GABACAINE- gabapentin, lidocaine kit

Gabacaine by

Drug Labeling and Warnings

Gabacaine by is a Prescription medication manufactured, distributed, or labeled by PureTek Corporation, Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc.. Drug facts, warnings, and ingredients follow.

Drug Details [pdf]

-

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use GABAPENTIN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for GABAPENTIN.

GABAPENTIN capsules, for oral use

GABAPENTIN tablets, for oral use

Initial U.S. Approval: 1993

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

-

Postherpetic Neuralgia (2.1)

- Dose can be titrated up as needed to a dose of 1800 mg/day

- Day 1: Single 300 mg dose

- Day 2: 600 mg/day (i.e., 300 mg two times a day)

- Day 3: 900 mg/day (i.e., 300 mg three times a day)

-

Epilepsy with Partial Onset Seizures (2.2)

- Patients 12 years of age and older: starting dose is 300 mg three times daily; may be titrated up to 600 mg three times daily

- Patients 3 to 11 years of age: starting dose range is 10 to 15 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses; recommended dose in patients 3 to 4 years of age is 40 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses; the recommended dose in patients 5 to 11 years of age is 25 to 35 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses. The recommended dose is reached by upward titration over a period of approximately 3 days

- Dose should be adjusted in patients with reduced renal function (2.3, 2.4)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Known hypersensitivity to gabapentin or its ingredients (4)

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (Multiorgan hypersensitivity): Discontinue if alternative etiology is not established (5.1)

- Anaphylaxis and Angioedema: Discontinue and evaluate patient immediately (5.2)

- Driving impairment; Somnolence/Sedation and Dizziness: Warn patients not to drive until they have gained sufficient experience to assess whether their ability to drive or operate heavy machinery will be impaired (5.3, 5.4)

- Increased seizure frequency may occur in patients with seizure disorders if gabapentin is abruptly discontinued (5.5)

- Suicidal Behavior and Ideation: Monitor for suicidal thoughts/behavior (5.6)

- Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions in Children 3 to 12 Years of Age: Monitor for such events (5.7)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥8% and at least twice that for placebo) were:

- Postherpetic neuralgia: Dizziness, somnolence, and peripheral edema (6.1)

- Epilepsy in patients >12 years of age: Somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, and nystagmus (6.1)

- Epilepsy in patients 3 to 12 years of age: Viral infection, fever, nausea and/or vomiting, somnolence, and hostility (6.1)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact ScieGen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. at 1-855-724-3436 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

- Pregnancy: Based on animal data, may cause fetal harm (8.1)

See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and Medication Guide.

Revised: 5/2019

-

Postherpetic Neuralgia (2.1)

-

Table of Contents

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Dosage for Postherpetic Neuralgia

2.2 Dosage for Epilepsy with Partial Onset Seizures

2.3 Dosage Adjustment in Patients with Renal Impairment

2.4 Dosage in Elderly

2.5 Administration Information

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity

5.2 Anaphylaxis and Angioedema

5.3 Effects on Driving and Operating Heavy Machinery

5.4 Somnolence/Sedation and Dizziness

5.5 Withdrawal Precipitated Seizure, Status Epilepticus

5.6 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

5.7 Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions (Pediatric Patients 3 to 12 Years of Age)

5.8 Tumorigenic Potential

5.9 Sudden and Unexplained Death in Patients with Epilepsy

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Other Antiepileptic Drugs

7.2 Opioids

7.3 Maalox® (aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide)

7.4 Drug/Laboratory Test Interactions

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.2 Lactation

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

8.6 Renal Impairment

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

9.2 Abuse

9.3 Dependence

10 OVERDOSAGE

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Postherpetic Neuralgia

14.2 Epilepsy for Partial Onset Seizures (Adjunctive Therapy)

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetics

- * Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

- 1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

-

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Dosage for Postherpetic Neuralgia

In adults with postherpetic neuralgia, gabapentin may be initiated on Day 1 as a single 300 mg dose, on Day 2 as 600 mg/day (300 mg two times a day), and on Day 3 as 900 mg/day (300 mg three times a day). The dose can subsequently be titrated up as needed for pain relief to a dose of 1800 mg/day (600 mg three times a day). In clinical studies, efficacy was demonstrated over a range of doses from 1800 mg/day to 3600 mg/day with comparable effects across the dose range; however, in these clinical studies, the additional benefit of using doses greater than 1800 mg/day was not demonstrated.

2.2 Dosage for Epilepsy with Partial Onset Seizures

Patients 12 years of age and above

The starting dose is 300 mg three times a day. The recommended maintenance dose of gabapentin is 300 mg to 600 mg three times a day. Dosages up to 2,400 mg/day have been well tolerated in long-term clinical studies. Doses of 3,600 mg/day have also been administered to a small number of patients for a relatively short duration, and have been well tolerated. Administer gabapentin three times a day using 300 mg or 400 mg capsules, or 600 mg or 800 mg tablets. The maximum time between doses should not exceed 12 hours.

Pediatric Patients Age 3 to 11 years

The starting dose range is 10 mg/kg/day to 15 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses, and the recommended maintenance dose reached by upward titration over a period of approximately 3 days. The recommended maintenance dose of gabapentin in patients 3 to 4 years of age is 40 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses. The recommended maintenance dose of gabapentin in patients 5 to 11 years of age is 25 mg/kg/day to 35 mg/kg/day, given in three divided doses. Gabapentin may be administered as the oral solution, capsule, or tablet, or using combinations of these formulations. Dosages up to 50 mg/kg/day have been well tolerated in a long-term clinical study. The maximum time interval between doses should not exceed 12 hours.

2.3 Dosage Adjustment in Patients with Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustment in patients 12 years of age and older with renal impairment or undergoing hemodialysis is recommended, as follows (see dosing recommendations above for effective doses in each indication):

TABLE 1. Gabapentin Dosage Based on Renal Function

Renal Function

Creatinine Clearance

(mL/min)

Total Daily

Dose Range

(mg/day)

Dose Regimen

(mg)

≥ 60

900 to 3,600

300 TID

400 TID

600 TID

800 TID

1,200 TID

> 30 to 59

400 to 1,400

200 BID

300 BID

400 BID

500 BID

700 BID

> 15 to 29

200 to 700

200 QD

300 QD

400 QD

500 QD

700 QD

15a

100 to 300

100 QD

125 QD

150 QD

200 QD

300 QD

Post-Hemodialysis Supplemental Dose (mg)b

Hemodialysis

125 b

150b

200b

250b

350b

TID = Three times a day; BID = Two times a day; QD = Single daily dose

a For patients with creatinine clearance <15 mL/min, reduce daily dose in proportion to creatinine clearance (e.g., patients with a creatinine clearance of 7.5 mL/min should receive one-half the daily dose that patients with a creatinine clearance of 15 mL/min receive).

b Patients on hemodialysis should receive maintenance doses based on estimates of creatinine clearance as indicated in the upper portion of the table and a supplemental post-hemodialysis dose administered after each 4 hours of hemodialysis as indicated in the lower portion of the table.

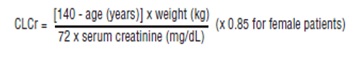

Creatinine clearance (CLCr) is difficult to measure in outpatients. In patients with stable renal function, creatinine clearance can be reasonably well estimated using the equation of Cockcroft and Gault:

The use of gabapentin in patients less than 12 years of age with compromised renal function has not been studied.

2.4 Dosage in Elderly

Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, care should be taken in dose selection, and dose should be adjusted based on creatinine clearance values in these patients.

2.5 Administration Information

Administer gabapentin orally with or without food. Gabapentin capsules should be swallowed whole with water. Inform patients that, should they divide the scored 600 mg or 800 mg gabapentin tablet in order to administer a half-tablet, they should take the unused half-tablet as the next dose. Half tablets not used within 28 days of dividing the scored tablet should be discarded. If the gabapentin dose is reduced, discontinued, or substituted with an alternative medication, this should be done gradually over a minimum of 1 week (a longer period may be needed at the discretion of the prescriber).

