Estring by U.S. Pharmaceuticals / Pfizer Inc ESTRING- estradiol ring

Estring by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Estring by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by U.S. Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

WARNINGS

ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

Adequate diagnostic measures, including endometrial sampling when indicated, should be undertaken to rule out malignancy in all cases of undiagnosed persistent or recurring abnormal vaginal bleeding. (See WARNINGS, Malignant neoplasms, Endometrial cancer.)

CARDIOVASCULAR AND OTHER RISKS

Estrogens with or without progestins should not be used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease or dementia. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and WARNINGS, Cardiovascular disorders and Dementia.)

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) estrogen alone substudy reported increased risks of stroke and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in postmenopausal women (50 to 79 years of age) during 6.8 years and 7.1 years, respectively, of treatment with daily oral conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) relative to placebo. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and WARNINGS, Cardiovascular disorders.)

The estrogen plus progestin WHI substudy reported increased risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary emboli, and DVT in postmenopausal women (50 to 79 years of age) during 5.6 years of treatment with daily oral CE 0.625 mg combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg), relative to placebo. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and WARNINGS, Cardiovascular disorders and Malignant neoplasms, Breast cancer.)

The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a substudy of the WHI, reported increased risk of developing probable dementia in postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older during 5.2 years of treatment with daily CE 0.625 mg alone and during 4 years of treatment with daily CE 0.625 mg combined with MPA 2.5 mg, relative to placebo. It is unknown whether this finding applies to younger postmenopausal women. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and WARNINGS, Dementia and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

In the absence of comparable data, these risks should be assumed to be similar for other doses of CE and MPA and other combinations and dosage forms of estrogens and progestins. Because of these risks, estrogens with or without progestins should be prescribed at the lowest effective doses and for the shortest duration consistent with treatment goals and risks for the individual woman.

-

DESCRIPTION

ESTRING® (estradiol vaginal ring) is a slightly opaque ring with a whitish core containing a drug reservoir of 2 mg estradiol. Estradiol, silicone polymers and barium sulfate are combined to form the ring. When placed in the vagina, ESTRING releases estradiol, approximately 7.5 mcg per 24 hours, in a consistent stable manner over 90 days. ESTRING has the following dimensions: outer diameter 55 mm; cross-sectional diameter 9 mm; core diameter 2 mm. One ESTRING should be inserted into the upper third of the vaginal vault, to be worn continuously for three months.

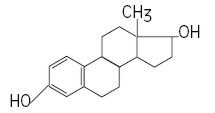

Estradiol is chemically described as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol. The molecular formula of estradiol is C18H24O2 and the structural formula is:

The molecular weight of estradiol is 272.39.

-

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Endogenous estrogens are largely responsible for the development and maintenance of the female reproductive system and secondary sexual characteristics. Although circulating estrogens exist in a dynamic equilibrium of metabolic interconversions, estradiol is the principal intracellular human estrogen and is substantially more potent than its metabolites, estrone and estriol, at the receptor level.

The primary source of estrogen in normally cycling adult women is the ovarian follicle, which secretes 70 to 500 mcg of estradiol daily, depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle. After menopause, most endogenous estrogen is produced by conversion of androstenedione, secreted by the adrenal cortex, to estrone by peripheral tissues. Thus, estrone and the sulfate conjugated form, estrone sulfate, are the most abundant circulating estrogens in postmenopausal women.

Estrogens act through binding to nuclear receptors in estrogen-responsive tissues. To date, two estrogen receptors have been identified. These vary in proportion from tissue to tissue.

Circulating estrogens modulate the pituitary secretion of the gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), through a negative feedback mechanism. Estrogens act to reduce the elevated levels of these hormones seen in postmenopausal women.

Pharmacokinetics

A. Absorption

Estrogens used in therapeutics are well absorbed through the skin, mucous membranes, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The vaginal delivery of estrogens circumvents first-pass metabolism.

In a Phase I study of 14 postmenopausal women, the insertion of ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) rapidly increased serum estradiol (E2) levels. The time to attain peak serum estradiol levels (Tmax) was 0.5 to 1 hour. Peak serum estradiol concentrations post-initial burst declined rapidly over the next 24 hours and were virtually indistinguishable from the baseline mean (range: 5 to 22 pg/mL). Serum levels of estradiol and estrone (E1) over the following 12 weeks during which the ring was maintained in the vaginal vault remained relatively unchanged (see Table 1).

The initial estradiol peak post-application of the second ring in the same women resulted in ~38 percent lower Cmax, apparently due to reduced systemic absorption via the treated vaginal epithelium. The relative systemic exposure from the initial peak of ESTRING accounted for approximately 4 percent of the total estradiol exposure over the 12-week period.

The release of estradiol from ESTRING was demonstrated in a Phase II study of 222 postmenopausal women who inserted up to four rings consecutively at three-month intervals. Systemic delivery of estradiol from ESTRING resulted in mean steady state serum estradiol estimates of 7.8, 7.0, 7.0, 8.1 pg/mL at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48, respectively. Similar reproducibility is also seen in levels of estrone. The systemic exposure to estradiol and estrone was within the range observed in untreated women after the first eight hours.

In postmenopausal women, mean dose of estradiol systemically absorbed unchanged from ESTRING is ~8 percent [95 percent CI: 2.8–12.8 percent] of the daily amount released locally.

B. Distribution

The distribution of exogenous estrogens is similar to that of endogenous estrogens. Estrogens are widely distributed in the body and are generally found in higher concentrations in the sex hormone target organs. Estrogens circulate in the blood largely bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin.

C. Metabolism

Exogenous estrogens are metabolized in the same manner as endogenous estrogens. Circulating estrogens exist in a dynamic equilibrium of metabolic interconversions. These transformations take place mainly in the liver. Estradiol is converted reversibly to estrone, and both can be converted to estriol, which is the major urinary metabolite. Estrogens also undergo enterohepatic recirculation via sulfate and glucuronide conjugation in the liver, biliary secretion of conjugates into the intestine, and hydrolysis in the intestine followed by reabsorption. In postmenopausal women, a significant proportion of the circulating estrogens exist as sulfate conjugates, especially estrone sulfate, which serves as a circulating reservoir for the formation of more active estrogens.

D. Excretion

Estradiol, estrone, and estriol are excreted in the urine along with glucuronide and sulfate conjugates.

Mean percent dose excreted in the 24-hour urine as estradiol, 4 and 12 weeks post-application of ESTRING in a Phase I study was 5 percent and 8 percent, respectively, of the daily released amount.

F. Drug Interactions

No formal drug interactions studies have been done with ESTRING.

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that systemic estrogens are metabolized partially by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). Therefore, inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 may affect estrogen metabolism. Inducers of CYP3A4 such as St. John's Wort preparations (Hypericum perforatum), phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and rifampin may reduce plasma concentrations of estrogens, possibly resulting in a decrease in systemic effects and/or changes in the uterine bleeding profile. Inhibitors of CYP3A4 such as erythromycin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, itraconazole, ritonavir and grapefruit juice may increase plasma concentrations of estrogens and may result in side effects.

