considered therapeutic in pediatric patients, higher per-kilogram dosages are generally necessary for phenobarbital and most other anticonvulsants. In pediatric patients and infants, phenobarbital at a loading dose of 15 to 20 mg/kg produces blood levels of about 20 mcg/mL shortly after administration.

Phenobarbital has been used in the treatment and prophylaxis of febrile seizures. However, it has not been established that prevention of febrile seizures influences the subsequent development of epilepsy.

Adults: 60 to 200 mg/day

Pediatric Patients: 3 to 6 mg/kg/day.

Special Patient Population–Dosage should be reduced in the elderly or debilitated because these patients may be more sensitive to barbiturates. Dosage should be reduced for patients with impaired renal function or hepatic disease.

- HOW SUPPLIED

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

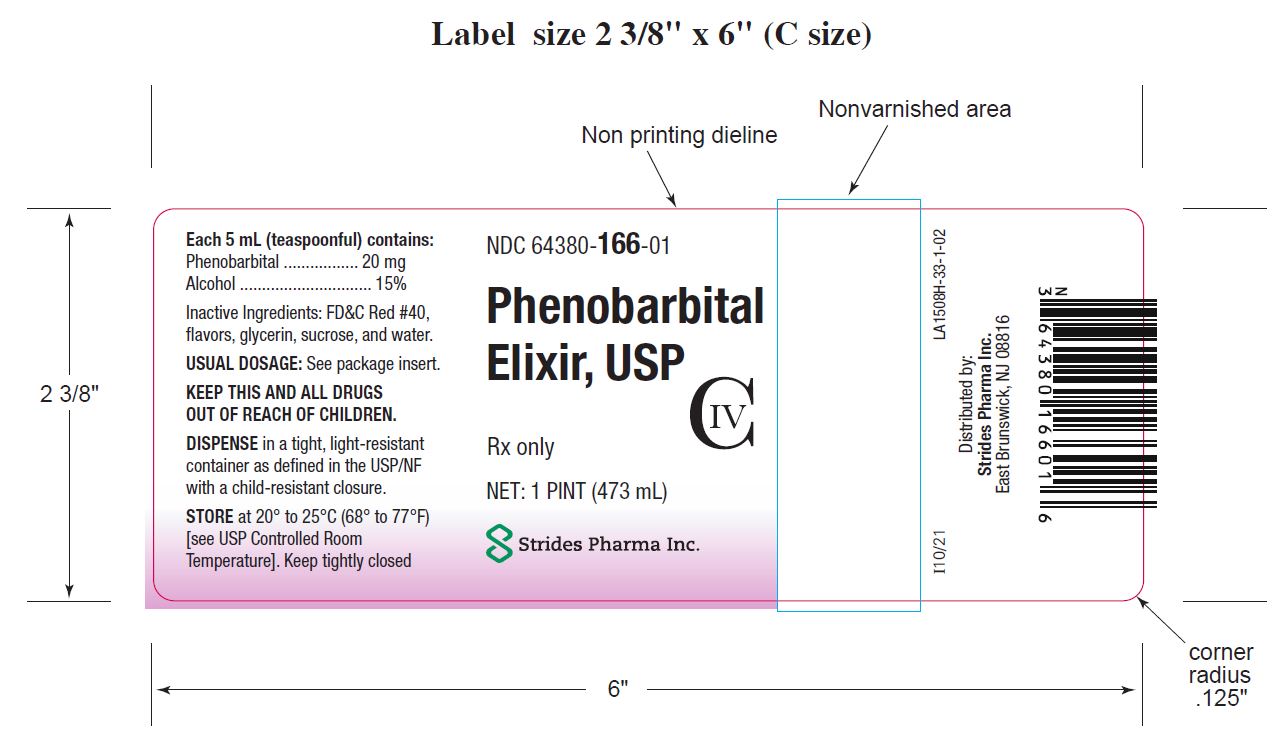

- PACKAGE LABEL.PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

PHENOBARBITAL

phenobarbital elixirProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 64380-166 Route of Administration ORAL DEA Schedule CIV Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength PHENOBARBITAL (UNII: YQE403BP4D) (PHENOBARBITAL - UNII:YQE403BP4D) PHENOBARBITAL 20 mg in 5 mL Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength FD&C RED NO. 40 (UNII: WZB9127XOA) GLYCERIN (UNII: PDC6A3C0OX) WATER (UNII: 059QF0KO0R) SUCROSE (UNII: C151H8M554) ALCOHOL (UNII: 3K9958V90M) Product Characteristics Color Score Shape Size Flavor ORANGE Imprint Code Contains Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 64380-166-01 473 mL in 1 BOTTLE, PLASTIC; Type 0: Not a Combination Product 04/04/2022 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date unapproved drug other 04/04/2022 Labeler - Strides Pharma Science Limited (650738743) Registrant - Strides Pharma Global Pte. Ltd. (659220961) Establishment Name Address ID/FEI Business Operations Strides Pharma, Inc 118344504 ANALYSIS(64380-166) , MANUFACTURE(64380-166) , PACK(64380-166)

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.