-

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Capsules:

- 100 mg: White to off-white powder filled in size “3” hard gelatin capsules with opaque white colored cap and opaque white colored body imprinted SG on cap and 179 on body with black ink.

- 300 mg: White to off-white powder filled in size “1” hard gelatin capsules with opaque yellow colored cap and opaque yellow colored body imprinted SG on cap and 180 on body with black ink.

- 400 mg: White to off-white powder filled in size “0” hard gelatin capsules with opaque orange colored cap and opaque orange colored body imprinted SG on cap and 181 on body with black ink.

Tablets:

- 600 mg: White to off white, modified capsule shape, biconvex, film-coated functional scored tablets debossed with “SG” on one side and “177” on other side with bisect line on both sides.

- 800 mg: White to off white, modified capsule shape, biconvex, film-coated functional scored tablets debossed with “SG” on one side and “178” on other side with bisect line on both sides.

- 4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

-

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), also known as multiorgan hypersensitivity, has occurred with gabapentin. Some of these reactions have been fatal or life-threatening. DRESS typically, although not exclusively, presents with fever, rash, and/or lymphadenopathy, in association with other organ system involvement, such as hepatitis, nephritis, hematological abnormalities, myocarditis, or myositis sometimes resembling an acute viral infection. Eosinophilia is often present. This disorder is variable in its expression, and other organ systems not noted here may be involved.

It is important to note that early manifestations of hypersensitivity, such as fever or lymphadenopathy, may be present even though rash is not evident. If such signs or symptoms are present, the patient should be evaluated immediately. Gabapentin should be discontinued if an alternative etiology for the signs or symptoms cannot be established.

5.2 Anaphylaxis and Angioedema

Gabapentin can cause anaphylaxis and angioedema after the first dose or at any time during treatment. Signs and symptoms in reported cases have included difficulty breathing, swelling of the lips, throat, and tongue, and hypotension requiring emergency treatment. Patients should be instructed to discontinue gabapentin and seek immediate medical care should they experience signs or symptoms of anaphylaxis or angioedema.

5.3 Effects on Driving and Operating Heavy Machinery

Patients taking gabapentin should not drive until they have gained sufficient experience to assess whether gabapentin impairs their ability to drive. Driving performance studies conducted with a prodrug of gabapentin (gabapentin enacarbil tablet, extended release) indicate that gabapentin may cause significant driving impairment. Prescribers and patients should be aware that patients’ ability to assess their own driving competence, as well as their ability to assess the degree of somnolence caused by gabapentin, can be imperfect. The duration of driving impairment after starting therapy with gabapentin is unknown. Whether the impairment is related to somnolence [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)] or other effects of gabapentin is unknown.

Moreover, because gabapentin causes somnolence and dizziness [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)], patients should be advised not to operate complex machinery until they have gained sufficient experience on gabapentin to assess whether gabapentin impairs their ability to perform such tasks.

5.4 Somnolence/Sedation and Dizziness

During the controlled epilepsy trials in patients older than 12 years of age receiving doses of gabapentin up to 1,800 mg daily, somnolence, dizziness, and ataxia were reported at a greater rate in patients receiving gabapentin compared to placebo: i.e., 19% in drug versus 9% in placebo for somnolence, 17% in drug versus 7% in placebo for dizziness, and 13% in drug versus 6% in placebo for ataxia. In these trials somnolence, ataxia and fatigue were common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation of gabapentin in patients older than 12 years of age, with 1.2%, 0.8% and 0.6% discontinuing for these events, respectively.

During the controlled trials in patients with post-herpetic neuralgia, somnolence and dizziness were reported at a greater rate compared to placebo in patients receiving gabapentin, in dosages up to 3600 mg per day: i.e., 21% in gabapentin-treated patients versus 5% in placebo-treated patients for somnolence and 28% in Gabapentin-treated patients versus 8% in placebo-treated patients for dizziness. Dizziness and somnolence were among the most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation of gabapentin.

Patients should be carefully observed for signs of central nervous system (CNS) depression, such as somnolence and sedation, when gabapentin is used with other drugs with sedative properties because of potential synergy. In addition, patients who require concomitant treatment with morphine may experience increases in gabapentin concentrations and may require dose adjustment [see Drug Interactions (7.2)].

5.5 Withdrawal Precipitated Seizure, Status Epilepticus

Antiepileptic drugs should not be abruptly discontinued because of the possibility of increasing seizure frequency.

In the placebo-controlled epilepsy studies in patients >12 years of age, the incidence of status epilepticus in patients receiving gabapentin was 0.6% (3 of 543) versus 0.5% in patients receiving placebo (2 of 378). Among the 2,074 patients >12 years of age treated with gabapentin across all epilepsy studies (controlled and uncontrolled), 31 (1.5%) had status epilepticus. Of these, 14 patients had no prior history of status epilepticus either before treatment or while on other medications. Because adequate historical data are not available, it is impossible to say whether or not treatment with gabapentin is associated with a higher or lower rate of status epilepticus than would be expected to occur in a similar population not treated with gabapentin.

5.6 Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including gabapentin, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Pooled analyses of 199 placebo-controlled clinical trials (mono-and adjunctive therapy) of 11 different AEDs showed that patients randomized to one of the AEDs had approximately twice the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 1.8, 95% CI:1.2, 2.7) of suicidal thinking or behavior compared to patients randomized to placebo. In these trials, which had a median treatment duration of 12 weeks, the estimated incidence rate of suicidal behavior or ideation among 27,863 AED-treated patients was 0.43%, compared to 0.24% among 16,029 placebo-treated patients, representing an increase of approximately one case of suicidal thinking or behavior for every 530 patients treated. There were four suicides in drug-treated patients in the trials and none in placebo-treated patients, but the number is too small to allow any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

The increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with AEDs was observed as early as one week after starting drug treatment with AEDs and persisted for the duration of treatment assessed. Because most trials included in the analysis did not extend beyond 24 weeks, the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior beyond 24 weeks could not be assessed.

The risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior was generally consistent among drugs in the data analyzed. The finding of increased risk with AEDs of varying mechanisms of action and across a range of indications suggests that the risk applies to all AEDs used for any indication. The risk did not vary substantially by age (5 to 100 years) in the clinical trials analyzed. Table 2 shows absolute and relative risk by indication for all evaluated AEDs.

Table 2. Risk by Indication for Antiepileptic Drugs in the Pooled Analysis Indication

Placebo Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients

Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients

Relative Risk:Incidence of Events in Drug Patients/Incidence in Placebo Patients

Risk Difference: Additional Drug Patients with Events Per 1,000 Patients

Epilepsy

1.0

3.4

3.5

2.4

Psychiatric

5.7

8.5

1.5

2.9

Other

1.0

1.8

1.9

0.9

Total

2.4

4.3

1.8

1.9

The relative risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior was higher in clinical trials for epilepsy than in clinical trials for psychiatric or other conditions, but the absolute risk differences were similar for the epilepsy and psychiatric indications.

Anyone considering prescribing gabapentin or any other AED must balance the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior with the risk of untreated illness. Epilepsy and many other illnesses for which AEDs are prescribed are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Should suicidal thoughts and behavior emerge during treatment, the prescriber needs to consider whether the emergence of these symptoms in any given patient may be related to the illness being treated.

Patients, their caregivers, and families should be informed that AEDs increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior and should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of the signs and symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Behaviors of concern should be reported immediately to healthcare providers.

5.7 Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions (Pediatric Patients 3 to 12 Years of Age)

Gabapentin use in pediatric patients with epilepsy 3 to 12 years of age is associated with the occurrence of CNS related adverse reactions. The most significant of these can be classified into the following categories: 1) emotional lability (primarily behavioral problems), 2) hostility, including aggressive behaviors, 3) thought disorder, including concentration problems and change in school performance, and 4) hyperkinesia (primarily restlessness and hyperactivity). Among the gabapentin-treated patients, most of the reactions were mild to moderate in intensity.