-

CLINICAL STUDIES

Effects on vulvar and vaginal atrophy

Two pivotal controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy of ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) in the treatment of postmenopausal urogenital symptoms due to estrogen deficiency.

In a U.S. study where ESTRING was compared with conjugated estrogens vaginal cream, no difference in efficacy between the treatment groups was found with respect to improvement in the physician's global assessment of vaginal symptoms (83 percent and 82 percent of patients receiving ESTRING and cream, respectively) and in the patient's global assessment of vaginal symptoms (83 percent and 82 percent of patients receiving ESTRING and cream, respectively) after 12 weeks of treatment. In an Australian study, ESTRING was also compared with conjugated estrogens vaginal cream and no difference in the physician's assessment of improvement of vaginal mucosal atrophy (79 percent and 75 percent for ESTRING and cream, respectively) or in the patient's assessment of improvement in vaginal dryness (82 percent and 76 percent for ESTRING and cream, respectively) after 12 weeks of treatment.

In the U.S. study, symptoms of dysuria and urinary urgency improved in 74 percent and 65 percent, respectively, of patients receiving ESTRING as assessed by the patient. In the Australian study, symptoms of dysuria and urinary urgency improved in 90 percent and 71 percent, respectively, of patients receiving ESTRING as assessed by the patient.

In both studies, ESTRING and conjugated estrogens vaginal cream had a similar ability to reduce vaginal pH levels and to mature the vaginal mucosa (as measured cytologically using the maturation index and/or the maturation value) after 12 weeks of treatment. In supportive studies, ESTRING was also shown to have a similar significant treatment effect on the maturation of the urethral mucosa.

Endometrial overstimulation, as evaluated in non-hysterectomized patients participating in the U.S. study by the progestogen challenge test and pelvic sonogram, was reported for none of the 58 (0 percent) patients receiving ESTRING and 4 of the 35 patients (11 percent) receiving conjugated estrogens vaginal cream.

Of the U.S. women who completed 12 weeks of treatment, 95 percent rated product comfort for ESTRING as excellent or very good compared with 65 percent of patients receiving conjugated estrogens vaginal cream, 95 percent of ESTRING patients judged the product to be very easy or easy to use compared with 88 percent of cream patients, and 82 percent gave ESTRING an overall rating of excellent or very good compared with 58 percent for the cream.

Women's Health Initiative Studies

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) enrolled approximately 27,000 predominantly healthy postmenopausal women in two substudies to assess the risks and benefits of either the use of daily oral conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) alone or in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg) compared to placebo in the prevention of certain chronic diseases. The primary endpoint was the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) (nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], silent MI and CHD death), with invasive breast cancer as the primary adverse outcome studied. A "global index" included the earliest occurrence of CHD, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism (PE), endometrial cancer (only in the CE/MPA substudy), colorectal cancer, hip fracture, or death due to other cause. These substudies did not evaluate the effects of CE or CE/MPA on menopausal symptoms.

The estrogen alone substudy was stopped early because an increased risk of stroke was observed and it was deemed that no further information would be obtained regarding the risks and benefits of estrogen alone in predetermined primary endpoints. Results of the estrogen alone substudy, which included 10,739 women (average age 63 years, range 50 to 79; 75.3 percent White, 15.1 percent Black, 6.1 percent Hispanic, 3.6 percent Other), after an average follow-up of 6.8 years are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2: RELATIVE AND ABSOLUTE RISK SEEN IN THE ESTROGEN ALONE SUBSTUDY OF WHI Event Relative Risk

CE vs. Placebo

(95% nCI*)Placebo

n = 5,429CE

n = 5,310Absolute Risk per 10,000 Women-Years - * Nominal confidence intervals unadjusted for multiple looks and multiple comparisons.

- † Results are based on centrally adjudicated data for an average follow-up of 7.1 years.

- ‡ Not included in Global index.

- § Results are based on an average follow-up of 6.8 years.

- ¶ All deaths, except from breast or colorectal cancer, definite/probable CHD, PE or cerebrovascular disease.

- # A subset of the events was combined in a "global index" defined as the earliest occurrence of CHD events, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, hip fracture, or death due to other causes.

CHD events† 0.95 (0.79–1.16) 56 53 Nonfatal MI† 0.91 (0.73–1.14) 43 40 CHD death† 1.01 (0.71–1.43) 16 16 Stroke† 1.37 (1.09–1.73) 33 45 Ischemic† 1.55 (1.19–2.01) 25 38 Deep vein thrombosis†,‡ 1.47 (1.06–2.06) 15 23 Pulmonary embolism† 1.37 (0.90–2.07) 10 14 Invasive breast cancer† 0.80 (0.62–1.04) 34 28 Colorectal cancer§ 1.08 (0.75–1.55) 16 17 Hip fracture§ 0.61 (0.41–0.91) 17 11 Vertebral fractures§,‡ 0.62 (0.42–0.93) 17 11 Total fractures§,‡ 0.70 (0.63–0.79) 195 139 Death due to other causes§,¶ 1.08 (0.88–1.32) 50 53 Overall mortality§,‡ 1.04 (0.88–1.22) 78 81 Global index§,# 1.01 (0.91–1.12) 190 192 For those outcomes included in the WHI "global index" that reached statistical significance, the absolute excess risk per 10,000 women-years in the group treated with CE alone was 12 more strokes, while the absolute risk reduction per 10,000 women-years was 6 fewer hip fractures. The absolute excess risk of events included in the "global index" was a nonsignificant 2 events per 10,000 women-years. There was no difference between the groups in terms of all-cause mortality. (See BOXED WARNINGS, WARNINGS, and PRECAUTIONS.)

Final centrally adjudicated results for CHD events and centrally adjudicated results for invasive breast cancer incidence from the estrogen alone substudy, after an average follow-up of 7.1 years, reported no overall difference from primary CHD events (nonfatal MI, silent MI and CHD death) and invasive breast cancer incidence in women receiving CE alone compared with placebo (see Table 2).

Centrally adjudicated results for stroke events from the estrogen alone substudy, after an average follow-up of 7.1 years, reported no significant differences in distribution of stroke subtypes or severity, including fatal strokes, in women receiving CE alone compared to placebo. Estrogen alone increased the risk for ischemic stroke, and this excess risk was present in all subgroups of women examined (see Table 2).

The estrogen plus progestin substudy was also stopped early. According to the predefined stopping rule, after an average follow-up of 5.2 years of treatment, the increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular events exceeded the specified benefits included in the "global index." The absolute excess risk of events included in the "global index" was 19 per 10,000 women-years (relative risk [RR] 1.15, 95 percent nCI 1.03–1.28).

For those outcomes included in the WHI "global index" that reached statistical significance after 5.6 years of follow-up, the absolute excess risks per 10,000 women-years in the group treated with CE/MPA were 6 more CHD events, 7 more strokes, 10 more PEs, and 8 more invasive breast cancers, while the absolute risk reductions per 10,000 women-years were 7 fewer colorectal cancers and 5 fewer hip fractures. (See BOXED WARNINGS, WARNINGS, and PRECAUTIONS.)