In controlled clinical epilepsy trials in pediatric patients 3 to 12 years of age, the incidence of these adverse reactions was: emotional lability 6% (gabapentin-treated patients) versus 1.3% (placebo-treated patients); hostility 5.2% versus 1.3%; hyperkinesia 4.7% versus 2.9%; and thought disorder 1.7% versus 0%. One of these reactions, a report of hostility, was considered serious. Discontinuation of gabapentin treatment occurred in 1.3% of patients reporting emotional lability and hyperkinesia and 0.9% of gabapentin-treated patients reporting hostility and thought disorder. One placebo-treated patient (0.4%) withdrew due to emotional lability.

5.8 Tumorigenic Potential

In an oral carcinogenicity study, gabapentin increased the incidence of pancreatic acinar cell tumors in rats [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)]. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown. Clinical experience during gabapentin’s premarketing development provides no direct means to assess its potential for inducing tumors in humans.

In clinical studies in adjunctive therapy in epilepsy comprising 2,085 patient-years of exposure in patients >12 years of age, new tumors were reported in 10 patients (2 breast, 3 brain, 2 lung, 1 adrenal, 1 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 1 endometrial carcinoma in situ), and preexisting tumors worsened in 11 patients (9 brain, 1 breast, 1 prostate) during or up to 2 years following discontinuation of gabapentin. Without knowledge of the background incidence and recurrence in a similar population not treated with gabapentin, it is impossible to know whether the incidence seen in this cohort is or is not affected by treatment.

5.9 Sudden and Unexplained Death in Patients with Epilepsy

During the course of premarketing development of gabapentin, 8 sudden and unexplained deaths were recorded among a cohort of 2,203 epilepsy patients treated (2,103 patient-years of exposure) with gabapentin.

Some of these could represent seizure-related deaths in which the seizure was not observed, e.g., at night. This represents an incidence of 0.0038 deaths per patient-year. Although this rate exceeds that expected in a healthy population matched for age and sex, it is within the range of estimates for the incidence of sudden unexplained deaths in patients with epilepsy not receiving gabapentin (ranging from 0.0005 for the general population of epileptics to 0.003 for a clinical trial population similar to that in the gabapentin program, to 0.005 for patients with refractory epilepsy). Consequently, whether these figures are reassuring or raise further concern depends on comparability of the populations reported upon to the gabapentin cohort and the accuracy of the estimates provided.

-

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are discussed in greater detail in other sections:

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Anaphylaxis and Angioedema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

- Somnolence/Sedation and Dizziness [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Withdrawal Precipitated Seizure, Status Epilepticus [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Suicidal Behavior and Ideation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions (Pediatric Patients 3 to 12 Years of Age) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Sudden and Unexplained Death in Patients with Epilepsy [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Postherpetic Neuralgia

The most common adverse reactions associated with the use of gabapentin in adults, not seen at an equivalent frequency among placebo-treated patients, were dizziness, somnolence, and peripheral edema.

In the 2 controlled trials in postherpetic neuralgia, 16% of the 336 patients who received gabapentin and 9% of the 227 patients who received placebo discontinued treatment because of an adverse reaction. The adverse reactions that most frequently led to withdrawal in gabapentin -treated patients were dizziness, somnolence, and nausea.

Table 3 lists adverse reactions that occurred in at least 1% of gabapentin -treated patients with postherpetic neuralgia participating in placebo-controlled trials and that were numerically more frequent in the gabapentin group than in the placebo group.

Table 3 Adverse Reactions in Pooled Placebo-Controlled Trials in Postherpetic Neuralgia Gabapentin

N=336

%

Placebo

N=227

%

Body as a Whole Asthenia 6 5 Infection 5 4 Accidental injury 3 1 Digestive System Diarrhea 6 3 Dry mouth 5 1 Constipation 4 2 Nausea 4 3 Vomiting 3 2 Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders Peripheral edema 8 2 Weight gain 2 0 Hyperglycemia 1 0 Nervous System Dizziness 28 8 Somnolence 21 5 Ataxia 3 0 Abnormal thinking 3 0 Abnormal gait 2 0 Incoordination 2 0 Respiratory System Pharyngitis 1 0 Special Senses Amblyopiaa 3 1 Conjunctivitis 1 0 Diplopia 1 0 Otitis media 1 0 a Reported as blurred vision

Other reactions in more than 1% of patients but equally or more frequent in the placebo group included pain, tremor, neuralgia, back pain, dyspepsia, dyspnea, and flu syndrome.

There were no clinically important differences between men and women in the types and incidence of adverse reactions. Because there were few patients whose race was reported as other than white, there are insufficient data to support a statement regarding the distribution of adverse reactions by race.

Epilepsy with Partial Onset Seizures (Adjunctive Therapy)

The most common adverse reactions with gabapentin in combination with other antiepileptic drugs in patients >12 years of age, not seen at an equivalent frequency among placebo-treated patients, were somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, and nystagmus. The most common adverse reactions with gabapentin in combination with other antiepileptic drugs in pediatric patients 3 to 12 years of age, not seen at an equal frequency among placebo-treated patients, were viral infection, fever, nausea and/or vomiting, somnolence, and hostility [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]. Approximately 7% of the 2,074 patients >12 years of age and approximately 7% of the 449 pediatric patients 3 to 12 years of age who received gabapentin in premarketing clinical trials discontinued treatment because of an adverse reaction.

The adverse reactions most commonly associated with withdrawal in patients >12 years of age were somnolence (1.2%), ataxia (0.8%), fatigue (0.6%), nausea and/or vomiting (0.6%), and dizziness (0.6%). The adverse reactions most commonly associated with withdrawal in pediatric patients were emotional lability (1.6%), hostility (1.3%), and hyperkinesia (1.1%).

Table 4 lists adverse reactions that occurred in at least 1% of gabapentin-treated patients >12 years of age with epilepsy participating in placebo-controlled trials and were numerically more common in the gabapentin group. In these studies, either gabapentin or placebo was added to the patient’s current antiepileptic drug therapy

TABLE 4. Adverse Reactions in Pooled Placebo-Controlled Add-On Trials In Epilepsy Patients >12 years of age Gabapentin a

N = 543

%

Placeboa

N = 378

%

Body as a Whole

Fatigue

11

5

Increased Weight

3

2

Back Pain

2

1

Peripheral Edema

2

1

Cardiovascular

Vasodilatation

1

0

Digestive System

Dyspepsia

2

1

Dry Mouth or Throat

2

1

Constipation

2

1

Dental Abnormalities

2

0

Nervous System

Somnolence

19

9

Dizziness

17

7

Ataxia

13

6

Nystagmus

8

4

Tremor

7

3

Dysarthria

2

1

Amnesia

2

0

Depression

2

1

Abnormal Thinking

2

1

Abnormal Coordination

1

0

Respiratory System

Pharyngitis

3

2

Coughing

2

1

Skin and Appendages

Abrasion

1

0

Urogenital System

Impotence

2

1

Special Senses

Diplopia

6

2

Amblyopiab

4

1

aPlus background antiepileptic drug therapy

bAmblyopia was often described as blurred vision.

Among the adverse reactions occurring at an incidence of at least 10% in gabapentin-treated patients, somnolence and ataxia appeared to exhibit a positive dose-response relationship.

The overall incidence of adverse reactions and the types of adverse reactions seen were similar among men and women treated with gabapentin. The incidence of adverse reactions increased slightly with increasing age in patients treated with either gabapentin or placebo. Because only 3% of patients (28/921) in placebo-controlled studies were identified as nonwhite (black or other), there are insufficient data to support a statement regarding the distribution of adverse reactions by race.

Table 5 lists adverse reactions that occurred in at least 2% of gabapentin-treated patients, age 3 to 12 years of age with epilepsy participating in placebo-controlled trials, and which were numerically more common in the gabapentin group.