Results of the estrogen plus progestin substudy, which included 16,608 women (average of 63 years, range 50 to 79; 83.9 percent White, 6.8 percent Black, 5.4 percent Hispanic, 3.9 percent Other), are presented in Table 3. These results reflect centrally adjudicated data after an average follow-up of 5.6 years.

TABLE 3: RELATIVE AND ABSOLUTE RISK SEEN IN THE ESTROGEN PLUS PROGESTIN SUBSTUDY OF WHI AT AN AVERAGE OF 5.6 YEARS* Event Relative Risk

CE/MPA vs. placebo

(95% nCI†)Placebo

n = 8,102CE/MPA

n = 8,506Absolute Risk per 10,000 Women-Years - * Results are based on centrally adjudicated data. Mortality data was not part of the adjudicated data; however, data at 5.2 years of follow-up showed no difference between the groups in terms of all-cause mortality (RR 0.98, 95 percent nCI, 0.82–1.18).

- † Nominal confidence intervals unadjusted for multiple looks and multiple comparisons.

- ‡ Includes metastasis and non-metastatic breast cancer, with the exception of in situ breast cancer.

CHD events 1.24 (1.00–1.54) 33 39 Nonfatal MI 1.28 (1.00–1. 63) 25 31 CHD death 1.10 (0.70–1.75) 8 8 All strokes 1.31 (1.02–1.68) 24 31 Ischemic Stroke 1.44 (1.09–1.90) 18 26 Deep vein thrombosis 1.95 (1.43–2.67) 13 26 Pulmonary embolism 2.13 (1.45–3.11) 8 18 Invasive breast cancer‡ 1.24 (1.01–1.54) 33 41 Invasive colorectal cancer 0.56 (0.38–0.81) 16 9 Endometrial cancer 0.81 (0.48–1.36) 7 6 Cervical cancer 1.44 (0.47–4.42) 1 2 Hip fracture 0.67 (0.47–0.96) 16 11 Vertebral fracture 0.65 (0.46–0.92) 17 11 Lower arm/wrist fractures 0.71 (0.59–0.85) 62 44 Total fractures 0.76 (0.69–0.83) 199 152 Women's Health Initiative Memory Study

The estrogen alone Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a substudy of the WHI, enrolled 2,947 predominantly healthy postmenopausal women 65 years of age and older (45 percent were 65 to 69 years of age, 36 percent were 70 to 74 years of age, and 19 percent were 75 years of age and older) to evaluate the effects of daily conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) on the incidence of probable dementia (primary outcome) compared with placebo.

After an average follow-up of 5.2 years, 28 women in the estrogen alone group (37 per 10,000 women-years) and 19 in the placebo group (25 per 10,000 women-years) were diagnosed with probable dementia. The relative risk of probable dementia in the estrogen alone group was 1.49 (95 percent CI, 0.83–2.66) compared to placebo. It is unknown whether these findings apply to younger postmenopausal women. (See BOXED WARNINGS, WARNINGS, Dementia, and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

The estrogen plus progestin WHIMS substudy enrolled 4,532 predominantly healthy postmenopausal women 65 years of age and older (47 percent were 65 to 69 years of age, 35 percent were 70 to 74 years of age, and 18 percent were 75 years of age and older) to evaluate the effects of daily CE 0.625 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg) on the incidence of probable dementia (primary outcome) compared with placebo.

After an average follow-up of 4 years, 40 women in the estrogen plus progestin group (45 per 10,000 women-years) and 21 in the placebo group (22 per 10,000 women-years) were diagnosed with probable dementia. The relative risk of probable dementia in the hormone therapy group was 2.05 (95 percent CI, 1.21–3.48) compared to placebo.

When data from the two populations were pooled as planned in the WHIMS protocol, the reported overall relative risk for probable dementia was 1.76 (95 percent CI, 1.19–2.60). Differences between groups became apparent in the first year of treatment. It is unknown whether these findings apply to younger postmenopausal women. (See BOXED WARNING, WARNINGS, Dementia, and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

- INDICATIONS AND USAGE

-

CONTRAINDICATIONS

ESTRING vaginal ring should not be used in women with any of the following conditions:

- Undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding.

- Known, suspected, or history of cancer of the breast.

- Known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia.

- Active deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or a history of these conditions.

- Active or recent (within the past year) arterial thromboembolic disease (for example, stroke and myocardial infarction).

- Known liver dysfunction or disease.

- Known hypersensitivity to any of the ingredients in ESTRING.

- Known or suspected pregnancy.

-

WARNINGS

See BOXED WARNINGS

ESTRING is a vaginal administered product with low systemic absorption following continuous use for 3 months (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Pharmacokinetics, Absorption). The estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI utilized systemically-absorbed oral estrogen/progestin. However, the warnings, precautions, and adverse reactions associated with oral estrogen and/or progestin therapy should be considered in the absence of comparable data with other dosage forms of estrogens and/or progestins.

1. Cardiovascular disorders

An increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) has been reported with estrogen alone therapy. An increased risk of stroke, DVT, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction has been reported with estrogen plus progestin therapy. Should any of these occur or be suspected, estrogens with or without progestins should be discontinued immediately.

Risk factors for arterial vascular disease (for example, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity) and/or venous thromboembolism (VTE) (for example, personal history or family history of VTE, obesity, and systemic lupus erythematosus) should be managed appropriately.

a. Stroke

In the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), estrogen alone substudy, a statistically significant increased risk of stroke was reported in women receiving daily conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) compared to placebo (45 versus 33 per 10,000 women-years). The increase in risk was demonstrated in year one and persisted. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

In the estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI, a statistically significant increased risk of stroke was reported in women receiving daily CE 0.625 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg) compared to placebo (31 versus 24 per 10,000 women-years). The increase in risk was demonstrated after the first year and persisted. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

b. Coronary heart disease

In the estrogen alone substudy of WHI, no overall effect on coronary heart disease (CHD) events (defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], silent MI and CHD death) was reported in women receiving estrogen alone compared to placebo. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

In the estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI, no statistically significant increase of CHD events was reported in women receiving CE/MPA compared to women receiving placebo (39 versus 33 per 10,000 women-years). An increase in relative risk was demonstrated in year 1, and a trend toward decreasing relative risk was reported in years 2 through 5. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

In postmenopausal women with documented heart disease (n = 2,763, average age 66.7 years), in a controlled clinical trial of secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study [HERS]) treatment with daily CE 0.625 mg/MPA 2.5 mg demonstrated no cardiovascular benefit. During an average follow-up of 4.1 years, treatment with CE/MPA did not reduce the overall rate of CHD events in postmenopausal women with established coronary heart disease. There were more CHD events in the CE/MPA-treated group than in the placebo group in year one, but not during the subsequent years. Two thousand three hundred and twenty-one (2,321) women from the original HERS trial agreed to participate in an open label extension of HERS, HERS II. Average follow-up in HERS II was an additional 2.7 years, for a total of 6.8 years overall. Rates of CHD events were comparable among women in the combined continuous CE/MPA treatment group and the placebo group in HERS, HERS II, and overall.

c. Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

In the estrogen alone substudy of WHI, the risk of VTE (DVT and pulmonary embolism [PE]) was reported to be increased for women receiving daily CE compared to women receiving placebo (30 versus 22 per 10,000 women-years), although only the increased risk of DVT reached statistical significance (23 versus 15 per 10,000 women-years). The increase in VTE risk was demonstrated during the first two years. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

In the estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI, a statistically significant two-fold greater rate of VTE was reported in women receiving daily CE/MPA compared to women receiving placebo (35 versus 17 per 10,000 women-years). Statistically significant increases in risk for both DVT (26 versus 13 per 10,000 women-years) and PE (18 versus 8 per 10,000 women-years) were also demonstrated. The increase in VTE risk was observed during the first year and persisted. (See CLINICAL STUDIES.)

If feasible, estrogens should be discontinued at least 4 to 6 weeks before surgery of the type associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, or during periods of prolonged immobilization.

2. Malignant neoplasms

a. Endometrial cancer

An increased risk of endometrial cancer has been reported with the use of unopposed estrogen therapy in women with a uterus. The reported endometrial cancer risk among unopposed estrogen users is about 2 to 12-times greater than in nonusers, and appears dependent on duration of treatment and on estrogen dose. Most studies show no significant increased risk associated with use of estrogens for less than 1 year. The greatest risk appears associated with prolonged use, with increased risks of 15 to 24-fold for 5 to 10 years or more. This risk has been shown to persist for at least 8 to 15 years after estrogen therapy is discontinued.

Clinical surveillance of all women taking estrogen plus progestin therapy is important. Adequate diagnostic measures, including endometrial sampling when indicated, should be undertaken to rule out malignancy in all cases of undiagnosed persistent or recurring abnormal vaginal bleeding. There is no evidence that the use of natural estrogens result in a different endometrial risk profile than synthetic estrogens of equivalent estrogen dose. Adding a progestin to estrogen therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia, which may be a precursor to endometrial cancer.

b. Breast cancer

The use of estrogens and progestins by postmenopausal women has been reported to increase the risk of breast cancer in some studies. Observational studies have also reported an increased risk of breast cancer for estrogen plus progestin therapy, and a smaller increased risk for estrogen alone therapy, after several years of use. The risk increased with duration of use, and appeared to return to baseline over about 5 years after stopping treatment (only the observational studies have substantial data on risk after stopping). Observational studies also suggest that the risk of breast cancer was greater, and became apparent earlier, with estrogen plus progestin therapy as compared to estrogen alone therapy. However, these studies have not found significant variation in the risk of breast cancer among different estrogen plus progestin combinations, doses, or routes of administration.

The most important randomized clinical trial providing information about this issue is the Women Health Initiative (WHI) substudy of daily conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg) (see CLINICAL STUDIES). In the estrogen alone substudy of WHI, after an average of 7.1 years of follow-up, daily CE 0.625 mg was not associated with an increased risk of invasive breast cancer (relative risk [RR] 0.80, 95 percent nominal confidence interval [nCI] 0.62–1.04).

In the estrogen plus progestin substudy, after a mean follow-up of 5.6 years, the WHI substudy reported an increased risk of breast cancer in women who took daily CE/MPA. In this substudy, prior use of estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestin therapy was reported by 26 percent of the women. The relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.24 (95 percent nCI, 1.01–1.54), and the absolute risk was 41 versus 33 cases per 10,000 women-years, for estrogen plus progestin compared with placebo, respectively. Among women who reported prior use of hormone therapy, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.86, and the absolute risk was 46 versus 25 cases per 10,000 women-years, for CE/MPA compared with placebo. Among women who reported no prior use of hormone therapy, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.09, and the absolute risk was 40 versus 36 per 10,000 women-years for estrogen plus progestin compared with placebo. In the same substudy, invasive breast cancers were larger and diagnosed at a more advanced stage in the CE/MPA group compared with the placebo group. Metastatic disease was rare with no apparent difference between the two groups. Other prognostic factors such as histologic subtype, grade, and hormone receptor status did not differ between the groups.

The use of estrogen alone and estrogen plus progestin has been reported to result in an increase in abnormal mammograms requiring further evaluation. All women should receive yearly breast exams by a healthcare provider and perform monthly self-examinations. In addition, mammography examinations should be scheduled based on patient age, risk factors, and prior mammogram results.

c. Ovarian cancer

The estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI reported that daily CE/MPA increased the risk of ovarian cancer. After an average follow-up of 5.6 years, the relative risk for ovarian cancer for CE/MPA versus placebo was 1.58 (95 percent nCI, 0.77–3.24) but was not statistically significant. The absolute risk for CE/MPA was 4.2 versus 2.7 cases per 10,000 women-years. In some epidemiologic studies, the use of estrogen-only products, in particular for 10 or more years, has been associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Other epidemiologic studies have not found these associations.

3. Dementia

In the estrogen alone Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a substudy of WHI, a population of 2,947 hysterectomized women aged 65 to 79 years was randomized to daily conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg) or placebo. In the estrogen plus progestin WHIMS substudy, a population of 4,532 postmenopausal women aged 65 to 79 years was randomized to daily CE 0.625 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA 2.5 mg) or placebo.

In the estrogen alone substudy, after an average follow-up of 5.2 years, 28 women in the CE alone group and 19 women in the placebo group were diagnosed with probable dementia. The relative risk of probable dementia for estrogen CE alone versus placebo was 1.49 (95 percent CI, 0.83–2.66). The absolute risk of probable dementia for CE alone versus placebo was 37 versus 25 cases per 10,000 women-years. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

In the estrogen plus progestin substudy, after an average follow-up of 4 years, 40 women in the CE/MPA group and 21 women in the placebo group were diagnosed with probable dementia. The relative risk of probable dementia for CE/MPA versus placebo was 2.05 (95 percent CI, 1.21–3.48). The absolute risk of probable dementia for CE/MPA versus placebo was 45 versus 22 cases per 10,000 women-years. (See CLINICAL STUDIES and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

When data from the two populations were pooled as planned in the WHIMS protocol, the reported overall relative risk for probable dementia was 1.76 (95 percent CI, 1.19–2.60). Since both substudies were conducted in women aged 65 to 79 years, it is unknown whether these findings apply to younger postmenopausal women. (See BOXED WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Geriatric Use.)

4. Gallbladder disease

A two- to four-fold increase in the risk of gallbladder disease requiring surgery in postmenopausal women receiving estrogens has been reported.

5. Hypercalcemia

Estrogen administration may lead to severe hypercalcemia in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases. If hypercalcemia occurs, use of the drug should be stopped and appropriate measures taken to reduce the serum calcium level.

6. Visual abnormalities

Retinal vascular thrombosis has been reported in patients receiving estrogens. Discontinue medication pending examination if there is sudden partial or complete loss of vision, or a sudden onset of proptosis, diplopia, or migraine. If examination reveals papilledema or retinal vascular lesions, estrogens should be discontinued.