TABLE 5. Adverse Reactions in a Placebo-Controlled Add-On Trial in Pediatric Epilepsy Patients Age 3 to 12 Years Gabapentin a

N = 119

%

Placeboa

N = 128

%

Body as a Whole

Viral Infection

11

3

Fever

10

3

Increased Weight

3

1

Fatigue

3

2

Digestive System

Nausea and/or Vomiting

8

7

Nervous System

Somnolence

8

5

Hostility

8

2

Emotional Lability

4

2

Dizziness

3

2

Hyperkinesia

3

1

Respiratory System

Bronchitis

3

1

Respiratory Infection

3

1

aPlus background antiepileptic drug therapy

Other reactions in more than 2% of pediatric patients 3 to 12 years of age but equally or more frequent in the placebo group included: pharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, rhinitis, convulsions, diarrhea, anorexia, coughing, and otitis media.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postmarketing use of gabapentin. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Hepatobiliary disorders: jaundice

Investigations: elevated creatine kinase, elevated liver function tests

Metabolism and nutrition disorders: hyponatremia

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders: rhabdomyolysis

Nervous system disorders: movement disorder

Psychiatric disorders: agitation

Reproductive system and breast disorders: breast enlargement, changes in libido, ejaculation disorders and anorgasmia

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: angioedema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)] , erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Adverse reactions following the abrupt discontinuation of gabapentin have also been reported. The most frequently reported reactions were anxiety, insomnia, nausea, pain, and sweating.

-

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Other Antiepileptic Drugs

Gabapentin is not appreciably metabolized nor does it interfere with the metabolism of commonly coadministered antiepileptic drugs [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.2 Opioids

Hydrocodone

Coadministration of gabapentin with hydrocodone decreases hydrocodone exposure [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. The potential for alteration in hydrocodone exposure and effect should be considered when gabapentin is started or discontinued in a patient taking hydrocodone.

Morphine

When gabapentin is administered with morphine, patients should be observed for signs of CNS depression, such as somnolence, sedation and respiratory depression [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.3 Maalox® (aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide)

The mean bioavailability of gabapentin was reduced by about 20% with concomitant use of an antacid (Maalox®) containing magnesium and aluminum hydroxides. It is recommended that gabapentin be taken at least 2 hours following Maalox administration [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.4 Drug/Laboratory Test Interactions

Because false positive readings were reported with the Ames N-Multistix SG® dipstick test for urinary protein when gabapentin was added to other antiepileptic drugs, the more specific sulfosalicylic acid precipitation procedure is recommended to determine the presence of urine protein.

-

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), such as gabapentin, during pregnancy. Encourage women who are taking gabapentin during pregnancy to enroll in the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry by calling the toll free number 1-888-233-2334 or visiting http://www.aedpregnancyregistry.org/.Risk Summary

There are no adequate data on the developmental risks associated with the use of gabapentin in pregnant women. In nonclinical studies in mice, rats, and rabbits, gabapentin was developmentally toxic (increased fetal skeletal and visceral abnormalities, and increased embryofetal mortality) when administered to pregnant animals at doses similar to or lower than those used clinically [see Data].In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2% to 4% and 15% to 20%, respectively. The background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population is unknown.

Data

Animal dataWhen pregnant mice received oral doses of gabapentin (500 mg/kg/day, 1,000 mg/kg/day, or 3,000 mg/kg/day) during the period of organogenesis, embryofetal toxicity (increased incidences of skeletal variations) was observed at the two highest doses. The no-effect dose for embryofetal developmental toxicity in mice (500 mg/kg/day) is less than the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 3,600 mg/kg on a body surface area (mg/m2) basis.

In studies in which rats received oral doses of gabapentin (500 mg/kg/day to 2,000 mg/kg/day) during pregnancy, adverse effect on offspring development (increased incidences of hydroureter and/or hydronephrosis) were observed at all doses. The lowest dose tested is similar to the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

When pregnant rabbits were treated with gabapentin during the period of organogenesis, an increase in embryofetal mortality was observed at all doses tested (60 mg/kg, 300 mg/kg, or 1,500 mg/kg). The lowest dose tested is less than the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis.

In a published study, gabapentin (400 mg/kg/day) was administered by intraperitoneal injection to neonatal mice during the first postnatal week, a period of synaptogenesis in rodents (corresponding to the last trimester of pregnancy in humans). Gabapentin caused a marked decrease in neuronal synapse formation in brains of intact mice and abnormal neuronal synapse formation in a mouse model of synaptic repair. Gabapentin has been shown in vitro to interfere with activity of the α2δ subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels, a receptor involved in neuronal synaptogenesis. The clinical significance of these findings is unknown.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

Gabapentin is secreted in human milk following oral administration. The effects on the breastfed infant and on milk production are unknown. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for gabapentin and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from gabapentin or from the underlying maternal condition.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness of Gabapentin in the management of postherpetic neuralgia in pediatric patients have not been established.

Safety and effectiveness as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial seizures in pediatric patients below the age of 3 years has not been established [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

8.5 Geriatric Use

The total number of patients treated with gabapentin in controlled clinical trials in patients with postherpetic neuralgia was 336, of which 102 (30%) were 65 to 74 years of age, and 168 (50%) were 75 years of age and older. There was a larger treatment effect in patients 75 years of age and older compared to younger patients who received the same dosage. Since gabapentin is almost exclusively eliminated by renal excretion, the larger treatment effect observed in patients ≥75 years may be a consequence of increased gabapentin exposure for a given dose that results from an age-related decrease in renal function. However, other factors cannot be excluded. The types and incidence of adverse reactions were similar across age groups except for peripheral edema and ataxia, which tended to increase in incidence with age.

Clinical studies of gabapentin in epilepsy did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they responded differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

This drug is known to be substantially excreted by the kidney, and the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. Because elderly patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, care should be taken in dose selection, and dose should be adjusted based on creatinine clearance values in these patients [see Dosage and Administration (2.4), Adverse Reactions (6), and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.6 Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustment in adult patients with compromised renal function is necessary [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Pediatric patients with renal insufficiency have not been studied.

Dosage adjustment in patients undergoing hemodialysis is necessary [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

-

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

Gabapentin does not exhibit affinity for benzodiazepine, opiate (mu, delta or kappa), or cannabinoid 1 receptor sites. A small number of postmarketing cases report gabapentin misuse and abuse. These individuals were taking higher than recommended doses of gabapentin for unapproved uses. Most of the individuals described in these reports had a history of poly-substance abuse or used gabapentin to relieve symptoms of withdrawal from other substances. When prescribing gabapentin carefully evaluate patients for a history of drug abuse and observe them for signs and symptoms of gabapentin misuse or abuse (e.g. development of tolerance, self-dose escalation, and drug-seeking behavior).

9.3 Dependence

There are rare postmarketing reports of individuals experiencing withdrawal symptoms shortly after discontinuing higher than recommended doses of gabapentin used to treat illnesses for which the drug is not approved. Such symptoms included agitation, disorientation and confusion after suddenly discontinuing gabapentin that resolved after restarting gabapentin. Most of these individuals had a history of poly-substance abuse or used gabapentin to relieve symptoms of withdrawal from other substances. The dependence and abuse potential of gabapentin has not been evaluated in human studies.

-

10 OVERDOSAGE

A lethal dose of gabapentin was not identified in mice and rats receiving single oral doses as high as 8,000 mg/kg. Signs of acute toxicity in animals included ataxia, labored breathing, ptosis, sedation, hypoactivity, or excitation.

Acute oral overdoses of gabapentin up to 49 grams have been reported. In these cases, double vision, slurred speech, drowsiness, lethargy and diarrhea, were observed. All patients recovered with supportive care. Coma, resolving with dialysis, has been reported in patients with chronic renal failure who were treated with gabapentin.

Gabapentin can be removed by hemodialysis. Although hemodialysis has not been performed in the few overdose cases reported, it may be indicated by the patient’s clinical state or in patients with significant renal impairment.

If overexposure occurs, call your poison control center at 1-800-222-1222.

-

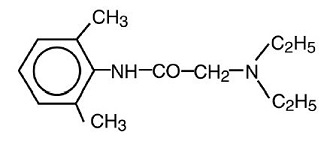

11 DESCRIPTION

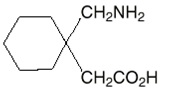

The active ingredient in gabapentin capsules and tablets, USP is gabapentin, which has the chemical name 1-(aminomethyl)cyclohexaneacetic acid.

The molecular formula of gabapentin is C9H17NO2 and the molecular weight is 171.24. The structural formula of gabapentin is:

Gabapentin, USP is a white to off-white crystalline solid with a pKa1 of 4.72±0.10 and a pKa2 of 10.27±0.29. It is freely soluble in water and both basic and acidic aqueous solutions. The log of the partition coefficient is -1.083±0.235 at 25°C temperature.

Each gabapentin capsule contains 100 mg, 300 mg or 400 mg of gabapentin, USP and the following inactive ingredients: pregelatinized starch (maize), and talc. The 100 mg capsule shell contains gelatin, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and titanium dioxide. The 300 mg capsule shell contains gelatin, titanium dioxide, FD&C Red 40, D&C Yellow 10, and sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS). The 400mg capsule shell contains gelatin, titanium dioxide, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), D&C Yellow 10, and FD&C Red 40. The imprinting ink contains shellac, dehydrated alcohol, isopropyl alcohol, butyl alcohol, propylene glycol, strong ammonia solution, black iron oxide, and potassium hydroxide.

Each gabapentin tablet contains 600 mg or 800 mg of gabapentin, USP and the following inactive ingredients: poloxamer 407, mannitol, magnesium stearate, hydroxypropyl cellulose, talc, copovidone, crospovidone, colloidal silicon dioxide and coating agent contains hypromellose, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol and talc.

-

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanism by which gabapentin produces its analgesic and antiepileptic actions are unknown. Gabapentin is structurally related to the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) but has no effect on GABA binding, uptake, or degradation. In vitro studies have shown that gabapentin binds with high-affinity to the α2δ subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels; however, the relationship of this binding to the therapeutic effects of gabapentin is unknown.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

All pharmacological actions following gabapentin administration are due to the activity of the parent compound; gabapentin is not appreciably metabolized in humans.

Oral Bioavailability

Gabapentin bioavailability is not dose proportional; i.e., as dose is increased, bioavailability decreases. Bioavailability of gabapentin is approximately 60%, 47%, 34%, 33%, and 27% following 900 mg/day, 1,200 mg/day, 2,400 mg/day, 3,600 mg/day, and 4,800 mg/day given in 3 divided doses, respectively. Food has only a slight effect on the rate and extent of absorption of gabapentin (14% increase in AUC and Cmax).

Distribution

Less than 3% of gabapentin circulates bound to plasma protein. The apparent volume of distribution of gabapentin after 150 mg intravenous administration is 58±6 L (mean ±SD). In patients with epilepsy, steady-state predose (Cmin) concentrations of gabapentin in cerebrospinal fluid were approximately 20% of the corresponding plasma concentrations.

Elimination

Gabapentin is eliminated from the systemic circulation by renal excretion as unchanged drug. Gabapentin is not appreciably metabolized in humans.

Gabapentin elimination half-life is 5 to 7 hours and is unaltered by dose or following multiple dosing. Gabapentin elimination rate constant, plasma clearance, and renal clearance are directly proportional to creatinine clearance. In elderly patients, and in patients with impaired renal function, gabapentin plasma clearance is reduced. Gabapentin can be removed from plasma by hemodialysis.

Specific Populations

Age

The effect of age was studied in subjects 20 to 80 years of age. Apparent oral clearance (CL/F) of gabapentin decreased as age increased, from about 225 mL/min in those under 30 years of age to about 125 mL/min in those over 70 years of age. Renal clearance (CLr) and CLr adjusted for body surface area also declined with age; however, the decline in the renal clearance of gabapentin with age can largely be explained by the decline in renal function. [see Dosage and Administration (2.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

Gender

Although no formal study has been conducted to compare the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin in men and women, it appears that the pharmacokinetic parameters for males and females are similar and there are no significant gender differences.

Race

Pharmacokinetic differences due to race have not been studied. Because gabapentin is primarily renally excreted and there are no important racial differences in creatinine clearance, pharmacokinetic differences due to race are not expected.

Pediatric

Gabapentin pharmacokinetics were determined in 48 pediatric subjects between the ages of 1 month and 12 years following a dose of approximately 10 mg/kg. Peak plasma concentrations were similar across the entire age group and occurred 2 to 3 hours postdose. In general, pediatric subjects between 1 month and <5 years of age achieved approximately 30% lower exposure (AUC) than that observed in those 5 years of age and older. Accordingly, oral clearance normalized per body weight was higher in the younger children. Apparent oral clearance of gabapentin was directly proportional to creatinine clearance. Gabapentin elimination half-life averaged 4.7 hours and was similar across the age groups studied.

A population pharmacokinetic analysis was performed in 253 pediatric subjects between 1 month and 13 years of age. Patients received 10 to 65 mg/kg/day given three times a day. Apparent oral clearance (CL/F) was directly proportional to creatinine clearance and this relationship was similar following a single dose and at steady state. Higher oral clearance values were observed in children <5 years of age compared to those observed in children 5 years of age and older, when normalized per body weight. The clearance was highly variable in infants <1year of age. The normalized CL/F values observed in pediatric patients 5 years of age and older were consistent with values observed in adults after a single dose. The oral volume of distribution normalized per body weight was constant across the age range.

These pharmacokinetic data indicate that the effective daily dose in pediatric patients with epilepsy ages 3 and 4 years should be 40 mg/kg/day to achieve average plasma concentrations similar to those achieved in patients 5 years of age and older receiving gabapentin at 30 mg/kg/day [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)].

Adult Patients with Renal Impairment

Subjects (N=60) with renal impairment (mean creatinine clearance ranging from 13 to 114 mL/min) were administered single 400 mg oral doses of gabapentin. The mean gabapentin half-life ranged from about 6.5 hours (patients with creatinine clearance >60 mL/min) to 52 hours (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) and gabapentin renal clearance from about 90 mL/min (>60 mL/min group) to about 10 mL/min (<30 mL/min). Mean plasma clearance (CL/F) decreased from approximately 190 mL/min to 20 mL/min [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Use in Specific Populations (8.6)]. Pediatric patients with renal insufficiency have not been studied.

Hemodialysis

In a study in anuric adult subjects (N=11), the apparent elimination half-life of gabapentin on nondialysis days was about 132 hours; during dialysis the apparent half-life of gabapentin was reduced to 3.8 hours. Hemodialysis thus has a significant effect on gabapentin elimination in anuric subjects. [see Dosage and Administration (2.3) and Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Hepatic Disease

Because gabapentin is not metabolized, no study was performed in patients with hepatic impairment.

Drug Interactions

In Vitro Studies

In vitro studies were conducted to investigate the potential of gabapentin to inhibit the major cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4) that mediate drug and xenobiotic metabolism using isoform selective marker substrates and human liver microsomal preparations. Only at the highest concentration tested (171 mcg/mL; 1 mM) was a slight degree of inhibition (14% to 30%) of isoform CYP2A6 observed. No inhibition of any of the other isoforms tested was observed at gabapentin concentrations up to 171 mcg/mL (approximately 15 times the Cmax at 3,600 mg/day).

In Vivo Studies

The drug interaction data described in this section were obtained from studies involving healthy adults and adult patients with epilepsy.

Phenytoin

In a single (400 mg) and multiple dose (400 mg three times a day) study of gabapentin in epileptic patients (N=8) maintained on phenytoin monotherapy for at least 2 months, gabapentin had no effect on the steady-state trough plasma concentrations of phenytoin and phenytoin had no effect on gabapentin pharmacokinetics.

Carbamazepine

Steady-state trough plasma carbamazepine and carbamazepine 10, 11 epoxide concentrations were not affected by concomitant gabapentin (400 mg three times a day; N=12) administration. Likewise, gabapentin pharmacokinetics were unaltered by carbamazepine administration.

Valproic Acid

The mean steady-state trough serum valproic acid concentrations prior to and during concomitant gabapentin administration (400 mg three times a day; N=17) were not different and neither were gabapentin pharmacokinetic parameters affected by valproic acid.

Phenobarbital

Estimates of steady-state pharmacokinetic parameters for phenobarbital or gabapentin (300 mg three times a day; N=12) are identical whether the drugs are administered alone or together.