-

PRECAUTIONS

A. General

1. Addition of a progestin when a woman has not had a hysterectomy

Studies of the addition of a progestin for 10 or more days of a cycle of estrogen administration, or daily with estrogen in a continuous regimen, have reported a lowered incidence of endometrial hyperplasia than would be induced by estrogen treatment alone. Endometrial hyperplasia may be a precursor to endometrial cancer.

There are, however, possible risks that may be associated with the use of progestins with estrogens compared to estrogen alone regimens. These include a possible increased risk of breast cancer, adverse effects on lipoprotein metabolism (lowering HDL, raising LDL), and impairment of glucose tolerance.

2. Elevated blood pressure

In a small number of case reports, substantial increases in blood pressure have been attributed to idiosyncratic reactions to estrogens. In a large, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, a generalized effect of estrogen therapy on blood pressure was not seen. Blood pressure should be monitored at regular intervals with estrogen use.

3. Hypertriglyceridemia

In patients with preexisting hypertriglyceridemia, estrogen therapy may be associated with elevations of plasma triglycerides leading to pancreatitis and other complications. Consider discontinuation of treatment if pancreatitis or other complications develop.

4. Impaired liver function and past history of cholestatic jaundice

ESTRING vaginal ring should be used with caution in patients with impaired liver function. Estrogens may be poorly metabolized in patients with impaired liver function. For patients with a history of cholestatic jaundice associated with past estrogen use or with pregnancy, caution should be exercised and in the case of recurrence, medication should be discontinued.

5. Hypothyroidism

Estrogen administration leads to increased thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) levels. Patients with normal thyroid function can compensate for the increased TBG by making more thyroid hormone, thus maintaining free T4 and T3 serum concentrations in the normal range. Patients dependent on thyroid hormone replacement therapy who are also receiving estrogens may require increased doses of their thyroid replacement therapy. These patients should have their thyroid function monitored in order to maintain their free thyroid hormone levels in an acceptable range.

7. Fluid retention

Estrogens may cause some degree of fluid retention. Patients who have conditions that might be influenced by this factor, such as a cardiac or renal dysfunction, warrant careful observation when estrogens are prescribed.

8. Exacerbation of endometriosis

Endometriosis may be exacerbated with administration of estrogens. A few cases of malignant transformation of residual endometrial implants have been reported in women treated post-hysterectomy with estrogen alone therapy. For patients known to have residual endometriosis post-hysterectomy, the addition of progestin should be considered.

9. Exacerbation of other conditions

Estrogens may cause an exacerbation of asthma, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, migraine or porphyria, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hepatic hemangiomas and should be used with caution in women with these conditions.

10. Location of ESTRING

Some women have experienced moving or gliding of ESTRING within the vagina. Instances of ESTRING being expelled from the vagina in connection with moving the bowels, strain, or constipation have been reported. If this occurs, ESTRING can be rinsed in lukewarm water and reinserted into the vagina by the patient.

11. Vaginal Irritation

ESTRING may not be suitable for women with narrow, short, or stenosed vaginas. Narrow vagina, vaginal stenosis, prolapse, and vaginal infections are conditions that make the vagina more susceptible to ESTRING-caused irritation or ulceration. Women with signs or symptoms of vaginal irritation should alert their physician.

12. Vaginal Infection

Vaginal infection is generally more common in postmenopausal women due to the lack of the normal flora of fertile women, especially lactobacillus, and the subsequent higher pH. Vaginal infections should be treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy before initiation of ESTRING. If a vaginal infection develops during use of ESTRING, then ESTRING should be removed and reinserted only after the infection has been appropriately treated.

B. Information for the Patient

Physicians are advised to discuss the PATIENT INFORMATION leaflet with patients for whom they prescribe ESTRING.

C. Laboratory Tests

Serum follicle stimulating hormone and estradiol levels have not been shown to be useful in the management of moderate to severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy.

D. Drug and Laboratory Test Interactions

- Accelerated prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet aggregation time; increased platelet count; increased factors II, VII antigen, VIII antigen, VIII coagulant activity, IX, X, XII, VII-X complex, II-VII-X complex, and beta-thromboglobulin; decreased levels of anti-factor Xa and antithrombin III, decreased antithrombin III activity; increased levels of fibrinogen and fibrinogen activity; increased plasminogen antigen and activity.

- Increased thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) levels leading to increased circulating total thyroid hormone levels, as measured by protein-bound iodine (PBI), T4 levels (by column or by radioimmunoassay) or T3 levels by radioimmunoassay. T3 resin uptake is decreased, reflecting the elevated TBG. Free T4 and free T3 concentrations are unaltered. Patients on thyroid replacement therapy may require higher doses of thyroid hormone.

- Other binding proteins may be elevated in serum, (i.e., corticosteroid binding globulin [CBG], sex hormone-binding globulin [SHBG]), leading to increased circulating corticosteroid and sex steroids, respectively. Free hormone concentrations may be decreased. Other plasma proteins may be increased (angiotensinogen/renin substrate, alpha-1-antitrypsin, ceruloplasmin).

- Increased plasma HDL and HDL2 cholesterol subfraction concentrations, reduced LDL cholesterol concentration, increased triglycerides levels.

- Impaired glucose tolerance.

E. Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertility

Long-term continuous administration of natural and synthetic estrogens in certain animal species increases the frequency of carcinomas of the breast, uterus, cervix, vagina, testes and liver.

F. Pregnancy

ESTRING should not be used during pregnancy. (See CONTRAINDICATIONS.)

There appears to be little or no increased risk of birth defects in children born to women who have used estrogens and progestins as an oral contraceptive inadvertently during early pregnancy.

G. Nursing Mothers

ESTRING should not be used during lactation. Estrogen administration to nursing mothers has been shown to decrease the quantity and quality of the breast milk. Detectable amounts of estrogens have been identified in the milk of mothers receiving this drug.

H. Pediatric Use

ESTRING is not indicated for pediatric use and no clinical data have been collected in children.

I. Geriatric Use

There have not been sufficient numbers of geriatric patients involved in studies utilizing ESTRING to determine whether those over 65 years of age differ from younger subjects in their response to ESTRING.

In the estrogen alone substudy of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study, 46 percent (n = 4,943) of subjects were 65 years of age and older, while 7.1 percent (n = 767) of subjects were 75 years of age and older. There was a higher relative risk (daily CE 0.625 mg versus placebo) of stroke in women less than 75 years of age compared to women 75 years and older.

In the estrogen alone substudy of the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a substudy of WHI, a population of 2,947 hysterectomized women, aged 65 to 79 years of age, was randomized to receive daily conjugated estrogens (CE 0.625 mg daily) or placebo. After an average follow-up of 5.2 years, the relative risk (CE versus placebo) of probable dementia was 1.49 (95 percent CI, 0.83–2.66). The absolute risk of developing probable dementia with estrogen alone was 37 versus 25 cases per 10,000 women-years compared with placebo.