Naproxen

Coadministration (N=18) of naproxen sodium capsules (250 mg) with gabapentin (125 mg) appears to increase the amount of gabapentin absorbed by 12% to 15%. Gabapentin had no effect on naproxen pharmacokinetic parameters. These doses are lower than the therapeutic doses for both drugs. The magnitude of interaction within the recommended dose ranges of either drug is not known.

Hydrocodone

Coadministration of gabapentin (125 to 500 mg; N=48) decreases hydrocodone (10 mg; N=50) Cmax and AUC values in a dose-dependent manner relative to administration of hydrocodone alone; Cmax and AUC values are 3% to 4% lower, respectively, after administration of 125 mg gabapentin and 21% to 22% lower, respectively, after administration of 500 mg gabapentin. The mechanism for this interaction is unknown. Hydrocodone increases gabapentin AUC values by 14%. The magnitude of interaction at other doses is not known.

Morphine

A literature article reported that when a 60 mg controlled-release morphine capsule was administered 2 hours prior to a 600 mg gabapentin capsule (N=12), mean gabapentin AUC increased by 44% compared to gabapentin administered without morphine. Morphine pharmacokinetic parameter values were not affected by administration of gabapentin 2 hours after morphine. The magnitude of interaction at other doses is not known.

Cimetidine

In the presence of cimetidine at 300 mg four times a day (N=12), the mean apparent oral clearance of gabapentin fell by 14% and creatinine clearance fell by 10%. Thus, cimetidine appeared to alter the renal excretion of both gabapentin and creatinine, an endogenous marker of renal function. This small decrease in excretion of gabapentin by cimetidine is not expected to be of clinical importance. The effect of gabapentin on cimetidine was not evaluated.

Oral Contraceptive

Based on AUC and half-life, multiple-dose pharmacokinetic profiles of norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol following administration of tablets containing 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol were similar with and without coadministration of gabapentin (400 mg three times a day; N=13). The Cmax of norethindrone was 13% higher when it was coadministered with gabapentin; this interaction is not expected to be of clinical importance.

Antacid (Maalox®) (aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide)

Antacid (Maalox®) containing magnesium and aluminum hydroxides reduced the mean bioavailability of gabapentin (N=16) by about 20%. This decrease in bioavailability was about 10% when gabapentin was administered 2 hours after Maalox.

Probenecid

Probenecid is a blocker of renal tubular secretion. Gabapentin pharmacokinetic parameters without and with probenecid were comparable. This indicates that gabapentin does not undergo renal tubular secretion by the pathway that is blocked by probenecid.

-

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Gabapentin was administered orally to mice and rats in 2-year carcinogenicity studies. No evidence of drug-related carcinogenicity was observed in mice treated at doses up to 2,000 mg/kg/day. At 2,000 mg/kg, the plasma gabapentin exposure (AUC) in mice was approximately 2 times that in humans at the MRHD of 3,600 mg/day. In rats, increases in the incidence of pancreatic acinar cell adenoma and carcinoma were found in male rats receiving the highest dose (2,000 mg/kg), but not at doses of 250 or 1,000 mg/kg/day. At 1,000 mg/kg, the plasma gabapentin exposure (AUC) in rats was approximately 5 times that in humans at the MRHD.

Studies designed to investigate the mechanism of gabapentin-induced pancreatic carcinogenesis in rats indicate that gabapentin stimulates DNA synthesis in rat pancreatic acinar cells in vitro and, thus, may be acting as a tumor promoter by enhancing mitogenic activity. It is not known whether gabapentin has the ability to increase cell proliferation in other cell types or in other species, including humans.

Mutagenesis

Gabapentin did not demonstrate mutagenic or genotoxic potential in in vitro (Ames test, HGPRT forward mutation assay in Chinese hamster lung cells) and in vivo (chromosomal aberration and micronucleus test in Chinese hamster bone marrow, mouse micronucleus, unscheduled DNA synthesis in rat hepatocytes) assays.Impairment of Fertility

No adverse effects on fertility or reproduction were observed in rats at doses up to 2,000 mg/kg. At 2,000 mg/kg, the plasma gabapentin exposure (AUC) in rats is approximately 8 times that in humans at the MRHD. -

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Postherpetic Neuralgia

Gabapentin was evaluated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population consisted of a total of 563 patients with pain for more than 3 months after healing of the herpes zoster skin rash (Table 6).

TABLE 6. Controlled PHN Studies: Duration, Dosages, and Number of Patients Study Study Duration Gabapentin

(mg/day)a

Target DosePatients Receiving Gabapentin Patients Receiving Placebo 1 8 weeks 3600 113 116 2 7 weeks 1800, 2400 223 111 Total 336 227 aGiven in 3 divided doses (TID)

Each study included a 7- or 8-week double-blind phase (3 or 4 weeks of titration and 4 weeks of fixed dose). Patients initiated treatment with titration to a maximum of 900 mg/day gabapentin over 3 days. Dosages were then to be titrated in 600 to 1200 mg/day increments at 3- to 7-day intervals to the target dose over 3 to 4 weeks. Patients recorded their pain in a daily diary using an 11-point numeric pain rating scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). A mean pain score during baseline of at least 4 was required for randomization. Analyses were conducted using the ITT population (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication).

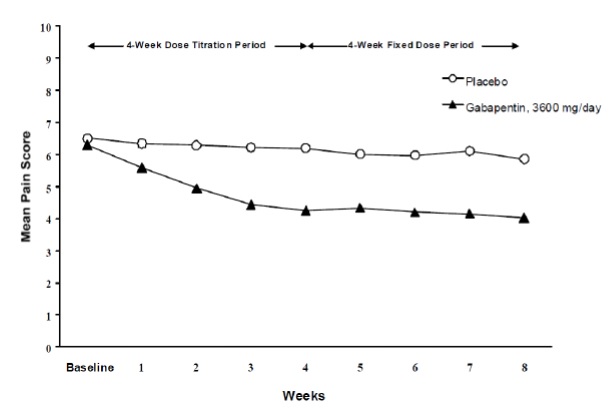

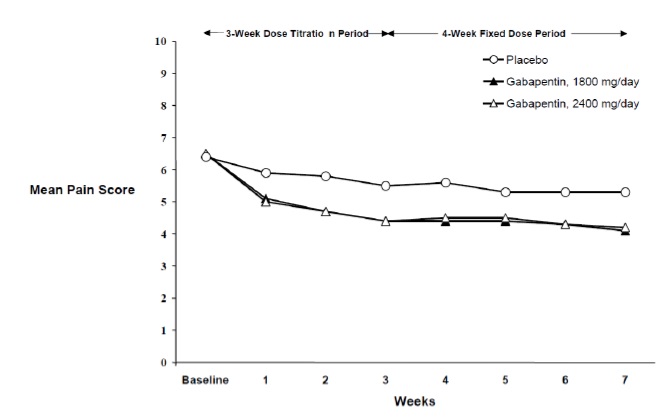

Both studies demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo at all doses tested.

The reduction in weekly mean pain scores was seen by Week 1 in both studies, and were maintained to the end of treatment. Comparable treatment effects were observed in all active treatment arms. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling provided confirmatory evidence of efficacy across all doses. Figures 1 and 2 show pain intensity scores over time for Studies 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Weekly Mean Pain Scores (Observed Cases in ITT Population): Study 1

Figure 2. Weekly Mean Pain Scores (Observed Cases in ITT Population): Study 2

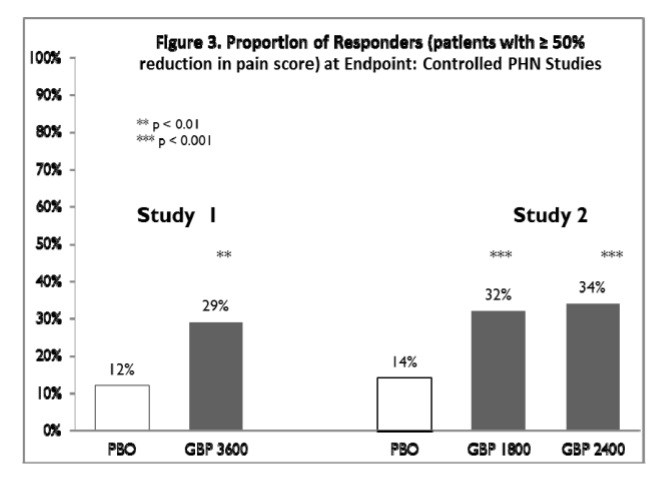

The proportion of responders (those patients reporting at least 50% improvement in endpoint pain score compared to baseline) was calculated for each study (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion of Responders (patients with ≥ 50% reduction in pain score) at Endpoint: Controlled PHN Studies

14.2 Epilepsy for Partial Onset Seizures (Adjunctive Therapy)

The effectiveness of gabapentin as adjunctive therapy (added to other antiepileptic drugs) was established in multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group clinical trials in adult and pediatric patients (3 years and older) with refractory partial seizures.

Evidence of effectiveness was obtained in three trials conducted in 705 patients (age 12 years and above) and one trial conducted in 247 pediatric patients (3 to 12 years of age). The patients enrolled had a history of at least 4 partial seizures per month in spite of receiving one or more antiepileptic drugs at therapeutic levels and were observed on their established antiepileptic drug regimen during a 12-week baseline period (6 weeks in the study of pediatric patients). In patients continuing to have at least 2 (or 4 in some studies) seizures per month, gabapentin or placebo was then added on to the existing therapy during a 12-week treatment period. Effectiveness was assessed primarily on the basis of the percent of patients with a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency from baseline to treatment (the “responder rate”) and a derived measure called response ratio, a measure of change defined as (T -B)/(T + B), in which B is the patient’s baseline seizure frequency and T is the patient’s seizure frequency during treatment. Response ratio is distributed within the range -1 to +1. A zero value indicates no change while complete elimination of seizures would give a value of -1; increased seizure rates would give positive values. A response ratio of -0.33 corresponds to a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. The results given below are for all partial seizures in the intent-to-treat (all patients who received any doses of treatment) population in each study, unless otherwise indicated.

One study compared gabapentin 1,200 mg/day, in three divided doses with placebo. Responder rate was 23% (14/61) in the gabapentin group and 9% (6/66) in the placebo group; the difference between groups was statistically significant. Response ratio was also better in the gabapentin group (-0.199) than in the placebo group (-0.044), a difference that also achieved statistical significance.

A second study compared primarily gabapentin 1,200 mg/day, in three divided doses (N=101), with placebo (N=98). Additional smaller gabapentin dosage groups (600 mg/day, N=53; 1,800 mg/day, N=54) were also studied for information regarding dose response. Responder rate was higher in the gabapentin 1,200 mg/day group (16%) than in the placebo group (8%), but the difference was not statistically significant. The responder rate at 600 mg (17%) was also not significantly higher than in the placebo, but the responder rate in the 1,800 mg group (26%) was statistically significantly superior to the placebo rate. Response ratio was better in the gabapentin 1,200 mg/day group (-0.103) than in the placebo group (-0.022); but this difference was also not statistically significant (p = 0.224). A better response was seen in the gabapentin 600 mg/day group (-0.105) and 1,800 mg/day group (-0.222) than in the 1,200 mg/day group, with the 1,800 mg/day group achieving statistical significance compared to the placebo group.

A third study compared gabapentin 900 mg/day, in three divided doses (N=111), and placebo (N=109). An additional gabapentin 1,200 mg/day dosage group (N=52) provided dose-response data. A statistically significant difference in responder rate was seen in the gabapentin 900 mg/day group (22%) compared to that in the placebo group (10%). Response ratio was also statistically significantly superior in the gabapentin 900 mg/day group (-0.119) compared to that in the placebo group (-0.027), as was response ratio in 1,200 mg/day gabapentin (-0.184) compared to placebo.

Analyses were also performed in each study to examine the effect of gabapentin on preventing secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Patients who experienced a secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizure in either the baseline or in the treatment period in all three placebo-controlled studies were included in these analyses. There were several response ratio comparisons that showed a statistically significant advantage for gabapentin compared to placebo and favorable trends for almost all comparisons.

Analysis of responder rate using combined data from all three studies and all doses (N=162, gabapentin; N=89, placebo) also showed a significant advantage for gabapentin over placebo in reducing the frequency of secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

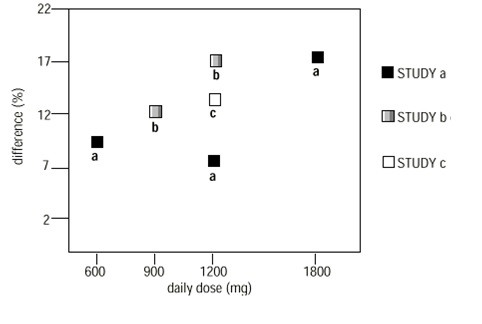

In two of the three controlled studies, more than one dose of gabapentin was used. Within each study, the results did not show a consistently increased response to dose. However, looking across studies, a trend toward increasing efficacy with increasing dose is evident (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Responder Rate in Patients Receiving gabapentin Expressed as a Difference from Placebo by Dose and Study: Adjunctive Therapy Studies in Patients ≥12 Years of Age with Partial Seizures

In the figure, treatment effect magnitude, measured on the Y axis in terms of the difference in the proportion of gabapentin and placebo-assigned patients attaining a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency from baseline, is plotted against the daily dose of gabapentin administered (X axis).

Although no formal analysis by gender has been performed, estimates of response (Response Ratio) derived from clinical trials (398 men, 307 women) indicate no important gender differences exist. There was no consistent pattern indicating that age had any effect on the response to gabapentin. There were insufficient numbers of patients of races other than Caucasian to permit a comparison of efficacy among racial groups.

A fourth study in pediatric patients age 3 to 12 years compared 25 to 35 mg/kg/day gabapentin (N=118) with placebo (N=127). For all partial seizures in the intent-to-treat population, the response ratio was statistically significantly better for the gabapentin group (-0.146) than for the placebo group (-0.079). For the same population, the responder rate for gabapentin (21%) was not significantly different from placebo (18%).

A study in pediatric patients age 1 month to 3 years compared 40 mg/kg/day gabapentin (N=38) with placebo (N=38) in patients who were receiving at least one marketed antiepileptic drug and had at least one partial seizure during the screening period (within 2 weeks prior to baseline). Patients had up to 48 hours of baseline and up to 72 hours of double-blind video EEG monitoring to record and count the occurrence of seizures. There were no statistically significant differences between treatments in either the response ratio or responder rate.

-

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

Product: 50436-0383

NDC: 50436-0383-4 24 CAPSULE in a BOTTLE

NDC: 50436-0383-9 9 CAPSULE in a BOTTLE

Product: 50436-0384

NDC: 50436-0384-4 24 CAPSULE in a BOTTLE

NDC: 50436-0384-9 9 CAPSULE in a BOTTLE

-

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Advise the patient to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Medication Guide).

Administration Information

Inform patients that gabapentin is taken orally with or without food. Inform patients that, should they divide the scored 600 mg or 800 mg tablet in order to administer a half-tablet, they should take the unused half-tablet as the next dose. Advise patients to discard half-tablets not used within 28 days of dividing the scored tablet.

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)/Multiorgan Hypersensitivity

Prior to initiation of treatment with gabapentin, instruct patients that a rash or other signs or symptoms of hypersensitivity (such as fever or lymphadenopathy) may herald a serious medical event and that the patient should report any such occurrence to a physician immediately [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Anaphylaxis and Angioedema

Advise patients to discontinue gabapentin and seek medical care if they develop signs or symptoms of anaphylaxis or angioedema [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].Dizziness and Somnolence and Effects on Driving and Operating Heavy Machinery

Advise patients that gabapentin may cause dizziness, somnolence, and other symptoms and signs of CNS depression. Other drugs with sedative properties may increase these symptoms. Accordingly, although patients’ ability to determine their level of impairment can be unreliable, advise them neither to drive a car nor to operate other complex machinery until they have gained sufficient experience on gabapentin to gauge whether or not it affects their mental and/or motor performance adversely. Inform patients that it is not known how long this effect lasts [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3) and Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Suicidal Thinking and Behavior

Counsel the patient, their caregivers, and families that AEDs, including gabapentin, may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Advise patients of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of symptoms of depression, any unusual changes in mood or behavior, or the emergence of suicidal thoughts, behavior, or thoughts about self-harm. Instruct patients to report behaviors of concern immediately to healthcare providers [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Use in Pregnancy

Instruct patients to notify their physician if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy, and to notify their physician if they are breast feeding or intend to breast feed during therapy [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1) and (8.2)].