Of the total number of subjects in the estrogen plus progestin substudy of WHI, 44 percent (n = 7,320) were 65 years of age and older, while 6.6 percent (n = 1,095) were 75 years of age and older. In women 75 years of age and older compared to women less than 75 years of age, there was a higher relative risk of nonfatal stroke and invasive breast cancer in the estrogen plus progestin group versus placebo. In women greater than 75, the increased risk of nonfatal stroke and invasive breast cancer observed in the estrogen plus progestin group compared to placebo was 75 versus 24 per 10,000 women-years and 52 versus 12 per 10,000 women-years, respectively.

In the estrogen plus progestin WHIMS substudy, a population of 4,532 postmenopausal women, aged 65 to 79 years, was randomized to receive CE 0.625 mg/MPA 2.5 mg or placebo. In the estrogen plus progestin group, after an average follow-up of 4 years, the relative risk (CE/MPA versus placebo) of probable dementia was 2.05 (95 percent CI, 1.21–3.48). The absolute risk of developing probable dementia with CE/MPA was 45 versus 22 cases per 10,000 women-years compared with placebo.

Seventy-nine percent of the cases of probable dementia occurred in women that were older than 70 for the CE alone group, and 82 percent of the cases of probable dementia occurred in women who were older than 70 in the CE/MPA group. The most common classification of probable dementia in both the treatment groups and placebo groups was Alzheimer's disease.

When data from the two populations were pooled as planned in the WHIMS protocol, the reported overall relative risk for probable dementia was 1.76 (95 percent CI, 1.19–2.60). Since both substudies were conducted in women aged 65 to 79 years, it is unknown whether these findings apply to younger postmenopausal women. (See BOXED WARNINGS and WARNINGS, Dementia.)

-

ADVERSE REACTIONS

See BOXED WARNINGS, WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

In the two pivotal controlled studies, discontinuation of treatment due to an adverse event was required by 5.4 percent of patients receiving ESTRING and 3.9 percent of patients receiving conjugated estrogens vaginal cream. The most common reasons for withdrawal from ESTRING treatment due to an adverse event were vaginal discomfort and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The adverse events reported with a frequency of 3 percent or greater in the two pivotal controlled studies by patients receiving ESTRING or conjugated estrogens vaginal cream are listed in Table 4.

Table 4: Adverse Events Reported by 3 Percent or More of Patients Receiving Either ESTRING or Conjugated Estrogens Vaginal Cream in Two Pivotal Controlled Studies ADVERSE EVENT ESTRING

(n = 257)

%Conjugated Estrogens Vaginal Cream (n = 129)

%Musculoskeletal Back Pain 6 8 Arthritis 4 2 Arthralgia 3 5 Skeletal Pain 2 4 CNS/Peripheral Nervous System Headache 13 16 Psychiatric Insomnia 4 0 Gastrointestinal Abdominal Pain 4 2 Nausea 3 2 Respiratory Upper Respiratory Tract Infection 5 6 Sinusitis 4 3 Pharyngitis 1 3 Urinary Urinary Tract Infection 2 7 Female Reproductive Leukorrhea 7 3 Vaginitis 5 2 Vaginal Discomfort/Pain 5 5 Vaginal Hemorrhage 4 5 Asymptomatic Genital Bacterial Growth 4 6 Breast Pain 1 7 Resistance Mechanisms Genital Moniliasis 6 7 Body as a Whole Flu-Like Symptoms 3 2 Hot Flushes 2 3 Allergy 1 4 Miscellaneous Family Stress 2 3 Other adverse events (listed alphabetically) occurring at a frequency of 1 to 3 percent in the two pivotal controlled studies by patients receiving ESTRING include: anxiety, bronchitis, chest pain, cystitis, dermatitis, diarrhea, dyspepsia, dysuria, flatulence, gastritis, genital eruption, urogenital pruritus, hemorrhoids, leg edema, migraine, otitis media, skin hypertrophy, syncope, toothache, tooth disorder, urinary incontinence.

Post-Marketing Experience

- A few cases of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) have been reported in women using vaginal rings. TSS is a rare, but serious disease that may cause death. Warning signs of TSS include fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pain, dizziness, faintness, or a sunburn-rash on face and body.

- A few cases of ring adherence to the vaginal wall, making ring removal difficult, have been reported. Vaginal wall ulceration or erosion should be carefully evaluated. If an ulceration or erosion has occurred, consideration should be given to leaving the ring out and not replacing it until healing is complete in order to prevent the ring from adhering to the healing tissue.

- A few cases of bowel obstruction and vaginal ring use have been reported. Persistent abdominal complaints consistent with obstruction should be carefully evaluated.

The following additional adverse events were reported at least once by patients receiving ESTRING in the worldwide clinical program, which includes controlled and uncontrolled studies. A causal relationship with ESTRING has not been established.

Body as a Whole: allergic reaction

CNS/Peripheral Nervous System: dizziness

Gastrointestinal: enlarged abdomen, vomiting

Metabolic/Nutritional Disorders: weight decrease or increase

Musculoskeletal: arthropathy (including arthrosis)

Psychiatric: depression, decreased libido, nervousness

Reproductive: breast engorgement, breast enlargement, intermenstrual bleeding, genital edema, vulval disorder

Skin/Appendages: pruritus, pruritus ani

Urinary: micturition frequency, urethral disorder

Vascular: thrombophlebitis

Vision: abnormal vision

The following additional adverse reactions have been reported with estrogens:

Genitourinary system: abnormal uterine bleeding/spotting; dysmenorrheal/pelvic pain; increase in size of uterine leiomyomata; vaginitis, including vaginal candidiasis; change in amount of cervical secretion; changes in cervical ectropion; ovarian cancer; endometrial hyperplasia; endometrial cancer

Breasts: tenderness, enlargement, pain, nipple discharge, galactorrhea; fibrocystic breast changes; breast cancer

Cardiovascular: deep and superficial venous thrombosis; pulmonary embolism; thrombophlebitis; myocardial infarction; stroke; increase in blood pressure

Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting; abdominal cramps, bloating; cholestatic jaundice; increased incidence of gallbladder disease; pancreatitis, enlargement of hepatic hemangiomas

Skin: chloasma or melasma that may persist when drug is discontinued; erythema multiforme; erythema nodosum; hemorrhagic eruption; loss of scalp hair; hirsutism, rash

Eyes: retinal vascular thrombosis; intolerance to contact lenses

Central Nervous System: headache; migraine; dizziness; mental depression; exacerbation of chorea; nervousness; mood disturbances; irritability; exacerbation of epilepsy, dementia

Miscellaneous: increase or decrease in weight; glucose intolerance; aggravation of porphyria; edema; arthralgias; leg cramps; changes in libido; angioedema; anaphylactoid/anaphylactic reactions; hypocalcemia (preexisting condition); exacerbation of asthma; increased triglycerides

- OVERDOSAGE

-

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

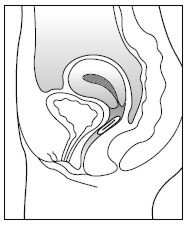

One ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) is to be inserted as deeply as possible into the upper one-third of the vaginal vault. The ring is to remain in place continuously for three months, after which it is to be removed and, if appropriate, replaced by a new ring. The need to continue treatment should be assessed at 3 or 6 month intervals.

Should the ring be removed or fall out at any time during the 90-day treatment period, the ring should be rinsed in lukewarm water and re-inserted by the patient, or, if necessary, by a physician or nurse.

Retention of the ring for greater than 90 days does not represent overdosage but will result in progressively greater underdosage with the attendant risk of loss of efficacy and increasing risk of vaginal infections and/or erosions.

Instructions for Use

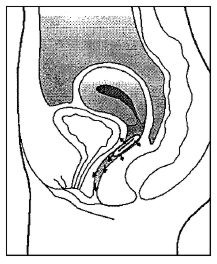

ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) insertion

The ring should be pressed into an oval and inserted into the upper third of the vaginal vault. The exact position is not critical. When ESTRING is in place, the patient should not feel anything. If the patient feels discomfort, ESTRING is probably not far enough inside. Gently push ESTRING further into the vagina.

ESTRING use

ESTRING should be left in place continuously for 90 days and then, if continuation of therapy is deemed appropriate, replaced by a new ESTRING.

The patient should not feel ESTRING when it is in place and it should not interfere with sexual intercourse. Straining at defecation may make ESTRING move down in the lower part of the vagina. If so, it may be pushed up again with a finger.

If ESTRING is expelled totally from the vagina, it should be rinsed in lukewarm water and reinserted by the patient (or doctor/nurse if necessary).

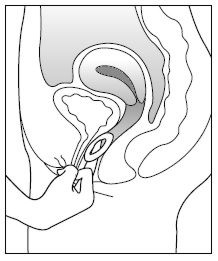

ESTRING removal

ESTRING may be removed by hooking a finger through the ring and pulling it out.

For patient instructions, see Patient Information.

-

HOW SUPPLIED

Each ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) is individually packaged in a heat-sealed rectangular pouch consisting of three layers, from outside to inside: polyester, aluminum foil, and low density polyethylene, respectively. The pouch is provided with a tear-off notch on one side.

NDC: 0013-2150-36 ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) 2 mg - available in single packs.

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

PATIENT INFORMATION

ESTRING

(estradiol vaginal ring)Read this PATIENT INFORMATION before you start using ESTRING and read the patient information each time you refill your ESTRING prescription. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your menopausal symptoms and their treatment.

-

BOXED WARNING

(What is this?)

What is the most important information I should know about ESTRING (an estrogen hormone)?

- Estrogens increase the chance of getting cancer of the uterus.

Report any unusual vaginal bleeding right away while you are using ESTRING. Vaginal bleeding after menopause may be a warning sign of cancer of the uterine (womb). Your healthcare provider should check any unusual vaginal bleeding to find out the cause.

- Do not use estrogens with or without progestins to prevent heart disease, heart attacks, strokes, or dementia.

Using estrogens with or without progestins may increase your chance of getting heart attacks, strokes, breast cancer, and blood clots. Using estrogens with or without progestins may increase your risk of dementia, based on a study of women age 65 years or older.

You and your healthcare provider should talk regularly about whether you still need treatment with ESTRING.

-

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

What is ESTRING?

ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) is an off-white, soft, flexible ring with a center that contains 2 mg of estradiol (an estrogen hormone). ESTRING releases estradiol into the vagina in a consistent, stable manner for 90 days. The soft, flexible ring is placed in the upper third of the vagina (by the physician or the patient). ESTRING should be removed after 90 days of continuous use. If continuation of therapy is indicated, the flexible ring should be replaced.

What is ESTRING used for?

ESTRING is used after menopause to:

- Treat moderate to severe itching, burning, and dryness in or around the vagina.

You and your healthcare provider should talk regularly about whether you still need treatment with ESTRING to control these problems.

Who should not use ESTRING?

Do not start using ESTRING if you:

- Have unusual vaginal bleeding

-

Currently have or have had certain cancers

Estrogens may increase the chance of getting certain types of cancers, including cancer of the breast or uterus. If you have or had cancer, talk with your healthcare provider about whether you should use ESTRING.

- Had a stroke or heart attack in the past year

- Currently have or have had blood clots

- Currently have or have had liver problems

-

Are allergic to any of the ingredients in ESTRING

See the list of ingredients in ESTRING at the end of this leaflet.

- Think you may be pregnant

Tell your healthcare provider:

-

If you are breastfeeding

The hormone in ESTRING can pass into your breast milk.

-

About all of your medical problems

Your healthcare provider may need to check you more carefully if you have certain conditions, such as asthma (wheezing), epilepsy (seizures), migraine, endometriosis, lupus, or problems with your heart, liver, thyroid, kidneys, or have high calcium levels in your blood.

-

About all the medicines you take

This includes prescription and nonprescription medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements. Some medicines may affect how ESTRING works. ESTRING may also affect how your other medicines work.

-

If you are going to have surgery or will be on bed rest

You may need to stop taking estrogens.

How should I use ESTRING?

ESTRING is a local estrogen therapy designed to relieve itching, burning and dryness in and around the vagina . ESTRING PROVIDES RELIEF OF LOCAL SYMPTOMS OF MENOPAUSE ONLY.

Estrogens should be used only as long as needed. You and your healthcare provider should talk regularly (for example, every 3 to 6 months) about whether you still need treatment with ESTRING.

ESTRING INSERTION

ESTRING can be inserted and removed by you or your doctor or healthcare provider. To insert ESTRING yourself, choose the position that is most comfortable for you: standing with one leg up, squatting, or lying down.

- After washing and drying your hands, remove ESTRING from its pouch using the tear-off notch on the side. (Since the ring becomes slippery when wet, be sure your hands are dry before handling it.)

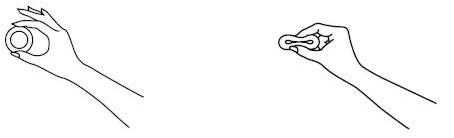

- Hold ESTRING between your thumb and index finger and press the opposite sides of the ring together as shown.

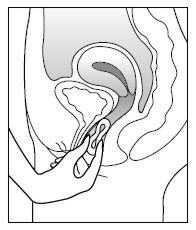

- Gently push the compressed ring into your vagina as far as you can.

ESTRING PLACEMENT

The exact position of ESTRING is not critical, as long as it is placed in the upper third of the vagina.

When ESTRING is in place, you should not feel anything. If you feel uncomfortable, ESTRING is probably not far enough inside. Use your finger to gently push ESTRING further into your vagina.

There is no danger of ESTRING being pushed too far up in the vagina or getting lost. ESTRING can only be inserted as far as the end of the vagina, where the cervix (the narrow, lower end of the uterus) will block ESTRING from going any further (see diagram of Female Anatomy).

ESTRING USE

Once inserted, ESTRING should remain in place in the vagina for 90 days.