Encourage patients to enroll in the NAAED Pregnancy Registry if they become pregnant. This registry is collecting information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. To enroll, patients can call the toll free number 1-888-233-2334 [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

-

MEDICATION GUIDEGabapentin Capsules, USPGabapentin Tablets, USP(gab'' a pen' tin)

What is the most important information I should know about gabapentin?

Do not stop taking gabapentin without first talking to your healthcare provider.

Stopping gabapentin suddenly can cause serious problems.

Gabapentin can cause serious side effects including:

1. Suicidal Thoughts. Like other antiepileptic drugs, gabapentin may cause suicidal thoughts or actions in a very small number of people, about 1 in 500.

Call a healthcare provider right away if you have any of these symptoms, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you:

- thoughts about suicide or dying

- attempts to commit suicide

- new or worse depression

- new or worse anxiety

- feeling agitated or restless

- panic attacks

- trouble sleeping (insomnia)

- new or worse irritability

- acting aggressive, being angry, or violent

- acting on dangerous impulses

- an extreme increase in activity and talking (mania)

- other unusual changes in behavior or mood

How can I watch for early symptoms of suicidal thoughts and actions?

- Pay attention to any changes, especially sudden changes, in mood, behaviors, thoughts, or feelings.

- Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider as scheduled.

Call your healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you are worried about symptoms.

Do not stop taking gabapentin without first talking to a healthcare provider.

- Stopping gabapentin suddenly can cause serious problems. Stopping a seizure medicine suddenly in a patient who has epilepsy can cause seizures that will not stop (status epilepticus).

- Suicidal thoughts or actions can be caused by things other than medicines. If you have suicidal thoughts or actions, your healthcare provider may check for other causes.

2. Changes in behavior and thinking - Using gabapentin in children 3 to 12 years of age can cause emotional changes, aggressive behavior, problems with concentration, restlessness, changes in school performance, and hyperactivity.

3. Gabapentin may cause serious or life-threatening allergic reactions that may affect your skin or other parts of your body such as your liver or blood cells. This may cause you to be hospitalized or to stop gabapentin. You may or may not have a rash with an allergic reaction caused by gabapentin. Call a healthcare provider right away if you have any of the following symptoms:

- skin rash

- hives

- difficulty breathing

- fever

- swollen glands that do not go away

- swelling of your face, lips, throat or tongue

- yellowing of your skin or of the whites of the eyes

- unusual bruising or bleeding

- severe fatigue or weakness

- unexpected muscle pain

- frequent infections

These symptoms may be the first signs of a serious reaction. A healthcare provider should examine you to decide if you should continue taking gabapentin.What is gabapentin?

Gabapentin is a prescription medicine used to treat:

- Pain from damaged nerves (postherpetic pain) that follows healing of shingles (a painful rash that comes after a herpes zoster infection) in adults.

- Partial seizures when taken together with other medicines in adults and children 3 years of age and older with seizures.

Who should not take gabapentin?

Do not take gabapentin if you are allergic to gabapentin or any of the other ingredients in gabapentin. See the end of this Medication Guide for a complete list of ingredients in gabapentin.

What should I tell my healthcare provider before taking gabapentin?

Before taking gabapentin, tell your healthcare provider if you:

- have or have had kidney problems or are on hemodialysis

- have or have had depression, mood problems, or suicidal thoughts or behavior

- have diabetes

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. It is not known if gabapentin can harm your unborn baby. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you become pregnant while taking gabapentin. You and your healthcare provider will decide if you should take gabapentin while you are pregnant.

- Pregnancy registry:If you become pregnant while taking gabapentin, talk to your healthcare provider about registering with the North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry. The purpose of this registry is to collect information about the safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. You can enroll in this registry by calling 1-888-233-2334.

- are breast-feeding or plan to breast-feed. Gabapentin can pass into breast milk. You and your healthcare provider should decide how you will feed your baby while you take gabapentin.

Tell your healthcare provider about all the medicines you take, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements.

Taking gabapentin with certain other medicines can cause side effects or affect how well they work. Do not start or stop other medicines without talking to your healthcare provider.

Know the medicines you take. Keep a list of them and show it to your healthcare provider and pharmacist when you get a new medicine.

How should I take gabapentin?

- Take gabapentin exactly as prescribed. Your healthcare provider will tell you how much gabapentin to take.

- Do not change your dose of gabapentin without talking to your healthcare provider.

- If you take gabapentin tablets and break a tablet in half, the unused half of the tablet should be taken at your next scheduled dose. Half tablets not used within 28 days of breaking should be thrown away.

- Take gabapentin capsules with water.

- Gabapentin tablets can be taken with or without food. If you take an antacid containing aluminum and magnesium, such as Maalox®, Mylanta®, Gelusil®, Gaviscon®, or Di- Gel®, you should wait at least 2 hours before taking your next dose of gabapentin.

If you take too much gabapentin, call your healthcare provider or your local Poison Control Center right away at 1-800-222-1222.

What should I avoid while taking gabapentin?

- Do not drink alcohol or take other medicines that make you sleepy or dizzy while taking gabapentin without first talking with your healthcare provider. Taking gabapentin with alcohol or drugs that cause sleepiness or dizziness may make your sleepiness or dizziness worse.

- Do not drive, operate heavy machinery, or do other dangerous activities until you know how gabapentin affects you. Gabapentin can slow your thinking and motor skills.

What are the possible side effects of gabapentin?

Gabapentin may cause serious side effects including:

See “What is the most important information I should know about gabapentin?”

- problems driving while using gabapentin. See “What I should avoid while taking gabapentin?”

- sleepiness and dizziness, which could increase the occurrence of accidental injury, including falls

- The most common side effects of gabapentin include:

- lack of coordination

- feeling tired

- viral infection

- fever

- feeling drowsy

- jerky movements

- nausea and vomiting

- difficulty with coordination

- difficulty with speaking

- double vision

- tremor

- unusual eye movement

- swelling, usually of legs and feet

Tell your healthcare provider if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away.

These are not all the possible side effects of gabapentin. For more information, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

How should I store gabapentin?

Store gabapentin capsules and tablets between 68°F to 77°F (20°C to 25°C).

Keep gabapentin and all medicines out of the reach of children.

General information about the safe and effective use of gabapentin

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use gabapentin for a condition for which it was not prescribed. Do not give gabapentin to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them.

This Medication Guide summarizes the most important information about gabapentin. If you would like more information, talk with your healthcare provider. You can ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist for information about gabapentin that was written for healthcare professionals.

For more information call ScieGen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. at 1-855-724-3436.

What are the ingredients in gabapentin capsules, USP and tablets, USP?

Active ingredient: gabapentin, USP

Inactive ingredients in the capsules: Pregelatinized starch (maize) and talc.

The 100-mg capsule shell also contains: gelatin, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), titanium dioxide.

The 300-mg capsule shell also contains: gelatin, titanium dioxide, FD&C Red 40, D&C Yellow 10, and sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS).

The 400-mg capsule shell also contains: gelatin, titanium dioxide, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), D&C Yellow 10, and FD&C Red 40.

The imprinting ink contains shellac, dehydrated alcohol, isopropyl alcohol, butyl alcohol, propylene glycol, strong ammonia solution, black iron oxide, and potassium hydroxide.

Inactive ingredients in the tablets: poloxamer 407, mannitol, magnesium stearate, hydroxypropyl cellulose, talc, copovidone, crospovidone, colloidal silicon dioxide and opadry white (03F180003).

Opadry white (03F180003) contains hypromellose, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol and talc.

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

All brands listed are the trademarks of their respective owners.

- SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

- Lidocaine Patch 5%

-

DESCRIPTION