Most women and their partners experience no discomfort with ESTRING in place during intercourse, so it is NOT necessary that the ring be removed. If ESTRING should cause you or your partner any discomfort, you may remove it prior to intercourse (see ESTRING Removal, below). Be sure to reinsert ESTRING as soon as possible afterwards.

ESTRING may slide down into the lower part of the vagina as a result of the abdominal pressure or straining that sometimes accompanies constipation. If this should happen, gently guide ESTRING back into place with your finger.

There have been rare reports of ESTRING falling out in some women following intense straining or coughing. If this should occur, simply wash ESTRING with lukewarm (NOT hot) water and reinsert it.

ESTRING DRUG DELIVERY

Once in the vagina, ESTRING begins to release estradiol immediately. ESTRING will continue to release a low, continuous dose of estradiol for the full 90 days it remains in place.

It will take about 2 to 3 weeks to restore the tissue of the vagina and urinary tract to a healthier condition and to feel the full effect of ESTRING in relieving vaginal and urinary symptoms. If your symptoms persist for more than a few weeks after beginning ESTRING therapy, contact your doctor or healthcare provider.

One of the most frequently reported effects associated with the use of ESTRING is an increase in vaginal secretions. These secretions are like those that occur normally prior to menopause and indicate that ESTRING is working. However, if the secretions are associated with a bad odor or vaginal itching or discomfort, be sure to contact your doctor or healthcare provider.

After 90 days there will no longer be enough estradiol in the ring to maintain its full effect in relieving your vaginal or urinary symptoms. ESTRING should be removed at that time and replaced with a new ESTRING, if your doctor determines that you need to continue your therapy.

To remove ESTRING:

- Wash and dry your hands thoroughly.

- Assume a comfortable position, either standing with one leg up, squatting, or lying down.

- Loop your finger through the ring and gently pull it out.

- Discard the used ring in a waste receptacle. (Do not flush ESTRING.)

If you have any additional questions about removing ESTRING, contact your doctor or healthcare provider.

What are the possible side effects of ESTRING?

A few cases of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) have been reported in women using vaginal rings. Toxic shock syndrome is a rare but serious illness caused by a bacterial infection. If you have fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pain, dizziness, faintness, or a sunburn-like rash on face and body, remove ESTRING and contact your healthcare provider. A few cases of the vaginal ring becoming attached to the vaginal wall, making ring removal difficult, have been reported.

The most frequently reported side effect with ESTRING use is increased vaginal secretions. Many of these vaginal secretions are like those that occur normally prior to menopause and indicate that ESTRING is working. Vaginal secretions that are associated with a bad odor, vaginal itching, or other signs of vaginal infection are NOT normal and may indicate a risk or a cause for concern. Other side effects may include vaginal discomfort, abdominal pain, or genital itching.

What are the possible side effects of estrogens ?

Side effects are grouped by how serious they are and how often they happen when you are treated.

Serious but less common side effects include:

- Breast cancer

- Cancer of the uterus

- Stroke

- Heart attack

- Blood clots

- Dementia

- Gallbladder disease

- Ovarian cancer

- High blood pressure

- Liver problems

- High blood sugar

- Enlargement of benign tumors of the uterus ("fibroids")

Some of the warning signs of these serious side effects include:

- Breast lumps

- Unusual vaginal bleeding

- Dizziness and faintness

- Changes in speech

- Severe headaches

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Pains in your legs

- Changes in vision

- Vomiting

- Yellowing of the skin, eyes or nail beds

Call your healthcare provider right away if you get any of these warning signs, or any other unusual symptom that concerns you.

Less serious but common side effects include:

- Headache

- Breast pain

- Irregular vaginal bleeding or spotting

- Stomach/abdominal cramps, bloating

- Nausea and vomiting

- Hair loss

- Fluid retention

- Vaginal yeast infection

These are not all the possible side effects of estrogens. For more information, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist.

What can I do to lower my chances of getting a serious side effect with ESTRING?

- Follow carefully the instructions for use.

- Talk with your healthcare provider regularly about whether you should continue using ESTRING.

- See your healthcare provider right away if you get vaginal bleeding while using ESTRING.

- If you have fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pain, dizziness, faintness, or a sunburn-like rash on face and body, remove ESTRING and contact your healthcare provider.

- Contact your healthcare provider if you have difficulty removing the vaginal ring.

- Have a breast exam and mammogram (breast X-ray) every year unless your healthcare provider tells you something else. If members of your family have had breast cancer or if you have ever had breast lumps or an abnormal mammogram, you may need to have breast examinations more often.

- If you have high blood pressure, high cholesterol (fat in the blood), diabetes, are overweight, or if you use tobacco, you may have higher chances for getting heart disease. Ask your healthcare provider for ways to lower your chances for getting heart disease.

General information about safe and effective use of ESTRING

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for conditions that are not mentioned in patient information leaflets. Do not use ESTRING for conditions for which it was not prescribed. Do not give ESTRING to other people, even if they have the same symptoms you have. It may harm them.

Keep ESTRING out of the reach of children.

This leaflet provides a summary of the most important information about ESTRING. If you would like more information, talk with your healthcare provider or pharmacist. You can ask for information about ESTRING that is written for health professionals. You can get more information by calling the toll free number 1-888-691-6813.

What are the ingredients in ESTRING?

ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring) is a slightly opaque ring with a whitish core containing a drug reservoir of 2 mg estradiol (an estrogen hormone). Estradiol, silicone polymers and barium sulfate are combined to form the ring.

Storage: Store at controlled room temperature 15° to 30° C (59° to 86° F).

LAB-0087-4.0

August 2008

-

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 2 mg Ring Carton

NDC: 63539-021-01

PROFESSIONAL SAMPLE – NOT FOR SALE

Rx onlyEstring®

estradiol vaginal ring2 mg

1 unit

-

INGREDIENTS AND APPEARANCE

ESTRING

estradiol ringProduct Information Product Type HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG Item Code (Source) NDC: 63539-021 Route of Administration VAGINAL Active Ingredient/Active Moiety Ingredient Name Basis of Strength Strength ESTRADIOL (UNII: 4TI98Z838E) (ESTRADIOL - UNII:4TI98Z838E) ESTRADIOL 2 mg Inactive Ingredients Ingredient Name Strength BARIUM SULFATE (UNII: 25BB7EKE2E) Packaging # Item Code Package Description Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date 1 NDC: 63539-021-01 1 in 1 POUCH; Type 4: Device Coated/Impregnated/Otherwise Combined with Drug 04/26/1996 Marketing Information Marketing Category Application Number or Monograph Citation Marketing Start Date Marketing End Date NDA NDA020472 04/26/1996 Labeler - U.S. Pharmaceuticals (829076905)

Trademark Results [Estring]

Mark Image Registration | Serial | Company Trademark Application Date |

|---|---|

ESTRING 74496606 2086164 Live/Registered |

PFIZER HEALTH AB 1994-03-03 |

ESTRING 74198624 not registered Dead/Abandoned |

Kabi Pharmacia AB 1991-08-27 |

© 2026 FDA.report

This site is not affiliated with or endorsed by the FDA.